The enduring influence of Jil Sander.

By Ingeborg Harms

Photographs by Norbert Schoerner

Jil Sander has – perhaps for the first time in her life – been looking back. A major retrospective exhibition of her work, opening in November at the Museum Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt, has provided her the context in which to re-examine an extraordinary 50-year career. One that has given the world a legendary fashion brand, but also a design philosophy combining rigour and natural elegance, which Jil Sander herself often refers to as ‘pure’.

Her introspective mood ahead of the exhibition felt like a unique opportunity for System to ask Jil Sander to discuss her singular aesthetic approach, and to examine why its influence is now being felt more widely than ever.

So we brought Jil Sander together with Joe McKenna, master stylist and long-time collaborator, to discuss looking backwards and forwards, individuality and teamwork, and the realities of life, in and out of fashion. Sander then asked System to talk to sound artist Frédéric Sanchez, with whom she has worked since the 1980s, and Carla Sozzani, founder of 10 Corso Como and career-long supporter, about her enduring vision. Meanwhile, over the summer, photographer Norbert Schoerner captured Jil Sander’s world: her studio, showroom and private residence, her hometown of Hamburg, and the sumptuous garden that so perfectly reflects her unwavering commitment to design, nature and purity.

Jil Sander’s life in fashion began in 1968 when, while working on German magazine Petra, she opened a boutique in her hometown, Hamburg. A year later, aged only 24 and working on her mother’s sewing machine, she launched the Jil Sander label, quickly establishing her signature vision.

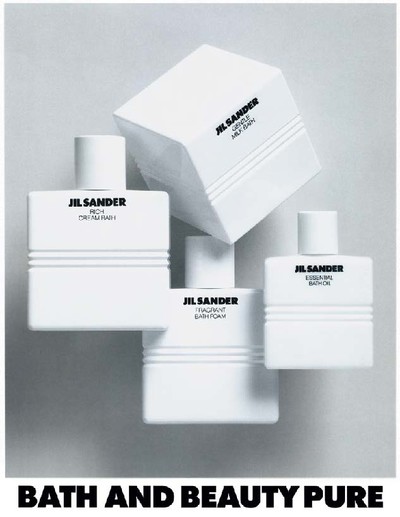

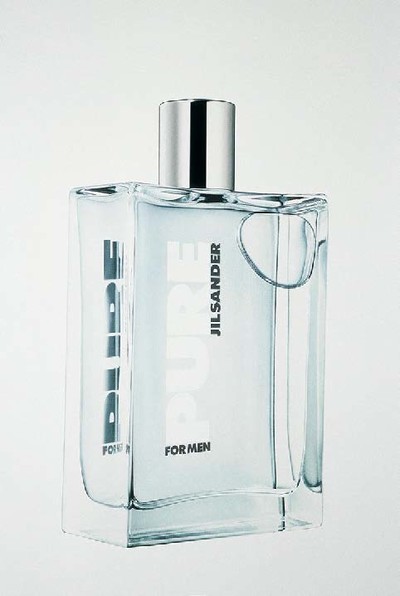

A harshly received first show in Paris in 1975 – journalists proving less prescient about the importance of her radical refinement than her customers – only briefly checked her progress, and by 1979, Jil Sander’s expansion was such that the brand had launched its first perfume, Pure. This was still a relative rarity among fashion houses at the time, as was taking her company public a decade later. With that new injection of capital, the label rapidly expanded around the world and in 1993, Sander returned to Paris in triumph with the opening of her flagship store on Avenue Montaigne.

In 2000, a year after Prada had bought a 75 percent stake in her label, she left. She returned in 2003, only to resign again in 2005 and be replaced by Raf Simons. Her final return was in 2012, but she left for good with the Spring/Summer 2014 collection. Meanwhile, in 2009, Sander began an extremely popular partnership with Uniqlo with her +J line, which brought her increasingly relevant and meaningful aesthetic to a new generation of designers and fashion lovers.

Sander has had a wide-ranging, pioneering impact: her drive to create a complete design world – from fabrics to shows to flagship stores and shop-in-shops – changed the way that the wider industry approached branding and retail, photography and art direction, perfumes and beauty products. Yet through the ups and downs, the hard work and drive, Sander has never wavered from her vision: clothing should be pure, and flattering in its extremely worked simplicity. Indeed, it might be said that Jil Sander’s vision will remain forever contemporary because it has always been timeless.

Jil Sander & Joe McKenna

Hamburg, July 27th, 2017

Jil Sander: I am living in the past right now.

Joe McKenna: Really? I am thinking about the future.

Jil: I usually am, too. But in preparing the retrospective I’ve had to look back for the first time.

Joe: Do you think you are an obsessive person?

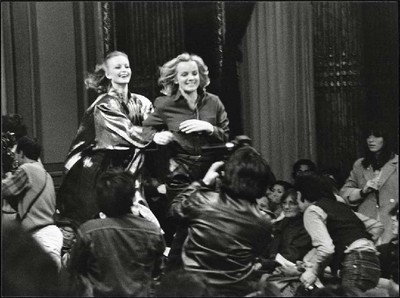

Jil: I am, for sure. That’s something we could both be asking ourselves. We are both quite strong people. We were both ambitious. We wanted to do good work. We learned together how to handle a show, how to go for it. And when we got there, we were happy. Do you remember Masao Nihei, our Japanese lighting specialist? He always asked how I felt: ‘Do you feel emotional? Do you want to be literary, poetic or bright in a “light-up-my-day” kind of way?’ I just saw Frédéric Sanchez who has been with Jil Sander from the beginning. I am so happy that he is taking care of the sound installation for Frankfurt. He remembered so many things. In our first Milan show venue – the Palazzo delle Stelline, a former monastery – he worked day and night on the sound, sitting in a little monk’s cell among hundreds of tapes.

‘The shoes arrived two hours late; the audience was restless. Today, you might just say, ‘Cool, let them go barefoot’. But my nerves were frayed.’

Ingeborg Harms: Joe, how did you and Jil first meet? Were you formally introduced?

Joe: The first time I met Jil was at a dinner Franca Sozzani gave in Florence. I was working in Milan for Prada and drove down that night to attend the dinner. I sat next to you. And when I drove back that night, I thought about our conversation and what a very nice lady you were. It was quite a big deal for me to be sitting next to Jil Sander, because I was such a fan of your work. Then, I think you contacted me the following season.

Jil: What I remember is that I saw you in New York; you were wearing a big sweater.

Joe: One thing I wanted to ask you about relates to teamwork. Tell me about Marc Ascoli and M/M (Paris) and how that collaboration came about? Since that also lasted…

Jil: …a couple of years. You know, doing shows traumatized me. I started in Paris. We showed at the InterContinental Hotel, in the space, where Yves Saint Laurent used to do his couture shows. I did three shows there, but then stopped.

Joe: Why?

Jil: The shoes arrived too late; the audience was restless; we were two hours behind schedule. Today, you might just say, ‘Cool, let them go barefoot’. But my nerves were frayed. So, I packed my suitcase and decided, if they want us, they must come to Hamburg.

But then you decided to show in Milan.

Jil: I became friends with Karla Otto. She was also at the beginning of her PR-work. She always wanted me to do a show, and I’d always say: ‘Yes, but next season.’ I’d have nightmares about it, in which everybody was backstage, smoking; the coffee was cold, and someone suddenly would shout: ‘Right, we have to start!’ It was like being scolded at school. Still, I ended up showing in Milan, and I’d work with Marc Ascoli and M/M (Paris) for the campaign. We placed the clothes on the floor, added a little scarf. Frédéric Sanchez was also with us. And for our campaigns, we did the iconic Nick Knight photos of Christy Turlington and Linda Evangelista. It was the era of the supermodels, a completely different time.

What were your shows like at the beginning of the 1990s?

Jil: They were almost couture shows. Inès de la Fressange walked in my first show in Paris.

Joe: Today, everybody talks about luxury brands, but that wasn’t a word, people used in the 1990s. But Jil Sander was really the ultimate ‘luxury’ brand, because so much time was spent researching fabric, time spent getting the fit right, and time seems to be the ultimate luxury.

Jil: We were together in this.

Joe: No, I think you give me too much credit.

Jil: We had four eyes; we learned together who to cast, how to have them walk. It was fantastic. We were so consistent, we really had a handwriting in our presentations. We were always open to going forward. I always went to the fabric fairs and then directly to the factories to develop new textiles. My fingers were sore because I touched and tested like crazy. I always hoped to find something that could interest me.

You once mentioned that one of your first expressions as a child was ‘selber machen’ – do it myself.

Jil: No, I could never have done it by myself. I was surrounded by people who loved to work with me and supported me everywhere. You can’t do this kind of work on your own.

Joe: In 1989, nobody went to the stock exchange to float a company. Nobody had heard of that. And if they had, they usually had a business partner. But you did it on your own. And then, there are pre-collections, a much talked-about part of today’s fashion business. You were doing them in the mid-1990s. Today, more and more shows are done to make a statement on the runway, creating a visual experience that the world can swipe through on their phones. Your shows weren’t like that: they were great contemporary clothes, and they were backed by the kind of advertising campaigns that photographers dreamed of being a part of.

‘In 1989, nobody went to the stock exchange to float a company. And if they had, they usually had a business partner. But Jil did that on her own.’

Joe, did you always come to Hamburg before the shows?

Joe: Jil invited me to come and look at what she was doing with the view of taking that forward to present something more press worthy.

Was that during the pre-season?

Joe: Yes, Jil invited international buyers in January and July. They came to this building, they spent three days. All the models from Paris or London would come. And Jil did proper shows, 60 to 70 looks with 20 girls. I didn’t know anybody else who did this.

Can you tell us how your label started and moved on to shows?

Jil: Early on in my career, when I worked on photoshoots as a fashion editor, I’d ask the manufacturers to make changes to existing designs; that’s how I became freelance for little collections myself. Then, when I started my own brand, my fabrics were quite particular, and often difficult to realize. I tried to find strong fabrics that were not so womanly, because I was always trying to do 3D-cuts. At the meetings with my franchise people or with clients, there was always a moment when they complained about the delivery times. So I asked my Parisian clients to help me out by coming to Hamburg during the couture-show season, because it would give me more time to produce. I was the first to ask them to do their orders that early, because in those days, they were placed in April and September.

Joe: When will the retrospective exhibition start?

Jil: In early November. We are editing the material at the moment; the presentation will be mostly digital. I just watched our first men’s show again, the one when we came back to Jil Sander the last time. I noticed that, by then, the runway had become longer and longer, so the guests were almost pushed against the wall. And do you remember the tent in Milan where we always worked? Watching the video of the show was extraordinarily emotional because you see all those people who we know again. There are distinct memories for each and every show.

Joe: I really hope that you will have a new portrait of yourself shot for this feature.

Jil: You know how much I hate that.

Joe: Are you photographing your garden for it?

Jil: Yes, and for the exhibition we’re showing a film of the garden with a nice meditative mood. The total exhibition is 3,000 square metres, so the room showing the garden film is a way of relaxing from it. There is an anonymous painting from the early 15th century hanging on the opposite wall, called Little Garden of Paradise. It was done at the beginning of three-dimensional representation. The whole room will be very calm and spiritual.

Joe: Do you garden yourself?

Jil: I try, but there are also professional gardeners who work on it. Everything you see in the film has grown over 30 years. It was quite a process. It’s like a life’s work.

Joe: Are you recreating a garden in the exhibition?

Jil: No, only aerial views on film and in photography. You see the structure, the architectural vision. It is created on a peninsula in a big lake. There is landscaping and a Sissinghurst-inspired area where you have three rose gardens – a pastel one, a white-green-grey one, and a deep-purple one. There is a cutting garden, one for berries, a beautiful vegetable garden, one for fruit trees. For the sake of openness, I left an empty square, which I call Jil Sander Pure.

Joe: Did you design the garden?

Jil: I had a dream after visiting Sissinghurst. At the beginning, we were advised by a friend, Moritz, Landgrave of Hesse, who was a relative of the British royal family. We started with the gardener of Prince Charles. Later, I worked with Penelope Hobhouse. So, it’s what I’d call a ‘studied garden’. I always wanted to meet Russell Page, the famous garden designer. I had a strong affinity to his architectural thinking, but I missed him.

‘In those days, there was a lot of decoration and opulence around – but we had a more modern vision. I was never looking backwards.’

Joe: Why the love of an English garden?

Jil: You know, I am from Hamburg, and we are such Anglophiles. Hamburg has a long tradition as a traders’ city; the men wore great tailored suits when I grew up here. But the affinity lies in the climate, too; we have a joke that we open our umbrellas when it rains in London. The light is important too, it’s always different through the seasons, especially here in the north; with the clouds, the sky is always changing.

Joe: Almost Scottish.

Jil: Yes, and in winter you think things will never grow back, but then the trees explode, especially this year since we’ve had so much rain. As I always say, you can’t beat nature. It’s so beautiful in itself. Of course, you can always correct a little bit. It’s very creative to do a garden, but it needs time and a love of nature – just think, there are maybe 2,000 rose varieties. A structured garden like mine is very work-intensive.

Joe: It’s a full-time job, every season, every day.

Jil mentioned her job as fashion editor before she turned designer, so the photographic dimension of the runway came naturally to her. That’s something, you have in common. Joe, you had been working for magazines, too. You more or less invented the job of the stylist.

Joe: Well, I wouldn’t say that. When I started, there was Ray Petri, but not so many other British stylists. There were American stylists such as Kezia Keeble, Paul Cavaco and Tonne Goodman. They were all there before me.

Jil: You started very early on working with Bruce Weber.

Joe: Yes. I was very lucky to meet Bruce at the very beginning of my career.

Jil: And then our long period with David Sims.

Joe: Do you have all the pictures in the exhibition? Is there a favourite?

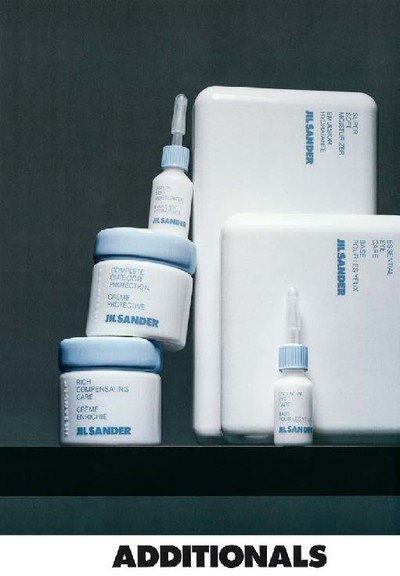

Jil: I don’t know. When I look at the campaigns we did, they fit very well with the shows. We were always very cool the way we presented ourselves. I was never looking backwards. But now, looking back at my runway films, I am amazed how feminine the design was, in a self-assured, slightly androgynous way. A lot of skin and transparency, sensitive, not sexy. Even in my cosmetics I can see this transparency now. In those days, there was a lot of decoration and opulence around. But we had a more modern vision.

Joe: That’s not a word I hear a lot today – ‘modern’. Sometimes it would be good to question that.

For how long had you been in the business by then?

Joe: Ten years. I had worked with Azzedine, that was the first thing. And I guess that’s where I learned that, if you want to do things well, you need time. Today there’s little time to work as deeply as designers would like to. How would you deal with that, Jil? Even in the four years you’ve been gone, the industry has evolved so much.

Jil: I know, I know. I follow things, of course.

Joe: You look at fashion magazines?

Jil: Sure, as a designer you are always interested in everything. I just edited an issue of ZEITMagazin, and went through all the collections.

Joe: May I ask what you think when you are in the role of an editor again, and you look at clothes, touch them and trying them on?

Jil: In that instance, I couldn’t touch them; I familiarized myself with them via the Internet. As always, I selected what I liked. But I found it quite difficult, let’s say from my ‘spoiledness’, to find the right cut, the right proportion. Also, I am from a very luxurious time. In the future, what people show will be tremendously different, what tools they will use, what kind of coherence they will aspire to. Think of those cruise collection shows where people are invited to go to other countries. Or you move an iceberg into the Grand Palais.8 But what I really try to avoid is being solely optical.

Joe: How do you think you would deal in today’s fashion world?

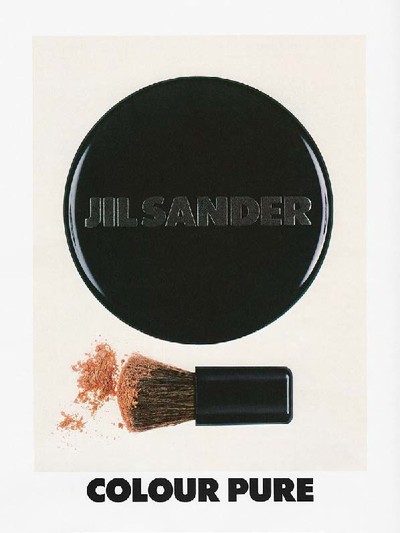

Jil: You have to see that the brand building kept me fully engaged in many aspects from the beginning. That early cosmetics licence…

Joe: Do you know when that was?

Jil: Yes, in 1977.

Joe: Forty years ago!

Jil: Woman Pure was practically the first designer scent that didn’t come out of Paris.

Joe: How do you feel today when you go through an airport and see a Jil Sander fragrance stand?

Jil: I am used to it, because I started so early. I look at how it is presented.

Joe: Even now! Do you miss designing clothes?

Jil: Yes, of course. Like children, we always like to be creative. But I am very careful at the moment. I am also very happy with the experience of going back to the past, the first time in my life. Of course, you can also be creative as a gardener. You can work all day there. But my experience is fashion. I always tried to find innovation or modernity; I always wanted people to feel great, to feel strong in my clothes. You have to ask, what is the value of fashion today? The way people want to present themselves has changed a lot.

‘All my life, people wanted Jil Sander design, but the pricing was an issue. The Uniqlo partnership was a wonderful experience to say: for all.’

The concentration you achieved in your shows stands in opposition to today’s runway culture of big events with many triggers and sensations.

Jil: The concentration saved me a lot – it kept me lighthearted – because you forget everything. Joe, too, is very good at concentrating.

Joe: That’s something I learned from really great photographers and designers. You don’t leave until the job is done.

Jil: You were so intensive. You did not give up.

Joe: I have a photo album that my assistant Claire Mosley did for me. It has lots of moments – two o’clock in the morning, two o’clock in the afternoon – and there’s a page that shows I tried the same look on 14 different models. It was a white shirt with a skirt that looked like an onion skin.

Jil: Yes, we had onion skin.

Joe: The point is, when you make very pure clothes, as Jil did, all the little nuances have to be right.

Jil: As long as it’s not just optical or decorative, that’s the most difficult. As I always say, let’s pretend it’s completely effortless. And yet we know how difficult it is to get there: to this freshness, coolness, nonchalance, and sophistication.

If you have such little decoration, the model becomes very important. It’s almost as if you were casting for a film: character is central.

Jil: We were very open to new personalities. We had a vision that included men and women. For me, it was always very important to see a personality; so when you look into their eyes – it’s difficult to explain – there is somebody, there’s some kind of class.

Joe: But it was easier, because there weren’t so many people in the game. Maida Gregori Boina was one of the few casting directors working.

Beauty was quite coded.

Joe: Yes, there was a moment in the early 1990s. David Sims and Corinne Day were photographing much more real and natural-looking models. At the same time, you also had the power of the supermodels.

Jil: And then there was a change. I remember when another girl type came. The way Kirsten Owen walked, even in 1989, felt like a cool woman, very modern.

Wasn’t that quite an important moment in fashion, too? It was no longer about the créateur, the genius designer who created the way every woman of the moment had to look? Wasn’t it the dawn of street style and of fashion that catered to the individual? The fact that you fitted the same shirt on 14 models says a lot about the versatility of the Jil Sander vision.

Joe: I don’t think we felt that at the time. We looked for certain types of models: classy beauty but with a thought in her head; someone quirky, sometimes. There was a lot less focus on the body than there is today. Perhaps that’s because there is less personality today.

But that was unusual, then?

Joe: At Azzedine or Versace, there was a very different aesthetic to Jil’s. Sexier, supermodels. Some of those models worked for Jil, too, but generally Jil’s models were newer, which made it interesting.

Was it about a more silent kind of beauty, for the clothes as well? You had to look twice.

Jil: In my vision, I can tell you, a shirt and a shirt are not the same. Joe, you always buy Brooks Brothers, and you feel great in that.

Joe: Well, I feel comfortable in it.

How did you go about communicating in those long hours, on the preparation of a show? If I remember correctly, you didn’t really talk so much?

Joe: We did. I would come every January and July to Hamburg for the collections, and then I would stay a couple of days afterwards and chat with Jil and the team. And then I’d come back five weeks later for a few days. There would be samples, things would have evolved. One really important thing, because you talk about looking at people, thinking, what can I give to them to make them feel better? When I mentioned to several friends that I was coming here, they all said, ‘Oh, please ask her to go back to Uniqlo!’ That was such a successful collaboration. Will there be another one?

Jil: At the moment, no. When we left, there was really a big change in my life. Fortunately, I was very busy. In the beginning, I was travelling. And I was also kind of isolated, coming out of that turbulent world of fashion. There had been the stress, running the company…

Joe:Is that because you’ve been a very strong-minded woman who has done all of this on her own?

Has that made it difficult to work with other people?

Jil: I think I’m a team player. I was also the one who took responsibility for everything in the end. When you and I worked together, I was very focused on your side. Although I liked, of course, to be the one who could decide in the end. When I first went to Tokyo, it was quite difficult for me to adapt, since I was obviously not the owner of Uniqlo. But it was also amazing. We said: ‘The clothes are for all people; the future is here.’ We did the shoots over there, too. But it was a big job: we had no studios; we had to teach and motivate the Uniqlo team. We did the sourcing for fabrics. We did the fitting, because the shape is already 60 percent of the quality. I was in Tokyo almost every six weeks. And the result was Jil Sander.

Joe: Very!

Jil: In the last three years, I’ve learned to have a life. To be with friends, but also things like using a cash machine or buying a trolley bag. It’s completely different, completely new. And I hope the angels will tell me what to do.

Joe: I am glad you mention the angels. You would always say that when we were going through a rough moment at work: ‘I hope the angels will look out for us.’

Jil: They do, they do.

‘In the last three years, I’ve learned to have a life. To be with friends, but also things like using a cash machine or buying a trolley bag. It’s all new.’

Joe, you mentioned Jil’s strength and autonomy. Did that create any conflict?

Jil: He’s also strong.

Joe: I probably shared a similar aesthetic, being a fan of Jil’s in terms of clothes and photography. It wasn’t so difficult for me to make a connection. We had some crazy times and experiences together. But at the end of the day, a stylist is there to support the designer. It’s the designer’s vision; it’s not the stylist’s vision.

But there was also the sparring-partner aspect.

Joe: I ask a lot of questions. Maybe, that gives a bit more clarity. I do enjoy a good conversation! Jil, let me ask you something, because it is a bit strange to do a big story on you and not discuss Prada. What did you learn from that experience?

Jil: Since you find me in the middle of this exhibition preparation, I am so deeply inside everything that ‘was’. And there are a lot of memories. So when I think about Prada and that joint venture, it was a time when globalization in fashion started. Accessories became very important. We could also have been an accessories company. We did great handmade shoes and bags, very early. I always said, the wrong bag kills my coat. And I was also an entrepreneur, thinking forward. I thought it could be constructive for the company to grow accessories through a joint venture. When I went public with the company in 1989, we were in a prime situation with many Jil Sander flagship stores all over the world. We were on top of the world, important, we had good ways of working globally, with Asia and the US. We didn’t have debts. And around 2000, it became the fashion thing to do joint ventures, like Mercedes and Chrysler. But do you remember when we were at that McDonald’s?

Joe: We were in a McDonald’s when you told me that you were going to resign from your company.

Jil: It was shocking.

Joe: I understood the decision. You wanted to partner with a group, and Prada seemed like the right choice. They had great expertise and really beautiful, fashionable accessories. It was the beginning of the mania for shoes and bags. It seemed like a good choice, but ultimately the personalities didn’t fit. But it was time for you to step away from it. It was sad, but it was an important chapter in your history.

Jil: You know, sometimes, it’s destiny. As I said, the angels watch. I returned twice to the Jil Sander company, and each time I felt like a divorced woman taking care of her children. I had built my company from the cradle. But then, because of my joint venture with Prada, it became very difficult. Not because I am difficult, but because of the situation. And I became free to do something else: this democratic vision of my line +J at Uniqlo. All my life, many people wanted Jil Sander design, but the price was an issue. It was a wonderful experience to say: for all.

‘Do you remember? We were in a McDonald’s when you told me that you were going to resign from your company.’

Were there moments of great risk-taking that you experienced together?

Joe: No, but I would say that with every show you work on, you are never sure what the perception of that collection will be. And a lot of people worked really hard on each collection, so you want it to be well received.

Joe, how do you, as a stylist, deal with the decisiveness coming at you from the designer’s collection? Do you sometimes eliminate strong pieces?

Joe: No. I like strong pieces! All we can do is edit, edit it down, put it together. And Jil was there every step of the way. It wasn’t as if she was absent for a day.

Jil: The problem was always the time for personal, private relationships.

Would you say the same for your life, Joe, that it’s centred on work, with little time for the private side?

Joe: No, I wouldn’t say that, but like anybody who works in fashion, if you want to be good at what you do, it requires a lot of dedication. I was very lucky, you know, I started as a fashion stylist in London at a time when there were not many other stylists.

I remember you taking a quick nap under the table late at night. And sometimes, when you came back in the morning, you’d change the previous night’s work.

Joe: It happens all the time. The intensity today maybe comes from how fast it all has to be done.

You mentioned that the parameters of fashion have changed, they focus no longer on modernity.

Joe: It’s just something that you no longer hear people talking about. Maybe, because the word ‘modern’ is associated with the 1990s and the early 2000s.

It feels like the notion of individuality is today’s focus. It seems as if we no longer care for the gorgeous 1990s uniform of modernity.

Joe: Fashion has to evolve. As we know, it’s a global industry today, less niche, and that means more consumers, more choices. It’s interesting how important imagery has become to the industry. With the incredible rise of social-media platforms like Instagram, designers realize the immediacy and importance of people talking about an image. But Jil was doing this with her ads for many years. The ad with the shadow on the wall, the ad of Angela Lindvall in make-up… Your ad campaigns still have a very strong visual impact.

Jil: People actually collect that imagery today. They pay a lot of money for Jil Sander catalogues. We are displaying some of them at the exhibition.

Joe: That was another nice part, the catalogues.

Jil: I was very open, never thinking along commercial lines. We always strived for beauty, creativity, innovation. But quality, that was the mission. There was maybe a handful of photographers who delivered that.

As to the shows, they used to be almost half an hour long. How did you maintain the intensity?

Joe: When I worked with Jil they weren’t that long.

Jil: By that time, it was 15, 20 minutes. But before, it was 28! Never ending… And the people were so patient.

How would you create the flow of a runway show? The turning points, the climax, the relaxing parts? Because a show is an artwork, like a play on stage.

Jil: Many things come together. We didn’t have a production company. We chose the best lighting technicians. Light was extremely important. But it was mainly walking, not an event or an environment. When we came back to Jil Sander, we created a diamond or glass constructions for the show space. I always wanted the people at the show to feel something happening, and not only through decoration. I needed authority to be able to show a certain effortlessness, clothes for which you didn’t have to twist yourself.

To get back to the choreography: Jil mentioned that new clothes often arrived on the morning of the show, and you had to exchange the models.

Joe: It was a process.

As to Jil’s vision of cleanness…

Jil: Was there really a cleanness? I’d say it was pure. People sometimes called it minimalistic. But I am no bluestocking – I can do less or more. It depends. Do you think we were so plain? So minimalistic? Even our make-up, our hair, our casting…?

Joe: It was a single vision: Jil’s. I don’t think that it was a case of ‘Was it too clean?’ It was a very consistent vision. And within that vision, you had to move with the times. Jil did more prints; there were clothes with ruffles. It wasn’t always so ‘pure’. And yet, the results still had the authority, so you knew this was Jil’s handwriting.

‘My father got me a car when I was 18, a Volkswagen. But shortly afterwards I told him he could have it back. I wanted to go to California.’

Jil, regarding cleanness in your vision: the fact that you were a child in the rubble of Hamburg, after the destruction of World War II, may place this notion in a different light. Clearing up must have held such a sense of promise.

Jil: I was only born in the countryside because my mother was bombed out of Hamburg when she was heavily pregnant. She stayed with my grandparents who lived in a little village by the North Sea. I was born in that village because there was a military hospital there. I was born at the end of 1943, and when I was maybe two years old, we returned to Hamburg. And I really think when I consider my life and my parents – and I had a second father, since my mother divorced and married again – we had quite a good time. My mother was a lovely person. When it was raining, my brother and I didn’t have to go to school. It was almost the other way around – we insisted that we had to. My brother was in school 10 minutes before eight, always very serious. We were – and still are – very mindful of responsibilities. That maybe comes from the generation that had to rebuild their income, their work. My father built a little company, and my mother took care of her children. She was always light-hearted.

You went to the United States as a young woman.

Jil: I don’t know why I wanted to go away, and so far. Because in those days that was not so common. My father got me a car when I was 18, a Volkswagen. But shortly afterwards I told him he could have it back. I wanted to go to California. So finally, he agreed. I remember when they took me to the airport, I expected him to say at the last minute, maybe, better not. But I went. He was always very careful with his children, who they were with at night. So I kept my pocket money for taxis to be home in time. In California, there was nothing like that, in 1963; it was so free. When I came back to Germany, it had really changed my vision.

What brought you back?

Jil: I came back because my father died very young; he was only 54. Actually, I planned to return to the States after that. My brother was 15 then, and my mother said, ‘You can’t go now’. So I stayed and accepted the responsibility. But in quite an optimistic way. As I always say, you stumble and you get up again. It was a difficult time for everybody. Completely different from today.

Considering Joe’s reference to American stylists, you both received your early visions from the United States.

Joe: Not exclusively American, for me.

Jil: You have an apartment in New York, right?

Joe: Yes, but I can’t say that only America was a big inspiration. I like a lot of American photographers, but I equally like European photographers.

Jil: I also spent time in New York, before I flew back to Germany. Had I returned to the US when I’d wanted to, my life might have turned out completely differently. But who knows, it may have been written in destiny all along. I always had the drive to do things by myself. To dress the way I wanted. But Joe also, I think.

How do you consider the notion of stylishness? Does it have to do with timelessness or with a very keen feeling for the tip of any given moment?

Jil: My vision when I started was directly in opposition to the ‘Madame’ type. I always knew what I liked. When I am visiting somewhere, I automatically start to move things around. So be careful, if you think of inviting me! Even when I worked with photographers at an early age, this tendency was already strong. It took me three weeks to design my first women’s trousers. In those days, they still had the side zip. Today, that can be great, if you know how to do it. But then, I tried to make it… not to be emancipated but to give the cut strength. I was a bit shy, so I thought, I needed power from the way I dressed. You know how it is, when you feel comfortable, like a million dollars?

‘I always knew what I liked. When I am visiting somewhere, I automatically start to move things around. So be careful if you think of inviting me!’

And then, Jil, you developed your own Jil Sander flagship stores.

Jil: We started in 1990, almost 30 years ago, in the Avenue Montaigne, and we opened big flagship stores in the US, in Asia. We had a huge collection; we had to feed 10,000 square-foot stores. Of course, within the limited time constraints of the runway we wanted to express a concept. But when you went to the Avenue Montaigne store, there were beautiful clothes. Every piece had a great level of quality, of workmanship. It was never a selling collection, and we never did clothes solely for the show.

Weren’t those big store spaces also part of your aesthetic? Not for reasons of maximalism or to show the power of the brand, but to allow the clothes to breathe and have space?

Jil: I used to think that we were the ones who created the collections, and that there were others who presented them and brought them to the audience. Then, I understood that you had to work on the overall image as well, to make people understand. If I think about it today, to undertake such a project on the Avenue Montaigne was really courageous. It certainly had a great effect on our success. When I started aged 24, 25, I had to learn everything. I was not only designing, I was everywhere in my company, speaking to people a lot. I spent my life in the Italian factories. Then I built a factory in Ellerau, close to Hamburg.

Joe spoke of pushing things a bit on the runway, and mentioned the quirky model. What other ways are there to give a collection an edge?

Joe: It’s a lot to do with casting. And a great shoe very often helps.

Jil: I just looked at photos from the Cristóbal Balenciaga exhibition in London. How women looked in 1964! The hair, the clothes, Parisian… When I started in 1968, I went to London, you know, King’s Road, punk, expressive personalities: so beautiful. I was stealing from the whole movement; I remember the maxi lengths, for example. I always had this androgynous feeling inside, but never at the expense of killing the feminine part of a woman. And when I started to do men’s collections, I took a long time to develop the drops, to take the shoulder pads out for the sake of a natural shoulder, to develop all the different shapes, the German, the English, the American. I liked to be flexible, because everybody is different. I wanted a collection you can play with personally. And I studied with my eyes. When I see a photo, I see the cut. You can be modern, but stay sophisticated. Fashion is always a reflection of its times. I also always had the grey suit in my mind. But when I look at my shows today, I see more dresses than I ever imagined.

Joe: Would you want to come back to fashion?

Jil: I am very open to finding myself in a new way. I am interested in projects, but I also have a foundation that isn’t specified in its aims yet. So I could use this house for other things besides fashion.

Joe: It’s such a passion for everyone who is involved in the fashion industry. It’s very difficult to step back and move on.

Jil: There is a big change, also in other industries, because of the tools, the Internet, artificial intelligence even.

Wouldn’t you also say that quality is slowly disappearing from the material world?

Joe: As I said, if you want quality, you need time to work on it. And that’s not so available to most of us.

Jil: I believe that there will always be new possibilities. We just have to find them. And there are many positive tools, just think of virtual fitting. Maybe we won’t want fashion shows any more. But we will always need clothes. There are still trends, especially among young people. I think there will always be a group of people with a certain taste level.

Joe: That group is shrinking.

Jil: But there will always be a need for special things. Take the down packaging at +J. We didn’t invent it, but we were very early in making it something that could be stylish. Even in comfort or in casualness, there are certain levels.

But most trends today are not as imperative as they used to be when Paris was the only capital of fashion.

Jil: But wasn’t it always like that? All I am saying: Is there still a dream?

Joe: There is a dream, but it’s more attainable. What I think happened is a need for ‘product’ – owning a product that has a certain buzz attached to it.

And it doesn’t have to be well crafted?

Joe: I think it does, but most things are well crafted today.

Jil: I am not so sure. Give me an artisan who knows his job.

Joe: I’m just saying that everything is very advanced. It’s not so difficult to make a good product today.

We crave products today that are predominantly media-driven. Products happen in the digital world.

Joe: There’s so much fashion content out there and it all needs to be constantly updated. So there’s a lot of ‘buzz’ about things that don’t really deserve it. But there is still a need for creators.

Jil: A lot of brands are trying hard to get it done.

In any case, there was a moment in fashion associated with minimalism. And it came rather late, considering that in architecture and product design, the Bauhaus spirit had been around for 80 years.

Joe: But I want to end by looking forward and knowing what Jil will do next.

Jil: What would you advise?

Joe: I wouldn’t want to say, because you’re a woman who knows exactly what she wants to do.

Carla Sozzani

Paris, August 28th, 2017

Ingeborg Harms: You were an early supporter of Jil Sander. In the show videos that are displayed at her exhibition in Frankfurt, you can always be seen sat in the front row.

Carla Sozzani: Even when she started in Paris, I saw one of those first shows, for sure. Then, when she went to Milan, I decided to follow. In the beginning, I was curious about her decision to show in Milan, given that she’s from Hamburg. But there was so much purity about her work. As much as I am a fashion person, I like it when the shapes are pure. What really counts for me are the cuts, the fabrics, the shapes. I was never interested in gimmicks or too much decoration. Decoration is nice, but I never liked it when you just do it to impress…

…or use it to make the look more valuable.

It does not. When you really see a coat, without distraction, you realize if it’s good or not. Jil’s style was so precise. And it was not minimalism, actually; it was maximalism in the care and execution. You have to remember how much maximalism there is in a minimal dress, because it’s much easier to do it with lots of ribbons. But Jil’s look is sophisticated. I don’t even know why it is called minimalism.

What did it mean from a Milanese perspective that a woman from Hamburg came to show her collections there? Even the fact that you came to see it…

At the time I was a journalist, so I was happy to see beautiful work. The first person in our time who put this look together – pure, clean, perfect cut with no embellishment – was Jil.

What was she like then?

Always very elegant, beautiful, nice.

In Germany, she was considered shy.

Maybe in the sense of being reserved, well educated.

You have curated more than a hundred shows at Corso Como. How would you present a Jil Sander exhibition?

Well, she told me she doesn’t actually have many clothes to exhibit.

Do you like the idea of not exhibiting clothes? Because, aside from not having them, Jil doesn’t want to show former collections physically. She is going to present them digitally.

I think she is right. Everything she did belonged to a vision beyond the clothes. The vision to go public, to do fragrance, the advertising; the vision to be pure. Visuals were always important to her. All of that goes beyond the clothes. Though the clothes were beautiful… the coats! They were the best. And the fabrics, the research that went into them. All this is still inspirational to many brands today. I sometimes see what I’d consider ‘a Jil coat’, yet at the Jil Sander brand itself, they don’t seem to do it. It’s very strange.

‘Jil’s style was not minimalism; it was maximalism in the care and execution. I don’t even know why it is called minimalism.’

Jil mentioned that you were instrumental in her return to her brand when it still belonged to Prada.

It was very easy. I thought the separation was a shame for both parties; it was obviously something that didn’t make any sense. I say that as a friend of both sides. They called me when they were back together as happy people. What happened after that, I don’t know.

You are almost like a homeopathic doctor. You did something similar for Azzedine Alaïa and Prada.

When you are lucky to be friends with people you love and respect, it’s like family, no? You see two cousins fighting and try to resolve it. It’s the same.

Is the fashion world really a family?

It is. We’re all friends, even when we fight. There’s a link that keeps us together.

Fashion and everything that goes with it is a craft. But this expertise remains in the hands of the experts. It is not really taught to new generations.

It is something we should all teach. In Japan, they call it ‘living treasures’.

Bernard Arnault started to cultivate fashion craftsmanship with his Institut des Métiers d’Excellence programme.

It’s great that he is doing this, because LVMH has the financial resources, the power and the possibilities. In the Renaissance, there were schools for high craftsmanship. As a painter, you went to Giotto. Armani is doing a lot in this sense. On the subject of Armani, I love when a brand has the name of the creator, when he is alive. It is a shame that Jil is here – alive, in good health and full of creativity – yet not heading up her brand. If somebody is alive and that’s the case, it’s against nature.

When Jil was watching all her catwalk videos back, in preparation for the exhibition, she was surprised to see how feminine her collections had been. She had often been considered the master of the trouser suit.

Mais non! I never thought of her work as solely androgynous. Even though there are the jackets, the coats, and the white shirt. But Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo were also doing the white shirt at that time.

How do you see the relationship between the Japanese designers and Jil Sander?

There is something about strictness that they share. But the Japanese changed. Rei Kawakubo went in a totally different direction. It’s very difficult when somebody has such an individual voice. It’s impossible to say that you are similar to somebody else. They are never close. They are all individuals.

Individuality is a Renaissance concept. But it is also a German idea. Like Italy, Germany has stayed decentralized for a long time. It was always regional, individual, if you want.

That’s what makes the world interesting. How can you describe something as being American? It’s a huge country! After Martin Margiela, you find all kinds of connections, but before, they were generally all individual voices. How can you compare Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo, Jean Paul Gaultier and Azzedine Alaïa?

‘Designers now put Instagram and the social aspects of fashion first. This desire to make the most of every moment has become an obsession.’

You are making a beautiful argument for fashion designers being artists.

And they all appeared in the same 10-year period!

Did this have anything to do with the political climate?

There wasn’t that much money in fashion at the time. It was not a global concern; there was no Internet. There was no Russia, no Africa, no India in fashion. People used to be in small apartments, because everybody was poor. Creativity takes time. You have to be in a room alone with a piece of paper, a piece of fabric. No magazines, no flea markets. Today, designers travel first class and have salaries of millions. There are press offices and huge marketing departments.

Is individuality disappearing, too?

I hope not! We are looking for it everywhere. I hope I can still recognize it when it happens.

The Internet doesn’t exactly encourage individuality.

The Internet is making a big noise about things that we’ve already seen. Take Barbara Kruger. Today, she is everywhere. But she’s long been an individual voice, a real artist. Now her style is copied all over the world, and it seems that the people who are doing it, are creative people.

Why all this appropriation?

There is a problem. They honestly think they are creative. An artist today is much more social than reclusive. But a real artist doesn’t live a social life. Cézanne’s body of work was not made going to cocktail parties. Nor Picasso’s. But these days, designers put Instagram and the social aspects first. This desire to make the most of every moment has become an obsession. Andy Warhol was going about his business in a very quiet way compared to today’s hype. I used to know Warhol because he was always with us at fashion shows. But the hysteria is going to go away.

Do you think so?

To see Barbara Kruger ripped off like that upsets me, because she is still alive. People don’t think they’re copying; they just think they’re taking an idea. I am of a generation that thinks, ‘I shop therefore I am’… OK? We know. In my store, I sell Barbara Kruger cups and bags…

Do you agree with Joseph Beuys that everybody can be an artist?

Of course. There is an artist in each of us. The problem is to know how to express it.

Isn’t it also a question of support? Yves Saint Laurent had Pierre Bergé.

It’s very difficult to be absolutely alone. But if you build something with someone else, you become two lonely persons together. As for Jil, I think her friend Dicky Mommsen played a very important role. She was like me with Azzedine: ‘Pom, pom, go, you are the best!’ Do you know how much this means in life? Plus, Dickie wore Jil’s clothes beautifully.

Let’s go back to the late 1960s. What was Italy like when you started?

I started working as a fashion editor in 1968 – next year is my professional 50th anniversary. There was couture in Rome, where I used to go as a member of the press. Then, there was prêt-à-porter, which started in Florence. And that was amazing; to me, that was the best system. Everybody was showing 16 outfits, and if you look, 16 outfits are enough because it gives you the essence. And every journalist had six outfits for the whole week. So you could go to lunch, leave your things on the seats. Everything was so civilized.

Was there a genuinely Italian elegance?

It was Italian and French. Everything was happening between Paris and Rome. Couture was in Rome, Valentino was in Rome. Walter Albini was a little bit separate from that. He was what I’d call pure perfection.

Would you draw a line from him to Jil Sander in that respect? Did they have something in common?

Well, obsession is probably their common link. Nothing is good enough or is ever going to be good enough.

You were a protégé of Alexander Liberman.

For a short time. I met him in the 1980s. He came to Milan many times, and when I wanted to leave Vogue magazine for Elle, he convinced me not to leave Condé Nast.

He revolutionized graphic editing. His inspiration were radical Soviet artists like Malevich and Rodchenko.

And what is more beautiful? I remember the Rodchenko exhibition at our gallery; Jil came and really liked it. There are so many things that link art and fashion. Photography, the point of view, and the way people relate to one another.

Today, fashion is more recognized as an artistic discipline.

It is a form of art. It all depends on how you are doing it. Rei Kawakubo is art. Azzedine is art. So is Jil Sander who devoted herself to purity. What I admire about her whole project is that she did everything before everybody else. She went public before anybody else; she did the fragrance license before anybody else. Her advertising campaigns were revolutionary for the time. Yet always with this elegance; subdued, never loud.

You and Jil both started as magazine editors and later moved to a position that allowed for a more direct influence on fashion’s course.

I was fired from Elle after three-and-half issues. I could have gone back to Condé Nast, but at that point I decided that it was that for me. I first opened a publishing company, then the gallery, and then Corso Como.

‘Jil did everything before everybody else. Her advertising campaigns were revolutionary. Yet always with this elegance; subdued, never loud.’

As a concept store, Corso Como brought back the idea of the arts working together, of a new kind of Bohemia.

When I was fired from Elle, I took it as a sign. I was 41 and had already spent 19 years in magazines. I had made a mistake leaving Vogue and I knew it the moment I walked into the Elle office. Because they had agencies who sold them stories. You know, coming from Vogue, where even the glass and the flower bouquets are made specifically for Vogue, the concept of buying in stories was against every principle I grew up with. At Vogue, I had been working with Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Lindbergh, Bruce Weber, Sarah Moon…

Going back to the idea of a new bohemia: Azzedine and Jil may both be obsessive, as you say, but at the same time, they are great team players. Is this capability to orchestrate a team something modern?

But the others are just as obsessive. It’s a group of obsessive people. I am, too. I have this strange thing since I was very young. Before any trip away – no matter how long or short it is – I have to clean my office and leave everything perfect. So whatever happens to me, anybody should be able to come in and find what they’re looking for. I can stay and clean until it’s six o’ clock in the morning until my office is accessible to everyone. Sometimes, I can’t even start working if things are not organized my way.

You left magazines for the 3D world…

I went to three, four, five, six dimensions!

But with the digital world, we are back in the two-dimensional.

I like the digital world, but with Corso Como, the gallery, the restaurant and fashion… I don’t understand how people can stop living. How can you stop having the pleasure of sitting at a table with friends?

Like you, Jil left journalism almost by accident. At first, she just wanted to improve the clothes she had to shoot. But she ended up designing them full-time. It all began when she was hired by the textile producer Höchst to do a Trevira trend collection.

Jil was always very much about textiles.

You, too, chose a hands-on approach to design.

Yes, it’s more interesting this way. It’s what makes life worthwhile. We cannot live it in a passive way. Not everybody can do this, but it’s much nicer to create than follow creators.

Now, we are talking about the new and about living an original life.

Yes, inspiration is one thing. You go to the Cézanne exhibition and might be inspired by seeing those colours – that is good – or you go to Pompeii. But going to the flea market, getting some clothes, sending them to the factory to be copied, and thinking you are creative, well, that’s another matter. It’s quite simply another job.

Jil always emphasizes that her work is all about the three-dimensional.

Of course. Vionnet was very much like her. Actually, Jil’s store on the Avenue Montaigne opened in the former Vionnet couture space.

It’s almost easy to explain why there are so few original voices in fashion today. There is not much space for artistic development when you have to do up to 10 collections a year and satisfy marketing requirements.

There is too much money. Before, the big groups didn’t exist. A designer could wake up in the morning and have nothing to do. But today, the pressure makes things very difficult.

What Jil calls modern and forward-looking seems to be what you call classic. Is that right?

Or radical.

When Jil Sander collaborated with Uniqlo, her slogan was: ‘The future is here.’ Was she being too optimistic?

But her brand still exists! I wish she could still be doing it.

She sees herself as a missionary who wants to reform dressing styles for good. Jil always aimed at dressing everybody beautifully.

Impossible!

Frédéric Sanchez

Paris, August 29th, 2017

Ingeborg Harms: How did you get into fashion?

Frédéric Sanchez: Originally, I wanted to work in ballet.

Did you dance yourself?

No, but I adored ballet and theatre. My approach to music comes from the theatre and the opera, from the idea of a ‘total spectacle’. This notion is important for me. I have been profoundly moved – both visually and aesthetically – by the performing arts, and feel very close to that world. I saw Pina Bausch when I was young, as well as the work of a German director called Hans Peter Cloos,1 who did Brecht’s Threepenny Opera in 1979 in a small theatre around the corner from where we are right now.

The Bouffes du Nord?

Yes. It was marvellous.

Peter Brook did Ubu Roi there, very few props, fabulous energy…

Yes, like that. The Threepenny Opera production was important, because it was done with musicians from the German scene, I think; they were from the group Ash Ra Tempel, using electronic sounds. Before, there had been a play called Susn from Herbert Achternbusch. That really was my youth; these were the things that shaped me a lot.

How did this lead to fashion?

Through music, because we had something called the Théâtre Contemporain de la Danse here in Paris in the 1980s. There were these young companies like Régine Chopinot, Philippe Decouflé…

Chopinot worked with Jean Paul Gaultier.

Exactly. And in London, there was Michael Clarke. Besides contemporary dance, there was the whole Manchester music scene, and Factory Records; with all its beautiful album covers designed by Peter Saville. He later worked with Yohji Yamamoto on his fashion catalogues. That’s how I discovered fashion.

Did you get a formal education in music?

I did French lycée but couldn’t wait for it to end. Music was my passion since I was a little child. Not solely music, more sound in general. This aspect impressed me a lot. Then I got into fashion and met Martine Sitbon and Marc Ascoli by chance. I started to work a bit for Martine. Then a friend introduced me to Martin [Margiela], while he was still at Gaultier, and preparing what would become his own first collection. It came as a surprise to me quite how well Martin and I were a good combination. All of a sudden, we were doing something that resembled a manifesto.

This idea has been a bit forgotten in fashion.

Not just in fashion. But with Martin it was more personal. For me, it enabled me to find my voice.

‘We always spoke about a sound that is very round, a bit like the sound you hear in a truly luxurious car, a sound that is extremely enveloping.’

A personal manifesto.

Yes. Also, with Martin, I turned to a style, which was more arts and crafts. I preferred working with reel-to-reel tape recorders, rather than computers. Anyway, when I started in fashion, it was important for me to do something with my hands, something akin to collage. I discovered cinematographic montage, and I quickly conceived of models walking the runway as images glued to one another, in order to create a story.

And be deconstructed?

Both de- and re-constructed, yes. That became the basis of my work. And that is still there today, even though I’ve since done things that are much more sophisticated. The style of work has remained the same. The starting point is always the image. One or two years after starting with Martin, I met Jil. That was in the beginning of the 1990s.

Typically, were you in close contact with her in the days leading up to her shows?

I set up a studio in the Palazzo delle Stelline in Milan with reel-to-reel machines. Jil was busy in the rooms below, preparing her collection. She would come up and listen to what I had to propose. I really participated in the development of the show and drew inspiration from the fittings. Jil spoke a lot about how the clothes were made, about quality, materials.

How do you translate quality into music?

Through the quality of sound. The purity. I don’t know whether Jil remembers, but we always spoke about a sound that is very round, a bit like the sound you hear in a truly luxurious car, a sound that is extremely enveloping. It was about creating a sound environment of extreme quality which, furthermore, suggests an enormous sensibility. So, it was not about one sound, but of different music, almost moments of life.

Did this music relate to the images you mentioned?

Exactly, and they create a story. What I created for Jil in the first years was quite cinematographic. There was often a beginning and an end. You would hear the music from the beginning again at the end, like the credits in a film. And for Jil I often used leitmotifs.

In the Wagnerian sense?

Yes, ideas which return and transport you back to certain forms. That inspired me a lot. My culture comes very much from German culture, that’s why. Be it Wagner or the music that came after him at the start of the 20th century, like Schönberg and Alban Berg. Primarily Berg. His opera Wozzeck is very important for me. The way he executed it is very cinematographic, with a beginning, middle and end. These are the things I adapted in my work for Jil Sander.

Did your musical work take into consideration other elements of the show like lighting, stage architecture?

There wasn’t really any play with the light. It was mostly white, crude, quite minimal, an ambiance that lasted from beginning to end. As for the architecture, the sound often creates an architecture within the architecture, a specific space, which situates stories.

And then there were the models.

I think that the personalities of the models had quite an impact. But this impact came mostly from the clothes. And, of course, from make-up and hair.

Did all these elements unfold side by side in the conception process?

All this evolved in the discussions we had. With Jil, it was always like that. What I find interesting, too, with Jil Sander, is that you can see periods. In the beginning, there was this mélange of the idea of tradition and extreme modernity. There was a strong sense of the contemporary. In my first season with Jil, David Lynch had just done Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart. We mixed that with European culture. There was this link between Europe and America, more a porosity, a world in between, like that of Susan Sontag who was very influenced by the fact that she had come to Paris and became acquainted with the work of people like Hans-Jürgen Syberberg. On the other hand, certain phenomena of American culture, like Philip Glass or Bob Wilson, were much more known in Europe than at home.

‘There are a few female fashion designers who not only created clothes but the world that went with them. In short, Jil created a house.’

You spoke of periods in Jil Sander’s work.

Then came a period, between 1992 and 1994, which was closer to grunge, even though I don’t like the word. And it was not exactly that. My sound work related to the past, too, to the Velvet Underground, for example.

Again, with Nico, a hybrid of European and American culture.

Then, around 1996, came a period, where we used a lot of German electronic music like Neu! and other new groups like Kreidler and To Rococo Rot, this whole new German scene. To Rococo Rot was a 1990s group, but it related to currents within the German post-war tradition, that went back to Karlheinz Stockhausen or Kraftwerk.

Jil Sander was an exchange student in California in her youth. She says that changed her a lot. And this seems to have to do with American pop culture and the idea of seriality.

There is a certain minimalism of space with Jil, and you find that in American culture, too. But functionality has European roots. The work with sound became very important in a certain moment of Jil’s history. There are a few female fashion designers who did not only create clothes but a world that went with them. In short, she created a house.

So you both really had this affinity for the Gesamtkunstwerk?

Let’s say that I respect the fact that Jil knows where she wants to go. She has the sensibility to know what will work with her. When she came up to my office, she’d always says things like, ‘This needs to be subtler; I don’t feel anything…’

Did you ever reuse what you did for Jil on other catwalks?

No. It was very specific to her. What I did with Martin was completely different from what I did for Jil. In a formal sense, too. Calvin Klein and Helmut Lang, that also was very different. And there is the fact that Jil is a woman. That is very important. I have the impression that a woman creates a world around her. Jil was more in the present, her aesthetic was very much based on reality. While for a man, things are more ‘fantastical’. I think of Yves Saint Laurent who said that he used fashion to realize his fantasies.

Jil’s home in Hamburg was designed by Lorenzo Mongiardino, in an almost Renaissance style.

That doesn’t surprise me. It can be the same thing. The runway music speaks of a moment in time. And yet, when you listen to the 25 years of recordings I made for Jil – either one after the other, or if you switch from 1992 to 2000 – you are always in the same story. There is always this duality of the ancient and the new, the classical and the avant-garde. What binds it together is quality.

Karla Otto pointed out that there are very few catwalk specialists. Basically, there are only one or two for each discipline. And they don’t really train new generations. Would you say that your work is too personal to be passed on?

It is something personal and it comes from far away. The people I work with understand what I do, but they know that they couldn’t reproduce it. My work goes with my life. It’s like writing. My relation to sounds is very particular, because it comes from my family.

How do you know if something works or not?

I see it at once.

And what about the audience? Do you stay for the show itself?

I do, but you press play, that’s it. What interests me is what happens before. Of course, if people come, it’s all ‘awesome, awesome, awesome!’ In the 1990s, people started to either hate or to adore things, that didn’t exist so much before.

Did the collaboration with Jil run always smoothly?

Yes, I considered her comments a challenge. My work was for her, and you need that humility, too. Today it may be more difficult. I don’t know. It was a group of people, Jil, Joe, Maida Boina, Guido Palau, myself… Suddenly, there was a family. It was a bit like a troupe. Like with Fassbinder, who always worked with the same people.

Nevertheless, there must have been more of a distance. Fassbinder actually lived with his people day and night.

And yet, there is not that much of a difference. There is the idea of the troupe. After 25 years, Jil does an exhibition, and she calls me. To me, this is very beautiful.

Is this kind of ‘intensive fashion’ dead today?

When I started to work within fashion, I liked its ephemeral nature. But then the Internet arrived, and archive imagery returned. So, all of a sudden, fashion was no longer ephemeral. Fashion, itself, disappeared; it turned into something different. The same thing happened to music, to art. Today, there is nothing new. Which forces you to become even more personal. I look at nothing any more. I plunge deeply into myself. What inspires me is life itself. Images come, and I want to keep these moments.