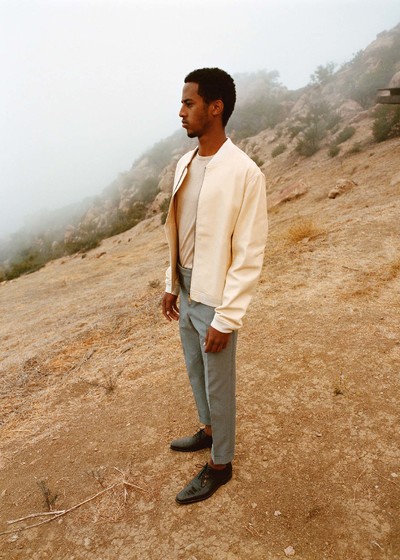

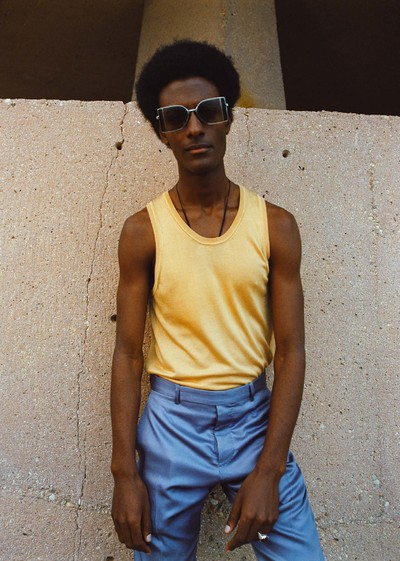

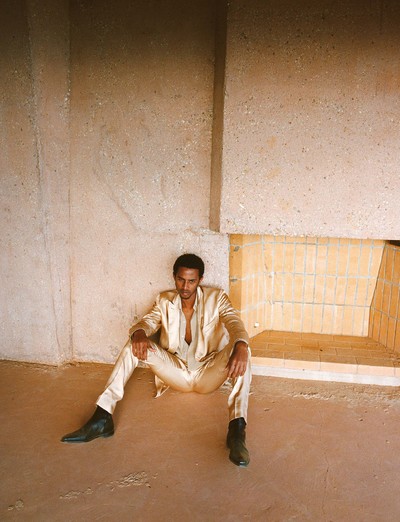

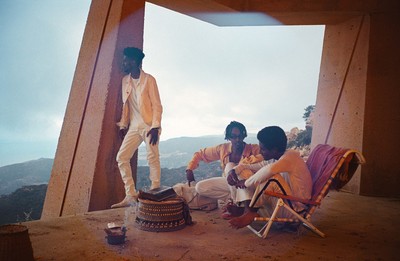

Haider Ackermann and the nonchalant transformation of the house of Berluti.

By Farid Chenoune

Photographs by Dexter Navy

Styling by Haider Ackermann

Haider Ackermann and the nonchalant transformation of the house of Berluti.

Farid Chenoune: I’m going to put my raincoat, bag, phone, and Dictaphone on the table here. I hope you don’t mind the clutter. How do you feel about disorder in general?

Haider Ackermann: I like organized chaos. With me, there’s always something organized in the chaos. It’s controlled, so it doesn’t bother me.

There has to be logic in the disorder?

Do you find that strange?

No, I don’t think it’s strange, it’s always interesting when you’re a designer or an artist. When you say you like organized chaos, is it only you who can find yourself within it or is chaos…

It’s chaos that is only understandable to me, apparently. In my office, however, all the books have to be perfect. That’s my Germanic side, from my childhood, my father. I come from Nordic countries.

You come from lots of countries! Your father was a mapmaker?

He worked in photogrammetry.

And what does that mean?

Cartography, it’s about land maps. Everything is linked, for my father everything was very rigid. Everything was very calculated.

‘There was never a eureka moment – because I didn’t know about fashion. I didn’t know what it was because we were in these faraway countries.’

That opens lots of doors for us… I like the idea of what we owe our fathers; I like the idea that your father was in photogrammetry, and that it was about recognizing territories and I like this idea because the Earth is a surface, with its reliefs, undulating rhythms and a surface of inspiration for artists, materials…

Necessary undulations.

Yes, and it’s interesting to have this very Germanic background, this working on lines, a geometric logic, angles, and his work was to map all those undulations. Did you know all of that when you were young?

No, not really, because my father was always about to leave for somewhere; I wasn’t very aware of that.

So he was always on missions?

He worked long days and then he worked late at home as well.

A traveller and a worker. It’s a question you cannot help but ask when you look at what you’ve been doing since…

It was 2004, everyone gets the date wrong.

Because you are clearly drawn to enveloping and enrobing, draping, and then on the other hand, perhaps this is the masculine side or something else altogether, you are calculating space, clothing space. This idea of geometry is stricter than your previous work, which was more velvety…

Maybe before there was an idea of protection. Why were people from my youth enrobed in metres of fabric? It was to protect them from the wind, from the sun, the violence of the elements, and I think I was very used to that. And I was quite anxious and not very confident, and there was this sort of protection in enveloping women. Perhaps now I am more at ease within my profession; I’ve let things go and now there’s a certain generosity through being stricter.

I’d like to go back to your childhood, and your experience of the clothing that you wore or that the people around you wore…

It was what I saw other people wearing. When you live in Ethiopia, the women are enveloped in metres of fabric, in boubou dresses, kaftans. Then we were in Algeria and Iran, and there it was the chador, women were hidden. We could debate that forever, but it is a form of protection.

Where were you in Algeria?

Oran. Yes, and then also my parents would wrap us up in metres of fabric when we were walking in the streets and in the dunes. So, in fact, fabric and the movement of fabric was always there, always as a sort of protection. But there was always this movement, this draping, this enveloping.

After you learned to sew, when did you first realize you wanted to do fashion?

There wasn’t ever that moment; it wasn’t like a sudden click. It just became obvious; it was just a continuity of what I’d seen, what surrounded me. There was never a eureka moment, because I didn’t know fashion, I didn’t know what fashion was because we were in these faraway countries. I didn’t know who Monsieur Saint Laurent was, who Madame Grès was or Vionnet. All those people…

Your parents had no interest?

Absolutely none at all. We were so far away from all of that, Ethiopia, Chad, Algeria…

Your parents were like nomads?

Oh yes, my father was nomadic and my mother followed him. They were very drawn to all those countries, and fashion was simply nothing to do with us. The only thing that drew me to it as a child was all those metres of fabrics rippling in the wind. And even then, it was the beauty of what I saw – my brother and sister have no memories of that at all.

It’s already not bad going, having one Haider in a family!

Yes, well, fashion wasn’t really something that I knew at all, but I did know fabrics.

How old were you when you arrived in Europe?

I was 12 when we arrived in the Netherlands. Later, when I studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, it was so violent because I was from a world where the aesthetic was so colourful and rich. Antwerp was just the complete opposite of everything I’d known. I admired what Monsieur Lacroix did, and felt close to him and it most resembled my world, but the Belgian aesthetic was violent. Yet it really helped set me up, too.

‘When I was 17, I’d left my parents’ house to go and live in Amsterdam, and was part of a certain sort of life there. I lost myself in the night.’

So that was a vocabulary that you learned slowly…

I learned it slowly, but it made me question myself instantly. It was something in relation to Belgium that was very down to earth…

Not the same earth, but the same relationship?

It was the same relationship and this attraction to extremes, to everything I knew, really touched me. And then I really got into Arte Povera, all the things that were so far from what I knew, but at the same time close to the countries where we had lived in a house made of stone, and so on. When I met the Belgians, and got into Arte Povera, it was all about purity, nobility, the materials.

How old were you when you started studying in Antwerp?

I think I was 19.

Did you do the whole course?

No, they kicked me out. I was there for three years.

It took them three years to kick you out?

Yes.

That’s a long time.

Yes, but they were right. I was always rather untamed. And I was only disciplined when I thought it was the right time to show things. I wasn’t a very disciplined student.

You weren’t in tune with the school’s agenda?

Exactly.

How did you get expelled?

Every year I passed by a miracle because I didn’t always finish the work, but there was enough work that they found beautiful to pass me. There was nothing lazy about it; it was just that I wasn’t ready to show my work. I had my own idea of when it would be ready. I was a bit untamed.

So when you left school, that was when you started working with designers?

No, no, I lost myself in the night. When I was 17, I’d left my parents’ house to go and live in Amsterdam, and was part of a certain sort of life there. I observed a lot and had come from a background that was so far from everything I saw happening in Amsterdam, which I found pretty shocking.

What was shocking?

I lived in a neighbourhood where there were prostitutes, and drugs, so it was pretty hardcore for me. I’d come from the depths of Holland where I’d been very protected and in quite a bourgeois situation. So I was confronted and intrigued by all of that. When I left the academy in Belgium, I wanted to explore the nightlife there and go off in every direction. Maybe I needed that to find myself again.

When you say you lost yourself in the night, do you mean literally, like you became a night owl? Were you drifting?

And also debauched, everything. After the academy in Antwerp, maybe I needed that to understand and to discover, because my childhood had been so far away from all of that. I didn’t see any of that in childhood, so I think perhaps there was a curiosity.

How did you earn a living at that time?

I worked; I had four jobs. I worked in nightclubs, in restaurants, I did everything. I wanted to be autonomous from the age of 17. Being supported by my parents was out of the question; my ego would never have allowed it. I was very responsible even aged 17, very autonomous. I don’t like being told off for anything, so this way if I made a mistake it was my responsibility. I wanted to pay all my own studies. I wanted to go to that academy, when my parents wanted me to stay and go to an academy in our home town. I chose elsewhere, so I assumed my choice and I paid my way.

Are you still in touch with your parents?

Very much so. For them, I was a little boy who dreamed a lot, who was quite absent. So it was hard for them to follow what was going on. I have a very introspective side; I’m very much in my own world. Having travelled to all those other countries where I didn’t always speak the language, you end up isolating yourself a bit – you create your own world. So there is something quite inward-looking about me. I was in my dreams and for my parents it wasn’t always easy to keep up. I knew that was how I was, so it was up to me to assume it.

‘In villages in Ethiopia and Chad, there was always a traditional storyteller. Today, the clothes in my runway shows always come out of a story.’

You were doing lots of little jobs for a couple of years, did you also work in fashion at all then?

I was drawing every day.

You drew clothes.

Yes. I couldn’t see a film, read a book, listen to music without drawing. In sketch books, but it was pretty organized.

So, there was no breaking away or abandoning of fashion, it was always there.

Always. When I was younger I drew all the time. Now it happens more through words. Now things have to be explained; I didn’t need to explain anything before. My drawings and my books could be carried in my dreams.

You draw less now.

Much, much less. It happens sometimes, but much, much less.

When did that change?

Maybe five or six years ago.

When you start a collection, do you still start with drawings?

No. I start with music. Perhaps it’s a sort of egocentricity, but often the collections reflect what I was feeling at the time, they all reflect something that I have felt. Music is the best expression for me to get into that mood. Often lyrics or melodies carry me away and express where I want to go. A reflection of my personal life, which has calmed down a lot. For the collections, I like telling stories, which probably comes from my childhood. In the villages in Ethiopia and Chad, there was always a storyteller, men who would tell stories. So when I think about a runway show, it always comes from telling a story, the clothes all come out of that story. And my mother read a lot. So, we would read in turn to her in the kitchen while she cooked. As we were always abroad, so as not to forget French, she’d wanted us to keep that link. It was very important to her.

And your father spoke to you in German?

No, in French.

Of course, your father is Alsatian, and your mother as well?

No, she comes from Toulon.

You had a wonderful childhood, I think…

Well, it was certainly rich. When you’re a child and you move every two years, change countries and lose your references each time, perhaps it isn’t so easy at the time. But after my teenage years, I realized it was extraordinarily rich. I have amazing memories; I’ve seen things that no one else has seen. I’m very aware now of how wonderful it is.

Especially with a job like your father’s where it was all outside.

It was all outside.

Not in an administration office.

We were always outside. Always outside.

As a child in Africa, were you walking barefoot, which was obviously quite common?

Of course, we ran around a lot with bare feet.

That’s interesting, given that you now work at Berluti. Luckily, they didn’t ask for the CV of your feet!

Luckily, yes. But that said, shoes were always foreign to me; they were something I didn’t really pay much attention to. What’s strange is that things that are foreign, you can actually appropriate quite easily.

Because you have no experience of it, either negative or positive.

You can appropriate the unknown more easily. It’s very beautiful.

Can we talk about Berluti now? You’re working on the third collection. Could you explain to me a little about the project? How do you use this vocabulary to create something? Have you been surprised?

Yes, of course, I come from womenswear. It was completely new, like the other side of a coin. Even if I had done some menswear, it was still very new to me. I was surprised and astonished, but that evokes even more curiosity, there was something incomprehensible for me. And maybe people thought I would take a different path, but the thing that upsets or destabilises me actually draws me towards it.

What did LVMH see in you to offer you this job?

I don’t think I am the right person to answer that.

‘I was surprised, yet incredibly proud to take this job. The Berluti house is a huge challenge and I don’t think I was the obvious choice for it.’

OK. Why you then?

Why me? I have often asked the question, but at the same time I don’t really want to know. I don’t like analysing things too deeply; I get worried I might get lost. There is a sort of freedom in the not knowing – and I am keen to maintain that freedom. If I analyse things too much or understand them too much, I might end up in a certain category where I didn’t want to be. What I can tell you is that I was very surprised and at the same time incredibly proud to take this job, because there’s a big challenge with this house and I don’t think I was the most obvious choice. I think there were other, more legitimate options. But the fact that this house dared to make this choice and that we’re looking at the same path, well, I find that very courageous. And I want to make them proud and prove them right for having made that choice.

You have already done masculine collections, but how are you learning and what is Berluti teaching you?

I am learning everything that was completely unknown to me in the sense of the artisanal. Like the way the house works with shoes. Doing shoes is a very different architecture to being a fashion designer. It’s another profession, one I’m not trained in. I had done shoes, but to have really beautiful shoes, it is a whole other job, another architecture that was completely incomprehensible to me. Now, thanks to the team I have here, I am slowly learning how it functions.

Are you also creative director for the Berluti shoes division?

Yes, and I have an amazing person who works alongside me, who is instructing me. And that is what I love about being here, you feel really alive, in spite of the fatigue, it’s a lot of work. But there is something that’s very renewing, because you’re always in a state of apprenticeship. And I think that is what makes us happiest, the most alive.

Menswear is very much about tailoring, but have you worked much on what we call ‘sleeved articles’?

No, no, that’s the whole point, all this architecture is new to me. And within this architecture, I try and find a sort of comfort. I imagine the Berluti man as another sort of nomad to the nomadic nature of my childhood. It’s true that men today are always in airplanes, taxis, moving all over the place. So I want to have a clear sense of comfort, in the suit as well. In the work I am doing right now, which is interesting, I’m bringing that back to my life, keeping it easy.

What about the draping that you did before?

It’s true that it is more rigid now and that is something new to me. We talk about centimetres and not millimetres with menswear. With me, it’s about finding a certain attitude, it’s not about embellishing men. There is nothing interesting in embellishing a man. What is interesting is the idea of giving him a certain style and attitude. So, it’s more concentrated. It’s good though.

It’s true that menswear moves very little compared to womenswear where traditionally, there’s movement.

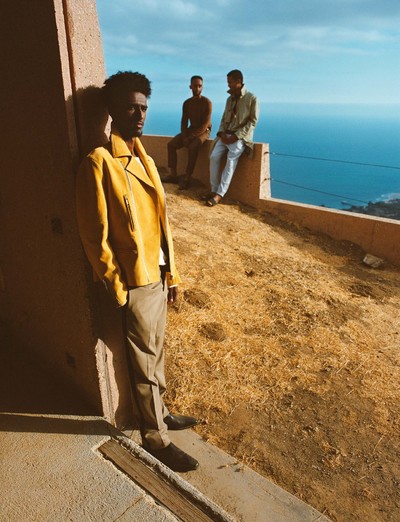

I like to talk to my team about a man, where he comes from. The first collection for Berluti was about a man who I wanted to have a sort of, not complete nonchalance, but for whom a cashmere jacket isn’t his most precious possession. He gets up at 5am and we don’t know where he spent the night. In the morning, he puts on his sweatpants and his cashmere sweater and he leaves. I like the fact he is almost unknown, indescribable and mysterious. There is this mix of materials to give him something other a perfectly ironed suit.

So, no masculine codification. How does it change from one season to the next?

Nothing changes. It is a continuity. There are designers who renew everything season after season. There are certain designers who have that talent and I admire that wholeheartedly. But that’s not me. It’s more like I am writing a book and each season is a new chapter of that same book. My story carries on.

So from collection to collection, it’s a continuing portrait of a contemporary man, the Berluti man.

A contemporary man.

And is this very different to what you did for your own label?

Mine is much more vagabond, more of a daydreamer, while the Berluti man is very anchored in life, he speeds through life. I think my man is what I am and the Berluti man is who I would like to be.

Do you have a personal pantheon of people, real or otherwise, who are like your ghosts? Your muses?

None, that doesn’t interest me at all. I am drawn to so many different things; it could be a man I see at a concert with a velvet jacket, the baker on the corner of the street who wears his apron. It is a mix of all that.

‘The Haider Ackermann man is a vagabond and daydreamer — he is what I am. The Berluti man speeds through life, and is what I would like to be.’

There has never been an embodiment of all that?

No, never. I can be attracted to a gesture as much as by the guy on the street corner. It comes from everywhere, the way someone wears their shoes or bag…

From a fabric point of view, have you introduced new materials? Do you work differently from how it was before?

Berluti was very much about beautiful fabrics; there is a huge amount of taste and sophistication. Perhaps I interpret it differently. I don’t know – I don’t really like to compare myself to what was going on before.

Yesterday I was looking at the tuxedos from your latest Haider Ackermann brand collection, I think, and they had these lighting details, like cracks…

There’s a Leonard Cohen song that I like a lot that says, ‘There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in…’ I always found that very beautiful. Have you ever been to a Leonard Cohen concert?

No, I’ve never been, but I like his work a lot. The way the suit has been almost hit by lightning or by an earthquake, I found that very beautiful.

There was something more tortured about it, but I was in the middle of a breakup at the time.

Is there also that at Berluti?

No, it would be too…

It’s really signature Haider Ackermann.

The Berluti man is much more timeless than mine. There’s no reason why the Berluti man should be about trends and fashion, that would make him uninteresting. The beautiful materials and the savoir-faire we have here, I wouldn’t want that man to stop wearing his blazer after two seasons; it would be silly.

Your Berluti man is not about running after fashion or gimmicks and ending up a fashion victim, chasing an image?

No, that’s not interesting. With Berluti, I want this man to strive for the essential. I want this man to have a wardrobe of basics made from beautiful fabrics. A cashmere gilet. I want them to be simple pieces that can carry over from one season to the next. So everyone can find their niche. I have tried to establish a team here with people who are all very different from each other. One is a punk covered in tattoos, another is a skateboarder, another is very classic. When I first entered this house, Antoine Arnault was surrounded by women and women were designing here, and I wanted the team to be more masculine. I want everyone to find their niche here; I want it to appeal to all sorts of men. And if we succeed with that, then we will have succeeded. It is harder to make beautiful simple clothes, without any ornamentation, to just focus on that simplicity.

Is there a made-to-measure atelier?

Yes, and we have made-to-measure shoes as well.

Could the made-to-measure take inspiration from the collection?

Over time maybe, but for now, I’m concentrating on the creation, what goes straight into the shops, the runway show, the image of the house.

So as you were saying there’s no incarnation, a Berluti gallery…

No, but the house of Berluti has dressed some of the most interesting men in the world, whether it’s Winston Churchill and Jean Cocteau or Monsieur Saint Laurent and the Duke of Windsor. Men who all had a slightly eccentric edge, and I would like to rediscover those men. In luxury, there has to be a bit of madness. I want to find that slight craziness again. In the past with menswear there was an incredible freedom, now everything is so much more codified. It’s all managed and codified. When you look at what Cocteau wore, what David Bowie wore, there was no calculation; it was all an accident. Their style belonged to them. These days there’s no room for accidents.

What you’re referring to is the difference between elegance and codes.

Yes, when you travel in other countries, when you go to Bhutan and see that clash of fabrics they put together, there is nothing calculated about it, all those accidents result in the ultimate elegance. It’s also an absolute freedom.

Getting over this notion of codes that is so ingrained in contemporary fashion — you’re setting yourself a titan’s job!

Not just in fashion, but the world in general. Everything that is politically correct.

Does Berluti have brand codes?

Yes, of course, it has codes. Patent leather is very much part of the house, and the colours, but that wasn’t very foreign to me. The thing that lots of people talked to me about after the first collection was the colours that I brought to the house of Berluti, but it wasn’t true. They were already there, I just brought them out again and played with the codes.

In terms of your own brand, do you think you have codes and signatures that are instantly recognizable?

It’s very hard to analyse my own work. I don’t want to lose the spontaneity, the lightness – no, not lightness because there is nothing light about what we do – but the freedom.

You talked about accidents.

Yes, that’s what is most beautiful. There aren’t any more today. No faults are allowed any more. Before, people had the time for accidents to happen.

[Colleague comes in to end interview]

OK, we can stop there, it’s perfectly imperfect. Thank you.

Photography assistants: Jonathan Folds and Thomas Pat. Film assistant: Diego Andrade. Models: Kalib Tarik at Wilhelmina, Getty, Hanoak, Meron Amahayes, Nate Bekele, Nate Selassie, Sesen Debesai,

Rebecca Amahayes. Hair: Johnnie Sapong at The Wall Group using Leonor Greyl. Hair assistant: Drew Howard. Make-up: John McKay at Frank Reps using CHANEL Travel Diary and CHANEL Le Lift Skin-Recovery Sleep Mask.

Make-up assistant: Heather Polaski. Set design: Victor Capoccia. Fashion assistant: Chanel Gibbons. Tailor: Susie Kourinian. Production: Edward Brachfeld, Margot Fodor, Mark Hobson, Eric Wilcox at Brachfeld.

Catering: Lee Seligman at Kitchen Mouse. Lighting: Vividkid.