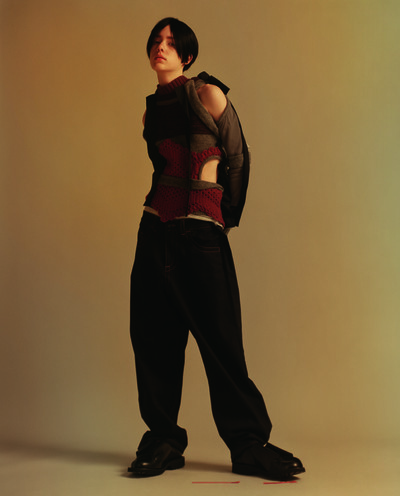

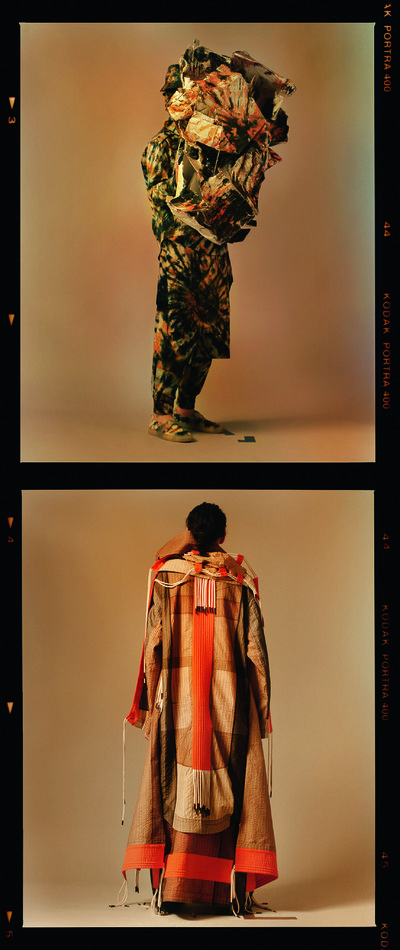

Mixing function and folklore, ritual and gender, Craig Green is redefining menswear.

By Hans Ulrich Obrist

Photographs by Lena C. Emery

Styling by Camille Bidault-Waddington

Mixing function and folklore, ritual and gender, Craig Green is redefining menswear.

Craig Green’s story reads like a route map for young British designers to follow. First, complete the MA in fashion design at Central Saint Martins. Then, using the momentum of your graduate show land a spot with Lulu Kennedy’s support platform Fashion East or the British Fashion Council’s NEWGEN. After three seasons, having solidified your position as an emerging designer in the press and winning the trust of buyers, go solo. If you’d like, then you could always apply for the LVMH Prize or the ANDAM, and in the process gain more recognition and advice from industry professionals.

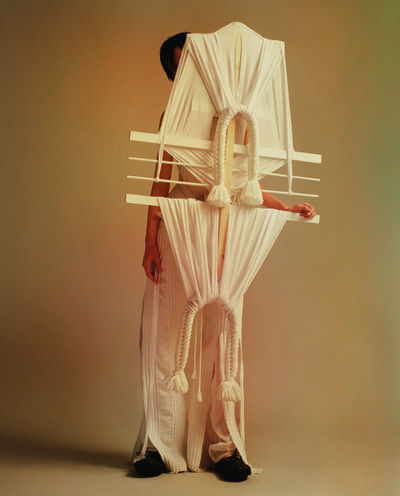

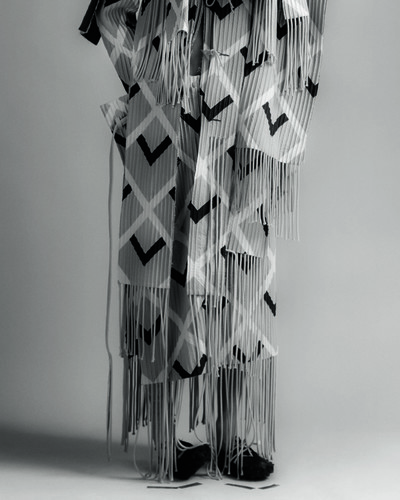

None of this will happen, however, without the sort of raw design talent and clear vision that Craig Green has shown since his first collection in January 2013. The London-born design er started small, first working out of his parents’ house in 2012, then at the Sarabande Foundation – set up in memory of Alexander McQueen – where he had a studio until late 2017, always helped by close collaborators, who are often also friends and family. While his business has grown, his vision – built on the foundation of his MA graduate collection, created under the nurturing eye of the late Louise Wilson – has remained constant. His ongoing investigation into ideas of function and protection, ritual and folklore, has produced menswear that is complicated in its simplicity and speaks across gender and geography: beautifully cut “uniforms” with carefully judged detail. He has also made each of his catwalk shows a celebration of artistic freedom. Originally at Central Saint Martins to study art, he has created sculptures for almost all his collections, transforming basic and found materials (plywood, tennis balls) into portable, wearable structures that complement and play off the clothes. While this has occasionally created some background noise – the face masks in his first collection, made from broken garden fencing, provoked a wave of sneering vitriol from Britain’s most conservative tabloid newspaper – his approach has been hailed by both buyers and critics who have praised its deep emotional resonance. Indeed, Green’s vision collects new converts with each passing season.

Artistic director of London’s Serpentine Gallery, Hans Ulrich Obrist, sat down with Green to discuss how the designer discovered the work of artist Rachel Whiteread, how he studied in Walter Van Beirendonck’s library, and how he creates clothing inspired by nuns and knights.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Let’s talk beginnings. Was it an epiphany during your childhood or adolescence that led you to fashion or was it a gradual awakening?

Craig Green: I come from a home that was really unrelated to art and fashion. My dad is a plumber and my mum is a nurse, so no one from my family is in a creative field at all. But our house was always filled with building materials, like big immersion boilers, and so was our garden, which was always really overgrown. I always had these things surrounding me, as well as people who made things. My mum was a Brownies leader, so she was always doing arts and crafts, and I guess we came from a household of just making things. I’ve always liked to draw and originally I thought I wanted to be a portrait painter, because at school it was one of the things I seemed to be good at. But at that point I didn’t even know what Central Saint Martins was; I’d never read a fashion magazine. I was going to study art because I wanted to be a painter or sculptor.

Did you grow up here in London?

Yes, north-west London, just on the outskirts, Hendon. It’s a bit like a village-y community.

So, the countryside?

Almost. It’s on the edge of London where it has loads of green fields. People don’t really think of it as London; it is on the motorway that leads you up to the north. It’s one of those places where everyone knew each other in the pub, everyone knew each other’s business. I went to the same school that my mum and my grandfather went to. It is like a village within London. In terms of an ‘epiphany’, it was more of a gradual process. I applied to Saint Martins because a friend of mine’s dad was a prop maker for the BBC, and he said it was the best art school to go to, so I went to the open day with them. Then, when I was on the foundation course, there was something about the people I met on the fashion course: everyone was there all the time, and everyone would go out together and work really hard. I was really drawn to that community feeling. I applied to the fashion-print course, because I thought that if I am bad at making clothes, then at least I can maybe paint or draw. It was very haphazard actually. I feel like you can’t really make mistakes any more in how you choose your education because the fees are so high. When I was there, I was lucky enough to have a scholarship.

‘My dad is a plumber and my mum is a nurse; no one from my family is in a creative field. But our house was always filled with building materials.’

It’s very different when your education is free. You can experiment more.

Yes. I thought I could maybe go on the fashion course for one year, then change at the end of that year and go back on to the art course. I was lucky to have that freedom to pick and choose as it went,

which I imagine is very different to now

You were testing things. The future is often made of fragments from the past, so did you have any role models? Who were or became your heroes and heroines?

I was drawn to Rachel Whiteread. I loved the pure and simple but really ingenious idea of what her work was about. Fischli & Weiss was one of the first things I saw at the Tate around 2007; they had that full room where they’d remade things in other materials. But from the very beginning, it was the painters Lucien Freud and Jenny Saville who I found inspirational. I was obsessed with realism and trying to paint something exactly as it was. I didn’t really know anything about art. I just liked to paint and draw at the beginning, but then when I discovered other artists, I guess my mind was a bit more open to that.

It’s interesting about Rachel Whiteread and Fischli & Weiss. From the beginning, it seems you had very sculptural inspirations.

What I loved about Rachel was the idea of space, and that it was also a physical form like a house. Maybe there’s something about that: our house was always full of people; the door was always open; my mum would make friends with everyone; she was very social. She was also a childminder, so after school there would be like 10 children every night. We had animals and it was all about our house. So maybe there was something in that.

So you had artists who inspired you, but you also had a mentor at Central Saint Martins, the late Louise Wilson. This interview could be an opportunity to pay tribute to her great influence. She was someone who helped so many people. How did you meet her, and what was you experience with her like? I never really spent time with her, so she has always been this mystery to me, this amazing person who was at the beginning of everybody’s career. What was the secret of Louise Wilson?

Just to backtrack, I had two very important teachers. The first was my A-level teacher at college and the second was Louise Wilson. When I finished my bachelor’s degree, I didn’t know what I was going to do – whether I wanted a job or if I was going to do a master’s. Then I met Louise and she offered me a place with a scholarship on the Saint Martins MA fashion course. What I loved about her was that you always knew exactly where you stood; she would tell you if you looked fat or if she didn’t like what you were wearing. There was no beating about the bush with Louise. And what was amazing about her was that she very fearlessly encouraged you to do what you wanted to, not to worry about things, but just to enjoy the moment and what you were doing at college. On the bachelor’s course, it never really clicked for me. I was never making work that I really liked, and I wasn’t at the top of the class. But I had a much better time on the master’s course with Louise, and I felt like we understood each other. When you respect someone like that you strive to make them proud. It is a motivation because you want to do well by her. Also, she was one of those people who would come in the morning and say: ‘I woke up last night and I was thinking about those trousers you’re making, and I really think you should do this.’ The fact that she cared so much it almost took over her life, that was inspiring to me and probably everyone there.

So, her life was all about these other people she cared about.

Yes, I think so, and it showed in the work and the people who came from that course. She had amazing opinions on fashion and understood it on so many different levels. To be able to understand the work of 10 such different students, and to encourage them down their different paths, is a huge skill. But what made her so inspiring was having someone who cared that much and who made you care about what you were doing.

‘What I loved about Louise Wilson was that you always knew where you stood; she’d tell you if you looked fat or if she didn’t like what you were wearing.’

There’s something magical when someone inspires so many people. How did she help you?

She made you realize that nothing is ever finished and nothing is ever complete. Even up to the last minute everything is open to change. Just because something took you ages doesn’t mean it’s great, and because you did something quickly doesn’t make it no good. You can rip it up and start all over again. She would make you question your work as well, and that was important. She was strong and strict and, above all, honest, which I think that is very rare in a lot of industries now. So many other voices can tell you things, but they might have an ulterior motive. Louise had a pure voice; you trusted her and you wanted her to trust you. When we were on the course, between students we were all telling stories about Louise. We would go to the pub and someone would say: ‘Oh I heard from another student that she did this to them or this.’ It all worked to make everyone really care and be there all the time. It was teaching us: ‘If you don’t care, then why should I?’

And who was your second influence?

He was called Andy Barby and he was why I ended up going into further education in art. He was a teacher at Hendon School and passed away a year after I left, just after I had started at Saint Martins. I remember he taught me one really important thing, which I guess is something you don’t realize when you are younger: that it’s usually 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. Just because you have the ability doesn’t mean it’s going to happen. He instilled in me that hard work is the most important thing.

Do you have fashion heroes or heroines?

My one hero is Walter Van Beirendonck, because I was lucky enough to intern for him when I was on my placement year. He is quite community-ish as well, which is something that comes up a lot with me. It was a very small studio, with only one other intern, and when Walter was at the Antwerp Academy he would let us use the studio, as well as at weekends and the evenings. He had the most incredible library and I spent so long educating myself while I was there. I remember when I discovered his work about halfway through my fashion course. At the time in British fashion, it was all very floral, and that idea of dark feminine sexuality, but I never really fitted in with what everyone else was doing. I remember finding his work and that was when I shifted into menswear because he made me realize that fashion could be about anything and come from anywhere. I love Walter because he never compromises – and that is an incredible and rare thing in fashion.

The idea that fashion could be anything is interesting.

It didn’t need to have a tradition or what my rather naive idea of fashion was at the time. It didn’t have to be that. It could be about anything; it could be about you, even if you don’t have the most interesting background or childhood, or you weren’t drawing dresses from a young age. That was when I started working with wood and sculpture, because my upbringing was all about building stuff. Besides my dad being a plumber, my uncle was a carpenter, and my other uncle was an upholsterer; it was all very physical. My after-school job was dismantling sofa and pulling the staples out of things.

At weekends, I would help them do up houses and things like that.

You’ve mentioned that Walter Van Beirendonck never compromises – that leads us nicely to your first collection. A lack of compromise is like you and your approach to fashion. Is that first collection the beginning of your visual resume or is there earlier work that you still consider valid?

There are some house sculptures that I made for my MA collection that I still think are good. I guess that’s where it kind of started. The first collection was based around the relationship between workwear and religious wear: one was for a physical function and the other for a spiritual function. It was about the similarities in the utilitarian functions of them both, and the idea of one size fits all. It was my first catwalk collection and the clothes were kind of sexless and almost genderless in some way.

Tell me more about the first collection. It was not only very sculptural, but you erased the face. Where did that come from? It became a cause célèbre in a similar way to certain art shows in the 1990s. How did you deal with the ensuing criticism and the instant fame?

The show was in January 2013. It was a very strange, double-edged time. We had just got a studio and everyone working on the collection was either a friend or family; we did it with almost no money. The fabric was calico, which we washed and painted. The wooden sculptures were just fence panels from B&Q. The whole idea came from an image I found of an old collection I’d done and I’d scribbled over this person, scratched them out completely. I’d drawn on a photograph, and I just thought, ‘Oh wouldn’t it be amazing if we could make it look like the person had been scribbled out?’ So we literally just smashed up the wooden fences and put them in piles and then joined them together. We then made a replica version of that instant and chaotic energy by painstakingly snapping wood to

make it the same as the original version. So, it was almost the idea of replicating something that was not replicable. Then in terms of covering the face or shielding people, our brand is built around the

idea of workwear and communal ways of dressing, and there was that idea of protection that runs through everything. That show was really about everyone who helped. It was very much a group effort. I really can’t believe we got that collection together, you know. To begin with, I was doing it in my bedroom at my mum’s house, and we got a studio halfway through. Then when we showed it and the reactions! When you are young and doing your first collection… I remember thinking: ‘Maybe this isn’t for me. It’s a joke; my work is a joke. Maybe I should do something else.’ There was definite doubt.

‘My first collection was based around the rapport between workwear and religious wear: one for a physical function, the other for a spiritual function.’

How do you pick yourself up after that? How do you get to the next collection?

All the media things were going on over the first collection and people were making it into a joke or being offended by it, and I was kind of shocked that it would get that reaction, especially because so many other things that have happened in fashion are more shocking than that. I just thought the sculptures were beautiful objects to see walking, more than anything else. Maybe it was because it was the first ever men’s London Fashion Week, and there was so much more media there, so it got picked up in a different way. But people later helped me see the opinions that really mattered, fashion people who had liked it. Looking back, it was a good thing to split opinion and to make people react, even if they hated it. That’s still better than no reaction at all.

Like Walter Van Beirendonck, you did not compromise. So, the next collection…

…was all about chaos and control. It all started with a tie-dye technique that is can never really control the outcome. Everything was hand-dyed. There was this idea of making someone look as

if they had been crushed or squashed into a ball. We made the pieces in 3D and then painted the tie-dye onto it, so it looked like a 2D visual from the front, but like a 3D smashed visual from the side. We didn’t give in, we just made something more extreme again. This one was more painterly.

That was 2014?

The end of 2013. After that, we didn’t do sculpture in the collections. We made these hand-painted rugs on a table with four bags of paint. We were painting them and folding and opening, over and over again. That was kind of obsessive, like things being overly ornate and that romantic idea.

The Spring/Summer 2015 show coincided with the aftermath of Louise Wilson’s death. It was a very emotionally charged moment for you and many people in the fashion world. It was like a shockwave.

It was a very difficult time for everyone.

You seemed to capture that moment; there’s a sense of mourning in that collection. How did you channel that? Was the collection an homage to your tutor?

I think it probably was an homage. With that show we went from the really painterly, really overworked collection to making everything out of cotton and bare feet. It was all about a minimalism, which I guess is something Louise always stood for. It was a very weird emotional time. I think she passed away a month and a half before, so we were about halfway preparing the collection. I remember the morning of the show, when we got to the venue and John Vial, who does the hair for the shows and was a very close and very old friend of Louise’s, mentioned something about her. It was just a weird and emotional day; everyone was upset and started reminiscing. But yes, maybe indirectly, it was an homage to her. That was our first solo show; the three before that had been group shows with Fashion East. The sculptures in it were very instant; they were just pieces of muslin and we knocked them up like two days before the show. We were walking up and down the street with pieces of muslin and I just loved the way it moved. We were trying to think of the most simplistic way of joining or adjusting a garment, and that is where all the strings and ties came from. We kind of cinched garments in. They could be tied together in different ways.

‘I remember thinking: ‘Maybe this isn’t for me. It’s a joke; my work is a joke. Maybe I should do something else.’ There was definite doubt.

It was very architectural and minimalist.

The clothes had an environment around them, in some way. When we were making them, we liked the idea of it being a protest, but a protest about nothing, a silent protest. That was the main idea. Our press releases sometimes sound as if we start from the beginning with these concepts, but it is really about reacting in the studio: ‘Oh, that feels nice’; ‘I like this piece of fabric’; ‘What about this?’ And usually there will be 10 failed attempts at things that don’t even relate in the end. We just allow it to happen. I guess that comes from Louise Wilson as well. Just because it was the first idea, and you spent ages on it, doesn’t make it the right idea.

There is often something of the procession in your collections, an idea of medieval rituals that appeal to all the senses. In some of your collections, there is something almost monastic, with armour and protective shields. I was wondering if there is a connection to the Middle Ages?

I think there is, even in my MA collection. I’ve always loved clothing that has a purpose and I love religious wear; there is something so beautiful and simplistic about it. So that balance between the two is always like a constant conversation. Sometimes it goes deep into protection and armour, and then even if it starts as workwear, it often ends up feeling spiritual, maybe.

Wearable wooden sculptures and the idea of obscuring the face were back in the most recent collection, but this time with fabrics attached…

That collection, now I look back at it, felt like it was all about time. We were joking around with the idea of past, future, and present, which maybe sounds like an X-Men movie.

There was a red and yellow sculpture and a monochrome brown one, which had a very strange sculpture in the middle.

I loved that they looked like doors – or a portal to somewhere – but also that they looked like confession booths. And I like that the fabric in the middle makes it look like if the model layed down he would be like a human seat, but also like a prayer cushion. And there are ropes like they use to swing the incense that swung when they walked. I loved the idea that they looked like scales or

some weird balancing thing. I also like the way they look like an ugly clock, a cuckoo clock when they have those hanging pendulums underneath. If you think about it in terms of past, present, future, they would be the past.

And then the future and the present?

The present was a sculpture that looked like you’d photographed a jet-ski from above and then there was the seat and the protective parts of the jet ski. I like that they flapped, like a flying machine or a bird, when the models walked. It looked like they were trying to fly or like a kite. There was an idea of movement and the futuristic idea that they can fly. There was also a sense of naivety, the idea that sometimes knowing too much is negative. The clothes were about that idea of seeing, like maybe seeing a photograph of something and not knowing what it was made of and then trying to recreate it, but in all the wrong materials. It was as if every time we thought of something futuristic it ended up medieval. So at the end of the collection, for example, we had these futuristic shapes that were put onto things, but in fact the shapes were taken from Celtic flags joined together. It was that idea of when you’re trying to be futuristic, you end up coming full circle and being medieval.

So there is a medieval connection…

Yes. With the last collection, the line-up of 30 looks was almost the most traditional thing we could think of, but it was also the most futuristic thing we could think of. It kind of came full circle.

So, the past present and future come together.

Yes, like with the idea of movement, of futurism.

And when you say we, who is we?

My team: seven full-time and two part-time.

So when someone is not wearing one of these structures, it becomes a sculpture. I was wondering about this double sense because you started out doing art, then moved into fashion. It’s as if you are still doing sculpture.

Yes, I guess so, but what I think is fun about fashion is that there’s always a person involved and they have to walk. It’s really like problem solving for the body: what it’s like being next to it, and how that changes.

‘Every time we thought of something futuristic it ended up medieval. We made futuristic shapes that were in fact taken from Celtic flags joined together.’

Obscuring the face was in your first collection and it keeps coming back, like an eternal return in the Nietzschean sense. Where does that come from? Is it connected to giving your models a sense of anonymity or gender neutrality? From early on you’ve always emphasized the unisex character of

your collections.

The core of everything is always based around the idea of communal ways of dress or a group of people who wear the same uniform. Which I guess relates to cults or a work force or a school uniform. I remember when I was a kid and we used to think that a school uniform was really oppressive and we really wanted to express ourselves, but then whenever it came to the no-school-uniform day – when we could wear our own clothing – all the richer kids would show off all their amazing clothing and their fancy trainers, and the poorer kids wouldn’t be able to. It was like people were being compared to each other for what they had and judged, when usually, on the days we wore uniform, everyone was equal. That idea of a work force or a group of people goes back to the idea of community. I have an obsession with that and the idea of protection and the idea of how it’s not about the individual, but about the group as a whole. That might also be related to obscuring the face in some way.

Did you conceive of the collections as gender neutral from the beginning or did this gradually develop over time?

Whenever we have done things like robes – you might call them skirts for men – there is always that idea that this was, and still is in certain communities, deemed to be men’s dress; it’s not about a man in a modern women’s dress. There is always an idea of masculinity running through everything. It is also about functionality.

There is a lot of debate in the architecture world at the moment about communal living; there is a bigger emphasis on communal space. You talk a lot about communal dressing and that seems to put your work in sync with that movement. It’s something democratic because it crosses genders and

people…

I’ve always felt that there is something very romantic about that vision of a group of people all wearing the same kind of dress, because you don’t see it very often. People don’t even wear suits and ties to the office anymore; you don’t see groups of nurses walking down the street. It is something that has been lost. Sub-cultures are different to before; now everything is much more globalized and mixed. It isn’t a negative thing; it’s just a different era. But I just love that idea of community and a communal way of dressing. I think that goes back to where I grew up, and my crazy

mum’s house filled with people.

Does your mum come to the shows?

Oh yes, she always comes. She was wearing one of the paradise jackets last time; she loved it. My parents have been very supportive since the beginning.

A uniform can feel very ritualistic. Can we talk some more about rituals?

That maybe takes us to Spring/Summer 2016, one collection of sculptures that we’ve skipped. I’ve always been obsessed with the symbol of a circle. I love horror films, and they draw that protective circle around themselves to stop the bad things coming in. Then there are circles of people. I always look up the meanings of circles. It’s the sun and the moon, and I like that it’s an equal distance from the centre all the way around. The sculptures in that show were called ‘walking operating tables’ by someone, because they look like the sheet they put over someone during an operation. There was also the idea of emphasizing the most vulnerable part of the body – like in cartoons, when people die and their souls leave their bodies and fly away. That’s what those were about.

That idea of the ritual has always been there. At the very beginning of my MA course in 2011, I won a competition to do a shoe collaboration with Bally of Switzerland and the whole collection was based around the original Wicker Man film. I’ve always loved that film and I always look at folkloric ideas of tradition.

Did they produce the shoes?

Yes, once. We hacked up shoes and then put them back together, with cork and leather. Like worker boots mixed up with sandals; those kinds of ideas. We wanted to use natural crepe and rubber.

Have you designed shoes since then?

We did a collaboration this season with Grenson. We wanted to make a shoe that would look like a toy soldier’s shoe, so we had all the ridges down the back and the front, like it had been made in plastic. That goes back to the Rachel Whiteread idea of taking something out of a mould.

‘I’ve always felt that there is something romantic about a group of people all wearing the same kind of dress, because you don’t see it much any more.’

The first fashion designer I met as a student in the 1980s was Helmut Lang, he told me at the time that he didn’t want to open his own shops but infiltrate the existing system. What are the practical

and business realities of being a fashion designer? Can you tell me about the economics, the idea of your brand and how you have remained independent?

I remember when we had to write our first business plan. Up until then it was about solving each problem as it came up, and enjoying that things were still happening. Then we had to write what

the brand was about and where we wanted it to go, but fashion is so haphazard and things happen and change so quickly that it is very hard to have a plan. You can have a loose plan, for the next six months or so, but it is forever changing. I think maybe that is why people within fashion are so obsessed with change. Fashion is never allowed to rest; it is a never-stop kind of thing. What I love is that I’ve managed to keep the brand independent, and that allows me to make decisions I feel are right. A lot of the people who work at the brand have been here since the very beginning or have stayed a long time, and it is like an extended family. We spend more time together than we do with our friends and actual family; we work really long hours, every weekend, travelling together. The idea of having someone come in and tell me who can stay and who can’t terrifies me. I want to decide which decisions I should make; the idea of having to justify my decisions to someone else scares me.

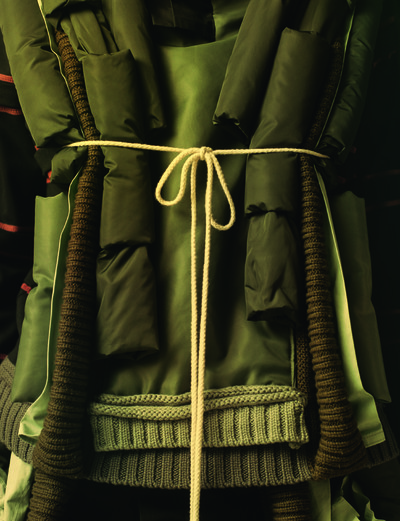

It’s your business, but you do work on collaborations. How did the one with Moncler come about? How do these collaborations with bigger commercial brands operate?

When we were first approached by Moncler, I couldn’t initially see the similarities between us. I wasn’t sure about what we would do. Then I began looking into their history, and it’s all about functionality and protection – which is something that we also investigate, but in a different way. When I think of Moncler I always think of that specific shape and about things being solid but as light as air. That’s Moncler. We have done two seasons of capsule collections with them now. In the first, we played with ideas of form and ideas of protection and functionality again, and we looked at down fetishists who dress in multiple layers of feather down and sleeping bags. The collection’s shapes ended up looking very Bauhaus in terms of structure; they had solid ‘roundedness’ about them. Moncler thought it was like a spaceman, someone else called it a poodle man, and then someone had a more sexual reference: they called it anal-bead man. I like that idea that one person can look at something and see something innocent, and someone else sees something sexual or dark, even though it’s the same thing.

We recently did a presentation of the project and Skepta came along and wore the pieces. What is exciting about working with Moncler is that they have the ability and the factories to do anything. As a young brand, you are working within the constraints of the factories or the suppliers you have around you. Also, Moncler is very open to what I think might be good. They are very open to strange ideas, which is rare.

And then there is the cinema. I am particularly fascinated by your costumes for Alien: Covenant and that Ridley Scott noticed your work. How do you go from the catwalk to big screen?

Janty Yates, the costume designer who has worked with Ridley Scott on a lot of his films, tried calling the studio and couldn’t get through. So she turned up in her car, knocked on the door and told us: ‘I am Janty Yates, here is my card. I’m working on the new Alien film and saw some of your pieces. I sent pictures to Ridley Scott, and he is into maybe borrowing some samples to see them in real life, and then maybe we can go from there.’ And her dog was barking in the car and she had to run out, and it was all very chaotic. And then I realised that it was Janty Yates who is the Oscar-winning costume designer for Gladiator. Later I found out that she had gone to Selfridges to have a look around and had seen our Autumn/Winter 2015 collection. She said that it related to exactly what she had spoken to Ridley about and his ideas for the new Alien film, which was kind of a mix between medieval and futuristic. It was the collection where we had the jumper with the hole. Weirdly, when we were doing that collection, we joked about how it looks like the scene when the alien jumps out of the chest in Alien, and then a few months later, we met Janty Yates. So I don’t know if there was a weird universe thing going on there. It’s funny because I remember watching all the Alien films at my best friend’s house when we were in primary school, but never did I think that I would even get to meet someone in that world, let alone be a part of the Alien legacy. It was such a surreal and exciting thing to do

‘I like the idea that one person can look at something and see innocence within it, while another person sees that same thing as sexual or dark.’

We haven’t talked about that Autumn/Winter 2015 collection, in which faces aren’t obscured, but there are repeated holes.

For that collection, we did T-shirts that looked like scars, and sewing them onto the body to adjust them. We had red looks in the middle of the show and black and white dotted throughout, so if you saw the collection lined up, it looked like a striped flag. Janty had seen it and wanted the twisted jersey bodysuit for all the sleepwear in the film.

That was your first cinema experience?

Yes, and it was amazing how many pieces we had to make for the film. Each actor needed 12 of every single one. They were all hand-sewn, so it was a nightmare because you have to put them onto a person to sew them. I think we made like 150 full suits in jersey that had the twists all the way.

We’ve discussed all the collections…

There is one collection left! The one before last, the multicoloured one based around the idea of paradise, with stretched stripes. The clothes were made out of sportswear jersey, and we also had the paradise ponchos. We began by looking at paradise in an innocent way, until a friend of mine said: ‘Oh, but paradise is an aesthetic. It is not a thing – it is a negative idea.’ I had never thought about paradise like that before, and we ended up with this idea of darkness and playing with different ideas of paradise.

A dark paradise! It’s like an oxymoron.

Yes, a sinister dark paradise. The sculptures for that collection came about from trying to make a weird exercise machine. That idea of going to the gym and the aspiration of making your own ideal body relates to paradise. Some of the sculptures also look a bit like a parrot, a bird of paradise or an animal being dissected. Like a dissected frog when you pull the skin back. And someone said the ropes on them looked like a girl’s pigtails as well, which was sinister. The lines started off as pretend talismans. I like the idea of a talisman that is believed to have power, because that’s again the idea of striving for paradise. And then there were the ponchos at the end with big patchwork scenes of parrots. I liked the idea that wearing it, you could stand behind someone, and become the backdrop, like when you take a photo in paradise. Also, I liked that the sculptures looked like they were measuring the body. People often say the most symmetrical face is the most beautiful, so I liked the idea of breaking it up, and dissecting the body and measuring to test if it’s perfect.

Now we’ve discussed all your collections, even if we’ve slightly jumped around, how would you describe the overall story of your label?

I always think that each collection is very different, but other people always say they’re the same, but twisted. Someone said each one is the story of what it is to be a man. Maybe that is just because even if we try to be very different every time, and find something else, we always come back to one idea.

Like a leitmotif…

Sometimes it is spirituality, sometimes it is about protection, more militaristic, and falling in line. There’s always that exploration of the different ways it is to be a man, maybe. Talking about the collections like this makes our process sound really conceptual, but we never start with a concept. We are about reacting and then, as we are building the idea, things are all over the place, but then it all weirdly comes together in the end. I like the fact everything is open to interpretation as we build the collection; we’re not strict or directive. That’s why our show notes are always just a piece of paper with two paragraphs that don’t really describe anything, but just set the scene. Because I think it’s really interesting to see what other people see in a collection.

Do you ever collaborate with visual artists?

I collaborate on the sculptures with a friend of mine, David Curtis-Ring; we’ve been friends for a long time. We build sets in the studio together. In terms of visual artists, it’s mainly photographers like Dan Tobin Smith; he shot the last campaign. He is an amazingly technical photographer and is great to work with because nothing is ever impossible. We are working on a campaign that we are shooting next week, where we are burning these huge versions of the Spring/Summer 2018 sculpture. We are making these huge burning effigies outside, all with coloured flames, but we just found out it’s going to be minus 10 that day.

‘People say symmetrical faces are the most beautiful, so I liked the idea of breaking it up, dissecting the body and measuring to test if it’s perfect.’

How do you typically start a collection? Do you sketch and draw?

I am always drawing things.

You have notebooks?

No, just weird bits of paper that I then fold up and put inside my bag.

And always by hand?

Yes, I do computer drawings because you have to for the factories, but I always think there is something nicer about a handmade drawing. That’s where those smashed fences came from.

What about any unrealized projects? Architects publish books about their unrealized projects, but there are rarely books about artists and fashion designers’. Do you have dreams or unrealized projects within or outside fashion?

I’ve always wanted to do something in architecture. I’ve always loved ceramics, too; they are so tactile and functional. I love the materials, and the fact that they last forever. I’ve always wanted to make furniture, too. I think I just love making things. Some of my favourite days are spent just making something in the studio, even if that’s really rare now. Fashion is sometimes so overwhelming.

There should be a monographic book of everything that you have done.

We often laugh and say we should do a book of all the terrible things we’ve made that no one’s seen. A book of our failed attempts. We have photos of all of them. Because one day we are like, ‘Wow, this is amazing’; then the next, ‘This is terrible!’ It would be a fun book.

In just a few years, you have created an amazing body of work. You must now have a younger generation of fashion designers looking up to you for advice. What would you say to a Central Saint

Martins student now reading this?

I think that inspiring someone is probably the whole reason I went into fashion in the first place. I remember being at Saint Martins and one of my main aims was to be in a book in the library, and for a student to open it and make it part of their research. I think that is such an important thing to do. And for a long time, I wanted to be a teacher. In terms of advice, though: work very, very, very hard and never ask someone to do something that you wouldn’t do yourself or are not prepared to do. That is what I have learned and what I have done. You have to dedicate your whole life to it, but if you love it, it doesn’t matter, because life is work. It’s about devotion.

Which designers of your own generation do you feel a kinship with? A proximity, maybe even a friendship?

One would be Nasir Mazhar; he is an incredible maker, a hat maker and, I think, a sculptor. He’s based in London and he’s a real creator. He stands by what he wants to do and never compromises. He is completely self-taught and if you ever go to his studio, you’ll see that he just makes things through the night and all day. There are lots of half-finished, weird and incredible hat inventions. He is a real genius, I think. Then, Raf Simons is a huge inspiration to everybody. He has a story within his work, which I think is very important, especially with menswear. He paved the way for everyone in menswear. I really like what Simone Rocha does, too.

I had lunch with her recently. She’s extraordinary.

She is doing Moncler, too. She is doing the women’s and I’m doing the men’s. I feel that she creates such incredible work, which has a really clear story as well; it’s just amazing. The other people I like in London are all people I feel strongly about, and from what I understand they are all very nice people. That’s important to me: working in a way that is respectful and about being kind. Kindness is key for everything – I think it comes across in the work of people who are good.

I think the keys to the 21st century are kindness and also generosity.

Yes. I went to help Nasir for a few months, just before I started on the MA and ever since then he has been very generous with his help, with materials or by teaching me how to make things. Kindness and generosity are so important.

That’s a perfect conclusion. Thank you.

Thank you, that was nice.

‘Some of my favourite times are spent just making something in the studio, even if that’s really rare these days. Fashion is sometimes so overwhelming.’