The personal archive of Katy England.

By Jerry Stafford

Photographs by Willy Vanderperre

Styling by Katy England

The personal archive of Katy England.

Katy England knows how to work a look. Stylist and creative consultant to Alexander McQueen from his earliest collections until a few years before his untimely death, England now collaborates closely with designer Riccardo Tisci, Creative Director of Givenchy, on both his women’s and men’s collections. She also continues to work as a freelance fashion editor and consultant to an intimate family of collaborators and friends.

England first met McQueen when she was the fashion editor of London’s Evening Standard newspaper in 1993, and he had just presented Taxi Driver, his first collection after graduating from Central Saint Martins. He saw something in the way she dressed, and asked her to come on board as his stylist, even though she had no previous experience of working with a designer. McQueen was right to follow what he intuitively saw in England – she became his ‘second opinion’ on every stage of the creative process: the research, the collections and spectacular shows.

System interviewed Katy England the same day London paid homage to McQueen at the opening of Savage Beauty – a retrospective of the designer’s work at the Victoria and Albert Museum – and the legendary Blitz Kid and Visage singer Steve Strange was mourned at a funeral service in his hometown of Porthcawl, Wales. In some way these two events seemed inextricably linked: celebrating the influential lives of two people whose creativity changed the way their generation considered ideas of gender, beauty and identity. Both McQueen and Strange were born of a particular London street culture: a sexual and social underground whose multi-layered substrata has constantly influenced the regeneration and reinvention of the city and its hybrid self-representation.

And it is exactly this enigmatic, intangible and indefinable quality which England has sourced and explored over the years in her work as a stylist and image-maker. She is constantly cross-referencing the posture and pose of rock iconography, and the sexual and social subversion of the street, reinterpreting fashion’s past through its present in order to create a spontaneous, emotional document.

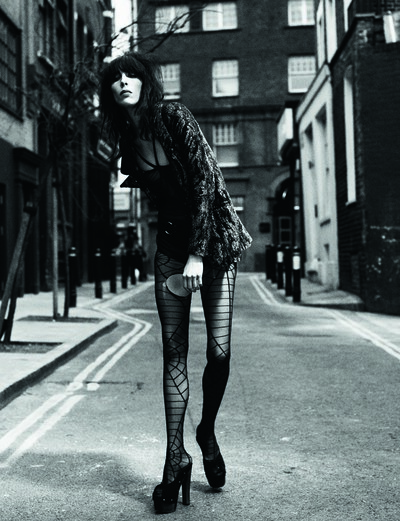

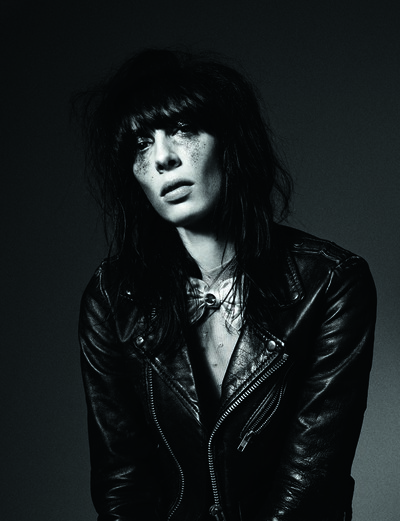

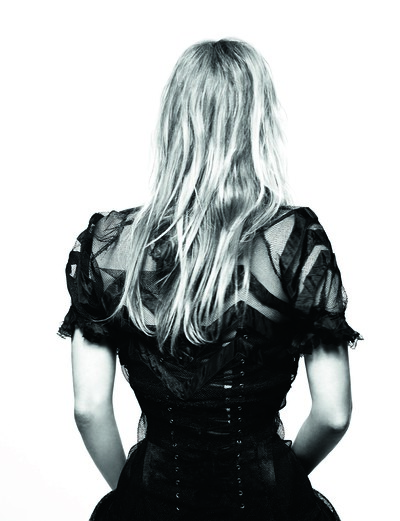

In the shoot for System, made in collaboration with photographer Willy Vanderperre, England drew upon her considerable personal archive and sourced clothes from across London’s best vintage collections in a response to the city’s convulsive urban beauty; to the music, attitude and energy which powers its cultural motor.

Jerry Stafford: Congratulations on the Givenchy show! It seemed so controlled and precisely executed – how did you feel about it?

Katy England: I think Riccardo [Tisci] is very mathematical, very logistical and he likes this tight control. He has proven methods of how he likes to approach his looks and his styling, and I’ve been working with him for about three years now, so I’ve learnt these and I’ve got used to his methods. Sometimes I find them a little too controlling and I sort of encourage him to break the rules a bit – because he sets himself the rules. And I sometimes question that and ask; why do we need to do that? It’s very clever and he is a very clever guy. I’ve spoken to people afterwards, to Bobby [Gillespie, England’s husband] and Alistair [Mackie, stylist] and friends who watched it, and they’ve said it was so well executed, and his is a formula that works. But perhaps because this was the first time I’ve worked with him on womenswear… it was interesting for me as I am more confident at womenswear.

It seemed more like a couture collection than prêt-a-porter …

Katy: I love the fact that he can give people both. We want ready-to-wear – I want ready-to-wear – and girls can really wear it, and it’s shown in a manner that’s cool, easy and wearable. I also think people want the beautiful workmanship and they also want the drama, and he manages both. I think it’s good to be like that. Why should they be separate?

So this is the first Givenchy women’s collection you’ve worked on? How does it differ from working on the men’s, aside from the fact you are clearly working on a different silhouette?

Katy: Givenchy has two completely different production methods, so it’s quite complicated. For the menswear, we have a lot more clothes that we style at a later point, whereas the womenswear is designed as outfits from the beginning, so there’s a totally different approach to each one. I think Riccardo enjoys the menswear, he has so much fun with it, and it’s very true to him – I feel like there’s a fun and enjoyment with that. But for me, it’s a little bit harder because I am not a man wearing it, and I think that’s the advantage of a woman coming to help a male designer with womenswear, in that we can wear it and say how we feel about wearing it – we have that opinion, and I think that’s why we are all doing these jobs!

‘The first shoot I ever did was glam rock, because it was my base level. I grew up in the Seventies and that stuff was all over the bloody telly.’

What is it that draws you to a designer like Tisci? Where do you think his strengths as a designer lie, and what is it about his character as well as his creative acumen that really appeals to you?

Katy: I have an attraction to strong women – I think I’ve just about worked that out now. In all of my work the girl has been quite tough and powerful, and that was something I did at the beginning with Lee [McQueen]. That was my connection with him back then; we liked the same type of girl. And now I’m finding that’s the same kind of thing with Riccardo, and so we connect with that.

Do you have similar cultural references in art, music, and photography – or is it more about the woman?

Katy: His woman is the Latino woman, and that’s quite new for me because that’s not been my woman, but I love it. He always, throughout the whole process, wants it to be real and he wants this reality so he doesn’t like it to get too theatrical, and I think I like that too. I mean obviously I love the theatrics, but even when I approach an editorial I want it to be desirable to the viewer, I want there to be a thread of something they can take away so it’s not just fantasy. I love fantasy, but I feel like I am more drawn to this reality as well.

How did you first meet Riccardo?

Katy: Jefferson [Hack] asked him to do a Givenchy special for Dazed & Confused, and he said he would do it, but only with me. So I said, ‘Okay, let’s give it a go’. And we did a great shoot together with [photographer] Matthew Stone, and it was under quite tricky circumstances; it was just before the holidays when everyone disappears. We got on so well, we just clicked and we made some great pictures – and then right after that he just asked if I would do the menswear, and that was the beginning.

You’ve always been interested in a fashion aesthetic that is cross-pollinated with music, art, subcultures and the street – how does this work with Tisci, who can have a very refined couture aesthetic? Do you help to counterbalance this, or does he already have this more subversive aesthetic embedded within his vision?

Katy: I think he already has this subversive aesthetic. He is really aware of the street, you know, for example, the show we just did [Autumn/Winter 2015/16] was all about Latino gang girls. He is amazing at the research – it’s from everywhere…

Do you also bring your own research when working with him?

Katy: Yeah. With the men’s, I’m there from the very beginning; so we go through all the ideas and that’s the process I love. It’s just so much more satisfying to be involved from the beginning and not just come in five days before the show, but to have been there all of the way, and to have helped on the shoes and so on. He really wants that, he really welcomes it. It’s an important thing to have those people around him, and he takes opinions from all of the team. He surrounds himself with really young people as well, and I think he’s a very open guy. I think that adds to the strength of the brand.

It’s a very different world now working in Paris with Givenchy to when you started at the Evening Standard in the 1990s and worked on the early Alexander McQueen shows. What was the first McQueen show you worked on?

Katy: It was called The Birds and it was in 1994 – we had just met a few months earlier, quite randomly, and he asked if I would style the show. And I had never styled a show before, but we connected and boom – that was the beginning.

How did you function as a team? Where did you find that first common ground – what were those shared interests, where did you go, what did you do together, where did you hang out?

Katy: Oh wow. At that time he was so innocent and it was just creatively led; it was never this discussion of production or the worry of selling. It was amazing! It was a total dream world. What did we do? He loved London; it was all very London-based. And where did we go? Um… clubs, London gay clubs really – but we were always milling around bookshops and galleries. I would come in and he would start talking about the collection, and then he’d get bored – so easily bored – so it’d be like, let’s go shopping! He liked to look round all the designer stores and, you know, I remember him buying me things like a Comme skirt, and a pair of shoes from Vuitton. He’d buy me these amazing things because he wanted to see someone in them. We were both obsessed with Margiela, and we would love to go looking at the all the designer stuff. I think it was just being out there and absorbing stuff on the streets. And he would get so excited when you’d see a great girl walking down the street who looks fierce and has got a major look – we all like that.

‘It’s great when you have gay friends who buy you extravagant odd things. Lee [McQueen] bought a Comme skirt just to see how it would look on me.’

Totally. And in your case, music has always been a driving force in how you put clothes together. Was this rock aesthetic already there when you worked with McQueen, or did it develop later as a personal signature?

Katy: I think it is something you already have in you. I remember the first shoot I ever did: I was still at the Evening Standard but Rankin said, ‘Come and do a shoot with me at Dazed and Confused’. I really wanted to do that kind of magazine, and he gave me the opportunity. The first shoot I ever did was rock, because it was my base level, let’s call it, and it was all about leather. There was this amazing jacket which funnily enough has been copied – it’s a very famous jacket by the General Trading Company, a beautiful appliquéd metallic jacket with a bird’s head on the collar; very glam rock – Miu Miu once did a whole season on it, and Riccardo actually had it in his references too. And that was my first shoot. You can’t get away from it: I grew up in the bloody Seventies and glam rock was on the telly.

In a more general sense, what do you believe the role of the stylist is? What was your role at McQueen? Was it to interpret the work of the designer – to inspire him or her to create in a particular way?

Katy: I think we are helping them, essentially. I mean, being a woman is part of the equation: they like looking at the way you wear clothes. I think we just need to inspire them, to come up with suggestions, inspirations, ideas, to be someone to talk to, to bounce with – is one part of the job. But then another part of the job is helping them to edit their own stuff, and as you go through the process to help them edit because there is always too much, too many ideas – and then sort of refine it all. They’ve got to value and like your taste, otherwise what are we doing?

Going back to the earliest part of McQueen’s career – which was missing from the New York retrospective – and will be justly celebrated in Savage Beauty here in London: how involved were you when it came to informing the V&A’s curators around the early period of McQueen’s career?

Katy: I wasn’t involved in Savage Beauty the first time around, at all. It was very close to his death and it was quite strange in that respect; I don’t know, a lot of people just felt quite closed and didn’t really want to deal with things. So I think it was interpreted at the Met in a very romantic way; obviously the most exceptional pieces, romantic and beautifully crafted pieces were used, because they are so impressive, and that was perhaps the angle there. I know that Sam Gainsbury [of production company Gainsbury & Whiting] and the brand felt that as he’s back in London – his hometown – you can’t be here and not talk about what he did in London at the very beginning.

How did you work with Claire Wilcox, the curator of the V&A show, on this particular section of the show?

Katy: We had to look at what archives were available, because not many pieces had ever been produced, or had been given away to people to wear; to friends, to wear in nightclubs, to models to pay them. Everything disappeared, so it became like, ‘Okay, what we can get our hands on?’ I actually had quite a bit from that time, myself, but if they did try to exhibit looks from every London show it would be a bit of a jumble. So in the end it was decided: Highland Rape, The Birds, and The Hunger [collections], and unfortunately they’re only on ten mannequins. I wish there were more because there is so much more to tell, but with ten you can somehow make a bit of coherence.

It kind of reminds me of the show that Tilda Swinton did with Olivier Saillard in Paris, where she held Napoleon’s jacket and smelt it as if to say, ‘If only this jacket could talk…’

Katy: It’s been amazing actually in that respect. Each of the pieces has a story for us – they have huge memories. I did a shoot for AnOther with Nick Knight, and I called upon all those colleagues and friends from the early days to get the pieces back from them for the shoot, and it was just like going on that journey again. Before that I wasn’t ready to do it, but now I was ready to embrace it, to re-look at it, to remember it all and to I think it is something you already have in you. I remember the first shoot I ever did: I was still at the Evening Standard but Rankin said, ‘Come and do a shoot with me at Dazed and Confused’. I really wanted to do that kind of magazine, and he gave me the opportunity. The first shoot I ever did was rock, because it was my base level, let’s call it, and it was all about leather. There was this amazing jacket which funnily enough has been copied – it’s a very famous jacket by the General Trading Company, a beautiful appliquéd metallic jacket with a bird’s head on the collar; very glam rock – Miu Miu once did a whole season on it, and Riccardo actually had it in his references too. And that was my first shoot. You can’t get away from it: I grew up in the bloody Seventies and glam rock was on the telly.

In a more general sense, what do you believe the role of the stylist is? What was your role at McQueen? Was it to interpret the work of the designer – to inspire him or her to create in a particular way?

Katy: I think we are helping them, essentially. I mean, being a woman is part of the equation: they like looking at the way you wear clothes. I think we just need to inspire them, to come up with suggestions, inspirations, ideas, to be someone to talk to, to bounce with – is one part of the job. But then another part of the job is helping them to edit their own stuff, and as you go through the process to help them edit because there is always too much, too many ideas – and then sort of refine it all. They’ve got to value and like your taste, otherwise what are we doing?

Going back to the earliest part of McQueen’s career – which was missing from the New York retrospective – and will be justly celebrated in Savage Beauty here in London: how involved were you when it came to informing the V&A’s curators around the early period of McQueen’s career?

Katy: I wasn’t involved in Savage Beauty the first time around, at all. It was very close to his death and it was quite strange in that respect; I don’t know, a lot of people just felt quite closed and didn’t really want to deal with things. So I think it was interpreted at the Met in a very romantic way; obviously the most exceptional pieces, romantic and beautifully crafted pieces were used, because they are so impressive, and that was perhaps the angle there. I know that Sam Gainsbury [of production company Gainsbury & Whiting] and the brand felt that as he’s back in London – his hometown – you can’t be here and not talk about what he did in London at the very beginning.

How did you work with Claire Wilcox, the curator of the V&A show, on this particular section of the show?

Katy: We had to look at what archives were available, because not many pieces had ever been produced, or had been given away to people to wear; to friends, to wear in nightclubs, to models to pay them. Everything disappeared, so it became like, ‘Okay, what we can get our hands on?’ I actually had quite a bit from that time, myself, but if they did try to exhibit looks from every London show it would be a bit of a jumble. So in the end it was decided: Highland Rape, The Birds, and The Hunger [collections], and unfortunately they’re only on ten mannequins. I wish there were more because there is so much more to tell, but with ten you can somehow make a bit of coherence.

It kind of reminds me of the show that Tilda Swinton did with Olivier Saillard in Paris, where she held Napoleon’s jacket and smelt it as if to say, ‘If only this jacket could talk…’

Katy: It’s been amazing actually in that respect. Each of the pieces has a story for us – they have huge memories. I did a shoot for AnOther with Nick Knight, and I called upon all those colleagues and friends from the early days to get the pieces back from them for the shoot, and it was just like going on that journey again. Before that I wasn’t ready to do it, but now I was ready to embrace it, to re-look at it, to remember it all and to celebrate all the amazing times we had, and to try and enjoy and talk about it, because it’s so interesting.

‘Joan Jett is one of my all-time inspirations. Every time I see pictures of the Runaways, they have that attitude I love – they are just ballsy girls.’

Are there pieces of your own in the show itself?

Katy: Yeah, from The Birds. He made a lot of plastic stuff for The Birds, and it’s all really raw, like little t-shirts that were sewn together by himself made from this strange plastic. He always liked really odd materials because he couldn’t really afford Italian fabric companies, so he was in Berwick Street finding crap and dyeing, bleaching, and spraying it – that I think is really the London bit. What did I have? A skirt and trousers from The Birds show that are [made from]… we called it foil – but they’re white cotton ‘bumsters’, that he put through this foiling process, which is like a black layer of plastic that goes over them and it looks like a print. There’s that, and The Birds show was all about road kill, so we had the car tyre print.

Let’s have a look at the shoot you just did with Willy Vanderperre. Why did you choose a Belgian photographer, rather than someone more associated with London’s cultural soil?

Katy: Because Willy is hugely fashion, and so knowledgeable about fashion, he is inspiring to work with because he understands all these references. He has been around fashion for like 25 years. I don’t know his origins…

He was at the same college… as Raf [Simons]. What I like about working with him is that he understands styling so well, and I feel like I’ve got a bit of a partner.

Is this the first time you and Willy have worked together?

Katy: No, we did a couple of great stories for V magazine, which went well; and we love working together. I love the way he gets his head around the styling, he doesn’t just wait for you to present the look to him and be like, ‘Okay, now I’ll photograph it’. He is in the styling room and he’s enjoying it with you.

Looking at these pictures of Jamie Bochert, please can you give us a bit of the back story to them: what are the references, musical, cultural or street references that you are sourcing there?

Katy: I looked at my clothes, my higgledy-piggledy archive, and I thought about the New York Dolls because there’s so much of this glam rock in there, and I started thinking, ‘Well what have I got and how do I do it?’ I just felt that this shoot should be my thing; just trying to get to the essence of my old wardrobe I suppose. I love vintage and am always going round to my little sources in London, and you know, I bought that body suit about seven years ago and it had a beautiful little waistcoat that went with it which Kate Moss once wore on a cover of Esquire. And obviously it is tiny, and I could never wear it, but I wanted to put it in a frame I thought was so cute. Anyway, Jamie saw it and was like, ‘Wow’. She was so sweet – she was in the middle of the New York shows and she flew herself here for one day and had to leave the same day – and I am just impressed because she is just so tiny, and she fits the clothes I can’t fit into anymore [laughs].

For me I am also seeing a bit of Alice Cooper in there…

Katy: Oh yeah, that is Alice Cooper. The bow tie actually belongs to Johnny Thunders [from The New York Dolls] – we called her Johnny that day because of it. Bobby [Gillespie] has Johnny Thunders’ bow tie. He owns it.

Where is the top from?

Katy: It’s a little dress and it’s from Mr Freedom. It’s quite a famous little dress – Alistair Mackie bought it for me. It’s great when you have gay friends who want to buy you extravagant odd things.

Was this Mr Freedom dress made in 1973? If so, was it an explicit reference to the iconic Bowie stripe?

Katy: It’s got the Mr Freedom label from back in the day.

Now let’s come to someone who we are both very fond of… Why did you cast Kate Moss in this shoot?

Katy: Because of our history, and we have the same style in some respects; we have similar tastes. I tried to go on being true to myself, and she is part of it all.

You have a long-standing relationship with her, and have done many projects with her…

Katy: I also know we look good in the same clothes because of the length of our bodies. Her legs are longer and skinnier, but when she did all the fittings, I would fit into all her dresses before knowing that they would be for Kate.

‘I think stylists need to inspire designers. They’ve got to value your ideas and like your tastes. Otherwise, what are we doing?’

When did you guys first meet?

Katy: We probably got really pally when our kids were born and she started her relationship with Jefferson, which is now 13, 14 years ago. I was very close to Jefferson, I grew up with him in the magazine and he was very friendly with Kate, so she got more friendly with me, and then we both had children very close together – and you know that’s what happens when you have kids: you want to be with other people who also have kids.

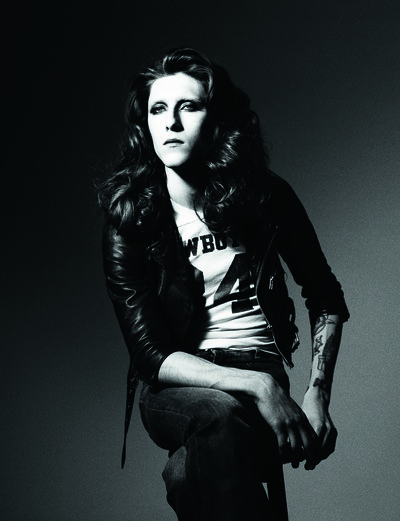

So let’s look at the pictures of Kate here, what are these pieces and why these pieces?

Katy: You know what, it was very spontaneous this shoot; I didn’t plan ahead. I just bought along tonnes and tonnes of stuff that I dug out of my wardrobe I was sort of playing with, and I just wanted it to be spontaneous because I miss that way of working… I bought this Junya Watanabe jacket because I love jackets, like most designers or stylists – that was one that Steven [Phillip] from Rellik showed me and it fitted perfectly. I think I bought that last year; the Victoriana jacket with a tulle coat over it, which you can’t see so well. It’s lovely, because I think there are two sides to me; I love pink fluffy dresses with roses and tulle. And so I have this collection of romantic, long, tulle-y type things. And this is one of them over the leather jacket – so that is the combination of my taste, let’s say with the rock t-shirt underneath.

I was going to come to the t-shirt, a signature aspect of your work – and I think there’s a Joan Jett one somewhere in the Givenchy collection.

Katy: Joan Jett is one of my all-time great inspirations because I guess it’s that tough girl thing. Why that is attractive to me, I just don’t know, but she is. The leathers, every time I see pictures of her, the Runaways – they are just ballsy girls and they don’t give a shit – they just have that attitude I love.

Tell me about the casting? Were you looking for a particular physiognomy?

Katy: Well, the New York Dolls thing: that’s why the guys got the make-up, and why I picked little Josh Quentin, the guy with red hair – he is so cute and inspiring, and I know him from around London. He looks like one of the New York Dolls, and he lives his life like that, so I thought I’ve got to have him. The other boy, Jake, is just quite beautiful and I love a classic man in make-up. I just feel like, boy or girl, it doesn’t really matter – It wasn’t defined as menswear or womenswear; it is all mixed up.

And just going back to this London thing – what is the obsession with London? Why not further north, places like Manchester, or Liverpool, where there have been other equally influential musical and cultural movements?

Katy: Well, I grew up in Manchester and was at Manchester Polytechnic studying fashion there for four years, but it was only in London when I clicked. I came here and thought, ‘Okay, this is it, this is my place’, and you meet like-minded people and you feel comfortable.

You were saying that you and Kate have very similar tastes in style – she has a long-standing love affair with rock as a style reference as well. Where do your tastes or aesthetics diverge, or are they really that close?

Katy: Kate is more classic, I would say, as she is in the public eye and so has to be so aware of what flatters her because she is going to have her bloody picture taken all the time. Whereas I love a more Japanese fit and aesthetic – I don’t think she likes that so much. The rock thing is connected, I guess the 1970s connection too; but she goes more feminine than I would. I think we feed off each other like that; we like bits of each other’s styles and then we put it together.

You both have musician boyfriends; what is it is that attracts you to that mode of expression?

Katy: I am attracted to people who wear their clothes really well, when you see that character and you think, ‘Oh my god, they look amazing’. They know their shape, they look confident… I think it’s the energy, and the don’t-give-a-shit confidence.

Just going back to street style, which has always existed on a social level and was a key fashion influence in the 1970s and ‘80s – and then it permeated fashion globally with the whole network of magazines. What was your first experience of street or club culture? Where did that first frisson of energy and excitement come from?

Katy: Apart from Top of the Pops, the very taste was in a small village called Betley near Crewe, where I was brought up – and we’d heard there was this nightclub called the Cheshire Cat on a Sunday, but it was for youngsters. I think I was 14. So me and my friend, who was also really into fashion, thought to go to this club, and we spent the whole afternoon getting ready. I was into Adam and the Ants, and she was into Toyah Wilcox; and she painted her face like Toyah, and I had tight trousers with a big blouse, and feathers and belts, and it was all a bit Spandau Ballet, Bowie, Adam. So off we went on the bus to this nightclub and we got there, and everyone was like, ‘Who are these people? Look at them’, and everyone started taking photographs of us. I walked into the club feeling really confident, and I thought, ‘Ooh, I love this, this is amazing’. And so that became our thing, it was our regular little haunt, but it wasn’t really that inspiring, we were almost the ones that were ‘out there’. I think when I went to Manchester Poly, I remember Michael Clark came and did Performing Clothes. He was touring and all these kids from London came up, and I met Alix Sharkey from i-D magazine, he was the editor at the time. And people looked incredible; it blew my mind.

‘Kate is more classic – she’s in the public eye so has to be aware of what flatters her. Whereas I love a Japanese fit. The rock thing is our connection.’

It’s funny you should say that because it’s Steve Strange’s funeral today, who was one of London’s club culture’s iconic figures, and he led that whole New Romantic movement which you are alluding to – and its leading players have been reappraised recently, particularly with another exhibition at the V&A last year. And of course some of the other cultural phenomena at that time, like Boy George, Michael Clark, artists and club personalities like Leigh Bowery, didn’t view fashion through prisms of gender. How have these kind of figures affected your own creative vision having experienced it personally, at this formative age?

Katy: Hugely. I remember the first time I saw Boy George, it was on Top of the Pops, and I thought, ‘Oh my god! I don’t know if it’s a man or a woman’. I really didn’t know – I don’t think it was something I was that bothered about – I just think it was really, really intriguing. And I mean, god, they are like icons really aren’t they? I mean, what can I say?

Has their cultural legacy become part of your DNA, and the way you approach styling?

Katy: Oh yeah, I did that Michael Clark story once in AnOther and that was one of my favourite stories I have ever done. But I have to say, I try to be natural with my approach – I don’t like references, but they are there, so I pull the natural ones that are in there and are mine – but I don’t really go off on a reference hunt. Maybe that’s it; I try to be spontaneous and true because I want it to be personal. Because if I don’t do me, then what’s the point? You know what I mean?

Moving on to the 1990s, how did they differ from the previous decade?

Katy: I know I was starting out trying to produce, trying to be creative in my own little way. I know we weren’t excited by the catwalks – it was as if Versace, Mugler, all those labels seemed too far away, and I don’t think I could have even laid my hands on those clothes anyway because I was really junior. I never started my approach to a fashion story with the catwalk. I started with what was around me. So I remember working with Phil Poynter and going to a New York hotel called Hotel 17, where all these club kids lived and hung out, and that kind of thing was the inspiration for my story. It wasn’t ‘Okay, let’s look at the runway and they’ve got x, y, and z’. Never. It was about living it, you were part of it – I was going to clubs, I was doing the door of the Dazed & Confused nightclub, so I’d see these great kids. I remember Keith Martin, the model, dyeing his hair leopard print, and putting people from the clubs in shoots because they were on your doorstep, and you didn’t have the facilities to be paying models anyway.

Do you think the YBA phenomenon that came to the fore in the 1990s had a big influence on you and the people you worked with then? People like Damien Hirst, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Sam Taylor-Wood…? This was something that hadn’t really happened before in London, and it kind of merged intrinsically with the fashion world.

Katy: I think we really felt it because it feels to me that Dazed & Confused, the artists and Lee McQueen, were all part of the same thing. I remember doing a Dazed interview with Lee, and Lee was making clothes for the Chapmans’ mannequins – it’s incredible, the guys with the cock faces and stuff. And there was one mannequin with all these conjoined bodies and Lee was making ‘bumsters’ for them, and we took the ‘bumsters’ – Jake has a film of this – Lee, Jake, Dinos, me, a load of dogs and Lee’s dog, went to a wasteland in the East End and filmed the dummy with the ‘bumsters’ on. And I feel that Lee was one of those artists. All this was going on, and we knew them and just saw them walking down the street; just down Old Street, because it was all happening in Old Street anyway – that was a new area that was coming up away from the city, and all the cool guys were living in warehouses and that was the thing to do. Dazed & Confused was there; it was all around.

‘I love a classic man in make-up. I just feel like, boy or girl, it doesn’t really matter; it’s all mushed up. I don’t feel like there are any boundaries.’

That was very ‘90s I think. Going back to something we were talking about: the past and how vintage plays a key role in your approach to styling. Does the term ‘vintage’ have any significance now that people refer to an outfit from 2010 as vintage? How do you work with vintage clothes?

Katy: I’m just so excited by the techniques. [When you look at] clothes that are over 100 years old, it’s the technical side which I think, ‘Oh my god, look at the embroidery, look at the shape of the sleeve, look at the buttons’ – you appreciate it in a very detailed kind of way.

It comes back to the rock t-shirt we touched on earlier, because they are sort of a vintage staple in your aesthetic. Why? Are they like postage stamps, little cultural signifiers, little ways into a particular time or place?

Katy: I think since living with Bobby – 15 years or whatever it is – his are very much that; they are memories, like his record collection. And he is a music collector, so that has infiltrated into me through my relationship with him. But the one in the shoot, the Guns N’ Roses t-shirt – and this is a point where we differ – is that I really do like AC/DC, Guns N’ Roses, Aerosmith.

Without irony?

Katy: Yeah, I love them. I’ve seen AC/DC three times – it’s my favourite gig! I’m a real fan; it’s the basic core-level rock. When I was at school, on the bus, it was Led-Zep, so it’s not pretend. I love it.

Do you see yourself – sorry to use this rather bombastic term – as an iconoclast in terms of the vision you strive to create? Where do you want to take the spectator when you are making fashion images? Is it to question our perception of others, the body, our appearance?

Katy: Oh god… I just want to be open. I want to think that anything is possible, you know, voluptuous big girls can look fantastic. Boys wearing women’s clothes, girls wearing men’s clothes, people that don’t have the perfect bodies: I just think that we can do anything, and I don’t feel like there are any boundaries. The most difficult shoot I did was the McQueen issue of Dazed, the disabled – ‘Fashion-able’ – issue, with Aimee Mullins. But when we came out of it, one of the girls who was modelling said, ‘Oh, I never thought I would look so beautiful’. That was it.

How do you feel when you walk through the Savage Beauty show? How do you feel about McQueen being elevated to historical importance in a museum like the V&A?

Katy: Kind of mixed because you feel so sad that he is not still here, because if he was we wouldn’t be at the V&A – he would probably have done an exhibition, but it would be completely different. So I just feel sadness that he is not here anymore with us. But [also] immensely proud, like, wow this guy achieved all this; and when you see it together it is quite unbelievable. I feel sad I think, yeah…

How have you changed as an artist and collaborator in recent years – what is it that’s important for you to express in your work now?

Katy: Well the industry has hugely changed, so when we set out twenty years it was purely about creativity – like my beginnings with Lee, my beginnings at these new magazines – we weren’t interested in advertising sales or anything, it was purely, purely creative. Now the business has changed and the digital age has changed it. I took a bit of a break and came back, and was like, ‘Whoa, what is going on?’ It is so different, so business-y and really, I just want to keep trying to hold onto my original creativity. I can’t be a fashion editor at a magazine [anymore], because there are all those obligations, and I’m not that kind of girl. If people want me to do a shoot for a magazine like System or AnOther and they want a little bit of something that I can bring, something that is quite personal and not constrained by the advertisers and isn’t the catwalk looks that magazines have to do, then I am really happy to do it.