Stefano Pilati on suits versus sportswear, and the shifting male psyche.

By Jonathan Wingfield

Photographs by Pieter Hugo

Sittings Editor: Jerry Stafford

Stefano Pilati on suits versus sportswear, and the shifting male psyche.

Menswear is booming! So we’re constantly told. On one hand, the sector is generating some of the fashion industry’s most significant financial results, thanks, in part, to a sizeable demographic of Asian men embracing ‘metrosexuality’. On the other, menswear designers are currently experiencing a period of creative liberation, redefining notions of masculine style and identity, with a notable shift towards more casual, sports-influenced garments. Thus, we find ourselves with historically ‘classic’ brands proposing skate skeakers, printed t-shirts and performance outerwear where only a few seasons ago, they were continuing to champion a more traditional menswear aesthetic and lifestyle.

This begs the question: are menswear brands aiming to capture younger consumers? Or are they proposing that older men – those generally with more financial muscle – dress in more youthful ways? In turn, is this shift towards more casual menswear attire affecting the sales and status of classic men’s tailoring? And what is all of this doing to the male psyche?

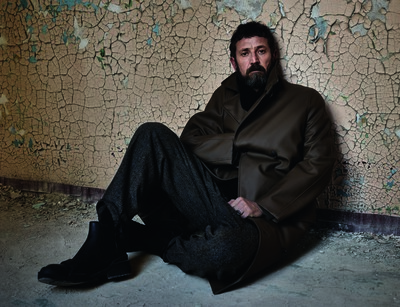

We turned to Stefano Pilati to answer these questions. A pure product of 1980s Italian fashion, Pilati scaled the industry via a deep-rooted appreciation of cloth and fabric. Rising through the ranks of Cerruti, Armani, Prada and Miu Miu, it was his eight years in Paris at Yves Saint Laurent (initially under Tom Ford, then as overall Creative Director for women’s and menswear) that brought him wider fashion recognition. Here was a designer whose personal style not only made him the perfect ambassador for YSL’s modern menswear, but he soon became the poster boy for a new era of, as he calls it, “male vanity”. Bearded, never flashy, yet self-assured, Pilati looked as memorable in three-piece tailored suits as he did Comme des Garçons track pants.

The YSL era was nevertheless a turbulent time for Pilati, with his forward-thinking and conceptual take on the hallowed Parisian house ruffling the feathers of sceptics and traditionalists. When, in 2013, it was announced he was joining Italian house Ermenegildo Zegna – the biggest menswear business in the world – as Head of Design of Ermenegildo Zegna Couture, and Creative Director of the house’s newly revitalised womenswear label Agnona, it immediately felt like a neat fit. A major manufacturer of luxury textiles and suiting for brands like Gucci and Tom Ford, the company’s own Ermenegildo Zegna label provides classic tailoring for men the world over.

Pilati’s appointment answered Zegna’s need to align itself with the creative renaissance at the heart of contemporary menswear, and presumably the designer’s long-standing passion for fabric, Made in Italy, made him the obvious candidate. Installing himself and a core design team in Berlin, Pilati retreated from the public eye and let his work for Ermenegildo Zegna Couture speak for itself. Universally well received, his collections have pushed the brand into new territories via high concepts, exquisite and experimental fabrics, and a deconstruction of formal menswear into something more challenging and representative of the times.

System travelled to Berlin to question Pilati on the changing face of menswear and how he’s helping Zegna navigate these changes. And always one to enjoy the visceral nature of dressing up, he agreed to model the latest Zegna collection for South African fine art photographer, Pieter Hugo.

Jonathan Wingfield: You’ve often said you design menswear with yourself in mind. So when you’re designing for Zegna, the world’s biggest menswear business, does that put a lot of pressure on your own personal taste and wardrobe needs?

Stefano: I’m obviously aware that whatever I might experiment with on myself isn’t necessarily going to be valid for everybody else. You know, I am a 50-year-old man, sat here wearing floral pants and, frankly, not many other 50 year olds can get away with that. This is where I have to take a step back and realise that when I’m designing for Zegna, my own evolving tastes need to be grounded in some level of objectivity.

But the influence of your personal style has certainly been felt over the years.

Stefano: Well, I’ve been sporting a beard for 20 years and now everyone seems to have one; I’ve been wearing short-legged pants for 20 years and now everyone wears them; and I’ve been talking about male vanity for 15 years and these days, men shave their eyebrows. So with time you can see how my personal instincts might get filtered down to a wider public. But it never starts with that ambition.

‘I’ve supported sportswear for a long time but it doesn’t give men status. The rise of casual wear shows we are suffering a paradox around luxury.’

When you first arrived at Zegna, did you take the conscious decision of translating your personal style towards a global menswear proposition?

Stefano: As I said, for almost 20 years people have seemed to relate – or at least react – to the way I dress. And they want to wear what I wear. So at some point I had to take this into account and say to myself, ‘Okay, so maybe let’s go for it: this is what I want to wear, this is what I like and now you can have it too.’ This seems to me more honest and natural than engineering a self-imposed personality in order to market fashion, or even market myself, which I’m not good at doing. I can bring myself to the collection but I can’t really see myself trying to create an entourage of acolytes that will dress like me.

So who’s the man you design for?

Stefano: I’ve always designed for grown-up men. I’ve never been interested in addressing youth culture through fashion. As far as I see it, young people need to create fashion for themselves, by themselves. You can’t be an older designer telling kids what to wear, that’s just an ego trip beyond belief.

Yet isn’t that exactly what designers seem to be turning to these days — menswear has never looked so sporty and youthful.

Stefano: I’d rather put myself out there – as the vehicle, the opinion leader, the designer, a 50-year-old man – to express my values and Zegna’s values and hope that men might connect with them. That is where the tailoring, the quality of the fabrics, the manufacturing, the newness, even the romanticism, all play a part in expressing this.

To what extent does a menswear designer have to understand the male psyche?

Stefano: It’s essential. Nowadays I find that men’s rapport with fashion is underlined by paradox. Men want to feel as though they are acting individually in the way they dress, yet at the same time they don’t want to be noticed too much. They want a fresh look but they want to follow vestimentary protocols.

You mentioned before that men now shave their eyebrows. What have you learnt about evolving male identity: how men now see themselves, how clothes can bring about these shifts?

Stefano: I grew up in the 1980s: middle-class men were working in banks and were very respectable; there were individuals with basic options to dress in certain ways, but they had to wear a tie every day. I remember that at one point, in the second half of the eighties, these same men started going to work wearing a polo neck, losing the tie – and that was already considered revolutionary. This evolved into chinos and a jacket, which pushed things even further. This shift from pure tailoring to more relaxed dressing triggered the shift towards sportswear and outerwear and leisurewear.

So it was predominantly a middle-class shift.

Stefano: Yes, and because this shift was so synonymous with the middle classes, then the very upper class had to distinguish themselves in different ways: for example, you could confine yourself to the strict protocol of tailoring, the dress code of those who were dealing with the real money and real power. This was the upper class basically saying, ‘We’re almost blissfully unaware of what’s happening to the middle classes.’

Besides strict tailoring, what other ways did upper class men distinguish themselves?

Stefano: Alternatively, they just went totally nuts and started wearing silk shirts and gold buckle sandals [laughs], almost celebrating the fact that they could work from their mansions.

What about your own rapport with wearing suits these days?

Stefano: It is funny because when I started working at Saint Laurent I was wearing three-piece suits every day, and I loved it. Then it slowly dawned on me that I didn’t quite feel myself anymore. I started to feel that I was looking older than perhaps I should, and I kind of fell out of love with the ritual of dressing in three-piece suits.

How did this shift affect your own sense of status, if at all?

Stefano: To tell you the truth, I didn’t like the idea that people were taking me more seriously simply because I was wearing a suit. I felt I needed to acquire that authority through what I was doing rather than the suit I was wearing. I know that sounds crazy coming from a Zegna perspective, but as I mentioned before, my own evolving tastes have been informed by many years of experimentation in clothing. Anyway, I decided to abandon the suit… and it seems that everyone else did the same.

‘Sure, fashion is frivolous – we’re not saving lives – but I feel that at Zegna, exploring eco-sustainability is more relevant than creating a rock star look.’

In favour of more casual wear?

Stefano: Right now, I don’t exactly know where male identity is going. I have been a supporter of sportswear for a long, long time, but this doesn’t give men status – and rich men want to show that they have options and possibilities. Once again, it illustrates how we are now suffering a complete paradox around luxury fashion.

Luxury just seems to be a word that gets used in association with fashion – any fashion – in an arbitrary manner.

Stefano: Yes. They are all apparently luxury brands and I cannot stand that anymore. There is a side of me that rejects all that, yet another side of me actually embraces it, in the sense that all this research at Zegna that I spend on the culture of tailoring absolutely should count for something; it should be considered as a status symbol. But, you know, the moment that you do something like that, then people want to sell it in 500 stores and be successful and influential; they want to introduce it to a segment of the market that might comprehend the word luxury but doesn’t really care to embrace it.

You mean, the middle classes?

Stefano: Right. The middle classes don’t give a fuck about luxury. They want a good quality/price rapport, they want to be comfortable, they don’t necessarily want to be seen, they don’t look for a statement or great status in what they wear – and they represent a big slice of spending power. The reality is that because we are addressing other countries with lots of money, notably China, that means we can keep this level of luxury understanding high, but it is very complicated now.

But what are you questioning here: the meaning of luxury or the need for luxury?

Stefano: I keep asking myself this question on a daily basis. And to tell you the truth I don’t always end the day with answers. So my comfort zone is simply about staying true to myself and true to Zegna. I feel I’m doing the right thing, and that it corresponds well to the brand I work for.

What role do you think the suit plays in contemporary life?

Stefano: I think a suit still has the role it’s always had; it has the role of being formal. It is serious attire; a man in a suit always has authority, he still has it. You can be an employee at the post office or a bus driver, or you can be an auction bidder, wearing a suit shows authority, and that is why I will always respect it, no matter what my personal fashion sensibility is at the moment.

How do you feel about the migration of so many classic – often Italian – brands now presenting collections that are either designed for a more youthful consumer, or proposing that elder men dress more youthfully, more casually, more informed by streetwear?

Stefano: Everyone talks about sportswear, but what does that actually mean? It basically means we are all wearing duvet jackets, god knows how many of them I have. But I’m not convinced there’s any real elegance in those garments.

So why are we all wearing them?

Stefano: Because we want comfort.

Has comfort taken over from formality, authority, even elegance?

Stefano: It clearly has.

And do you think that is an irreversible shift? Every man wore a hat in the 1950s, but since the 1960s revolution that ritual has simply disappeared. Do you think that the current ‘casual revolution’ in menswear – if we can call it that – is an irreversible shift?

Stefano: I would say so. I’d be surprised if it wasn’t.

And what does that do to male identity on a broader level?

Stefano: The suit remains a statement of fashion authority and it can be projected as something very sexy. But that doesn’t mean that if you wear a duvet jacket or a leather jacket you cannot be sexy. So even the sex appeal projected through men’s clothes is now far more eclectic – it is quite random, as life is today, and therefore more challenging.

How does this shift in formality affect you as a designer?

Stefano: Principally, it gives me freedom. I mean, what is the point of being a fashion designer and only proposing suits, shirts and ties? So this freedom leads you to explore new possibilities: new cuts and new fabrics; knitwear and sportswear become very important, overcoats, shoes and extra accessories take a new role. So from a designing point of view it is not frustrating at all. It is actually the opposite.

‘I’ve never been interested in addressing youth culture through fashion. Young people need to create fashion for themselves, by themselves.’

Part of Zegna’s allure, and certainly a significant part of its global business, is the company’s prowess when it comes to developing and manufacturing fabrics. Just to go back in time for a moment, how did cloth and fabric play a specific part in your understanding and appreciation of fashion as you were growing up?

Stefano: When I was 17 I quit school and decided to do an internship at Cerruti. While the main design office – what I probably considered to be the sexy part – was based in Paris, the manufacturing and diffusion departments were in Milan. The diffusion division was driven by tailoring and fabric, and my internship started by assisting the director of the specific department that selected fabrics. The suppliers would come in to show us all the new fabrics and, partly to teach me and partly to test me, my boss gave the task of putting dots on the fabrics that I liked the most. Quite naturally, I happened to choose the ones that were perfect for the following season’s collection. Straight away, both my boss and the suppliers found it remarkable that someone so young had such a developed eye and a tactile sensibility for this.

What do you think informed that skill?

Stefano: I honestly don’t know. I think just pure instinct, as I have no background in my family for fashion whatsoever. Fashion and clothes obviously intrigued me but I had no formal training at all. So it my boss at Cerruti who really taught me the importance of how the choice of fabric could completely inform the type of fashion you want to create.

That’s quite an Italian thing, right?

Stefano: Well, the same school of thinking is at Armani, too; Giorgio Armani worked at Cerruti before setting up his own company. So even if a pure design studio – like the Cerruti one in Paris – was probably more appealing to me, the reality is that I had been immersed straight away in a very hands-on approach to fashion, based on a real understanding of fabric; which in turn led me to understand how choices of fabric could shape a fashion brand’s identity. Over the following years, this took me first to work at Armani and then to Prada, as my ambition turned to becoming a full designer.

Were you hired as a designer at Prada?

Stefano: I started as a fabric researcher, but all the fabrics that I was selecting to show Miuccia [Prada] or Mr Bertelli were very much in line with how I understood their research for the collection. I was already considering design as well as fabric research. So everything came quite organically.

Presumably the rapport between fabric and pure design is key to your role at Zegna.

Stefano: These days, the visual aspect of the clothes and the approach to designing a collection has changed. I used to say that clothes talk – when you choose a nice fabric, the behaviour and aplomb of it inspires you with the designing. Now it is more a question of, ‘Is it light enough for the Middle East, or for the humid countries? Is it inter-seasonal because the collection needs to stay on the boutique floor for four months, six months, or eight months?’ That tactile relationship with fabric still exists, but it’s become far more subliminal. These days, I force myself not to fall in love with fabric research, because then you find yourself placing too much importance on something that people don’t really care about. You know, as long as it is a nice colourful dress that you can buy in Miami… But, you know, that’s fine, too. I can accept that. And to be honest, in menswear there still is that research element that men value, particularly when you start to think about performance outerwear garments.

It strikes me that the themes you’re exploring in your Zegna collections – science, industry, urbanism, power, the ecology – seem like the themes that men should all be exploring in our lives. Yet these themes seem almost at odds with the realities of what most menswear brands – and perhaps men in general – seem preoccupied by. Do you feel that what you are proposing is actually quite marginal even though it presents basic realities? And is that marginalisation a luxury now?

Stefano: That was what I was about to say; maybe in the luxury market these themes are marginalised. But to be luxurious we need to be sensitive to a different level – ethically, intellectually, even sentimentally. I still suffer from this sense of shallowness that we give to fashion, so I am always looking to elevate both myself as a fashion designer, and fashion itself, to something that is more relevant to our lives and surroundings. You know, this is fashion – I’m not saving lives here – but I feel strongly about attaching what I design to contemporary life and social themes. Sure, fashion is frivolous, but I just feel that for Zegna, exploring eco-sustainability is more relevant than making a rock star look.

‘Even the sex appeal projected through men’s clothes is now far more eclectic – it could be a suit or a duvet jacket. It’s quite random, as is life today.’

Again, this seems at odds with contemporary fashion’s increasing reliance on archive source material.

Stefano: Well, everything has been done in fashion, so we’re dealing with refinement more than giant new steps. But I feel strongly – ethically, as a designer – that you shouldn’t simply repackage what has been done before and sell it as something brand new. That whole approach to fashion reminds me of that MTV show, Pimp My Ride, when they get a vintage car and do a makeover of it. Of course, I understand why that makes commercial sense – human beings naturally find it easier to comprehend and recognise what we’ve experienced before – but I want to take a risk doing something new.

Have you found yourself challenging the values of Zegna?

Stefano: In a positive way, yes. I don’t want to be the first of the class here. But I don’t want to be the punk of the company either. I just think it’s my role to shake things up a bit, within a reasonable frame of intelligence. I think I’ve given the company another audience, and with that comes another level of criticism, another level of investment, another level of the unknown. And for a company like Zegna – where everything is calculated to precision – anything unknown can be really destabilising.

People seem intrigued by the fact that you’re based in Berlin. What advantages does this have for you?

Stefano: It keeps me out of the corporate daily life of the company, which is how I think it should be. And it takes away a lot of the pressure. You know, by my nature, I am a very isolated person. Not only do I isolate myself in this non-fashion city, but I live and work in the same building, and I spend weeks when I don’t go out. All this gives me a great detachment; it reminds me of something Mr Bertelli said to me when I started at Prada: ‘The best research takes place in your mind, not on ‘inspiration’ trips.’ Of course, you can get inspired by all sorts of things, but that sometimes shifts the focus away from newness. We now live constantly immersed in our memories – especially as we get older – so it is nice not to stimulate them too much.

Do you think the way that fashion is still presented seasonally is out-dated?

Stefano: It is not relevant. I am very much against it, but frankly it is bigger than me. Why do we even continue to label the collections Autumn/Winter? I would rather think about occasions: you know, ‘This is the look I would wear to talk to the teachers of my kids,’ or ‘this is the outfit I would wear for a ceremony’, specific to time and place. Being someone who has a lot of clothes, the real fun comes from exploring all those situations; elegance comes from choosing the right tie for the right occasion and feeling comfortable in it.

Do you see yourself working in fashion for a long time?

Stefano: I would like to think so, but I don’t know. You cannot be a fashion designer unless you are giving literally all of yourself, every day. It is a very particular job because your taste, your reputation, your life, can be reflected – and judged – in the choice of a button. But you can change people’s lives, so I take it very seriously.

How do you personally quantify the success of your collections?

Stefano: Taste. People can criticise my collections from different perspectives, but something that cannot be criticised is taste. If you work in fashion, you need to have good taste otherwise what is the point? I refine my style through refining my taste on a daily basis, and this isn’t something that necessarily comes from research or development. You can find taste in an abstract painting, in car design, in a novel, or in a documentary. So when I quantify the success of my work, it is through the level of taste I have managed to bring into it. And that, I think, is… unquestionable [Laughs].