Phillip Picardi and his LGBTQ team are giving

Condé Nast an authentic queer voice. Meet Them.

By Raven Smith

Photographs by Brigitte Lacombe

Phillip Picardi and his LGBTQ team are giving

Condé Nast an authentic queer voice. Meet Them.

In a roundabout way, Them was conceived through anal sex. In July 2017, Vogue’s cover story featured it-couple Gigi Hadid and Zayn Malick apparently ‘embracing gender fluidity’ by swapping clothes. It was a heavy-handed and tone-deaf approach to gender identity that outraged millennial readers and forced Vogue to apologize: ‘we missed the mark.’ Only a week before, little sister online publication, Teen Vogue, under the digital direction of Phillip Picardi, a then-25-year old from Boston, had released a guide to safe anal sex, which said, ‘It’s important that we talk about all kinds of sex’. The use of ‘we’ here demonstrated the implicitly inclusive nature of the publication: peer-to-peer millennial discourse, rather than teacher-pupil education (albeit written by a millennial self-described sex educator). In a seismic shift, Vogue talking about millennials was eclipsed by Teen Vogue talking with millennials.

With Picardi overseeing its all-important digital output, Teen Vogue was pivoting from mini-fashionista editorial to voice of a new, alert, engaged generation. Typified by that sex-advice feature, Teen Vogue’s sincere lateral tone of voice and non-salacious practicality resonated, shrewdly harnessing the power of the most underestimated group on the planet: teenage girls. Vogue’s little sister was woke and not going back to sleep.

Within days, Picardi – who was increasingly being recognized for spearheading Teen Vogue’s record-breaking digital growth – was summoned to have lunch with Condé Nast’s artistic director Anna Wintour to discuss future opportunities. A kind of Condé Nast carte blanche. And so, the idea for Them, a next-generation digital platform produced by and for the LGBTQ community, was conceived. According to Condé Nast’s press release about Them, Gen Z-ers ‘support brands that take a stand on issues they believe in personally’ and ‘more than half of Gen Z identifies as queer’. A social-change-focused LGBTQ platform was an inevitable and savvy addition to the company’s portfolio.

Channelling Gen Z’s energy into meaningful audiencefirst editorial is now Picardi’s raison d’être. As chief content officer of Them (a role he has added to his continuing duties at Teen Vogue), Picardi is responsible for a team chronicling next-gen millennial stories and voices, harnessing andamplifying these expressions of change. Them puts LGBTQ identity politics front and centre as previously specialized social-media discussions punch into the mainstream consciousness. Them is a pastel-coloured rolling newsfeed of verbal and visual expressions of the modern (predominantly US-based) queer experience. Its stories showcase the intersectional narratives that have often fallen between the gaps of our worldview. It is a mix of earnest activism and bold optimism: a tender (and eerily accurate) self-care monthly horoscope sits alongside pieces questioning queer representation at the Oscars, fat-phobia in the bear community, and assessing whether ‘Ancient Egypt was totally queer’. The platform is an uroboros, receiving feedback as it’s transmitting; Them’s audience simultaneously absorbs information and responds immediately, with commentary that shapes future stories, adding to the endless reciprocal Internet conversation. A stream of consciousness from a generation of evolving thinkers, with ideas being processed and published in tandem, Them is a thesis developing in real time.

Earlier this year System asked London-based writer and creative director Raven Smith to interview Phillip Picardi, the man the New York Times recently labelled ‘Condé Nast’s 26-Year-Old Man of the Moment’. The first time in February 2018 during London Fashion Week the pair shared a pitstop high tea. For the second, a month later, Smith travelled to Condé Nast’s New York headquarters at One World Trade Center, where he also met and interviewed the Them team.

Phillip Picardi

Chief Content Officer

Part One

London, February 18, 2018

Raven Smith: OK, it is recording.

Phillip Picardi: So, I was reading that you had worked at Nowness and that you guys published a film a day.

A film a day, every day, for seven years. It was savage.

Looking at the media landscape now, I wouldn’t be able to identify a direct competitor to Nowness. There is probably more in the peripheral space. i-D does great artsy videos, so does SHOWstudio. Did you see the Gareth Pugh video they did last season? Oh my god, it is so filthy! It started with Olivier de Sagazan and Gareth Pugh layering themselves with moulding clay, painting a red phallus and then cutting through it so it looks like he was bleeding. It was shown in the IMAX theatre and the

whole audience was like ‘eeuww’.

I like that though; things don’t always need to be palatable.

It’s interesting, sure. Some people are like, ‘Why does it have to be palatable to be consumed?’

How do you find managing that within the context of Them?

Them is an interesting case study because I feel our mission has to be twofold. On the one hand, we are a queer staff, creating content for queer people and for queer consumption. On the other hand, we exist within this extremely normative corporation called Condé Nast. One could even say extremely white and normative. We see our mission as, yes, we are doing this for the queers, and then, what are we going to do to educate a wider audience about what we’re about? We can be ‘them’; we can be the LGBTQ community; we can be trans-youth. I think the best example of where we can be found is a video we did called How to Raise a Child.

What’s the story behind it?

I grew up in a pretty conservative Catholic family and my sister was always very strait-laced: Boston college, bottle blonde and married to a banker. One of her best friends is raising a kid who essentially sounds like they’re transgender. The parents thought he was theirson who wanted to dress in girls’ clothing, but there was actually more going on. I was inspired by this parent-child relationship, so we created a video with trans kids from all over the country interviewing their parents. It was viewed over 1 million times on Facebook, and the comments it got werevery touching. There were a lot of parents who said, ‘Thank you for this, I have felt so alone’. We felt we did something good for these trans-kids growing up, but also for the families who are raising them.

That’s brilliant. It feels like video is the big medium at Them.

We did another video series called Bedtime Stories. We invited queer peopleto bed, and the rule was, you can bring something or someone. This one couple – I believe they were genderqueer – brought a massive dick candle. They were burning it in the bed while they talked about having sex with women, and it was kind of amazing. Then we had a couple who met as a cis couple and then one of them started transitioning. So the straight guy is now negotiating with the idea, ‘Am I gay?’

How have your own life experiences shaped the way Them operates, its outlook, its editorial tone, its mission?

I grew up with three brothers and a very traditional dad, the type who came home at five and expected my mom to have food on the table. My brothers were hyper-masculine, super-athletic,

played a lot of sports, and that was just not my template, not how I was born.

Where are you in the family?

I’m the fourth out of five children. When I was a kid, it became clear to me that I was extremely different just because of my family dynamics. And my mum was often protecting me, but even in her protection, which I think she considered benevolent, she was always telling me to straighten out in certain ways to avoid being teased or mocked.

And your family were aware that you might be ripe for bullying?

Yes, my family was always trying to protect me from being bullied, but the reality of it was, I was just fine. They were maybe projecting experiences that they had gone through onto me. Growing up

it was very clear that I was gay. I would go into my mom’s closet, put on her Manolos, and walk around in her lingerie. For read-a-book day in first grade, I took a mini Spice Girls book and I had

a Spice Girls lunchbox and Thermos. I was like so gay.

‘I eventually just used pictures of half-naked men as my Myspace background, and changed my display name to: ‘I’m here, I’m queer, get used to it.’’

From day one.

When I came out at 14, I didn’t think my family would be surprised, but they were really shocked. I was shocked by their shock. These days, when young queer kids ask for advice about coming out, I say: ‘Tell your support network first and make sure that is not your family, so that you have somewhere to go when you’re out.’ I am sure most people’s coming-out stories are not easy. But my family reaction was to push me back in the closet; I had to lie to my little brother for months; I had to lie to my grandmother. A lot of it was sad and very unnecessary. But what came out of that is that I had to find my own voice.

Where did you turn?

I found myself to be more comfortable at school in that community, not relying on my family as much as my other siblings did. After a month or so of my mum not talking to me and my dad sending me to

a Catholic therapist and all this bullshit, I eventually just went into Microsoft Paint, took pictures of half-naked men from Abercrombie & Fitch catalogues, and made that my Myspace background.

And I changed my display name to: ‘I’m here, I’m queer, get used to it.’

A digital coming out.

Exactly. Like, ‘I’m going to show these assholes, I am not going to be silenced!’ Ultimately, I was out of the closet and had controlled my narrative, and I did so in a digital way, which is very relevant to my subsequent situation at Them.

How did people react at the time?

Basically, they were not hospitable to me existing and prospering in their school environment. The only thing I really knew how to do was just be true to myself and just stick to my guns. If it hadn’t been for my beginning and having been stifled and trying to find safety elsewhere I don’t think I would have been so comfortable in my own skin today. And so what I have learned through working at Teen Vogue, and hearing from kids over and over again is that there is this craving for

representation.

Tell me more about that.

Well, representation isn’t just important because it needs to represent the world in which we live, it’s important because it can really save a life – by seeing yourself somewhere you know that there is hope for the future and you can see a template for yourself. You can begin to map out your dreams and your future and your success; what you want from your career, your love life and your family. We need this for trans-people and the non-binary community, where the template for life is still very much being drawn. I think it is essential that we create media spaces that are welcoming and celebratory and honest about what life is like. And I hope that Them can be a true dedicated space for them.

People are shaped by their upbringings. Did part of your process feel like a reaction to yours?

We are all where we come from and that is clearly a big part of me. If you are ever at a big gay brunch with a bunch of queer people, almost everyone does their coming-out story. And that is how you get to know each other as something that you all have in common. I definitely think that documenting the queer existence with a thoughtful approach is important, especially for a mainstream publishing company like Condé Nast because we inherently have visibility and resources that make it easy for people to access our information.

Do you think in an ideal world that coming out will simply become less necessary?

I hope that one day coming out will be more of a choice; most queer people at some point are forced to come out, whether that is by other queer people or by straight people. I love that rebel spirit and maybe coming out will become obsolete, but I felt very liberated and empowered by my coming-out

experience.

I think it is very character building for everyone…

Someone recently asked me, ‘What is your advice for kids in the closet who won’t come out?’ and I was like: ‘Do your thing. If you’re not going to be safe when you come out of the closet or be evicted from your home or if your parents are going to stop paying for your tuition, those are all serious deal breakers that you should really consider, hopefully with a professional to help you think about what your next step is.’ You can’t force someone out of the closet. The reality is that coming out means less safety and security for some people. If you are coming out as a trans-person, if you are ‘passing’ and you don’t disclose that you’re trans in your work life, there could be violence on the other side of that closet door. It is not for anyone to say what you should do.

‘On one hand, we are a queer staff, creating content for queer people. On the other, we exist within this extremely normative corporation called Condé Nast.’

Where does your drive come from?

I don’t want to call this daddy issues, but people in my life expected less of me because I was feminine and gay and outspoken about it. They always underestimated me, shooing me away because my point of view was always too loud or radical. As a teenager, I felt ignored or stifled by the adults in my life. But the more I work with queer folks, discussing what ‘makes’ us who we are, the more I want to be wary of only framing ourselves in opposition to societal norms or power structures.

Did you always feel different?

I was always different, but there were moments where people in my life allowed me to taste the joy of just being myself. Like the Posh Spice doll my mom bought me but made me hide under my bed. Or when my little brother let me play the girl character in the video game without making fun of me.

Or my sister painting my nails bright pink. And my grandmother getting me the ‘girl toy’ at McDonald’s. It was also in the freedom granted to me by my parents – the unspoken understanding

that eventually happened that, no, they didn’t know what was best for me. That I had to find my own way

You faced backlash and acceptance. Are you driven by both?

I’m so tired of queerness being shaped only by tragedy, and queer stories being compelling because of their melancholy. Lena Waith said that our differences and our queerness are our superpower. I much prefer that. That in some way, we are a part of this community of extraordinary beings. I like to think that what makes me ambitious is that I was always a little different to the people around me, and I was always the only one. And now here I am, fighting for the opportunity to be surrounded by a bunch of people who are unique and exceptional in ways that are complex and worthy of praise and attention.

Fuck childhood tragedy, right?

I’m not, and I refuse to be, just a sum of childhood sadness. I come from love, and the understanding at a very young age that love is complex and hard to understand and doesn’t always say the right thing or doesn’t always feel the way you expect it to. You have to believe love is there, even if it’s deep down, and you have to be willing to fight until it surfaces.

What took you from your mum’s Manolos to Teen Vogue?

Back when I was 18, just before I went to NYU, I emailed the editor-in-chief of Racked, which at the time was a sample-sale blog, and I asked for an internship. I got hired after a phone interview.

I basically went from freshman orientation to fashion week back-to-back, which was quite an experience. Then, I was on fashionista.com, and I saw that Teen Vogue was hiring a web intern.

So you’ve always loved fashion?

No. In fact, when I realized I was definitely gay, I got really self-conscious and was really trying not to be interested in fashion. After I came out, I ended up in the magazine aisle and I picked up Vogue; I remember poring over it that day. Vogue was full all of this stuff that was just wild to me. I had never seen prices like that. I didn’t know that Chanel made clothes! I had no idea about this entire world.

I love that.

A friend of mine and I took a car road trip to go and see the Model as Muse exhibit at the Met. We drove like four hours there and back, just to go see this museum exhibit. But that was the power of Vogue and when I was a teenager, there was something in Anna’s editor’s letter or a feature in the magazine that was about gay marriage. I remember mainstream media not really showing us that they even recognized gayness or queerness at all. There was a line in the piece saying something like, ‘…the fashion community should stand behind LGBTQ equality’. And I remember it being burned into my retinas and thinking this is what it feels like to be seen and heard and represented. That is when I started having serious ambitions of working at Vogue. When I started working at Teen Vogue, I loved everything about the spirit of it and its slightly underdog status: we worked really hard and things were a bit scrappier compared to Vogue. We had less staff, we had to fight for access, so it was so much more rewarding. We had a lot of freedom too, editorially, to pursue our voices, which I loved.

‘I’m so tired of queerness being shaped only by tragedy. Lena Waith said that our differences and our queerness are our superpower.’

I get the impression that Teen Vogue changed massively, from being about what prom dress to wear into conversations that people were actually having.

Yes, when it first started, it was really designed as a magazine for a teenager who would later graduate to reading Vogue. But it’s important to remember the context at the time: that was when

Paris Hilton was on the rise, and so was The Hills, and Teen Vogue was part of these major watershed moments in pop culture. And that was epic, but it was a different time. Now we have this generation that has had access to the Internet since they were all born; they have unbridled access to so much more information than any other generation, so in many ways are much smarter. And their

perspective has changed. They are the most diverse generation in history. They don’t see themselves reflected in a lot of publications a lot of the time, so we had to shift Teen Vogue. Honestly, Teen

Vogue should shift every four years or so, like when you graduate from college, you need to recycle based on the incoming class’s priorities. So, what we did was just common sense.

I have heard you say that when you work on a woman’s publication, you don’t just talk about clothes and beauty. Can you expand on that?

Growing up, I also read GQ. It covered news and politics, sports and culture, but it’d always take fashion and grooming seriously as well. Then you’d read women’s magazines and politics never got the same real estate there. There was this dangerous assumption that women wouldn’t be interested in politics, so you put it in a men’s magazine. When I was growing up, so many girls were reading GQ, because they were interested in that perspective and point of view. Why weren’t young women being treated that way, too? That’s what I was asking myself.

Where did you first get a chance to push that editorial stance yourself?

When I was at Refinery 29, Mikki Halpin was the editorial director. She was launching the site’s news section. I was in the beauty department working on a story about cornrows, and I posted on

Instagram a photo of two white women wearing cornrows. Someone commented: ‘This is cultural appropriation and you are dumb if you think this is cool.’ So, I bought this book called The Encyclopaedia of Hair and read about the history of cornrows and spoke to Mikki and we developed a broader story out of it. I ended up meeting all these incredible women and I realized we can go deeper on beauty. It was a really formative experience and we went on to take as much pride in everything we did for beauty as the other teams were doing for music and culture. Treating one subject as importantly as another. When I was at Teen Vogue, I felt like we needed the same spirit of reporting that they had at GQ. That was my take.

Let’s jump to Them. It is such a striking symbol of our times, given that it is a Condé Nast title, and not an outsider indie. How did you pitch Them? Did you experience cultural issues with the people you were pitching to?

We were preparing for the mostly straight board meeting. I was given some insider info that the corporate contingent was concerned we were too isolationist, and that the brand would cater to too small an audience. We had to go show them the wide spectrum of queerness, where it touched on all lives. So we made a video that said, ‘This is not a niche culture, this is the culture. This is not a moment, this is a movement. This isn’t just about them, it is about all of us.’ And so the tagline became, ‘It’s about all of us’. For me that just means we’re all a little queer or we love a queer person or there’s a queer person in your family who we love.

How was the pitch experience itself?

There were so many people around the table, these suited executives, and it came down to the end of the meeting, when the CEO looks around the table and says, ‘OK, so what does everyone think?’ Everyone is raising their hand saying: ‘Do this, do this, this is great, this is now. This is the moment and we need to do it. We need to give this a chance.’ I mean, I have been at this company since I was 18 years old, so looking around that table and seeing all those people’s support was really beautiful. I actually went to the bathroom right after and cried, because I was so nervous and just so scared it was still going to get turned down. I’d been working on it for months, and I didn’t know what I would do if it didn’t get green-lighted. I was going to have to quit my job, and so I was thinking, ‘How am I going to pay my rent?’

‘I was given insider info that Condé Nast’s corporate contingent was concerned we were too isolationist; that we’d cater to too small an audience.’

So everyone at Condé Nast has been supportive?

People get really excited about working on Them. We had tech specialists and engineers raising their hands to work on the back-end of the website. We had creative people dying to work on it, even on the pitch.

Do you consider it a difficult job?

Sometimes it can feel hard. Having worked on Teen Vogue and Allure and given that Them is my third brand at Condé Nast in a senior position, I am realizing I’ve been given a lot of freedom and I am really grateful for that. I know for a fact that is directly because Anna Wintour was passionate about Them. When Anna is your boss, you are almost less afraid because you know this very important person is right behind you. I can talk to her about any story we publish. She has an incredibly open, reasonable mind about this stuff, so I am not afraid. Everyone has been open to this idea of pushing the envelope and having a small brand with the core notion of experimentation.

The level of freedom you are being given seems significant. Do you think this is unique to you?

I don’t know. I wonder what Will Welch would say to that question, because look at GQ Style, that is such a cool brand, and Bon Appétit is cool, too. I love it! Even Teen Vogue. The things that we are publishing at that brand, sure, 1o years ago you never would have seen. It’s hard for me to answer that question.

In terms of the stories you publish, what is your balance between editorial and branded? How many people do you have to please?

I have to please countless people! This brand wasn’t going to launch until we could prove the concept and line up advertisers. For about four to six weeks, Anna, myself and Pam Drucker, who is the chief revenue officer of the company, were meeting with CEOs of companies, getting them to sign NDAs, trying to get people on board. Of course, Anna and Christopher Bailey are really close, so Christopher heard about this first, then we took it to Google and then to Lyft. Luckily with every call we went on, people were excited about it, so it happened really fast.

What are Them’s business objectives?

Them is interesting because we don’t have ad pages or banner ads to sell like more traditional digital media. What we are looking to do is create customized content with a partner or find advertisers who are interested in creating something that will amplify the voices of the LGBTQ community.

Do you have a specific example?

Google helped us with the launch sponsorship, which was conceptualized around the theme of a talk show we launched on YouTube. Their team gave us great feedback and access to talent and great ideas for how we could really make those concepts sing on YouTube. Beyond that we are looking not just at content that exists on Instagram or just on the site, we’re also thinking what Them could look like as a film festival, a merchandise collection or an event series, for example. These are things that we will be exploring next year.

Are you continuing to make specific content with Google?

Yes. The rainbow check was our big thing with Burberry. With Lyft, we did a video with Tommy Dorfman where he rode around with a Lyft driver all day. He went to different stores, picked out products and then he took them to the Ali Forney Center, which is like the Albert Kennedy Trust here. For Google, we are doing interactive maps, because this year we have the mid-term elections. Do you know what that means?

Not really, but tell me and we’ll pretend I said yes.

Our presidential election is the big thing, but midterm elections are for Congress, and they are held two years later.

And that is for who represents each state. See, I’m learning.

You’re doing great! We are doing a state-by-state guide to LGBTQ equality, and then ranking the candidates who are running based on LGBTQ factors. Google said: ‘We’ll give you the Google maps for the project and you can work with Google engineers on building it.’ There is actually a team at Google called the Gayglers. It’s an LGBTQ group of employees at Google and they are so excited about Them. It is amazing to work with a partner who is for pro-LGBTQ legislation. They helped us launch a couple of YouTube shows. We launched a series called The Library this past week, and we’re about to launch InQueery, which Google helped us launch. It’s where we define terms and a queer lexicon. We’re just getting started!

‘There is actually a team at Google called the Gayglers. It’s an LGBTQ group of Google employees and they are so excited about Them.’

Part Two

New York, February 28, 2018

How do you define what makes a Them story?

I wouldn’t say our criteria are that clear. Being a new space, things are constantly being defined, which can get challenging. Sometimes we write about RuPaul’s Drag Race, but whenever we put that out on our homepage the entire team is like, ‘Should we really be doing this?’ We have a lot of conversations like, ‘Is this worthy of our attention or should we be spending our energy elsewhere?’

What’s negative about Drag Race?

It’s not negative per se, I think it’s great. But it doesn’t feel Them, for some reason.

For me, Drag Race is what other people do when they want to talk about queer culture.

I would agree with that. This space has been penetrated, sorry for the pun. I think there is a straight gaze that’s being applied to Drag Race, and maybe it doesn’t quite belong on Them.

It’s hardly a breaking story for the queer community.

Sure, and at the same time we did a piece on non-binary people talking about their identity and that was one of our top stories ever. We are more about finding stories that aren’t being told in the media that well.

When I went to Them online I was surprised, in a positive way.

Really? Tell me why

Because I thought, ‘Oh, it’s going to be all about queer issues and I know loads about that’, and in actual fact I was like, ‘Wow, this is all new. I’m learning loads!’

It has been fascinating, and I am learning a lot, too. You have to be really open, editorially. With Teen Vogue, I have a very clear instinct and direction – I can say yes or no really fast. But with Them, there is always a negotiation that involves multiple editors chiming in, and us having to agree on what’s the best way forward. It’s a very different way of working; it’s a lot more sensitive and collaborative.

It sounds nuanced.

It is incredibly nuanced. Aaryn Lang, who appears on Them’s video show The Library, talking about trans incarceration, said: ‘It’s great that we’re talking about this, but we should also be making space for trans-people to be happy, celebrated and beautiful, not just talking about their tragedy.’

Have any stories created a backlash?

I found a stand-up comic on Twitter named Philip Henry and he has a column on Them called Dear White Gay Men. I am not sure everyone understands his sense of humour. He did this piece on a Senate election where Roy Moore, a[n alleged] paedophile, was defeated by Doug Jones, a Democrat. Doug Jones’s son is openly gay and was standing behind his father when Vice President Mike Pence came to swear him in. Pence is very homophobic, and he was onstage with the openly gay son. Human-rights campaigners and several gay organizations were saying, ‘This is the resistance hero that we need’. Philip Henry’s take was more critical, as in: ‘What the fuck is he resisting? His dad is working in politics, shaking the vice president’s hand! This isn’t resistance, calm down.’ It was very funny and poignant, and a good example of how resistance can be co-opted by mainstream interests. Off the back of the piece our CEO and communications team received masses of hate mail. Philip’s Twitter account was dug through and people were sending me ancient Tweets he had written. So that was tough. Then we ran another piece about a trans-woman who confronted Rose McGowan; we had a lot of backlash over that one, too.

I think it’s really tough because whoever you talk to has their own vision of their part of the story. There isn’t a judgement-free lens.

It is tough, but when the language McGowan uses is deliberately transexclusionary… but I just hope she’s OK.

Women in the public eye get lots of shit.

I have mostly women on staff, as does Teen Vogue, of course. My close friend, Lauren Duca, was one of my columnists at Teen Vogue and her piece ‘Donald Trump is Gaslighting America’ went viral. For the past 18 months, I’ve seen the aftermath. Her private information has been posted publicly online. She’s had rape threats, death threats. Her husband has been smeared publicly. There is a level of critique and constant analysis of women that is so exhausting. After Teen Vogue published its anal-sex article, there was a backlash. I thought, ‘The fact that you guys are so upset about us teaching kids about anal sex just shows that you have so much homophobia existing within your communities’. I talked explicitly about how education is not encouraging sex; it’s about empowering and helping people to make decisions about their bodies that are wise, smart, and healthy. The level of critique was a lot for me to handle. At the same time, my wellness editor – even though she hadn’t spoken out about the piece publicly like me – was receiving significantly worse critiques and abuse. The only difference there is that she is a woman. Men feel that they can intimidate women, so they use their platforms to do that, which is just sick. There is absolutely a double standard. It is absolutely harder for women to have a voice and to have an opinion, while men

are given more leeway and are more protected, because men run these systems.

‘When Anna [Wintour] comes in and looks at the content, she’ll say, ‘That’s fine to do that, but where’s the positive, where’s the smile?’’

What does Condé Nast think about stories that ruffle feathers?

I’ve not heard anything back. Condé Nast has a long-standing reputation for standing by the editors. I am really lucky that Anna is my boss, so if there’s a problem she brings it to my attention and we have a conversation. I’m never being scolded; I really appreciate that about her. As the guardian of the editors here at Condé Nast, and the editorial voice within those boardrooms, Anna absolutely advocates our best interest and point of view, which is huge.

So, you feel supported by the entire ecosystem.

Yes, and that also trickles down to Teen Vogue as well. We’ve published things like what to gift your friend after she’s had an abortion. And that guide to safe anal sex. I didn’t fear retribution any time I published anything like that; in fact, the company actively reached out to us, to make sure we were OK because of the vitriol we got externally.

Let’s talk more about your rapport with Anna Wintour. From the outside, she is still considered a fairly daunting character.

I was initially daunted by her; she is the most successful, powerful woman in publishing. It is unequivocal – she’s an icon. There is no one else alive today I would look up to and revere as much as her.

Has she given you any specific advice?

Lots of advice. One time I was taking criticism very personally – I forget after which episode – and she looked at me and said: ‘You have to have a thick skin and you have to be firm in your convictions. When you publish something, you stand by it.’ It was really good to have perspective from someone who has lived through more controversy than me. When Anna focuses on Teen Vogue and Them, she always focuses on optimism.

Does that differ from your own perspective?

When we talk about the queer or marginalized communities, we talk about social justice, and can sometimes focus on the negative. When Anna comes in and looks at the content, she’ll say, ‘That’s fine to do that, but where’s the positive, where’s the smile?’ Especially with Them, she says: ‘Of course, these aren’t the best times for the queer community, but where’s the celebration? I don’t want it to be just doom and gloom.’ Her vehicle for that most of the time is fashion and it’s been cool to partner with her on that.

Do you sense that Them’s influence and culture could have a presence in corporate settings beyond your direct market?

Well, we already get asked to speak at corporations about how to help make their policies more LGBTQ inclusive. A lot of these companies are asking us, ‘What can we do for the LGBTQ contingency at our organization that would make them feel more included here?’

We’ve talked about representation at a boardroom level for non-binary transpeople. Can you think of any other examples where that is happening?

In other companies? My friend Janet Mock, who lives in LA, is a producer on the show Pose with Ryan Murphy. She started off as a writer on that show. Her life experience ended up being some of the most valuable in the typical brainstorming they were doing with the writers, so she was elevated to producer, which then influenced the way the show is at a broader lever: they are casting more trans-people, and how they are approaching trans-people’s lives in general. Jill Soloway at Topple Productions identifies as non-binary, and employs trans-people to work for her company. It’s interesting to see how the programming has changed for a lot of the shows they are working on now there’s literally different representation at the table. And that’s just the entertainment industry. Danica Roem’s election here in the US17 has put trans politicians on the map in an interesting way. I’m interested to see what her legacy will be and how she continues to shake things up as an elected official.

‘Sometimes we write about RuPaul’s Drag Race, but whenever we put that out on our homepage the entire team is like, ‘Should we be doing this?’’

Would you consider what you are doing as a form of activism? And is the new activism about having to play a different game? That’s a big question…

I don’t think that it is an either/or. It is vital we have people who are revolutionary, and who are intent on killing or overthrowing the system. But activism doesn’t have to exist in such binary terms. Constantly critiquing the system is also very valuable. Constantly pointing out its flaws, its hypocrisy, and making a platform out of that, will always be necessary. But for me that is not how I choose to exemplify my activism.

Do you think that the media can get too caught up in what’s wrong, what needs to be fought against?

Social media can be very reactionary, and we can be in our echo chambers, too. You know, we’re often talking about our traumas or our experiences, and often queer people are encouraged to air those experiences in a public forum. So we need to remind ourselves that we have a lot to celebrate, too, even if it’s just in being ourselves. Making a concentrated space for that is empowering.

An empowering space within Condé Nast?

I am sure that there are plenty of people who are very cynical about what we do. I don’t discount or ignore that cynicism, but if I can make this space a better place when I leave it – and by that I don’t just mean the corporation within which I work, but also the media at large – then I will feel that I have done a good job. It is not just about hitting my numbers and goals and making a platform for myself. It is about making this a more hospitable environment for the people after me, too. I am glad that I am able to represent young queer people in boardrooms of people who would normally be perceived to be inhospitable. I’m not afraid of telling the truth in those meetings. In fact, they have been very welcoming.

How does it feel to find yourself front and centre? As the face of the Them, as, I want to say, ‘the othered’? I can’t put it a better way.

I’m really careful about the opportunities I take to speak. If I can’t bring the Them team along with me, more often than not I will say no. You have to be careful about that kind of stuff. As a white, cis, gay dude my voice has been more or less heard. I try to be careful.

Why a career in media and not pure activism?

I’m still young; it could change. It could be politics next, I don’t know. Media is the template I began in, so this is the thing I wanted to explore and change. I am happy to be here – at the place that

produces the magazines I read growing up. I don’t know what the future holds. Who knows? I’m really into politics now.

Do you not think the new activism could be charming and lively rather than stoic?

Look at the kids in Parkland [after the mass shooting at their school]. I was just reading about this spring awakening in Parkland; a lot of them were theatre kids, completely unafraid of making a bold and audacious statement. When they go on stage, they deliver. They give you goosebumps when they talk; I don’t think they are stoic, but young and empowered activists today.

They are so perfectly placed and so in over their heads as well. They have this platform and they’re navigating it as they use it. There’s this unapologetic, kind of fearless clarity that they have, that I think we lose as we get older.

It is fascinating and so important to take them seriously and that’s what the world is doing, and I love that. It is wild.

It is wild and really exciting. In your ideal world, where do you see Them in five years?

It is hard to say, and I am reluctant to say anything about five years time, because look how much has changed in the last five years. My dreams for Them are mainly to do with having a big website and making it a daily site, posting 10 things a day and breaking news.

How many do you post at the moment?

About three times a day.

That’s loads.

Teen Vogue publishes around 40 stories a day.

‘Danica Roem’s election in the US has put trans politicians on the map. I’m interested to see how she continues to shake things up as an elected official.’

That is crazy. Were you overseeing that when you were at Teen Vogue?

As digital director, yes. For me, it’s more interesting looking at distribution from various data points. I’m interested in documentary-film work, and making something that is going to a film festival or doing events and working with community centres all over the world. If I have an ambition for Them, it would be that it can offer Them spaces in Russia or China, where LGBTQ rights are still being so fought for, and make sure that we’re lending our expertise, resources, corporate power and protection to the people who really need it. I would say that is my goal. A team across the globe. We have gotten so many messages from people who work for Condé Nast International, from all over the world saying, ‘We need Them here more than you need it there’.

One last question. We never really got to the bottom of what makes a Them story. How would you complete the sentence, ‘I know this is a Them story because…’

… it is not gay, not lesbian, not bisexual, not trans, but it is queer.

I have been an out trans-person in the media for five years. My introduction was through reality TV, appearing on the second season of The Glee Project. I started writing for Rookie shortly after that, and although I am now primarily a writer, it has been a pretty winding path and I’ve done other media work like speaking at universities and conferences. A lot of millennials and Gen Z are multi-talented: our lives and careers are more fluid than previous generations. What makes a Them story? It’s an authentic story from anyone in the LGBTQ community sharing their perspective and life experience. It’s a story that educates people, whether it’s to be more compassionate or more aware. It opens people’s minds from a perspective that maybe people haven’t heard before. It has a lot of heart. What makes it Them is us.

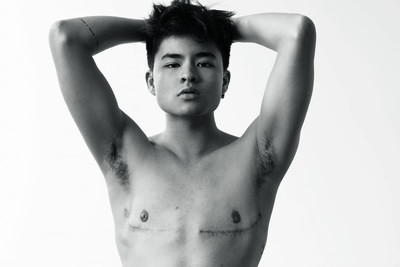

My career started as an intern at Playboy magazine, which might seem ironic, but it isn’t – the sexual freedom and firstamendment issues at the heart of Playboy’s editorial philosophy are very much aligned with a queer political and social ethos. I know at first blush it might seem that a magazine for straight men might be the least queer thing in the world, but if you dig deeper, there’s a lot that’s very queer about Playboy. It also bears mentioning that the magazine and Hugh Hefner were a bastion of early gay and queer rights. My time there was instructive and valuable, and in many ways was a natural foundation for what I do now. After a number of years at Playboy, I jumped over to Vice and became LGBTQ editor before coming to New York and joining Them. I had been interested in queer stories for a while and I was editing stories about trans-gender men and about the trans-community in politics, so I had already manifested an interest in that in my work.

What I love about millennials is the blurring of the personal and professional. Older people pretend they have professional and personal boundaries and then communicate in a way that means their personal relationships are not visible to other people. That’s how invisible centres of power form. It is good for people to be transparent. Yes, I am trans, but I also have an editorial and digital background, so that puts me in a unique position to engage in projects that push the envelope. Amplification and transparency, that is a really big value of mine as a journalist and editor – I want to do ambitious and groundbreaking things.

I am new to the Them team. I was working at J.P. Morgan before, which is obviously finance and a very different culture. As a person, I exist within grey areas, and so does my gender. At J.P., I didn’t have much room to express those areas, so I began keeping a blog during off-work hours, as a way to humanize transgender people for a cisgender, heteronormative audience. As I began connecting with others, I realized I needed to be in a work environment with people who thought in ways I do and desired to bring about change. I don’t fault the individuals I worked with, my co-workers were at times very progressive, but social progression at J.P. almost always hits a glass ceiling. When I hit that ceiling, it became the wrong environment for me. Over time, my writing evolved, becoming a much bigger deal than I ever could have imagined. Blogging transitioned into activism, my profile grew, and I was introduced to Meredith [Talusan]. Soon after, Phillip began following me on Instagram. I guess he liked what he saw because eventually I was hired to work with Them!

It would have meant a lot to the 12-year-old me to see people who are not only out, but also very unapologetic about who they are. It was hard to come to terms with being a queer woman because I didn’t see representations of brown people being queer or bi. At Them, we have so many people of colour in our content, so perhaps it is easier for younger people to imagine themselves as adults. I think seeing people who have made it to the other side, landing in adulthood, is reassuring. I think that there is value in having adult examples to follow.

I went to journalism school and came out as lesbian in my senior year at college. About four years ago, I came into my intersex identity. Identifying as two letters in the LGBTQI alphabet, I felt like I wanted to hear more of these stories and also have the ability to tell them first-hand. We’re really focused on quality video content. Like the Butch Please video that highlighted something people thought had been disappearing, but was actually just under-reported or forgotten. What’s interesting is how Them reaches people outside the LGBTQ community. Some of the comments on Butch Please say: ‘I am not queer, but I present more masculine and I have never seen myself represented this beautifully before.’

There was a lot of thought put into our pastel gradient design. You look at the rainbow flag and you see how it’s broken up and our idea with this gradient is to look more at a spectrum of colours. Looking at the small in-betweens and all the different people and bodies, rather than rigid segments. That is how more and more young people are feeling, one thing one day and something different the next. There’s a fluidity and we wanted something that represented intersexuality and a broad spectrum. That gradient is definitely Them.

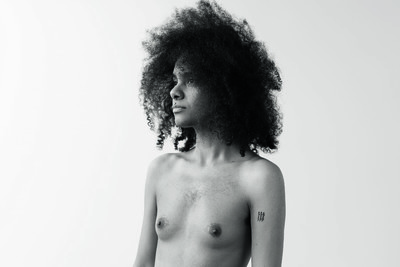

Growing up in a very small town in Pennsylvania, I was known as the boy named Rachel. I didn’t connect with the body I was in. Luckily, my parents were incredible, letting me cut my hair and wear the clothes I wanted to wear. When I was four I realized that I had hearing loss, so from a very young age I stood out. Less than a year ago I realized, or let myself realize, that I wanted to transition. I was like, ‘How did I put up with that for so long?’ So, of course, I immediately wanted to preach to the world and let people know this was possible. Even if I wasn’t comfortable at the time, I knew this story needed to be out there, people needed to understand that bodies like this exist. In the future I hope that people can see themselves as their own representations, and that they have the safety and privilege to do so. You don’t need to see people like you in big movies, you can just look in the mirror and see yourself and know that you exist and that can be enough.

I’m Muslim and I’m queer and those two things have been very important parts of my identity because there obviously isn’t a lot of transparency with queer Muslims; there’s a lot more silence with the experience in those communities. Writing the astrology column for Them, I just feel grateful that I can write something where I don’t have to constantly go back and self-interrogate. I am not being grandiose, I am not saving anybody, but it’s a difficult time for an anyone who isn’t white or cis or straight, and with astrology, sometimes people need something that’s bigger than their identity, something that’s more universal, so they can just escape. I was raised by Marxists, so I understand the anti-corporate mentality, but I also think it’s important that Condé Nast has created a space where they can pay a ton of young LGBTQ creatives and give them a platform. What I get paid for my astrology column allows me to survive.