Reinventing Hermès, by the trio behind the pivotal campaigns photographed by Bill King.

By Thomas Lenthal

Reinventing Hermès, by the trio behind the pivotal campaigns photographed by Bill King.

Few brands operate at a scale like Hermès, yet still manage to retain such a sense of discreet luxury. Despite over 300 stores worldwide, the 180-year-old house continues to whisper, rather than shout, with an understated approach to both design and marketing. Its choices of designers since the late 1990s have only reinforced that, with the famously reticent Martin Margiela designing womenswear, followed by the equally reserved Christophe Lemaire and Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski since then. (Jean Paul Gaultier’s reign being the exception that proves the rule.)

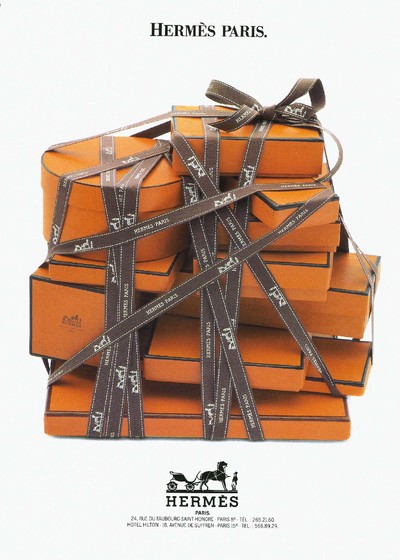

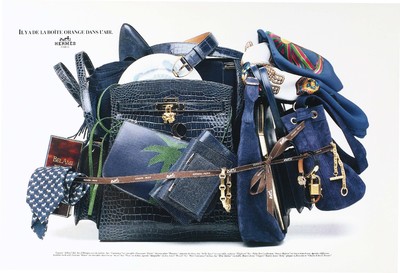

This discretion is almost paradoxically accompanied by the house’s instantly recognizable design signifiers: the bold orange packaging, the collier de chien buckle fastening (a feature of the handbag carried and named after the late Grace Kelly), horse-bit prints and silk carré scarves. If these motifs are now seen as indissociable from the brand’s core identity, it is thanks to the campaigns created for the house by ad agency Eldorado, now known as Publicis EtNous, since the 1970s.

Founded by Françoise Aron, Pacha Bensimon and Bruno Suter in 1976, Eldorado took a bold approach to its work with Hermès, helped by the free hand they were given by the house’s chairman Jean-Louis Dumas1. Working in tandem, he set about transforming the family-run house’s commercial and financial strategy, while the trio’s communications work successfully reinvigorated its fusty image with a new sense of dynamism.

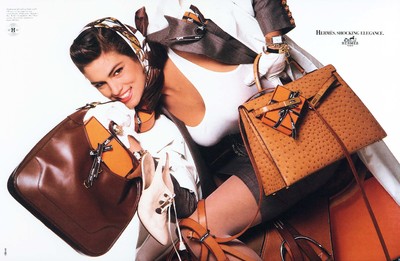

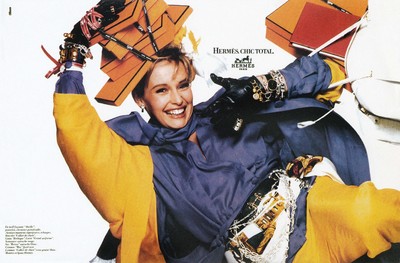

Much of this exuberance was supplied by photographer Bill King, whose high-energy images of the supermodel era were regular features of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue in the mid-1980s, until his death from AIDS in 1987. Aron, Bensimon and Suter were among the first to commission King in Europe, and the work they did together – showcased on the following pages – brought they all brought new joie de vivre to Hermès, while introducing it to a new, younger audience. System met the Eldorado three, to discuss the importance of being trusted by your boss and having confidence in your photographers, and the changes in marketing luxury brands since the 1970s.

‘Someone at Hermès said to us, ‘Just don’t talk about the scarf, it’s the least fashionable thing on earth!’ So that’s exactly what we did.’

Thomas Lenthal: Tell me how you all met.

Françoise Aron: We met at Publicis, where I was working as an account manager, and Pacha was the creative on all the campaigns. Bruno joined us two or three years later.

Bruno Suter: After two years, we worked a lot together, then Françoise and I decided to set up our own agency, so we did. Then we said to ourselves we need someone else, and that was when Pacha joined us. That’s a quick version of the story.

Pacha Bensimon: That was in… 1976. It was kind of exceptional because we felt this strength together, and we knew it was the beginning of an agency: Eldorado… in the depths of Neuilly-sur-Seine!

And you didn’t have the Hermès account at this stage?

Françoise: No, not then. We didn’t have anything with Hermès. Jean-Louis Dumas had been aware of what Eldorado was doing, and we knew each other as we were former schoolmates. So when his father died, and he became chairman at Hermès, he called and said, ‘I’d like you do something for us. We don’t have much money, but would that interest you?’ We weren’t going to say no! Jean-Louis had total confidence in us, and with that confidence came a freedom to do exactly what we wanted.

Pacha: There were no briefs, just, ‘OK, so we’ll do an image with Hermès shoes…’

Françoise: When shoes were zero percent of the turnover. But we all agreed that with an image of shoes… well, you can say everything about Hermès with shoes: the shoes with the squared-off toe, the shoes in green ostrich skin, the two-tone shoes. We took all of those and worked with them.

Was that the first campaign?

Françoise: No, the first campaign was the girl in denim. It’s very important. That one, we did in 1978.

Pacha: What started our way of thinking, and how we worked was when someone at Hermès said to us, ‘Just don’t talk about the scarf; it’s the least fashionable thing on earth!’ So that’s exactly what we did. Which of course boosted the scarves like nothing before. We knew we wouldn’t change the products, they were then what they are today: the scarves, the Birkins, the Kelly bags, the gold chains. What we wanted to do was change the impression people had of this institution, so, we said, ‘Right, what we have to do is change the way people view Hermès’.

Françoise: This was the first time that advertising clashed, or I suppose, was considered, with everything else. No luxury brands were really considering advertising and marketing at this time.

That’s what I thought – luxury brands weren’t actually advertising then. Not in the way they do now. It was considered vulgar.

Françoise: Even Jean-Louis was reticent, but he had this incredible instinct for his house. That was why he had complete confidence in us. So we worked beyond the standard codes, and we started with objects; we showed luxury products in a way no one had thought of doing before.

Where did the idea of wrapping up come from?

Bruno: That was me. When I saw those things, the boxes… all so wrapped up, with the ribbons. I had that in mind. That was my guide, that being the signature and all that. They even did a Hermès scarf with the ribbon after that. It was orange with the ribbon above it, over a box. Sorry for showing off a little bit, but that was my idea. I was quite obsessed with it. It was funny.

Françoise: Bruno was amazing with his Swiss, mountain-minded instinct, because he completely grasped that the wrapping and boxes were vehicles for fabulous advertising.

‘No luxury brands were considering advertising at this time. We showed luxury products in a way no one had thought of doing before.’

And so that was a huge success.

Pacha: Huge, with the sales figures, too. Sales of the scarves skyrocketed the following Christmas. The demand for those silk carrés was enormous. At one point, we did have to bring in the clothes. No one chose for us though.

Françoise:The brief was like, ‘What about the clothes?’ The denim had just been an accompaniment to the scarf. But then – and this seems amazing today – as Bruno said with the ribbon design, we had some influence on the products. Jean-Louis said one day, ‘We’re launching a new bag. It would be good if you could do something for it’. It was in burgundy though, so I said to Jean-Louis: ‘Sure, no problem, but not in burgundy! We want something amazing, real colours.’

Pacha: So, he made it in green, and then that led to a whole load of other small leather goods. We then said, ‘OK, you should do it in crocodile’. After one advert, they sold 17 bags.

At €50,000 a time just for one handbag… Who was the stylist working on those campaigns?

Pacha: There wasn’t one. It was just us and [photographer] Daniel Aron. We chose the scarves we wanted to work with. I remember doing the styling for an image we did in Venice. Our girl didn’t have any clothes, so we used the dressing gown from the hotel. People wouldn’t believe it – these days you do a shoot with an entourage of 30 people. There was so much fog, we were worried about getting lost. There wasn’t a make-up artist either – nothing, and no retouching!

Françoise: We always chose the emblematic garments, clothes inspired by the scarves, for the campaigns. To change the point of view we used girls who became top models: Estelle Lefébure, Cindy Crawford, Paulina Porizkova… it was uplifting.

Who chose Bill King to photograph them?

Bruno: I found him. I thought he was interesting because he brought something new; there was a freshness and gaiety in his pictures. I wanted him to do Bill King; we had to let him do his thing. When we started working in fashion it was important to escape a little bit, and at the same time there were new designers at Hermès, so it was pretty new back then.

Pacha: Bill liked the idea of the brand, and he came to Paris to do the campaigns for a now defunct brand, Harriet Hubbard Ayer. Then, when we started doing the ads for clothes at Hermès, we thought of Bill again. The first campaign we did with him was in New York. So, we stuffed our suitcases full of Hermès, because our idea was to do a sort of over-representation. We decided to play with the idea of accumulation – outrageousness – so belts, boots… This was obviously the 1980s.

…a time of excess. How many of you went to New York?

Bruno: Oh là là, only two! We went on our own; sometimes it was only me who went. Just me and a suitcase. Bill would organize the stylists and all that. But for big things I would go with a stylist who was often Melka Tréanton, sometimes Carlyne Cerf de Dudzeele – I can’t really recall who worked on what when. The make-up and hair were all there.

Was it Bill who did the casting?

Françoise: Yes, it was Bill. He found Estelle, Cindy, and all the others. We didn’t even see their comp cards. He’d just say we’ve got so and so.

Bruno: Cindy was already well-known. But she was paid normally then; she wasn’t a star.

How did Bill make the girls move? Was there music?

Bruno: Oh no, there was nothing at all. It was calm, and when you went in, there was a large panel, and everything was so clean.

So how did he transmit that dynamism to the models?

Bruno: I think it’s because he was the quickest guy I knew; the flashes were continuous; he just shot photo after photo. He got them moving with very little, but the models knew exactly what he wanted. There were never any static photos. Everyone got moving, even the assistants, and it was like everything was on wheels, like a photo factory, it was crazy. He shot non-stop, like a crazy person.

When you look at the images you get the impression that the people are just about to fall, it’s pretty amazing.

Bruno: Yes exactly, he always caught the perfect moment, and I think he knew when that right moment was. Well, the proof is there with everything he did; it’s sublime. I don’t know who this was for, maybe Harper’s Bazaar, but there was a shoot with a baby who was maybe six months old, and the expression on the baby’s face is quite exceptional. And that’s what made him one of the greatest photographers. Also, what was also exceptional for the time was the selection process. The photos still had to be developed back then, so Bill would take the photos, then they’d be taken by a courier to be developed. The edit was made with him while I was there – we all worked so closely together. I have to tell you about the way Bill chose the photos. All the photos would be spread out over a table and within one minute he would have made his choice with a cross on what he wanted. It was concrete in an instant. It was so professional; it was incredible.

Did Bill King have much of a reputation in Europe at the time? It’s funny that there are no books on him, no exhibitions, nothing.

Bruno: That’s amazing because he was working for the biggest magazines in the world at the time, Harper’s Bazaar and so on. He was known for that; that was how I discovered him. At the time, it really was him and Avedon, they were the two who really counted. Bill was doing his thing with white backgrounds.

‘It was like a photo factory, Bill King shot non-stop like a crazy person. I think he was the quickest guy I knew; the flashes were continuous.’

He’s probably the biggest photographer who used white backgrounds.

Bruno: Of course, and using so little, there was absolutely nothing else. Some photographers take hours to set-up, but with Bill, once the people were made up, we’d start shooting. Working with him was incredibly simple. He was absolutely incredible in terms of speed. When we were preparing the photos, between the models and all that, it was so easy. There were never any problems.

Françoise: He had a formula; the same way of working each time. With him, people really let go, and became joyous and free. He had an incredible joie de vivre. He was very elegant too, always in jeans with a polo shirt and loafers, and a crocodile-skin belt.

And Jean-Louis in all this, when you told him you were going to shoot with Bill King because he’s upbeat and fun, what did he think?

Françoise: He trusted us, so we had meetings with him, but they weren’t briefs. He had a way of talking to us that wasn’t like a brief at all. We’d talk about so many things, so many digressions, talking about people we’d met, etc.

Bruno: We could never have done it, the agency, without Jean-Louis Dumas. There was no one contradicting us, and when Jean-Louis said yes, it was good. It was so simple. I just can’t tell you how simple it was.

Pacha: We started working with Hermès just as it was being reborn with Jean-Louis, and we saw things as he did. He was fresh, innocent, clever and kind. That whimsical aspect of Hermès, that was what we knew him for. That cheeky side, that was him and that was what we translated – that sort of innocent joyousness and daring. One day they launched an orange-coloured leather and we said, ‘Great, let’s do an advert’. So we did. Spontaneously, just like that.

Françoise: We never struggled; never showed any mock-ups or sketches. We retained the spontaneity with a serious dose of improvisation. We didn’t get anything validated.

When the photos were done and you made your choice, one image per advert with the text, Jean Louis would just look at it and say, ‘Yes, great thank you’.

Pacha: Yes, that’s exactly how it was.

When you think about the last 40 years, how much has changed? I’m not talking about the project briefs or conditions, but how has your take on the house evolved? When you think of Hermès, do you still think of Jean-Louis?

Pacha: We think about Jean-Louis. He is very present in our minds, and we still say, ‘Oh yes, he’d like that’ or perhaps wouldn’t. We’re both very critical of our own work though. We get called the ‘Tatas Flingueuses’ – Axel [Dumas, Jean-Louis Dumas’s nephew, who took over as chief executive in 2011] calls us that. I think it’s quite chic.

It’s untranslatable in English.

Pacha: It’s because we say what we think. Well, we say what we think, but we’re a bit more delicate now. We wear gloves more often – fur-lined gloves from Hermès!

Unlike most luxury brands, Hermès works with this idea of the committee, with always at least 15 people around the table. Does there have to be consensus?

Pacha: When we did all those campaigns, Hermès was a company of 7,000 people. Today, there are 12,000… Before, we used to choose things from the catwalk shows, and we’d say that’s nice or that could be a good theme. To be honest, now, if we want to change a product it’s certainly not as easy as before.

Françoise: The girls in denim, which everyone still talks about, we probably couldn’t do that today. Now, when you take an item of clothing, you’re almost obliged to take the whole look number 15 from the show, and with that look comes the shoes, the bracelets. What we always did was mix up the pieces. That’s where the girl in denim comes from.

Has your perception of the luxury market changed?

Pacha: Luxury used to be little artisanal companies just like Hermès, and now they are all multinationals backed by huge financial groups. That is what’s changed. When we did those early campaigns, there was the house of Chanel, which hadn’t taken off really, and Dior – they were little French houses, and now they are vast multinationals. That’s what upset everything.

Was choosing to work with an American photographer ever an issue? Because there were some good photographers in France in the early days, and it was a French fashion house… but you chose Bill King.

Françoise: We did a campaign with Avedon, too, six months before he died. He was amazing. I remember, he was so excited about a shot. He was so young, nothing was fast enough. He was so overexcited with the girls; I couldn’t believe my eyes. But, no, going back to working with American photographers, that wasn’t an issue. Jean-Louis had exceptional taste, and geography didn’t have anything to do with that.

…and Bill’s work was so optimistic, so fresh.