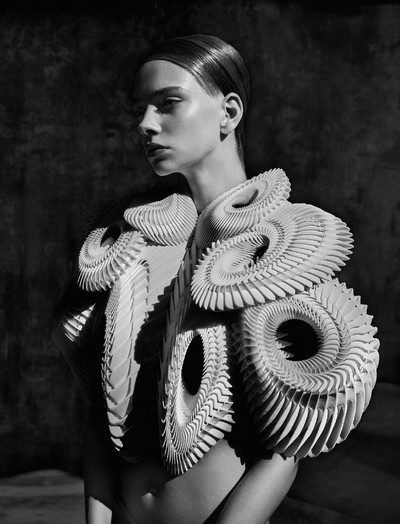

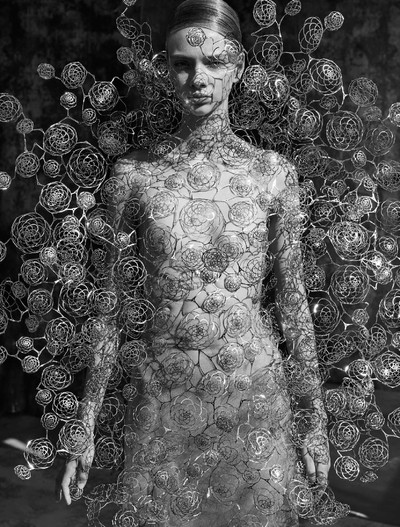

Iris van Herpen on 10 years of pushing the boundaries by fusing fashion and technology.

Interview by Ariane Koek

Photographs by Sølve Sundsbø

Creative Direction and Styling by Jerry Stafford

Iris van Herpen on 10 years of pushing the boundaries by fusing fashion and technology.

Since launching her label in 2007, Iris van Herpen has earned a reputation as an avant-garde technologist, pushing the boundaries of form and couture technique. Experimenting with previously unexplored methods, van Herpen has challenged the conventions of haute couture, marrying its time-honoured traditions – the meticulous handwork of the petites mains – with modern machinery, such as 3-D printing.

Admitted as a guest member of the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture in 2011, van Herpen has since presented a number of collections made in collaborations with scientists, artists and architects. She has played on perspective with 3-D printed paillettes made with abstract artist Esther Stocker; shown injection-moulded silicone that ripples across the skin to a soundtrack played by underwater musicians; and used iron filings manipulated by a magnetic field for a collection inspired by a visit to CERN, or the European Organization for Nuclear Research.

It was there in 2014 that van Herpen first met Ariane Koek. An expert in arts, science and technology, Koek founded the laboratory’s Collide Artist Residency Awards to make seemingly impossible links between the arts and scientific practice. Koek and CERN’s work continues to inspire van Herpen’s designs, both technically and aesthetically. Alongside pieces constructed using magnetic processes, quantum foam – the idea that the fabric of the universe is a foam-like mass of time-space bubbles – inspired a collection made of thousands of hand-blown glass bubbles that form a foam-like exoskeleton around the wearer’s body.

This is van Herpen’s sui generis approach to integrating science and technology in her work, unlike anything previously presented in a haute-couture context. The seemingly immiscible elements of printing, metalwork, synthetic fabrics, and nature references come together with a poetry that does little to give away the complexity of her research and construction process. It is why her work has been collected by cultural institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as well as academic institutions such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

System brought together Ariane Koek and Iris van Herpen to discuss the designer’s idiosyncratic, multi-disciplinary approach, her of 10 years of haute couture, and the practicalities of sustaining her innovative work.

‘I saw architects in Amsterdam working with 3D printers and was taken by how precise they were, and how much potential there was to produce clothes.’

Ariane Koek: So, here we are in your studio, surrounded by 10 years of work. I suppose we ought to start at the very beginning. How did you choose to go into fashion?

Iris van Herpen: I come from a really small village, so fashion wasn’t something I was that aware of. There was nothing on television; there were no magazines. But I moved to a high school in a small city, where I got to experience more about clothes and identity – style, rather than fashion. I didn’t really know how to do it, but started making clothes at that time, around the age of 12 or 13. I didn’t have a sewing machine, so I’d sew everything myself, and time really starts to slow when you’re sewing by hand. It felt like mediation, my own time and space. I hadn’t experienced it with anything like that before, so I’d take every moment I could to make something. I knew I wanted to go to the art school; I just didn’t know if I wanted to go into fashion, sculpture or painting, because they were all quite tactile. But I realized that with fashion I could sculpt and paint, too. It was the perfect way for me to focus on the body, and work with my hands, and bring together everything I enjoyed.

I expect that while you were studying at ArtEZ University of the Arts [in Arnhem, the Netherlands], there wasn’t much access to the tools and techniques you’re known for using today. How did you discover those?

At art school, I actually preferred handwork to the sewing machine – which was a disaster at the time because they told us we weren’t allowed to do handwork in final year. I could barely use a sewing machine! I think the reason for that is probably because craftsmanship and handwork is not an industry. I don’t think they thought it was a good plan to have people so focused on craft…

When did you first look to technology as a tool for the creative process?

I realized I had ideas that I couldn’t really produce by hand, and I saw that architects in Amsterdam and the Netherlands were working with 3D printers. I was really taken by how precise they were, and how much potential there was to produce clothes. So I started working with an architect because I didn’t have the experience, and had no idea how to create files for the printers to work from. That was definitely when I realized the potential of combining that kind of technology with fashion.

Can you remember the first collection you did using 3D printing?

It was a collection called Crystallisation in 2010. I started working with Daniel Widrig, a London-based architect, but at the time it was more like a side-project, an experiment. But before that, I was working with two architects who had designed a museum in Amsterdam and then asked me to make a dress inspired by their museum. It looks like a big bath, so I decided to make the water element that was missing in the architecture, and that was the turning point. You absolutely cannot create water with a needle. So that’s how I started thinking about 3D printing. But actually, at the time, water was impossible to make with a 3D printer, too! So, I did end up doing that by hand, but the project made me aware of the limits of handwork, and I realized I wanted to find more ways to create. That’s why I became so open to collaborations with architects: I was learning about the difficulties and the possibilities of the technique. I think almost half of my collection shown in Paris was 3D printed after that.

How have your experiences working within fashion informed that creative process? You went from studying to working with Alexander McQueen, didn’t you?

Yes, it was my first internship. He really inspired me. I mostly did handwork, and pattern-cutting there, but I learned a lot about working with fragile and difficult materials, and of course, McQueen’s pattern cutting was famously precise. I learned a lot about the process of working towards a collection and a show, and the research that goes into that, creatively as well as practically. I think I just learned a lot about fashion: what it takes to create a collection, how one collection relates to the next. Little bits of everything.

Straight after that though, I worked with Claudy Jongstra, who isn’t connected to fashion at all, but to art and architecture. I got to be much more involved in working on the concept and experimenting with process with her, and when she had new things to develop for buildings, I’d start testing materials. So I think with both experiences, getting to work across fashion and art, I had all the elements: development and craft. I enjoyed both.

You must experience a lot of failures though, just in the sense that your work with material is so experimental.

It’s a big part of my work, especially in the material development. That’s all trial and error. But sometimes a material seems to have failed, but actually turns out to be fine in the end. Draping, however, is another challenge. After material development, the draping starts. I don’t draw. The little drawings you get at the show, they’re done by someone else…

‘It’s frightening to imagine having a job where I would be able to look 15 years ahead. I prefer not knowing what happens next month.’

I think some people would be surprised about draping, as the word implies working with fluid fabrics, not metal or 3D-printed materials.

We never finish a piece before it’s been seen on a real, moving body, and we understand the interaction between both. So we can get a sense of how the piece moves, sometimes I’ll drape it on myself. The draping and re-draping is something that really connects to my early interaction with clothes though, connected to handcraft. That’s the part that really inspires me creatively. It is a long process; it can take anything between a few hours and several weeks, but I think it’s the part of the whole process that I enjoy most.

What made you decide to go it alone and start your own label?

The freedom of fashion, and fashion feeling like self-expression for me. That’s crucial. But also, during my early internships, I definitely realized that parts of me weren’t in use. I just get really restless when I can’t express ideas, or find an outlet for things I have in my mind. I just need to get them out. So it wasn’t a business-driven decision, like, ‘Oh, I’m going to start my own company with a 10-year business plan’. It was very intuitive and more about, ‘Let’s see where it goes’. But I like that – I’m happy with risks. It’s difficult to imagine having a job where I would be able to look 15 years ahead though; I think that would frighten me more. I prefer not knowing what happens next month. That sounds strange, maybe. But even in the process of making a collection, if I started on a collection with ideas, knowing how it would all turn out in the end, why would I make it? I don’t see the purpose of that. I need the unknown; I think the unknown is my energy in that sense.

But practically, Iris van Herpen is still a company with a workspace and staff you have to pay for, and of course, you need to earn a living. When you launched ready-to-wear in 2014, was that a business-driven decision?

It was stimulated by expanding in that sense. I think it was a good step in that we did communicate to a wider audience, which was definitely the goal – as well as create pieces for them. At that time, after winning the ANDAM Award, launching ready-to-wear, it felt that there was no other way than to go with the system.

Why did you then make the decision to spend less time on ready-to-wear?

For me, fashion – clothes – is about quality and not quantity. There is so much speed, so many imitations in that system, so I had to reduce the quality. I could produce ready-to-wear for the rest of my life, but it’s not what is going to make me happy, and it’s not what I want to say in fashion. There’s way too much of everything already, and I don’t really need to make another T-shirt and add to that. Of course, as a business decision, it’s obvious, but it’s just not for me. I feel like we can do more interesting things, and maybe that’s the harder, but different way. It’s what makes me happiest, and it’s where I feel I can add something to the system. Couture is more sustainable in that sense. I still believe in developing my work as a form of art, and it’s important for me to focus on couture because couture is the part of fashion where we can push things.

… and fashion moves so fast now.

I like the speed of fashion; it’s not something that I’m against. For me, that pace is a good stimulant to keep moving forward. The rhythm is tough, but it’s good. I think I’ve found what feels like a happy balance, being able to spend six months on maybe 18 pieces. If I had to make four collections a year, I’m sure the development and innovation, and the quality would be different. I think it’s a case of thinking how much you want to make while working within the system and its established model. Having two collections a year, loosely working within that schedule, deciding how much we can make, that works for me.

So what about other elements of that system? What role do press and marketing play within your business?

I think it plays a big role. There’s definitely a lot to explain considering there’s so much technology involved, but I’ve felt that change over time. The press seem to understand my work more now, and also I think generally the press are less focused on fashion now. Any interviews I do – and read – seem quite broad now, which I enjoy more.

‘Ready-to-wear is not what I want to say in fashion. There’s too much of everything already, and I don’t need to make another T-shirt and add to that.’

You have a collaboration coming up with Sasha Waltz, and you’ve also collaborated with Benjamin Millepied. So you’ve been moving very much toward dance. Are there any other art forms or disciplines that you want to engage with?

I am working on a project in architecture. Of course, I’ve worked with architects before for my own work, but now it’s the other way round: I’m now helping architects with the design of a building. That’s a very big, very new step. It’s nice to turn inspiration into creation in that way. Architecture has always been a huge source of inspiration for me, so being able to create as part of that world is challenging, but exciting.

How about technologies that you haven’t yet worked with, but would like to explore?

I’m doing quite a lot of research into 4D printing. At the moment, the technology isn’t quite there for me to use yet; it’s still too new, but I am very excited about the idea of working with it. With 4D printing you can sort of design a different movement to what the material would naturally do. So it is almost like designing evolution. You’re changing the shape, structure, colour, whatever you can think about.

And are there any technologies you’re looking at beyond printing? Are you interested in the technological development of fabric and materiality?

The space between materiality and immateriality is very interesting. But I am more interested in the space between, thinking about what isn’t there but could be, rather than immateriality itself as something like virtual reality does. Those disciplines, I think they’re great PR, but I don’t feel inspired by or excited by them. I think materials will change a lot in years to come, and I am very curious to know where it will go, because so much of our lives are immaterial at the moment. To me, that makes materiality so much more important. Maybe that is a counter-reaction. You see something online that you can’t touch, so maybe that’s an interesting thing to explore. I wonder how technology will develop to communicate a more complete experience of materiality. It is definitely trying to. I mean, the experience of seeing someone sitting next to you is such a different experience to seeing that person on Skype. Also, I don’t know if this is going to be sooner or later, but I do think materials will be grown in the future – for everything, everyday use, architecture and fashion. It addresses the whole concept of waste, so a lot of companies are starting to develop materials that can be grown, and I’m curious to see where that will go.

You’re obviously very into science. You came to visit us at CERN, for example, and talked about the notion of genetics in your work.

I am fascinated and perhaps even a little scared by the possibilities of where technology and biology come together and fuse. It’s an interest – and a fear I suppose – that I don’t directly translate into my work, but it does fascinate me. I have no idea where it will go, and maybe the unknown keeps me interested. It’s also connected to philosophy, because it’s not about what we can think of, but what we can do with the things we create. I’m curious about the decisions we’ll make, bearing in mind the possibilities of what we are creating. Art and science are the most powerful media of transformation, and I think that’s why they both stay in my mind. I’m driven by the thought of where both will take us.

So if you were to look way ahead into the future, the 22nd century, and imagine how they might describe you, what do you think they’d say?

That’s a big question! I think, or I hope, that my work can be seen in a number of ways. When I look back at my work over the years, I think that most of the things I learned in the early years, I’ve let go of now. So, in that sense, I’d love to be thought of as always moving, maybe always looking for disruption to go further. I’m very much looking at the possibilities within fashion, and that’s something I’d like to be recognized for – but I’ve never thought about that before!

So would you say you’re a fashion designer?

You want one word or one title? Oh yes, then a fashion designer. But that shows the scope in what fashion is to me. I also think, that people are much more collaborative today. If we think about a fashion designer today, we have a very specific idea of what that is, and that’s a person who is designing with fabric, making garments. I think, and hope, that disciplines will become much less fixed in terms of what we understand them to be, and interact much more.

How do you get people from other different disciplines on board? Is fashion a hard-sell to those in other industries?

In general, those people aren’t so interested in fashion, so I think they come on board because they see I’m already collaborating with other disciplines. They maybe see a new possibility, and that might trigger them to think about fashion in a different way, to see new possibilities. That’s the impression I get when I start working with someone from a completely different background. I’m happy that those seemingly impossible links are made.

You’ve dressed some pretty extraordinary people, too – Björk, Tilda Swinton, Beyoncé.

Björk did a DJ set at our 10th anniversary celebration. That was a moment. Meeting her for the first time was special. As a high-school kid, I grew up with her music, so being able to make my work, which feels so personal, for her, that was special. It’s a strange feeling, like a moment that makes you pause and think about the point you’re at.

… and what point do you feel you’re at, 10 years in?

I feel that I’ve touched base with a lot of things, but I feel that it is very much touching bases, rather than diving into all those subjects. So, perhaps that’s next: a deeper exploration of the things I’ve touched upon.

Do you feel a part of the wider fashion industry?

Yes and no. I’ve created my own family within the system, but the fashion system is so big. I feel really connected to the people I know within it, and that’s how I feel as if my work is alive. But I don’t feel part of the general system as a whole, because it’s too big. So I’ve created my own niche within it.

Photography assistants: Peter Carter, Kai Cem Narin, Simon McGuigan. Models: Elza at IMG, Nadine at Elite, Kyona at Elite. Casting director: Madeleine Østile. Hair: Martin Cullen at Streeters. Hair assistant: Reuben Wood.

Make-up: Sam Bryant at Bryant Artists. Make-up assistant: Elise Priestley. Nails by Chisato Yamamoto at David Artists. Set-design: Robbie Doig at Dragonfly Scenery. Digital tech: Lucie Byatt. Film assistant: Samuel Stephenson.

Production: Sally Dawson, Elise De Rudder, Paula Ekenger. Special thanks: Annemiek at Art + Commerce, Pauline Bianchi, Emma van de Merwe.