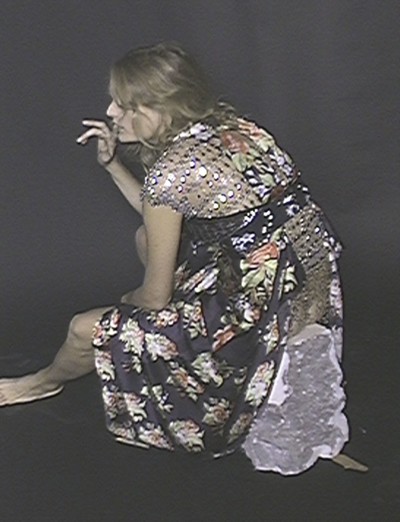

Designer Julien Dossena and art director Marc Ascoli discuss their ‘reanimation’ of Paco Rabanne.

By Marta Represa

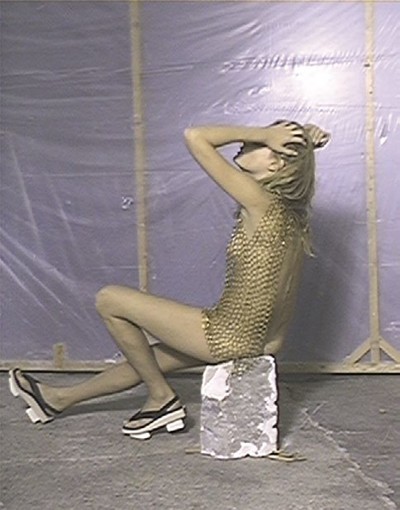

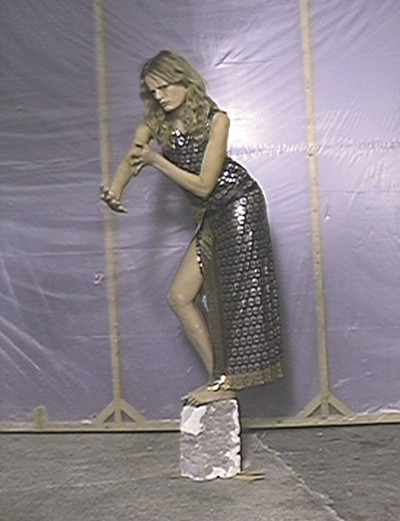

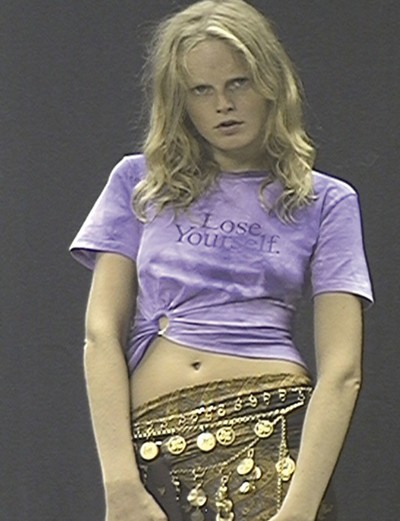

Photographs by Sharna Osborne

Styling by Francesca Burns

Designer Julien Dossena and art director Marc Ascoli discuss their ‘reanimation’ of Paco Rabanne.

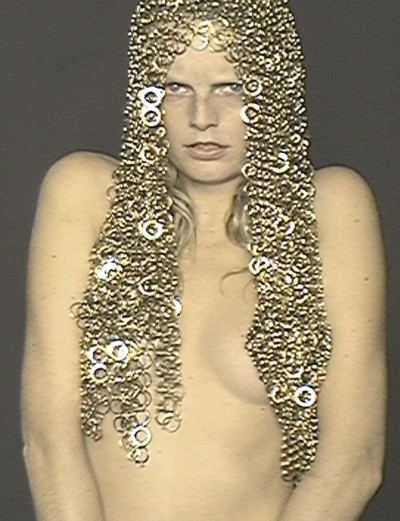

For over 30 years Paco Rabanne meant pizzazz. It meant sexy. It meant creativity. But by 2013, when French designer Julien Dossena arrived at the house, Paco Rabanne needed bringing back to life. His reanimation strategy – surprising to some – was not to attempt to out-Paco Paco or go wild with the archives, but rather to return to the heart of the house’s mission with the question: what can Paco Rabanne bring to modern femininity? From there, and a beginning with a newly introduced line of underwear, Dossena has set about quietly rebuilding the brand from the ground up, repositioning it, without removing its soul, trademark touches and poised panache. This sensitive refashioning of the Paco Rabanne woman has been growing in confidence with each collection and reached a wonderful crescendo in Dossena’s highly praised Spring/Summer 2019 collection. All beautifully made chic bohemian layering and eye-popping patterns, it presented, for example, the house’s classic shimmering chain mail updated, softened, printed and brilliantly blended into tops and skirts.

Alongside Dossena throughout the process has been legendary art director Marc Ascoli, bringing the expertise and experience amassed over a long career creating some of fashion’s most unforgettable images for the likes of Yohji Yamamoto, Jil Sander and Martine Sitbon. Julien and Marc sat down with System to discuss how the Paco Rabanne woman is always evolving, Françoise Hardy’s 25-kilogramme dresses, and how fashion is as much about observing as making.

Marta Represa: Let’s start by talking about how you first met and began working together.

Julien Dossena: I had the idea of working with Marc almost right away. Paco Rabanne is such a unique brand in the Parisian landscape – for the clothing, of course, but especially in the way Paco viewed femininity – that from the beginning I found myself thinking of Marc’s images for Yohji Yamamoto and Jil Sander. There were two pictures in particular I couldn’t let go of: Amber Valletta in a black dress having her makeup removed by two hands, and Amber Valletta against a flaming red background wearing a camel coat. They were exactly my idea of beauty, of something extremely refined, which fitted in perfectly with my concept of the Paco aesthetic. Back then, we hadn’t

met yet though.

Marc Ascoli: True, but I did know your work. Marie-Amélie Sauvé had asked me to come see one of your first shows, and I was immediately intrigued. Actually, now that I think about it, I had already seen one of your collections before she mentioned you.

Julien: You were at my second show.

Marc: It was the one in the small room at the École des Beaux-Arts. And for the record, I immediately felt that you wanted to be both extremely simple and really radical, yet at the same time you were so clearly on a quest for beauty. And not just any kind of beauty, but a renegade, androgynous one, where shoes were the most important part of the silhouette and soft fabrics clashed with chunky ones. It felt compelling right away, like you were creating a cool sense of femininity for the product, but also creating very distinct characters. Your women were timeless, elegant and serene, but they also showed a streak of rebellion. I liked that.

Julien: My very first concern when I started back in 2013 was how I would express femininity through my clothes, even before I began delving into the house’s archives. I wanted the Paco Rabanne woman to be strong, militant, active, liberated from any sort of cuteness or coyness. We’ve been working from there ever since, really.

‘When I started in 2013, I immediately wanted the Paco Rabanne woman to be strong, militant, active, liberated from any sort of cuteness or coyness.’

What has been the best part of working together over the past five years?

Julien: More than anything else, it’s been about doing the research and progressively becoming more and more precise with our vision for the brand. Finding the right balance between the house’s heritage, our clients’ needs, and fulfilling our own creative vision is a never-ending job, but that’s what I enjoy the most about it.

Marc: Plus, in our work, it’s all about creation, never about destruction. And especially about creating a relationship with the women we dress. Never by putting them on a pedestal, but by sparking a real dialogue with them, getting to know them intimately so we can find common ground and an intellectual and emotional affinity. That’s how you really get to understand the evolution.

Julien: Absolutely. Observing women is a constant for me. Which is strange in a way, because I grew up thinking I wasn’t any different from them. As a kid, I actually felt closer to them than to boys. It wasn’t until we were all teenagers and my friends started getting their first boyfriends that I noticed the difference. That’s when I started observing and finding out how I could contribute to their lives. At the end of the day, that’s what ties together all our creative vision and our team effort. And, of course, there is a lot of hard work and organization behind it all.

Marc: Sometimes spontaneity creates interesting results, but as a general rule each project needs a lot of preparation. Our jobs, contrary to what some people might think, are not about showing up with our hands in our pockets and smoking cigarettes on set. They require an enormous amount of research and analysis, even more so nowadays, considering the amount of information we have access to.

Has that changed the way you work?

Marc: Yes, and I actually think it has made the industry more interesting in a lot of ways. Of course, there are some things I find outrageous, particularly the idea that anything goes. I call it the ‘whatever style’: when you are discussing the clothes’ technical details and people answer ‘whatever’, before changing the subject and talking about the latest exhibition in town. That is not how you achieve quality. True, fashion designers are no longer just clothing suppliers as they were in the 1950s; there is now a real industry, which creates global interest. But that doesn’t mean that we can ever forget the idea that what we are making, primarily, is clothes. That should be our priority.

Julien: Fashion has become a pop-culture staple over the past few decades, while at the same time paradoxically acquiring a purely cultural patina. Shows look more and more like pop concerts, and yet clothing has never been more closely analysed and intellectualized. But, when all is said and done, designing is what really occupies 90 percent of our time, which is why you won’t find many people with families or in long-term relationships in the industry. And regarding what you were just saying, Marc, it took me a while to grow out of that ‘whatever style’ and realize that fashion was far from frivolous. But I think that idea has a lot to do with the patriarchy, and its dismissal of fashion as ‘girly’. It has begun to change with women taking control of more aspects of the industry.

Marc: There is also so much more money in it now.

Julien: Which of course is also interesting to straight men!

Marc: When I started working, €200 million in turnover was beyond anyone’s expectations. Today, it’s a midrange performance for a mid-sized company.

Julien: And it concerns us creatives, too. We used to be appointed because of the style and identity we could bring to a brand. Now, one requirement when you’re hired is guaranteeing a large turnover.

‘The best career advice I was ever given came from Nicolas Ghesquière when we were working at Balenciaga, and it was, quite simply, ‘last’.’

Designers are now often under tremendous pressure to turn brands into giant moneymaking machines in fewer than three seasons or risk being fired. That doesn’t seem to be the philosophy here.

Marc: Designers are long-distance runners, not sprinters. As a brand, you need to give it time if you really want to create a feeling of connection with the public. Frankly, if a designer already feels under pressure before his second show, I can guarantee that show will fail. The horizon needs to be wider than simply fast money, otherwise designers will – and do – suffocate, no matter how talented they are.

Julien: I was lucky enough to land at a brand where fashion had been nonexistent for decades, where I was able to build everything from scratch in order to create what I imagined a modern Parisian house should look like. That allowed me to take my time and choose a team that truly shared my principles. And it’s funny how things evolve almost without you noticing, because, looking back, I remember having a very precise, sharp idea of the Paco Rabanne woman as being extremely athletic, which was in tune with the times a few years ago. That’s why one of the first things we came up with was the sporty underwear with a logo, what we called Bodyline, which quickly accounted for 20 percent of our turnover. Which, in turn, bought us two years to experiment and evolve towards what the brand is now. Economically building a brand is a journey, and always a bumpy one, so a solid foundation is essential rather than relying on random collections or being the industry’s new darling. Because at the beginning, we are all the new darling, regardless of our style. And in 80 percent of the cases, it ends badly. The best career advice I was ever given came from Nicolas Ghesquière when we were at Balenciaga, and it was, quite simply, ‘last’. It was very much on my mind when talks with Puig started, and I think we have been on the same page since.

Marc: As an art director who has worked closely with designers for decades, I can tell you my job depends enormously on understanding their creative vision for the brand. Which inevitably requires time and reflection on their part, too, mixed with endless curiosity and a will to surrender to reality and to catch the zeitgeist.

It’s quite the balancing act, isn’t it?

Julien: Definitely. We often talk about a designer’s creative evolution, but we forget to mention the public changes, too. It’s a designer’s responsibility to stay in tune with his or her audience and to change according to it. It’s a permanent conversation, and your audience needs to be ready for anything you present them.

Marc: To me, great fashion is the selfevident relationship between personality, talent and timing.

Julien: Yes, otherwise you run the risk of creating something completely unsuited to its time, as awesome as it might be. And even if, by chance, it clicks, it’s like a one-night stand, whereas you need to build a relationship.

Does that mean you knew how the brand would evolve from the start?

Julien: Not in a Machiavellian way, but yes. I knew that the first thing was to catch the eye of a clientele that would understand the brand, and then to take it on a journey. Everyone, particularly in English-speaking countries, had a very precise idea of what Paco Rabanne was, the disco metal-mesh dresses, ‘wacko Paco’, and all that. But there was so much more to him: his love of all things esoteric, his incredibly democratic spirit…

Speaking of which, the pricing in your collections seems extremely eclectic. Is that another nod to Paco’s heritage?

Julien: Exactly. When I talk about him being democratic, I’m talking about his DIY paper wedding dresses sold with French Elle back in the 1960s. I wanted the brand to remain accessible to anyone entering the shop, whether it’s a 15-year-old with pocket money buying a yoga bra or a 50-something CEO or artist looking for a coat. Our price range can go from two figures to €10,000 for a metal-mesh dress encompassing all the savoir-faire of the house. But that mesh dress is just one aspect of the business, because once you have one, that’s it, you’ll never buy another one. I find the mix of styles and the idea of comfort much more interesting than cocktail dresses. Which is why in my last show you can see looks combining, for example, a €490 bias-cut skirt with a €170 T-shirt and a €7,000 piece of body jewellery.

Marc: Each garment has its price. I’ve never understood the whole €350 for a T-shirt thing.

Julien: I just don’t find that modern. If creating a brand is today a global endeavour going well beyond the clothes, you need to be inclusive. And speaking pragmatically, I wanted to lure in the sort of clients who would never otherwise set foot in the shop.

That’s also where the image-making comes in…

Marc: Voilà. It’s about creating a very recognizable aesthetic with which the viewer feels comfortable. No striking, bombastic statements or punchlines here. Just an artistic still life, sometimes also inhabited by characters, and a laser-focused colour palette. Something the public would like to be part of.

Julien: It’s a fantasized reality, but a reality nonetheless.

Marc: Otherwise nostalgia kicks in, and that’s the danger for a heritage house like Paco Rabanne.

‘These days, fashion shows look more and more like pop concerts, and yet clothing has never been more closely analysed and intellectualized.’

How do you work together?

Julien: Like everything else, it has been a long-term project for us. I think on our first meeting we discussed what the brand meant to each one of us, and I talked Marc through my creative vision,

the product and the woman I wanted to reach, while of course, taking the industry as a whole into consideration. That was when we decided that shooting models was not necessarily a must, and

we really wanted to evoke the idea of a certain woman.

Marc: It was not just a woman; it was also a character with her own life. As viewers, we observe who she is through how she lies on a sofa or the way she puts her shoes on the floor. The idea being always that this woman is not just some fantasy. She really exists, which opens the door to an intimate relationship between the viewer and our work. To get to that, we usually start by each working on a moodboard, then comparing and adjusting them, and choosing the rest of the team. Above all, we strive to be coherent with what we’ve previously created, and to achieve a certain balance between spontaneity and, even if this word seems to be banished from fashion nowadays, finesse. Not everything in the world is about cool. Refinement matters, too, more and more lately. We’ve kind of overdosed on streetwear.

Julien: We’ll never entirely agree on that one. [Laughs] I still think you can work on streetwear, but it needs to be elevated. It needs to be an inspiration, not the be-all and end-all. Again, it’s all in the equilibrium between reality and fantasy.

Marc: And the whole team also plays a crucial role in that. I can’t stress how important Marie-Amélie is in our projects. Her career and her vision have been defining for us all. And, of course, Paris. Working on one of the biggest avenues in the world for luxury, where customers and the industry expect collections of the highest level, is a real privilege. And it’s something I always remember while working. In that aspect, there’s nothing casual in my work.

Julien: True, we all understood the potential of the name Paco Rabanne the minute we got here.

Attached to the name is a very particular idea of femininity, and what Parisian women stand for.

Julien: I think it’s quite old fashioned to contemplate a woman as a sort of fictional figure. Personally, I have never fantasized about women like that. I’ve been fascinated by real Parisian women, though – creative, hard-working and full of character – and I continue to try to give them the tools they need to be more… I hesitate to use the word ‘comfortable’, because it means such different things. Some women find comfort in a corseted, armour-like silhouette; others in oversized proportions and soft fabrics. To me, comfort is anything that visually gives the impression of a strong, independent woman, while expressing the sensitivity that, to me, is the real strength of the feminine.

How has Paco Rabanne changed through the decades?

Julien: What I’ve always found most compelling about Paco is how he gave women the chance to reclaim their bodies. His goal was to make them happy, but he did it in different ways during his career. There was an evolution that started with the idea of Amazons, all-conquering females who filled the whole room.

Marc: It was the era for it, too. His competitors were Saint Laurent, Courrèges, Cardin, all with very different ideas of womanhood. I think he was reacting to the Parisian couture landscape of the time by designing all those suits of armour.

Julien: Which could weigh as much as 25 kilogrammes.

Marc: Françoise Hardy remembers having to be carried off the stage after her concerts because she couldn’t even move under the weight of those dresses!

Julien: It might sound strange to say that he was respecting women while putting them through that, but he was offering them a brand-new sensuality, completely outside the established forms in the Parisian landscape and beyond.

Marc: He was also very inclusive.

Julien: Exactly, he was one of the first designers to put a black model on the runway.

Marc: It was not so much about Paco Rabanne’s clothes as it was about Paco Rabanne’s universe.

Julien: As a matter of fact, I’m not even sure that fashion in and of itself was his priority. I think he used it as a means to express a new, androgynous kind of femininity. And that’s what I’m going for, too.

‘Designing occupies 90 percent of our time, which is why you won’t find many people with families or in long-term relationships in the industry.’

That androgyny, along with diversity, was particularly self-evident in the casting of the Spring/Summer 2019 show.

Julien: I’ve always really insisted on those two things for the casting for the reasons we’ve just mentioned, but also because I like to imagine a whole character to go with each one of the show looks. Which also explains why each model has different hair and make-up. I don’t know if you remember those ‘clone shows’ where all the girls looked exactly the same?

Marc: All with the same little Alice bands and the same ballerina chignons, yes! So 2000s.

Julien: It’s important to find the look that best suits each girl’s body type. Add to that the model’s attitude and personality, and you get a true narrative going for the show.

Marc: Not to forget the lighting; I loved all those orange lightbulbs.

Julien: They were supposed to mimic a neon-lit street in an Asian megalopolis, but they also had a sort of modern Moroccan design edge to them. They made the room warm in any case.

Marc: A certain pop star warned me about them before I entered the venue: ‘Darling, it’s too hot in there!’ Thank God it wasn’t winter, so the fur coats were nowhere to be seen. But yes, the set was good. So was the Serge Gainsbourg soundtrack.

Julien: I love how the music can help convey an aesthetic message.

Speaking of which, there was a clear mystical message in that last show. And as you said, we all know the Paco metal-mesh dress, but the esoteric, spiritual, almost hippyish Paco talking about his past lives and the end of the world is a lot less well-known outside of France.

Julien: True, and that aspect of Paco Rabanne was very much on my mind throughout the whole season. And I mean that in more ways than merely the visual one. His mysticism is clearly important to him, to the point that he has now dedicated his whole existence to it. It was always expressed through his work in different ways. He was the first fashion designer to explore that sense of spirituality through fashion and, in a way, his women were priestesses. In a nutshell, it was something I had wanted to do for quite a few seasons, and the timing was finally right to introduce that lesser-known Paco to the audience.

It worked – the show was included in all the season’s best-show lists.

Marc: It was? I think that calls for a toast. Time to open some Champagne!

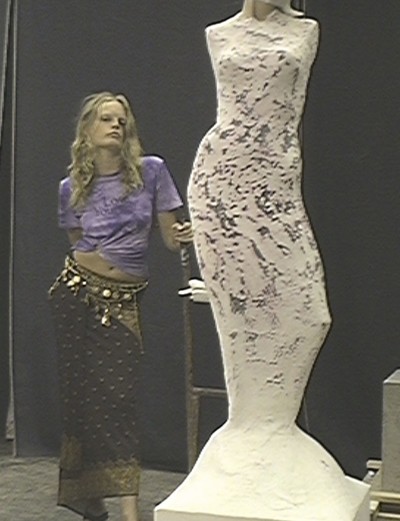

Talent: Hanne Gaby Odiele.

Photographer’s assistants: Jodie Herbage, Milly Cope.

Stylist’s assistants: Bianca Raggi, Emma Simmonds.

Make-up artist: Niamh Quinn.

Make-up assistant: Libby James.

Hair stylist: Gary Gill.

Hair assistant: Tom Wright.

Nail artist: Pebbles Aikens.

Production: 360PM.

Casting: Barbara Nicoli and Leila Ananna. Photography in the London studio of Daniel Silver, represented by Frith Street Gallery.