If anyone can change the rules of fashion, it’s Nicolas Ghesquière.

By Jonathan Wingfield

Photographs by Juergen Teller

If anyone can change the rules of fashion, it’s Nicolas Ghesquière.

Part One

Saturday, December 16th, 2012

Hôtel Montalembert, Paris

It’s been just over a month since the shock news of Nicolas Ghesquière’s departure from Balenciaga, and mere days since Alexander Wang was announced as his replacement. Other than a short and sobre press statement from PPR, there has been no explanation, no reasoning and, crucially, not a word from Ghesquière himself.

All of which makes the sight of the designer and his closest collaborator, stylist Marie-Amélie Sauvé, happily tucking into club sandwiches and Diet Cokes all the more surreal. Ghesquière has decided now is as good a time as any to open up about why he and Balenciaga are no longer, what he thinks about the current state of the industry, and what the devil he might be getting up to in the future.

It’s been mutually decided that rather than pinning him into a corner with a dictaphone and a list of loaded questions, the opportunity to discuss recent events and other subjects should take the form of just that, a discussion. It’s not been decided if said discussion will last the time it takes to finish lunch or if it will develop into something long- er and perhaps more significant, but it’s agreed that now is the time to press PLAY.

When journalists rush backstage to speak with designers, they always start with that eternally banal question, ‘What was your inspiration?’ So, let’s start by discussing inspiration. What is it? How do you channel it? How is it changing?

Marie-Amélie Sauvé: Without sounding negative, I find today’s generation of 15, 18, 20-year-olds take their inspiration too literally. We’re living in a world of plagiarism. It’s scary because without pure creation, we’re no longer adding to history.

Nicolas Ghesquière: I’m often most inspired by things beyond the immediate world of fashion. It’s broader cultural or social movements that have influenced looks or identities I’ve created. These days I sense that people don’t dig particularly deep; inspiration rarely goes beyond borrowing what’s happened in the past and rarely with- out adding any new layers of context. By that I mean the culture of fashion has lost some of its depth. Maybe it’s just symptomatic of today’s society and the culture of social networking, where people project themselves via their references and their ‘likes’. Which is fine, but it’s lacking in fundamental values.

Do ideas come easily to you?

NG: I find it’s a dialogue between what I am looking for and what I’m instinctively longing for. When I find that mix, it generally manifests in the things I want to express. Sometimes there are very precise ideas that lead me into research- ing particular themes, but usually once I start looking, other things will come up and that’s when you move into very interesting areas.

Why are we, as Marie-Amélie says, living in a world of plagiarism?

NG: How I see it, fashion has entered the realm of pop culture, alongside television and music. It’s never been so fashionable to like fashion as right now. There was a time not so long ago when the fashion landscape was inhabited by a few marginal people and a few business types; these days, everyone has to be part of it. I’m all for a certain level of democratisation, sure, but right now things are spiralling out of control and heading downwards.

As a designer, how do you avoid being taken downwards with the forces of democratisation?

NG: There is going to be a reaction against the status quo, there always is, certainly in fashion. And so you use this reaction to rise above mediocrity and distinguish yourself. It’s the only way. The system has become so totally saturated, but there is nothing better than a saturated system for reinventing your- self and finding new ways of operating.

MAS: By it’s very nature, fashion operates in cycles, and we’ve already seen this type of reaction before.

NG: Yes, the emergence in the 1980s of the Japanese designers, as well as Gaultier, Montana, and the others here in Paris, was a reaction at the time against haute couture. I remember all the pages in Vogue dedicated to the couturiers’ ready-to-wear lines which had to be photographed, and then suddenly, boom, a whole new system which literally overnight rendered the status quo obsolete.

‘Fashion has entered the realm of pop culture, alongside television and music. It’s never been so fashionable to like fashion as right now.’

MAS: Today everything is mixed up and that’s the problem. I mean is it a lack of knowledge? How come every- thing is all mixed up now? The words fashion and luxury have become indistinguishable: luxury means fashion, and fashion means luxury.

NG: Exactly, yes that’s totally it.

MAS: I don’t see how some of the fast retail brands are going to have a long shelf life. Look at what’s emerging, but also what’s dying just as quickly. Brands are created but they never go anywhere, there’s no long-term vision.

NG: Fast retail brands get their inspiration from opinion leaders - those whose role it is to engage in research, to innovate, to show major direction. Once there are less and less opinion leaders the market will become much less competitive, even amongst themselves.

But what will the fast retail brands do with all the money they’ve quickly accumulated?

NG: Someone said something interesting to me recently: ‘The next classic luxury group will be H&M or Zara.’ It might well be the case. Beyond the collaborations they do at the moment, they will actually employ big designers for the long term. Basically, if they know there’s nowhere left for them to go in their current sector, they might end up stepping up into the luxury domain.

MAS: They clearly want to be considered high fashion; you can see that in the way they’re adopting the same production values as high fashion brands.

NG: But it is so much harder to climb than to fall. That’s where the justice lies in this industry. There are still certain opinion leaders and executives who recognise the need for creativity in the business of a brand. If a brand takes real care of the way things are done, made, advertised, and distributed, then its value has the potential to go up. But so few brands really want to put the effort in because it distracts from making quick profit.

Talking of H&M, had you and Balenciaga been approached by them to collaborate?

NG: Several times.

Were you ever tempted to do it?

NG: No, no, never. I didn’t think it was a good idea strategically for Balencia- ga. I don’t think what they do and what a house like Balenciaga does is the same profession. That’s not to say I don’t find what they do interesting; I think there have been some excellent collaborations. But it all comes down to this discussion about accessibility and exclusivity. What do you give? What don’t you give?

Where does their strength lie?

NG: Well, the resources are amazing. Everyone in luxury is fascinated by the process and the rapidity of these monsters. But at the same time they eliminate the creative phase. Production has eclipsed creativity.

And how do you feel about these fast retail brands taking your Balenciaga designs and repackaging them to the masses?

NG: I realised my success when I saw people recreating looks that we’d done in their own way in the street, with what they had. Not necessarily with clothes by me. When it’s in the street, I really like that. When a friends tell me, ‘It’s mad, I’m seeing all these girls looking like Balenciaga; not necessarily in Balenciaga, but dressing like it,’ that is fine.

MAS: Because the message has got through to the wider world.

NG: Yes, that’s where you feel the influence you’ve had, and that doesn’t bother me at all. I’ve always taken that as a compliment. When there’s a 20 or 25 year age difference, it’s a compliment. But in other cases, it’s done by professionals who are 5, 8 or 10 years younger than me, and people say, ‘Well, it’s normal. These designers have grown up watching you, you’ve been a model to them. It’s worked for you, and they want to do the same thing.’ That bothers me ever so slightly.

Isn’t imitation the greatest form of flattery?

NG: Well, people in the press and so on have been quite tough with me in the past because I’m always searching for new ideas. I’ve occasionally been seriously criticised, hurt even, because when you take risks you can get treated badly. But then two years later, or even a season later, the entire collection is copied in America, or somewhere where people are a bit more indulgent, and I find that strange. I’m here to evolve and hopefully innovate; that’s my role as a designer: to move forward, to take risks, and generate commercial incentives. Then, paradoxically, people turn a blind eye to the plagiarism.

‘Everyone in luxury is fascinated by the speed of the H&Ms and Zaras. But they’ve eliminated the creative phase. Production has eclipsed creativity.’

Do people tell you about specific examples of plagiarism, or do you see them yourself?

NG: I’ve seen lots of things myself. Then Mimi [Marie-Amélie] always tells me about things she’s seen. It doesn’t depress me, it just seems to have become so normal. Almost like, ‘Oh, he’s the opinion leader, it’s his role to be copied.’ Great, but this remains an industry that is based on commerce. It’s not like being an artist in a gallery. And so it does feel a bit unfair.

How does it make you feel, knowing that there are girls all over the world wearing pieces that are direct copies of your collections, without knowing who you are, without knowing the savoir faire and the hours of work that have gone in to get make that design what it is?

NG: It makes me feel a number of things. When it’s mass distributors - like Zara, which is owned by the third richest man in the world - I tend to think that I got involved with the wrong businessmen! I’m joking of course, but when it’s distribution on that scale, it’s about successful business and nothing else; their role is to make fashion more accessible for the sake of commerce and nothing else. When it’s a luxury house or a designer doing it, I find it far more mediocre – that’s my word of the day.

Can we talk about the rapport between business and creativity that lies at the core of this industry.

NG: Today, I find that everyone I meet always talks about business before desire and creative impulse. There are some really good ideas, but business has become the priority over a good idea. I mean, fashion’s profitability and prestige have become much more reliable than many other activities. You know, you feel better if you own a luxury group than a steel group.

Can you identify a moment when the business element infiltrated fashion and corrupted it?

NG: I’ll use Tom Ford and the Gucci Group as an example because he was a creative power even though he also had a sense of business. Although Tom wasn’t the most conceptual of creatives, he did have a creative viewpoint which drove a house and even drove an entire group. There’s no doubt that the fall of Tom Ford from the Gucci Group brought about the end for creative directors like Tom, but also for designers in general. From that point onwards, the control has been in the hands of the corporate side of this industry.

What were your first conversations with Tom Ford about?

NG: I’d met him once before in a restaurant; we shook hands, and he said some very nice things about my work. Then one day he rang; I basically thought someone was joking: ‘Yeah yeah, it’s Tom Ford on the phone.’ But it was him, and told me he wanted us to meet up. Around that time, I’d had quite a lot of proposals – from other houses, from all of the groups, from investors interested in backing my own thing… But Tom was the only one to actually ask, ‘What do you want to do?’

Do you think what Tom Ford did at Gucci changed your personal view of the industry?

NG: Yes, without a doubt. Because suddenly the business side of fashion was no longer embarrassing. Tom’s a total fashion fanatic, but he embraced the business side as much as the seasons of fashion. Thanks to the culture that he and Domenico [de Sole] established, we were suddenly free of any psychological complexes; there was a business, and it operated alongside creativity. Who else did that? Giorgio Armani maybe, but not in the same way. Chanel has never been like that either. Karl is without a doubt the most inventive artistic director, but there really was a before and an after Tom Ford. Tom officialised the status of artistic director of a house.

And Domenico de Sole?

NG: Domenico’s level of comprehension is unique: his vision, right from the start, was incredibly sensitive to creative people. It was so important for him that a house had to be constructed around the creative energy whilst being a good business.

‘Plagiarism doesn’t depress me, it just seems to have become so normal. It’s like, “Oh, he’s the opinion leader, it’s his role to be copied.”’

Would you say this approach was unprecedented?

NG: Yes, I mean there were business models that involved a partnerships like Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé, but the partnership between Tom and Domenico was totally equal. This is a business- man who would empower creatives, who’d say things like, ‘Don’t be scared to do it like this.’ Today I will have the same level of expectation with my future partners as I had with Domenico back then. Dom-Tom, they were the precursors of a model, for sure.

Do you remember early conversations with Domenico de Sole?

NG: I remember going to London secretly to talk to Domenico, and I remember signing the contract at night because it was all top secret. There were lots of meetings, but there was also such freedom; they really did try and adapt things so that the Balenciaga would correspond to what I wanted. They never said, ‘It has to be like this and nothing else.’

And what about when they left the very group they had formed?

NG: I found out about it at the same time as everyone else, and to be honest I did feel abandoned. I told them so, too. Tom said, ‘No, it’s going to be alright.’ Domenico told me he was sorry but that he had no choice. I think we all felt abandoned; we’d all joined the group for them, and what were we going to do now?

You said before that Tom Ford made business seem less embarrassing, more tangible. Did he ever offer you specific creative advice?

NG: I had conversations with Tom where he told me what he liked in my work. He’d say, ‘Look, when you do this, it really works.’ It was a delicate way of directing me. It all happened very naturally though because I had no hang-ups, and I wanted it to go well and almost make them happy. You were in a winning team, each with our own skill.

Would you talk with Stella McCartney and Lee McQueen about all this?

NG: Not so much with Lee because I didn’t know him very well, sadly. But with Stella yes, we get on well. And do you think she felt as enthusiastic as you at the time? I can’t say anything on her behalf, but there’s no doubt she came on board for the same reasons as me. Stella has always had her own point of view and her own convictions. There was definitely complicity between us and no sense of competition. Things were well established, and everyone had their own vision; it was a complimentary group of houses, which maybe wasn’t the case when you had, say, Helmut Lang and Jil Sander at the Prada Group.

Do you think the fact that designers now have less of a complex and that there are such high commercial stakes these days has had a negative impact?

NG: Yes. Of course. The more we sell, the harder it is to convince people that they are buying something exclusive. You inevitably have to lean towards a com- mon denominator: a sign of recognition while remaining an opinion leader and having an exclusive savoir faire, a craftsmanship, and a semi-industrial fabrication, and those elements are difficult to combine, for sure. We are definitely at a crossroads.

Part Two

Saturday, January 5th, 2013

Hôtel Montalembert, Paris

Ghesquière and Sauvé, having approved the idea of a second ‘session’, propose a same-time-same-place in the new year. Since our last rendezvous, rumours continue to circulate as to why Ghesquière left Balenciaga, the payout he got on leaving, and what he was going to do next. Having both just returned from sunny climes, it is with healthy complexion that they order a new round

of club sandwiches and prepare themselves for ‘the second installment’.

At what point into the job at Balenciaga did you realise you needed to wise up to the business side of the brand?

NG: Straight away. It’s part of being a creative because the vision you have is going to end up in the boutique. It actually makes me smile today when I think about it because I had to invent the idea of being commercial at Balenciaga. Right from the start I wanted it to be commercial, but the first group who owned it didn’t have the first notion of commerce; there was no production team. There was nothing.

What was your vision for the brand?

NG: For me, Balenciaga has a history that is just as important as that of Chanel, even if it’s a lesser known name. It had the modernity, it was contemporary, and I’ve always positioned it as a little Chanel or Prada.

‘Being wise to business is all part of being a creative in fashion because the vision you have is going to end up in a store.’

But what makes Chanel and Prada bigger structures?

MAS: The people that surround the designers. Miuccia Prada has an extraordinary partner, which Nicolas never had. You can’t do everything on your own.

NG: And I was doing everything by myself.

So without the right people, building something as big as a Chanel or Prada is unimaginable?

NG: I don’t know if it’s impossible, maybe the system will change, but what’s clear is that those brands, as Marie-Amélie says, have family and partners surrounding them, and they have creative carte blanche. Prada, for example, has made this model where you can be a business and an opinion leader at the same time, which is totally admirable. It’s the same thing at Chanel. Sadly, I never had that. I never had a partner, and I ended up feeling too alone. I had a marvellous studio and design team who were close to me, but it started becoming a bureaucracy and gradually became more corporate, until it was no longer even linked to fashion. In the end, it felt as though they just wanted to be like any other house.

You’re saying this spanned from a lack of dialogue?

NG: From the fact that there was no one helping me on the business side, for example.

Can you give me an example?

NG: They wanted to open up a load of stores but in really mediocre spaces, where people didn’t know the brand. It was a strategy that I just couldn’t relate to. I found this garage space on Faubourg-Saint-Honoré; I got in contact with the real estate guy who’s a friend of a friend, and we started talking… And when I went back to them the reaction was, ‘Oh no no, no, not Faubourg- Saint-Honoré, are you sure?’ And I said yes really, the architecture is amazing, it’s not a classic shop. Oh really, really… then six months went by, six long months of negotiations… it was just so frustrating. Everything was like that.

And the conversations, like that one about the store, who would you have them with?

NG: I’d rather not say. There wasn’t really any direction. I think with Karl and Miuccia, you can feel that it’s the creative people who have the power.

MAS: It was at this point we kind of hit a road block.

NG: And it was around that time that I heard people saying, ‘Your style is Balenciaga now, it’s not your style anymore, it’s Balenciaga’s style.’ That’s what I mean by the dehumanisation. Everything became an asset for the brand, trying to make it ever more corporate – it was all about branding. I don’t have any- thing against that; actually, the thing that I’m most proud of is that it’s become a big financial entity and will continue to exist. But I began to feel as though I was being sucked dry, like they wanted to steal my identity while trying to homogenise things. It just wasn’t fulfilling anymore.

When was the first time you felt your ambitions for the house were no longer compatible with your partners?

NG: It was all the time, but especially over the last two or three years it became one frustration after another. It was really that lack of culture which bothered me in the end. The strongest pieces that we made for the catwalk got ignored by the business people. They forgot that in order to get to that easily sellable biker jacket, it had to go via a technically mastered piece that had been shown on the catwalk. I started to become unhappy when I realised that there was no esteem, interest, or recognition for the research that I did; they only cared about what the merchandisable result would look like. This accelerated desire meant they ignored the fact that all the pieces that remain the most popular today are from collections we made ten years ago. They have become classics and will carry on being so.

MAS: Although the catwalk was extremely rich in ideas and products, there was no follow-up merchandising. With just one jacket you could have triggered whole commercial strategies.

NG: It’s what we wanted to do, but we couldn’t do everything. I was switching between the designs for the catwalk and the merchandisable pieces – I was Mr Merchandiser. Then I had carte blanche to go back to being creative, and then there were the capsule collections, the ‘Made in China’, the trousers for less than 200 euros. And that’s what my days were like.

MAS: There was no one to really develop the brand. It could have become the size of Prada! On one hand, you had the ideas people and on the other the business people, and you could feel that there was no fluidity between the two.

‘There are people I’ve worked with who say they love fashion yet they’ve never actually grasped that this isn’t a yoghurt or a piece of furniture.’

NG: Undoubtedly, but you need the right filters; you need competent people. There was never a merchandiser at Balenciaga, which I regret terribly.

Did you never go to the top of the group and ask for the support you needed?

NG: Yes, endlessly!

MAS: But they didn’t understand.

NG: More than anything else, you need people who understand fashion. There are people I’ve worked with who have never understood how fashion works. They keep saying they love fashion, yet they’ve never actually grasped that this isn’t yoghurt or a piece of furniture - products in the purest sense of the term. They just don’t understand the process at all, and so now they’re transforming it into something much more reproducible and flat.

What’s the alternative to this?

NG: You need to have the right people around you: people who adore the luxury domain. There has to be a vision, but there also has to be a partner, a duo, someone to help you carry it. I haven’t lost hope!

At the time when you were starting to feel that frustration, did you talk to any other designers who were in the same situation?

NG: Yes. What’s interesting is how my split from Balenciaga has encouraged people to get in touch with me, and they’ve said, ‘Me too, I’m in the same situation. I want to leave too.’ There are others, but my situation at Balenciaga was very particular.

What’s your feeling about luxury groups today?

NG: I have nothing against groups. They can be very good because it can provide a brand with the much need- ed resources it needs, and there can be great synergies, so I am very pro-group. However, I also feel that groups, even those that know what luxury is, are questioning the formulas, they can see that things are sliding. They know there are very cheap clothes being sold today, they’re questioning the very fundamental elements of the process.

Can fashion today exist outside of the big groups? Or have those groups changed the way fashion is made?

NG: I don’t think I’m really able to answer that because certain groups are transforming. Certain groups are looking for new models themselves and they are conscious of their position in the market; they know that they will have to renew that positioning. I don’t think that it will be easy for them to detach themselves from certain business mod- els once again, but there is definitely a spirit of research with some of them. I think what’s going to be interesting is the punk effect and what that will provoke; existing outside the groups should be impossible, but someone will arrive and prove us wrong. That’s very exciting. There will be a new means of consuming. It might mean the mass distributors, which are already big groups and are focused on certain brands, might want to start focusing on luxury.

You mentioned before your admiration for the structure that Prada have. What other structures have impressed you?

NG: Azzedine is a model to me because he’s the one who has best protected himself, he has maintained continuity while making radical choices with zero compromise. But at the same time he really has a signature and an identity which is totally recognisable. It’s a great business, too, which certainly shouldn’t be forgotten. It’s always been managed very well, very articulately. Even his business model is made-to-measure, and that’s amazing.

Any others?

NG: There’s Rei Kawakubo. Not necessarily in the way she presents her collections - which also happens to be extraordinary - but the way she has built a business, especially in Japan, with the quality of the boutiques and the merchandising in them. No one really talks about Comme des Garçons merchandising, but it is amazing.

And what is it about the rapport between Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli that impresses you?

NG: I just think they’re the most successful in terms of the quality of distribution and merchandising – it’s pretty extraordinary. While they’ve succeeded in developing a successful commercial empire, every season Miuccia Prada continues to unveil a totally radical viewpoint, she never holds back.

In spite of the increasingly stifling conditions you felt you were operating in, were you nonetheless scared by the prospect of leaving Balenciaga?

NG: I just said to myself, ‘Okay, well you have to leave, you have to cut the cord.’ But I didn’t say anything to anyone, apart from to a few very close people, because, you know, I’ve become pretty good at standing on my own two feet.

‘My split from Balenciaga has encouraged people to get in touch with me, and they’ve said, “I’m in the same situation. I want to leave too.”’

Once you’d decided enough was enough and you made your intentions clear, were the directors surprised that you wanted to leave?

NG: Yes. I think so, because I’d shown my ambitions for the house. There’d been lots of discussions, of course, and there were clearly some differences, but that sort of decision doesn’t just come out of nowhere. I’d been thinking a lot too. I was having trouble sleeping at

one point. [Laughs] But there’s usually something keeping me awake.

How did you go about informing your design team?

NG: That was the hardest and most moving part. I couldn’t say goodbye to everyone. I wanted to do it individually as opposed to as a collective because I felt like farewell drinks was too corporate. I made appointments to say thank you and that I would see them soon. And what most of them said to me was, ‘Oh la la, I want to say thank you because I feel as though I’ve been part of fashion his- tory.’ I felt that was so moving because I’d never thought about it like that.

And how did they find out…

NG: Oh, it was awful, they found out afterwards. It was really badly done, and everyone was in a state of shock. Some people just left straight away. It could have certainly been done with a bit more subtly, with a bit more dignity.

After the announcement, did lots of people in the fashion world contact you?

NG: I didn’t actually see all the reactions straight away because I was in Japan at the time; one of my best friends had taken me on something of a spiritual trip to observe people who make traditional lacquer and obi belts; it was such a privileged environment with tea ceremonies. On the other side of the world, there was this violent announcement being made. When I got back to Paris I saw the press, and with all the commentary going on I actually learnt things about myself; it was quite beautiful in fact. Generally the reaction had been very positive, even on Twitter there were some very satisfactory things being written. Ultimately, I felt okay in the end because it seemed very dignified. I haven’t expressed myself up until now, but I would like to say thank you to everyone, I really am very grateful.

Did you ever think about making a personal announcement?

NG: No, I never wanted to express myself like that. I don’t know how to do that.

What’s the most exciting thing about this period of time for you?

NG: Preparing for the next chapter and having the time to observe what’s going on in the industry. People could have forever associated me with Balenciaga. We saw clearly when the split took place that there was a desire for my name, so I disassociated myself naturally from the house. That could have been a risk. It would have been different if Balenciaga had disassociated itself from me, but people had seen me develop my signature and knew that it might happen. That’s exciting because whatever choice I make, the possibilities are open, and that was confirmed with the freeing of my name from Balenciaga. I’d made so much effort and been such a good obedient kid in associating myself… Now I can imagine a whole new vocabulary. I’m regenerating again, and that’s very exciting because it’s a feeling I haven’t had since I was in my twenties.

Why are you one of the few who has managed to retain a sense of integrity in this domain?

NG: Because I was never scared to fight and speak out – to have an opinion. I was sensitive to the economic climate without being scared of having a strong point of view, and saying that was what should drive the house. I was happy where I was in spite of other offers over the years. I’m very loyal, and I felt as though I had a mission to accomplish.

Do you think that loyalty is a real value in this business?

NG: Yes, because what perverts this job is that we’re constantly rejecting things and expecting them to arrive faster. The faster things arrive, the fast- er you get a result, the more money you make. So you become completely impatient, which has definitely been one of my faults over the years because you’re always on this mission. I’m working my patience now, in this lull.

‘The faster things arrive, the faster you get results, the more money you make. So you become completely impatient, which is one of my faults.’

Today, with a bit of hindsight since the separation from Balenciaga, do you have a favourite collection?

NG: I actually did a little recap recently, and I watched all the videos, one after another, 15 years and 30 shows from the first to the last. It was actually a far easier experience than I thought it was going to be! I enjoyed watching the punks collection again. That was a good collection, and the girls were great: we had Gisele closing it, we had Stella, Amber, Belgian girls, Anne-Catherine, new faces at the beginning. Then there was the one we called ‘The Explorers’ with big parkas and white puffball dresses, Autumn/Winter 2005-2006.

What about the Cristobal Balenciaga collection?

NG: I guess that was really the moment of recognition. I received letters from everyone, from Karl and the Chambre Syndicale, saying welcome, you’ve made it. ‘The Flowers’ was another one which was superb. It was ultra radical with classical music and a carpet of flowers, all in the dark with lots of repetition. And lastly, the one at the office tower last season, I really loved that moment. I actually think that was a determining factor in my decision to leave.

Had you already made up your mind?

NG: I think the seed was germinating. I was already wound up because the powers that be really didn’t understand the need for a show that they felt was so ‘edgy’. We’d found this slightly strange empty office tower, Dominique [Gonzales-Foerster] did the set, and it was sublime. I love the fact that the weather was bad, and there was mist, and we were in this tower, and it was totally cinematic.

What did you typically do the day after a show?

NG: I’ve tried everything: compulsive shopping, immediately going on holi- day… Nothing works, it’s a metaphorical hangover, a meltdown no matter what. In fact what works the best, strangely, is just going back to work.

What will you miss most about Balenciaga?

NG: I will definitely miss the studio and the atelier, but the rest not at all. Quite the opposite in fact. I really do feel as though I am no longer being sucked dry. No one is asking me things endlessly, asking for ideas all the time: what’s next, what’s next, what’s next? So you’ve almost come right back to the origins, and it’s just you and Marie-Amélie again with a small team.

MAS: But it’s good when there aren’t many of you because ideas are shared more easily. It’s more fluid.

NG: And we have to protect ourselves following the experience we’ve had. But I feel a weight off my shoulders now. I’m excited to start building my collage again because I won’t be able to go for long without creating something again soon. Ultimately though, the thing that remains is this beautiful story behind me already. That’s what I like about the celebration of my departure: 15 years, done and dusted. You cannot argue with that. There was a vision.

Part Three

Saturday, January 26th, 2013

Hôtel Montalembert, Paris

Just when you think you’re falling nicely into a routine - Saturday lunchtime, table for three, club sandwiches, and a couple of hours to chat - things take a slight detour. Ghesquière, graciously arrives a little flustered. ‘Please, order some food,’ he politely offers, ‘I’ll only have time for a coffee.’ With under an hour to spare, the studiously prepared questions about the Balenciaga fallout or what on earth he might be up to behind closed (office) doors are put aside. This calls for a change of approach. Rapid-fire question time.

We talked before about the collage that people build up on Facebook, but there was a time when we did that in our bedrooms.

MAS: Yes, we stuck up posters and images.

Do you remember what you stuck up on your walls?

NG: Yes, I drew a lot, so there were loads of my own pictures. I loved that Ken Russell film, The Devils, with Vanessa Redgrave, so I had pictures of the actors, and of course Alien with Sigourney Weaver and other science-fiction images… Plus posters or photos of major icons of the time like Grace Jones. I remember insisting that my parents let me have a completely white bedroom, which they refused because they preferred me to have floral fabric wallpaper. So one day, I covered my walls with white paper. Later on, when I was a teenager, I took all the white sheets I could find in the house and covered my bed, the sofa, the television, everything I had in the bedroom. Everything was white. I remember my mother came in and she was really concerned that there was something wrong with me. [Laughs] But, you know, I just needed that white space, and in the end they let me keep it like that.

‘The day after the show I’ve tried everything: compulsive shopping, going on holiday… Nothing works, it’s a metaphorical hangover.’

When we’re adolescents, there are visual elements in life we’re not really equipped to notice. I mean, there aren’t many 12 year olds who say, ‘Wow, I love that Le Corbusier building!’

NG: Oh, that was me! I loved those aesthetics already. If I saw an image of something I liked, I immediately tore out the page. Buildings, everything – it wasn’t at all limited to fashion. It’s still the same today when I compile images; they can take shape in any number of ways. I had a Polaroid camera when I was younger and used to take pictures of the television.

And buildings?

NG: Yes, derelict factories and old railway stations near my house. Then when you start studying, you discover more architecture: Oscar Niemeyer and so on. I think I’ve always been driven by this sense of curiosity. Fashion was the catalyst, but at one point it could have come from somewhere else.

MAS: Nicolas could have been an artist or made films. For me, he really could have been an architect. NG: I think it’s the mise-en-scène that drew me to fashion. Then there’s the technical side and the construction, and the need to be rigorous and precise, so it makes an ideal ensemble.

How old were you when you had this clear vision of what you wanted to do?

NG: About 11 or 12. It was very early on that I knew I wanted to work in fashion.

And you Marie-Amélie?

MAS: I loved fashion because it was part of my world, but I didn’t say I was going to work in that industry. That came later. NG: But it’s already quite unusual to have liked fashion. MAS: Well, I really loved fashion and clothes, but I hadn’t thought about working in that world. My bedroom walls were plastered with fashion imagery, so of course it was there, but I didn’t allow myself to think about a

career in fashion because I had parents who thought it was… they wanted me to have a serious education.

Aside from the Grace Jones photos, do you remember the first fashion images that you were drawn to?

NG: It started with classic things, photographs in magazines. I was brought up out in the countryside, but my moth- er had Vogue and all the magazines, so that started very early on. I remember one particular copy of Vogue; it was a Gruau Christmas special. The other images I was specifically drawn to were by Irving Penn: the still lifes, the portraits, like the one of Picasso…

Were you ever photographed by Penn?

NG: Yes, in 2006 I think. He shot me wearing a scarf. Every time he came to Paris, he always stayed at a hotel right next to where we are, the Pont Royal.

Did he photograph you in Paris?

NG: No, at his studio in New York. It was quite a big deal. I had to meet him twice beforehand because he didn’t really like photographing people and would generally refuse. He shot very few fashion designers, and he refused certain actresses. It was Anna Wintour who asked him to shoot me, and I think he accepted because he liked my work. He told me that while we were having tea together one afternoon. I think he was quite nostalgic for Paris too, because he would come here with his wife. After the portrait, we did a few other things together: there was a photo of Cate Blanchett dressed as Queen Elizabeth. I did my dress for Elizabeth, and the photo he took is truly sublime. It was so inspiring to witness someone well into his eighties remain as focused as he’d been all his life.

Do you see yourself working in fashion all your life?

NG: Yes, I think so; I can’t imagine not being involved in fashion in any case. I do actually have fantasies of retiring sometimes, so I don’t think I’ll do it forever.

Do you think that fashion is something that you can continue to do when you are old?

NG: Fashion is a playground up until a certain age, and then you absolutely have to find your style. I mean, you can engage in changing fashions and trends for years, but from the moment that a designer finds their signature, it’s often a case of purifying that over time. There’s a Gaultier quote that keeps coming back to me: ‘A young designer has to know that I was once like him, and that one day he will be like me.’ I find it really interesting, not because I’m comparing it to myself, it’s just super interesting. Today there is a race for discovery; there are young talents who arrive completely ready to express themselves and others that lack maturity. Azzedine has always said that a career should start at 40…

‘When I was a teenager, I covered all my bedroom with white sheets. My mother was concerned that there was something wrong with me.’

Do you have creative talents outside fashion?

NG: No, I think it always manifested itself like this, through drawing. What’s the difference between style and fashion? Is that easy to verbalise?

NG: Style can take every form, whether it is instantly recognisable or a style unto itself. Fashion is what will have an immediate impact, be ultra desirable, and seductive in that particular moment. But, you know, when you’re creating something, you don’t say to yourself, ‘Oh, this is going to become a timeless style.’ It’s a subconscious thing.

Could you give me an example of style?

NG: Kubrick, who can make both Barry Lyndon and A Clockwork Orange. He made a conscious decision to explore every cinematic category — historical, futuristic, science fiction… — and yet the atmosphere, the style of any of those films makes it undoubtedly Kubrick. In fashion, there are people like Rei Kawakubo, in a totally radical category, but the imprint is definitely there with that unique combination that is absolutely identifiable. It is the Comme de Garçons style. Azzedine of course, but also Jean-Paul. Issey Miyake too. Helmut Lang, without a doubt; his work is always instantly recognisable.

Can you define your signature?

NG: Ooh, that’s probably the hardest question. I’d say, there’s an interest in experimentation and technique, and I think I already had certain codes and a signature in the construction. But it’s very difficult to say because it’s what makes me – it’s my identity.

When you look back at yourself when you arrived at Balenciaga 15 years ago and Nicolas Ghesquiere today, how do you compare the two?

NG: I was very determined back then, that’s for sure. At the beginning, people would say, ‘Oh, he has a bad temperament,’ and the people who worked around me would explain, ‘No he doesn’t, he just has a lot of character. It’s different!’ People still have this idea of me as complicated and tricky, but I think I’m just determined.

I can’t imagine you could successfully oversee a fashion house if you weren’t.

NG: When I see young designers today arriving at a big house, the advice I would give them is, be driven, be passionate. The whole house is going to be there, and you have to take everyone on your journey.

Today we are bombarded with images, and it’s rare that any one particular image actually lingers. What was the last image that captured your attention?

NG: It’s actually a film from the 1970s with Patrick Dewaere [Série noire] that I saw the other day; it’s totally mad. In eve- ry scene, the radio is playing really loudly in the background, so you can hardly hear anyone speaking. It’s super conceptual, and the styling is just amazing.

How is Patrick Dewaere dressed?

NG: He has a white polo neck under a V-neck jumper and trench coat, boots, and flares. Marie Trintignant is in it too. I can’t stop thinking about it; I can’t help but wonder what fuelled the director into making it…

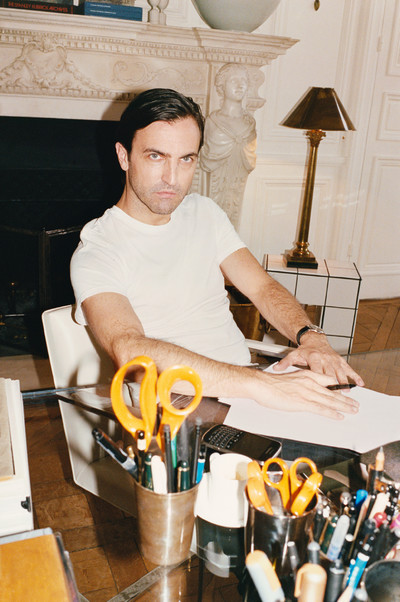

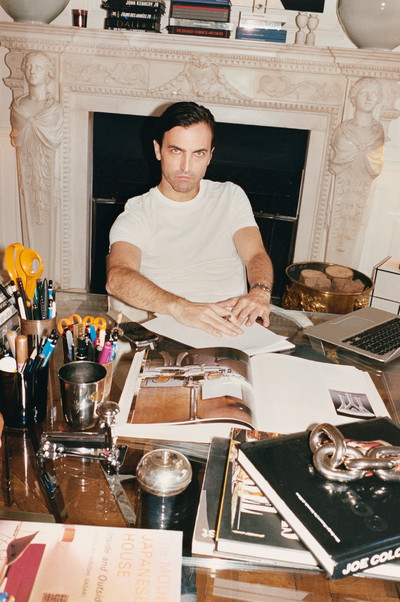

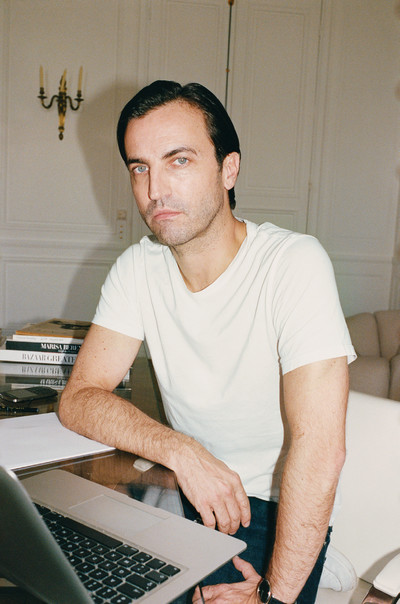

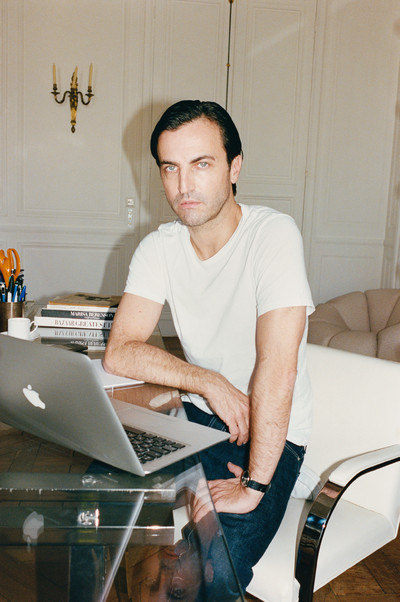

What about the cover image for this magazine? What inspired that?

NG: Until now, I’ve avoided showing pictures of myself at work; we’ve never shown the fittings and no one has ever seen my office. So I thought it would be an interesting thing to reveal at this moment in time when everyone is ask- ing, ‘What is he going to do next?’ I like those images from the 1970s which show Halston or whoever at work, partly because that’s just not really done these days. Most of the time it’s the model or the designer’s ‘official portrait’.

Why is that?

NG: Because designers, or rather, artistic directors don’t draw anymore! I wanted to put myself in that situation. I saw a photo of Antonio Lopez at work with all his brushes and pencils, and it’s inspiring, so the images we made with Juergen show the context of ‘work-in- progress’. It was like a snapshot of the moment: when it comes out there won’t be any concrete work to show anyone this season, but it’s an introduction to what’s coming.

‘Fashion is a playground up until a certain age, but then you absolutely have to find your own signature and your own style.’

Has everything already been done in fashion? Is fashion today a composition of existing elements, or can new things be invented?

NG: I think there will always be new expressions; it’s linked to the individuals involved. It’s like saying the plan- et is well populated, but everyone has a different identity and expression, and will make a little, or big, contribution to evolution.

What is the importance of originality?

NG: There are two things. There’s being conscious of the origin, being able to define its origins. But then originality can also be completely abstract and undefinable. It also means being differ- ent, and that being different is often the result of an inexplicable association. I personally like both aspects.

When you create new things, is there sometimes a big discrepancy between what you set out to achieve and how people interpret what they see?

NG: Yes.

Do you read reviews and think, ‘How strange, that’s not at all what I wanted to say.’

NG: No, that never happens. The truth always comes out in the end. I’ve always discovered things about myself through what’s been written, even if it wasn’t exactly what I wanted to say. I remember Sally Singer wrote me a note after the Sailor collection saying, ‘It was everything I usually hate about the 1980s — black and white, gold buttons, sailors — but this is everything that I adore. It’s new and fresh.’ Quite often, after their initial impression, people think about the collections in a different way and then understand what we were trying to do. People have sometimes misunderstood meaning, but then a year later it’s been, ‘Bravo, we get it.’

How do you react to bad reviews?

NG: There haven’t been that many. Cathy Horyn was particularly tough one time when she wrote that it wasn’t up to the standards of a designer like me. But you know what, she wasn’t wrong. She focused on the mixing-in of street style, and we’d focused on this idea of mix-and-match. Although the looks could have been perceived as street wear, the way in which they were constructed made them the complete opposite. So she wasn’t wrong, maybe she just hadn’t seen the clothes up close. MAS: And it ended up being the collection that was the most copied!

How do you personally quantify the success of a collection?

NG: I think it’s when we’ve innovated. It’s not necessarily linked to commercial success; it’s more about the influence you have on women and the way they dress. It’s not just the women who actually wear your clothes, it’s your inffuence on the way people dress on a far broader level.

Which collection had the most impact on the way women dress?

NG: Without bragging, there are lots of them. It’s what makes up the core of the wardrobe: the masculine cut trousers, the leggings, the different heights of the shoes, the re-tailored blazers…

MAS: The biker jacket.

NG: The tops with the quilted shoulders. A trapeze cut skirt, cut as if you cut it with a pair of scissors.

MAS: The larger volume coats we did.

NG: The Cristobal egg-shape… There are quite a lot of things. It’s like all the elements that come together to create a complete look. In fact, it is a look, which is interesting.

Part Four

Thursday, February 7th, 2013

Nicolas Ghesquière

HQ Quai Voltaire, Paris

Thursday is a work day, and a work day means a rendezvous at Nicolas Ghesquière’s headquarters, a sublime 18th century apartment across the Seine from the Louvre. Parquet floors, marble fireplaces and coffee tables, 1970s and 1980s furniture, a Star Wars stormtrooper helmet, hints of tiled décor from previous Balenciaga shows, Joe Colombo and Pierre Cardin books, and an extraordinary sense of quiet and calm. While a tiny atelier team work silently and studiously in a hidden away office/design studio, Ghesquière (alone, Sauvé is currently abroad) takes a seat and readies himself for Part Four. As the discussion has grown, so has the idea that maybe some other individuals might want to ask Ghesquière a question.

‘I thought it would be interesting to reveal my office at this moment in time when everyone is asking, “Where is he going to work next?”’

Do you already feel distanced from Balenciaga?

NG: Yes, increasingly. Working on something else helps me to naturally detach myself. But of course, there was a mourning period, you don’t forget fifteen years just like that.

Given that everyone associates you through your collections and your silhouettes for Balenciaga, does that now force you to create something radically different, a whole new vocabulary?

NG: I’m pretty situational, so I believe a lot in how you react to and behave in certain situations. There are clearly many things that I’ve done which belong to Balenciaga. But I also know what belongs to me, what I built, and what is coming with me. I have my style, and it will be interpreted differently now. I can’t erase that, it belongs to me.

And this idea of creating a new vocabulary that belongs to you, does it lead you to somewhere completely different?

NG: Yes, because I’ve realised that with Balenciaga, there was the comfort of its history, which was something of a hindrance, as opposed to doing something of my own. I’m very excited about creating my own tools that will allow me to express my own style. I wasn’t ever able to start from scratch before. And I really like that idea, it doesn’t scare me.

Can you talk about your creative ambitions for your new ventures?

NG: I don’t want to sound pretentious and say that I am going to invent an entirely new model of operating in fash- ion, but that’s my ambition. In terms of rhythm, in terms of seasons, in terms of what I offer.

Do you find the way that fashion is presented seasonally to be…

NG: Completely out of sync?

You said it.

NG: I think seasons have no importance anymore because seasons are different all over the world. Fashion has become such a global affair. Shows have traditionally taken place where the clientele predominantly existed, but that idea is just dead now. 4849 What about the quality of the shows themselves?

NG: Fashion week used to be some- thing with a certain degree of quality, but now it resembles the ready-to-wear trade fairs of the 1980s. In New York in particular, it’s been hijacked by all the sponsorship and events which serve only as images to sell things later on; there aren’t even really clothes up on the catwalk.

Have you thought this for a long time, or has it only recently crossed your mind?

NG: I’ve thought this for a few years now, but it’s accelerated a lot in recent seasons. As part of fashion week, you find yourself increasingly questioning the economic stakes at hand; overly radical decisions have become dangerous when the results are so immediate, and this has resulted in a great sense of prudence, whereas the heart of fashion has always been about introducing new methods and taking risks.

Did you ever feel that you were veering more towards commerciality to the detriment of creativity?

NG: No, because it was always intentional. When I wanted to do something commercial, I always said to myself that it would be the very best commercial scenario. I’ve always thrown myself totally into it and found the best ways to make extremely high quality commercial pieces. It was never a compromise, so I never had that kind of dilemma.

If you had to choose between the success of Rei Kawakubo and the success of Giorgio Armani?

NG: Both of them are completely respectable. Stylistically, I won’t hide the fact I feel closer to Rei Kawakubo. I also have a lot of respect for Armani, who I think has succeeded in creating a business model that is extremely faithful to his vision. That is totally respectable; the fashion is something else. He has become an empire on his own, which really is remarkable.

How would you define luxury?

NG: Everything seems to have a luxury stamp. For me there are two important things that define luxury. Firstly, for something to be really luxurious, there has to be genuine quality in the fabrication: the savoir faire, the quality of production and engineering, the way it has been thought out and conceived, the choice of materials. And the sheer time taken to make it – you have to know how to be patient. The other criteria is innovation: something differ- ent and new, something that someone else doesn’t have. That costs a lot. That to me is luxury.

‘Success is not just the women who actually wear your clothes; it’s your influence on the way people dress on a far broader level.’

So innovation is true luxury.

NG: Well, look at something like industrial design. It’s innovative, well made, and well positioned, and doesn’t have to pretend to be luxurious. It’s good enough that it’s been intelligently designed and produced. I find that a lot more interesting than something that is fake luxury.

Who delivers intelligent solutions today?

NG: [Pauses] That’s a good question.

Or are intelligent solutions important in fashion?

NG: Yes, because they reflect the times.

What is the most intelligent solution that you created during your time at Balenciaga?

NG: Ooh la la! I don’t know! [Pauses]… I’m not saying that it was a visionary approach, but I managed to establish a silhouette and keep the identity of that silhouette, which I’d developed with the show and the very upscale propositions, and turn it into something more accessible. And that worked.

I have a question for you from Cindy Sherman: ‘What surprises you when you see your ideas go from drawings to actual wearable designs, and what kinds of compromises are sometimes needed to make that transformation happen?’

NG: I have the impression that once it’s materialised, I have to be surprised myself. If I think it looks like the draw- ing, it’s not necessarily been a success. I design and create something, and then I make it materialise. I constantly question the process of materialisation, the opposite I think to other designers today, because I’m very hands on.

So the materialisation adds value.

NG: Without doubt. It needs to have been transformed and acquired value. If there are obvious references, they need to be erased. If the volume is a bit obscure, then it needs to be mastered.

And what about the compromises linked to this transformation?

NG: Fashion is constant compromise. The game is then about being on form in order to transform compromise into something good, something new. This often means simplifying, and that is generally the hardest thing of all. If you simplify, and it ends up impeccably, and you maintain your identity then that’s brilliant — it’s purity à la Azzedine Alaïa — but sadly that’s rarely possible.

What about the time constraints linked to fashion’s rigid calendar?

NG: That’s the worst thing — having an idea just for a season and not having the time to perfect it. You either have to carry it over or abandon it. That is how fashion works; it has to exist viscerally at exactly that moment in time because moving things to six months later is a real compromise. I did it several times, and it really was an enormous sacrifice. I’d wake up in the night thinking, ‘I’ve got to do it, and it kills me that I cannot do it now; it would have been perfect for this season.’

Is six months later too late?

NG: Well, doing things at the right moment is the essence of fashion. Ear- ly enough to surprise, but not too early that you get ignored, and people only see the idea as an anecdote.

Do your ideas start with a sketch?

NG: Yes, a lot of the time.

Do you draw every day?

NG: Not every day, but I draw a lot, yes. I really like it. It’s like the gym: I’ll stop for a week and then start again; I won’t be any good for a couple of hours, but then it comes back again. I love it. Right now, I’m enjoying drawing more and more because I’m not doing it under the pressure of knowing that anything I draw has to be immediately materialised.

What is it about Cindy Sherman’s work that interests you?

NG: I’m particularly fascinated by the materials she uses that end up making her pictures totally undefinable. You don’t even know what the skin or fabric has been made from; it’s a sort of blurring of photographs, organic matter, colours, and prosthesis that come together to create something entirely new. When I see her work, it makes me want to find those materials. And as a person I like her a lot. She is very beautiful which people don’t always expect because we don’t normally see her as herself; but she really does have charisma and beauty. She has something very special.

‘Doing things at the right moment is the essence of fashion. Early enough to surprise, but not too early that people only see the idea as an anecdote.’

Now to a question from Hans Ulrich Obrist: ‘Nicolas, can you please tell us about your unrealised projects that have been too big to be realised, or maybe too small to be realised, or a project that was censored, or maybe a project that was self-censored, projects that one doesn’t dare to do?’

NG: There are two unrealised film projects with Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster that are close to my heart. One of them is a science-fiction film we’ve wanted to make for years. The other is a documentary: a sort of journey through what we have in common, based on reality. We started writing it last year with the aim of making it, but it’s a project that will take some time.

What is it that interests you in the genre of science fiction?

NG: It’s the contrasts. I’ll give some examples: in Houellebecq’s book The Possibility of an Island, where he goes on this sort of pilgrimage to an organic, nebulous desert, but you’ve no idea where it is. Or in Solaris, it’s not science fiction in a futurist way; it can be a very spiritual, organic science fiction, almost naturalist. There are lots of forms of science fiction that interest me.

Do you have a favourite science fiction film?

NG: Solaris is good because this nebulous thing arrives, and it’s this kind of spatial drift that’s materialised. I adore Stanley Kubrick. I love Ridley Scott – the first Alien is a masterpiece. I found Prometheus quite amazing. I loved 2046. Actually, I’m going to refer back to Dominique; do you remember when she did her installation at the Tate Modern? One of the works in the Turbine Hall was a montage of science fiction film sets, so maybe that’s my favourite science fiction film.

What about designers like Pierre Cardin and Courrèges?

NG: I love them! We’ve talked before about marrying innovation and good execution, and Cardin is the perfect example of that. It was perfectly made, perfectly sewn, it had genuine savoir faire, and at the same time a totally free and expressive vision. The same with Courrèges. And Emmanuel Ungaro too. Their clothes were described as prêt-à-porter, but in reality it was couture. Ungaro and Courrèges both worked for a time at Balenciaga, and you can sense that. Last question for today. In a behind- the-scenes film about a Balenciaga fragrance, Charlotte Gainsbourg says, ‘Nicolas doesn’t give up until he’s happy.’

NG: Yes it’s true.

I wanted to ask if you felt you’d abandoned Balenciaga?

NG: Yes.

And are you happy with the new situation?

NG: Yes, I am very happy. The chance for personal expression is a great way to happiness. For the moment, I’m totally satisfied.

Part Five

Friday, March 29th, 2013

Nicolas Ghesquière HQ

Quai Voltaire, Paris

Over a month has passed since our last meeting, and with the System deadline looming, this is to be the final part of ‘the discussion’ (which will result in almost 12 hours of transcribed copy). In the period since our previous recording, Ghesquière has spent four weeks abroad, wisely skipping out of town the morning the seasonal fashion shows were scheduled to start in an attempt to ‘create some dis- tance’ between himself and the industry that was becoming ever more curious of his movements. He is looking unfeasibly healthy, rested, and tanned after having vacationed in St Barths before spending a fortnight in Los Angeles — visiting Tony Duquette’s Beverly Hills residence, the suspended glass Neutra house that juts out of the Hollywood Hills, and the world’s largest personal collection of fabrics (owned by a cosmetics baron) — the go-to sights for the world’s most sought-after fashion designer.

Meanwhile in Paris, the rumours of the designer’s apparent next move have reached fever pitch. Will he launch his own brand? Will he take charge at a Parisian powerhouse? Moving into one of the Quai Voltaire salons, Ghesquière rolls up his sleeves, plonks himself on the thick rug and for the last time, it’s PLAY.

Since we last saw one another, some other people have sent me questions to ask you. Can we start with Tom Ford?

NG: Yes, great.

Okay, so he says, ‘In my opinion what you did at Balenciaga was brilliant.’

NG: Thank you Tom!

‘How does it feel to leave a house that you single-handedly resurrected and to see yourself replaced by another designer?’

NG: Ah, that’s something Tom and I have in common! I think I see it in the same way as he does: I’m not sad, it’s like having a beautiful old house and being the tenant, and you never actually let yourself own these things.

‘It makes me a bit sad to see that what goes on outside the shows seems to interest people more than what goes on inside.’

What’s your legacy?

NG: I see it as a sort of mission accomplished. They needed someone like me over those last few years to re-establish themselves and to reinstall the interest and prestige the house deserved. I think when I first started, I wanted Balenciaga to one day regain its reputation as an opinion leader in fashion, whilst simultaneously expressing my own signature. I feel like I’ve had this marvellous schooling - having never actually attended fashion school - and at Balenciaga, I was lucky enough to learn on the job. It’s funny that Tom should ask me that question because I think at Gucci he was the entrepreneur of a house that had been pretty much abandoned, and he gave it the dimension it truly deserved.

What are your thoughts abut the future of Balenciaga?

NG: What happens now is no longer my problem. I don’t feel they’re replacing me, and to be honest it doesn’t really interest me that much. So I have no judgement to pass.

Did you see the latest Balenciaga show?

NG: I sort of looked at it, but not much. I’ve seen pieces that have come out, but I haven’t gone looking for it. It’s strange, but I’m just not that curious anymore. I was worried I might be, but I’m not. I’ve turned the page, and now I’ll look at it as I look at the other collections of the season. I’m just not that interested anymore. Nothing belongs to anyone, just to emphasise that again. We only play our part in a relay, especially with a heritage like Balenciaga. I had my time there, and now a new era is beginning.

Do you have any advice to give to your successor?

NG: No, I haven’t, honestly none at all.

Did you miss not doing a show this year?

NG: No, but taking a step back allowed me to see some magnificent collections: the Japanese, as always, are afraid of nothing; these are people who have a firm point of view. Then you see the others who are struggling to keep up… It was quite interesting having a bit of distance and watching this ‘circus’ unfold; you really sense incoherence and confusion with everyone showing all over the place. When you take a step back, that’s when you realise that things do have to change. It gives me even more conviction in that sense.

Did you miss any of the people from the ‘circus’ as it rolled into town without you?

NG: I obviously thought about a lot of people. In fact a lot of people got in touch, and I received lots of text messages saying, ‘We miss you, when are you coming back?’ People were curious and kind; it was humbling. Other designers - like Alber Elbaz, who I adore - sent me messages saying, ‘We’re thinking of you. It’s weird you not being around this season.’ So there was this wave of kindness. But no, I didn’t miss anything.

Is there any cynicism towards the ‘circus’ that comes when you take a step back?

NG: No, because when you’re in the thick of it, you don’t really engage with the ‘circus’. In a way, I was always part of it, but at a distance. I mean, I never went to other shows; I don’t even know what it’s like arriving at a show, or what anyone else’s backstage is like. The distance I’ve recently had has resulted in a bit more reflection, but hopefully not too much cynicism. Having said that, I felt that what goes on outside the shows seems to interest people more than what goes on inside, and that makes me a bit sad. I mean, wow, I’m not sure if it’s really very good for fashion to see this whole flock of people waiting to be photographed. I mean, wow! Things have changed…

Just to go back to Tom Ford. What do you think about the transformation of Tom Ford the individual who was so deeply linked to a house to now Tom Ford the brand going from strength to strength?

NG: People have to understand that he has his own signature which belongs to him, and which he is expressing today. I have lots of admiration for Tom because he really knows how to build a luxury house. With the free time I’ve recently had, I’ve been able to visit lots of stores wherever I’ve been. I’d not seen much of Tom’s collections in the past because we don’t see that much in the press, but his merchandising is just as impressive as it was back in the day. I was amazed by the bags and the shoes in his LA store and in Harrods; it is so much more significant than I imagined.

What are your thoughts on the importance of, perhaps above anything else, accessory sales?

NG: Well, I’ll say this: I think the pre- dominance of accessory designers in fashion houses proves just how much easier it is to make and sell accessories than clothes. I totally respect the bag designers, but ultimately they are…

…bag designers.

NG: It’s not the same thing. But I find this need for success exciting, and it’s a good challenge. I’ve always liked accessories. I wanted the accessories to become a major part of the Balenciaga brand. Maybe that was the Tom Ford effect once again because from very early on I had no issue with the importance of accessories. I love making them too.

As we’ve had a question from Tom Ford, I thought we should have one from Domenico de Sole too. He asks the question probably everyone in the industry wants to know: ‘What are your plans for the direct future?’

NG: Ah, a question from Domenico, that makes me happy! To be honest I really can’t say anything specific at the moment other than things are looking really positive. I’m hopefully going to be making an announcement some time soon.

Are you thinking more Azzedine or Armani in terms of scale and philosophy?

NG: It’s exactly that. That’s the heart of the matter. It’s a luxury having this opportunity to think, and it’s a greater luxury to be able to say that everything I’ve built over the last few years has opened up some very lovely possibilities. Choice is perhaps the greatest luxury.

Is your own name Ghesquière present in the future projects?

NG: I can’t really answer that.

PPR recently changed their name to Kering. Hedi Slimane changed the name of a brand which has existed for decades. Do you think the name of a brand is something intrinsically important? Is it as symbolic as we think?

NG: The name is important, but it’s the substance you give it that counts. There are names that carry lots of substance already, and the accompanying images create the desire. The best combination is when both are combined: a desirable name which already carries lots of things and someone with a creative vision. This was something I’d already envisaged even before I left Balenciaga.

Today are you in a phase of creating something from scratch, or are you associating yourself with something that already exists?

NG: A little bit of both. Because even when you’re working with a heritage that already exists, there is so much that needs to be completely rethought out, and that’s an interesting exercise. But at the same time, there are moments of freedom where you imagine what you want to do for yourself.

Does creating something start with a creative vision or a business strategy?

NG: I think it starts with a creative vision, but to have a creative vision you have to be able to analyse the missing elements. That shouldn’t become the principle criteria, but it is interesting to learn about the market and analyse it. That’s why this period of time is so great for me, to see what’s going on. What works, what works best today, what doesn’t work so well. So I think it’s great being able to do my own review of the market and see what works best. This proposition is also a deduction of that: it’s a creative impulse that’s totally free and yet assimilated with what’s going on with the market.

What do you think about the recent trend of designers becoming names and brands themselves?

NG: How do I answer this without being… I think there are certain choices that haven’t really surprised me. There’s a level of expectation that’s different for everyone and for every group. I think there are associations which have harmed designers’ reputations, but generally there’s been a major shift towards the cheapening of fashion going on these last few years. Thankfully, there are counterexamples, of course.

I sense you don’t think there are many.

NG: The brands have become so powerful that the identity of the designer is secondary to the identity of the brand. In that case it’s up to us, the designers, to prove that we can have a different point of view and a personality.

Are you working with any groups right now?

NG: Yes, several.

Did you go looking for them, or did they come looking for you?

NG: It didn’t happen like that. These are principally long-term exchanges, but there are also completely new pro- jects. It’s interesting to analyse the possibilities and scenarios that exist with different groups or investment groups that aren’t even in fashion, but that want to get into the luxury domain.

Do you think that today you need to be independent in order to be able to express yourself?

NG: I think having experienced a group, someone like Tom probably needed his independence. I also think that you can be independent within a group too: Phoebe is a good current example. You get the impression that she is making her decisions freely, and yet she’s playing the business game.

Is there a price on your head? Does that make you feel uncomfortable? ‘He’s worth this, and we expect this from him?’

NG: I don’t really think of it as a price, more an image. I’ve been at one house for 15 years; I haven’t jumped from one house to another or wanted to become a ‘star’ designer. I’ve economised in some ways and given everything in others. Modesty aside, it strikes me as normal too that they think I can give a brand image to different people. It’s a sector where I can create desire.

Can you keep on creating new silhouettes forever?

NG: I think so. We’re always saying that we’re at the limit of a cut or a precision, and then new innovations and techniques or new fabrics suddenly allow us to go further. There might never be another revolution like the New Look or Chanel or Poiret, but silhouettes will continue to evolve.

Do you think it’s imaginable that such radical movements will happen again?

NG: Yes. I’m not sure if it will be in our life time, though, because I don’t think this era will be considered the most radical, to be honest. Major movements in fashion have always accompanied social and human revolutions, those events when there has been so much to say.

Technology and the arrival of global communications have definitely marked our era. To what extent has that influenced you?

NG: The digital precision, the zooming in on images, the mega high definition photos, that’s completely changed the way we work. I’ve always been very demanding in that area, but it multiplied when I realised the possibilities of precision. Everything had to be impeccable. I was already a perfectionist, so it suits me well.

Are there tools, technique, and pro- grams that you use today that weren’t heard of 15 years ago?

NG: Oh yes, there’ve been loads of innovations in the fabrics. I’ve stuck things together which I’ve been told would never stick. There have been things that I’ve produced after having been told it would be impossible. And then two seasons later, the trade fair Premiere Vision was full of fabrics inspired by my sticking.

Are you on Facebook and Twitter?

NG: I have a Twitter account because I wanted to do one for various reasons, but I think I’ve done three tweets. It’s pathetic! I’ve never opened a Facebook account, nor Instagram. But things like Tumblr which allow people to compile ideas and images, I’ve been doing that since I was a kid instinctively. I compile and compile naturally. Images, memories, writing, I hoard it all in my mind for later on. Sometimes at Balenciaga, I would research things that I knew I wouldn’t use straight away, but I’m a pretty good archivist.

Are you currently consulting the archives of another house and its heritage?

NG: Yes. And it’s something that has always interested me. I’ve always been curious about that. But something I’ve learnt is that there are a certain number of names that have gone into the collective heritage of fashion because they’ve made a powerful impact on fashion his- tory, and so no one holds back in reusing or borrowing from them every sea- son. It’s the case with lots of big names. So yes, I’m getting ready for that exer- cise but in a wide-scale way; it won’t be limited to one single house.

Are you the kind of person who wakes up at 4am with ideas that you have to note down?

NG: I’m more the sort of person who goes to bed at 4am with far too many ideas that stop me from sleeping!

These days, designers come from all sorts of different backgrounds, not always having followed a classic path; they can be business people, pop stars, stylists…

NG: …footballers’ wives.

These days, being a fashion designer seems to be the ultimate marketing strategy. To what extent do you think this has cheapened the status of the designer?

NG: You said it: it has cheapened the designer. When I see celebrities and all their insignia, I just think, ‘Wow, how much longer are people going to be duped for?’ It reminds me of Japan in the 1980s when they kept inventing things thinking it would last forever. So I say, ‘Watch out!’ There are some people who have made it work. There isn’t a real background required to become a fashion designer, so there are people who discover it as a vocation later in life, and I respect that. I just don’t like it when it’s showy with big events and money being thrown around; when it creates a confusion with desire. Then again, in the 1970s loads of celebrities and pop stars had their own lines on a different scale; it worked and was very localised. It was the same in the United States with their own lines of clothing. There were also the licences. In fact, a lot of these labels are like an updated version of a licence. You really have to be careful.

What’s likely to happen?

NG: I think some brands will wake up in ten years and suddenly realise how vulgar they’ve become. Ultimately, it’s about making a lot of money very quickly, which they succeed in doing. Celebrities have become designers, and designers have become celebrities. I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but it’s certainly been good for some people.

You haven’t really gone in for all that designer-as-celebrity scene.

NG: It’s the distraction that I cannot stand. People have accused me of being snobby or pretentious, but to be honest the main reason I never really went in for the fashion social scene was because I was working all the time!

Have you attended promotional events thinking, ‘Oh no, I’ve really sold my soul to the devil?’

NG: Occasionally. I’ve played the game when I’ve had to: the first prize I received was the VH1 Fashion Award in about 1999. I found myself on stage with James Brown, and I’d only been working for two years!

So Nicolas Ghesquière won’t be designing a Diet Coke bottle any day soon?

NG: I’ve never been asked, and I think they clearly have a strategy in their choice of designers and celebrities.

But what about being recognisable outside the world of fashion, do people stop you in the street?

NG: It does happen, occasionally.

What does it feel like?

NG: It depends if it’s nice. I mean, it’s rarely nasty, but it happens more in the States, or the Anglo-Saxon countries, where people are more expressive than in France. I grew up in a little provincial town in France where everyone knew one another, so I don’t have a problem with it. I mean, I’m not exactly hassled either.

What does it feel like having hundreds of people swarming up to you backstage saying, ‘J’adore, it’s sublime, incredible…’?

NG: It’s very overwhelming. I didn’t know how to deal with it when it started; I just wanted to hide. But at the same time, it’s kind of all these people you don’t see very often to take the time, so they deserve some of your attention. But at the same time, that whole scene can mean nothing; especially if the show’s impression wasn’t as good as people made out backstage, and the press officers tell you a load of nonsense… You learn how not to take it personally, and then take it personally.

What’s the best advice you’ve been given?

NG: Marie-Amélie once said to me, ‘You have to have a global vision.’ She meant thinking globally in terms of fashion. That was at the beginning of Balenciaga. Anna Wintour has also given me good advice.

When did you first meet her?