Kim Jones on taking Dior Men back to the future.

By Farid Chenoune

Photographs by Juergen Teller

Kim Jones on taking Dior Men back to the future.

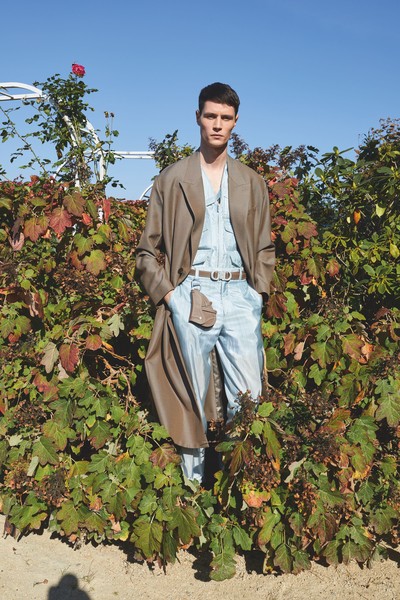

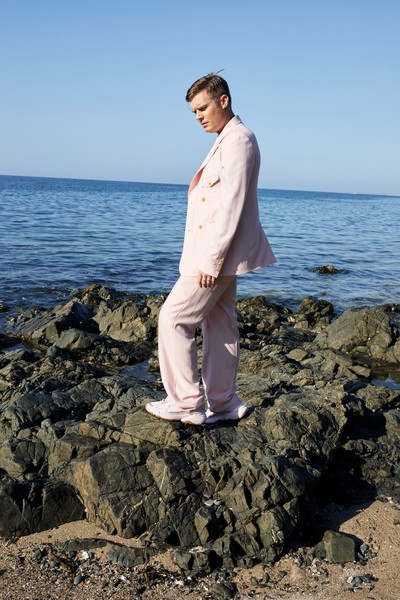

Kim Jones’ elegant and romantic debut collection for Dior Men was a vibrant statement of intent. By smartly exploring the idiosyncrasies of the house’s founder and using the couture savoir-faire that he put in place, it took Dior menswear back to the future, while adding just the right dose of Jones’s street-casual sparkle to make it defiantly of the now. By the end of the show, Dior Homme had been transfigured into Dior Men.

To understand more clearly how Kim Jones is building his new vision of now, System asked writer and menswear authority Farid Chenoune to visit the designer in his Paris atelier. Then, to re-examine the cultural and professional background that helped mould his view of fashion, Jones reconnected with Michael Kopelman, who as the founder of pioneering clothing importer Gimme Five is not only a British streetwear legend, but also the man who gave the Dior designer his first job nearly 20 years ago. Finally, Jones and his Dior ‘family’ flew with photographer Juergen Teller to Granville on the Normandy coast to spend an end-of-summer day roaming around Christian Dior’s childhood home. It was a welcome moment of calm for Jones, before his return to what he openly describes as ‘the difficult second collection’ – the next stage of his quest to make menswear modern couture.

‘I’ve looked at how Christian Dior

lived and what he loved.’

Kim Jones and Farid Chenoune

in conversation, October 10, 2018.

Last June, Kim Jones, the new artistic director at Dior Homme – rechristened Dior Men for the occasion – presented his much-anticipated first collection. His move to the house after seven years designing men’s ready-to-wear at Louis Vuitton was part of a more general game of musical chairs within the LVMH group: Kris van Assche moved from Dior Homme to Berluti where he replaced Haider Ackermann, while Off-White designer Virgil Abloh replaced Kim Jones at Vuitton.

Now aged 45, Kim Jones arrives at Dior with a reputation built over 20 years working in men’s fashion. His career began in 2001 with a final-year collection at Central Saint Martins praised by his mentor and teacher Louise Wilson and supported by his older peer Lee Alexander McQueen. He twice won the British Fashion Council Menswear Designer of the Year Award, once in 2006 for his own brand and again in 2009, for his work as artistic director at Dunhill. At Louis Vuitton, he redefined the house’s menswear, bringing in a more casual vision of modern luxury, which culminated in the spectacular 2017 Louis Vuitton x Supreme collaboration, which has been described as heralding a new era in the relationship between luxury and streetwear brands.

At Dior Men, Jones has designs on a new idea of masculine sophistication, one based in the savoir-faire of the house’s ateliers and its haute-couture heritage (he calls the latter a gold mine). Smart, amiable and insatiably curious, Kim Jones pulled himself away from the preparations for his second show (which he describes as ‘the hardest’) for a conversation in his Paris atelier that took in his way of seeing things, how he creates menswear, and, more generally, fashion itself.

Farid Chenoune: We’re here in your workspace, could you tell me about what’s around us?

Kim Jones: That’s our fitting room, where we usually sit and do all the work. We have the atelier downstairs and the team comes up to do the fittings. We do two collections, Spring/Summer and Autumn/Winter, without a pre-collection in between. We work to the commercial calendar, which is essential because we don’t only have our stores, we also have retail and wholesale. We also make lots of mini collections.

Your first collection for Dior went on show in June. How do you feel, looking back at the past few months working for this house?

I came to Dior from Vuitton, which is a very different thing. It is essentially a leather-goods brand, a luggage maker. I loved Vuitton and I still do, but it was a very different way of working. Everything was made in factories, outside of the building, so we didn’t have clothes or products with us all the time. Dior, on the other hand, is a couture house; it’s a ready-to-wear house. You can approach things in a different way. Here we have an atelier; tailoring is much more prominent here. We work in a much more creative way, and that’s the difference. Vuitton is a big, very well-oiled vehicle, but Dior has still got the couture aspect, which is something really amazing to work with as a designer. Then you bring your own interpretation of what the house is. The existing tailoring is successful so we’ll continue with that, because as a commercial person I think like that. But you don’t want to be doing something that previous designers have done. It has to be separate.

What steps do you take when you start work on a collection for Dior?

You know, obviously Hedi Slimane started this line, Hedi is now at Celine. Then Kris van Assche was the creative director before me, and Kris is now at Berluti. So when I came to Dior, I decided to go right back to the start: from Christian Dior’s childhood up until when he started the couture house. For me, that’s an interesting period. It’s also very personal. He loved nature; I love nature. There are elements I could relate to, and the archive is really fantastic, as I’m sure you know. There was a lot to see. The one thing that struck me, because I love art, is that Dior was a gallerist before he was a couturier and he had very interesting artists in his galleries. He was working with some of the most important artists of the time. So I looked at that aspect of his work, plus there are the relationships with the people I choose to work with and the world in terms of the digital age and social media. That’s something I find interesting, and I wonder what Christian Dior would be doing and looking at now if he were starting out.

‘I sometimes wonder what Christian Dior would be doing and looking at – on social media and in the digital world – if he were starting out now.’

Your first collection was full of lightness, with tulle and other sheer fabrics. It was quite a ‘garden palette’ – colourful, non- aggressive.

Yes, we were looking at essential couture. I like the idea of the romance of the house, and that’s what I was looking for in the palette. I wanted to see how you could take things from the archive that belonged to a person. I’ve looked at how Dior lived and what he loved, and that was really the essence of what we developed. For example, every dog that Dior had was called Bobby. We thought that was a sweet thing. A loyal companion. That’s when I started looking at the idea of working

with the artist KAWS, because he has this sculpture called BFF. The result was his floral statue in the middle of the set, which resembles Monsieur Dior and his dog. We thought that was a nice touch.

Essentially, you were looking at the life of a man called Christian Dior, not necessarily the codes of the brand.

I was looking at the codes as well, but I was predominantly looking at him, because he is still quite a mysterious character, in a way. He was a very private person. He had a loyal team around him, and I think that’s very interesting. I was looking at things that he liked in his youth, because essentially fashion now is quite young. I always look at the idea of dressing a man from 16 to 75. I like that aspect.

So you bypassed your predecessors and went back right to the beginning.

For me, it’s the most logical way to start. We still look at the commercial elements of the company that are successful – and I say ‘we’ because it’s a team – and then we look at what the newness

should be. Because the newness had to come from within Dior.

Instead of looking at Christian Dior as a womenswear couturier, you looked at the man himself. It is interesting that you approach the brand from that viewpoint.

I did look at what he did for women. Because what was considered very feminine in 1950 is something different in 2018. A fabric that was considered only for women could very well be acceptable for men to wear now.

How do you see the masculine/feminine legacy of Christian Dior?

I think it’s very relevant for now. He was looking at very masculine coats when he was doing womenswear, and I think you can apply those into the menswear quite easily without it looking feminine. It looks elegant, and I think that is important.

You have much experience designing men’s clothes, right from the very beginning of your career and your studies at Central Saint Martins.

I’ve worked on women’s clothes as well. I’ve done quite a few different things. I graduated from the Central Saint Martins Fashion MA in 2001. I’d started off doing graphics and photography, and I

didn’t like it, so I switched. I wanted to do something you could create a world around and clothing was the thing I was most interested in. Because you could work with photographers, you could

style things, you could art direct things. You could do everything.

There were two people in my life who have been really important in helping give me the confidence to do what I do. One was Louise Wilson, who was my tutor and very dear friend after leaving college, and the other person was Lee McQueen, who was like an older brother. I met him when I was 20. He was really one of the people I could talk to. He was very supportive of my work and liked the fact that I had my own eye and was interested in something different. He supported me, and I worked on one

of his labels. They were the two people who I could ask questions to, and who would be, like, ‘Just do it, don’t care’.

You also had a creative education from your family, right?

Yes, I came from a creative family, and I spent a lot of my childhood in Africa, which was amazing because I saw these incredible people, landscapes and wildlife. One thing when I saw these amazing tribespeople was what felt like their innate sense of style. It is one of my first memories, seeing the Masai people walking, wearing red and blue against a plain background. That was so powerful. It stuck with me. I moved back to London when I was about 14. My sister was leaving home and she gave me her fashion magazines – The Face and i-D and all that. I opened them and thought: ‘This is the world I want to be in.’ I was just always very interested in the way things looked. I am one of those people who looks at everything. I can really bore people because I love examining things just because they’re interesting. The thing about being a creative or a designer is that it’s your eye that casts the way the brand will look. Even though you are working within the codes of the brand.

‘Dior was looking at masculine coats when he was doing womenswear, and I think you can apply those back into the menswear without it looking feminine.’

To come back to Dior and men’s fashion, did you have a silhouette or a line in mind?

I want it to become fresher. I know Dior is very special to Mr. Arnault who owns the company, so I want to make him very proud of the brand, and I want it to become super-loved. That’s my goal. It’s one of the best houses in the world, so for me being able to do that is a real privilege and a joy. Dior

was a little bit more rigid before, and I want it to become a bit more relaxed and sensitive to the fabrication. To react to where we are in 2018 and how men dress. That’s completely evolved. But

when things evolve, they can also go back a bit. I’ve been working with stuff that’s very street-orientated, and that’s a very important part of menswear. But for Dior I want it to become more elegant. Elegance is the key thing for me. It’s chic, sophisticated, it’s modern. You can wear it in different ways.

One thing that’s extremely current is gender fluidity within design. How do you think about these things?

In the past, I’ve bought a women’s knitwear piece from Celine, because I liked it and it fitted me. I didn’t see it as a men’s or women’s garment – it was just a nice piece of knitwear. I have quite a few

womenswear pieces from when Margiela did Hermès that don’t have buttons on the front; they’re very easy wrap-around trenches and stuff. They’re from maybe 2001/2002. It’s always been that thing that women will wear men’s clothes, and some men will wear women’s clothes and it isn’t necessarily cross-dressing. We live in fashionable cities, so it’s specific to certain areas and I think once you get outside of that…

Can you give me an example?

If you look at a lot of rappers – who are very masculine – they now wear lots of women’s clothing in a very interesting way, which completely defeminizes it. Their influence on the way a younger generation is wearing clothes is very interesting. The styling is super cool. I love seeing someone I don’t know wearing clothes that I’ve designed. It’s the biggest thrill. And I love seeing how

they’ve styled them and how they want to wear them; they look really cool. That makes me happy. I don’t dictate. I’m not saying, ‘You should wear this head to toe’. I like the fact that people are mixing things up. It’s exciting. It’s like when you look at great stylists working with your clothing – it makes you think about what you do in a different way.

Do you also think that there has been a shift in what people actually buy? Now when you go into a luxury shop, the first thing you see is sneakers. It’s not ‘the bag’ any longer.

It’s sneakers and it’s jerseys, T-shirts, sunglasses. I think people look for comfort, especially in places like Asia where that’s very important. I go to every store and talk to people and I hear that comfort and style are the two things that a man needs. When you go to a shop, you touch something first to see if it’s soft and comfortable against your skin. I’m very boring sometimes, I’m very sensible and logical about how I work, because I am quite realistic in lots of ways.

Then you have the thing where you do the show and that’s the fancy part, but then you break it down into real items. Now I’m working with Dior, for the first time I could make couture pieces, like the beaded shirts with complicated couture detailing. We wanted to emulate the shine of the ceramics from Mr. Dior’s personal dinner service. They’re handmade but the feathers are lasercut. Each took nine weeks to make.

Do you know how the shops reacted, and if some looks were better received than others?

Everything was available to buy, and obviously some things are extremely expensive like the shirts, which are made to order. I think generally the collection sold very, very well. There are waiting lists for lots of things.

‘I’ve been working with stuff that’s very street-orientated; that’s an important part of menswear. But for Dior I want it to become more elegant.’

To come back to the suits and the asymmetrical looks, they were based on an illustration of this oblique line. But you are not an oblique person, you seem to be very…

I am not so oblique, but I think lots of people don’t really know me. I’m quite private, and I like lots of different things. Very modern things, but also very classic things. For example, I have a place in Paris that is very classically French and Parisian, and then I have a place in London that’s a brutalist building.

London remains a key part of who you are. When you mentioned Louise Wilson, I was reminded of all the things that I have heard about her. Why was she so charismatic?

Because she really believed in what she did, and because she really cared. That’s the thing. Some people would go through the MA and have the worst time of their lives, because Louise felt she couldn’t get out of them what they should be doing. She gave me a lot of self-belief. The last time I saw her was in Bali when we were on holiday, and she was telling me story after story of these

things that she shouldn’t have done to students. Her partner was like: ‘Oh god, you did worse than that, how about that one…’ We were laughing about it, because only Louise could get away with that. I think that was her charm. She respected people. She was one of those people who was so tough that

when she died it was a massive shock. I really cried a lot because I thought she’d never go away. She was so solid, she didn’t give a fuck. She instilled self-belief in people, and I think that’s the thing that’s important. She could also get extremely rude and throw things at people, slam doors in people’s faces, stuff like that…

She was demanding…

Yes, but if you can see that in someone and know how to handle that, you can deal with it. I’m very logical in the way I think. I like to have a schedule, and I like to get things done early. I’ve had the same right-hand, Lucy [Beeden], for 13 years, and she knows my process, so together we’re a really good team: organising, managing people, giving people respect. I will let people give me ideas, I will let people work how they want to work, as long as things are done on time. I think it’s really important to give designers freedom, because otherwise they get bored.

When I was talking of the London influence, I was also thinking about your experience at the end of the 1980s and the early 1990s, Saint Martins, the nightlife…

I think everybody in London went out every night, and it was just because it was social. It was how you would see your friends. We’d go out and socialize, all the designers together, then go home, go to sleep, get up, go to work.

I was reading one of your interviews the other day and you mentioned the Blitz Kids, who you spoke about with a kind of pride. One sentence in particular touched me: ‘They were so brave.’

That was the generation before me, and they were really brave, because they were going through bleak England in the 1980s. I imagine they must’ve been shouted at, beaten up, screamed at, but they didn’t care, they just wanted to be themselves. I think that paved the way for lots of other people to be themselves.

Were you like that?

No, I wasn’t. I was very shy when I was young. I never ever met someone and just decided, ‘I love that person, I want to be their friend’. I’m not like that. Everyone I have met in my life has been through an organic process. I think people who come to my shows come because they’re my friends. I think

that authenticity is interesting in this day and age. Because I think you have to be true to yourself. And obviously you work for a brand, but you work in the way you like to work, you bring in the people who you want to work: photographers, artists, models, musicians, actors. It’s very organic; it’s not forced. I don’t like things to be forced, otherwise I don’t think they work.

Do you have to struggle to keep it authentic? Because it’s not easy.

Yes, but here they have belief in me because they know that what I did at Vuitton worked, and Vuitton is a big machine. I think if you can work in that big machine for seven years and make it bigger and bigger, then you can certainly offer something here. Dior is the pinnacle for me, and it’s a really exciting thing to do. I work with Pietro [Beccari, Dior CEO] who I worked with at Vuitton, and I have a really amazing relationship with him. That gives me self-confidence – like Louise Wilson or Lee McQueen did.

‘A lot of rappers – who are obviously really masculine – now wear lots of women’s clothing in very interesting ways. It completely defeminizes it.’

In London you were close to people like Christopher Nemeth and Judy Blame. What remains with you about those people?

I was aware of Christopher Nemeth more through magazines. I only met him shortly before he died, because he lived in Tokyo. I met Judy Blame when I was very young, probably 16. He was such an impressive person, and someone who I became close to later in life. Sadly, he died earlier this year.

He was such a great, multi-talented artist.

Jewellery, styling – everything. We have been working on his book for a long time with the people at Michael Nash, and it’s changed and evolved quite a lot. The last weekend I had with him was really sad because he told me he was dying. He asked: ‘Please can you just make sure you finish the book.’ He was in a really good place in his life, very happy and content with what he was doing, and within a month he was gone.

The way that people like Judy dressed up, using all sorts of materials and fabrics – were you part of that, or were there two worlds? The world of what you do as a designer and what you wear as a person.

Back in the day, my friends and I would basically customize things to go out. We didn’t have any money, so we’d share each other’s clothes all the time. Something would be passed around and it would be changed a little bit by each person. Stuff like that. But as you get older, you get a uniform of things that you feel comfortable in. When I get to work I think about clothes all the time, so I don’t think about dressing myself up. I think about my job. But I have things for different occasions. I have

stuff that I love but wouldn’t necessarily wear. Sometimes I’ll just buy something because I really like the garment and think that it’s beautiful.

So you buy to collect, not to wear?

Yes. I have a very large archive of clothes. It’s an exceptionally rare archive, because it’s probably the only collection like it. It’s London street style from 1971 to about 1989 and it’s got Leigh Bowery, Rachel Auburn, Stephen Linard, Christopher Nemeth, Westwood.

For men and for women?

Yes, everything. This is something really interesting, for example. [Holds up shirt] It’s Adam Ant’s anarchy shirt. He loved this so much. This is probably from 1976. I bought it off his ex-wife. But I can show you more on my phone; I have my clothing collection on here…

How much does this collection inform your own work?

The clothes inspire me by the fact that they are beautiful. They’re not something that I look at directly. It’s a different thing. We look at old clothes, things with nice fabrics. When you look back

at clothes of the 1950s, fabric manufacturing was really good. When you work in luxury or couture, you have to appreciate these things.

How did you see luxury brands like Dior, Chanel or Yves Saint Laurent when you were starting out?

They were very relevant. I think that when people were forging or customizing a lot of things, like printing a fake Chanel T-shirt, it was this gateway into understanding the brands, because you’d recognize the monogram before you even knew what it really meant. I think it was that sort of thing. When we were at college, we had to go the library because we couldn’t afford to buy a password to Catwalking.com or First View to see the collections as they came out. Everybody wanted to see Helmut Lang at that time or Margiela. It was a different moment. Dior was probably the one that stood out because John Galliano was a Central Saint Martins graduate and he was making big waves. We were all fascinated by the spectacle.

Galliano was at Dior from 1996 to 2001, so you were still at school.

Yes, and it was so awe-inspiring. There were these grand spectacles and Dior looked like the most powerful house in the world. When I graduated John Galliano bought half my collection.

Was it a men’s collection?

Yes, and it was in an exhibition at a storecalled the Pineal Eye, which was the cool avant-garde store at the time in London. I went somewhere for a couple of days and came back and they said: ‘We sold it all.’ It was a mix of street, denim, and a lot of handmade pieces where I’d made the fabrics myself.

I would do schoolboy blazers but in a weird fucked-up way. Hand-knitted things and stuff. It was a lot of one-off pieces. I was quite upset that it got sold because I wanted to keep it.

‘My graduate collection combined street, denim, and handmade pieces, like weird fucked-up schoolboy blazers. John Galliano bought half that collection.’

Is there anything left of the spirit of those beginnings in your work today?

Fabrics. We can ask really amazing factories to make us a really beautiful fabric, and it’s just for us. And I think it’s really important, when people are spending at this price point, that they get a unique thing, and that the house is the only house that has that fabric or technique.

You’ve said you can’t stand the word ‘streetwear’ anymore.

I don’t think it’s relevant any longer because everyone wears clothes on the street. I think the difference between streetwear and fashion houses is the price point essentially. I think it’s all cross-pollinated now. Someone will wear something that’s a piece of streetwear with a piece of fashion, or

something that’s high street. People mix things up so much, I think it’s just style. I think style is the thing to look at.

Do you think that in terms of style women and men are now on the same level?

In certain places, yes. Like Tokyo, which is one of my favourite places. For me the Japanese designers are the thing… I mean, there was Lee, Helmut Lang, Margiela, Vivienne Westwood, lots of amazing designers, but I was really attracted to Japanese designers and particularly Jun Takahashi

from Undercover, because I met him when I was at college. I was working for Michael Kopelman, who had a company called Gimme Five. They imported Undercover, A Bathing Ape, Good Enough, all these labels that nobody else could get. Even Supreme, which back then was really small. I was very

lucky because Michael was a very generous guy and he’d always give us clothes, so I’d always have these things and people would be, like: ‘Where are they from?’ Back then, I thought those brands were so expensive because I didn’t have any money at all. They were really well designed. Every single bit of hardware was personalized. Most of them were made in Japan, and Japanese manufacturing is really interesting. When I had my own label we sold a lot to Japanese stores, and it

was cheap to make it in Japan and to export it from Japan to the US, in terms of taxes. You could get fabrics that you couldn’t get in Europe. We spent a lot of time there, and it’s a place I’m always really drawn to.

Why did you decide to stop your own company?

It was when I got offered the job at Dunhill. I had always wanted to be the creative director of a luxury-goods house. That was always my goal. I never wanted to do my own label; it was my friends

telling me to do it. I did a project for Louis Vuitton when I graduated, and then 10 years later I got that job at Vuitton. I saw the facilities that they had – I saw the grandness – and I was attracted. You know when you get a feeling, and it’s like, ‘I want to do that’. I am quite focused. I’m not a planner in life. Apart from my schedule, I just go with the flow, and I think that’s the most important thing to do. I always look at life in chapters. I had a really amazing time with my label. I travelled the world, I met loads of interesting people, but my goal was to work for a luxury-goods house and be the creative director. And they said: ‘You can only do the job if you stop the label.’ I stopped my label, and that money enabled me to buy a house, which I wouldn’t have been able to afford before. It was like growing up, I guess. I was doing menswear in London, and there wasn’t really anybody else doing that unless it was Paul Smith or Burberry. My first show in Paris cost me €150,000, and that’s a lot of money when you’re an independent designer. I thought that if I didn’t show in Paris, I wouldn’t be taken seriously.

Did you think that choosing to do menswear was more difficult than designing them for women? Were there fewer opportunities?

I did menswear because I wanted to make clothes for me and my friends. That was the initial thing. We couldn’t find the things that we wanted. Those things from Japan were incredibly inspiring. Menswear is more challenging to do, in a way. It’s more constricted. I don’t know why I decided to do it. I just did.

Do you like working within those parameters?

I like working for a house with a good archive. Dunhill, for example, has the most amazing archive. I think that’s the most interesting thing for me. It’s really important. At a label, you have the support, you have the team, you have great people to make something on a global level. I could easily relaunch my own label, but I’m done with it. I’ve issued my stuff for the 10th anniversary. When it’s your name, it’s always your name… I like to keep myself a bit in the background, I guess. To have a bit of privacy. When you see people who have been really successful, like Lee, it’s often really hard for them, because it’s their name. Anything would be upsetting if it’s a negative comment. I’m not that kind of person, but I can see what it did to people.

‘The term streetwear is no longer relevant; everyone wears clothes on the street. The difference between streetwear and fashion houses is the price point.’

A stupid question: traditionally couturiers used to have muses, icons, idols, real people. That type of thing is very rare in the masculine world. Who are your muses?

There are certain people I find very inspiring like Peter Beard, because he was a handsome guy who went out and did amazing things in the world. I’m fascinated by Warhol, by his world domination. Francis Bacon because he is interesting as a person, and was super crazy. We have a group of guys who have modelled with us for quite a long time, and they’ve become friends, so it’s easy to work with them. There’s four or five guys that we constantly have with us; their energy is very positive in the room and it helps when you’re doing fittings.

Are those guys you’ve always worked with? At Vuitton, too?

Yes, but then we’re also doing new casting here because it’s important to change things

Do you direct the way they walk and their gestures?

Yes. There’s Etienne Russo from villa eugénie who works on the show; he’s very precise in the way he talks with the guys. But sometimes you can see that a guy is a bit shy or that it’s his first time, so I walk next to them when we do the rehearsals to build them up and make them feel confident about doing it. We had Prince Nikolai of Denmark in the first show with the first look, because royalty is part of the history of Dior and because I’m half-Danish. I thought it was a nice thing to have as my first statement for Dior.

Speaking of collaborators, how do you work with Melanie Ward?

Melanie comes in to do the fittings with us. It’s a very easy way of working. I worked with her for my last show at Vuitton, and before that with Alister Mackie, who is still a really good friend of mine. What’s funny about Melanie is that she’s the stylist that all other stylists admire, because she is

really set in her ways. We actually laugh quite a lot, which I guess is quite rare in a lot of these houses. We take our work very seriously, but we take it with a certain lightness, and I think that’s a really nice way to work.

Does she bring new insights?

Yes. For example, when you’re working with very rich fabrics and you’re layering things up, sometimes it just helps to simplify things. I know what I want from the beginning to the end of a season, and sometimes you loop around and end up back at the start. From the start, I know how I want it to look.

We are doing the second collection now, and I think it’s more challenging than the first, because for the first one you go in running, but with the second you’re processing what’s happened with the first one, what was successful, in terms of figures, etc. I find the second one the most challenging. I still have the confidence to know that I can do it well. I’ve got confidence in my work because I’ve proved it critically and commercially. But even so, you have days where you’re, like: ‘What am I doing? Right,

that’s it, I’m just looking at the same fabrics again and again.’ Now I’m quite fast in terms of making decisions; I just think you have to be decisive.

Do you look at the pictures that get taken for campaigns and other parts of the business?

I look at everything. You have to. Consistency is the one thing I think people need to see when you’re starting at a brand and you’re making things work. You’ve got to have the message running across everything. The one thing Dior respects incredibly is the artistic vision of the creative director. I have to say that of all the houses I have ever seen, it’s probably the most respectful.

What about the jewellery?

I have Yoon working with me on that. She is somebody I’ve always wanted to work with, and I love her jewellery. There are two people who I admire, Matthew Williams, who did the buckles for us, and Yoon. And I would never want to copy somebody’s work; I just want them to come and work with

me. It’s nice to have that second opinion, it’s nice to have somebody come in from Tokyo and they’ve seen something cool. Jewellery is an important business now. Victoire is at Dior jewellery and I think she’s the most amazing woman in the world. I love her so much. I would love to do something with her as well; it’s about finding the right time to do something. What she creates is high jewellery. It’s a different thing.

Final question: there are very few black suits in the show. Is that a statement?

There are still black suits within the commercial collection and a lot of black things, but I wanted to have colour.

Is it a new chapter you want to write at Dior Men?

When I sat down with Mr. Arnault and Pietro, the two things that Mr. Arnault said were ‘colour’ and ‘fun’. You know, I work for somebody at the end of the day, and I respect what my bosses think. That’s important, too.

‘It’s been really hard for people like Lee [McQueen] who have been very successful. Because it’s their name. Any negative comment would be upsetting.’

‘It was like a secret society.’

Kim Jones and Michael Kopelman

in conversation, October 17, 2018.

By taking the craft and culture of Dior’s couture atelier and allying it to his specific vision of sharp wearability, Kim Jones revealed a desire to establish new codes for modern menswear. Fusing quality, comfort and attitude, it is a sartorial philosophy that’s partly grounded in Jones’ undying passion for ‘classic’ streetwear, the kind of hip, innovative clothing that he first came across 20 years ago while working at Michael Kopelman’s Londonbased distribution company Gimme Five. Kopelman – part of the International Stüssy Tribe, alongside the likes of James Jebbia (founder of Supreme), Hiroshi Fujiwara (future designer of Goodenough) and Luca Benini (impresario behind Italian streetwear enterprise Slam Jam) – opened Gimme Five in 1989 to import into the UK previously unavailable and unknown labels, many of them Japanese and American. It was these clothes, from such pioneers as Undercover, Visvim and Neighbourhood, that formed Jones’ mental fashion map and opened up new possibilities of how to combine his high-fashion training at Central Saint Martins with an altogether more street-based clothing culture. He still recalls with excitement the thrill of unpacking the boxes in Kopelman’s warehouse and examining each garment’s precise cut, intricate detailing and unerring attitude. With this in mind, System asked Kim Jones and Michael Kopelman – his first boss – to get on a call for a long-overdue catch-up. Together the pair reflected on the clubs and shops of London’s Soho, whether ‘streetwear’ is now a derogatory term, the enduring influence of mashing up Stüssy, Seditionaries and high-tops, the Wag Club, punk, Ron Hardy’s classic house, and dressing head-to-toe in A Bathing Ape.

Kim Jones: Let’s start with you. How did you start getting interested in clothing and how did Gimme Five begin?

Michael Kopelman: Well, I was always interested in clothing and into clubs and music. I spent the first pocket money I ever had on records.

Kim: I was the same.

Michael: My mother had an antique shop in Camden Passage and I used to go with her. I would go around the markets with my pocket money and got into buying army surplus stuff. You could have a real GI look and get those big army pants. I suppose that was around the time of punk, and you could also pick up lots of cool stuff around Portobello and Islington. You had to have the right gear to go out, so there was a real look that we wore to try and get into clubs. My sister worked at Fiorucci, and when I went to see her there I could see people going through a blue door down the street into a hairdresser called Smile. I went there with a copy of Pin Ups when I was about 13, in my school uniform, asking to get the same haircut as David Bowie, which I suppose was a pretty mad thing to do. I had left home when my parents went to live in New York, and was working in the City. I visited them there and my roommate James Lebon, who had also gone to live there, and over there you could hear all the hip-hop on WBLS. I saw Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s stuff and I saw fashion around me, not high fashion, what people around me were wearing. I was interested in doing something different. I was DJing at the Wag and there was a club called the Brain where people wore punk leathers, but also wore high-tops and TROOP jackets. Everyone was mixing everything together. Eventually, after going to New York and DJing there, I got asked by Stüssy to DJ for them in Japan. Stüssy was really hard to find here in London, so when I was made redundant from my job, I went to California and asked them if they wanted me to work for them in the UK. That’s how I started my company.

Kim: I remember one of the first things I saw that made me interested in fashion and music was when The Face did all of those double-page spreads on clubs in London like the Brain. That was my first inkling into that world, looking at it as an outsider, as a kid.

Michael: We bought all the magazines, i-D and The Face, and we looked at what people were wearing, particularly the people from the clubs that we knew. Magazines had a massive influence over what was popular. Not many people had those kinds of American things like goose jackets or high-tops or TROOP. It was only because we knew the people on the door of the clubs – because we’d been going for so long or DJing there – that they let us in.

Kim: Talking about Westwood and the punk thing – I find it weird when people talk about ‘streetwear’ because there was totally a fashion element to it. Westwood was involved and Malcolm McLaren was a great stylist in terms of how he made things look.

‘I went to Smile the hairdressers when I was 13, in my school uniform, asking to get the same haircut as Bowie, which was a pretty mad thing to do.’

Michael: I am really familiar with the term ‘streetwear’ – people have been using that term since the early 1990s, but it’s only really recently that it’s been

anything other than a derogatory term.

Kim: I don’t think it’s necessarily derogatory; I just don’t think people have known how to label what it is, because the quality and the make and the manufacturing and the thought processes have really developed over the years.

Michael: Back in the day, all those things had real meaning. Everything that you wore had a meaning and was connected to culture. Now it’s not connected to any culture. A mohair sweater with holes in it is ‘punk’. Or a skateboard T-shirt is ‘streetwear’. But it’s not. Anyone could be wearing that stuff. It doesn’t have any special meaning now; it is just another category.

Kim: You had such a defined look with everyone you hung out with. I remember the Stüssy Tribe and seeing and really admiring that look, and just thinking how amazing everyone looked.

Michael: When I had my shop, I went to Pineal Eye and I remember looking around and seeing the clothes that you’d made. I immediately understood that they were different from the other things there. I contacted you because I wanted to talk to you and I could kind of connect to you through what you were doing.

Kim: I remember music being very influential at Gimme Five because there would always be something playing in the stock room when we were packing boxes, tapes with Ron Hardy and Farley ‘Jackmaster’ Funk, and other stuff. That completely blew my mind and got me interested in that cultural side of things, because for me, music and clothing go hand in hand. I mean, I got really obsessed by Ron Hardy when I was at Gimme Five and I would be asking what track was playing and going to the record fairs each weekend to find the 12” of everything, because it wasn’t easy to get. And I started reading about the Music Box and the different styles of people who would go there. That was what inspired my collection at college that went into Pineal Eye, because there was that mix of punk and that preppy Ralph Lauren guy who went there. I loved the idea of everything being mashed together.

Michael: It was definitely an outsider culture.

Kim: You can still find that now in places like Cape Town, but it’s not particularly easy to find in big cities these days. I guess information is so much more freely available. Everything catches on much more quickly. I remember waiting for copies of i-D and The Face to come out so I could see what was going on and what people were wearing. Things were very limited. I remember being with you and unpacking boxes of stuff, like Undercover or A Bathing Ape, and just looking at all the details and thinking how amazingly thought out and super elevated things were. I remember when you would bring round the Undercover catalogue and we would look at it.

Michael: We had access to all of that stuff and were ordering it. It was like a secret society.

Kim: It was. And I remember you were always very generous and would let us order things. I’ve still got all that stuff because it was just so brilliant. It completely transformed the way I thought about clothes. I remember I always wanted to go and work for Levi’s in San Francisco after college – that was my dream. But then everything changed when I left college and evolved in a different way.

Michael: Well, it sounds like it worked out well!

Kim: [Laughs] I was talking to someone in the office the other day who was saying they used to dream of becoming the print designer at Top Shop, and we were like, ‘We’ve certainly gone a different way than we thought we would!’ That time in London was good, though. There was a lot of energy and diversity and integration and you would go to places and there would be so many different types of people. You would meet someone from a completely different background almost every time you went somewhere, which is partly why I love London so much.

Michael: I like living in the UK. Time has gone by really quickly since we started the company, and it’s interesting to see the progression of all the brands and how big it has all got, because it wasn’t like that when we started. And there weren’t that many famous DJs and there wasn’t a big culture behind it. The brands that we worked with just weren’t big.

Kim: Yet all those Japanese brands that you pioneered and brought into the UK have gone on to become so influential.

Michael: I am really happy for them all. It was always the case that I would find stuff and get really excited about it and then really struggle to persuade anyone that it was any good. That was how I opened Hit and Run, and the Hideout. But what we were doing just wasn’t popular. Supreme was always popular; the other things just weren’t. There was just a small niche of people who were into it. Even with sneakers. When we turned the Hideout into a pop-up shop and had all of these special sneakers from Nike, we had them because people weren’t really interested in them. And opening Foot Patrol was very difficult. It wasn’t a popular shop, and now when you look at how big everything is,

it’s really unbelievable. It just got bigger and bigger and bigger.

‘People have been using the term streetwear since the early 1990s, but it’s only recently that it’s been considered anything other than derogatory.’

Kim: With Fraser Cooke at Hit and Run, I’d help fold the T-shirts and sweep the floor and stuff, but we were obsessed by the clothes there. It had a real cult following, and other people didn’t know about it, which was partly why we loved it so much. It was kind of like a club. When you saw someone else wearing it, you knew they knew it. Everyone would be freaking out when they saw someone wearing it walking down the street in Soho. I found loads of funny pictures of us sitting in Golden Square, and I was dressed head-to-toe in A Bathing Ape. People just wouldn’t have known what that was back then.

Michael: Yes, we were really into that. It’s nice to see that people like it now. It’s amazing how long it takes to spread.

Kim: It was like a very slow burn that then went really fast. I remember you built a sense of community around the brands and the people who worked at Gimme Five, and it was a very family feel. You created a fun environment where people would look forward to coming in to work. You taught me a lot about how to work with people and how to treat people in the office. That was something I picked up from a very early point.

Michael: Well, thank you – it’s obviously stood you in good stead!

Kim: I work with Fraser quite a lot because of the Nike collaboration and we really enjoy our Dad-joke sessions, laughing over Viz captions. I think it’s quite a rare way of working, but it is a very successful one. Marc Jacobs works in a similar way. I was talking to Jony Ive at Apple about it the other day and he was saying it’s about having a team that you are close to. You’re with them all the time, so you have to enjoy the process. That is absolutely true. Another thing you taught me was how, when Hiroshi and then Nigo were over and came into Gimme Five, you would always introduce everyone to everyone. Did you meet Hiroshi through Stüssy when you went to DJ or was it before that?

Michael: Actually, I was DJing in London and we knew some guys from Bristol and one of the people that we really looked up to was a DJ called Mil’o who had some records on the Major Force label. I was in Camden Market and saw this guy walk past in a Major Force jacket and I was, like, ‘Oi! Come here!’ And I grabbed him and it turned out to be Hiroshi. I asked him where he got the jacket from, and then it turned out that we had some friends in common. And then, when I went to Japan, just by chance Hiroshi and I were DJing together in this kind of superclub. He is a great DJ with really good taste in music, and I asked him to take me to Major Force, because I wanted to get more records. It was very hard to get all the promos. Back in London, I went to a shop called Bluebird Records where they sold lots of imports and I swapped some of them for US promos. There

was like a 12-year-old in the shop who was up for doing some bargaining – he turned out to be James Lavelle.

Kim: That’s crazy!

Michael: I know! I like to think that is how James Lavelle first got his hands on Major Force records and how he had the ambition to do Mo’Wax.

Kim: There was a real synergy to that time. It was an interesting organic process. There wasn’t a thing where people network like they do now. Everything that has happened to me has happened in a very organic way. I never planned anything, I just go with the flow. I think that at that time, things just happened, which made things exciting. There was

real scope for possibilities.

Michael: When I worked in the City, I knew that there was good music in Tokyo and I went there on business. I went out there by myself looking for acts like the guys from Major Force. Looking back, it’s so funny because I would finish my job and do all my duties and then go out all night looking for this stuff. And there was just so much gear and so much info to soak up and you couldn’t really get it from anywhere else. I remember buying these Levi’s jeans that were in a box and bringing them back to England, and people were asking me, like, ‘What is that?’

‘I’d help fold the T-shirts and sweep the floor, but we were obsessed by the clothes there. It had a real cult following, that other people didn’t know about.’

Kim: That was the anniversary jean?

Michael: They’d bought the original looms for the jeans and set them up and remade jeans that they’d then put in a box. I just used to come back with all this stuff. It was really, really good fun. I wanted to go to Akihabara to buy all this stuff and when I got there, I just couldn’t believe all the Seditionaries reproductions, and all these records that were really rare and difficult to get hold of here. It was all there. It was an exciting place, full of cult-y stuff.

Kim: It is probably where I do most of my shopping. There is so much to see and I love just looking at everyone in the street. The second time I went to Japan I just completely fell in love and I have been going back constantly. I could live there at some point. I do love it.

Michael: I’ve kind of calmed down now, [laughs] but back in the early Gimme Five days, we used to get a lot of stuff from over there, and we used to send a lot of stuff there, too. We worked with Judy Blame, had a distributor and made our own products; it was really exciting. When I moved out of home, I moved into Great Portland Street and met James and Mark Lebon and I remember going to their place in New Cavendish Street and meeting Judy and Ray Petri. All of those guys had been to Japan and had a big influence over my taste. Mark was working with Judy and Christopher Nemeth. It was a really amazing time.

Kim: And all the work that happened then is all still so relevant. I mean, it is referenced non-stop. Let’s talk about Judy. He was amazing because he looked at everything in every single way. He made high and low, and whatever you want to call it. He basically mixed everything up in a really great way. I think a lot of people don’t actually realize that he did it, either.

Michael: What a great guy; I miss him a lot. I didn’t really appreciate how fantastic he was when I first worked with him, although we had a really big output. We were just trying to pay the bills and make work together. Now when I look back I really see how amazing he was. I really believe in all of the statements that he was making.

Kim: I came in at the tail end of it all, seeing the things that he’d done without realizing that it was actually him. It goes back to that cultural aspect of work, which for me now is one thing that I try to do because it’s the most relevant way to get people to connect to what we do. I think it’s also how we live our lives – the cultural side is everything. The music, the fashion, the people. That’s one of the things that I learned early on from you and from meeting Judy and all these different people, like André Walker.

Michael: You can’t go to the Wag Club and see Leigh Bowery in the bathroom any more. It’s very hard to discover all this stuff. I see people picking up on it all now, and that’s great. But Judy – I feel very privileged that I could meet him, see him in action and be friends with him. I feel the same about Mark Lebon and all the people I know who are still standing from that time.

Kim: I like to see the next generation of people making an impact on the world in a creative way, too.

Michael: I’m into the same things I’ve been into since I started working, so whether it is vintage stuff, technical stuff or utility stuff, that is what I like. I never really go outside that comfort zone. The music is very important to me and I am always looking for new and old music. I look at all the sites and at what people do. But the people I have a connection with are the most satisfying to watch and follow.

Kim: I think I like all the same things, too, but obviously when I work for different places, I look at their archives as well. I still love all the same stuff, it’s just gone in a different way. There are things I dreamed about and I have done them, and I still love all the things I’ve always loved. It just evolves.

Michael: I don’t know how you get your head around doing what you do. Congratulations for managing to do it!

Kim: I’m still figuring it out myself! Thanks, Michael.