How a Polish graphic design master took a French shoe brand into his wonderland.

By Thomas Lenthal

How a Polish graphic design master took a French shoe brand into his wonderland.

Born in 1930 in Lwòw, after studying at the then Polish city’s School of Artistic Industry, Roman Cieslewicz moved to Krakòw at the tail end of the 1940s to enrol at its Academy of Fine Arts. There, under the tutelage of George Karolak, a graphic artist who shunned the state sanction aesthetic of socialist realism, Cieslewicz was encouraged to create completely new modes of expression unencumbered by the aesthetic mores of the Iron Curtain. Inspired by the Blok Group, a revolutionary association of poets, typographers and montagists, and avant-garde artists such as Mieczyslaw Berman, Tadeusz Kantor and Ludwik Gardowski – at a time he has likened to living in a “cultural desert” – Cieslewicz developed a visual language that employed the collage techniques of Alexander Rodchenko and John Heartfield to personal fixations of circles, hands, eyes, legs and lips. It was a graphic style that imbued elements of the Soviet constructivists with the free associations of the Surrealists, one open to accidents and semiotic happenstance.

Having worked at a Polish propaganda agency and art directed Ti y Ja, a fashion magazine which he formatted along the lines of its Western equivalents like Elle – in 1963 Cieslewicz moved to Europe, eager to see how his work would stand up against its “neon lights.” Working from a studio in suburban Paris, he began refining his aesthetic, with its uncanny compositional imbalances and dialogue between the hand-made and the mechanical. He soon caught the attention of Peter Knapp, the then art director of Elle, who initially commissioned him to design photomontages to illustrate their features.

Such was his acute eye for typography, photography and the nuances of composition, Cieslewicz went on to succeed Knapp as Elle’s art director in 1965 – a key moment in a career that saw the Polish affichiste [poster-artist] also design catalogues and posters for the Pompidou Center in the same decade. Having become a naturalised French citizen in 1971, Cieslewicz began teaching at the city’s Ecole Superieure d’Arts Graphiques Penninghen a couple of years later, where he left an indelible impression upon his alumni – to the extent that one of them commissioned his master to create the advertising campaigns for Charles Jourdan in one of his early jobs after graduating.

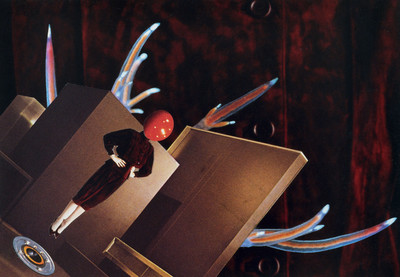

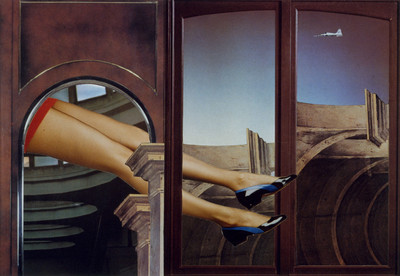

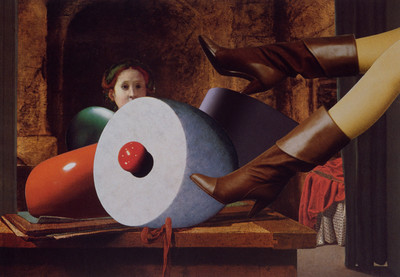

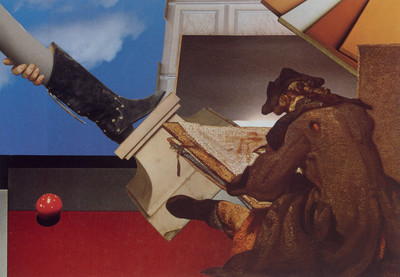

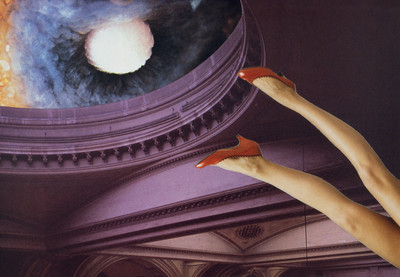

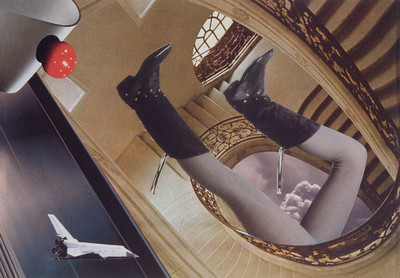

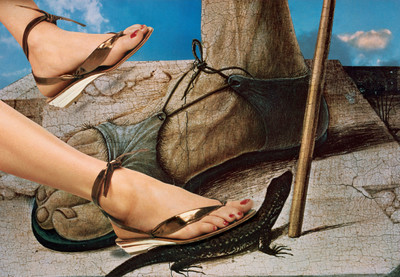

As the first shoe designer to advertise in fashion magazines back in the 1930s, Charles Jourdan more than recognised the importance of imagery to marketing their signature stilettos – over the course of 15 years, the brand’s collaborations with Guy Bourdin led to some of the most iconic fashion photography ever made. As such, to immediately follow in Bourdin’s footsteps could have been an especially intimidating brief. Yet Cieslewicz proved to be an inspired choice, as the Polish artist’s appropriation of paintings by the Old Masters, and playful use of composition and scale, resulted in some of the most uniquely arresting – and certainly leftfield – imagery to ever be commissioned by a fashion brand.

Cieslewicz worked his magic from a small atelier in Malakoff, a suburb south of Paris, and passed away in 1996 following a career that was as prolific as it was diverse; one which garnered a huge number of awards, and inspired countless others. Here his widow, Chantal Petit-Cieslewicz, is joined by Frank Salier – the Penninghen student who commissioned Cieslewicz to create the Charles Jourdan campaigns – and System’s Thomas Lenthal, a fellow Penninghen graduate, to discuss the dynamic between Cieslewicz’s avant-garde aesthetic and the constrains of commerce.

Thomas Lenthal: Frank, before we discuss your work with Roman for Charles Jourdan, I have some questions about what the brand meant at that time to put everything into context. Something that is extraordinary in the history of Jourdan was their collaboration with Guy Bourdin. How did you begin working with Jourdan? You were one of Roman’s students, right?

Frank Salier: Yes, I was one of Roman’s pupils. I graduated from Penninghen, top of my class; I can’t remember what year. I got very good marks with Roman. But I was into typography – I’d chosen Paul Gabor1 to be my thesis lecturer, and Roman was already very much in demand by so many others. Then I started at M.A.F.I.A.

‘We needed something suitably crazy to break away from Guy Bourdin’s work. So pretty quickly we thought, ‘Well, what about Roman?’’

Did they still have [the supermarket chain] Prisunic as a client then at M.A.F.I.A.?

No, they had Yves Saint Laurent and Absorba; they were the big ones at the time. They also had Les 3 Suisses3. At that time – this was the funny thing at M.A.F.I.A. – to test a new photographer they would give them Les 3 Suisses press pack, which was systematically photographed against a white background in black and white. So, the first time I worked with Paolo Roversi, who had just arrived from Italy, he too had to do the press pack for Les 3 Suisses! It was funny – everyone had to start like that. It’s a good learning process; I stayed there for three and a half years and then I wanted a change. I looked for work and lots of different contracts with various agencies. I chose the one that did the most different things.

And what was it called?

Ketchum. And when I arrived, the guy had started prospecting like crazy and he was only looking for fashion contracts. And we got Charles Jourdan…

And at the time were you interested in Charles Jourdan?

Yes, of course, because of Guy Bourdin.

Was it a luxury brand or a mainstream brand then? Expensive or cheap?

It had always been a pretty luxurious brand. Charles Jourdan’s speciality had always been the heel – that was their strength and their trademark. The Jourdan heeled pump was a classic – it was the Louboutin of its day. Of course, that was before the ‘80s, when things started changing and they lost their direction… they did a design for a shoe that was more mainstream and it totally ruined the brand. They launched a ready-to-wear line which was in a way nonsense; it wasn’t their craft.

Did you have to pitch to get Jourdan? Whose client were they?

No I don’t think so; the guy came and asked the agency boss if he could do it. We knew we had to do something really good in the wake of Bourdin’s work. What could we do to break from Bourdin’s imagery? I’d met him at M.A.F.I.A. in 1980, but I didn’t know why Bourdin was no longer doing Jourdan… It was strange.

So you ended up questioning yourself, saying, ‘Okay, how am I going to follow Bourdin?’

Exactly. We needed something suitably crazy to break away from Bourdin, whose work was marvellous of course – but something photographic wasn’t really an option. So pretty quickly we thought, well, ‘What about Roman?’ Because he did images, they were pictorial but with a craziness that was ultra-interesting and coupled with such modernity. So I called him and asked if he wanted to do the Jourdan campaign, and he said yes straight away, and I think he was very happy to do it. He proposed two images – the Indian and the Michelangelo – which we showed as mock-ups to Jourdan.

And they understood the work straight away?

Yes. With Roman we’d decided to keep the space for the shoe inside the image in relation to the Bourdin campaign. It’s very interesting keeping the scale of the shoe – and it’s quite modest in the world of advertising. We wanted to maintain that relationship; so the shoe would be a detail within.

So just to elaborate here, Roman went off and did his own thing – were you in contact with him then to develop the concept?

No, I simply told him I thought it should be done with old works of art.

And why did you think that?

It was ideal for collage, but also I liked the discrepancy. I had to photograph all the legs and everything here. So I did the photos with a leg photographer and then I gave them to him. We did different leg movements so he had enough materials to play around with in the collages. We decided to start mainly with Old Masters, to go with the Renaissance, with Michelangelo etc… and then later we did something more modern – that was for a second campaign. We did two seasons together.

Why did it end?

Because they didn’t want to get stuck with just one artist, they wanted to keep evolving. I did other things afterwards. I did something with a Belgian guy who did things with Polaroids, collages, which was kind of at the same time as when Hockney was doing his Polaroids.

The two campaigns generated a large variety of images though. When Roman presented his first season to Jourdan, were they happy?

Yes, it was very successful. We won lots of awards. It was wonderful.

‘We decided to keep the space for the shoe inside the image, so the shoe would be a detail within. It was quite modest in the world of advertising.’

I think it’s one of the most beautiful ad campaigns of its time. Did Roman meet with Jourdan?

No not all, it was me who took the mock-ups to them. I went to Malakoff [a suburb south of Paris] to see Roman.

Did he have carte blanche?

Yes of course.

So for two seasons you saw Roman, but only for the project?

Yes, only for that. I was quite intimidated to be in front of my former teacher. I was young. I was just starting out then – I was 27 years old. I’d spent three years at M.A.F.I.A. where I’d been more of an assistant. He was very kind but he was still my teacher and I was very respectful of him and his work.

This is a question for both of you, Frank and Chantal. We know that Roman had worked at Elle with Peter Knapp – what was his relationship with fashion and photography of that nature? Because 80 percent of his work is more cultural than commercial…

Chantal Petit-Cieslewicz: For him it was the same. He could do both at once without any problem. He worked for quite a long time at Elle – he was artistic director at one point – and then at M.A.F.I.A. he did work for Galeries Lafayette. He also worked for Vogue. At Elle he worked with Peter Knapp for a while, and at Vogue with Antoine Kieffer, the artistic director. But it was at Elle he really made a mark.

So he liked fashion then?

CPC: He didn’t make any particular hierarchical distinction in the things he did. He started in that domain when he arrived in Paris, and even back in Poland where he’d worked on a magazine that was called Ty i Ja [You and Me]. He really liked that.

Did you have to present Roman’s work before you started work on the Jourdan campaign?

FS: Yes, of course. He’d done lots of things, but we still had to present his work – that’s normal though. I mean he wasn’t super well known in that milieu.

CPC: He was starting to become well known. It was a time that was very prolific for him. I remember at the time he didn’t stop, his posters, catalogues, books, expositions of his own work and so on…

Did Roman know who Charles Jourdan was?

FS: Yes. It was a big brand and a good one. And he knew Bourdin’s work.

TL: Did he admire it?

CPC: Yes. I’m pretty sure that he worked with Bourdin at Elle or Vogue too.

Were the Jourdan images used outside of women’s magazines, on posters?

FS: No. They were in all the fashion magazines though.

So, Chantal, how did he amass his iconography, these cutout images?

CPC: He had incredible archives. He had files with themes and he had entire walls for these archives.

Did they come from magazines, books…?

CPC: Everywhere, there were piles of magazines everywhere – his studio was invaded by magazines. He cut things out and then there was no question of throwing anything away. He just amassed everything; I could never throw anything away.

Was he methodical in his organisation of everything?

CPC: Oh yes, very much so. He was like a computer. I gave his archives to the IMEC [Institut Mémoire de l’édition Contemporaine] where everything is visible. There’s going to be a big exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décorifs in Paris, in 2016 using his archives. They are truly incredible – I also donated some of it to the modern art museum in Grenoble.

‘Sometimes he would sign his work if it appeared in the press. For him that was the oeuvre. He was more interested in the work that was shared.’

Do you know, for example with a subject like this, how he would work on it? Was he instantly inspired?

FS: I think he did the project quickly. Roman was into photomontages because they were part of his personal work too, so then he re-used the idea for Jourdan. It came from a similar series that he was doing at the time…

The images are so complex – they draw us into a rarefied culture that few people refer to. At the time you get the impression that it would have been done without asking too many questions.

FS: Well it was only Jourdan who did it. I’m talking about adverts. For editorials there were totally crazy things. There were also daring advertisements done at M.A.F.I.A. for Saint Laurent.

When you say he worked quickly, what is quickly for a collage like that?

FS: I don’t know, a day?

TL: And the size?

CPC: They came in different sizes.

Did he ever change the size of the elements he’d cut out? Did he ever enlarge them?

CPC: No, not when they were photomontages – they were almost always practically the original elements. When he worked in black and white, for his montages or for his poster maquettes, he used to play around with them more – transform the elements and change the size.

FS: Just looking at the photos I’d taken with the photographer, when you look at the light it’s completely integrated, it’s super well done. So even in his research he had to find just the right light according to the leg he’d chosen.

And when he delivered it to you was there a story to go with it? He gave it a title, so I guess maybe there was – Roman spoke a lot didn’t he…

FS: Yes, but he didn’t sell his thing.

TL: No that’s not what I meant…

FS: He’d make a joke…

CPC: He collected quotes, lots of them and would invent titles – he loved doing that, even before he had started working on a piece. He often made a montage because of a title he already had.

That corresponds with the surrealist school, with the cadavre exquise4 and so on… Do you have any anecdotes you could share with us?

CPC: What I can tell you is that at that time he was working very hard; he was very prolific. And he worked alone. For example the Beaubourg [The Pompidou Centre] catalogue, he did on his own. He worked all night. I would sometimes help him. The texts would come on rolls of paper and we had to stick them onto cardboard. He did everything himself. He had an assistant occasionally.

TL: Did he cut using scissors?

CPC: Yes always scissors and Kleer Tak, which damaged the original copies terribly. But he wasn’t interested in the originals; it was the final print that interested him. Roman would put the originals to the side but if they appeared in the press sometimes he would cut them out, put them in a frame and sign them. He’d sign the prints. For him that was the oeuvre. He was more interested by the work that was shared.

Frank, after Jourdan did you ever work with Roman again?

FS: No. But it’s hard to use the same style for another brand.

And did he have any other fashion clients after that?

CPC: He did something for Vuitton. Not a campaign, but he did a catalogue which had images, photomontages. He also did a campaign for Galeries Lafayette for which he he took a small hand-drawn sketch and blew it up – that was fun. No other fashion people after that though. He worked a lot in every possible direction. He was prolific. But at the same time you didn’t really notice that he partied too. He wasn’t obsessed. He enjoyed it.

FS: [To Chantal] How old was he when he died?

CPC: Sixty-six. He was young. It was in 1996, nearly 20 years ago. [To Frank] He was very vibrant, very fun – I don’t know if you found him funny – but he was very funny.

FS: Yes. I was intimidated by him but he always had something kind to say. He was super sophisticated which went perfectly with his image and his work.

CPC: I’ve never met anyone like him since, he was extremely joyous but at the same time very nostalgic. He went from one emotion to the other; it’s a very Slavic characteristic.

Were you one of his pupils?

CPC: No, not at all. I met him at a party in 1979. And I lived with him from 1980 onwards. For me, his work doesn’t age. Every time I see it in an exhibition, it remains so fresh and alive, very modern and current. He was so natural in his work – he had just the right balance. Towards the end it became more radical and political. During his lifetime, he set in motion a whole school of design. Today, I still see images which are directly influenced by his work.