How fashion finally landed upon Jun Takahashi’s world of Undercover.

Interviews with Kim Jones

and Nobuhiko Kitamura

Text by Tim Blanks

Photographs by Norbert Schoerner

Styling by Jun Takahashi

How fashion finally landed upon Jun Takahashi’s world of Undercover.

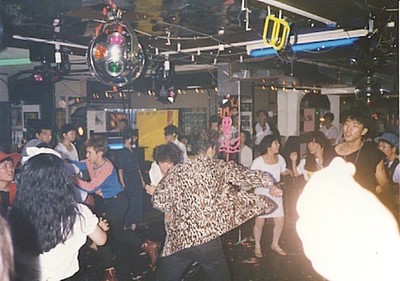

Jun Takahashi is unafraid to dive into the unknown. Travel into his Undercover world and his clothes appear, season after season, like answers to questions you’d never thought of asking. They have meaning, symbolizing his fearless desire to upend preconceived ideas and almost force you see the world in a new way. Indeed, since launching Undercover in 1990 in Tokyo and opening the now-legendary store Nowhere in 1993 (with Nigo and Hiroshi Fujiwara), Takahashi has actually been altering the grammar of fashion: marrying what we now call streetwear with high-fashion detailing and quality finishes, all contained in avant-garde, high-wire concepts that are both deadly serious and airily light-hearted. Add in his long-standing love of collaboration and the Undercover ethos seems to encapsulate the current fashion moment.

And the perfect time for System to go Undercover. So, to Tokyo, whereJun Takahashi caught up with his mentor, ‘brother’ and fellow designer Nobuhiko ‘Nobu’ Kitamura, whose label Hysteric Glamour triggered his love of fashion. He then invited a visiting Kim Jones over to Undercover HQ for a chat about how Japanese streetwear has always inspired the new Dior Homme designer’s work. Meanwhile, in Paris, Tim Blanks spoke to Jun and deciphered his most recent collections the day after the final Undercover womenswear show (for the time being), entitled We Are Infinite. Which photographer Norbert Schoerner then shot in an apocalyptic Tokyo, as part of a larger portfolio documenting Jun Takahashi’s world – taking in everything from late-night karaoke to early-morning jogging.

‘Wow, you know my Undercover

collections so well!’

Jun Takahashi and Kim Jones

in conversation, March 16, 2018.

Moderated by Norbert Schoerner

Kim Jones has loved Undercover since his student days in the late 1990s. So while he was visiting Tokyo in March – after his departure from Louis Vuitton, but before the official announcement of his new role as artistic director at Dior Homme – System invited him to stop by at Undercover HQ to see his friend Jun Takahashi. Their ensuing conversation reveals a deep-rooted mutual respect and examines how today’s streetwear has its origins in the (sub-)cultural exchange between London and Tokyo.

Kim Jones: Back in 2001 when I was at college, I was helping out Michael Kopelman at Gimme Five with Hysteric Glamour. I was in the warehouse just packing boxes and doing stuff for them. There would be a catalogue with all the new season’s stuff and I just remember seeing Jun’s stuff coming in and thinking how fucking cool it was – there just weren’t clothes like that around. There was that punk element with lots of modern stuff. I’ve still got the platform shoes.

Jun Takahashi: Which ones?

Kim: They are bright electric blue with the checkboard plastic over the front. I never wore them because I love them so much; I’ve had them in the box ever since. I think it was Spring/Summer 1999. I’ve got all my Undercover stuff in storage because it goes way back. Michael was always really kind and would let us order stuff; he was really generous. We would look at things and enjoy the detailing. Small Parts was one of my favourite ones. You couldn’t really get any Undercover stuff from anywhere apart from directly from Japan, so people would be like, ‘What are you wearing, where’s that from?’ And people just couldn’t work it out, because it was that mix, I hate the term streetwear, but it was an element. It was fashion, and if you released all that stuff now, it would still be really relevant, that’s the thing. I was talking with Fraser Cooke about it and we were saying that the old Undercover stuff is just as modern now as when you first did it – and that’s a really great thing. I remember when the boxes would come in with the orders and everyone was super excited and would just sort of rip into them finding their things. When you saw all these amazing things that you were doing, or Hiroshi or Nigo. It was more interesting to look at – nothing normal or typical. There was Helmut Lang and Margiela, which I loved, but this was just a completely different way of thinking, the attention to detail, the branding on everything was just so strong. When I started designing it was something I would always think about, like the detailing on a zip pull. In luxury, you can obviously do those things in quite an extravagant way, but the starting point was your stuff. I’ve got a grey Small Parts jacket and whenever I wear it, people always ask me where I got it from, because it’s just so relevant.

Norbert Schoerner: Michael Kopelman had such a key role, connecting Japan and Europe, and the same with Stüssy the other way, and somehow, he doesn’t get the credit for it.

Jun: He is very important. Kim, so when did you come to Tokyo for the first time?

Kim: I came in 2001 and I had just graduated. I had £200 with me, my sister had got me a flight and hotel room for a graduation present. I remember walking around and it was quite difficult because there weren’t that many foreign people here and your phone didn’t work and there were no English signs. It’s really changed now; it is really easy to get around and do things. I think I was so shell-shocked that I don’t think I liked it very much because I didn’t know how to deal with it. But the second time I came out, I completely fell in love. I don’t think I was prepared the first time; I’d been looking at Boon magazine and had all this shopping in mind. I was still working for Michael when I left college, he had given me some addresses, but I was walking through Harajuku on my own and I didn’t really know where to go. Now you can just type on your phone and find a shop, but it was very alien back then; it was like you were in the future. And I think the yen was really strong against the pound, so I bought a pair of socks from Undercover and a T-shirt from Bathing Ape and that was it.

Jun: In 2001?

Kim: Yes.

As are a foreigner coming here, you are either shell-shocked or completely mesmerised. How is it for Japanese people leaving Japan for the first time?

Jun: I went to London for the first time in 1991 and I was already into punk and everything. I went to London with Hitomi Okawa. We travelled together and then she introduced me to Michael, whose house and office we visited together. We also went to his Christmas party and met Michael’s friends.

Michael and Hitomi took me to the shops. We didn’t have Internet and he told us, ‘So this is where punk fashion was born’. It was very impressive.

‘I was packing boxes in the warehouse, and remember seeing Jun’s stuff and thinking how fucking cool it was – there weren’t clothes like that around.’

Kim: How did that affect your design?

Jun: I was already influenced by UK culture and fashion but when I went there, I felt it myself and that made a big difference. At the time I was also learning about Comme des Garçons and Margiela, so everything from the UK and all those different elements influenced me at the time. Street culture and everything. All different things were interesting me.

What about Paris, did you have a relationship with Paris?

Jun: At the time? I was not so interested in Paris. I never even thought of working in Paris at the time.

Kim: Me neither. The only reason I did my second men’s show in Paris was because there wasn’t any menswear in London Fashion Week and they wouldn’t let me show on my own. And I thought, ‘Well, if I am going to do a proper brand, then I have to do it in Paris where there is a men’s week’. It cost a lot more money, but I just thought that you have to think big. I never really thought about it; I just did it. It was more challenging, but it helped me get where I am now, I guess. You have to go to the places where people do and see everything; you can’t expect everyone to follow you when you are just starting out. It’s much easier now with all the digital communications, Instagram and whatever, but back then you might get a little article in a newspaper or magazine. And people were seeing things six months before, but then you’d have to wait to see the full collection.

Maybe it is good to be out of your natural environment as well, because you have to work harder.

Kim: I love doing shows; it’s my favourite time and the nicest part of the job I think. Everyone leaves you alone, because they know you’re really busy and it’s quite stressful, but you can really be with your team and enjoy it. I love working with people and that thing of not having other people coming into the studio and asking questions all the time. We might have the seating-plan meeting, but that’s only five minutes and the rest of the time is really creative.

Jun: I agree. My main job is to prepare everything for the shows. I assemble all of the elements of a show, such as its world view, the design and music, at the same time. I work on the basic design quietly alone, while listening to my favourite music. This is when I’m happiest. At that time, staff members leave me alone, just like yours do, Kim. My greatest pleasure is the process of expanding the theme and world view that I have visualized.

Kim: Were you scared when you first showed in Paris?

Jun: It wasn’t too scary because I had been doing shows for 10 years in Tokyo, so I knew what to do, but you never know what the reactions will be. Japanese people don’t really criticize the shows; they just say, ‘Oh, great show’. They don’t say much more than that. People say things aloud more in Europe; they criticize. I didn’t know what to expect, how a Tokyo designer would be perceived in Paris. And especially at the time, my work was really a mix of street and high fashion, so I didn’t know at all what people would think as it was not as popular then to mix those two. So I was scared. The first show in Paris was for Spring/Summer 2003. The collection was called Scab and we held the show at the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs. Actually, I didn’t originally intend to hold a show in Paris; I didn’t even dream it could happen. But while I continued showing in Tokyo, I developed this desire to present my work to more people. I decided I wanted to hold a show in Paris a few years before I actually debuted in 2003, I think it was 1999, so I went there to talk to local media. The reactions of the people I met at that time were not so good, even if we did discuss a project for a big feature in one magazine. But when I got back to Japan they flatly said that they’d never made such a proposal. I was really depressed and gave up on doing anything in Paris for a while. Then Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons came to see my show in Tokyo and the next day, I received a fax from her, saying: ‘Why don’t you hold a show in Paris? I think it is about time.’ That was what made me decide to move the show to Paris. Also, I felt my work in Tokyo had reached its limit. So I went back to Paris to prepare for showing there and get everything in place. All that was left was to believe in the work and present the designs that I had been working on up until then. Fortunately, Rei Kawakubo and Adrian [Joffe of Comme des Garçons] had told the media in advance that a brand called Undercover from Tokyo was going to show and urged them to go see it. That’s why a lot of media came to the very first show. There were differing reactions, but I remember being really delighted to be able to listen to their honest feedback.

‘I first came to Tokyo in 2001; my sister had bought me the flight as a graduation present. I remember struggling because there were no English signs.’

It took you out of your comfort zone.

Kim: I had the naivety of youth too, I think. I was just running around without thinking and luckily people responded well, but when you are young, you don’t think so much; you just do things. People reacted well to what I’d done, and I just thought I should keep on doing it. I never really wanted my own label; I always wanted to work for people, because I prefer that. My dream was to work for Louis Vuitton because when I first left college I did some graphics for them and I saw the facilities they had, and I was like, wow. And I got the job 10 years to the day after graduating, so it was a nice thing in my career. But then you get the seven-year itch and you have to challenge yourself or you can get quite complacent – and I like to challenge myself. I loved working there. It was a brilliant experience and I still have a great relationship with everyone there, but I wanted to challenge myself with something else, so I thought it was a good time to change.

Jun: How did you feel about working for Vuitton only 10 years after you graduated. It sounds really fast. How did you get the job?

Kim: I’d stopped my label and had been working with Dunhill for three years when I got a call from Vuitton. I went for an interview and did a project for them, and then I got the call to say I’d got the job. I was so happy I was crying. I think it was the right time for me, because if I’d got it earlier I probably wouldn’t have done such a good job; I wouldn’t have had enough experience. So it was just that thing, right timing. I went in and planned out what I would do for the first collection, and it sold really well and people liked it. It felt like the right thing. What I like about Vuitton is that essentially it is a luxury luggage brand and I like travelling and seeing the world, so it fitted in with my lifestyle. I think that when you can fit things with your lifestyle, then they work very well. I have been to lots of amazing places looking for stuff for collections, and I’ve seen the world.

Kim: Anyway, tell me more about your first show in Paris; that was the ‘scab collection’, right?

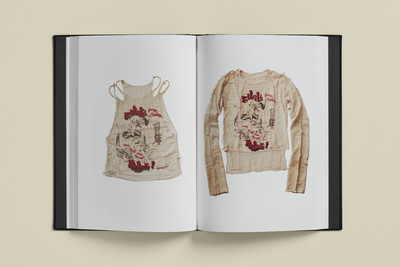

Jun: Yes. It was inspired by this genre called crust punk or crustcore. It was a branch of hardcore punk that was all about vegetarianism, animal protection and DIY. I was inspired by the patched outfits worn by these crust punks. Their ragged, patched clothes looked very elegant to me. For the collection, we handstitched a vast number of small pieces of cloth together and the name came about because the small strips of cloth looked like scabs.

Kim: I remember those jeans – they were sewn from millions and millions of little patches. It’s that level of detail that you so rarely get with designers. You can do that at Vuitton though and I think it’s something that you do, too. It’s about being able to do things at a level you really want to do them at. And I think one of the good things about Japan is the high level of production that you have here. When I had the Kim Jones label, I produced my stuff in Japan because we sold to more stores in Japan and so it was cheaper to import it from Japan than to make stuff in England. Whenever I see good young designers in the UK, and I speak to a lot of them, I always try and point them in the direction of good manufacturers or people who can help them to make their products, because that is the biggest challenge. In Japan, you don’t have to do huge quantities and you can have this exceptional quality, with fabric making too. In England, there are only a few fabric makers left; it’s a bit of a sad state of affairs. You just have to look at the world rather than one place.

Jun: Even in Japan, lots of factories are closing, the fabric places… But as you say, the quality is good, but not so much the shoes anymore. It is getting harder and harder in Japan because all the

shoemakers are disappearing, with no new ones to replace them.

One forgets how big the Japanese fashion market is, the domestic market. I don’t think people in Europe or America think about that so much.

Kim: I think it’s interesting when brands that aren’t perceived as being that big in other countries then come here and they’re really popular in Japan and have a huge store. It’s really crazy!

Jun: Japanese customers are really addicted to fashion; they catch all the new trends. I think Japanese have foresight for music and fashion down through the ages. They have a talent for finding talented artists earlier than anyone else and expanding their art. I think Japanese are unchanged in this regard.

Kim: Also, certain brands like Undercover become cult, so they have a loyal following who will always be there. Those people understand what the brand is and what it’s for. It’s really nice when people just love what a brand is and just support it constantly. You see that a lot in Japan, not so much in other places.

Jun: The growth of the Internet has meant that more information is available and that’s eliminated the difference between Japanese and overseas followers. And thanks to the spread of the Internet, more people around the world have come to understand the history of Undercover. I feel like recently the brand is finally being understood.

‘I received a fax from Rei Kawakubo, saying: ‘Why don’t you hold a show in Paris? I think it is about time.’ That was the trigger.’

As a Japanese designer, do you think about the Japanese market and the Japanese environment more than the audience in Europe and America? They’re very different I would think. Or do Japanese designers want to work worldwide?

Jun: Now we have access all around the world, but in the past, it was just about Japan. To begin with I never really thought about selling my clothes outside of Japan. I just never thought about it. I only started realizing I could go outside the country when I found people outside of Japan wearing my clothes or they came to Japan and I saw customers from abroad.

Kim: It’s quite funny though because it is very hard to find imagery of Undercover before you started showing in Europe. I have old Boon magazines and a copy of the Undercover special of relax magazine, but it was very underground. So when you did the book, people were like, ‘Oh my goodness this is incredible!’ A lot of people in the Louis Vuitton studio went to buy the book and thought it was really amazing. It was a secret until the book came out. It’s like the first chapter of what you had done, and then people started to get what it was really about. You know, people like Tim Blanks who really loves Undercover and puts it as his number one show each season. That’s amazing when you think there are all these other big companies advertising and paying a lot of money to work with these websites and there you are at the top!

Jun: Tim understands everything about the cultural background that I have and we connect really well, so it is lucky. He doesn’t look just at the design of the clothes; he sees fashion from so many

viewpoints such as the designer’s background and the world view they incorporate into the design of their clothes, why they show their collections when, as well as viewpoints such as the global situation and political background when they put on their shows. In particular, sources of inspiration for Undercover are mostly elements of music and art. Tim has such a good knowledge and deep understanding of them, so he understands the world view that I present much more deeply than other journalists. I also think he believes in the dreams and hopes that fashion embraces.

Kim: He is one of my neighbours in London, not that I get to see him that much. He understands a lot of things and there are not many people who do…

Jun: He is English, too?

Kim: No, he’s from New Zealand. But he escaped as soon as he could!

Jun: He used to be a music writer?

Kim: Yes, and he understands everything and won’t pass by anything without giving it a really proper look. I think it’s really important in life to do that. Michael Kopelman was someone who taught me how to work with people and how to be generous with people and how to be supportive of the team you work with. And you learn different lessons from different people.

Jun: We are from streetwear backgrounds, but recently people in high fashion are starting to understand us more. Street culture is having a big influence on fashion worldwide at the moment. A majority of designers are incorporating this trend superficially into their design, but some of them, who, like me, have been influenced by street culture since their childhood, do it in a much deeper way. I think Raf Simons, Takahiro Miyashita and you, Kim, are among those who get it. I started design when Harajuku culture was catching on in the first half of the 1990s. The generation of designers like Virgil Abloh, who were influenced by the Urahara fashion that I created with Nigo, are active in the frontline today.

Kim: I would never call what you do streetwear because the level of detailing and the design goes too far. Street for me is a sweatshirt or a pair of simple pants. That is not what you do, and it never has been. Especially around 2000, those collections are some of the most important things I have ever seen in my life in terms of going beyond details and about the way you put things together. Do you remember all the punk plaid stuff and the masks? I remember being completely blown away because I was still at college and it was just so far forward; there was nothing else around like it.

Jun: You know, for me, designing graphics for T-shirts is work on the same level as designing an elegant dress. That’s what my philosophy is all about: designing between street fashion and sophisticated fashion. So for that collection, we made tartan from many different materials and combined them to create a single piece of clothing, for example. Buttons, back cloths, tags, even shoe soles were made from entirely different materials but the patterns on them were the same. For the show, the models’ faces were painted in check patterns. I named the show Melting Pot with the idea that we are all humans although races are different.

Kim: It’s about loving different things and seeing how they work together. And all those Sk8thing T-shirts you did in Spring/Summer 2001.

Jun: Wow, you know my Undercover collections so well!

Kim: Because you did all the re-editions recently and I rebought the T-shirts I had lost. They look so modern still; they are just timeless and that is really nice. I still have all my Small Parts sweatshirts

with the hotdog. Mixing around the fronts and backs, that sort of customizing before everyone was doing personalization in things. The actual pattern cutting and thought processes behind all that were really impressive, too. The fact that you could buy all these things and put them back together differently – you’d have like knit sleeves on a denim jacket or a parka. It was really cool.

‘Designers incorporate street culture superficially into their work, but people like me and you and Raf Simons have been influenced by it since childhood.’

Jun: Design is like playing around with toys. I enjoy it, so maybe that is what leads to good creation. I’ve always thought that unless a designer enjoys developing designs, nothing good will be produced. If it becomes too much business and work, then maybe I wouldn’t be able to create such things. I know Vuitton creates a lot of good stuff, but was it difficult to work there? You didn’t find it hard working in such a big company?

Kim: I had such a nice group of people in my team; they were really there with me, and as long as you involve everyone every step of the way, you know you will be OK. It was difficult because there were lots of changes and you had to get used to that. When they changed, it would take the new person quite a while to get familiar with things. But I would talk to everyone; I’m not a snob. It was only if someone had done something awful that I would have no time for them, because I think that’s the best way to deal with it. But you know, I like to work with people and there were lots of really great people who I worked with. I understood that a pre-collection was more commercial than a show collection, so the show collection was where you could have really good fun and just make it yours. We’d have briefs for different things, like making a titanium monogram, where the real challenge was to make it look as metallic as possible. So, we would challenge each other and make things really interesting. Of course, there were times when things were harder to deal with, but then that’s the same when you have your own company and you’re your own boss. I’ve done both jobs. People

keep telling me that if I started my own label again, then I’d sell tons, but I like working within a structure and seeing really big growth; that’s what’s exciting. I like working with the best materials

in the world and having the best people to make them, and that for me is a joy. It is very different to being in Japan where you have access to that anyway. In Europe, it takes a while for an independent designer to access facilities that can make such good stuff. I love working for a brand, because if it was a type of art, it would be pop art. That is an interesting way to look at it because it is so global, so much about lots of people loving it because it is so big. You have to look at it through that lens because it is not avant-garde; it’s got to be real, and pop art is real.

What about running your own company, Jun? Do you get involved with the business management side of things or can you stay away from it?

Jun: Yes, I do have to make final decisions, but for the financial stuff, I have my younger brother and other people working on it.

Kim: People you can trust, that’s good.

Jun: In the past, I had other people working for me and they did bad stuff. Now I have a family member who I can trust helping me with the financial side of the business, which I’m really bad at. This means I can concentrate on the design work that I am good at without worrying about the extra stuff.

Kim: That happens a lot in fashion. It’s hard to find good partnerships.

‘For me, designing graphics for T-shirts requires the same level of work as designing elegant dresses. My philosophy is: between street and sophisticated.’

Jun: It must be really fun to work on something like Vuitton, which has a history and all these archives you can work with. I think that must be really interesting

Kim: There wasn’t really a clothing archive, but there was an archive of the history, so good things that you could take as references. I would always start each collection at Vuitton with a book on their company’s trunks throughout the ages. So you would see a trunk that went to India for a maharaja and another that went to Africa. Then you would read the story behind each one and our research for that season would come out of that. There was the whole thing of the journey and travelling, and you could create a story with all of that. I also like the idea of what things will look like in 100 years. Like when we did the see-through trunk with the Chapman brothers. The fact we even worked with the Chapman brothers is quite fun and quite sick, but it worked super well. Working with Hiroshi was a really great thing, too, because he is one of the biggest buyers of Vuitton in Japan, so it made sense. I don’t like things when they don’t make sense. I think there has to be authenticity, so when we worked with people, we would look at the history and see if there was anything we could do a collection around. I didn’t dig too much into the Vuitton archive at first, because I always wanted to find something new each time.

Jun: It is fascinating to take something from the past and to make it your own way. Over the years we have interacted with many artworks and artists, like in 2015, when we used Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights for Spring/Summer and Michaël Borremans for Autumn/Winter. It is so interesting that you worked with the Chapman brothers.

Kim: We did it twice. I love Jake and have known him for quite a long time. I went to the Himalayas for research because there was a story in the archive about travelling through the Himalayas with these trunks and there were all these weird animals. So I thought, who can draw weird animals better than the Chapman brothers? That was why I got them involved in it. It was that kawaii scary vibe I was interested in. Isn’t there is a different word to say ‘scary kawaii’?

Jun: Kowaii. I am going to interview you now! You took me to the Vuitton office once. Did you go there at the same time every day?

Kim: I would be in about 9.30 to 10, but I’m not someone who can be in the office every day. You need to be out seeing stuff in order to give back. When you work in a big company, you work with lots of people and you have to give them autonomy and the information they need to work, and you have to look around. When I first started, I was there all day every day, but then I realized that I didn’t need to be there all time, that I was more useful when I was out doing research and finding stuff to take back. It depended though; sometimes you’d go on press trips and all these different things. It was different all the time. What is weird now is that this is the first time in 10 years that I haven’t had a schedule for the next two months. I’ve been really busy, but it’s nice to have no structure. Wednesday I stayed in bed and watched TV with the dogs and that is a real luxury for me. You just have to work it how it is. Obviously, when you’re working for something big, there is a lot more press going on; you might go open a store in Hong Kong or Tokyo. We would use a lot of fabrics from Japan, so we would come here a lot. It’s a great place to do research and get inspired. Last year I was coming virtually every month because I just love being here and I always get a ton of ideas. Plus, the market changes here and as it is the leading market, it’s great to buy cool new things here. When you see what is popular in Japan, you know what will be successful worldwide. It is just a more mature market.

Do you see that too, Jun?

Jun: Are you sure it is like that? I am not sure, maybe now, but not in the past.

Kim: Jun, do you have an archive for everything you have made?

Jun: Yes, not so much before 2000, and I don’t have anything at all myself, but in the office, we have lots of stuff. After we started doing the Paris shows, we started doing archives properly. So you personally probably have more than we do!

Kim: I remember the hamburger collection and the hamburger shorts, and I’d wear it with Vans and a sweatshirt. That was my favourite thing, in olive green. I will have to find it all. I’ve kept every pattern of my stuff, but I gave a lot of samples to friends, and I have a list of who’s got what just in case I need to go and get it. I just gave them to close friends who I knew really wanted them. It was impossible to keep it all; I didn’t have the resources at the time, but I also like to move on. But it is nice to make reeditions now for young people, because it is 10 years since I finished. Like when you did your anniversary re-issues, it was so nice to see all those things again.

Jun: Some people said we were doing the same thing again, but it was a really good way to present our history.

Kim: Completely, and a really nice way to celebrate what you’d done in the past. I think it is important to do that because a lot of designers lose their work. Margiela is everywhere again now; he did such amazing things.

Jun: This season was really amazing, for sure.

Kim: You could do a really nice museum exhibition – that would be amazing to see.

Jun: Maybe outside of Japan, because we already did that for our 25th anniversary here. We are a small company, so it is difficult to find a place to do it.

Kim: We’ll have a think, right?

‘When you see what is popular in Japan, you know what will become successful worldwide. It is just a more mature market here.’

Jun: Are you still living in Paris?

Kim: I have a place in Paris, but I work between London and Paris, because London is where my life is and where I need to be; it is part of what I do. I am excited about change; it makes you nervous, but that’s a good thing. It is nice to look at things with a different approach. You go through a phase where you are really into something and then you’ll look at something else, and I think it’s nice when designers do that. They are challenging themselves and that’s very important or you get bored.

Jun: Exciting news about Dior Homme. Can I come and see your first show?

Kim: Yes, of course, I think it’s on June 23. When is yours?

Jun: We are waiting to confirm.

Kim: Let’s keep in touch! Whenever you’ve invited me to your show, I’m normally not in town; I’m off visiting fabric suppliers, often in Japan. The fabrics here are super expensive but super amazing. I would quite like to live in Japan. I would like to travel around Japan, too; I have been to a few places, but it is always a rush, and I would like to see things properly. There is a lot here to see. I went to the theme park near Mount Fuji, and it was only rollercoasters. I was so scared because I am so scared of heights!

Both of you work so much, do you ever have any time to do something outside?

Kim: We are lucky in Paris because we get a summer holiday, which is long.

Jun: Weekdays I work until seven and then I go home, and weekends are off.

Kim: When you know how to work you can sort of pace it, but when you are working for these big companies, there is a lot of work to do, so it can be quite relentless. You need to make sure you book time off. I don’t really eat in the evenings because I eat at work, but then I go home and watch some TV to take my mind off things and then go to bed.

Jun: It took a while to do it, but now I can switch off after work. Even if I go out with friends of mine who are designers, photographers, musicians, and actors, I never talk about work at all. The only people outside the company who I talk to about work are people working with us on shows and, once in a while, my family. When I am off, I do nothing basically. I am just an ordinary father. If I had no time to spend with my family or friends, I wouldn’t be able to make the distinction between work and private life

Kim: In Paris I don’t know so many people, so it is very quiet for me. I work and go home, but when I am in London, I’ll have dinner with someone or do stuff. Because I have done my job properly you are allowed to that; they respect you and allow you to do that. And when you’ve put so much in, it’s important to make time for yourself. The company knows that’s important.

Jun: When I last visited you in Paris, you were looking for an apartment. Did you find one?

Kim: I got a really nice one actually, on Place des Victoires. You can shut the gate behind you and you are just at home. I know other designers, but if you are in Paris, you are there to work. As I mentioned just before, in London, I have more of a life. I don’t want to go back every weekend on the train, because it gets really monotonous. I like to make sure I have a proper work-life balance. The Eurostar is really amazing though.

Jun: I would like to live in London for some time.

Kim: It is a nice place to live. I live in Little Venice and it is really nice. You kind of get these pockets in London. I wanted somewhere with a garden, so the dogs could run around and not bark at the neighbours. I like having my friends nearby and going shopping. I like to choose my own shopping; I like to do stuff myself. Not have a housekeeper. I love walking to places. I have a driver, but that is a business thing. I’ll walk all the way to Soho and have my music and you can look at everyone. I don’t like having my photo in lots of things because then more people know you and stop you… It happens more in Japan where people stop to have photos with me. Of course, I will always do it because they are potential customers.

Jun: For me, it is just maybe around Tokyo, but as a designer I am not that well-known.

Kim: Undercover is the perfect way to describe how you are. You can live your life in your own way.

Jun: In Paris, no one knows me! Even when I go to shows in Paris, I never get noticed.

Kim: That is a good thing. I made a mistake with the Supreme thing and hated going out. I looked really fat in that picture, so have been on a diet ever since! It’s like when you’re doing a show and

you’re locked in for days, drinking Coke and eating what is there because you are starving. It’s really hard to think about. Would you ever think about joining a fashion house if you were approached to join one?

Jun: I would love to. But of course, it depends who.

‘Undercover is the perfect way to describe me. In Paris, no one knows me! Even when I go to the shows in Paris, I never get noticed.’

Kim: I can see you doing an amazing job.

Jun: No one’s ever offered though!

Kim: Just one more season of Tim’s great reviews!

Jun: Maybe because of the language barrier.

Kim: I think that people look more at the talent and experience. My French is terrible, but I get by. I understand everything, but just speaking it is very difficult. But you make it work because communication and harmony in your team is so key. When you are doing this job, you cannot do it on your own. You are the starting point, but then you need everyone else who works with you. People say you can collaborate too much, but I always say, ‘But you collaborate every day at work’.

Jun: From the beginning, I was collaborating. I like to collaborate. Whether it’s with Hiroshi Fujiwara, Nigo, Uniqlo or Nike, one plus one can produce four because you’re working together with

people and companies that have something you don’t have. For my runningwear collaboration with Nike, it has technology and all kinds of data related to running that Undercover could never develop by itself. It is the same for the collaboration with Uniqlo, especially for children’s clothing. If Undercover made childrenswear by itself, it would cost as much as adults’ clothing. But the kids’ wear I designed with Uniqlo is offered at one tenth of the price that Undercover could manufacture it for. I have children and I know they grow fast, so I can say that good kids’ wear has to better designed and at an accessible price. Collaborations have meant that I have made things I could never have achieved by myself.

Kim: In Japan, there is a support for each other and a lot of exciting things come out of that.

Jun: Yes, we are all friends.

Kim: I’ve always wanted to do something with you, Jun; it’s on my wish list. Maybe we can do something now! I wanted to do some specifically Japanese stuff, but all in good time. It is really nice to work with people you admire so much and see someone else’s perspective. You learn things without even realizing it sometimes and I think that is a really nice way to do it. Whether you are a photographer, stylist, even hair and make-up, it makes things look completely different. I hate it when people go on about my show, when really is should be our show. There are so many people working on it and I think it is really important. Especially for young people to see that there are a lot of people behind these big things. There are so many roles involved, you can be all these different things…

‘Rebellious clothes are born out of rebellious music.’

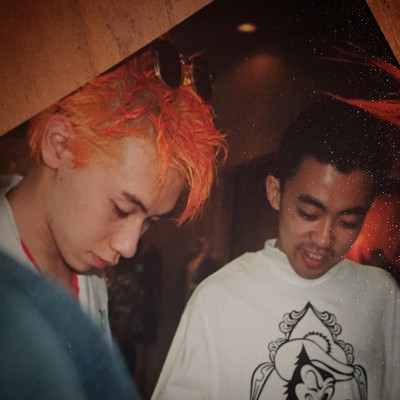

Jun Takahashi and Nobu Kitamura in conversation, April 6, 2018.

Moderated by Hiroshi Kagiyama

Nobuhiko ‘Nobu’ Kitamura is the designer behind Hysteric Glamour, the pioneering Japanese streetwear label he founded in 1984, and a long-time friend, mentor, spiritual older brother and drinking partner of Jun Takahashi aka Jonio-san. System sat the pair down in Tokyo, to discuss the past, present and future of streetwear and how the world has finally caught up with their vision.

It’s a bit abrupt, but how about starting with your past, or stories of old days? First, I would like to ask Joniosan: how did Nobu-san help you start your career? How did he influence you?

Jun Takahashi: When I was in the first or second year of high school, I went to Ashikaga, the town next to mine.

Nobu Kitamura: My first ever Hysteric Glamour store was in Ashikaga. I often went to Ashikaga and Takasaki to visit the stores that bought our products and attend events. In 1988, the person who

set up stores in northern Kanto said we should have a party there. So I went up to Takasaki, near Jonio’s hometown, and we had a Hysteric Glamour party where I DJed. And he was there.

Jun: I went to the party with my friends from my hometown.

Nobu: Much later, I happened to bump into a friend who I hadn’t seen for decades. He showed me a photo from the party, then said: ‘Nobu-san, isn’t this photo nostalgic? You were the DJ.’ I replied, ‘Yeah, good old days’. Then I looked at it again and saw a Hysteric Glamour ‘Spider-man’ T-shirt and when I enlarged the photo, it was Jonio wearing it!

You were already wearing Hysteric clothes at that time.

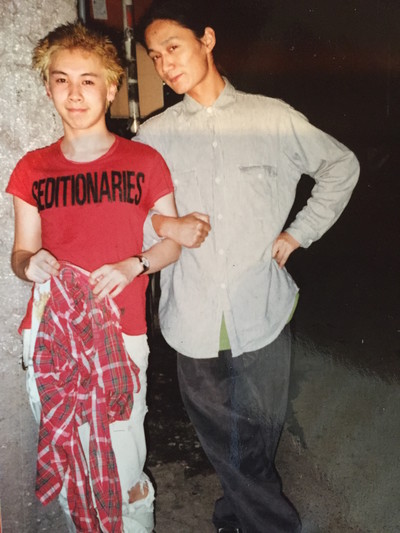

Jun: I went to the store in the next-door town almost every week by train to find out about Hysteric Glamour; I loved the clothes there. At the time, DC brands like Comme des Garçons, Melrose or Grass were the trend. Only DC styles – the so-called mode – were available then. But Hysteric was the first brand from Tokyo that integrated fashion with music. It incorporated pop culture and everything. It amazed me. I started visiting the store and bought clothes. That was the start of everything – my encounter with Hysteric Glamour. I went to the party with my friends as a customer of Hysteric Glamour, and went wild. I later went to Tokyo to enter Bunka Fashion College and launched Undercover in 1990. Then, the following year, I went to London and became friends with Michael Kopelman from Gimme Five and his peers. It was around then I actually got to know Nobu-san in Tokyo.

Undercover emerged from that time?

Jun: Yes.

Nobu: I started Hysteric Glamour when I was 21. I didn’t know how to run a business at all. The delivery service was not as developed in 1984 as it is today, so after work, I would drive to the Kiryu area where fabrics were produced and sewing and embroidery factories were located. It was a traditional area for apparel production. At night, I would take patterns to embroidery factories and then receive the finished embroidery. The place I visited happened to be close to Jonio’s hometown.

Jun: Very near.

Nobu: Looking back, it was amazing that I went up there so often. It was a coincidence. After that, we had another coincidence with London and all the people here today; Michael Kopelman was part of that. We met the same people through him and we had many friends in common, but we never saw them at the same time. We finally met after this series of coincidences and discovered that our shared love of music and movies meant we could have great conversations. I found Jonio very knowledgeable about things I was not interested in at all and Jonio didn’t know about the things I was interested in. So we taught each other. It was amazing. We are not simply friends, nor is it a kind of junior-senior relationship dynamic. We work independently, but occasionally, we get together and it feels totally natural. How can I define our relationship?

Jun: Very mysterious.

Nobu: Yes, almost like brothers.

Jun: When I was in high school, I used to love visiting that Hysteric Glamour store so much. And after meeting with Michael, Hiroshi and many other people from that scene, I met Nobu-san and

learned a lot from him. He influenced my work. Even with our families, we are like brothers.

Nobu: Like relatives. I was born in Tokyo, but I feel the area where Jonio was brought up is my second hometown because it was the company in Ashikaga that agreed to run a store for me after

only looking at my drawings and ideas, instead of the samples I was supposed to make. It was very strange. Coincidences followed one after another, and things seemed meant to be, and then

just became obvious. A friendship generally requires constant communication, but we don’t need it much because we are like relatives or brothers.

Jun: It’s really amazing.

‘I found Jonio very knowledgeable about things I was not interested in and Jonio didn’t know about the things I was interested in. We taught each other.’

Both of you are leading experts in twisting overseas culture and music, and incorporating them and expressing them in your designs and brands. Jonio-san, you said you were greatly influenced by Nobu-san. How exactly do those influences reveal themselves in your own clothing?

Jun: Neither Nobu-san nor I make clothes out of nothing. Both of us create clothes using whatever has influenced us, whether that’s music, movies, culture or something we just think is cool.

Neither of us simply makes clothes – and there aren’t many designers like that. But the kind of clothing we make is now being acclaimed – finally. Designers like Kim Jones, who are working for big brands, are drawing attention towards us. Street fashion has become more influential and finally reached the level of ‘high fashion’. But both Nobusan and I have designed like this from the start. For me, it’s never been about just designing clothes.

Nobu: I realized I wanted to be a designer in my teens and started my brand in my early 20s. My career will have lasted 35 years next year. I am getting older and I have witnessed a number of changes in fashion, but I have managed to survive. But thinking of Jonio’s ‘finally’, I feel that the time has finally come when I can enjoy things again, including the city of Tokyo, from zero – now, finally.

It may be rude to put it this way, but what the top-class, foreign, prestigious brands are doing now is what we have been doing since the beginning; they have finally started doing the same thing as us. We have been creating street fashion for a long time and now, traditional companies, leading companies, and world-renowned high-fashion brands are using the same ideas. Things are becoming interesting again. ‘Finally!’ as Jonio said. Here in Japan, if we think about who has been essential in Japanese fashion, then what Jonio has done at Undercover is significant. Without Undercover, fashion in Tokyo would not have won the respect it has now, especially from European designers.

We already had [Rei] Kawakubo-san, but we had only her. Jonio’s entry into the overseas market greatly increased the level of knowledge about Tokyo and its subcultures. Younger designers in

Belgium and New York emulated and followed him. From the beginning, I’ve never wanted to grow my business into something big; I’ve wanted to stay in a grey zone where I can design for many years as part of a small team. Jonio has continued to present his collections on the prestigious stages, though, and sport brands have also approached him. We are in totally different places. Jonio has risen to the top in Tokyo and I think this stimulates young people the most.

Jun: I take a different approach from Nobu-san. I discovered Hysteric Glamour right after I first encountered Comme des Garçons. Both of them shocked me in the same way. So did Vivienne Westwood. She had already been making culture with Malcolm McLaren; mixing music, fashion, and

so on. Nobu was doing the same. While being inspired by those brands, I was also looking at haute couture; I wanted to mix all those different elements that inspired me. And Paris was the place that made me think about how and where I could present such designs. I think Raf Simons is the same as me; he is also turning a culture into clothes. There are only a few designers around doing such things. Now, of course, Virgil [Abloh] has been appointed as men’s creative director for Louis Vuitton. He

is still not mature enough as a designer, but he can create big movements through his communication – and it’s very telling that such a person can today work for Louis Vuitton. There are both arguments for and against, but now is such a different era from the past. Some people consider popularity to be more important. Those kids like Virgil who have been influenced by us are at the

centre of things now. I do think they still need to work harder, but if they do their best, it’ll be great. We were the same back then. Anyway, people like Nobu, Raf, Vivienne and me who mix music, movies and art into our creations are peculiar in this industry.

‘Neither Nobu-san nor I make clothes from nothing. We create by using the things that influence us: music, movies, things we just think are cool.’

I have a quick question about ‘streetwear’, the word. When you first started, people didn’t call this style of clothing streetwear and I find it such a strange expression. I mean, when did people even start saying streetwear?

Nobu: In the 1990s, Stüssy and Supreme emerged and raised the profile of socalled ‘sidewalk culture’, which was represented by skateboards and graffiti, and came in from America. It may not have originated there, but it was popularized in America. The music I was listening to was different, but I was in the same generation as that culture. It led to Urahara culture. Before that, the DC style prevailed. All that happened so that street culture could appear in Japan. Then young people embraced that culture.

Jun: Like Stüssy and Supreme, I make clothes out of the things I was influenced by, such as music. Rebellious clothes are born out of rebellious music. When I started showing in Paris, journalists called us a ‘street brand from Tokyo’; even now I am introduced as a street brand. But to me, street and mode are the same.

Nobu: Street or punk, everything is good. Music, a book you read, a design, all of that can change your fashion. So it’s simple – with what concept do you make clothes? There are conventional ways to design, but if you stick to them, like learning only from old fashion magazines, all you do is change the shape of Dior clothing or American military clothes. If you incorporate different things, such as the music you hear, that will result in a change. There is a way of thinking at a higher level like Kawakubo-san, but it is also OK to apply that idea to casual clothes.

You two incorporated that new idea and your cultural inspirations, and expressed it all earlier than anyone else.

Jun: Nobu-san was the first person who did that. Other designers may have had musical influences, but Nobu was the one who concretely made clothes incorporating cultural elements.

Nobu: It is not difficult. When I started studying clothes at vocational school, military fashion was the trend in the Paris collections, and women were wearing jodhpurs and knee-high boots. My design already included street elements, and vintage clothing, so I was like, ‘Why don’t we take a men’s MA-1, and then make it very short and very tight for women?’ I started this way, so in this sense, it could be said I was the first. But the next year I saw similar clothing at Gaultier, worn by Madonna. I may have been the first to do it, but it spread and it’s nothing special now.

Jun: Streetwear has now taken root and no one can deny its influence. That kid who was listening to all those types of music back then made some clothes and he has finally been recognized by high fashion brands.

Nobu: This movement must have already been seen in the 1960s and 1970s, but fashion was then created under separate anti-government, religious, anti-racist or women’s liberation influences. But in the current era, everything has merged. People listen to hip-hop, rock, folk, popular songs.

Things have finally reached this borderless level.

Jun: Basically, I have created and shown clothes in the spirit of ‘anything goes’ – there is no high or low culture or design anymore. At the beginning, I was criticized for that. But now, mainstream fashion is also about ‘anything goes’. My generation was raised in a more mixed culture than Nobu-san’s. Hip-hop appeared and was mixed with rock, hardcore and more. And now we can no longer even tell what’s in the mix, what genre anything is. Mixing started in my lifetime. I was lucky because I

understand the process of mixed things together. My encounter with the London crew was meant to happen, and it was important. There was Hiroshi and Nobu-san…

Nobu: …and James [Lebon], Mark [Lebon], and the Buffalo Collective. Not forgetting [Christopher] Nemeth, Judy Blame, Shawn [Stüssy], and others.

These pioneers led to street fashion in Japan.

Nobu: Honestly, if our peers in Tokyo

had not communicated with Michael

and other people in London during the

second half of the 1980s and the early

1990s, we would not have come so far.

The momentum at that time was a fashion revolution.

Jun: I agree.

Nobu: It was like the Meiji Restoration.

Jun: If we had not established the strong relationship with them, street fashion would not have expanded as it has now. Stüssy is a good example; it spread worldwide from the London team and

Hiroshi.

Nobu: That is why this is categorized as street fashion – the reason lies in London. Street fashion is unthinkable in LA, because everyone drives; nobody walks on the street in LA. It could not be in New York, either, because the city consists of blocks rather than streets. So, we have London. This street, that street – and fashion is different on each street. Street fashion derived from there. I thought skateboards made street fashion, but I was wrong. London is where street fashion originated.

Jun: Music and culture linked up to make street fashion. Skateboard culture is a bit different. London is especially linked to the street, when you consider things like the Mods on Carnaby Street.

London was really influential.

Jun: In the 1970s and 1980s, Tokyo and London were more underground

Nobu: In the 1960s and 1970s, Tokyo was kind of like a third city. It wasn’t a main world city; everybody just followed the trends that came from America and Europe.

Jun: We were following, but we still created some original underground music and culture.

Nobu: Japan is an unusual country. It’s the same size as California and the equivalent of half the US population lives here. It’s really different from American or European or even other Asian countries. Japan is just an island, a little island the same size as California.

And because it’s an island, it’s a different culture. I have a question about the word Urahara. Did anybody ever use it or was it just journalists?

Jun: Urahara is basically around here.

Nobu: It’s behind Omotesando and the fashion area, which was kind of expensive, and rent used to be cheap around this area. So for young people, it was easier to rent places. The main part of

Harajuku is from Harajuku Station to Meiji Street and then here is Omotesando, right? And Urahara is the area kind of behind or ura.

Jun: Nigo and I opened the Nowhere store down there.

How is Japanese street culture evolving? How do you two feel about Tokyo or Japan’s present street culture?

Jun: Street fashion includes everything, so I cannot tell who does what and what is ‘street’ any more. All the brands are unknown to me. Later today, we are going to have some drinks and many

young people will come. So I’ll be able to witness what that current mixture is about in Tokyo.

Nobu: If I reject what’s happening now, it’s the same as people who rejected punk when punk was in fashion, or hippy culture at the time of the hippies, or the beatniks in the 1950s. We are living in a completely SNS [social networking sites] culture. It’s like how cyberpunk novels by J. G. Ballard and Neuromancer from the late-1970s to the mid-1980s became the sources of inspiration for the people who helped make Apple and AI appear – it cannot be helped. Without punks, for example,

we would not see people with tattoos working in banks.

Both of you sell your brands’ products at home and abroad. In terms of both domestic and global fashion, what is it like working as a Japanese designer?

Jun: I’ve made designs that only a Japanese person could create, by, for example, mixing up cultures. At first, I wasn’t conscious of creating specifically Japanese designs, but after I started working overseas, people pointed it out and made me aware of it. As I often mix cultures, I now know what is more of a Japanese characteristic. This makes me confident.

Nobu: No matter what other people out there are thinking, my final goal is to make clothing in Japan. I have no intention of making Japanese clothing in a foreign country. It could be possible. I

could make them in China and sell them worldwide. That may be a business plan. But my opinion is that Japan is a very small country with many fine small factories. While I can still work with them, I don’t want to eliminate that possibility. Clothes may be expensive, but these people have to make a living, too, so as long as I can get by, it’s all good.

All the stories you’ve talked about so far are now connected: Hysteric influenced Jonio-san, and led to Urahara, while people from England connected everyone here.

Jun: Until recently there were not strong links between people in the fashion industry, but we have all started to link up in recent years.

Nobu: I think we have finally entered the next stage of time in a sense.

Jun: What we have been working on has finally been appreciated worldwide, or has started to exert influence.

Nobu: Fashion lovers in their teens and 20s are wealthier than in the past. Undercover’s influence on these highly fashion-conscious people is significant. Jonio’s label shows in Paris, which increases its global presence, and he really maintains that position. I can name only Jonio, after Kawakubo-san,

who has achieved that.

‘We already had Rei Kawakubo-san, but Jonio’s entry into the overseas market greatly increased the level of knowledge about Tokyo and its subcultures.’

You’ve been sharing and interacting for 25 years now. Is this sense of collaboration a mark of your generation of designers?

Jun: Designers in Tokyo like me, Nobusan, [Takahiro] Miyashita, and others all get along really well. We are always exchanging information. We are on good terms. Collaboration is nothing special for us. We get along well, so we say, ‘Let’s create something together’. Overseas, it seems inconceivable that designers could get on so well; they’re often like enemies. Japanese designers,

at least those around me, are not like that at all. This idea of working together has finally started spreading in the fashion world outside of Japan. This may be thanks to Kim and other designers working for big brands collaborating with brands like Supreme, for example.

You share and resonate with each other, while being rivals at the same time.

Jun: We have no sense of rivalry.

Nobu: Confrontation is of no benefit. A long time ago, people were in conflict with each other over territory, but now, countries have been established. If we’re in conflict with each other today,

all we’ll get out of it is stress. But if we get along, it is better to help each other. We are living on a small island, so we have to do this.

Jun: Actually, we do have a punch up once a month. [All laugh] When we go drinking once in a while…

What do you like or dislike about Tokyo?

Nobu: I like Tokyo very much, and I am learning to like it more and more. To be honest, when I was around 20, I felt an aversion to Tokyo. I used to think, ‘Why wasn’t I born in London or New York?’

I didn’t even like the people who had come to Tokyo from the rest of Japan. When I was in my 20s, I just didn’t like them. But because I started my brand, I couldn’t live anywhere else, and now I’m less interested in other cities…

Jun: There is nothing that I dislike about Tokyo. I liked it from the beginning. I sometimes think I’d like to live in London, but…

Nobu: Even if I am alone here, I can do everything. If I were alone in London, I would commit suicide. I can’t find anything I dislike about Tokyo. Maybe electricity poles and pylons. If they were

removed, it would be much better.

Jun: If you compare the cityscape in Paris and that in Tokyo, you may think Paris is greater. But I think Tokyo is just fine. Tokyo has first-class culture, as well as many nonsensical things and traditional stuff – everything is mixed.

Nobu: The reactors’ meltdown problem has not been fixed. I hope the groundwater will not rise.

Jun: Ahead of the Olympics, the government tries to hide the problem and pretend nothing has happened.

Nobu: There must be something that can be done. It’s a pity. There are people who were evacuated from their homes after the meltdown and still haven’t returned. We have more important

things to be doing than getting involved in the Tokyo Olympics.

Jun: After the earthquake disaster, SNS happened to spread wide. Right after that, our business plunged, and I was hit hard. The government manipulated information behind the scenes to distract us from the problem, while emphasizing the Olympics. People say business will change after the Olympics, but that’s not right. Because if another nuclear power plant explodes, that would be the end.

We Are Infinite & Order-Disorder

Deciphering Jun Takahashi’s Autumn/Winter 2018 Undercover season.

By Tim Blanks

Photographs by Norbert Schoerner

Styling by Jun Takahashi

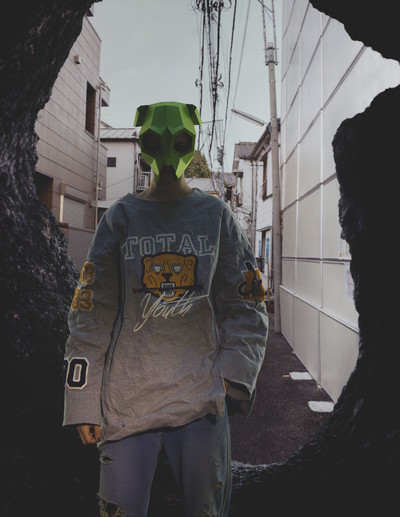

On March 2, 2018, Jun Takahashi showed We Are Infinite, his womenswear collection for Autumn/Winter 2018. His title, which he took from the closing monologue of the film, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, was a perfect summation of Takahashi’s theme, the light and shadow of tumultuous teenage years, and a continuation of his long-term obsession with extremes. The soundtrack, selected as ever by the designer himself, was the consummate aural complement, ranging from the sweet-16 of Paul Anka’s ‘Put Your Head on My Shoulder’ to one of Julee Cruise’s eerie hymns to David Lynch’s twisted vision of adolescence.

The high-school culture of We Are Infinite also reflected the fascination with Americana that Takahashi shares with Japanese culture. Jazz, blue jeans, gas jockeys, bobby-soxers, rockers, preppies: handfuls of archetypes are regularly curated, mutated, filtered through the alien lens of Japanese fashion. If adolescent rites of passage initiated one of Jun’s more fetishistic reflections on the heartland, there was no denying the genuine emotional charge of the finale, when all his models walked in collegiate parkas to Bowie’s ‘“Heroes”’, echoing the most uplifting sequence in Perks. Later, Takahashi told me it was the bittersweetness of such a time in a young person’s life that attracted him, the uncertain face-off between the present and the future. But while he was designing his collection, he had no real idea how much more bitter the real world was about to get.

Two weeks before Takahashi’s presentation, 19-year-old Nikolas Cruz walked into Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida with an AR-15 semi-automatic assault rifle and murdered 14 students and 3 staff members. Unappeased by the thoughts and prayers of ethically compromised, morally bankrupt politicians, the kids who were the targets mobilized in anger, making plans for a nationwide march for their lives to challenge the orthodoxies of America’s out-of-control gun culture.

Of course, Takahashi’s concept had been in place months before, but the coincidence darkened the shadows of We Are Infinite. His meditation on high school concluded with an allblack passage of formal sportswear – a shawl-collared parka, a frock coat – that post-Parkland, made me think of funerals or proms that would never be attended. Though it wasn’t all darkness. I saw the ‘“Heroes”’ of his finale as the resilient young survivors taking a stand for sanity. More words from the Perks monologue: ‘This one moment when you know that you’re not a sad story. You are alive.’ Which was also the moment that those kids realized monsters are real.

Maybe Takahashi was taken aback when I told him all this. Unsurprisingly, he insisted there was no way it would be possible to address such a tragedy with a collection of clothing. That still didn’t shake my conviction that there aren’t many other fashion designers today whose work could carry such a weight, however unwittingly. Over the years, his clothes have been fearlessly conceptual, sometimes wilfully so. It’s long been Takahashi’s method to probe the hidden, wayward – even perverse – recesses of the mind. When he was a child, his parents would lock him in the coal shed when he misbehaved. The darkness of that small, spooky place nibbles at the edges of his psyche.

‘Since I was little, “fun” and “beautiful” weren’t enough. If comedians were just funny, they didn’t fascinate me. They were more interesting if they had the other side too, if they

were cynical as well. I tried to find out what was behind.’ You can’t miss how often masks crop up in his collections. (His Spring 2018 collection was titled Janus: The Two-Faced God.) He has called himself ‘normal on the outside, alien on the inside’. Which explains why he labelled his business Undercover – anonymous, secretive, hinting at taboo – when he started it in 1990.

Takahashi also claims he likes being frightened; he says he has a lot of nightmares. They seep into his collections, through the music and the lighting. He intentionally avoided

a dark side with We Are Infinite, but when he saw the finished collection he realized he hadn’t escaped the darkness: ‘Youth was the story of the show, and there is always pain, always difficulties with that story.’

If The Perks of Being a Wallflower was one take on troubled adolescence, Takahashi drew on another, when he cast Sadie Sink, the young actress from Series 2 of Stranger

Things, one of his recent favourites, to open and close the show. Their connection was actually a little more prosaic than it at first seemed. Long-time Takahashi collaborator Nike was using Sink in a campaign and the company brought her to the designer’s attention. We Are Infinite was almost complete at that point, though Nike had no idea what Takahashi’s concept was. They were thinking maybe a shoot. He instantly shot back: ‘No, I want to make her the main character in the show.’ It was a multilayered moment. Maybe even meta.

Takahashi has called himself ‘normal on the outside, alien on the inside’. Which explains the name Undercover – anonymous, secretive, hinting at taboo.

Over and over again, I’m thinking of David Lynch, and his unerring ability to isolate the unsettling in the familiar. On one finger, Takahashi wears a ruby-eyed fox-head ring by

Gucci, a gift from his wife. On another, he has a ring with the symbol of the Black Lodge, from Twin Peaks. He’s halfway through the latest season of Lynch’s series and when I inadvertently launch into spoilers (though that is virtually impossible with Twin Peaks), he says, quickly, ‘Don’t tell me’. He considers Lynch a genius, ‘next level’. There’s a clear compatibility. ‘I like to make people nervous,’ he agrees. ‘I hope to make people feel that through my show.’ He acknowledges it’s a challenge to scare people with fashion, but he felt We Are Infinite had something unsettling about it, ‘when you don’t know what’s going to happen next’. How Lynchian is that!

Those words could be inscribed on Takahashi’s tomb. Which is why there’s one question in particular I’ve always wanted to ask him. How does he choose his subject matter?

Surrealist Czech filmmaker Jan Švankmajer. Jazz pianist Bill Evans. Collagist Matthieu Bourel. He’s curator as whirling dervish. Relatively familiar, but still arcane, names like

Trent Reznor or Lou Reed emerge from the reference points like old friends. Undercover is entirely a reflection of Takahashi’s own tastes. He designs everything by himself, graphics included. He writes all the text that decorates his clothes. (On We Are Infinite’s parkas: ‘We are who we are for a lot of reasons.’) No assistants, no stylist, no musical director. ‘I enjoy what I create. I take care of every part of my creation.’

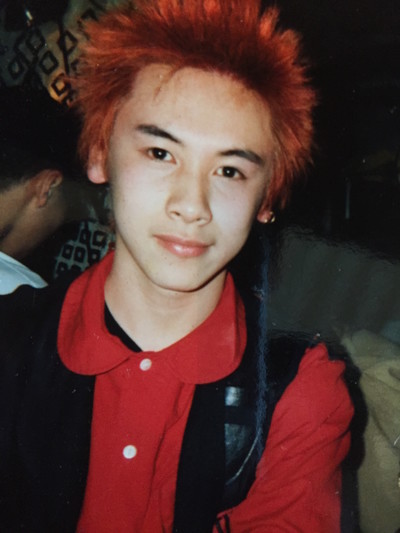

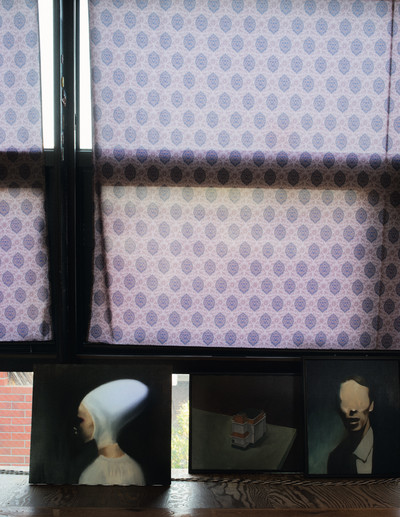

Three seasons later, he did something similar with the Belgian artist Michaël Borremans, the arcana this time less related to the inspiration’s obscurity than its unlikeliness in a fashion setting. Borremans’ sombre, eerie portraits have cast him as a 21st-century Velasquez and when Takahashi encountered his work in an exhibition, he instantly felt a kinship: ‘Everything for me is thinking about fashion and design and I was already thinking about how I could get these images into my clothes.’ Borremans consented; Takahashi reproduced a handful of images on parkas, coats and sweatshirts, to the unmitigated joy of Borremans aficionados everywhere who can’t afford the seven-figure price tags and who could relate to Takahashi’s own sentiment: ‘If I find something I really love and make clothes with it, I can have it with me all the time. It makes me happy to have it very close, very personal to me.’ Not everyone says yes to him. It would be betraying a confidence to mention a very big fish who got away. I could shed a tear at how inevitably wonderful the result would have been. At the end of the 1980s, Takahashi emerged from a cocoon of punk into life in Tokyo as Jonio, the rooster-haired front man of the Tokyo Sex Pistols. He’s now in his late 40s, slight with a studious look that might have something to do with hair that is slightly greyed. Maybe he’s done that deliberately,

to look a little older, to counter an innate boyishness. We’re conducting our conversation with the assistance of his righthand woman and translator Chieri Hazu, but every so often Takahashi injects his own Anglicisms. As, for instance, when I’m cackhandedly trying to explain Rei Kawakubo’s recent proselytization on behalf of the contrary and vital value of camp and her conviction that ‘so-called styles such as punk have lost their original rebel spirit’. ‘Why do you think she said that?’ Takahashi wonders. I suggest it might be because punk got old. ‘It doesn’t get old or new,’ he counters. ‘What I got from it is always there. It was shocking for me at the time, and it never changes.’ He looks at me, raises an eyebrow, and murmurs, in English, ‘Punk’s not dead.’

He designs everything by himself – graphics included – and writes all the text that decorates his clothes. No assistants, no stylist, no musical director.

Jonio is no more. Now Jun only sings when he’s doing karaoke with his friends. Last time, he chose ‘“Heroes”’; he laughs when he remembers how bad it was. ‘To listen to it

is amazing, to sing it so difficult and boring. David’s voice makes that song so moving. I realized again how great he was.’ Maybe there’s something of the kindred spirit, like Lynch, again. What sustains and excites Takahashi more than anything continues to be his creative process. ‘Sounds boring,’ he says in English. Not at all. It sounds impressively disciplined. He comes to the office every day at 11, leaves at 7, doesn’t bring his work home with him and takes weekends off. Obsessive? ‘I like to be scheduled,’ Takahashi says. ‘Without plans, I get lost.’ His early training in graphic design has made him a stickler for detail, but he insists that he’s not obsessed with precision. (‘It’s not like everything has to be straight.’) Which means there is also a roughness in his work, an unfinished quality, cracks in the perfection into which dark shadows and wayward sensuality can creep.

Perhaps that’s the perseverance of punk in Takahashi’s career, as raw attitude. Nowhere was the name he chose for the store he opened in 1993. ‘We make noise, not clothes’ has long been the company slogan, even if that particular message was eventually muted by the elaborate, highly stylized bordering-on-rococo spectacles Takahashi staged for his womenswear. That is all about to change. We Are Infinite was Takahashi’s last womenswear presentation for the foreseeable future. From June, his menswear will take its turn on the catwalk, with the strong likelihood that Takahashi will let the punk rule the poet.

He’s long thought that it was more challenging to make a men’s show interesting: ‘Womenswear is not something I would wear myself, so I’m thinking of a story, and the characters in that story.’ Cinematic, in fact, like the movies he wishes he had time to make. Only in the last few years has Takahashi found the confidence to put his menswear centre stage, as it were. He claims he was intimidated by all the rules. ‘Things have to be this way or that way, and I don’t like that,’ he explains. ‘But I didn’t know how to break the preconception, how to find a balance between breaking the rules and also following them. I’ve finally figured out how.’ Takahashi now wants to parade his solution on a runway, even as he cryptically adds that he’s still not sure if there’ll be a story as there has been with the women’s shows.

Which mean that his confidence must have been received an added boost in January this year with a show at the Pitti Uomo trade fair in Florence. Takahashi and his friend Takahiro Miyashita, who designs as TAKAHIROMIYASHITATheSoloist., were invited as special guests. ‘We had the theme already: Order-Disorder. It’s really the story of now, how we created the computer, and artificial intelligence is taking over. We made it; we have to deal with it.’

For his half of the show, Takahashi took 2001: A Space Odyssey as a starting point. (Stanley Kubrick is another of his pillars.) The alien monolith from the movie loomed at the

end of the catwalk while his models walked in sportswear embellished with film stills and words that mirrored the plot: HUMAN ERROR, COMPUTER MALFUNCTION, and the name of the iconic AI gone wrong, HAL 9000. Takahashi’s soundtrack, always a signifier, included Joy Division’s ‘Atmosphere’ and Kraftwerk’s ‘Radioactivity’. There was a dystopian edge to the presentation, but it also offered ceremonial evidence that Takahashi is just as capable of offering a narrative in the context of a menswear show as he was with womenswear. In fact, his evocation of the ambiguous relationship between human and machine struck me as a companion piece with the sublime women’s show he staged for Autumn/Winter 2017.

The full title of that one was But Beautiful III Utopie: A New Race Living in Utopia. To a Thom Yorke soundtrack, Takahashi unveiled a vision of a society of 10 separate, ornately dressed tribes, among them ‘Aristocracy’, ‘Young Rebels’, ‘Agitators’, ‘Soldiers’, and ‘Monarchy’. If the set-up sounded hierarchical and unstable, Takahashi actually intended to

depict a world where all classes were equal, a utopia where the idea of class had been destroyed. ‘AI doesn’t care what class you are,’ he said. ‘It’s a different level of new experience. But how we are going to face it is another matter.’ Humanity united in a face-off with AI? Was this Takahashi’s idea of optimism? ‘Not completely,’ he answered, ‘considering what’s happening in the world. It’s a warning of what’s happening. I have two kids. We have to survive some way, but it’s so difficult to avoid all problems.’

‘If I find something I love and make clothes with it, I can have it with me all the time. It makes me happy to have it very close, very personal to me.’

In ‘New Species’, the last of his Utopie’s 10 tribes, Takahashi offered an update on an idea integral to his work all along. ‘I like to make hybrids. For my “new species”, I combined humans and bugs. In reality, it would be a horror movie.’ Or maybe, ultimately, a guarantee of survival. A real new race, living in a utopia that we would scarcely be able to recognize as such. I was recently overwhelmed by Alex Garland’s Annihilation, and it’s only now that it strikes me how much its intimidating, alien beauty is the kind of elaborate hybrid fantasia about which Takahashi has dreams – or nightmares.

‘It’s possible to do more in fashion than people do,’ he insists. ‘Fashion can be the reason for a person to change, maybe even the reason to change some part of society. It

depends on the person. It changed everything for me.’ One of his most appealing qualities is the sense of reflection Takahashi exudes, like someone who has led a rackety life and come to this quiet place. (I was going to compare him to Iggy Pop, but Pop seems a little more amused by everything.) He thinks about legacy, for instance: ‘It’s valuable to leave something. I always wanted to combine street and high fashion. I wanted to show people there is a way to do things like me. And I can leave a mark by showing in Paris’ – which he has been doing since Rei Kawakubo persuaded him to make the move in 2002 – ‘it’s more than just designing clothes. I’m showing a world, and if you can name it, it becomes one style, your style. That’s my dream.’

I felt that too in Martin Margiela,’ Takahashi adds. It was a Margiela show in Tokyo in the late 1980s that originally awakened him to the potential of fashion. Since he’s been in

Paris on this visit, he’s taken in the designer’s retrospective at the Musée Galliera: ‘The power, the energy of those clothes. I want to do that for myself. It’s difficult to find something that gives you that.’ Takahashi is thinking ahead to his men’s show in June. The little monsters in Alessandro Michele’s most recent Gucci show have set him wondering. ‘The baby dragon was such quality,’ he murmurs dreamily. ‘If I had that kind of money, maybe…’

With the change he is making, it’s clear that Takahashi wants to address a core frustration he has with his business. ‘People in the West have a very different idea of Undercover

than people in Japan,’ he acknowledges. ‘European journalists understand me in the way I want to be understood.’ Meaning in Japan he is forever the street designer who launched Nowhere with Nigo, he of A Bathing Ape, and helped make the Harajuku district what it is today. ‘That’s the kind of image I have with people who are now in their 30s or 40s, even professional journalists, even those crazy fans of Undercover from back in the 1990s. They’re, like, religious. They don’t get it when I do something new.’

Takahashi loves collaborations. He excels at them: Supreme, Nike, Uniqlo. But they have also consolidated the preconception. Last year he broke the mould by linking up