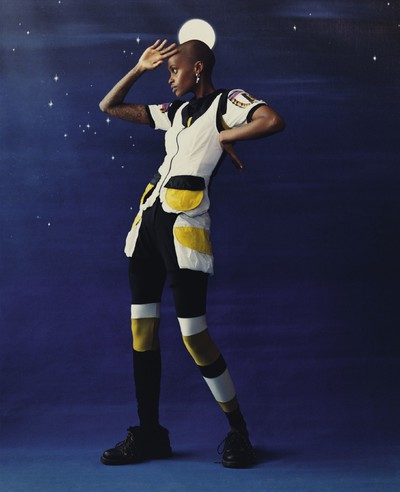

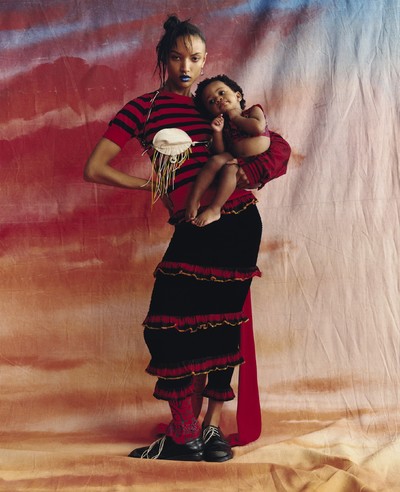

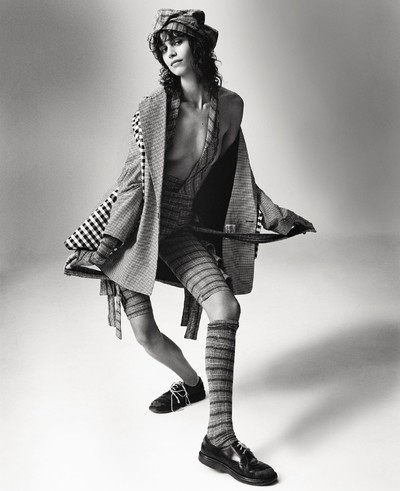

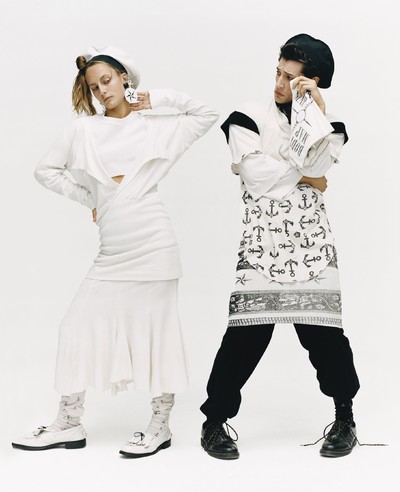

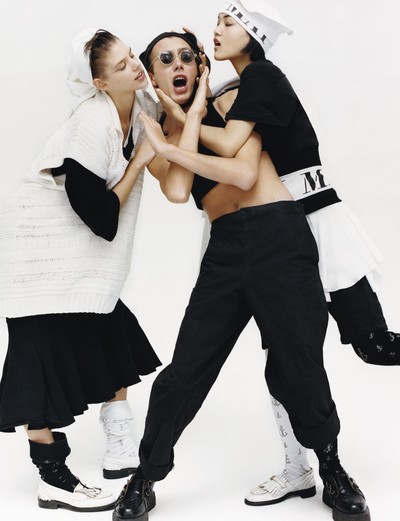

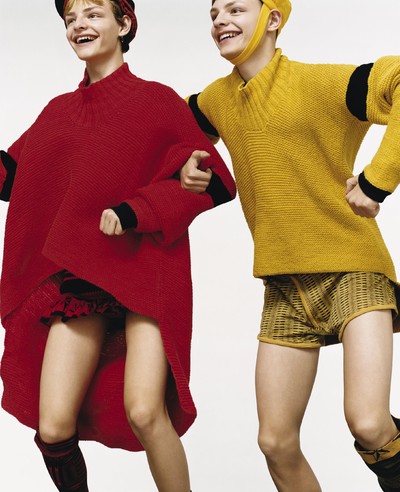

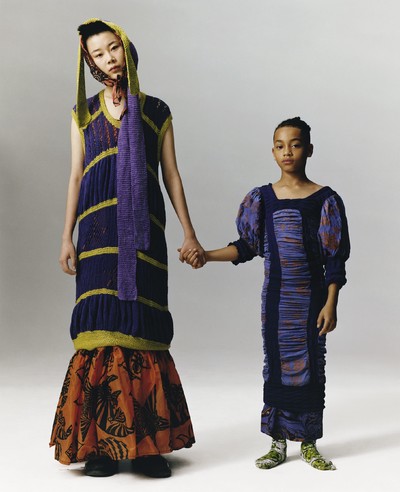

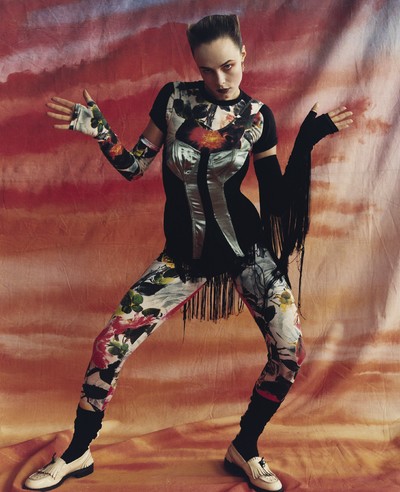

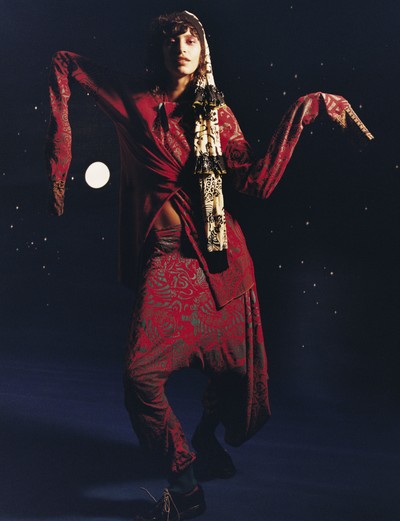

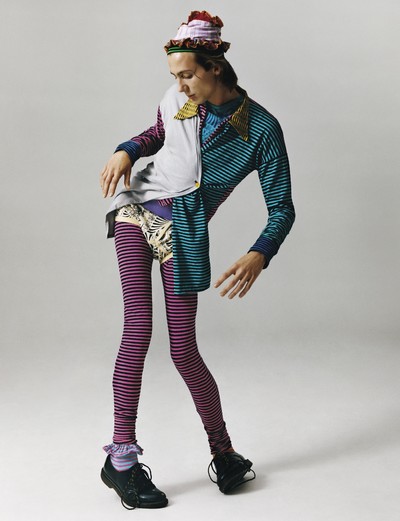

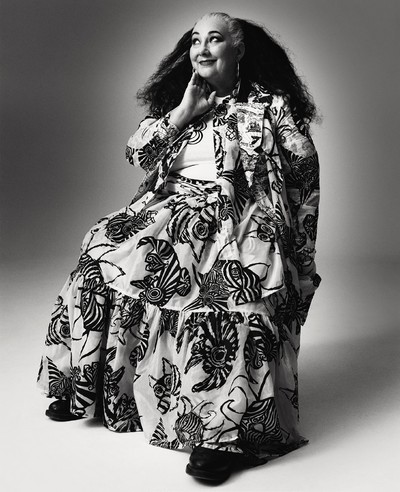

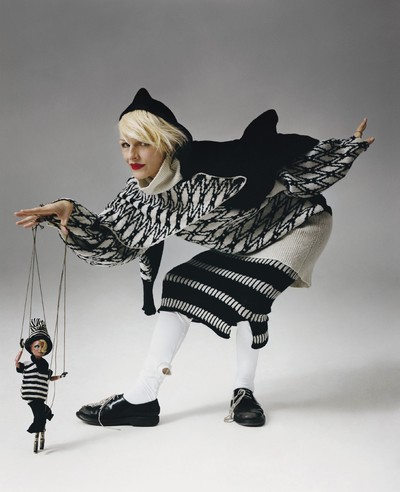

Stevie Stewart and David Holah’s 10-year BodyMap adventure is an unlikely story of 1980s London, style as performance, hedonistic times, the inevitable comedown, and a fashion legacy that’s never felt so modern.

By Tim Blanks

Photographs by Oliver Hadlee Pearch

Styling by Vanessa Reid

Navigation: Russell Marsh.

Director of photography: Errol Rainey.

Photographer’s assistants: Jack Day, Mitchell Stafford, Bella Sporle.

Stylist’s assistants: Ewa Kluczenko, Kyanisha Morgan, Hannah Ryan.

Hair stylist: Cyndia Harvey.

Hair assistants: Blake Henderson, Reve Ryu, Shanice Noel.

Makeup artist: Thomas de Kluyver using Maximalisme de Chanel and Chanel Sublimage Strengthening Essence.

Makeup assistants: Thomasin Waite, Carly Lim, Anastasia Hess.

Set designer: Alice Kirkpatrick.

Movement director: Les Child.

Casting director: Adam Hindle.

On-set production: James Ward.

Personal archive kindly provided by Stevie Stewart and David Holah of BodyMap.

Shot at Spring Studios, London.

Talent: Mica Argañaraz at Viva, Luka Badnjar at Wilhelmina, Martina Boaretto at Viva, Youn Bomi at Premier, Duke and Jo Brooks, Edie Campbell at Viva, Olympia Campbell at Viva, Scarlett Cannon, De-reece at AMCK, Joséphine de la Baume at Tess, Ethan Domaradzki at Supa, Finn at Linden Staub, Paul Hameline at Success, Pan Haowen at Elite, Misha Hart at Viva, Joshua Hillman at Storm, Hirschy Grace at The Squad, Kakua at Premier,Jo Kelley, Heather Kemesky at Viva, Veerle Klok at Elite, Jess Maybury at Elite, Robbie McKinnon at Supa, Andrew Nelson at Storm, Nella Ngingo at Paparazzi, Amy Orchard King, Tyrus Orchard King, Georgia Palmer at Storm, Nicolas Ripoll at Models 1, Isla Rose at Bonnie & Betty, Sue Tilly, Louise Toohey, Allegria Torassa, Kiki Willems at DNA, Pippa Brooks, Hen Yan at Viva, Yebeen at Elite.

Everyone knows that Katharine Hamnett was wearing her ‘58% DON’T WANT PERSHING’ T-shirt when she met Margaret Thatcher at 10 Downing Street in 1984. No one knows that BodyMap’s David Holah met the PM at a similar event sporting a fuzzy racoon hand puppet on one hand; an unfazed Thatcher shook the designer’s other hand.

The BodyMap saga is full of similarly vivid, playful, anarchic details that posterity has consigned to a cultish twilight. That’s not right. In the 1980s, the rise and fall of David Holah and Stevie Stewart defined the way the world saw British fashion: the Brightest Young Things, brought down by Big Bad Business. But if the form of the saga was a cliché, the content was anything but. More than three decades on, BodyMap still has the capacity to dazzle – and touch. That’s because, at its heart, it was a love story, so intense was the connection that Holah and Stewart shared. They still do.

Today, he’s teaching printmaking to a new generation; she has a thriving career as a costume, set and production designer. Upstairs from her flat, though, there’s a room where BodyMap lives on in a thousand scrapbooks and a thankfully thorough archive of clothing. What’s remarkable is how little of it says ‘then’, as is clear from the images that accompany this piece. Holah and Stewart anticipated the future, not just in their blend of style and sport, but in the all-embracing attitude of their presentations at which all ages, sizes, genders and inclinations were served up in a celebratory stew. They made a uniquely modern family. It endures.

The Beginning

Stevie Stewart: Do you know about our stall at Camden Market? I started doing the market when I was 15. I was one of the first people to have a stall there. I was selling feather earrings. They took off, so I was selling designs to [jewellers] Adrien Mann and doing illustrations for another accessories company. Then I started going to Middlesex Polytechnic, and I’d gone from feather earrings to hair accessories and punky badges. I sort of went from hippy to punk. And then I met David on the first day of college and he started helping me on my stall, selling things like punk badges and Stephen Rothholz jewellery. He used to do titanium metal and plastic tubing bracelets. Very 1980s. In the end we got him to do the sunglasses for our collections.

Tim Blanks: How old were you on that first day of college when you met David?

Stevie: Twenty-two, I suppose. It was 1979.

Tim: Oh, I thought students were younger.

Stevie: David and I had been outside working. I didn’t get onto the foundation course at Barnet College because it was full up, so instead of waiting and wasting another year, I went on a threeyear diploma in design course there instead. One year was like foundation, the next year was fashion and graphics and in the third year, you specialised in fashion. I got a grant. It must have been when I was 18 to 21, so I would have been 22 when I started Middlesex Polytechnic.

[David arrives in a gust of good cheer]

Tim: Hi, David, how are you? Such exuberance!

Stevie: We’re trying to work out dates. I was just saying how I met you at college. My best friend was Melissa Caplan…

David Holah: …and she was my flatmate, and she told both of us to look out for each other. We actually met each other at Southgate station on the line to Cockfosters…

Stevie: …on the first day of college. And that was it. Best friends ever since.

David: It was like we’d known each other all our lives.

Tim: Funny that you had never met before.

David: I’d been doing my foundation in Oxfordshire, I had just moved to London, and I was looking for places to live, which was how I ended up at the Warren Street squat with Kim Bowen. She was temping up in the West End, and we were in college digs, up in Turnpike Lane. She saw this huge place, so lots of us could live there, and it became a really pivotal place. There were lots of parties. The Scala down the road showed lots of avant-garde films, and there were lots of parties there, too. Divine would go there. But the house got overcrowded and Melissa invited me to come and live with her, so that’s how…

Stevie: I was living at my mum’s in Barnet, but I would go and stay in David’s room on the end of his bed.

David: Yeah, on the end, because there were already people like Lesley [Chilkes] and whoever else in there. There were quite a lot of us in just one bed. From Warren Street, we were moved into council houses because we were homeless when we got kicked out. So there were all these groups of flats.

‘Warren Street squat was huge, with the insane atmosphere that comes from 20 ultra-creative people creating looks for going out in at night.’

Lesley Chilkes: Warren Street was huge, with the insane atmosphere that comes from having 20 ultra-creative people creating looks for going out in at night, and all the shenanigans around that. That was basically all we did. I met David through my sister, who was at college with Kim [Bowen] and Lee Sheldrick, and we’re still best friends 40 years later. He was a beautiful little creature – hugely loved by everybody. Kim absolutely adored him. We’re incredibly lucky, because we created a

family then and we still are one today.

Stevie: It was a different time, wasn’t it? If you wanted to live together, the council would rehouse you in hard-to-let flats. There was that policy.

David: So we got a four-bedroom flat with Jeffrey [Hinton] and [Princess] Julia and everybody. We were all in the same block.

Tim: What did you do at Middlesex?

Stevie: Because I’d done the diploma in design, I wanted to go somewhere that was more creative and of a higher standard, like a proper course. And I’d been to Saint Martins and I didn’t like it.

Tim: David, why did you go Middlesex?

David: Because I’d wanted to go to Saint Martins and [course leader] Bobby Hillson interviewed me and I got refused. I don’t know why.

Tim: How did you look in those days?

David: Well, Quentin Crisp was my inspiration, so I had curly red hennaed hair and a hint of makeup. I was quite pretty. I had a very good portfolio. Anyway, it was all very alarming that I didn’t get in.

Tim: Had you been a punk as well?

David: I ombré-ed between punk and Quentin and soul-boy, all of them rolled in with a Bowie-esque edge. The whole gamut really.

Stevie: I had a side ponytail.

David: She used to get up at four in the morning to get ready for college. She had the whole look going on. Hairdos…

Stevie: When I started, I had my hair in a side ponytail and had some sort of big, graphic, 1980s T-shirt that was white with a knot at the side. I had some purple tracksuit trousers – like leggings, but tracksuit material – some court shoes that I’d dyed, and yellow fishnet socks.

Tim: Were other people doing this?

David: Everyone had their own thing. I was a Quentin-meets-punk kind of thing, and Stevie was a sort of space princess. A compilation of all kinds of things, a bit like BodyMap, really.

Stevie: On the stall, we were selling army surplus, dead stock, and cotton flannelette pyjamas, which were a bit Mao suit-y. We bought that business from Jenny and Joan, a couple who started the first Body Shop stall after Anita Roddick’s Brighton stall, so they had huge success. Their stall was next to me when I was selling the accessories, and they also had an army surplus stall inside the Shed, as we called it at the time. And when the Body Shop stuff started taking off, they lost interest in the army surplus and we said, ‘Ooh, we’ll have that!’ The pyjamas came in pale blue and we would take them to college and get Dave the Dyer, the dye technician, to dye them in vast numbers. We would sell loads of them. We had black, purple, fuchsia pink, turquoise, with a little stand-up collar. No frogging, just poppers.

Tim: So quite institutionalized.

Stevie: Yes. They were prison pyjamas.

Tim: And then people styled them up themselves?

Stevie: We used to style them up for them. We had these cut-out, flat, 2D mannequins which we would haul up on top of the stall every Saturday and Sunday, and we would style them… And David had started selling this thing called the ‘chemise,’ which was like a cowled shift dress with long sleeves.

David: Yeah, it sort of crumpled down, with long sleeves you pushed up. I wore it all the time. It was a college project, inspired by a Jean Cocteau film. I can’t remember the name. He had a very whimsical, very drape-y feel going on, so I made the dress with the drape. And they went like hot cakes. I’ve never known anything like it.

Stevie: Probably Gerlinde Costiff wore one, and then [store owner] Susanne Bartsch saw it…

David: …and then we all wore them. Men, women, any colour you wanted, tie-dye, dip-dye – the whole gamut. I gave [journalist] Anna Piaggi a silk organza one that we’d made for a show in London. She wore it and styled it in her own way and did this whole number on it.

Stevie: But anything we did at that time flew off the shelves. Like the rope belts that I was doing…

‘My look ombré-ed between punk and Quentin Crisp and soul-boy, all of them rolled in with a Bowie-esque edge. The whole gamut really.’

David: We were just selling stuff. It was just a stall. It was our extra cash on top of our grants.

Stevie: Well, I didn’t get a grant. That’s the whole reason I became entrepreneurial.

David: So she could pay her college fees.

Tim: Did you have a sense of there being something about to happen?

David: We were on the brink. From college, we were already doing stuff with my chemises and Stevie was doing her hemp-linen deconstructed jackets. I sold my chemises to Kensington Market, originally. My brother Eric had a stall there with his stuff and Stevie put her jackets there, so then we had two outlets in London. Then [collector] Louise Doktor and her husband Terry were quite influential.

Stevie: Because they bought my stuff and your stuff and Eric’s stuff. I remember saying to you: ‘David, there’s a niche in the market and we can fill it.’ That was when we started putting our designs with the pyjamas.

Tim: What niche was that? Were your individual aesthetics kind of different and compatible, or were they really similar?

David: There was nothing else like that happening in the fashion world. I suppose it all just happened because we were at the market and we knew we could sell there, because people were buying it. We had great market research. Then it started to take off with Susanne buying our stuff and selling our clothes in her shop on Thompson Street in New York.

Tim: How much of this stuff did you sell?

David: Thousands. Lesley had a full-time job cutting and making those dresses.

Tim: Were you getting press at this time?

David: i-D and 19, yeah. Just individual stuff. I don’t think The Face had started at that point. i-D was doing loads of stuff about Camden, so we were in the pictures; it was more of a fanzine at that point.

Tim: Did you both graduate when you left college?

Stevie: Got a first, darling.

David: After college they wanted us to go to either Paris or Milan to work in fashion, like at Lagerfeld, or somewhere…

Tim: Where did they want you to go, Stevie?

Stevie: Armani. We kind of did an investigation into going to one of them. We didn’t really go, though. We met some fashion people; we hung out in Milan. But before we actually left college, when we were in the second year, we did this show called In Town Tonight and everyone else had already graduated so we were the only ones still there. It was people like [designers] Stephen Linard and Stephen Jones – that big class two years above us. A whole group of up-and-comers. David did the chemise collection and I did my long coats and jackets in linen.

Tim: It was like your Armani audition.

Stevie: It was much more distressed and Japanese-y. I got Japanese guys to model it and David had his topknot.

Tim: At this point you’re still not BodyMap, so what was the ambition?

Stevie: We were wanting to fill a niche!

Mikel Rosen: I was teaching at Middlesex Polytechnic when [PR agent] Lynne Franks got together the first London fashion week at the Commonwealth Institute. David and Stevie were in their second year and they helped me. David’s degree collection was very Valentino, very grand and camp; Stevie’s was more utilitarian. They were totally different collections. We were telling David to go to Valentino, and when he came back with no work, I said to them, ‘Why don’t you work together?’ I loved the idea of that combination: something classical with something ethnic; this gay boy David and this fag hag Stevie putting things together. That’s what kept it going. If they’d only done club clothes, it would have had no depth. And I brought Hilde Smith from the textile department. Without her prints, I don’t think BodyMap would have taken off.

‘After college they wanted us to go to either Paris or Milan to work in fashion, like at Lagerfeld or Armani, or somewhere…’

The Middle

Stevie: Our first collection together was called Matelots and Milkmaids. And we sold that. Robert Forrest made an order for about £3,000 for Browns.

David: We like to skip over that bit.

Tim: Why?

Stevie: It was an experimental phase.

Tim: You mean that was the first time you tried to synthesize your individual aesthetics and it didn’t work?

Stevie: Well, it did work because Robert bought it. But in hindsight we much preferred what we did afterwards.

Robert Forrest: I loved meeting Stevie and David. BodyMap wasn’t like anything else. We take it for granted now, because people do it all the time, but it was the first time people had their friends as models, doing the hair, doing the makeup. It was young and fresh and energetic. And it was real sportswear, with interesting, inventive cuts and great prints. I thought it was right for Browns because it was different and we could give a wider audience to it. It was the same time that Norma Kamali was taking off with all the sweatshirt stuff. Then, just after I left Browns, [owner] Joan Burstein bought Galliano’s graduate collection right off the catwalk in June 1984, and Diana Ross was waiting outside the shop to buy John’s dress in the window when it opened. She must have been staying at Claridge’s.

David: I would have loved it if Diana Ross had bought BodyMap! But Joseph bought all the jumpers. I remember that we were cutting stuff, like that tartan suit and things.

Stevie: It was a collection we did for some sort of mid-season show; I think it was called Circes. We were experimenting with shapes and using this knitted dishcloth fabric. To get some shape, we started to use jersey, and we thought that looked better. So we were making toiles out of jersey for some of the stretch things and they looked really good, and we started incorporating them with sweatshirting. We wanted to buy all of our fabrics from England. Even the jersey was from Nottingham. And we had the tartan suits and hemp coats, which was a bit of an amalgamation of what we were both doing.

David: Yeah, it was sort of stretchy with a soft tailoring feel.

Stevie: Like putting our college collections together.

Tim: The fluidity of David’s chemise with your more tailored structure…

Stevie: I was more into oilskin parkas and those sorts of things, from college.

David: What we did at college wasn’t really similar. I couldn’t sew very well, so I just made things that could be slipped on. They were big and baggy and a belt made them fabulous. I was all big circles and squares, but Stevie could sew, so she could structure and make intricate things.

Stevie: I knew about pattern-cutting because of my Barnet College days, although my coats were quite simple, like long A-line coats.

David: When it came to BodyMap, it was a mix of the two. Me not knowing, I would invent a shape from something and Stevie would discipline it.

Tim: So it wasn’t like ‘you do this one and I’ll do that one’? It was actually a complete symbiosis? That is very tricky to pull off.

Stevie: We would take each other’s sketchbooks and draw over each other’s designs.

David: We could think about a look, about whether we did it this way or that way. We kept it all simple, so we could make things quickly, because it all became about how quickly we could make it. A lot of stuff didn’t have any zips or buttons, it was all just a big pull-on. Those petal skirts were just held on with a tight rib. It was a new way of dressing. It could fit a lot of people, and you didn’t have to do the sizing. You could pull a skirt on and look a million dollars, but it was just a sweatshirt skirt really. It was all about the fabric and the cut. It was sexy. It made you look good. You felt good.

Stevie: We wanted to try something with Lycra, and going round the fabric fairs and visiting agents we discovered this Swedish company that added Lycra to its knits, because it made childrenswear and socks. Weirdly, they’d got all the knitting machines that made the ribbing and the socks from Leicester. And we went on working with them to make new fabrics for us – heavier sweatshirting with cotton Lycra, more viscoselike. And that made us think we could turn this into a business. That we could conceptualize it and do it properly.

Tim: Do you remember the moment you decided on the name BodyMap?

David: John Maybury, who was my boyfriend, came up with the name. It was the title of a piece from the 1970s by an Italian artist called Enrico Job: 2,000 photographs of a body laid out flat so that you can see the front and the back.

Stevie: So it’s like a human skin.

David: A magazine – 19 or Cosmopolitan, I think it was – called us and said they needed the name of our company.

Stevie: And John had a whole list. He’d done a bit of research. I remember one of them was ‘EarthWorks’.

David: And we were like, ‘Where’s that list that John compiled?’ You were literally on the phone, weren’t you? And you were like, ‘What are we going to call ourselves?’

‘I loved the idea of that combination: something classical with something ethnic. If they’d only done club clothes, it would have had no depth.’

Stevie: We looked at the list, and we went ‘That one!’ And I said: ‘We’re called BodyMap.’ We never wanted our names, like ‘Holah and Stewart’. We wanted an umbrella name, because even at that point we knew we wanted not just clothes but head-to-toe dressing: accessories, tights, sunglasses – whatever. And we were also starting a healthy lifestyle. We had lots of friends who were macrobiotic and we started doing our own cooking, which led to recipes being published.

John Maybury: When David and Stevie decided to do their thing together, they were looking for a name. At that time, my own work was all about performance and body art, reacting to stuff from the 1960s and 1970s. I’d been making my Super 8 films that had funny pretentious titles. I was interested in Enrico Job. He’d drawn little squares all over his naked body, photographed it, and laid it out flat, like an animal hide. He called the piece Bodymap. I said to David: ‘You’re doing these stretchy, athletic-y clothes. It’s so perfect.’ Everything they did was so intuitive and random. I came up with some other names – something to do with ‘terra’ was one, ‘half world’ was another – all of them drawn from artists I was influenced by at that time.

David: When BodyMap started, John and I lived in Godwin Court and Stevie lived in Levita Court in Ossulston Street, down the road in King’s Cross. And that’s where we started BodyMap, in Stevie’s flat. Pattern-cutting in one room, machines in another, Stevie lived in two other rooms, and we had an office in the living room. We were getting everything delivered: all the fabric was going up the stairs, while the boxes for the shops were going down.

Stevie: There was no lift.

Tim: I’m looking for eureka moments, like April 1983, when you were part of New London in New York. [Reading from a clipping] ‘Susanne Bartsch put on a fashion show featuring 20 of the newest, most outstanding British designers… I went to see it two days before the show in a rather decaying room of the Chelsea Hotel… It was chaos. Susanne was on the telephone, organizing chairs, spotlights, drinks tickets and four high stools for the makeup artists… doing it on absolutely no money at all. She had lots of friends among the designers. She opened a shop and wanted more things and more designers.’ So Susanne showed Sue Clowes, Richard Torry, John Richmond, Rachel Auburn, Monica Chong and you, among others.

[Journalist] Richard Buckley: I want to say New London in New York was at the Roxy, that roller-disco place that was popular at the time. I don’t remember too much from the show other than that I was sure I would love Sue Clowes. I’d already gone to see her earlier in London. She had a studio in Brick Lane, back before it was fashionable to be on Brick Lane. She did all of Boy George’s outfits. But I was sort of disappointed. It was more of the same old, same old – but BodyMap and Leigh Bowery? Now that was something. It left my mouth hanging open. It was so fresh and vibrant.

Tim: What happened after New York?

Stevie: It made all the British press become aware.

Richard Buckley: Those were the days when traditional British publications like Vogue, Harpers & Queen and Tatler never ran any images or stories about young London designers; The Face and i-D did. I was associate fashion editor at Daily News Record, and I’d already written a big story about the New Romantics, Spandau Ballet and the D-Mob designers when they’d been in NYC the year before. And I wrote these people up as well. They’d never gotten any publicity at home, but here they were getting lines in an American menswear trade publication. Remember, there wasn’t social media or e-mail in those days. I had the London designers pretty much to myself in the US.

David: It was very well-received, when we came back from America the first time.

Stevie: And we felt we hadn’t done anything.

David: Robert [Forrest] was like, ‘You’ve done that there, why aren’t you doing stuff here?’

Stevie: Then, in October, we were part of the Individual Clothes Show at Olympia. That was when we showed the Olive Oyl Meets Querelle collection, which was the one that really made us realize we were doing something good. We got the Martini Award for being the most innovative young designers.

‘It was a new way of dressing, and it could fit a lot of people. You’d pull a skirt on and look a million dollars, but it was just a sweatshirt skirt really.’

David: It was a fabulous collection, when I look back at it. I remember [journalist] John Duka was there. And he was literally going bonkers over it.

Stevie: Richard Buckley, too. They were sitting there, saying ‘This is London. This is what we’ve been waiting for.’

Richard Buckley: I saw the Olive Oyl Meets Querelle collection at the first fashion week I did in London after moving to Paris in July 1983. In the mid-1980s, there was definitely something going on in London design-wise. There were so many young designers. On any Saturday you could go to Kensington Market and find someone who had spent the last week making clothes in their bedsit. Whatever they were selling always reflected what was going on in the clubs or, better yet, they were taking it one step further. It was all about the street and the clubs then. And the music. Fashion and music were so intertwined in the mid-1980s. Also, in those days every major design house in Paris and Italy was hiring students right out of Saint Martins or the Royal College of Art to come and work as assistants, because the students were the ones creating the trends. But what BodyMap did was very different to what everyone else was doing in London, especially as the look shifted away from the New Romantics. Their combination of an athleticwear aesthetic mixed with unusual silhouettes, colours and patterns made their clothes

unique. Polymorphous is a good word for it, considering how the pieces were easily interchangeable, layered and even androgynous – it didn’t make any difference if a man or a woman wore them.

Tim: How long was your show slot?

David: Three or four minutes. We showed 10 looks and all the models looked hot! It was all girls who were on the scene at the time. Gary, our gay cleaner, was our Querelle, and I was in it. We had the Querelle look, and the girls had the Olive Oyl look. The styling was just out there! There weren’t stylists in those days. We did it all: the earrings, the hats, the gloves. The whole thing, top to bottom.

Tim: The totality of the thing is immediately striking – it’s like it landed on Earth fully formed.

David: I wish we had a film of that show. We just didn’t have a camera. But our four minutes really made an impact. And afterwards, we all went off and sold on the stand.

Tim: Did you feel like everything had suddenly changed?

David: There was a buzz. An overnight sensation, I would say.

Tim: You were making the clothes in your flat?

David: Some of them, and we had the rest made outside in factories.

Tim: And the quality was good?

David: It was quite hard because people hadn’t seen Lycra before, and the finishing of the hems wasn’t always OK.

Stevie: Sometimes, when we look at the archive, we’re a bit, like, ‘Hmmmmm…’ [raises eyebrows]. But the main thing was that we had to think about how we were going to manufacture, because we weren’t backed by anyone and all the money was forward-financed. You had to have the money to pay for the fabrics and for the things to be made. We went from the £3,000 Robert Forrest order, and then the mid-season orders and the orders from New York for the dishcloth bits got us to £15,000. But with Olive Oyl Meets Querelle, it shot up to £85,000. That was one of the reasons we said yes to [fashion entrepreneur] Adriano Goldschmied.

Tim: How did he come into the picture?

Stevie: When we first met him, he had the Genius Group working with Katharine Hamnett and Vivienne Westwood. So Katharine was designing the Goldie collection and she didn’t want to do it anymore, and David Mantej from Diesel and Evelina Barilli had taken over but Adriano wanted someone new. He knew Lynne Franks and that was how, practically overnight, we ended up in Italy. One minute we were in London, the next we were in Asolo. And I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is

where Dame Freya Stark lived.’

David: It was really beautiful, but we were put in a box…

Stevie: …and we weren’t allowed to see anyone else. Because Adriano had taken Dave and Evelina off Goldie and put them on Bobo Kaminsky, and he didn’t want us all to meet up. Then in comes Evelina, the pattern-cutting queen of Italy, our best friend from that day to this, and she takes the four of us to Venice and we all become friends.

‘Whatever they were selling reflected what was going on in the clubs, or taking it one step further. It was all about the street, the clubs, and the music.’

Tim: Here’s a ‘new faces’ piece from the Sunday Express magazine, January 15, 1984. The writer calls you ‘BodyWrap’! [Reads] ‘Cashflow is helped along by their first earner, a still-thriving market stall.’ You’re the ‘new faces’ of fashion and look who they chose for architecture – Zaha Hadid!

Stevie: Then the next show was in March 1984: The Cat in the Hat Takes a Rumble with the Techno Fish. We were the hottest ticket in town that season. It was our first solo show and that was when Lynne Franks started the Murjani tent at the Commonwealth Institute. She’d been doing our PR since Querelle. We had the best slot: Friday at 7.30. We hadn’t slept for days.

David: But because we’d done Querelle before that, we’d kind of set the pace.

Stevie: We used some of the best-sellers from Querelle: the petal skirt, the casual cardie, the one seam, some of the parkas and the sweep.

David: The iconic BodyMap looks.

Tim: What pressure did the success of Querelle put on you as you approached Cat in the Hat? Did you feel liberated by the sense that you now had an audience? Or did that scare you?

Stevie: Because it was our first solo show, we had to have a marketing plan and plan all the outfits.

David: Which we hadn’t before.

Stevie: Well, we had, but this was a whole show.

Tim: So here you are, planning your first solo show, and you’re the one everyone wants to see.

Stevie: When did Mikel Rosen come into all this? Was he helping already?

David: Yeah, he was.

Stevie: He got the dancing twins, Barry and Nick Kamen. We knew Barry, and Nick came with him to the casting. We had our own auditions, do you remember? In the council flat on the third floor at Levita House, which was filled mostly with mad people and Asian families. And there were all the people queuing up the stairs, and we could only pay them a £75 clothing voucher or something like that, because we didn’t have any money.

David: There were quite a lot of people in the show, but we had no idea where some of them had come from. Mikel found some good freaks.

Mikel Rosen: Stevie found these two black guys tap-dancing on the Tube. I found the Kamens through [Storm Models founder] Sarah Doukas because Laraine Ashton was representing them. Boy George was supposed to sing, but couldn’t, so Helen Terry stepped in. We had people coming out from the right and left sides, five models at a time, the Kamens in boxer shorts. It was a totally different way of putting things on the runway: real people, no choreography, no running order. Jeffrey [Hinton] was bunging tapes in and out of the cassette machine. If models were going slow, he’d put on a faster track to make them move more. There were no headsets. I was signalling to someone in the doorway to send out the next models — all with hand signals! But that energy, and the prints, and the club-scene clothes is what the Americans went wild about.

Tim: Did the models have to change?

David: Three times!

Stevie: In those days, you didn’t do the one-outfit-one-model thing. You had to work it.

David: You had to come back and get changed for that £75 voucher!

Tim: Sounds like a long show. They were all long in those days.

Stevie: It was half an hour, maximum.

David: We had about 80 outfits and so much happening. And Jeffrey doing the music.

Tim: Do you remember the music?

Stevie: The theme song from Flipper at the end, because we were very conceptual! And Helen Terry at the beginning doing her a cappella, something like ‘BodyMap presents to you – their first collection.’ She came down the catwalk singing. She was with Culture Club at that point.

David: Then it was all just hits from the time that we loved. There was Eurythmics in there, I remember. It was all those fabulous songs of the time.

Stevie: People were fighting to get in. Lynne [Franks] had to manage that whole thing. She was wearing Olive Oyl Meets Querelle. I remember her standing up on a chair in the full outfit.

Tim: Was she encouraging the chaos to create an event?

David: Yeah. I think she made it into the thing it was. She squeezed in as many people as possible to get the vibe going. She was good at that. It was a real happening.

Tim: And you backstage, screaming?

David: Doing the outfit changes! I was making sure the outfits were getting put on the right way around because people didn’t really know how to put these things on.

‘The next show was in March 1984: The Cat in the Hat Takes a Rumble with the Techno Fish. We were the hottest ticket in town that season.’

Tim: And were you still with John at this point?

David: Yeah. John made this amazing backdrop with fish jumping.

Stevie: Everything was so conceptual. The Cat in the Hat Takes a Rumble with the Techno Fish describes our influences in that collection. We set ourselves a theme and that helped us to design. So, obviously, the Cat in the Hat goes with the funny gloves and the stripes, and then the techno side was where we did the styles with the big mesh print. And Rumble Fish was a film that had just come out with young actors in it. It was in black and white except for the scene with the two fighting fish, which was in red and blue, and that inspired us to do mostly monochromatic with splashes of colour. From that concept, John painted a fish backdrop, Jeffrey played the Flipper theme at the end, and the models had fish-shaped stickers on their faces.

David: And one glitter eyelash. It was fabulously conceptual, and so polished. We did a shoot for ourselves to start with. Iain [R.Webb] came to draw the collection, so we got an idea of what it was going to look like with the makeup and hair. Because it was sculpted hair, and with the Cat in the Hat hats and all the other stuff, we had to know it was going to work.

Tim: And everything was for sale? All the hats and the gloves?

David: Everything. We did amazing sunglasses and they sold really well. Often, we would do a shoot beforehand.

Tim: Did you have rehearsal time?

Stevie: A tiny bit, so Michael Clark could run through what the models would do. They just ran on and danced.

Tim: Who were the models who were most identified with your shows?

David: Susie Bick, Amanda Cazalet, Lucy Tear… Hilde Smith, who did all of our prints, was in all the shows, too. We don’t know what happened to her. And Les [Child] is my friend, so he was in all our shows.

Les Child: Yes, I did every show. It was quite overwhelming, I didn’t realize I was so integral until after the fact. We were all very close. I was in Stevie’s graduation as part of Masai, an all-black dance group. If you were good at singing or dancing, David and Stevie would try to use you in some way. They kept up that family spirit to the end. My fondest memory of the shows – and I was very lucid and together in those days [knowing laugh] – was the whole preparation: all these incredible children getting ready backstage, the madness, the excitement, the photographers all around the catwalk instead of just at the back. It was much more of a performance, with the audience screaming, ranting and raving. Very clubby. It was a constant party. We got so much attention when we went out that getting attention onstage was normal. People did things out of passion and love. If they got paid £50, they’d be excited: ‘My God, let’s go and get a drink.’ Maybe it was an overflow from the 1970s, the sense of freedom and love. Maybe that comes with being young. But we just loved being out around people. It wasn’t about money or who you were. No one had an agenda. The industry wasn’t saturated with endless stylists, makeup artists, hairdressers, the way it is now. Now people have to have an agenda to get somewhere.

Susie Cave (née Bick): I fell in love with David Holah and Stevie Stewart at first sight! Michael Clark was wearing BodyMap, and he was dancing so beautifully and looked amazing. The clothes were very sexy, in a wild and wonderful way, with both boys and girls wearing the dresses. It was so different from anything I had ever seen. It was such an honour to be asked to model for something that was so risky and forward-thinking. But the atmosphere was that of a family, with great loyalty between them all. Lesley Chilkes did the makeup for the shows, and her mum was on the catwalk with Stevie’s mum.

Tim: After such a huge show – the last one, on Friday night – did you all go out and celebrate?

Stevie: Didn’t we have to go and sell again? Or set up for the next day? We were very hands on.

David: I think we went and set up and went home, ready to sell the next day.

‘BodyMap shows were much more of a performance, with the audience screaming, ranting and raving. Very clubby. It was a constant party.’

Tim: At that point, were buyers coming from everywhere because of BodyMap?

David: Before that there weren’t that many buyers in London. We drew them back, and a lot of fashion press from abroad. Things started to really kick off for London again after that.

Stevie: With Cat in the Hat, there were nearly £500,000-worth of orders. We had to have money for manufacturing. We were, like, ‘How are we going to afford to make this?’ So we signed an American licence deal and a Japanese licence deal, and at the same time we were doing Adriano and Via Vai, weren’t we?

David: It was a huge amount of money in those days, and so much money went to paying for BodyMap. We were making quite a lot, but we ourselves literally didn’t have any money.

Stevie: We paid ourselves £50 a week.

David: That’s what we lived off, and I think we paid our rent out of it. But, you know, I was in a council flat so it wasn’t much money. In those days £50 was quite a lot. We were never earning masses of money, but we were living the lifestyle for the next few years, getting on planes to New York and Japan and Italy every other weekend. We never stopped.

Stevie: And after Cat in the Hat came the next collection for Spring/Summer 1985: Barbee Takes a Trip Around Nature’s Cosmic Curves. This was where we had all the models changing on stage, so we had backstage onstage. It was all a topsy-turvy concept.

David: And we probably pushed the boundaries just a bit too much, with the people changing in front of everyone. We did these amazing nylon Lycra swimsuits that were totally ahead of their time, but people just thought it was S&M bondage gear.

Stevie: They were just Lycra, like American Apparel. I think they thought it was PVC. But people still use it today. It is still the swimwear fabric.

Tim: Was this show less mad?

David: No, there were tons of people.

Stevie: And we sold lots as well.

David: We just got really dissed for it. The American press turned on us. We went from being the sweethearts of fashion to being the demons. Models were smoking on the runway; the girls had bald heads or big Afro wigs. It was quite 1960s-inspired. All the boys wore girls’ clothes and all the girls wore boys’ clothes. Stickers on nipples, bosoms out… It was quite a rad show.

Tim: A big change from the one before?

David: Huge! It was really out there. I mean, I thought it was amazing.

Stevie: It was at the Natural History Museum, Friday, October 12, 1984, at 7.30.

Tim: A very specific memory! Did the show feel like a natural evolution?

David: People didn’t respond as we thought they would. We were pushing it a little bit, but nothing that you wouldn’t expect. We did have some PVC aprons, like bondage aprons. The American market just took it the wrong way, really. My five-year-old niece who was always in the show was a beautiful little baby and she was always naked, but people were getting changed near her and the Americans didn’t like it.

Mikel Rosen: The Cat in the Hat was such a thing that they thought for the next show: ‘We’ll take the back wall away and show everyone what goes on backstage.’ So I had this gang of 70 kids backstage – some with no-hair, skullcaps, some with huge Afros, most weren’t models – but by now some people from Cat in the Hat had a profile, like Amanda Cazalet and Felix, the kid who’d done a Madonna video, so I had a few prima donnas backstage, and when I called them they wouldn’t come forward. The merchandise wasn’t showing properly: there was no flow; there was a lot of jumping and running. It was a complete nightmare and it was all being revealed to the audience. And the Lycra looked liked S&M bondage gear. It wasn’t done that way – it was much more Kinky Gerlinky – but this was before anyone had seen this in fashion. It was before Gaultier did all his S&M looks, so there was a load of criticism. There was no drop-off in orders, but from that point on, David and Stevie were being watched.

Tim: How did the audience respond?

David: Everyone else loved it! It worked beautifully. But everything had turned on its head. It was a different mood. We were inspired by what was happening around us.

Tim: What was happening around you?

David: Drugs.

Stevie: There was lots of heroin.

David: It took a turn for that dark feel. It was darker in its lighting, and darker on the catwalk.

Tim: Were people dying around you?

Stevie: Yeah, people that we had on the catwalk in the Barbee show did die.

David: Not at that time, but later on. It was the heroin chic thing, That’s basically what we were doing back then.

‘We paid ourselves £50 a week but were living the lifestyle, getting on planes to New York and Japan and Italy every other weekend. We never stopped.’

Tim: Was it a problem for you?

David: I was taking heroin at the time. Stevie wasn’t though.

Tim: Did you feel this joyous edifice you’d created was crumbling?

Stevie: I don’t know what I was feeling. I do remember Elsa Klensch interviewing us after the Barbee show and me thinking, ‘Don’t say anything, David!’

Tim: Have you talked about it much since that time?

David: What, the drugs? No, not really. We’d all had the drugs experience. Stevie hadn’t. She had hers later. I got mine out of the way a bit earlier. I did get into the heroin chic thing at that time.

Stevie: Luckily, you didn’t get addicted.

David: I didn’t get addicted, thankfully, but then I wouldn’t have done because I’m not like that. But a lot of them did go on to become fully-fledged junkies.

Tim: Stevie, were you worried? It’s not easy to watch your friends slip away.

Stevie: I remember Lynne saying: ‘You’ve got to do something.’

David: Because I was out of control. But I was just experiencing a thing at the time. It was only for that season.

*John Maybury: Though BodyMap was fashion, it was as responsive as a news report. In a funny way, it was a kind of journalism. The world Stevie and David were showing was the way they were living.

Stephen Jones: That whole time was set against the background of this weird new disease coming from America. People knew people in San Francisco or New York who were dropping like flies. We didn’t know if tomorrow was going to come or not, so what had been this wonderful, magical phenomenon started to crack apart in the most unpleasant way. That very optimistic life we’d had was cut short, and you could see what a very strange time it was by looking at the fashion, whether it was BodyMap, Rachel Auburn, Richard Torry or Leigh Bowery.*

Tim: But massive, rapid success followed by crash and burn is the kind of story people relish if they’re jealous. Did you get the impression that people wanted to take you down a peg?

David: Of course, that was what it felt like. I mean, it was just a taste of that, and it coincided with what we were doing at the time. But the next season was the Half World collection; all very tame and much more tailored, as a response to what had happened before.

Stevie: The Half World, inspired by Dorian Gray. Still quite dark though!

David: I wasn’t into drugs any more; it was just the flavour of that moment.

Stevie: We signed the American licence between Barbee and Half World with a company called Design Consortium. One guy had been with Calvin Klein and they were like all-round rag-trade people. But it was a difficult deal. They couldn’t make BodyMap because of the cost of importing lots of the fabrics from Europe, so in the end we had to make BodyMap for wholesale prices, plus a small percentage. It was really horrible to do that because it was so much more work but for not much more money. They did do well for B-Basic. That was our diffusion line, which we were making with a company in Leicester. There was also an American B-Basic in stretch jeans, with our prints and little turtlenecks and polo necks and twoby-two and one-by-one ribs. They could make that in El Paso, and they had some factories and distribution in the Amish district in upstate New York.

Tim: How long did that deal last?

Stevie: Three years.

David: It started out quite well. It was like we moved into a slightly different gear. We were staying in fabulous hotels and driving about in limousines.

Stevie: We were in upper class on one of the first Virgin flights to New York, which was amazing. Staying at Morgans. The hotel didn’t have a licence, so we used to phone up for Champagne and they’d get the doorman to go to the shop to buy it for us.

David: And Steve Rubell, who owned the hotel, took us up to the penthouse and we partied. So we were living the high life after Barbee.

Tim: Your new partners weren’t flustered by the American media response?

Stevie: No. We had that licence and the one in Japan which we signed with Isetan. So we were in Japan, New York, Italy. We were never at home.

David: Our feet didn’t touch the ground. We were literally in and out all the time.

Tim: And there was 18 months of that between Cat in the Hat and the next one, Is a Comet a Star, a Moon, a Sun aura Racoon?

Stevie: The Design Consortium was a bit of a problem, because they oversold BodyMap. We were selling on our own to the best boutiques when Lynne was our PR, and we got our first American stores ourselves. Then, after Barbee, we signed the deal, and the Americans started selling it but they would sell it too close to other shops.

‘That time was set against the backdrop of this weird new disease coming from America. People in San Francisco or New York were dropping like flies.’

David: At first it was fabulous, and then it kind of went sour.

Tim: When was Taboo?

David: It was during that Barbee time, because I remember us going.

Princess Julia: They had great successes, but the reality was that people were all over the place. MDMA was emerging; heroin affected a lot of people. People used different things as coping mechanisms. Taboo was a particular sort of club that was one of the more extreme spaces. Obviously, everyone was encouraged to get dressed up. Leigh [Bowery] was doing his own collections, evolving. BodyMap was considered a successful design team and it was quite established as a brand, with a whole company by then. They were exploring other collaborations – working with Michael Clark, for instance. David LaChapelle was part of the BodyMap gang. He was a go-go dancer at Taboo. The place was so bonkers that I wondered how they got up to go to work. It’s true that Jeffrey played the slipmat. People were dancing to this horrible grey noise. Leigh came running up and said, ‘Jeffrey’s playing the slipmat. You have to stop him.’ So I went up and told him he was playing the slipmat, and he said: ‘Oh yes, I’ll have a cup of tea please.’ He was tripping, and I think he thought he was at home. Then it dawned on him.

Stevie: Also, we were working with Michael Clark at the time.

Tim: How did that start?

Stevie: He came to us when he saw Cat in the Hat. We did the unitards with long sleeves. We did rubber chaps and frilly skirts for him.

Tim: Were you always a dancer?

David: I loved ballet and dance; I used to go to ballet classes. But we knew Michael from the club scene – Taboo and the Bell in King’s Cross. He was friends with Jeffrey and other friends of ours. He liked BodyMap; we gave him some bits to wear, and then he asked us to design a collection for him.

Stevie: Do You Me? I Did. It was the stretchy mesh rubber bits. And David and Michael became boyfriends.

David: John had gone off to New York to start his art career. He was with artists there, and he never came back. So, I was a bit like, ‘Oh, OK, whatever’. And then Michael came along so I started hanging out with him. And I became close friends with Leigh Bowery because he was in Michael’s company. I think we actually met him in Kensington Market, because he would work on Rachel Auburn’s stall with Trojan. There were three of them, Leigh, Trojan and another guy. I’m very bad with names. They all looked the same, like the three kings.

Tim: I imagine you must have been quite an intimidating clique. Actually, that is very valuable with a fashion brand – having a group of people who embody what it is you do and who stand by you. Especially if they’re all doing amazing things like Taboo.

David: People were around us but we never saw anyone beyond our circle. We didn’t really integrate. Most of it stemmed from Warren Street and old friends. In Taboo, we were always in our group: Jeffrey, Julia, John… well, actually it was Michael at that point.

Les Child: When David and Michael got together, there was so much gossip. I was at [stylist and writer] Jerry Stafford’s place in Paris and Sue Tilley called to tell us. They were unbelievably in love. And there was a whole group of girls in love with them, at their beck and call. We’d go out to a club, or to the Bell, and everywhere they went, the whole club followed. They’d be snogging at Heaven, and everybody was around, being present. It’s like when Kate Moss walks in a room today – the whole place moves. New York was calling – all the clubs trying to get Michael and the London scene over there. But then after Barbee, everything became very insular and clique-y. Everybody disregarding everybody. It was a form of bullying.

Tim: Do you ever wonder if there was a time when success went to your head?

David: When we were out, we would dance and have a fabulous time. But I think we were working so hard, it literally felt like we’d worked an entire life in those few years. It was 24/7. And because we were always on a journey or a flight or coming back, we would go out and have a good time and then go straight back to work.

Stevie: We were too busy to really realize what was happening.

David: We were just trying to make the money to cover the manufacturing and another collection that was pretty imminent. Plus, we were literally every other weekend in Italy, making sure that was going OK.

‘They had great success, but people were all over the place. MDMA emerging; heroin affecting people. People used different things as coping mechanisms.’

Stevie: We designed the whole collection for Goldie. We learned an incredible amount there because we had to deal with all the agents from all the different countries. We’d pin the designs up on boards and get feedback from all the agents, which was really an incredible education, and that helped us learn how to market our collection.

Tim: Maybe you were prepped for it because you’d been so practical for so long before you reached this point.

Stevie: We’d already worked while we were at college.

David: And we were pretty resourceful. We could pull it together. When they put us in the Goldie box, we were churning that stuff out.

Stevie: We were like design computers.

David: That discipline really filtered into Barbee. I mean, it was just beyond. There was so much stuff.

Stevie: We could have done about six collections with all that; it was such an explosion of ideas, and fabrics and options.

Tim: Did you have any sense of being standard bearers for the whole scene in London?

David: I don’t think we ever really stood back and looked at what was happening. One day just melted into the next. It was our company. The people who worked for us would go home about 6pm, but we stayed all night and had meetings. We just had to do it.

Tim: Did you have a sense of the long term at this point?

Stevie: We wanted to.

Tim: What would it have been?

Stevie: Just to carry on.

David: I suppose we thought that what we were doing would make that happen, so we worked hard to make it continue. When we went into troubled times, we still worked to try and pull it out.

Tim: You said Half World was a reaction to Barbee – a kind of consciously safer option. That suggests an evolving commercial awareness.

Stevie: We did try to tone it down a bit for Half World. But we had the American licence and we did a denim section in the show for them, and they must have given us some money towards it. We did stretch denim and machine knits too, like Cat in the Hat. The same design motif on the hand knit and the machine knit.

Tim: And how did that collection do?

Stevie: It did well. I can’t quite remember – I’ll have to look at the sales charts. Then it was Isa Comet, which was a really big production in the Natural History Museum, with lasers and Boy George in the audience. And we showed B-Basics. Jeffrey was still doing the music. And we had God knows how many cameras: John Maybury, Cerith Wyn Evans, Judy Blame, Sophie Muller, Steve Chivers. Maybe five or six cameras of our own to record the whole thing as a film.

Stevie: Isa Comet was followed by Tudors, but then came the money problems.

David: It wasn’t really Tudor. It was more Georgian.

Stevie: We were using viscose Lycra then, and sportswear-y fabric. You can see the development from when we started. It was more towards taking sportswear fabrics like nylons and rubberized cottons and putting them into design shapes.

Tim: Did the money problems make the work a chore?

David: Yes, because we had to work to make it succeed.

Tim: While you were wondering where it all went…

Stevie: We weren’t ever rich. The Americans in their first year sold 1.5 million, according to this telex paper in the archive. So we got our royalty on that. I guess we were sort of in the middle.

Tim: Were you ever in a position to buy yourself a flat?

David: No, no.

Stevie: We were going to buy something together.

David: It was only £30,000, but in those days, that was a lot of money.

Stevie: We just put everything into the business.

David: It’s a shame. But no, I had a council flat and I’ve still got it.

Tim: What, the same flat?

David: It’s a different one. We got housed after Warren Street and then we got council flats. Jeffrey still lives in the original one we got.

Tim: With all his records?

David: They got a three-bed flat. They were downstairs. Julia and Stephen Jones lived in that one, then Stephen moved out and Leigh moved in. Then Julia moved out and Leigh died, and Jeffrey still lives there with his records.

Tim: And you and Michael – what happened? Did that last very long?

‘We didn’t try and fit into the fashion mould: the networking, building the brand, milking it to the max. We’re just not that type of people.’

David: Two and a half years. He was doing his world tour and I went with him.

Stevie: And I was left here dealing with the problems of the sinking ship!

David: Because by then BodyMap was on the downturn.

Stevie: So David was off gallivanting around the world…

David: You’ve got to live your life, haven’t you?

Richard Buckley: I really don’t know any of this for sure, it is all conjecture, but I believe BodyMap became a disposable product of the fashion system: they were made into stars and then discarded. It was a strange ‘rise and fall’ period in London. I remember one designer who showed so much promise with his menswear. Eventually, the Japanese were investing in his business, or he was designing there, I’m not sure, and I saw him out at Madame Jojo’s in the fall of 1986. He was wearing clothes by Yohji Yamamoto. He had finally made a little money and was buying ‘designer’ clothes instead of wearing his own clothes. The last time I saw him, he was designing accessories for a menswear company, and not under his own name. There were lots of stories like that during the end of the 1980s. Stevie and David were another story altogether. One minute, they were young people expressing themselves through fashion, the next they were the darlings of the fashion world and London club society. As the business grew, so did the constraints of expansion and production. I think it was all a little much for them. There were no safety nets, then. Also, what got back to me is that there were a lot of heavy drugs and David wasn’t running the business at 100 percent. Believe me, I cared about the two of them a great deal. I really wanted them to succeed.

‘BodyMap became a disposable product of the fashion system – made into stars then discarded. It was a strange ‘rise and fall’ period in London.’

The End

Tim: Was there ever a time for the two of you when you felt like you had drifted so far apart that you’d lost touch…

David: Well, I was in Australia…

Stevie: We were always friends. We were always going to work together.

David: Yeah, we’ve stuck together. We’re still friends. Stevie gets me involved in projects sometimes, and so, yeah, it works like that. But our work is different now.

Tim: If the BodyMap book and the exhibition happen, it’s an opportunity to come back together and put a seal on the way you want history to see you.

David: Well, I guess that’s the reason to do the book.

Tim: I’m surprised it hasn’t happened already.

David: We’ve had a few things in the pipeline – like a Comme des Garçons thing or a Stüssy thing – but then they came to nothing.

Stevie: At one point, H&M were interested in doing a collaboration.

Tim: Do you think you have a reputation?

David: No, not really. Not like it was. I might have had a bit of an attitude back in the day.

Tim: Even if you did, the statute of limitations would have run out on that long ago. But bright young things do piss people off…

David: I was just busy, getting on with doing stuff. Maybe I did have an air of being ‘busy’. Maybe I just didn’t have enough time for other people. I’m not like that now. I was too busy then.

Tim: How could it have been different, do you reckon?

Stevie: You mean the moral of the story? When Joseph turned one of his shops in South Molton Street into BodyMap, I think we should have been more aware of how brilliant that was and tried to work with him more. It was only going to be a one-season thing for Cat in the Hat, but we could have made it long-term.

David: It had amazing press. The shop was fabulous. We should have learned, but we were ‘busy’!

Stevie: Then Lynne Franks wanted to open a Biba-esque shop. We had the head-to-toe dressing and the lifestyle thing, the healthy eating.

Tim: When was that?

Stevie: This was when we had money problems, and she was, like, ‘Why don’t we do this? Get a shop in Covent Garden and do fashion and lifestyle, be very ahead of our time.’ But we were too scared at that point and we had no money.

David: I suppose it’s that commitment thing. We didn’t commit to the right things at the right time, and we didn’t have a backer. Well, we did, but it didn’t work.

Stevie: Our worst thing was the American licence. They owed us money. Not a million, but a lot. A big Swedish-Icelandic distributor went under and they owed us £35,000 or something. Then the cotton fabric from the Swedish factory we’d worked with from the beginning went wrong. In the shops, it laddered on the seams. It had needle penetration problems, so we had to recall all of that. In a small period of time, everything went wrong.

Tim: And where was all of this in your show schedule?

David: There was a period when we didn’t have a show.

Stevie: Wasn’t it in between Tudors and BodyMap-ism? It was that period 1987-1988. We had a blip, then we started again. Strawberry Studio – George Hammer and Bryan Paradise – took us under their wing, as backers, but that didn’t last. We bought the company back from them and we started again. We had a few intermediary seasons where we still sold, we still produced, but we didn’t have a major catwalk show. The major show after that was Life is… That was 1989/90. And then we did Moon in 1990, which was after my mum died. We dedicated that show to her. Then we carried on with our little shop in the front of Hyper Hyper and a few wholesale bits, but by this time the recession had hit. By about 1992, we were thinking: ‘Let’s call it a day.’

David: And that was the end. It was 10 years, but it felt like 500 years.

Stevie: We said no to Adriano as well, didn’t we? We did have people approaching us to back us, but the generation above us, Katharine Hamnett and even John Richmond, Stephen Linard, they had had problems with backers and so we were a bit wary. It wasn’t like it was in the 1990s where you went to a company that did the manufacturing, the distribution, the sales and the PR out of one company. It was like individual people backing you, if you know what I mean. Peder Bertelsen was interested at one point.

David: It was all a bit tentative. It’s a shame, really. Imagine if it had still been going – we’d be rich by now! Rich! Rich! The other thing about us is that we didn’t connect with the fashion thing. We didn’t try and fit into the fashion mould; we were too busy doing our things. We didn’t go into that fashion marketplace and do the necessary myth building. I think that’s another reason. The two of us together don’t do that: the networking, building the brand, going into all the forums, milking it to the max, pushing ourselves forward. We’re just not that type of people, unfortunately. Otherwise, we probably would have made more of a thing of it. We would have made sure we were locked and set in place. But we were under a lot of pressure. We’d been through a lot.

Stevie: Yeah, and then I nearly lost my mum’s house.

David: Stevie’s mum had died. It was all the end of a story really. Picking up the pieces seemed too much.

Tim: Do you ever feel that you were ahead of your time?

Stevie: Oh, yeah. Too ahead of our time.

David: Our biggest problem.

Stevie: The Barbee collection – there were so many ideas. We could have optimized it and slowed it down.

David: We could have done with a good manager who worked with us and not against us. If Lynne could have been our manager then it might have worked, but that wasn’t her thing. We worked well with Lynne. If she had managed us that would have been the key, because then she could have directed it in the specific way that it needed to go. You know, the lifestyle and all the ideas we had for everything. She could have pinpointed it in a more direct way. Instead of giving it all, she could have helped us hold back a bit. Spread it out a bit.

‘BodyMap has stood the test of time. You can see that in all the designers now who collect their work, and who are inspired by them. It’s not nostalgia.’

Or Is It….?

David: I have to leave at 5pm, because I’m teaching.

Tim: What are you teaching?

David: Printmaking. All different techniques: lino, etching, wood cuts, block-printing – everything. I try and incorporate everything. I teach a lot of beginners. We make nice little prints. Usually, it’s only five-week blocks, so they need to find out and get inspired…

Tim: Is it satisfying?

David: I’ve been doing it for quite a few years now, and, yeah, I do enjoy it. I teach textiles, too. Silkscreen printing. It’s quite varied. I get to see lots of different people. I teach at City Lit and Morley College. I also teach BA students at a college in Canterbury.

Tim: Did you ever imagine that is what you would end up doing?

David: I used to teach fashion a lot.

Stevie: We both taught. We’ve taught Phoebe Philo, Hussein Chalayan, Giles Deacon. They were all in a second-year project that we did at Saint Martins.

David: I just worked with Giles again recently. I did some Tudor-inspired prints with him. It was nice to work with him, because we’d taught him years ago. It was really nice to be brought in for that. Although I’m not doing fashion now, it is quite nice to just dip in. Stevie is still involved with clothes-making and she gets me in sometimes. I didn’t think I would be a tutor, but I like it. You know, it’s not like every single day, so I have some space to do my own thing. I did a little scarf project with this company and then it all went horribly wrong.

Tim: But the scarves are so beautiful.

David: They weren’t fashion. We did the scarves and then they wanted to make clothes. They wanted to make a parka, a dressing gown, and this and that in silk and stuff. It could have been really lovely and beautiful, but they didn’t fully understand how to make and develop things. They became a bit tiresome and I still hadn’t been paid, so I was, like, ‘OK, I just can’t do this anymore. It’s too much, too much.’ It would have been lovely if it had been easier.

Stevie: We did do a lovely parka; I helped David on the clothes side.

Giles Deacon: When I started at Saint Martins in 1989, BodyMap meant everything to me. They were the thing you dreamed of being in contact with. So when I was lucky enough to have David and Stevie as external tutors in 1990, it was like having proper legends coming in. Every student was pulling out their best looks to come into college. I remember the project so clearly. I’d done these sketches of everything that was a play on words – pencil skirt, mini-dress – and they really got into it. David made it easy, and kind of pop, which was very good for me because I was overworking things. He made me think about movement: interacting with bodies, styling it on dancers, imagining the clothes on the street, and which club you would like to see them in, or would it be a gallery or a market? It was wonderful being able to bring David in to design some prints for my Spring 2016 show. They were incredible – modern Tudor, transvestite pagan! He had the same wide-eyed openness, the same incredibly perceptive take on style and culture. I think BodyMap has stood the test of time: its look, its technique, its iconography was so ahead of its time. In fact, its spirit is of no time. It still resonates. I don’t think of it as a failure. The relationship between fashion and commerce hadn’t worked itself out then. Given another 10 years, everything would have been different. Everybody who knew David and Stevie has this kind of obsession with them. They created a phenomenal body of work. You can see that in all the designers now who are collecting their work, and who are inspired by them. It’s not nostalgia.

Tim: Can you see your influence?

Stevie: Yes! During the time of BodyMap, Benetton copied us, Laura Ashley, Miss Selfridge copied us.

David: Everyone copied us and they still are copying us.

Stevie: A few years ago, the last D&G show was inspired by us, Stephen Sprouse and someone else in the 1980s. It was so BodyMap.

David: As an influence, we have definitely held our own. BodyMap is very influential.

Stevie: And just our pioneering use of all the Lycra fabrics. I mean, we did invent those.

David: We changed the way that people dressed, which is another thing. And the way we presented stuff. We were so ready to give all of our time to the work. We gave those extra hours to it to carry that dream forward, but, in the end, it didn’t happen. Which I suppose for both of us has been quite a big disappointment.

Tim: Did you feel defeated by it?

David: Yeah. Especially because Stevie lost her inheritance.

Stevie: My half of the money went to pay off the BodyMap debt.

David: So, it was a big thing. All that time. I know we’ve left our mark and that’s why it would be good to do the book. Then it’s done. It’s in there.

Tim: It doesn’t buy you a boat in the Bahamas though!

David: No. I still earn about 80 quid a week!

Stevie: Exactly.

Tim: Well, we are going to change that, goddammit!

‘Dreams, like people, can die. Memories fade. But looking back now we have to acknowledge the unique and uncompromising vision BodyMap always had.

The Envoi: From a Couple

of Fashion Sages Who Lived It

Alongside Stevie and David

Jerry Stafford: It was all very exciting and new at the time, and it caught the fashion world’s attention, which, aside from Vivienne [Westwood], had really been starved of an ‘intelligent’, culturally resonant fashion movement and performance-driven presentations since Ossie Clark’s happenings over a decade before. And the excitement really was those shows! They were provocative, camp, eclectic, theatrical mise-en-scenes, combining performance, dance, and true punk chaos. They deconstructed the conventional academic show format and replaced it with a spontaneous, diverse, gender-provocative display of narcissism and narcotics. It was perfectly of its time for the members and followers of the BodyMap cult, but probably way ahead of its time for most other people. And therein lies one of the challenges they always faced: BodyMap was, possibly, just too visionary. In retrospect, I think they just had too much to say, too much to express, and maybe the messages got lost. Lives got entangled and life took over. AIDS reared its ugly head. Drugs. Shit happened in the late 1980s that wasn’t conducive to the innocent, arrogant hedonism of the disco family lifestyle that fuelled their spirit. Dreams, like people, can die. Memories can fade. But still – looking back now from our gender-fluid, PC, diverse, all-inclusive, self-congratulatory plateau – we have to acknowledge and celebrate the unique and uncompromising vision they always had.

Stephen Jones: I knew David and Stevie because we went to the same clubs, and also from Warren Street. In that way that people from London thought Duran Duran were quite exotic because they were from Birmingham, we thought David and Stevie were exotic because most of us went to Saint Martins and they’d gone to Middlesex Polytechnic. And then they were BodyMap! They were so famous! What they did was so different to what everybody else did. When we were staggering round in taffeta, they did it in cotton jersey with a zip up the back. Overlocked jersey stretched out to make skirts with frill, upon frill, upon frill, so they just kept moving. It was fantastic! And it was for everybody – wearable, not expensive. It was much more like Biba than some kind of fancy designer label. And it was absolutely magical. That’s the word I would use. Michael Clark doing the rain dance at the end of every show; Stevie’s mother and David’s little niece Nico would come out on stage; the audience jumping up to join in; and Hilde’s prints of signs and tarots and magical symbols. Taboo, Leigh Bowery, these things have somehow lasted. I don’t know why certain things last and certain things don’t. Fashion has a very short memory. And it changes. Suddenly there was Margiela and Helmut Lang and a whole new ethos that was not about the party and having a fantastic time and the magic of performance. So, in a way, BodyMap was no longer relevant. Which sounds cruel, because they were so relevant to a whole mentality, and so successful at encapsulating that mentality and that moment, that, when it passed, they got passed over, too. That’s partly why I think people perceive BodyMap now as being so integral to the 1980s. And don’t forget that what went parallel with them was a total change in journalism, from the old-guard magazines like Vogue and Harper’s, to i-D, The Face, Blitz. Those magazines were their vehicles, and they helped hundreds of thousands of 16- and 17- and 18-year-olds to grow up with a completely different sense of fashion. When you look back, BodyMap was really representative of all that. They had this big office and people used to go and hang out there. In a way, yes, of course it was a fashion label, but it became a figure of speech as much as a T-shirt. It was shorthand for something, like Warhol’s Factory or Halston and the Halstonettes. BodyMap was a movement.