Fashion’s master storyteller, Tim Blanks, spins a yarn or two.

By Jonathan Wingfield

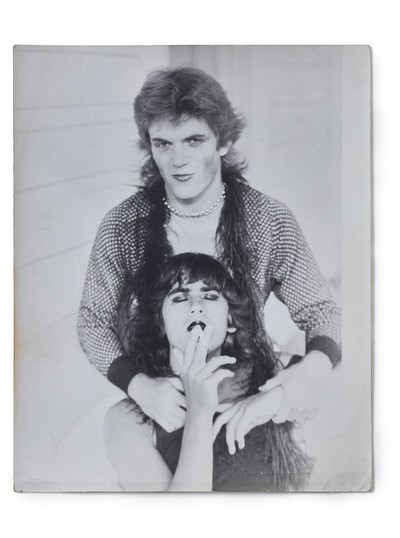

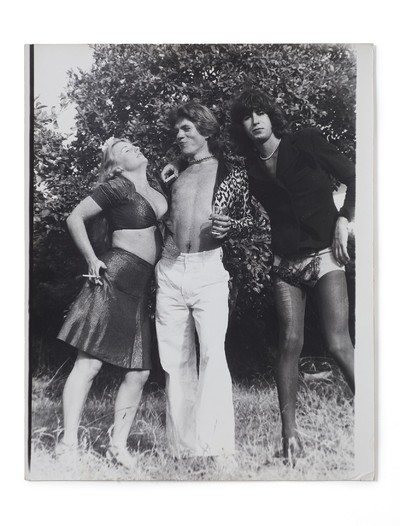

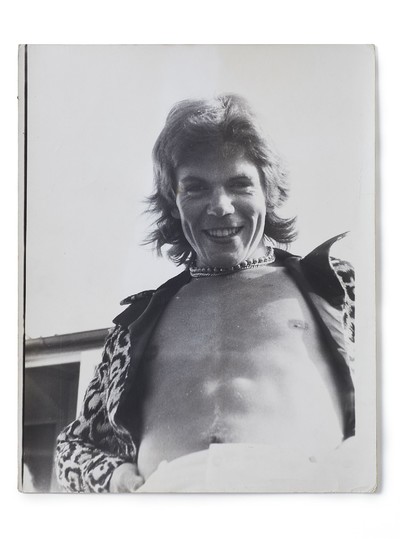

Photographs by Juergen Teller

Fashion’s master storyteller, Tim Blanks, spins a yarn or two.

Tim Blanks’ presence in fashion is as bright and colourful as the shirts he often wears on the front row. A longstanding fixture at the seasonal shows – he’s been covering the New-York-London-Milan-Paris circuit since 1987; initially as a TV presenter and since 2006 as a reviewer – it’s Blanks’ infectious mix of curiosity, authority and cultural erudition that forms the basis of his critical eye. Astute and influential (few openly voice an opinion before they’ve read the Tim Blanks review), his show critiques are crafted with the same passion and savoir-faire as the couture gowns he observes on the catwalk.

As editor-at-large at today’s fashion-media sensation, The Business of Fashion, Blanks delivers written reviews, features and interviews, as well as live-event Q&As and online punditry, to a digital audience of CEOs and students alike; his expanding array of ‘content channels’ mirroring the ever-increasing global interest in the fashion industry itself. Blanks was previously editor-at-large at Condé Nast’s much-cherished-now-discontinued online catwalk resource, Style.com and its menswear counterpart Mens.Style. And prior to that, between 1989 and 2006, he wrote and presented Fashion File, a globally

syndicated TV show out of Toronto that offered up a lively snapshot of supermodels and star designers to the MTV generation.

But perhaps more than any professional entry on his CV, it is Tim Blanks’ own rich and meandering life story that today makes his voice in fashion so unique and original. By his own admission, Tim grew up a “a fat, queenie, super-unpopular kid” in late 1960s Auckland, New Zealand. A prodigious student yet an “outsider’s outsider”, he lost himself in a world of music, art and glamour, delivered to him via the pages of, first, his grandmother’s Life and Time magazines, and then the era’s influential British music ‘inkies’, Melody Maker and NME.

For young Tim Blanks, this was an age defined by David Bowie and Lou Reed, Andy Warhol and the Factory, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, the Vietnam War and Watergate. And by joining the dots of what he was reading about – culture and image, escapism and political unrest, social climbers and downtown drag queens – he unwittingly created the blueprint for his ensuing journalistic career.

Today, a Tim Blanks show review is as likely to reference a John Cale viola drone solo as it is the bouleversé braiding on a Dior bar jacket. This isn’t cultural showboating or one-upmanship, it’s symptomatic of Blanks’ schoolboy enthusiasm for sharing his treasure chest of references. It harks back to when young Tim would seek out kabuki theatre and Kansai Yamamoto’s body suits because he’d read Bowie mention them in Record Mirror. And ultimately, ‘Tim’s Take’ makes the fashion-media landscape a more nourishing and culturally enriching place for us all.

In a series of conversations with Tim over the summer months in London, System discovered tales of a life that started on the sidelines and now resides firmly in the thick of the action – while along the way recalling lively jaunts in London squats and Bel Air mansions (with housemates Bryan Ferry and Jerry Hall), naked backstage mania with Claudia Schiffer (Claudia, not Tim), feuding (briefly) with Gaultier, and having something refreshing to say about pretty much anyone and everything. So pull up a seat, and read Tim Blanks.

Part One

The outsiders’ outsider

Jonathan Wingfield: Music seems to have been the portal to everything in your life and career, so let’s begin with that.

Tim Blanks: The first music I was drawn to was Mary Poppins, West Side Story, and The Sound of Music, which made my mother despair because she loved the Beatles, and wanted me to love them, too. My kidneys failed when I was 11 and I clearly recall her visiting me in hospital, clutching a copy of Ella Fitzgerald’s version of the Beatles’ ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’ as a get-well gift. But the first Beatles album I voluntarily got into was the White Album, which, believe it or not, was Rei Kawakubo’s inspiration for starting Comme des Garçons.

Is that something you’ve discussed with Rei Kawakubo?

When I asked her about it, she just shook her head! But I think Comme des Garçons sometimes uses that hand-sketched apple emblem because of the White Album record sleeve; it’s a subliminal recognition of the importance of the Beatles in the history of Comme. I think when Rei Kawakubo heard the liberation in that music, it inspired her to be a free spirit, above and beyond whatever she was doing at that point.

Was teenage Tim Blanks experiencing a similar moment of liberation in Auckland?

I couldn’t have cared less about freedom! I was too busy soaking in the bath every Thursday night for hours, listening to the local radio station playing the John Peel show via the BBC. That’s how I discovered Sandy Denny – a total epiphany – and then promptly made my mother drive me downtown to Wiseman’s Records, where I bought What We Did on Our Holidays by Fairport Convention. Sandy Denny really struck a chord with me – maybe because I was coming out of this Julie Andrews musicals vibe – and I still consider her the greatest female voice of all time.

What was everyone else at your school listening to at the time?

I went to an all-boys school: everyone was into Jimi Hendrix and the Doors, which just didn’t register with me at all. Well, Jimi Hendrix did, just much later on. I still love Hendrix.

What were you like at school?

Archetypal nerdy. A fat, super-unpopular ostracized kid; everyone thought I was queenie. School was basically awful, so I gravitated towards a mid-city record store called Taste, where the staff were all older and clued-up about what was hip and happening. That’s how I discovered bands like Tyrannosaurus Rex. If you played that stuff to people who liked Jim Morrison, they thought you were from another planet.

Did the record-store crowd immediately accept you as one of them?

There was this fabulous woman working there called Candy Alderton, who I bonded with. She also happened to be a stripper. How a fat, queenie 14-year-old schoolboy bonds with this extraordinary creature I’ll never know. During one summer heatwave, she was on the front cover of the New Zealand Herald. You know when newspapers do that headline, ‘Phew, what a scorcher!’? Well, they used it on a photo of Candy wearing a string bikini, and romping with her dog. The caption said: ‘Candy Alderton, 24, and her dog.’ I remember seeing that and squealing ‘Wow! I know her!’ and my mother being, like, horrified!

Would you say you were particularly smart or academic as a kid?

I was top of the class. A prodigious student. My mother’s mother raised me: she had a telescope and would teach me about the sky and the planets, and got me reading when I was three years old. Teachers gave me the newspaper to read at the back of class, while the others were struggling with Janet and John. My younger brothers would be given scooters for their birthdays and I’d get books about the movies. I was just always way advanced in reading and thinking.

‘I had a total crush on Valda Kerrison, this beautiful redhead hippie-maiden type who was always barefoot, in a shawl, and on acid.’

Did you see that as your escape route?

Very young, I made a deal with my parents: if I passed the exam and got a scholarship, they’d let me go to university at 15. Which I did. I was wide-eyed and quite untutored in the ways of the world, suddenly surrounded by people who most definitely weren’t. I had a total crush on Valda Kerrison, this beautiful redhead hippie-maiden type who was always barefoot, in a shawl, and on acid. I was this googly-eyed boy who didn’t even drink, hanging around with these extremely seasoned ‘heads’ – that’s how they were referred to back then – so it was quite an eye-opening education for me.

Had the hippy scene hit Auckland in a big way?

It was very localized. Growing up in New Zealand, you were always so painfully aware that everything was happening somewhere else. You were just so geographically outside the loop. But I was drawn to people who, in their interpretation of what was happening elsewhere, looked incredibly gorgeous. And it was exhilarating to be hanging out with these real-life versions of what had previously only existed in my grandmother’s copies of Life and Time magazine. It’s funny, I just did Anna Sui’s book with her, and while I was growing up in New Zealand, she was growing up in Michigan, but we were both reacting to exactly the same stuff. Anna remembers that Andy Warhol Factory story in Life magazine that I was obsessed with; or those colour photos of people skinny-dipping at Woodstock; and the pictures in Vogue of Edie Sedgewick standing on a leather rhinoceros.

That says a lot about the mass-marketing of magazines at that time.

They were a huge deal: that mix of war and glamour and music and art. Vietnam, Warhol, Elizabeth Taylor marrying Richard Burton in Montreal, the Rauschenberg Bonnie and Clyde cover, the Lichtenstein gun cover… I swear, Life magazine must have shaped the minds of so many kids in the 1960s because it was your window on a world you simply weren’t living. It reminds me of what Lou Reed said: ‘If I’d been reading about the Factory and not been able to get to New York, I would have killed myself.’

Is that how you felt?

No, because I was still so young. But imagine how those things touched the sensibilities of kids who felt like outsiders. Or in my case, an outsider’s outsider. I remember when the movie Woodstock came out in Auckland, and seeing these incredible long-haired hippies walking into the local cinema in their full Technicolor-dreamcoat business. One of them had ‘FUCK’ written across his forehead, and I remember thinking, ‘Wow, I love these people!’

Did you become a fully signed-up hippy?

Funnily enough, there was this fabulous transitional moment when I started sharing the music that I’d discovered by myself with these older, groovier people. I’d play them Ziggy Stardust or Roxy Music’s first album and they were like, ‘Eurgh!’ Didn’t get it at all. All of a sudden, they seemed a little less cool, so I moved on, and created my own little glam-rock micro-clique.

Did glam rock feed a parallel appetite in you for clothes and fashion, or at least a fascination with image?

Not initially. You couldn’t really see what anybody looked like. There were no videos; there simply wasn’t the scale of widely distributed imagery we’re now so accustomed to. You’d see pictures in Melody Maker – my copy of which would arrive in Auckland six months late – but everyone just looked like fat old, bearded hippies. There was never anyone who looked fabulous, except the Velvet Underground and Nico. Sunglasses at night seemed like ‘a thing’.

So, it really was just about the music.

Well, glam rock did change that. There might have been six people I knew in Auckland, strutting around in looks we’d fashioned for ourselves. I’d be riding my Honda 19 in these ridiculous glam-rock outfits, and we’d show up in the front row when Roxy Music came to play in Auckland. Ironically, it was all the hippies at the back who’d be screaming, ‘Sit down!’ at us. The baton had truly been passed. And in our efforts to re-enact what we thought was happening everywhere else, I realize now that we didn’t do such a bad job.

Were you making your own clothes? Or shopping in thrift stores?

When the Stones came to play Auckland, I remember putting a look together for it. I found an old jacket with a gold lining, turned it inside out and had my friend Eve sew gold dice – as in [the Stones track] ‘Tumbling Dice’ – down the lapel. I was friendly with a guy called Colin McLaren from Elam Art School in Auckland who used to paint white canvas trousers with different-coloured stripes around the hem. So, I wore these traffic-light trousers that he made for me – red, amber and green – which got me into trouble with the police. Traffic-light acid was the big acid at that time, and because I had these trousers on, they thought I was a drug dealer.

‘I wasn’t on drugs, but when Jimmy Page played guitar on ‘Dazed and Confused’ I idiot-danced so furiously, my entire body chemistry altered!’

Had designer fashion hit your radar at this stage?

There was no such thing as fashion; there weren’t stores per se. The first designer fashion that came to Auckland was Yves Saint Laurent ties for men. You didn’t shop, it didn’t exist; you didn’t even go to restaurants, there weren’t any.

I presume live gigs were a rarity in New Zealand, too.

Totally. Led Zeppelin were the first international act to play in Auckland. By then, I loved Led Zeppelin, loved cock rock, loved a meaty guitar solo. I went to that gig with people who were much older, and who’d all taken acid. I didn’t take drugs, but when Jimmy Page played his guitar on ‘Dazed and Confused’ with a cello bow, I completely freaked out. You know that footage of those people at Woodstock or at the Stones concert in Hyde Park doing what I call ‘idiot dancing’?

Wigging out.

Yep. Well, I idiot-danced so furiously, my entire body chemistry altered! [Laughs] There were a couple of things that had a massive impact on my home life and that Led Zeppelin concert was one of them.

And what was the other thing?

My father dying in 1972. His death was the canvas against which everything else played out. It’d be too convenient to say that music was my refuge, but there was certainly a tension.

How strong was the urge to get out of Auckland?

You have no idea! As I said, everything was happening somewhere else. These days, of course, New Zealand is where everyone wants to be…

Thanks, Lord of the Rings.

And it is the most beautiful country in the world, but that means shit-to-a-tree to a 16-year-old speed-freak.

I thought you said you were wide-eyed and innocent.

That changed. Speed was the first drug I ever started taking with any conviction. Why? Well, you know, I loved the idea of the Velvet Underground and that whole sleazy New York scene. But the funny thing is I ended up escaping to London, instead of New York.

What took you to London?

Officially, a post-grad thesis. But honestly, Bowie. This was 1974.

Was London your first experience outside of New Zealand?

First ever time on a plane! Just after take-off, we flew through a hurricane above Auckland. There was a priest on-board giving last rites, and cabin announcements to say that children should go and sit with their parents up in first class. I just figured that’s what flying was like all the time.

Did you know anyone in London?

Only one connection: friends of my mother’s friends, so my friend-slash-boyfriend Jude and I got off the plane and went to stay with them. On the journey from Heathrow into London we passed the Hammersmith Odeon, where Bowie hadn’t long done his Ziggy Stardust farewell concert. When you’re a fan, all that stuff really resonates. That first day in London was a Thursday, and I remember watching Sparks play ‘This Town Ain’t Big Enough for the Both of Us’ on Top of the Pops. I instantly knew I was where I should be.

Did you have any fixed plans to work? To write?

Within about two weeks, I’d got completely distracted from the thesis, fell in with some pretty ghastly company, and started writing about music. I’d already been writing for a little music magazine back in Auckland called Hot Licks, so I began writing stuff for them, as the ‘correspondent from London’. You cannot imagine how easy it was just to call up a publicist and say, ‘Hi, I write for a magazine from New Zealand, and I’d love to interview…’ so and so. I called up all the people I loved: Peter Hammill, for example, because I was obsessed with Van der Graaf Generator; Kevin Ayers from Soft Machine, Brian Eno…

What about Bowie himself?

Bowie was unavailable at that point, but [his management company] MainMan packed me off to the Château [studio] to interview [Bowie guitarist] Mick Ronson who was recording his Slaughter on 10th Avenue album.

‘Within two weeks of arriving in London, I’d got distracted from my thesis, fell in with some pretty ghastly company, and started writing about music.’

Can you paint a picture of what London was like at the time?

Grim. A black-and-white city in which every house had a ‘For Sale’ sign outside. Every day and night was accompanied by a panoply of IRA bombings. You’d be at a gig, boom! A party, boom! Horrible, but fabulous, too.

Which part of town were you living in?

Initially, Islington. I found a place to live off the notice board at New Zealand House, then I moved into a squat inhabited by the most extraordinary people. And the parties we had there were amazing. Look at any magazine from that time and all the best people were at those parties. Too many drugs, of course. Not me, but everybody else got completely fucked up, and an alarming number of people wound up dead.

How acute was the décalage between the glam-rock fantasy and the realities of that scene?

This is something that really interests me. If I think objectively about it now, how on earth could you survive the horrors of the daily existence of doing nothing, being surrounded by such dubious people? I mean, in your own squat, people would rip you off the whole time. My beautiful T. Rex T-shirt… vanished!

Who were your closest friends?

Among others, there was Ritva Saarikko, a photographer I’d been introduced to in New Zealand who showed up one day in London. I was interviewing Brian Eno that afternoon, so she tagged along and met him. Or rather, Brian met her. He called me up straight after and said, ‘Would I be stepping on anybody’s toes if I asked Ritva out?’ They ended up becoming an item for four years; she also did the record covers for his albums Taking Tiger Mountain and Before and After Science.

It seems incredible to think that one of Auckland’s only totally obsessive Roxy Music fans ended up in Brian Eno’s social circle.

It seems surreal now but you could go anywhere then and see anyone. Ritva and I were living at Vale Court15 and I remember this fabulous moment when we were sitting in the window, watching John Wayne shoot the movie Brannigan right over the road from us. You could go to El Sombrero and Angie Bowie would be dancing with Dana Gillespie. Or you’d go to the Casserole restaurant on the Kings Road and see people. Although because I was a speed freak I only ever ate desserts there. I’d have a small portion of the trifle as my main course.

What about the presence of fashion in London at that time? People like Brian Eno and Mick Ronson had a pronounced sense of style.

Yes, but their girlfriends or friends made their clothes. Brian Eno’s clothes for Roxy were made by his then-girlfriend Carol McNicoll, and Mick Ronson’s clothes were made by Freddie Burretti, who also made Bowie’s clothes. For shopping, there was Swanky Modes in Camden, and Laurence Corner near Euston Station where people used to get their Bryan Ferry army-surplus-y look. Then there was the McLaren and Westwood shop Too Fast to Live Too Young to Die, which then became Sex. But South Molton Street certainly didn’t exist as a fashion street, other than Browns, which probably stocked Armani in 1977.

Were you deliriously happy to be in London at that time, finally in the thick of the action?

Yes. But I was also really ill. I was vomiting blood because of the speed habit. There were days when I would take so much that I thought the blood vessels in my eyes had burst because I could only see purple. I’d buy my speed down in the Piccadilly loos. One night I was in there and Pasolini was casting for The Canterbury Tales; checking out the male hookers because he would cast guys with huge penises. It was fabulous and awful. Like London.

‘I’d buy speed down in the Piccadilly loos. One night Pasolini was casting male hookers for The Canterbury Tales. Fabulous yet awful. Like London.’

And spiralling out of control.

It was clearly going to go horribly wrong at some point! And it did. I got an ulcer and, after less than a year, had to return to New Zealand to regroup. Luckily, I was still young.

Having escaped Auckland and landed in London, didn’t it feel hugely underwhelming to be returning home?

Sure. But I knew I had to get myself better. Did that, then moved to Sydney, which ended in a cloud of mega Mandrax abuse, and so I drifted back to London once again. I called Ritva and ended up living with her and Brian. He was recording “Heroes” with David Bowie at the time, which was kind of exciting. Every weekend he’d come back with an acetate of the song they’d just completed and I’d force myself to be super casual about it. Anyway, they were breaking up and one day in 1977 or 1978, Ritva just announced: ‘I have to leave London because I don’t want to be with him anymore. Let’s move to America.’ So, we did. I had nothing to lose.

To New York?

No, I ended up in Los Angeles. Working for Bryan Ferry. Living with him and Jerry Hall in Leslie Caron’s huge house at 474 Cuesta Way, in Bel Air.

How does a glam-rock-obsessed teenager in Auckland end up working for Bryan Ferry in LA?

I forgot to say, but while I was back in New Zealand, licking my wounds, Roxy Music showed up on tour. I knew them through Brian [Eno]. I happened to be doing my full Bryan Ferry look at that time, too: black hair, tweed jacket and corduroy pants. When I met him, he looked me up and down and said, ‘Oh God, if I ever do a movie of my life, you can be my understudy.’

Why emulate Bryan Ferry’s look, as opposed to, say, Bowie’s?

You couldn’t really dress like Bowie; you couldn’t really do a Kansai Yamamoto24 body suit on a stocky New Zealander, but you could do a tweed jacket and khakis. Anyway, I rounded up a whole bunch of really gorgeous girls for the Roxy gig in Auckland, which, of course, made the band very happy, and then later on Bryan got in touch, wanting to know if I’d work for him back in London. That didn’t work out, but a couple of years later I ended up being shipped out to LA to work for him.

What was your official job title?

They called it Personal Manager on my visa form.

Describe a working day with him.

Bryan would say, ‘So, what are we going to do today? Let’s go to every house that Raymond Chandler lived in’. So we’d climb in the car and just drive around town. The thing is, nobody really knew Bryan in LA, until he’d walk into somewhere like Amoeba Records. Everyone there knew who he was, so he’d have his moment of ‘fabulosity’.

Wasn’t he writing or recording music?

He was supposed to be making the cover-versions album that became The Bride Stripped Bare, but it wasn’t such a fruitful period for him. I remember he’d be asking, ‘What songs do you think I could cover?’ I’m pretty sure I suggested ‘What Goes On’ by the Velvet Underground. Had that whole experience happened to me a couple of years earlier – when Bryan had first asked me to go work with him – it would have been so amazing. But by this point I was so into punk that I felt completely disconnected from Bryan and Bel Air. And, as you can imagine, Bryan wasn’t remotely curious about punk. Once again, the tide was shifting. For me, at least.

Part Two

Discussing Sonic Youth

with Shalom Harlow

When were you first aware that there was an industry in fashion, that there was a community of people working and making money out of it?

If Life was my visual record of the 1960s, then French Vogue was my visual record of the 1970s. I was a huge fan of Guy Bourdin’s photography in French Vogue and for those Charles Jourdan shoe ads – those pictures are staggering – and since I’m quite anally retentive, I’d make a point of seeking out his work, and that of people like Helmut Newton, of course. That in turn took me to finding out the models’ names, and joining the dots with music. So, when I saw Josephine Florent in Vogue, I made the connection that she was Robert Palmer’s girlfriend, and the girl on the cover of his Sneakin’ Sally Through the Alley album.

When did your writing start to become more focused on image and style rather than predominantly music?

I’d always been writing music pieces that brought in other elements: H.P. Lovecraft, James Dean, teens, nihilistic stuff. In Sydney, I was writing weird, off-the-radar think pieces for a big music magazine called Rock Australia Magazine, very influenced by people like Lester Bangs and Ian MacDonald. They were never style pieces per se, but there was always an angle. Then, I moved to Toronto in 1978 and started writing about all sorts of things: couples in the art world who worked together; interviews with Warren Beatty or Jack Nicholson for more conventional ‘style’ pieces for a magazine called Close-up; I even wrote about Orlando golfing holidays. I mean, me golfing? [Laughs]

‘Then I ended up in Los Angeles, working as Bryan Ferry’s personal manager. Living with him and Jerry Hall in Leslie Caron’s huge Bel Air mansion.’

Can you remember the first fashion designer interview you did?

Zandra Rhodes for Close-up, but she fell asleep two minutes into the interview. She had narcolepsy. I eventually excused myself from the room an hour later. The auspicious debut! [Laughs]

Were you actively pursuing a job on a fashion title?

All I wanted was a full-time job, and Toronto Life Fashion were the only ones prepared to offer me one. I became the features editor, which was great because I’d go on trips to Japan or Italy. But then the editor left and I replaced him, which meant the creative aspect of work promptly shunted to a halt because I was too busy massaging the advertisers. Honestly, I would never want to be a magazine editor ever again.

How was Toronto in the 1980s?

Such an incredible city; so much money there, too. It was the axis of Europe and North America, so everybody who wanted to test-run their product – whether that ‘product’ was a new Armani fragrance or a Simple Minds world tour – would launch in Toronto before heading over to Midwest America.

Was it for Toronto Life Fashion that you started covering the shows?

Yes. We’d done collections coverage before, but I was the first person to actually go to the shows. That would have been 1987.

What was the first international fashion show that you attended?

The first I remember was a Yves Saint Laurent couture show; the collection with the Braque guitar and the Picasso doves. As an introduction to the shows in Europe, it was pretty extravagant. Shows like Saint Laurent and Ungaro were staged in hotel ballrooms, would last for at least an hour, and there would be 150 looks. Besides Bill Cunningham, there was no pizzazz outside; they were quite sedate. All the important people sat at the end of the catwalk, while the photographers were sat up and down it, making sitting in the front row tedious. Which didn’t trouble me, since I was always in standing. I didn’t care, I was just glad to be there. As Helena Rubenstein said: ‘Even if you’re by the toilet door at Le Cirque, you’re still eating the same food as Jackie Onassis.’

Weren’t Gaultier’s shows the antidote to sedate couture?

Totally! Ready-to-wear was obviously a different experience, especially in Paris. Gaultier, Mugler, and Martine Sitbon became the hottest tickets. There would be an absolute party at those shows, with busloads of drag queens coming in from Eastern Europe. When Vivienne Westwood showed at Azzedine [Alaïa]’s studio, which I think was 1991, that show was an hour long, and the interplay between the audience of freaks and the models was incredible; models were laughing and running and joking.

That’s so rarely the case today.

If you could pinpoint when models were told to stop smiling, stop being human and stop interacting, that was about three or four years later.

When did you start getting accepted as a regular fixture at the shows?

I did a little research and found out that it was good to send Denise Dubois at the Chambre Syndicale a big bunch of flowers from Moulié-Savart, her favourite florist. She was probably surprised to get a big bunch of flowers from Tim Blanks, but it worked and I started getting seats. It’s funny to think about that because I wasn’t ambitious at all. Never in my life have I been driven! The secret to my so-called success is no secret: I’ve just been doing what I do, early, patiently, for a long time. I proposed the TV show that became Fashion File to the CBC [Canadian Broadcasting Corporation], and that started in 1989. And in the whole time I did Fashion File, so many people came and went trying to do something similar. And my point was always the same: it was never about me; it was always about them.

‘I’ve always felt that you should take designers a little seriously, show them some respect. Don’t just march up and say, ‘So, tell me, are you a natural blonde?’’

‘Them’ being the people you were interviewing?

I knew that people wanted to look at Claude Montana or Thierry Mugler or Jean Paul Gaultier or Karl Lagerfeld. That was who I wanted to look at! Not look at me – I didn’t want to be a star.

Were you surprised that fashion on television remained such an untapped medium?

I’d already worked a bit in music and in film, and I’d already been going to fashion shows, so it seemed obvious to me that television would be such a refreshing arena to present all these amazing people and places in fashion.

Why was that so refreshing at the time?

Because there wasn’t anyone doing it. Elsa Klensch’s show on CNN was like Tales from the Crypt. Jeanne Beker for Fashion Television in Toronto was doing it in such a populist way. Then there was Marie-Christiane Marek at Paris Première, but she didn’t speak English. And then there was me. In 1989, there was literally the four of us backstage. Then the supermodel thing happened and it went from 4 to 400.

Overnight?

In a flash. And of those 400, 370 of them were absolute fakes. Claudia Schiffer would be stark naked in a cabine, and there’d be somebody pointing a camera at her. It was just crazy. I’d say to the security people: ‘You should check how many people in this room actually have film in their cameras.’ You know, how many of these people aren’t just busy leching at all the models?

In what ways did your approach to documenting fashion differ from everyone else’s?

I’ve always felt that you should take people a little seriously, just show them a little respect. Don’t just march up to a designer and say, ‘So, tell me, are you a natural blonde?’ I’d ask models if doing their job was changing the way they saw themselves in the mirror. Or I’d just end up sitting with Christy Turlington and talking about the books we liked. Or discussing Sonic Youth with Shalom Harlow.

It seems so innocent.

It was! Designers would say to me, ‘I didn’t know what I’d put on the runway until I talked to you’, because I’d have said something like, ‘The show reminded me of this Visconti scene’, or, ‘I loved it when you used the music from Vertigo’. I just think you will never ever lose by giving people credit for intelligence. Elsa Klensch was the goddess of fashion on television and her questions were like, ‘Tell me about the length of the clothes’. I just couldn’t do that. But my shortcomings as a traditional fashion journalist helped me carve an original path.

Sonic Youth and dress lines are absolutely worlds apart.

I was thinking the other day about how Christian Lacroix’s backstage food buffets were just works of pristine art. People don’t do it anymore – it’s too expensive – but it was another world that was so worthy of celebration, above and beyond, ‘Here’s another hoop skirt, here’s a puff skirt’. Ultimately, I’d say that my curiosity humanized the fashion industry. Besides, you can’t really imagine Elsa Klensch getting down on her haunches and asking a model about Sonic Youth.

Watching Fashion File archives on YouTube, that sense of total access is palpable, and everyone was so unguarded in front of the TV camera.

What can I say? It was new. You’d see it all: models melting down in rages when they didn’t get the outfits they wanted. People backstage crying when the designer had been horrible to them. Someone like Claude Montana would be shepherded in front of the camera, quivering like a baby and blinking into the lights, because his people had told him to do it ‘because everyone else is’. I remember Pierre Bergé literally pushing Saint Laurent out in front of the camera for me to interview him, and Loulou de la Falaise translating. It’s agonizing to watch, because never in a million years did Saint Laurent imagine that a condition of his job would be to perform for TV.

Others must have relished it though.

People like Lacroix, who had a natural curiosity, saw it as an opportunity. He used to call me his therapist because he was so honest. Gaultier was amazing, too – just hilarious – and so familiar with the TV format because he hosted Eurotrash. The early McQueen stuff was really good: we showed him in darkened silhouette – like he was a terrorist or a drugs smuggler – because he said he was on the dole and his face couldn’t be on screen. Most of the European designers were fantastic because they believed they had to answer any question they were asked, whereas even back then the Americans would spout a paragraph of press release. Paris was so much more tantalizing.

Sounds like a golden age of fashion from a media perspective.

It was. Everybody talks about the 1970s being the golden age of film – with The Godfather and Apocalypse Now and so on – well, the 1990s were the last golden age of fashion. Thinking about it, there’s a lot of fashion history in what we were doing for Fashion File, because quite a few of those designers have since died or, like Issey Miyake, are simply no longer available.

What’s the modern-day equivalent of all that Fashion File style of footage?

It doesn’t exist anymore. These days, everything’s an officially staged ‘set-up’, with five officially allocated minutes, and so on. None of the wrong ’uns slip through the net.

Who or what triggered that change?

When Tom Ford did his breakthrough Gucci show for Fall 1995. He really understood the game, so he ushered in the new rules: you have to wait until after the show to interview Tom; Tom has to be stood here; there has to be this kind of light on Tom, and at this angle; and you can have three questions for Tom. Which he obviously answered brilliantly. He was made for TV. But KCD35 then took the three-questions rule and applied it to every other designer they had, even if they were incapable of speech. At that point, things became much more formalized. Until then, it was open house: you could just turn up and start interviewing Kate Moss backstage. Besides Tom Ford, there were then people like McQueen and Galliano who started playing the game their way.

Which was how?

Galliano was Garbo-esque and made everyone wait for an hour or so before he’d finally appear backstage to talk to the media. McQueen simply stopped doing backstage interviews altogether. He’d disappear into a waiting car.

It seems ironic that around the same time that Tom Ford was rewriting the rulebook for how to present yourself as a media personality, someone like Martin Margiela was becoming increasingly aware of the mythology surrounding his total absence.

Sure. Margiela, Yohji Yamamoto, Helmut Lang and Rei Kawakubo never did anything at that time. But although we couldn’t film interviews with designer, we could still do pre-scripted chatty stuff to camera. I remember filming something – anything! – about Comme des Garçons outside their show venue in Paris and Marion Greenberg [Rei Kawakubo’s then-New York PR] came bounding up to me, screaming, ‘Tim, I’m so shocked! I’d told you no!’ And I said [adopting incredulous tone]: ‘Marion, we’re in the street! It’s actually public property.’

Were you making Fashion File on a tight budget?

I can’t even tell you how cheap that show was to make, and they [CBC] leeched every bean. It was selling internationally and they took every penny it made and poured it into fancy talk shows with audiences of 40,000. They never took it seriously the whole time. And even when it stopped – after 17 years – I’m sure there were people who said, ‘I told you it wouldn’t work’.

Why did it stop?

One of the first deals we made was with E! in America. E! was looking for the same thing as CBC: cheap programming to fill the hours. So they bought Fashion File from CBC and pretty soon, there was a moment when we outdid Howard Stern on E!’s ratings. But then they decided they needed a ‘personality’ to host it, so they proposed bringing in Tyra Banks.

So, she was going to replace you?

Her fee for one episode was the same as mine for an entire year, allegedly! And in that year, we’d produce four content pieces a week, 52 weeks of the year; all original programming, no re-runs. So even E! backed down on that.

What impact did Fashion File have at the time? Were you aware of the audience or industry reaction to it?

The weird thing for me is [Tim’s partner] Jeff and I moved to London at the beginning of the 1990s, so we never actually saw Fashion File. They’d send tapes, but I couldn’t be bothered to watch them. But if I went anywhere else in the world – like Mexico or Brazil, where it was shown on four different networks – it was a huge deal. Someone told me that at one point in America we were the number-one top-rated show on E! It used to go out on Saturday mornings, so Americans often tell me today, ‘Oh, I used to watch you with my mum when I was little’. Just the other week, Jack McCollough from Proenza Schouler said to me: ‘You presenting Fashion File is the reason I’m in fashion.’

Part Three

Being a critic in an age when

criticism is fiercely criticized

What is so apparent from your past is that you’ve always been a fan.

Fandom defined me. Still does.

Are there fashion designers who come anywhere near to the level of fandom that you have for pop stars?

Oh, totally! Claude Montana, ardent fan. Miuccia Prada, total rock star. Raf Simons, too.

What is it that distinguishes them from the rest of the pack?

Just their total and utter idiosyncrasy. Every collection is like a new album. If you look at Bowie from the 1970s and 1980s as being the consummate musical statement of human civilization – an album a year, and a clear evolution – so there are designers who’ve mirrored that. Quite a few actually. Every season in fashion gives you three dozen points of view and it’s very easy to pin down those that stand out.

How would you define what it is you’re conveying in a show review?

I think what I do is evocation, not evaluation. In a way, fashion is a narrative, and I’m just retelling the story. So regardless of what I am writing about, what I’m doing is trying to put the reader there. But since everyone now has such incredible access to everything, people say that destroys the role of the critic. That’s probably true, because the minute anything is online there are thousands of opinions about it. And criticism has been replaced by opinion.

And polarized opinion, at that. It’s all ‘#perfection’ or ‘that fucking sucks!!!’

Either way, criticism has always had weird, snarky connotations. When I was reviewing records I’d think, ‘Even if the record stinks, these people have spent six months of their lives making it, so who am I to gut it like a fish?’ That’s me being falsely noble now – total revisionism [laughs] – because obviously, I’d be furiously gutting records most of the time.

Are your reviews based on an accumulation of facts and knowledge, or on instinct?

Well, I don’t report; I’m not a journalist. I suppose the cop-out answer would be facts and knowledge illuminated by intuition! There is, of course, authority in knowledge, if you can make a valid point by referencing something historical in a convincing way. But you don’t want to sound pedantic in a fashion-show review.

You said you’re not a journalist. What do you consider yourself?

Good question. What am I? A writer? An eyeball on a scene? It’s that whole thing about evocation, and this notion of trying to create the scene for people who aren’t there. Obviously, that doesn’t always work. But if I mention the soundtrack, then you’ve got the song in your head, and if I then add a detail about the models’ hair, well, then maybe that evocation starts to come through.

How important is it for your writing to be accompanied by visual aids?

People often tell me: ‘I read your review and got excited, then I looked at the clothes and they were boring.’ People talk about fashion shows dying, but they never will because nothing – nothing – can replace that experience. Sure, you can see a video or a live stream, but that’s like a photo of an event; you can’t smell the blood in the bullring. Nothing can replace the immediacy of communicating a moment to 500 people who will go out into the world as your ambassadors and say, ‘Oh my God, there was this moment when the music kicked in, and the smell of incense in the room was overpowering, and…’

So you critique shows rather than collections?

Definitely. A show is what the designer wants me to see, to understand their collection. I don’t do re-sees. I’m not going to go to a showroom and write about looks that aren’t on the catwalk.

So the show review exists as its own moment of entertainment, rather than a prompt?

To me, it’s total entertainment. Fashion is quite unique from that perspective. If you read a book review that you like, you’ll go buy the book; if you read a film review you like, you’ll go to the movies; but if you read a Walter van Beirendonck fashion-show review you like, you’re not going to rush out and buy Walter van Beirendonck. Fashion criticism is the one vehicle of opinion that holds no sway over the way that people respond to the product.

‘You wouldn’t get Le Corbusier parading his maquettes for 15 minutes in front of an audience. He’d just build a building that everyone would see.’

Do you think that fashion publicists and marketeers will cry into their Walter van Beirendonck collections on hearing you say that?

No, because buying a book or downloading a movie, or going to the ballet or the theatre or whatever, is much less of an investment than buying a fabulous Dior dress.

It’s like writing about art.

It is. If you read someone’s lyrical piece about Klimt, it might enthral you, but you can’t just go out and buy yourself a Klimt. It might thrill you to read about that Dior dress, but you can’t buy it. That’s why fashion reportage is so different from all other cultural coverage.

In what other ways would you consider it different?

Well, it’s fascinating that there is a long-standing canon for every other genre of criticism – in art, you’ve got Clement Greenberg, Vasari going all the way back – and yet that just doesn’t exist for fashion. Everything about fashion just seems much more transitory; you’re not going to see an anthology of Cathy Horyn’s or my reviews, yet Pauline Kael’s collected film reviews are published in books, as are Anthony Lane’s – his book [Nobody’s Perfect: Writings from The New Yorker] is fabulous, by the way. I strongly recommend it.

Your archive of Style.com reviews is now housed in a constantly mutating online Vogue archive. How does that make you feel?

I just hope that it doesn’t get brushed away into a closet and vanish forever. I’m not sure what the final word was when Style.com moved over to Vogue Runway. I don’t know if there were decisions made about what designers would be archived. Considering we reviewed people who were only in business for one or two seasons, they probably wouldn’t have been kept. There are designers whose entire careers are not recorded in any way whatsoever. But then I think about all the shows that I filed for Fashion File, that were taped over at CBC. Lost forever. Then again, the same thing happened to entire Charlie Chaplin movies, too.

Do you think the broader world of publishing and media will ever associate fashion coverage with anything other than ‘flicking through Vogue’?

When I started editing Toronto Life Fashion, I was a lone man on the totem pole of fashion in Toronto. Besides me, there was this hideous film journalist who wrote for Now magazine – the local freebie – who kept writing about fashion for some reason. He was this big, fat, bearded man who wasn’t even a good film critic, but his hatred and venomous attitude towards fashion was startling. Yet it reaffirmed for me the power of fashion. You just wanted to say, ‘If you’re so uptight about it, all you are doing is proving the power of this medium that you cannot comprehend, and you fear your ignorance of this power’.

Has that general attitude towards fashion shifted?

Yes, somewhat. I’ve always said that fashion has this extraordinary power to both reflect and to project.

What is it reflecting right now?

You certainly see a lust for security in the couture collections we saw this summer. Everything was quite rigorous, stringent, monochrome, play-it-down, adopt a uniform, husband your resources – which seems like a response to the mood of the times. For all that power associated with couture, people haven’t really written about it in any consequential way.

Why do you think that is?

Because throughout history, it’s been about the 15-minute show. There’s no record, it’s gone. Think about Balenciaga couture shows – which I would imagine as being the apogee of design – and their equivalent in other fields. You wouldn’t get Le Corbusier parading his maquettes for 15 minutes in front of an audience. He’d just build a building that everyone would see forever more. Balenciaga would do his thing, and then it was gone; no photos, maybe just Bill Cunningham’s drawings or something.

That’s the transience of fashion.

That transience has interfered with fashion’s ability to be seen for what it really is: an extraordinary industry of creativity, and a testament to the human ability to transmute the basest things into things of searing beauty. It’s alchemy. But through its documentation in magazines like Vogue, it remains fashion. It’s not been documented in art magazines; there isn’t a fashion Cahiers du Cinema with mega-analyses of what we’re looking at.

‘Placing yourself in a group through clothing today is lifesaving: people don’t want to stand out as looking like a Muslim or a homosexual in the street.’

Has fashion always merited that kind of treatment?

Yes, always. From the beginning. But I guess clothes have always been a part of everybody’s lives, so it’s harder to sit back in wonder and say, ‘Oh my God, that’s an incredible feat’. Movies came late into the cultural mix – they were already considered an incredible technological feat – and the thing about the ephemerality of music is that you could recreate it; you could take sheet music and play the same thing in New York as people were hearing in Paris. But fashion shows never travelled.

Why not?

I’ve always said, ‘Take those McQueen or Galliano shows on the road!’ Let people witness them first-hand. It’s funny talking to Dries Van Noten, because the whole transience of fashion is exactly what enthrals him; he says the memory is what’s important. We’re not living in an age of memory; it’s an age of truncated attention spans.

Would you say we’re living in a particularly fashion-conscious era?

Clothing has always been about tribal identification. And identity has never been a bigger issue than now, because if you look at what people wear in the street, clothes have never been more boring. I remember on Fifth Avenue when people were wearing Claude Montana leather jackets, and now it’s all sweats and denim and marl grey. There has never been a time when placing yourself in a group through clothing is more lifesaving: people don’t want to stand out as looking like a Muslim or a homosexual in the street. Yet, conversely, there has never been a time when drag is more amazing.

Why is that?

Because it’s defiant. Its political point is honed every single day that Donald Trump is in the White House and Theresa May is in 10 Downing Street. The kind of fuck-you-ist vibe of drag is so mainstream now. What those kids do to themselves is staggering; it defies, it’s so beautiful. I just love it.

Where do you see that now?

I follow them all on Instagram; it’s utterly magical. Just as it was seeing images of Candy Darling in that other intensely troubled era of Vietnam and societal collapse. It had the same furiousness, even though we’re obviously post-50 years of gay activism.

What are your thoughts on fashion’s widespread embrace of social activism as a means to communicate?

This was an interesting season for that. Walter van Beirendonck is a designer who has always incorporated a lot of social comment into his collections, and he said that he didn’t feel good about designers suddenly finding their voices when they’ve always previously kept shtum. He feels that when activism becomes a marketing tool, it’s the time for wise old owls like him to shut up. That’s why he called his show Owls Whisper. Rick Owens said the same thing, and those two designers are more acutely aware of their environment than anyone.

What do you think?

If you are a caring and conscientious human being, how can you not express your opinions through what you do? And if it takes the incredibly dramatic events that have been endured over the last 12 months for you to find your voice, then at least you found it.

Do you think today’s consumers need to feel that fashion brands stand for something other than financial gain?

There is something I’ve read about – perish the word – millennials: that they are committed to the commitment of the people they make investments with. To me, this doesn’t seem new because I worked with Anita Roddick at The Body Shop for 10 years, and that was always the line – provoking people to ask questions. And, you know, big banks are investing in arms and then supporting Gay Pride.

How easy is it to get distracted by all the massive branding tools that fashion houses now have at their disposal? The advertising budgets, the brand ambassadors and celebrities, the social media, PR and marketing… Sometimes it feels like the collections are made into a success before they’ve even been presented.

I’m not distracted. Chanel is the perfect example of that whole D.W. Griffith approach to fashion.

How would you define that?

Just massive overwhelming spectacle that you feel pathetically grateful to be a part of. There have been Chanel shows that have been massive that I absolutely loved, and others that were equally massive that I didn’t really care for.

‘The Body Shop always provoked people to ask questions. Whereas these days, big banks are supporting Gay Pride while they also invest in arms.’

Spectacle for spectacle’s sake seems like an ever-increasing trend.

I think that fashion is generally quite good at adding some emotional clout to gigantism. It calls on things like desire and beauty; ideas that are distracting in themselves. This new thing of flying people off to remote corners of the globe for two days [to attend Cruise collections] is certainly an odd wrinkle. And it’s strange hearing people half-moaning, saying ‘Oh God, I’ve got to go to Kyoto next week’.

Do you think that fashion critics are unique in the world of criticism, because, for economic reasons, they cannot be genuinely critical?

You mean because they don’t want to bite the hand that feeds them freebies and trips to far-off lands? I’m not so sure the same situation hasn’t prevailed in other arenas with the wining and dining of opinion-makers. But it ultimately all comes back to the issue of what has constituted fashion criticism in the spotty history of fashion coverage. What has always been different with fashion is that ‘fashion criticism’ wasn’t the sort of thing that your average reader would curl up with, like a movie or a music critic in the daily paper. I felt it was more inside, more for the benefit of the industry. There was a lot of reporting, and then there were a few fearsome opinions that everyone looked to, and those writers were largely bound by traditional codes of journalistic integrity, which they still seem to be. No freebies. No junkets. No compromises. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t editorial partisanship. It’s human nature to play favourites, and it’s not hard to think of fashion examples. Getting back to your point about uncritical fashion critics, I’d say the ‘be-nice’ school of fashion coverage is something completely different. It’s an aside.

How easy is it for you to go to a show and remove any preconceptions of a designer or a house, and what they represent? Is the history of the house part of the criticism, or do you go there with a clean slate?

I try and make sure every moment has its own value, that there is a reason why I’m here. I will have all that historical stuff in my head – not in a wildly consequential way, but just because it’s all there. It’s hard for me to look at a John Galliano show and not remember the first one I ever saw. It would be wilful of me to block out the Lagerfeld or Gaultier or Prada shows that I’ve seen.

It’s hugely beneficial to have that knowledge stored away though.

It’s the texture for a review, and I guess I like to tell people about something that struck me maybe 20 or 30 years ago, without wanting to sound like a pontificating old bore. At the same time, all of that doesn’t make a bad thing good.

No, but it probably allows you to identify threads in a designer’s work.

You often find that there is a cyclical thing in their careers. Working on that Dries book [Dries Van Noten 1-100], it was funny to see what his tropes were over a hundred shows. You’re not so aware of the recurring Salvador Dalí references at the time, but if you go back, these quirky little themes do pop up incongruously over the years.

Fashion generally dismisses nostalgia. Someone like Karl Lagerfeld makes a thing of always saying, ‘Never look back, on to the next show’. Do you think that looking back is at odds with the very essence of fashion?

Fashion is surprisingly reflective and slow moving, for all its fresh-flesh syndrome. And it’s surprisingly ‘same old, same old’ a lot of the time. Considering the tsunami of blanket coverage that comes at you during the collections – Instagram, Snapchat and so on – I don’t think it’s nostalgic to say that a lot of the really important things that happened in fashion took place before all that existed.

Is that a shame?

Imagine if Instagram had existed for Galliano’s Dior show at the Opera Garnier at the end of the 1990s! Looking at that now in Alex Fury’s Dior book [Dior: The Collections, 1947-2017], I can barely believe those shows even happened. The clothes are incredible! The staging was Diaghilev-ien.

To Dries Van Noten’s point, don’t you think that one of the principal reasons those shows remain so incredible in your mind is because they weren’t documented so exponentially at the time?

That is what the designers would say. The transience is the allure. As Dries said, ‘It lives on in the imperfection of memory’. But how could you step back and change your mind about those things? I mean, they were utterly extraordinary!

‘I don’t think it’s nostalgic to say that a lot of the really important things that happened in fashion took place before Instagram and Snapchat existed.’

What other big moments from that time come to mind?

Walking into the McQueen show where there were these big metal drums filled with fire, and a terrible smell of burning and genuine sense of danger. Or that Gaultier show where this weird chemical shit was blasted at everyone to make it appear like a snowstorm. A whole bunch of people had to go to hospital afterwards because it got in their mouths. Thinking about those moments, I imagine it was like working in the silent movies before the movie industry went boom.

Why is there the general perception that fashion is so fast paced?

Because it’s seasonal. If you see something you like in a shop, then go back later to buy it, it’s already gone. A winter coat is hanging there instead of a bikini.

Was that an industry construct?

Yes. I think the industry created this demand that it now says it is satisfying with things like ‘see-now-buy-now’. If you look at Dior Couture or Balenciaga from the 1940s, it wasn’t presto changeo every season; it evolved gradually. If you wanted something from Spring 1943 in Fall 1945, I’m sure it was possible. I just think fashion got ahead of itself; I mean, there are clever people now, like Neil Barrett, who reintroduce things when the world is ready for them. Miuccia Prada does that very well, too.

You’ve written before that if you’ve bought something and you think it’s a little too much, put it away and bring it out again four seasons later. Based on today’s heightened sense of immediacy, does four seasons constitute vintage?

Well, what’s vintage? Is it the second something’s hung up with all the other old clothes? Designers like Gaultier never had archives, amazingly. Galliano paid his models in the clothes; there was no archive. And that was only 20 years ago. It’s like fashion never really took itself seriously.

Last time we spoke, you were describing how at shows in the 1980s the front row was where the photographers were placed. Which seems ironic today, given that every single person on the front row is now taking pictures.

They take pictures of the opposite front row. The big change is technology. People are looking at shows in a very different way.

Like live gigs, people aren’t watching fashion shows; they’re too busy documenting them.

Yes, and for what? I guess it’s an existential thing. ‘I exist. I am here.’ People can now prove that they exist, they can validate their existence through the phones.

Is that something you do?

I decided to take photos of the walk-outs because I thought it was useful, but it isn’t. I did one for Galliano and posted it. I haven’t posted anything on Instagram for a week; I haven’t even looked at it.

On the subject of immediacy, do you trust your immediate judgement when evaluating a show?

No, because sometimes you miss the thing that struck you the most. I take notes during the show, but, inevitably, when I send the review and I reread my notes, I will have forgotten the thing I most wanted to say. I remember talking to Cathy Horyn about this. Like, ‘Do you always have to start by writing the first paragraph?’ I’m much more likely to write the section that I feel gets to the essence of what I want to say, and then build the review around that. Especially if it’s late and I’m tired.

Given that you’re responding to a show very much in the moment, aren’t you keen to immediately assemble your notes into a review, and write it in the car on the way to the next show?

I know I should do that, but I’ve always managed to find excuses as to why I won’t: motion sickness, too dark to see my notes… I resisted writing on the iPhone for forever, but the Pages app is quite easy to use and I’ve got used to doing that a bit.

Are there habits, conditions, or rituals that precede writing?

What, like Truman Capote sharpening his pencils? [Jokingly] I have to clip my nails very short before I write. When I started doing reviewing properly for Men.Style, I was doing 12 shows a day, and writing all night. One thing that made the experience pleasurable was having a nice bottle of wine; it was like a treat, that would generally – but not always – keep me awake. Occasionally in Paris, I’d get a call at four in the morning from Tyler [Thoreson, the then-editor of Men.Style], saying, ‘We’re all here [in New York], waiting for your copy…’ And I’d be like, ‘Oops, I fell asleep!’

‘In Paris, I’d get a call at four in the morning from Style.com saying, ‘We’re all in New York waiting for your copy…’ And I’d be like, ‘Oops, I fell asleep!’’

Isn’t that anxiety-inducing?

Oh, I thrive off guilt and anxiety. That’s why I always let deadlines run away with me. I have discipline issues, and I don’t do anything about it; that’s part of the issue, obviously. I’m not disciplined enough to do anything about discipline issues. It’s like a Russian doll.

Do you get writer’s block?

Of course. Sometimes I can get it for days. I just try and write something that isn’t the piece I’m supposed to be working on.

Would you say that with writing, the more you do the easier it gets?

When I was doing Men.Style and then Style.com – both of them in a season – yes, the more I wrote, the more I wrote. Admittedly the reviews were much shorter a lot of the time, but there were days when I literally worked two days around the clock.

Has the squeeze of the deadline led you to write about a show in a way that you’ve later regretted?

Occasionally. There are times when I’ve said something glib for effect, and I get pissed off with myself because it’s such a cheap shot.

Is it easier to be amusingly nasty about a show rather than positive?

Without a doubt.

Can you be funny and positive?

Yes, but when you are being funny and positive you sometimes come across as just as much of an arsehole. Because it sounds like your positivity is a put-on.

Do you feel a responsibility to seek out at least one glimmer of positivity in any show?

I could sit through Zombie Biker Chicks in Lederhosen, or whatever it is that I watch at four in the morning, and think, ‘Somebody learned their lines and acted in this; somebody sat in an editing suite and actually crafted it’, and it seems like such a cheap shot to just dismissively give it an ‘F’.

Are there many fashion designer equivalents to z-movies?

There are some designers who just never evolved, never got better. In the end, I’d be thinking, ‘What can I even write about them?’ Maybe something that acknowledges their achievement with a nice description of what we saw.

Do critics consider being banned from a designer’s show as a badge of honour?

The problem is that it’s always the same people banning journalists. It’s never people who don’t ban them who suddenly start banning. Which would make more sense. It’s got to the point where enough people have been banned from one particular brand that they could all get together and, you know, have a big lunch while the show’s on. Like an alternative Miss World competition!

What about yourself?

I’ve not been banned; I’ve only ever been politely asked not to review. Unless I get banned from Dolce & Gabanna for the last review I wrote, because Stefano [Gabanna] got quite upset about it. Besides that, I had my Gaultier moment.

What was that?

It went on for quite a long time. He wrote a letter to me, saying that he was hurt about something I’d written, and that he thought we were friends. I wrote back, explaining why I thought what I’d written was valid. Cathy Horyn then called me from Charles de Gaulle and said, ‘Have you seen Women’s Wear Daily?’ He’d posted the letter online: an open letter to me, and made it meaner. The whole thing just went on and on for ages. I felt terrible because he is one of the greatest fashion designers who has ever worked. I don’t even want to dredge that whole episode up again.

What kind of things do you typically write about in your harsher reviews?

When people get stuck in a rut. Or, the gap between the ideal and the execution. You either temper your expectations of yourself, or not.

Is it a question of hypersensitivity, or defending one’s business?

That depends. I remember one time when a designer called me to say that all the buyers had cancelled their appointments.

As a direct consequence of the harsh review you’d written?

It wasn’t even me who’d written it. But I was nonetheless told: ‘You need to know this is what happens when journalists say the things they say.’

‘It’s got to the point where enough people have been banned from one particular brand that they could all get together and have lunch while the show’s on.’

And what was your reaction to that?

What can you say? I’m really sorry to hear that.

Do you take into consideration people’s livelihoods when you’re writing reviews?

Would you ever say anything ever again, if that was in your mind when you were writing?

Well, you’re just telling them in a harsh way to improve.

Unless they feel there is no need for them to get better. We’re living in the post-truth era and all that’s left is opinion. There is so much opinion in fashion and I’m not sure there are the voices left with the authority to make the power of opinion in fashion a life or death situation for a business. I think that words can wound savagely, but less so in the context of a fashion review than a take-down in the business pages.

Which brings us to your current employer. One very apparent thing about your show reviews is that you are responding to creative endeavours. Now that you’re writing these for The Business of Fashion, they exist within an editorial culture of business; the reporting of brands’ financial performances and so on. Do you think this affects the reading of them?

That’s a good point. For example, the site covers the recent business vicissitudes of Prada, and then there is my review that says, ‘Prada’s creative return to form’. But it’s possible for the site to have a variety of entry levels and points of view. I think Imran [Amed, The Business of Fashion founder] is very partial to opinion, and things clearly stated, and he and The Business of Fashion take positions on things.

It is almost unique in that respect.

Well, Business of Fashion has its own cross to bear because it has investors, so there is always that disclaimer about LVMH having invested in it. I don’t know why people automatically equate that with us being soft on LVMH because it’s obviously not the case.

One testament to the success and influence of The Business of Fashion is that I often find myself reading the early-morning newsletter – with its headlines like ‘The continuing downturn in sales’… ‘The end of American Retail’ – before I’ve even had breakfast. I imagine half the fashion industry clambers out of bed thinking, ‘We’re doomed’.

Don’t you find though that there are incredible stories about China and India that you wouldn’t have read before? I find myself reading those before anything else. The Business of Fashion has moved on from just who is up or down on the markets today, to embrace fashion as a human industry. It includes stories about workers agitating for their rights in Bangladesh, millions and millions of people trying to get by.

Are you part of the broader editorial decisions at The Business of Fashion?

No, I am a reporter. I suggest one or two things, but I’m not in the office, even though I live in London. I’ve always been ‘at large’… and getting larger.

Do you not crave human interaction?

No, I like isolation and solitude.

What about the audience?

It’s nice to be part of something that people are enthusiastic about. I get compliments for things that haven’t even been written by me. No one looks at the bylines. Considering my vintage and my lack of digital savvy, I’ve been extraordinarily lucky to be associated with Style.com, which was considered 2.0, and now The Business of Fashion, which is 3.0.

Since joining The Business of Fashion, do you take more into consideration the scale of business and the resources available when reviewing a brand’s show? Armani and, say, Grace Wales Bonner feel like they’re operating in two completely different industries?

Because one has deep pockets? Limited resources have always produced interesting results. The Velvet Underground recorded their first album in less than 24 hours. Raf Simons has wrung tears out of people with almost nothing. I don’t think there is an equation between limited resources and a great show. Obviously at the back end – or the bottom line – if resources are limited then yes, it’s tougher. But I think that Grace is an interesting case of someone who puts an enormous amount of thought into her shows, almost more than anyone. I mean, she gives you a reading list on your show seat! It’s fantastic. So, if someone with limitless resources does a mediocre show, I’d probably feel more critical.

‘Limited resources have always produced interesting results. Raf Simons has wrung tears out of people with almost nothing.’

How do you make the distinction between a good show and an exceptional one?

It’s not a rational process.

Do you leave shows thinking, ‘I’ve just seen something extraordinary’?

Maybe once or twice a season. I thought that last Craig Green show was exceptional – the best he’s done – and he’s a designer I’ve followed from the start. When he did that Children’s Crusade show – that’s what I called it anyway – people were in tears.

Do you see that happening very often?

No. I remember going to Geoffrey Beene shows at The Pierre [hotel] in New York and seeing Diana Vreeland and her gang weeping. And then actually going to shows where I could understand that response. Then my worry for a while was that Beene was a one-chord wonder, that what he was doing was fabulous but I could not see how it would evolve. And then it did.

Like what you said before: some designers evolve, and other don’t.

I’m sure there are people who have an extremely good business without evolving. But with Green, it was initially so new looking, you thought if he gives it a few seasons people will catch up. I began to worry that was it, but then it just jumped. There are instances – in my mind at least – where a designer makes that jump to the next level.

Could you give me an example of that?

That David Bowie Station to Station show that Dries van Noten did, or the Prada show with fur on bags, like big pelts.

Quite specific moments within shows.

Oh, I’ve been sitting in shows when halfway through there’s a chord change in the soundtrack, and – boom – the switch goes on and I’m like, ‘Whoa!’ Like when Jimmy Page played his guitar with a violin bow when I saw Led Zeppelin.

You referred to the Craig Green show as the ‘Children’s Crusade’ show. Do you care that your interpretation might be completely different to what the designer originally intended?

Not at all. I just think what I think. But I’m like that with the movies. I have a list of movies that no one else knows – and that are absolute schlock – but I could watch them 24 hours a day.

Do you get told by designers or PRs, ‘Tim, you know that thing you wrote, well it’s actually completely the opposite of our intention…’

No, they’re more likely to say: ‘Can we use your interpretation? We’re not going to write the press release until we’ve spoken to you.’

You could have such a malign influence!

I remember seeing one of Tom Ford’s Gucci shows and being struck by how it reminded me of those photos of Verushka in the desert, slightly tigress-y and wild. I think it was extremely flattering for a lot of designers to hear those kinds of associations. It was the first time most of them had been taken seriously.

You were placing them within the canon of culture that you responded to.

It was their culture, too. Like, I see Blade Runner a lot in shows. It’s funny because Raf made it so literal with that last show of his.

You must see a lot of Bowie, then.

I can see Bowie in a blade of grass! Although when I started out, there were far more old people around. If I was talking to Hubert de Givenchy, for example, he’d be too busy correcting my French pronunciation to even consider any of my references.

Who do you wish you’d have had a chance to interview before they died?

Cristóbal Balenciaga. But at dinner, because Cecil Beaton always said Balenciaga was very gossipy over dinner. He probably would have been gossiping about all those old society broads, who don’t actually interest me that much. I would like to have interviewed Richard Avedon, too.

Have you interviewed many other photographers?

I remember once interviewing Horst [P. Horst]. We had such a good time. He must have been in his 80s and he was very funny. He lived with his minder in Toronto, and at one point the minder guy went to the toilet and Horst quickly smoked a cigarette and was like, [whispering] ‘Don’t tell him!’ He then said, ‘I would love you to come and stay at Oyster Bay’, and in my head, I was thinking, ‘I bet you say that to all the boys’. I mentioned it to someone later, saying, ‘It was so sweet because Horst asked me to go stay with him’, and they said, ‘I hope you did, because he never ever asks people over to stay, so if he did ask you, he would have been so insulted that you didn’t go’. And I was like, [groans] ‘Oh, great!’

‘Horst P. Horst then said to me, ‘I would love you to come and stay at Oyster Bay’, and in my head, I was thinking, ‘I bet you say that to all the boys.’’

Who would you like to interview who is still living? Someone who you haven’t had a chance to properly speak to?

I have never interviewed Azzedine, and I love what he does. I would really love the opportunity to go deep with him, because a 300-word review written an hour after the show just isn’t that. Well, some of my reviews go really long. Maybe the longest one I write might be 600 words. I have to save myself from getting stuck at 150 words and thinking, ‘Oh God, I have to go back and add a load of words.’

This piece is probably going to end up over 10,000-words long.

Wow. Really?

Can you think of a piece of fashion journalism that you’ve read in the last, say, 12 months that’s impressed you?

Matthew Schneier’s piece in the New York Times about Ben Cho – the New York designer who killed himself – was amazing.

Which designer, who for whatever reason, disappeared from fashion, is due some kind of revival or renaissance? Who do you miss the most?

Christian Lacroix. I don’t know if you could bring him back, but he is an absolute genius and a wonderful man.

Have you ever done an interview when you’ve accidentally forgotten to press record?

Yes, loads.

Who?

Rei Kawakubo.

Part Four

Quantity has bred

an appreciation of quality

What is the most significant change in fashion that you have observed over your time of working in it?

The rise of digital coverage. When video first came along, people started to ‘do’ fashion shows instead of just having the girls walk back and forth. My producers at Fashion File loved things like Betsey Johnson – it was great for TV – whereas Helmut Lang looked a bit sterile on the screen for anyone who didn’t know about fashion. The biggest change brought about by the digital rise is the popularizing of fashion. How it’s gone from the time I started – you know, the very first couture show I went to, which was skinny-ankled ladies on tiny gold chairs at Saint Laurent – to this sort of frenzy of spectacular shows and social-media coverage, and the star systems that have evolved with that.

Is it going to continue getting bigger and bolder and more spectacular?

I think everything is escalating like that. I mean, when a Pirates of the Caribbean movie costs $250 million and is, in my opinion, total dreck, what’s the point? Then you thank God for things like Moonlight. I do feel it is like a hothouse effect and we are heading towards a cliff.

The level of choice we now have as consumers of fashion is remarkable, too. To the discerning eye, are the hundreds of different fashion brands available on Net-A-Porter simply too many?

Of course. You can’t see the forest for the trees. But what’s interesting is that it puts the onus back on the customer, and credits them with the ability to edit. Obviously, no one in the world – except perhaps [mentions a celebrity] – is going to order from every single one of those brands. So, what do you do? You scan down the list until you see a name that you recognize.

Is this era defined by a sense of quantity over quality?

No. The quantity has bred an appreciation of quality, in everything. People are reading beautifully designed and crafted books again. Quantity drives people back to things that make them feel good. The Business of Fashion did that funny little story about florists and fashion, and Cathy Horyn did one too, about small, artisanal practices. Someone recently posted the cover of Schumacher’s Small Is Beautiful49 on Instagram, and I remember when people were reading that 25 years ago in the face of what they thought was corporate overwhelming-ness then.

It seems that today’s winners are those that marry the facade of the artisanal with the multinational corporate structure and resources, like Apple.

Gucci is an extraordinary example of a business that places a macrocosmic scale on a microcosmic vision.

‘When you give people the choice, they’ll completely fuck you up: they’ll vote for Trump; they’ll vote for Brexit; and they’ll buy a crazy Gucci jacket!’

Micro- because its sheer nicheness shouldn’t appeal to the masses?

Just the crazy idiosyncrasy! It is so nuts. If it is aspirational, then it’s a redefinition of aspirational. Jared Leto on stage, in the clothes he is wearing, like crazy wizard coats and stuff – it’s like wow! Gucci is the nutty hippy sitting on the beach embroidering jeans for his friends, but done on a huge scale. It’s completely rewritten the rule books.

Are you surprised by the success?