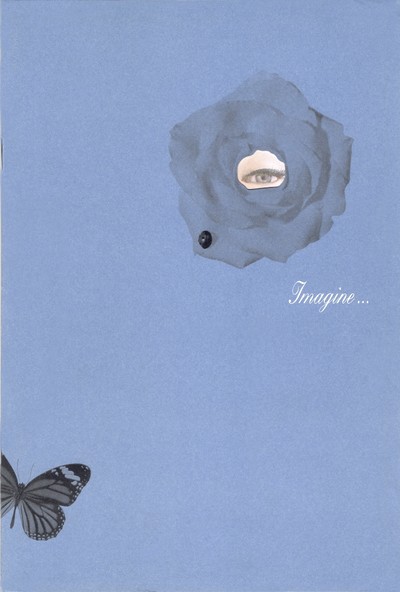

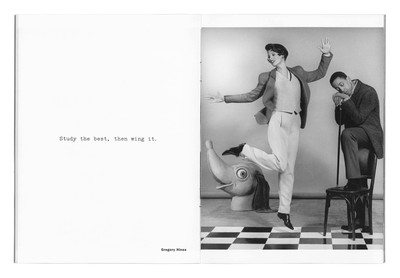

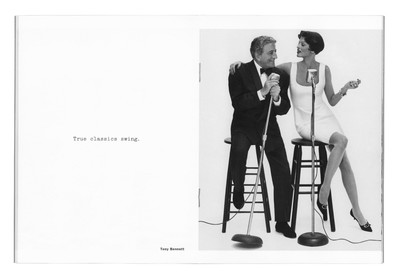

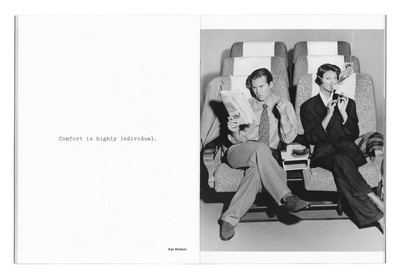

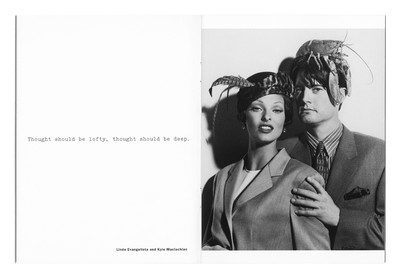

Creative director Ronnie Cooke Newhouse revisits the 1990s Barneys ad campaigns that saw her work with a cast of Steven Meisel, Linda Evangelista, Glenn O’Brien, several lobsters and a chimp.

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

Creative director Ronnie Cooke Newhouse revisits the 1990s Barneys ad campaigns that saw her work with a cast of Steven Meisel, Linda Evangelista, Glenn O’Brien, several lobsters and a chimp.

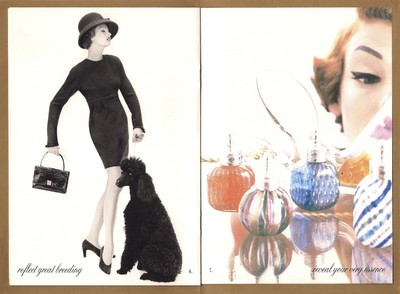

In 1923, a clothing store at 7th Avenue and 17th Street in Manhattan went out of business. The store’s lease, fixtures and stock – 40 men’s suits – were bought by a man named Barney Pressman with $500 raised, legend has it, by pawning his wife’s wedding ring. He renamed his new store Barney’s and began selling discounted, though good-quality men’s clothing for ‘less-affluent customers who had Champagne tastes but beer budgets’, as the New York Times put it. To promote his store, he began a Barney’s tradition of investing in innovative advertising, including matchbooks given out by women wearing barrels and radio ads with the Dick Tracy-esque tag line, ‘Calling all men to Barney’s’.

Barney’s son Fred, who took over the business in the mid-1940s, stuck with the store’s basic principles – quality menswear, altered for free, at reasonable prices – but introduced New York’s men to European chic including Givenchy and Pierre Cardin. Then in 1978, Fred’s son, Gene, persuaded his father to let him open a small women’s department, setting in motion the process of transforming the store into a goto shopping destination. Over the next 15 years, Gene and his brother Bob added new designers (Giorgio Armani was first sold in the US at Barneys), opened new stores – such as the Peter Marino-designed women’s store on 17th Street opened in 1986 – and commissioned photographers such as Herb Ritts and Nick Knight to shoot ads, renewing the brand’s image and reputation along the way.

With the passing of 1980s moneyed glitz and shiny glamour, Gene Pressman decided to take Barneys’ ad campaigns in a new direction, and in 1990 hired Ronnie Cooke Newhouse as creative director to work alongside writer and man-about-town Glenn O’Brien. By then, the company had dropped its apostrophe, expanded into Japan with the help of Isetan, and was deep into planning its ultimate coup: moving its main store uptown to a huge space on Madison Avenue, again designed by Peter Marino.

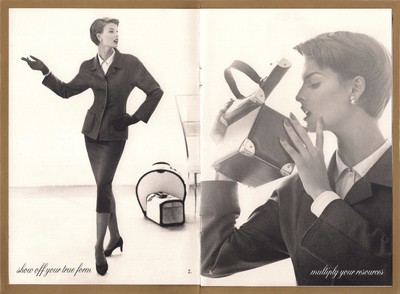

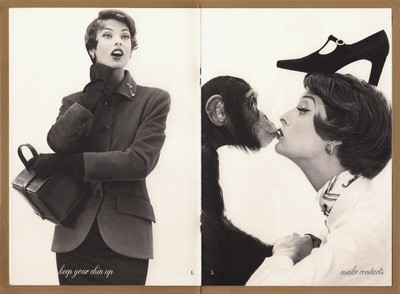

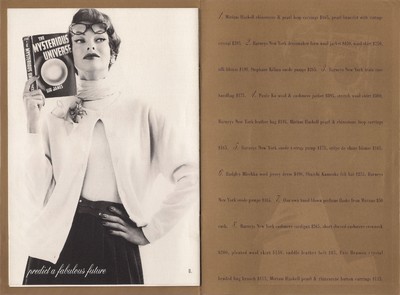

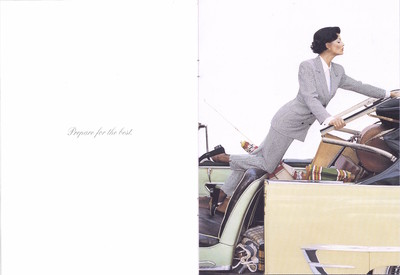

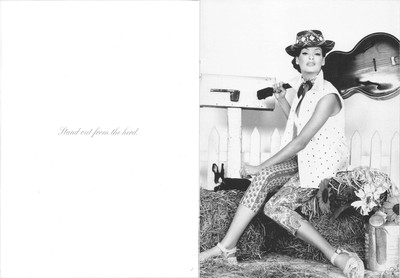

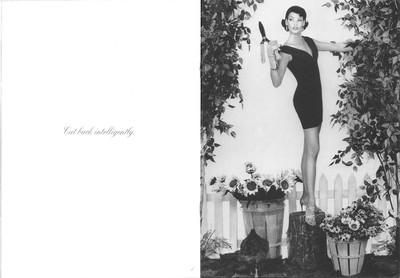

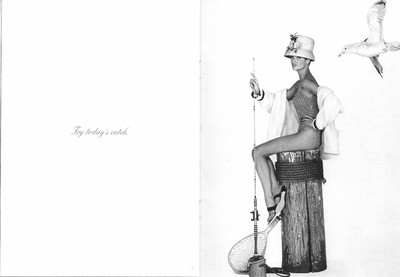

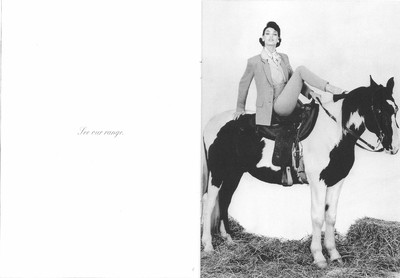

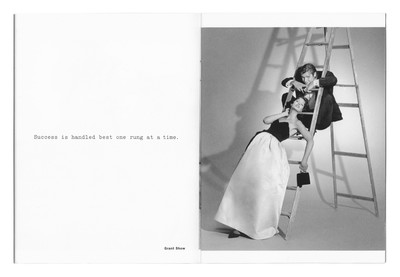

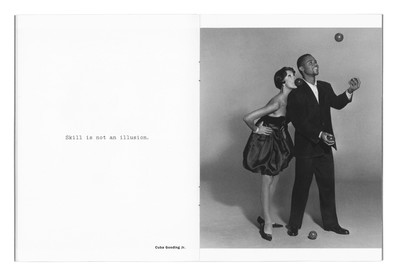

These big steps were matched by the memorable campaigns that Cooke Newhouse delivered between 1990 and 1995: a series of witty, visually challenging and sometimes downright silly campaigns, often shot by Steven Meisel and featuring the era’s best-known faces, particularly Linda Evangelista. The images of supermodels and monkeys, hot actors and lobsters, combined her visual direction and O’Brien’s text to meld downtown sass and uptown sophistication, in the process bringing Barneys’ communications defiantly up to date and buttressing the company’s daringly irreverent image during its rapid expansion. And in the process, Cooke Newhouse and O’Brien proved that fashion advertising didn’t necessarily have to be po-faced and that humour could – and still can – boost sales.

Earlier this year, Ronnie Cooke Newhouse met with System’s Thomas Lenthal to discuss her era-defining work for Barneys, the difference between uptown and downtown, and the precarious future of today’s department stores.

‘Barneys’ owner Gene Pressman would say: ‘It had better be great; it had better be original; I’d better not have seen it before; you better wow me.’’

Thomas Lenthal: Before you became creative director at Barneys, you were at Details, right?

Ronnie Cooke Newhouse: Yes, I was one of the magazine’s founding members. It was a very different landscape back then. We were outsiders, part of the emerging downtown voice of New York in the 1980s. The fashion and advertising worlds were far more advanced in New York than anywhere else at that time. And when I left Details in 1989 – because we were closed down, not by choice – I had to think about what I wanted to do next. I was offered editor jobs but I didn’t think I wanted to work in a magazine; I felt my magazine chapter was over at that point. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I had studied painting. I’d been to graduate school. I had an MFA. So to start with, I was absolutely not doing what I was supposed to be doing. I never figured it out, still haven’t, and I like that!

Sounds familiar!

After Details, I did some writing for Ingrid [Sischy] at Interview, as well as a project that included Martin Margiela. He was very kind and contributed to this fax project, when fax machines were new. I also wrote for various other magazines, and I travelled, and finally went to Mac school. But I just didn’t know where I belonged. Details had been such a place of belonging and it was such a community of like-minded people and that became a very important theme in my life.

You mean working with that group of people?

Working with really interesting elevated people, who were very cutting-edge, whether in music, art, or literature. That was stimulating. Then in 1989, Gene Pressman, who was the son of Barneys’ owner called me and said, ‘How come you haven’t called me about the creative director’s job?’ Fabien Baron, who’d previously been there, had left to go to Calvin Klein, and I guess everyone wanted the Barneys job. And I said, ‘Because I don’t know what I want to do, I’m trying to figure it out’. And he

said, ‘Well, come and talk to me’. And so, I did. And then he was like: ‘OK, Cooke’ – Cookie, whatever he called me – ‘you got two days to figure it out.’ I had always loved Gene and the family, and I liked the idea of working for a family business. Then a friend said to me, ‘You know, it’s not a prisoner-of-war camp, if you don’t like it you can always leave’, which had never occurred to me! So, I thought about it: they had always done some of the most memorable New York advertising; they worked with the greatest minds on Madison Avenue, when those advertising agencies were really significant. I remembered all the great Barneys ads. Then Gene set up an in-house agency and went in a fashion direction, leading the pack. So, it seemed like the right time and the right place to be. Glenn O’Brien

was already there working as a writer.

Full-time?

No, he wasn’t full-time. I sort of knew Glenn peripherally, and we met up and knew lots of the same people. In a funny way, it was like a macho club, but they loved women. And so I went to Barneys and stayed for about six years until I decided to get married, which meant moving to London. And Gene and his family said the only way I could leave was for love, otherwise I wasn’t allowed to leave! It was a very formative time, probably one of the most formative times in my life. Gene Pressman would say: ‘It had better be great; it had better be original; I’d better not have seen it before; you better wow me.’ And in those days, I had to produce like a thousand mailers, print campaigns, outdoor, radio and TV commercials, some of the forgotten media platforms now.

You had a team of how many?

I think there were about 17 people.

So the main players at the Barneys advertising agency were Gene, yourself and Glenn.

Yes, and we had someone who worked on the media, but it was such a small core group, Glenn and I did mostly everything. Gene would come to my office to have meetings; we would discuss everything and show him everything. He wouldn’t come on shoots, but we presented everything. It was all very planned; it wasn’t arbitrary at all…

Tell me about the roles you and Glenn played at Barneys. How did that dynamic function?

I would tell Glenn what I was thinking about visually, my ideas. The dialogue had to start out with something funny. We always laughed hysterically, and we also fought a lot. Like the time he wanted to do a campaign with guys in suits on surfboards. And I was like, ‘Glenn, we are not doing that!’ So, we would fight about starting points, but most of the time I would come to him with something and we would think about the voice it needed together. That was so interesting for me because I had always thought about words alongside visuals, but it’s so hard to do in fashion, and most of the time, it is so horrible. He was unique because he came as an avatar of pop culture, with an understanding of music, art, fashion, poetry and everything in-between. He was downtown New York when it was full of this cast of fantastic characters. We shared that and had references that made sense to each other.

From a European perspective, Glenn was the embodiment of that consummate downtown New Yorker who could give uptown institutions some hip gravitas. That’s how I felt about Glenn.

He could move between uptown and downtown, at a time when there was a big divide. It’s funny because Annie Flanders, who was the founding editor of Details, used to say when she got mad at me: ‘You’re the only one here who could work uptown!’ As if that was a terrible insult.

That is very funny. Could you paint a picture of New York’s fashion advertising landscape at the time?

There wasn’t much. There was Calvin Klein, who in my view really invented the idea of what we now know to be the blueprint for today’s advertising imagemaking – the idea of branding. I think he heralded that in the late 1970s and I think should be given credit for it. It certainly changed so much with him; it was the beginning of something modern. Which is why I went to work with him as his creative director after Barneys.

‘I thought Steven Meisel was the ultimate fashion photographer. He represented what was going on and what was cool, like a barometer of pop culture.’

When was that, the late 1990s?

Yes. There were a few others, but they weren’t as consistent as he was. Calvin used to say to me: ‘The only place I can hire from is Barneys because it’s the only other modern institution.’ There were others. Ralph Lauren was important, because it was very American, but it was a different thing. It was interesting and incredibly well done, but it was a different trajectory and ambition. It was a utopia, but a different one.

You were at Barneys from 1989 to 1996, and the collaboration between Steven Meisel and Linda Evangelista was in 1991 and 1992?

I think it was 1990, 1991 and 1992. We just evolved all the time; we worked with Steven for a while, then we did a campaign with Corinne Day. That was a palette cleanser, and the beginning of the unplugged fashion era.

What did Steven represent to you at the time?

I think I saw Steven as someone who was very downtown and uptown. He was the ultimate fashion photographer who I often saw out with amazing people including Warhol. He represented what was going on, like a barometer of pop culture and what was cool.

He was a hip name?

Yes, he was in a way, but he was also very Vogue. Even when he did 1950s glamour, it just kind of made sense. Steven was pure fashion, but he also gave context to what was going on around him. I think he’s the greatest living fashion photographer.

Did you think that back then?

Yes. In a fashion context, he was like no one else. I mean there were other photographers who were doing other amazing things, but he was a hero.

I seem to remember that this was a moment when Steven was working almost exclusively with Linda. He would do an entire year of Vogue Italia covers with her. Why was that?

Because Linda was an extension of Steven’s vision, and they were amazing friends. We didn’t have a stylist on the shoots. I brought along the clothes, edited them down into a range of what we had to cover for the buyers, and then Linda and Steven would just kind of do the rest themselves. It might have been my stupidity of not really understanding, but there weren’t really that many freelance stylists at the time. They worked at magazines. And I just thought Stephen and Linda could do a better job together. Because it seemed like Steven could do everything.

The results were good though! Typically, how many shoot days would it take to do one of those mailers and ad campaigns?

Maybe two days… He shot the campaign and I always designed a mailer besides the print campaign, with the images to send to the customers.

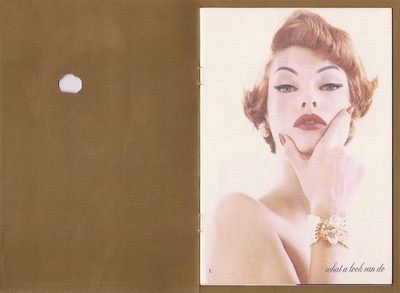

Did you arrive with specific references or concepts?

Yes. I knew exactly what the sets should look like. I started at Barneys in the middle of a recession, which wasn’t great, so I wanted to make the advertising a bit like the original Flair magazine, but with a combination of beauty and humour. It was sort of an amalgamation of the movies I had watched, mixed with memories: 1970s indie-style movies, Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant glamour. There were also very camp influences; I was probably more influenced by the Lower East Side drag shows.

So you would bring in pictures of those movies?

No, I think I put together drawings and layouts. I would look at the images and Glenn would sit on the desk facing me and write the text on Post-its. He would write, and I would say, ‘That is terrible, that is amazing’, and we would laugh. My basic thinking was, ‘Well, if the economy sucks, we may as well entertain ourselves’. Barneys’ ground floor was an inspiration – it was like something from the golden era. It was very glamorous in the way that movies were in another era. I’d go to Europe with my family a few times a year on holidays growing up, and the ground floor always had that feeling of French and Italian speciality shops built in the 1930s, but a Wes Anderson-like take on them.

An American sophistication.

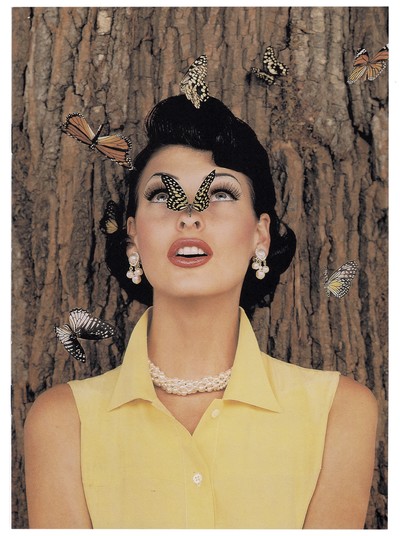

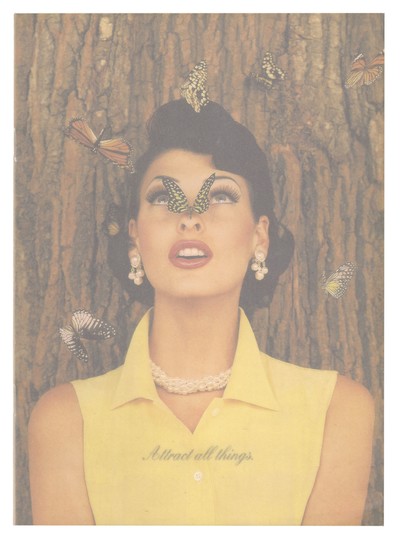

Yes. For me, Linda’s red hair was very Lucille Ball, which made me think of the comedy with the monkey, Monkey Business. So we decided to get a monkey in.

And the image with Linda and the butterfly, that was completely prepared I would imagine?

Yes, there was a TV show called Green Acres, in which Eva Gabor goes to the country, and it was quite like that. The thing about Linda was that she had a great sense of timing and comedy; with another model you couldn’t have done that. She was more than a model; she could have been a glamorous comedian. And that’s very appealing, this supermodel with a large character. And it was all just ridiculous! The thing is that New Yorkers like humour, there is a tradition of humour, and Barneys advertising always had that tradition, too, which was also smart. It was still always about selling, so introducing humour into fashion was a scary thing to do. Steven has the best sense of humour and Linda was his muse, but he was also terrifying to me back then. He could be scary because of his mind and talent; they were intimidating those two. But also so fun. Almost no one did sets back then, and Steven was like: ‘Where are we going to find a set designer? We’ll need to get a Hollywood film person in.’ Simon Doonan, who was the greatest window designer, employed a freelancer named Bill Doig, who in his spare time sold antique furniture, and was a very quirky guy. I had Bill work with me on these sets, and we did a lot of it together. Then literally, throughout shoots, I would stage different surprises. For example, I had a truck arrive with a whole load of chickens inside and when Bill opened the door of the truck, out flew the chickens and Linda reacted for the camera. I kept this going all day long, like TV-show entertainment. Because I had read somewhere that directors kept their actors entertained in order to get reactions. I was kind of learning on the job!

‘Barneys’ ground floor was an inspiration – it was like something from the golden era. It was glamorous in the way that old movies are.’

Tell me about the dynamic between Linda Evangelista and Steven Meisel. They were the best of friends, right? They seemed to be constantly shooting together?

They were always together; he was very close to Linda, Naomi [Campbell] and Christy [Turlington]. Linda was very willing to experiment and change her hair colour for each shoot and become a character. I think he must have found he could reinvent her all the time, quite Pygmalion-like.

Back then, Steven Meisel seemed to be very interested in American aesthetics between the 1930s and the 1960s. It was almost all about Hollywood, it felt very musical and very upbeat. Was that also a conscious thing for Barneys back then?

I don’t think we thought that deeply about it! It was really a question of what amused us. I think it just made sense. Also, we were attracted to periods that were really stylized, that had aspects that were timeless and influential – and I think Steven was, too.

How did people respond internally at Barneys?

They absolutely loved it. Mr. Pressman, Gene’s father, was a huge supporter of the work I was doing. And it wasn’t just the campaigns, it was all the mailers and other stuff that I worked on with a lot of designers who were part of Barneys. A lot of houses didn’t have their own identity back then. Now you couldn’t do any of the things I was able to do then because today every house is so defined by its own identity. They don’t come to you now and say, Oh sure, do what you want. So even with notable designers we were trusted to do what we wanted, in a sense. We would think about the brand, but we always had to think about Barneys and that was why it was so different from any other department store and looked so modern. We didn’t take a house and create a mailer that looked like that house. It always looked like Barneys; we’d take that house someplace else. It was very creative and new, and everyone knew those were the codes and they accepted it and wanted to be part of it. But it could never happen again. We had a small-space ad on page two of the New York Times, a few times a week, for which we always photographed still lifes. There would be the credit information, but also Glenn would write anecdotes about what was going on politically that week. I would be watching David Letterman and he would be holding up that day’s New York Times with the ad, laughing about something written in it that was completely taking the piss out of whatever was going on. So, we were political, and yet it was also all about showing original products, with humour and culture.

What are your thoughts about Barneys and the slow demise of the American department store? It seems that they are a dying breed.

I think it’s sad that department stores are struggling, but maybe they haven’t kept up. And when all the designers opened up their own brand shops around the world that are these spectacular places and offer a more complete collection, it is hard to compete with that. And I don’t think department stores have figured out what their role should be – and there is a role. I think there is a way to save them, but I think they have to be a hell of a lot more daring. They have to be more daring in their buying and more daring in how they show things. They’ve gone very corporate; it’s not very interesting.

‘The thing about Linda was that she had a great sense of timing and comedy. She was more than a model; she could have been a glamorous comedian.’

But what happened to Barneys?

It’s under different ownership, and I think you can’t beat the passion of the Pressmans; it was infectious. I mean it was with them that Peter Marino’s career blossomed. They launched a lot of careers.

Did the uptown building, which was designed by Peter Marino, already exist in 1990?

No, just the downtown building. He had done part of the downtown space already, when he was still wearing a bowtie and khakis. Barneys didn’t exist uptown at that point, nor in LA. Nor did many of the others. Peter Marino did the uptown building while I was there; we opened it in 1993. Actually, this is a good moment to clear something up. This is really key: for the opening of the uptown Barneys, I had seen something on my media-buyer’s desk — advertising space on taxi tops. I mean, they were only ever used at the time by the likes of Virginia Slims…

…or strip clubs.

Or accountants. All very low profile. And I said for the opening of the uptown shop: ‘Let’s buy every taxi top in New York, it would be amazing.’ So we did a campaign with Jean-Philippe Delhomme’s artwork. One side said, ‘Going Uptown’ and the other side said, ‘Going Downtown’. And that was the first time anyone in fashion had ever used taxi tops. Some journalists have claimed that Helmut Lang was the first, but we were way before, and we continued to use the taxi tops. We kind of owned it, then we stopped, and Helmut continued it.

I understand that for Gene Pressman, money was never an object. Is that true?

That’s why they don’t own it anymore!

It certainly felt like that. It just felt so generous, the whole Barneys proposition. It was very joyful to look at and really inspiring. Compared to what was going on in Paris in the 1980s and 1990s, it felt intelligent and beautiful and precise and well-made.

Paris had the clothes, but we had the image.

It was considered vulgar in Paris for fashion brands to advertise. I remember Saint Laurent advertising through their cloth manufacturers; it was drapers who paid for it.

Sometimes when I am in the Vogue library, I’ll look at French Vogue and American Vogue from the same time period and it is interesting to see the big differences. French advertising remained very ‘local’ at the time.

The Americans were way ahead, the French were still back in the 1950s in terms of how they envisaged communicating about fashion. It was like, We don’t need to, we’re the best.

It’s amazing how everything’s changed.

I sometimes wonder if it’s about the freedom or the clients. I bet Mr. Pressman must have been a pretty demanding customer, but he was supportive and understood what you were doing. How different are clients today to Gene Pressman?

Budgets were smaller compared to today. There were fewer people on shoots; there weren’t countless assistants. There are so many more deliverables now for so many different platforms and formats. Around the same time, I worked on some cosmetic projects and that was like going back in time 40 years. Barneys was a kind of unique little oasis. If the designers have freedom, then I do too. That simple!

You have already mentioned Simon Doonan. Was he already at Barneys when you were there?

He was always at Barneys: he worked on the windows and all the visual merchandising, and when I left he kind of moved a bit into my place. Simon was great; the head buyers were as well. It was a really special group of people. Even the difficult ones were great. It was really passionate, and being difficult because you’re passionate is very tolerable.

And everyone knew for sure they were the best at what they were doing, and that Barneys was the best place to be doing it?

It felt like I was at a great graduate school, and I was getting my PhD.I was totally hooked. I felt like I had found my metier. Now that’s a good conclusion!

‘It’s sad that department stores are struggling today, but maybe they haven’t kept up. I think they have to be more daring in how they show things.’