Inside Egyptian artist Okasha’s home and gallery – a creative breeding ground he calls The Inflatable Space.

By Rahim Attarzadeh

Photographs by Dexter Navy

Inside Egyptian artist Okasha’s home and gallery – a creative breeding ground he calls The Inflatable Space.

Swerving into Egyptian artist Okasha’s home in London’s Little Venice neighbourhood is like entering an alternative universe. Anarchic, paradoxical, and sensorial, one is immediately struck by a heap of soil and palm trees, all belonging to the artwork he calls Love. Combining nature with a painted canvas, Love is adorned by his signature green brush strokes and one that truly conveys Okasha’s world and raw approach.

Okasha’s home is also his gallery-slash-exhibition-space. A chaotic, yet arresting mews house he calls The Inflatable Space which he has been living in for the past nine years has become the manifestation of his labyrinthine mind. After being rejected from Central Saint Martins to study fashion and textiles because he was not granted financial aid as a foreign student, Okasha worked as a stylist at Louis Vuitton for five years, sartorially refining the likes of rapper Drake and grime artist Dave. Fashion was never his calling, though: ‘I never opted for pieces that say look at me,’ he tells System. ‘I prefer ones that say leave me alone.’

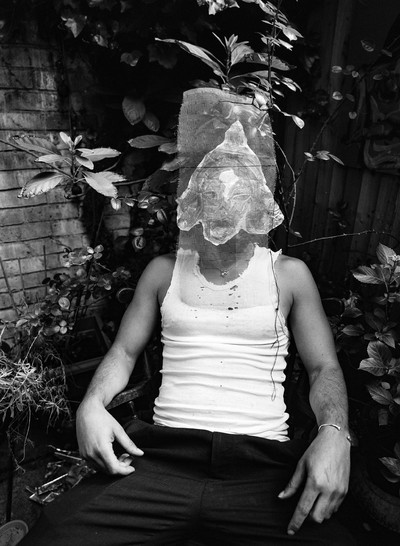

Sunflower Mesh, 2022.

Spanning his latest series of works, The Inflatable Space exhibition bears witness to his deconstructed techniques. Okasha’s artworks restitch painted and sculpted narratives from materials and canvases that are ‘imperfect’, or ‘broken.’ Using mesh to carve sculptural masks and painting on the ‘wrong side’ of a canvas, his work is a rhythmic homage to his roots growing up in the Cario suburb, Heliopolis. Making his inflatable bed in his gallery every morning and evening whilst rejecting the conventional norm of a bedroom is a reflection of his dictum: ‘A true artist must strive to become a natural alchemist.’

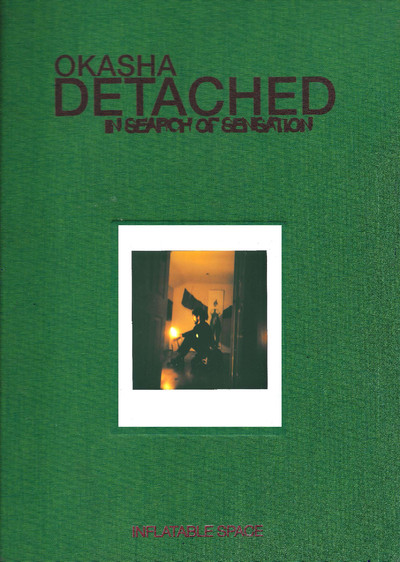

Detached: In Search Of Sensation is the title of Okasha’s first book – created partly in collaboration with filmmaker, photographer, visual documenter, and fellow Egyptian Dexter Navy. ‘I would not be the same photographer I am today if it wasn’t for my friendship with Okasha,” says Navy – whose work reads like a what’s what across the fields of fashion, film, music, and subculture: whether it be contributing to the pages of fashion magazines, directing A$AP Rocky’s LSD music video or shooting campaigns for the likes of Converse, Dior, Stussy, and Nike. ‘Okasha’s vision for his art is a true and total reflection of the life he is living. He assembles his inflatable bed every night and every morning. I was absorbed by his ephemeral living and all immersive space. We feel Egyptian in our ability to create from anything. It is a talent of seeing life and turning it into expression.’

Okasha is similarly complimentary when it comes to Navy’s visual language and forging of a legacy for a new generation of contemporary Egyptian creatives. ‘I’ve told him that his artistic self reminds me of the river Nile. Dexter’s work is like a powerful stream that will swirl through each crevice and canal. From time to time, it will flood and nourish the land with all it needs to grow.’ Okasha sat down with System to discuss his exhibition’s aesthetic ‘mesh-up’, why he humbly rejects the term artist and the unique process of transformation he calls ‘from dust to gold.’

Let’s go back in time. Where were you brought up?

Okasha: In a neighbourhood called Heliopolis in Cairo, Egypt. I spent most of my time with my mom and sister as my dad was always travelling for work. My mom writes poetry and paints. She would always read us her poems in the evening and I would watch her paint all over the house.

So you were exposed to art through your mom? What were some of your first visual memories?

Okasha: I was always fascinated by the idea of holding a brush and dipping it in colour. When I became aware of texture and colour, my mom would allow me to finish parts of her paintings. Eventually we started to paint side by side with the same colour palette. She never told me what to paint specifically. She always instilled the notion that painting is a noble reflection of one’s inner self.

For a lot of creatives growing up in the Middle East, their sense of creativity was born out of rebellion, or the visceral desire to not conform to convention, but you were encouraged to be creative?

Okasha: Creativity was born out of necessity. I remember when I learned how to fix my motorbike by myself. I was 16 and I got myself a Yamaha 600cc with all the money I saved with my salary from playing football and selling customised pieces of clothing. My family were very against the idea of me riding a motorbike and explicitly told me they would never give me a cent to fix or repair the bike. So I would constantly go to the local garage where I finally convinced the mechanic to let me be his assistant. In return, I learned how to fix and service my bike as it was very expensive to maintain.

‘A true artist must strive to become a natural alchemist. The ideal of transformation. I call the process: from dust to gold.’

When one considers Egyptian art, one immediately thinks of Ancient Egypt. However a contemporary culture boom was born in Cairo post the 2011 revolution out of chaos and despair. Cairo gifted the world new forms of street art in graffiti and musical genres such as Electro-Chaabi and Techno-Chaabi. Do you think Egyptian culture has progressed past a solely historical point of view?

Okasha: I’m stubbornly against the term ancient Egypt as I view it as a curse the modern world puts on us. I proudly consider myself an Egyptian when I look back on how my predecessors have erected the sublime symbols of Egypt. However I often find myself frustrated by the fact that the world does not always consider the prevalence of Egyptian culture without attributing the term ‘ancient’ next to it. Have you ever heard the term ancient being applied in Europe? We always acknowledge Western culture as contemporary but the same does not apply to the Middle East. There’s no Art Basel in Cairo… Art Cairo.

You often refer to Egyptian culture and your heritage as being part of the ‘sublime.’ Can you explain this?

Okasha: I believe Egypt has achieved what we call the sublime in all aspects of civilization. Our culture has endured death, destruction and multiple invasions. The sublime is the permanence Egyptian landmarks have withstood over such turbulence. To revert back to your previous question, I don’t believe we can progress past a historical point of view if creatives like myself and future generations don’t agree on the common goal in achieving the sublime again. We will only reach a cultural pinnacle if we truly define ourselves as Egyptian, not Ancient Egyptian.

You once told me that you never considered yourself to be an artist in your youth. Has that since changed?

Okasha: Not at all. I’m aware of the term ‘artist’, but I choose not to consider the sense of self-entitlement it can give you. I don’t have any motivation to call myself an artist because it is an impossible thing to define in its true sense. I think honest art, or just the ability to create is a journey into the unknown. A journey you will never navigate consciously. It’s more about the ability to experience new sensations over time.

Hence the title of your book, Detached: In Search of Sensation?

Okasha: The feeling of detachment is like seeing a painting through a window for the first time. At first glance, you see the beauty of painted colours on the surface, but over time you notice there are scratches on the very same window – it’s imperfect. If you start looking through those scratches and imperfections to see the light that shines through, you realise there is a new world that lies beyond the surface. That might sound far-fetched but for me my work has to be rooted in the same principle. My book explores the journey in finding the perfections in the imperfect and to see the light and colours that shine beyond the surface.

‘Have you ever heard the term ancient being applied in Europe? We always acknowledge Western culture as contemporary but the same does not apply to the Middle East.’

So would you say you interpret colour as a metaphor for identity and the journey one undertakes in garnering a sense of self-identity? Colour has a double meaning. What you immediately see on the outside does not reflect the intrinsic value of what you see on the inside?

Okasha: A true artist must strive to become a natural alchemist. The ideal of transformation. I call the process from dust to gold. That does not happen through our material love of gold, but gold as a true reflection of colour and the sun. Again, it reverts back to shining a light beyond the surface. Understanding and reinterpreting colour over time allows you to define your self-identity. Identity can only be nurtured and understood over time. I don’t believe in the allure of ephemerality.

You often speak about how hope and despair is emanated through your work. Your whole process is just a reflection of life! We do not live in a perfect world, particularly when it comes to the arts and creative industries. Would you say your work shows the absolute and imperative need to take risks and most importantly, to learn from our mistakes?

Okasha: My philosophy seeks to combat the trials and tribulations of everyday life but not in an attempt to subscribe to popular, or industry opinion. If I am fortunate enough for the industry to admire my work, then of course that is an additional benefit but by no means the mission statement. Trying to deal with how I feel everyday; waking up with great hope and only being able to sleep when I feel great despair is reflected on my canvases. I see sleep as this proverbial blessing and reward. We are able to reform ourselves and be reborn everyday like when the sun rises. Overtime, simultaneously acknowledging and accepting this pendulum of emotions has gifted me the belief to construct and create.

Deconstructionism is very present in your work. You tend to like things, or make things that are already broken, or imperfect. Where did the interest in seeking to recontextualise the unadorned and broken originate from?

Okasha: It all started from my fear of looking at a perfect blank canvas! I always work on the ‘wrong side’ of a canvas. The raw side I work from is impossible to erase. From that point, I experiment with different materials other than canvas. Any material I work with must come through my day-to-day life. The imperfection in materials that I use is simply to do with being human. We can’t be perfect but we strive to be. Fortunately, there’s no pseudo-intellectual explanation to my work. As you were saying earlier, we’re all human and we all make mistakes. Why can’t I aestheticise my mistakes?

Angel, 2020.

Inflatable Space gallery logo. Launched in November 2021.

Upon immediately entering your home and gallery, one can see that one of your works, entitled Love, are accompanied by soil and palm trees. Can you explain the reasoning behind the process?

Okasha: Love is a work catalysed by my intuition to create something that could live outside of its traditional canvas, whilst not being a sculpture per se. The work shows the necessity for things to be nurtured and kept alive, in this case by watering the palm trees regularly. It symbolises the relationship between nature and sensation. I’m interested in showing a visual harmony between the two but for my work to exist within the realm of reality. I want people to understand and relate to what I’m trying to illustrate without feeling like it’s nonsensical. Love is maintenance, fade away. That should be the title of my first album…

Well you have just started playing the guitar…

Okasha: To quote Jimi Hendrix: ‘Music is a safe kind of high.’

The sense of openness and improvisation within the materials you use to deconstruct and reconstruct your work appears to be a fundamental part of your practice. Is that something you have intentionally developed when assembling the Mesh Mask and the Sunflower Mesh pieces?

Okasha: Mesh is the aesthetic embodiment of my heritage and childhood in Egypt. Most of our windows were made from mesh. I developed these works lucidly. However the mesh is raw. When you are revealing something consciously, you are also revealing the organic, or raw process. The deconstruction of the mesh visually reconstructs the memories of my youth. That will always be a core feature within my work. Nothing I do is improvised!

‘Love is maintenance, fade away. That should be the title of my first album…’

You call your home and gallery The Inflatable Space. How did the name come about?

Okasha: The Inflatable Space name came from the underlying importance for my home to be my place of work. My home is a part of the exhibition itself. It’s ‘inflatable’ because it can be an exhibition space, or a bookstore, or a cinema, or all of the above in one. I like to think of it as an architectural triptych. I adapt the space by day and by night. I make my bed every night and disassemble it every morning. The essence of inflatable objects is the fastest way to transform a space. I’m not particularly interested in showing my work in a white wall gallery unless a curator would allow me to dismantle and domesticate the space. I’m not really into things that are ephemeral so whilst the space can be transformed, its location will remain permanent… as long as I can afford for it to remain permanent!

How did you find the space? You once told me that you specifically wanted to live in a mews house because Francis Bacon lived in one too.

Okasha: You are able to put one foot in your house and the other on the street at the same time. There’s something rewarding about feeling instantly free at any given moment. Do I sound pathetic in claiming it’s a homage to Francis Bacon just because he lived in a mews house in South Kensington? I don’t think it’s a bad thing to want to emulate other artists. Younger artists often appear so desperate to find a ‘uniqueness’ that they coincidentally end up being a pale imitation of their predecessors. It irks me. Of course young artists should always consider the likes of Francis Bacon. I consider the past to live in the present.

How important has your understanding of fashion been to your work and your ability to express yourself creatively and visually? When I first visited the Inflatable Space, I immediately noticed the Christopher Nemeth Louis Vuitton coat Kim Jones designed.

Okasha: I’ve always had a passion for fabrics and the way in which clothes move with the body. I am more interested in the idea of deconstructing fabric, similarly to what I’ve done with my art works. The way that the fabrics are cut are like brush strokes, or colour blocking. Imagine Rothko meets Issey Miyake. Clothing can be an art performance – just look at the Homme Plisse or Hussein Chalayan shows. A fashion designer does not necessarily have to collaborate with an artist to intersect the two. Miyake’s pleats bounce with the body – they are palpable. That’s as much art as it is fashion. It’s sartorial origami. The performances in the shows themselves are so deeply rooted in art. Everything people love about 80s fashion is predominantly a form of art. Silhouette is an artform. Look at how Dries assembles his patterns.

It becomes very obvious when one sees your space that the feeling of domesticity is so deeply interwoven in your DNA. We’ve spoken about the importance that The Inflatable Space has on your work, but what would you like it to reveal about yourself?

Okasha: Art should activate emotion and identity beyond just serving the viewer as an instant decoration. My home is my gallery. If you don’t come to my home, then you are unable to experience my artworks and what I want to communicate to the viewer through The Inflatable Space.

Fresco, 2018.

Excerpts taken from Okasha’s book entitled Detached In Search of Sensation.

Released in October 2021.

Detached foreword by Okasha

Photographs by Dexter Navy

Photography assistant: Dylan Massara