From selling sponges in his car to conquering China with a monogram, Yves Carcelle tells all.

By Jonathan Wingfield

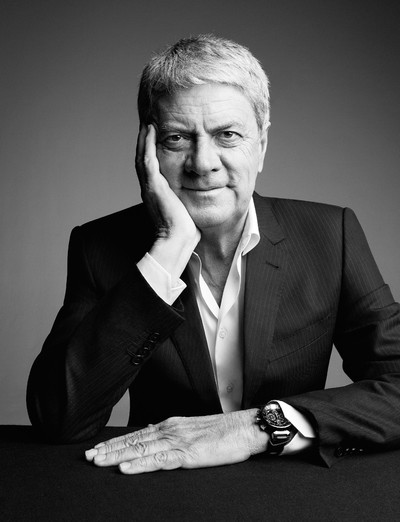

Portrait by Patrick Demarchelier

From selling sponges in his car to conquering China with a monogram, Yves Carcelle tells all.

This is the story of the CEO who had Madonna, Steve Jobs, and any number of Coppolas on speed dial. The CEO whose advertising campaigns featured Mikhail Gorbachev posing in front of the Berlin Wall. The CEO who embraced China when most others only had eyes for the West. But Yves Carcelle was never an ordinary CEO. Between 1990 and 2012, as top dog of Louis Vuitton, he oversaw the lightning quick expansion of the brand and was instrumental in breaking new ground: appointing Marc Jacobs as Creative Director in 1997, launching a prêt-à-porter line, and reinventing the company’s leather goods with distinguished collaborations and a succession of ‘it’ bags that have changed the face of luxury forever.

With a retail portfolio that’s grown from 117 stores in 1990 to a whopping 462 (and counting) worldwide, Carcelle has transformed Louis Vuitton and its ubiquitous LV monogram into one of the worlds’ most recognisable brands. Research agency Millward Brown’s 2012 study ranked Louis Vuitton as the world’s 21st most valuable brand as well as the most valuable luxury brand – towering above the likes of Hermès, HSBC, BMW, Shell and Amex – and estimated its worth to be $25.9 billion. Mind-boggling facts and figures aside, it’s always been said that Carcelle was a much-liked and respected boss by his 22,000 strong worldwide staff at LV. Indeed, it’s a jovial Carcelle that welcomes System into his office deep in the heart of LVMH HQ. Switching off his myriad iPads and smartphones, he settles back into a comfy execuchair and asks, ‘Right, where shall we start?

You were born in post-war Paris, light years culturally from the world of Louis Vuitton. Can you describe the Paris you grew up in?

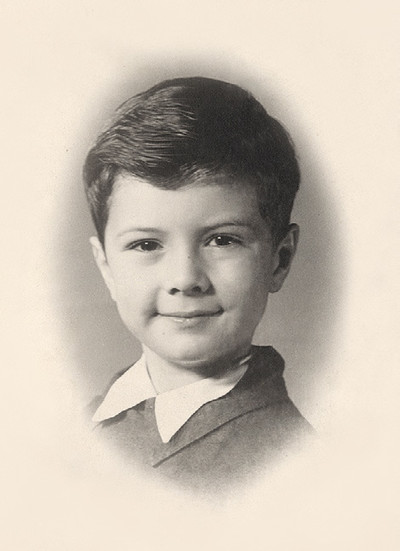

Yves Carcelle: I am a pure Parisian product. I was born near Faubourg-Saint-Denis, my parents lived in the Latin Quarter, and I spent my entire childhood with- in the vicinity of Pont Neuf and the rue St Benoit – where my nursery and primary schools were – then to the Lycée Montaigne. You couldn’t have had a more typical Parisian childhood if you tried. Wednesday afternoons were spent wandering around town with my school friends, so I know the place like the back of my hand.

What about your family life?

I come from a modest family. My father was a civil servant in finances. My parents were very, very nice, but for an only child like me, they were a bit stifling. It’s quite rare to live in the same place for 18 years, and I’m sure that triggered a longing to go off and discover the world.

What were your first experiences of travelling abroad?

Like every other French school kid at the time, my first trip abroad was to England on an academic programme when I was about 13. It was a rite of passage, like in that film A nous les petites anglaises! [Let’s Get Those English Girls] 1. Later on, when I was 19, I went to Cameroon with a backpack and my friends, which was a wild adventure. The following year, I went to the Indian Ocean, and I’ve been travelling the world ever since.

Were you a straight-A student, rebel or slacker at school?

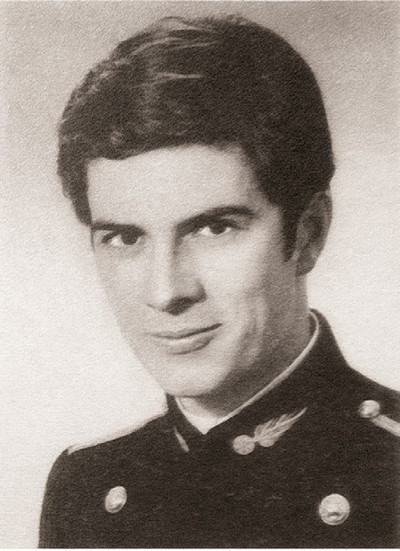

I was good overall, but at the same time I didn’t always fit into the mould of the model student. I always did well at maths and that helped me get into X [l’École polytechnique] 2 when I was 18, which made me the youngest in my year.

X has historically been the breeding ground for France’s great industrialists and highest-level civil servants. What did it feel like attending this elitist centre of excellence?

To be honest, I still feel great pride because it’s a school with a history: it was established during the revolution, it was militarised by Napoleon… Even if it sounds ridiculous, the motto was Pour la Patrie, les Sciences et la Gloire [For Homeland, Science and Glory], and we all felt a sense of privilege. On the first day I arrived, however, everything in my life changed. I clearly remember saying to myself, ‘I won’t ever become an engineer or a researcher or a civil servant’, which was what’s expected from the students. In fact, I told myself that so often that I didn’t achieve much. By the time I left, I felt completely disconnected from the professional and social network that that kind of education provides you with. I think I always considered myself a bit out of the norm, which is probably why I was reluctant to accept what education expected of me.

‘I found myself on the road, literally selling sponges and window cleaning products out of the back of my car.’

What did you have in mind if you weren’t prepared to work for TGV or France Télécom?

Around that time – this was the end of the 1960s – ‘marketing’ was just arriving in Europe. I’d read magazine articles about the big American consumer companies like Coca-Cola who weren’t simply selling a product; they were try- ing to better understand their customers and the environment in which they existed. It was a real eye-opener.

What was consumer culture like in France at the time?

Companies like Danone were just starting to get interested in marketing. Around the time I started work, the French discovered supermarkets and mass consumption, which suddenly made everything seem possible. Don’t forget, this was les trentes glorieuses. In today’s climate, it’s difficult to comprehend the excitement of a booming nation… and then 1968 happened.

Were you on the frontline of student protestors?

Living in the Latin Quarter meant we were in the thick of the action. We’d go out every night to stand by the barricades at the bottom of the rue Saint- Jacques. Witnessing the wrongdoings of the state and experiencing the reaction from revolutionary minorities left a huge impression on me. For the vast majority of French youth, and even people from the older generation, there was a feeling of everything being possible. Beyond the anecdotes of throwing rocks and rioting, it really was collective liberation. People in the streets would stop and talk to one another.

Without sounding flippant, how has that so-called spirit of May 1968 influenced a CEO of Louis Vuitton?

People from that era who have subsequently gone on to have managerial positions are probably quite different to other generations of managers. I think it comes down to collective proximity and simpler rapport with one’s peers; it was an irreversible factor that resulted directly from 1968.

Let’s go back to your early working days. You’d just left X and decided you didn’t fit the mould of public sector industry.

As soon as I decided I wanted to enter the private sphere, I had the idea in mind that I wanted to run a company. I didn’t know who, how, what or in which country, but I knew that’s what I wanted to do. My first move was to answer classified ads that weren’t at all aimed at university graduates, and I found myself on the road selling cleaning products for a company called Spontex.

That must have been a culture shock for one of the educational elite.

My friends couldn’t believe I’d become a travelling salesman! Literally selling sponges and window cleaning products out of the back of my car. But it changed my life forever. Because every single working day since has incorporated this notion of selling: selling to your bank manager, selling to your boss, your colleagues, your customers… So having learnt it first-hand by knock- ing on doors brings incredible experience that you’ll never get from traditional education.

Were you one of these natural-born entrepreneurs who sells his football stickers in the school playground?

Yes, that was me exactly, but my ‘product’ was marbles. I’d ask myself, ‘What’s the best technique for increasing sales?’

Do you think one is born a salesman?

I think so, yes, but that’s not enough. You can have a certain aptitude and the desire to sell things, but sales techniques and marketing are things you have to acquire and develop. It’s like anything: you can have a sporty physique but if you don’t train…

Is selling in the Carcelle family DNA?

No, not at all… if you take my father and grandfather, there’s no history of it.

Who was initially responsible for teaching you in a professional environment?

The director of sales at Spontex, who was my boss, was an old hand at managing his team of sales reps. He didn’t exactly hold me – this young graduate from X – in high esteem at the beginning, though he helped me professionally, and I learnt a lot from him. But per- haps most importantly was the military service we had to do back then. Having done X, I automatically became a young lieutenant in charge of men 20 years my senior who’d served in Algeria or the Indochina War. It forced me to think about how I was going to impose myself on people, whatever their relationship with me was.

Has that scenario played itself out in your business career?

Constantly. I think luck is having experiences that mature you. That’s why I’ve always encouraged young people who want to start working at Louis Vuitton to go and get a year’s experience as a shop assistant, or as a manager at one of the ateliers. It transforms them and pushes them to go further, but at the right pace. There’s no point in trying to become LVMH’s Director of Strategy within your first year – it won’t really do anyone any favours.

Let’s go back to your sponge-selling days…

After a few months I worked my way up to being Spontex’s Product Manager. I then did an MBA at INSEAD business school, before five years as marketing and commercial director at a German group called Blendax whose business was toothbrushes and toothpaste.

In Germany?

No, at their French headquarters, but that’s how I learnt to speak ‘survival German’. Being part of a foreign sector back then has obviously had considerable benefits to me ever since. There’s an obvious obstacle – a cultural one – that you have to overcome if you are going to manage international affairs.

Did the fact that you were working with such mass-produced, everyday items make you want to explore rarer, sexier, more ‘noble’ sectors?

No, to be honest I had no idea which sector I wanted to go into. But by the end of the 1970s, I really wanted to manage a company myself. I’d been learning all these techniques for nine years, and I wanted more responsibility. At that point it could have been anything, and it was total chance that I got involved in textiles. In 1979 a head-hunter offered to place me as boss of Absorba, who were based in Troyes. At the time no one wanted to work in textiles because it was a sector in decline, and it also meant working in the provinces…

So what was the Absorba attraction?

While I wouldn’t dream of comparing it to couture, it was a total revelation for me to be working with creative people. With all the excitement associated with creativity – even when you don’t ‘create’ yourself but you’re fascinated by creation – there really isn’t a better job. But it was totally by chance; I never said to myself I’m going to work in fashion. It just so happens that from that point on, I never left this industry.

Was it difficult to acclimatise to creative culture when your background was straight up business?

I think you either have the temperament or you don’t. When you work with creative people, you have to accept that you share the power. It’s not just a question of green-lighting a toothbrush! At a company like Louis Vuitton, you are obviously surrounded by creative characters – designers, artistic directors, stylists, architects – so you’re constantly dealing with their world.

What was it that led you to move on from Absorba? Creative limitations or lack of business ambition?

When the product began to be distributed further afield, I wanted to open stores, but the then-president didn’t agree. That led me to leave and join Descamps where I had 240 franchises to oversee. Then, when I arrived at Louis Vuitton, I told myself we could have total control over distribution. When you start overseeing an operation to that level, you see how creative input has an effect on everything: the product, the store interiors… For me it was a long period of maturing: from my first ever experience in children’s clothing to becoming the idéologue who takes control of everything that Louis Vuitton didn’t already control ourselves.

Once you get involved in textiles are you naturally attracted to the luxury sector for its quality and noblesse?

Not necessarily. Look at the success of Inditex and Zara: Amancio Ortega is a man I admire a great deal, and he’s never left his niche. So I don’t think we’re necessarily forced towards luxury. I think if Bernard Arnault had never given me the keys to the proverbial Ferrari, I probably would have stayed in mid-level retail. I was lucky enough though to be given the keys to a six-star hotel in paradise.

Do you remember the first time you met Bernard Arnault?

Yes, one day in 1987 he asked to meet me because he owned Boussac, a competitor. I was fascinated by the intellectual mechanics of the man, and I witnessed at close hand the way he took control of Boussac. At the same time he had this dazzling vision… I mean, he can be demanding at times, but you have to remember that back then very few people ever imagined luxury could become a global industry. That really was Bernard Arnault’s vision. He started off with Dior and Le Bon Marché, then acquired Céline… and that was the beginning of the snowball effect. He saw the opportunity.

What was it about the luxury sector in particular that attracted Arnault?

You know what – I’ve known him for 25 years, but I’ve never actually asked him that question! At what point did he have his eureka moment regarding luxury? Was it before or after buying Boussac, the group that owned Dior? Now I think about it, he clearly had that vision of le luxe when he spoke to me in 1987. But was it already in his mind when he bought Boussac in 1984? That would be very interesting to find out. You should ask him the question…

Either way, you’d have to say his acquisition of Boussac was the turning point.

Well, at the time he was criticised for the way he controlled Boussac, and didn’t hold onto the textiles when everyone expected him to. But if he hadn’t done that, then the global luxury domain, as we know it today, wouldn’t be French. That’s not me being patriotic, that’s simply an objective reality.

You’ve mentioned your fascination with creative people. Does Bernard Arnault share this fascination?

He is definitely interested in creative people – perhaps in different ways to me – but he couldn’t possibly be passionate about his group 30 years on if he didn’t share that fascination.

‘Had Bernard Arnault never given me the keys to the proverbial Ferrari, I’d probably still be working in mid-level retail to this day.’

And is Bernard Arnault as open to the sharing of the power with creatives as you have been?

[laughs] I’ve never thought about that.

Do you remember when he first articulated his vision of luxury to you? Because obviously luxury in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s wasn’t what it is today.

Well, the vision was already there, but it needed the maximum added value with everything we did: the products, the way we communicated, the environment. Bernard Arnault was already talking about Japan even though it was still a very small market. Through the developments in Japan, his vocation became truly international.

When you started at LVMH in 1989, what were you expecting? Bernard Arnault had his vision, what was yours?

Everything I had experienced up until then had had limits. Suddenly everything that I’d dreamt of doing seemed possible, without knowing exactly what, but there was huge potential, in terms of retail, in terms of conquering the world…

Were you given a specific mission or strategy?

When I started, Bernard Arnault had recently arrived, and he needed new collaborators who were ready to head off on an adventure with him. I became the President of Lacroix, which was pretty fascinating because Christian is a wonderful man who I still regularly see – even if at times it was complicated, and there are countless stories as to why things didn’t work out with that particular business. Christian’s main problem was that just after the house was launched, Bernard Arnault started buying LVMH, and I guess the love affair was no longer so exclusive. Once Lacroix came to a close, that very same weekend Bernard Arnault asked me if I would like to manage Louis Vuitton.

What had been your impressions of Vuitton prior to that?

Many of those who’d joined LVMH thought it was a tired house. I was convinced, though, as was Bernard Arnault, that Louis Vuitton had an incredible potential.

At the time Vuitton was only a leather goods company.

But it was turning over more than half a billion euros. It was already good, and then it multiplied…

And its global reach at the time?

There was already a significant presence in Japan and Asia, in part because the Japanese had started travelling everywhere. So luxury items started being sold wherever the Japanese were travelling to. Where Bernard Arnault and myself were in complete agreement was, ‘OK, so we’ve convinced the Japanese, now we need to conquer the world.’ The first store opened in China in 1992.

The term ‘luxury group’ has long since entered fashion and retail vernacular, but back in the 1980s how important was the concept of grouping together quite disparate companies – alcohol, leather goods, fashion, auction houses – to create a stronghold?

You have to remember that LVMH was already a succession of fusions before Bernard Arnault bought it and took the reins in 1989. Twenty-five years ago, most luxury families wanted to remain autonomous and independent, but the Moët and Hennessy families got together. Imagine champagne makers joining with cognac makers, it was quite incredible. Their power in terms of distribution by joining forces was extraordinary. They then bought Dior fragrances. Elsewhere Louis Vuitton fused with Veuve Clicquot and bought Givenchy. On both sides the families were saying it might be worth securing our futures by grouping several activities together. And in 1987 under bankers’ initiatives, the two groups – which were already groups in gestation, actively searching diversification – fused. So both groups had the mindset that you could have several vocations while respecting each house and each vocation. This fusion only strengthened that notion. Bernard Arnault arrived, he already had Lacroix and Le Bon Marché, then Céline and Kenzo joined the expanding galaxy.

What did Bernard Arnault bring in terms of ideology that someone else might not have done?

I think it’s something that is very personal to him: when he wants something he will do anything to get it.

It has certainly worked.

If you really believe in something, then give it the backing it needs. An example I often cite is that very early on, in 1990, I proposed a strategy to him which involved a continued growth in travel and leather goods. At the time we didn’t have much leather and there weren’t enough lines. We also had numerous geographic territories to conquer outside Europe, America and Japan. So we both agreed that Louis Vuitton should aim to become a global brand, but not at that particular moment in time. We agreed to discuss it again five years later. Then, in 1995/96 we launched an operation with the monogrammed canvas, collaborating with people like Alaïa, Vivienne Westwood, Isaac Mizrahi… The world discovered it and the fashion industry agreed that the Lou- is Vuitton monogram was something magical. That was when we said, ‘Ok, it’s time to launch a global brand.’

So that really marked the beginning of Vuitton as we know it today.

Yes, exactly. At the end of 1996, we agreed that the time had come to establish Louis Vuitton as the global leader in leather goods. For several months we were contemplating maybe launching a pair of loafers or a jacket as a means to subtly broaden the product range. But then one Monday morning, Bernard Arnault said to me, ‘I’ve been thinking all weekend, we’re the global leaders in leather goods, there’s no point adopting a softly approach, why not create an entire prêt-à-porter division? We should get an artistic director and do a show for the first season… We’ll amaze everyone.’

Did that suggestion really come out of the blue?

Completely. For months we’d been say- ing how we were going to take things slowly. The conversation continued, and I said to him, ‘Have you already got an artistic director in mind?’ And he answered, ‘Well, he’s completely the opposite end of the spectrum to Louis Vuitton, but he is a very clever guy, so I think you should call Marc Jacobs.’ So I went to my office and called him: ‘Hi Marc, it’s Yves Carcelle, Louis Vuitton CEO. Would you be available for a conversation about possible collaborations?’ I went to New York that week, and it all started from there. I didn’t see anyone else, only Marc. Although Arnault had said all of that to me, he’d done it with an air of not being totally convinced that it was the right move.

‘You need a sensibility that allows you to translate creativity into business, but when the CEO starts thinking he’s creative it’s the beginning of the end!’

Can you describe the atmosphere when Marc Jacobs first arrived?

I’d done the deal with Marc in New York and then invited him and his partner Robert Duffy to come and see us in the office in Paris, which at the time was located in the La Grande Arche at La Défense. On the first day they arrived they went off to make some calls to New York, and then Marc came over to me and said, ‘Ok, so where do we work?’ I said, ‘Oh, you don’t like it here?’ And he explained that most days they would arrive later in the office than ‘the suits’, but they’d often work very late, so there was no way his design team could leave at 3am only to find themselves stranded in the middle of this concrete urban jungle! So we instantly got in a car and went to find something in the centre of town, on the Boulevard Raspail. At the time we’d already started the construction of the Louis Vuitton headquarters at Pont Neuf, so the day it was completed, I told Marc, ‘You’re now moving back in with us.’

When did you first sense that the introduction of prêt-á-porter was going to have a major impact?

February 1998 was unbelievably intense: in the space of three weeks, we all moved to Pont Neuf, in the heart of Paris, which was a big deal; we opened our first global store on the Champs Elysées; and Marc did his first show. Then we opened a store in London eight days later. That was when the gamble began to pay off. You have to remember that Louis Vuitton had never exist- ed according to the rhythm of the fashion seasons before. We would launch a bag with a 10-year life expectancy.

How did that impact manufacturing?

Oh, there was deep questioning going on. But it didn’t happen from one day to the next. There’s no doubt that Marc’s arrival brought everything together; today there aren’t two Vuittons, there is only one, which expresses itself through all these different professions.

How did Marc Jacobs’ arrival impact your position as CEO?

Initially it meant a bit more creative compromise!

Was that a shock to you?

I’d thought I was ready for it, but you know…! We agreed from the off that he had carte blanche for the show; that was his territory and I would never interfere. He knew the size of the house and he never tried to claim control of everything – unlike other people.

Nonetheless, did you freak out when Marc Jacobs arrived one day with the idea of getting Stephen Sprouse to graffiti the bags?

Well, he didn’t present it exactly like that. Marc knew the culture of Louis Vuitton well enough; he’d spent months going through the archives, visiting the ateliers. He said, ‘Right from the beginning, people have painted their initials on the trunks, it’s an integral part of the house DNA.’ He said he wanted to revisit this tradition but in a modern context, in street language, and collaborate with an artist. By presenting it like that, it happened effortlessly. I think it was the first powerful collaboration.

Considering the success of the Sprouse collaboration, were you actively pushing Marc Jacobs towards future collaborations with artists like Takashi Murakami?

Murakami derived from an approach that wasn’t overly thought out. We first discussed the idea in 2002, just a few months after 9/11. Marc said to me, ‘As a New Yorker, what has happened has really affected me, it’s really affected my neighbourhood, it was my show that got cancelled… we can’t carry on like this, we need a revolution. So I’m warning you now that my next show is going to be an explosion of colour and naivety. It might shock you, but that’s how it’s going to be. That’s how it has to be.’ He then said the message would be even more powerful if he were to collaborate with an artist. That’s when Murakami’s name came up.

Were you pleasantly surprised by his choice of artist, what with Murakami being an artist from the Far East?

No, that had nothing to do with it. Nothing at all.

But it must have had a commercial impact. I remember going with Marc Jacobs when he first visited Murakami’s studio in Tokyo and realising the cross-cultural significance and commercial potential it was going to have.

But at the same time, he could have easily done it with Jeff Koons, and it would have been just as strong. He needed a ‘factory’ artist for the scale and Takashi perfectly suited what Marc was looking for at the time.

As someone who’s obviously worked closely with Marc Jacobs for many years, what would you say is his greatest talent?

Marc has an incredible ability of sensing the zeitgeist and transforming it into this thing called fashion. It’s as though he has antennae, which give him this perception as to how the fashion world is going to be in six, nine, 12 months time. He is so in the zeitgeist that sometimes his world is almost too ephemeral.

You mean, he’s already moved on to the next idea before you’ve had a chance to commercialise his creations.

When you talk to Marc a day or two after the show, he’ll often tell you that if he did it today, it would be something completely different. I mean, it’s only 48 hours later, but he’s already absorbed something else and moved on.

And his biggest flaw?

He smokes in the office! [Laughs] He gave everything up, drugs, everything… but the fool continues to smoke!

Which of his creative proposals has had the greatest impact on the company?

I think that would be when he invented patent leather, at the end of 1997. When we took him on we assumed that he would be the man for prêt-à-porter and fashion, but that he wouldn’t really get involved with the leather goods. But within just a few days he’d immersed himself in an evolution of the leather goods by inventing a patent leather that was totally in keeping with the monogram, yet incredibly modern.

Was that another of his carefully planned revolutions?

I will always remember it because it dates back to the time his office was on the Boulevard Raspail. We’d often go for lunch in a little Chinese restaurant on the Boulevard Saint-Germain, and in between two bowls of fried noodles, he pulled a piece of paper out of his pocket and showed me this thing that he’d been working on by hand with his team. I told him to eat up and we jumped into the car and went straight to Asnières. We gathered together the designers we have there, and in just a few days he’d launched the programme. We knew that he would bring a sense of modernity to the fashion, but he also brought it to the leather goods. With the patent leather, he hadn’t just flirted with the periphery of Louis Vuitton, he’d gone straight to the heart of the company, and totally spontaneously.

Have there been moments when you’ve not agreed with his creative choices?

To be honest, I think it goes beyond any one particular collection. Sometimes with Marc the difficulty lies in his own great pendulum movement, where from one day to the next he will go back and forth between ideas and impulses. That isn’t easy to keep up with, for both the customers and for the house itself. But, you know, he is a genius, so…

These days creatives need to be more business savvy and businessmen need to be more sensitive to creativity. Discuss.

I think it’s important for creative people to be interested in what works and what doesn’t, beyond the turnover figures. Ultimately, we don’t do fashion just for our own satisfaction, we do it to please the customer. Being indifferent to commercial success shows a sort of autism, but at the same time, I don’t expect designers to read pages and pages of company reports and annual figures. But, you know, everything in good measure.

When things don’t go as planned, do the suits automatically tell the creatives to wise up?

As the manager you have to convey to the creatives how the market is reacting to their ideas. Good or bad. That’s not to say bad sales are solely the result of bad creative decisions. Things might fail because the pricing was unrealistic or there was a problem with the product quality, or maybe the quality was perfect, but it was delivered three weeks late. To do this, you need to show great intellectual honesty; I think that even if you’re not creatively minded, you need to have a creative sensibility, one that allows you to translate the creative into the business and vice versa. But that shouldn’t be confused with actual creative decisions, because if the manager starts thinking of himself as creative, then it’s the beginning of the end!

Did you have this kind of conversation with Marc Jacobs?

For me it’s more on a macro level. It’s the same thing with the architect who is designing your stores: the space could be sublime, but if the chairs aren’t comfortable then customers won’t sit on them for long enough to buy the shoes. This isn’t simply a question of the manager saying, ‘I like it or I don’t like it.’ When we talk about the management and the capacity for distinction, we’re not judging things based on personal taste. We need to have complete confidence in the creative people, whether it’s an architect or a designer. If not, you need to replace them.

It’s often said that your greatest skill as a manager is human management; the fact that everyone at Vuitton both respected and liked you. Is that an inherent talent or is it something that you recognise as a strategy as being just as important as the product?

I think the principal role of the company CEO – as expected by both staff and shareholder – is to propel the business in the right direction and generate the means in order to do so. This obviously includes human means: selecting the right people and providing them with objectives in the clearest and most efficient way possible. As a CEO, you ultimately get judged on your vision and your effectiveness. How your company can survive, how it can grow. But if on top of that you have genuine empathy for the staff, for culture and for craft, then you add that extra bit of energy to a company’s momentum. If you add empathy to a false strategy, it will require a lot more energy, and you’ll probably end up taking the company over the edge.

Can you really be a friendly boss?

Let’s be straight here: it’s better to have a difficult boss with a clear vision than a boss who’s pals with everyone but leads the company to ruin. But I think what the people working in the stores and the ateliers remember are those little extra gestures, a phone call, or a note.

And as the director did you feel fundamentally responsible for your employees?

Of course. That’s 18,000 people. Having always gone to the stores and ateliers, I do know a lot of them; out of the 18,000, perhaps 90% of them have seen me in the flesh.

Can we talk a bit more about the mechanics of managing a company with 18,000 employees?

My job has always been fuelled over the long term by two things: a demanding majority shareholder and a long-term vision. We have the parallel situation of having the company on the stock exchange – so you have to deliver results – while at the same time having a majority shareholder. That’s a very important point. Plus, we’ve never had that cult of the quarterly review; we’re more concerned with what the group will be in 10 years’ time.

What’s the biggest fear with becoming such a big operation?

All organisations that expand have a tendency to become more complex. We open in new countries, we enter new territories, employ more people… so there are more layers of management. The real question in management is how to keep things simple while they become more complex.

How do you delegate while maintaining control?

You have to keep an eye on the macro structure… When there was no prêt-à- porter or footwear, it was a totally different organisation. When we didn’t have the 22 other countries in which we’ve opened over the years, it was much easier to manage geographically. You don’t have the same security problems with a 200m2 shop as you do with one that’s 2000m2 and stocks fine jewellery. But it’s important to resist simplifying elsewhere because things can end up backfiring.

‘It’s 24/7, almost like a religion. It can be midnight and I’m thinking, ‘Where in the world is there a store open right now? I’ll give them a ring.”

Has there been an era or a year when you clearly remember entering into such a complexity?

In 1998 with the beginning of the prêt- à-porter and the catwalk show. There was certainly a sense of there being a ‘before’ and ‘after’ – that the company would never be the same again.

How do you define the difference between fashion and luxury? Are the two things fused at Vuitton?

I think that you can have fashion with- out luxury. Look at Zara, for example. Fast retailing gives the consumer fashion trends in a setting where luxury doesn’t exist. Alternatively, you can have luxury without fashion: Graff diamonds are the height of luxury, but it isn’t fashion. If you succeed at fusing the two then you’ve attained something magical – and very powerful.

What makes the fashion and luxury worlds different to other sectors, such as smartphones, computers and so on, in terms of business and strategy?

Luxury is something that offers extra emotional resonance because it should stir the feeling of being part of something genuinely magic. This magic could mean being part of the history of the brand, or being part of the extraordinary savoir-faire which is palpable, or the creative process which is much stronger than in other sectors.

What distinguishes Marc Jacobs’ collections for Vuitton from those in what you refer to as the ‘fast retailing’ sector of the industry?

Well the fashion concepts that Marc uses to create the collections are the same trends used by the fast retailers three months later, but the emotion is the distinction. I think the luxury indus- try provides the customer with further layers of emotion. One of the successes of a brand like Apple has been to create objects that correspond to the consumer’s desire to listen to music, to communicate while travelling and so on… They’ve created objects that bring this extra emotion through their very function. So in some ways that’s a luxury value. But the ephemeral nature of technology brings a negative side too, where in six months’ time it’s worthless. A true luxury object is something you want to use two years later, 10 years later, a generation later. Then there are the brands where you find an extraordinary aptitude for creation, yet they aren’t creating luxury items. Apple, with Steve Jobs, was a good example of that…

Did you know him personally?

Yes.

What was it like meeting someone equally successful but in a totally different sector?

It was fascinating talking management with him. I think he had great respect for what we did here, and we certainly had a great deal of respect for what he did too. We also collaborated together: Steve would send us their product shapes and forms before they were launched so we could make things like iPad cases before anyone else.

In the specific fashion and luxury sector which other companies do you rec- ognise as having been as successful as Louis Vuitton?

[pauses] It’s difficult to say. Someone who really impressed me was Jean-Louis Dumas. But Hermès is not exactly the same without him.

Does managing a company like Louis Vuitton become an obsession? Do you find yourself checking emails in the evenings, during the weekend?

I think it has to be an obsession. You think about it 24/7, almost like a religion. But that doesn’t mean I’m checking my emails every 10 minutes. And in 42 years of professional life, I’ve never worked in planes either. The best ideas come in these in-between moments, like when you’re driving.

Do you experience that same thing as creative people when you wake up at four in the morning with an idea?

Constantly. At midnight, at two in the morning, all the time! There are always ideas running around. It can be midnight, and I’m thinking, ‘Okay, so where in the world is there a store open right now? I’ll give them a ring.’ You can’t avoid the overlapping of your private life and your professional life with a job like this. You meet so many people around the world, and when they come to Paris, you inevitably have to socialise with them. It’s an amazing opening onto the world, but it does take a toll on your private life.

Are you one of these CEOs or politicians you hear about that only needs four hours sleep a night?

Well, I sleep for four or five hours a night, on average.

Having travelled so much, what’s your secret for dealing with jet lag?

No secrets, but when you’re someone who doesn’t need that much sleep you can grab your four hours here or there and it doesn’t matter.

Have there been times when you’ve experienced great pressure and stress?

It’s inevitable. But there are different types of stress. There are those times during fashion week when you’ve got all the department stores, the editors, the commercial teams in town and every- one wants to see you. And there are other times, like when the Gulf War began in 1991, and we had to make decisions about the coming days. Or when the tsunami hit Japan, we were all hanging on the telephone to find out if our teams were ok; we had to work out what decisions needed to be made and whether or not we should evacuate Tokyo.

Beyond the satisfaction of generating annual growth, did you feel that you had to make Bernard Arnault happy or prove yourself to him? Was that an important motivation for you?

Well, it was the condition for staying! [Laughs]… I think there’s a pride in bringing about results, not just personal pride. Every time we’ve presented a budget and have made more than we thought, it’s a great feeling. It’s very satisfying to beat your own forecast.

‘I’d liken having to leave my post as CEO to when my children left home. You know one day it’s going to happen, but when it does it still affects you.’

As the CEO of Vuitton within the LVMH group, was there a rivalry – healthy or otherwise – between you and, say, Sidney Toledano at Dior or Michael Burke when he was at Fendi?

In all groups with multiple brands working within the same market, there is a degree of emulation. With a group like this, over the past 20 years there have been a few people that have come and gone, but generally speaking, most people consider any so-called rivalry to be a healthy thing. You’re happy if your brand has performed better than others, but you always try to prioritise working together.

What was your greatest moment of pride during your tenure as President at Vuitton?

I think it has to be my vision for China and having opened there in 1992.

Was it instinct or was it based on research and fact?

It was the result of a very long discussion with a French politician called Jean-Francois Deniau, who was an excellent connoisseur of China. He convinced me from 1991 onwards that the modernisation and movement of Asia was under way.

And yet there was risk involved.

It was obvious that the once most powerful nation several centuries ago, would once again wake up. Jean-Francois Deniau convinced me of when to go in. When we were in China in 1990, 1991, 1992, you could only sense the transformation on the surface, but every six months we returned we saw things change. The economy was booming.

As someone who has been travelling to China for 30 years, what do you know now that you didn’t know when you first started going there?

The historical vision that China has of itself as a superpower. It was once the centre of the world, and today it wants to re-establish its place. Put like that it sounds very simplistic, but it explains a lot about their behaviour and attitudes, in both business and social contexts. What I’m trying to say is that China was humiliated by the West. Faced with these historical humiliations there are two attitudes a nation can adopt: I’m going to hide, or I’m going to overcome this. There have been moments in the past which were extremely difficult for the Chinese, but I think their mix of desire and political pragmatism is helping them re-establish their place in the world.

Do you think that the good relationship France currently has with China can be maintained?

Yes, for two reasons. China and France are both countries with a very old culture. That creates a mutual respect. And because de Gaulle was the first to recognise the People’s Republic of China, 50 years on there is still this goodwill. Ultimately, the Chinese are a very pragmatic nation, and that’s why they won’t necessarily buy a more expensive TGV train, or they won’t change human rights overnight, as long as it suits them. But emotionally, the Chinese have an affinity with people who like eating. They have a taste for refined cooking

Do you think that with China you’ve created a monster? Could China one day establish a company like Louis Vuitton but on a far greater scale?

I think we will witness attempts to create luxury brands that belong to other cultures. How many will emerge is difficult to say.

Turnover has been increasing year on year, but you must have thought that it will level off at some point, that the luxury business will reach its summit?

To be honest, no. There can be moments when it slows down, but these are more linked to currency and the state of the euro than economic conditions. But in the long term, I remain convinced that the thirst for luxury goods will continue to increase. The challenge is how to manage this growth; that’s the great paradox of luxury. How do you grow and at the same time maintain this sense of soul and exclusivity, with high quality products and a service that is increasingly sophisticated? It cannot happen if you expand too quickly.

As someone who’s created incredible global success with huge turnovers, you must be contacted 15 times a week by head-hunters looking to recruit you.

[Laughs] Well, when you manage the most beautiful company in the world…

Having been CEO, of ‘the most beautiful company in the world’, is it some- thing that you deeply miss today?

Yes, of course I miss it; I’d be lying if I said I didn’t. But life goes on. I had time to get used to it, I had a year to train my successor. It wasn’t like I just upped and left. I was mentally ready for it to end one day. I guess I’d liken it to when my children left home: you know, one day it’s going to happen, but when it does it still affects you. Similarly, when you run a business you always know that one day you will have to leave.

Let’s talk a bit about your new role as Vice-President of the Fondation d’Entreprise Louis Vuitton pour la Création…

The Foundation is a project that Bernard Arnault has carried within him for a long time. We’ve been talking about it for more than 10 years. He met Frank Gehry and was deeply impressed.

Is there an official date for the inauguration?

We don’t have a fixed date, but it should be around spring/summer 2014.

And what do think the future holds for Louis Vuitton?

It all depends on the people who are working here.

What’s your advice for current CEO Michael Burke?

[Laughs] Hold on for 23 years!