Long before there was ‘diversity’, ‘community’ or ‘non-binary’, there was Telfar Clemens.

By Hans Ulrich Obrist

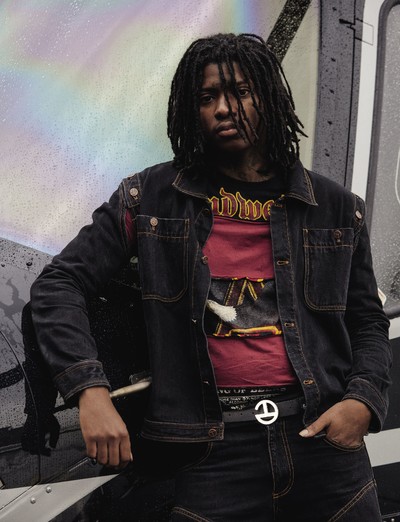

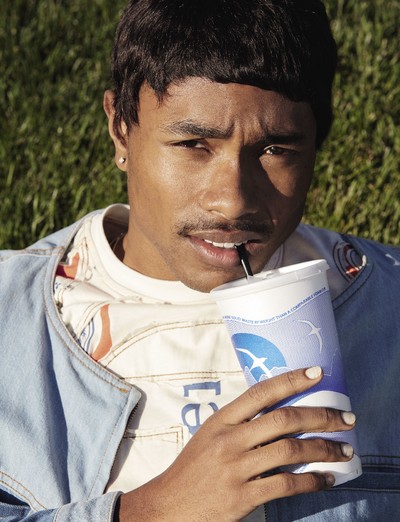

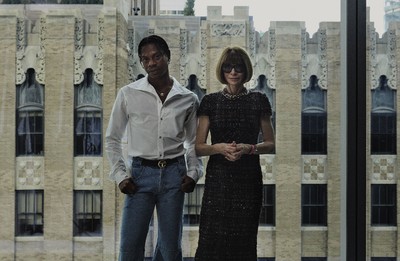

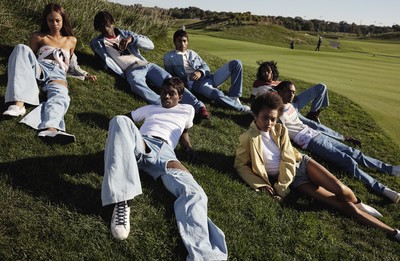

Photographs by Roe Ethridge

Styling by Avena Gallagher

Creative direction by Babak Radboy

Long before there was ‘diversity’, ‘community’ or ‘non-binary’, there was Telfar Clemens.

Back in 2005, long before ‘diversity’, ‘community’ or ‘non-binary’ were buzzwords and three years before the United States had elected its first black president, a young man named Telfar Clemens founded a label to make non-racial, non-gendered fashion. For over a decade, he produced his original, unique and groundbreaking clothing of repurposed classics and twisted basics, and for over a decade, much of the fashion press – System included – simply ignored him. In 2017, Telfar won the Vogue/CFDA Fashion Fund and they (we) had to take notice. Today, after years of running his own show at his own pace, the rest of the world has caught up with Telfar Clemens and his ‘horizontal, democratic, universal’ fashion.

Because Telfar really is its own thing, a label that effortlessly crosses the borders between art and fashion, while creating both. It is the vision of a designer who believes in collaboration, in working together with a constant group of creative friends and acquaintances, people like designer Shayne Oliver, artists Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch, and, perhaps most importantly, Babak Radboy, now the label’s creative director.

Since Clemens and Radboy began working together, they have been refining and redefining Telfar’s position and image, building a real business through thrilling clothes, unexpected initiatives and pioneering collaborations. They’ve worked with big-box retailer Kmart; they’ve redesigned and produced the uniforms for US fastfood chain White Castle; and they’ve brought art and fashion together in seasonal presentations at venues including White Box, the New Museum and London’s Serpentine Gallery. Their latest initiative, the Telfar World Tour is fashion presentation as concert, a touring show featuring the clothes on muses, singers and models. Held off-season and sometimes off the fashion grid, the concerts are symbols of the brand’s attempts to reach new audiences and live up to its slogan: ‘It’s not for you – it’s for everyone.’

The unisex clothes themselves are both quietly radical and deeply American. A child of the 1990s, Clemens grew up with labels such as Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren and their signifier-only, idealized vision of what it meant to be and dress ‘American’. That WASPy, exclusively inclusive casual elegance was then reappropriated and transformed into something entirely different by black America. Clemens has taken both these oddly intertwining inheritances and appropriated them differently again as part of an ambition to become the era-defining version of 21st-century American fashion, to create something that is uniquely him and absolutely now.

This summer, the Serpentine Gallery’s Artistic Director Hans Ulrich Obrist sat down with Telfar Clemens and Babak Radboy in New York to discuss where it all began, how the brand manages to operate both inside and outside the system, and why the Telfar brand really isn’t inclusive.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Can you tell me about how Telfar started back in 2005? What kind of clothes did you make in the very beginning?

Telfar Clemens: Basically, I’d buy three T-shirts from Orchard Street and I would put them together in a way that meant you could wear three T-shirts at once. Those were the first pieces.

So three people could wear it?

Telfar: It was one T-shirt, but two people could wear it at the same time and in different ways. At that time the big white T-shirt trend was in, and everyone was wearing oversized T-shirts. Mine was a bit like that, but a little inverted. So, it still looked as though you were part of that crew. But then it was like, Wait, why does yours have the sleeve all the way over there, and there’s a hole here? That was the first thing I was making, and I realized people were buying it, and I was selling out. That’s when I started selling through Vice magazine. They had a store and a friend of mine worked there. They would always have these cool parties – Vice was still cool at that time – and they were the first to invest in the line. They gave me the first show I did, and I dressed the entire House of Ninja.

In which year did the first show take place?

Telfar: This was in 2004, when we did the Vice Is Burning show.

‘Basically, I’d buy three T-shirts from Orchard Street and I would put them together in a way that meant you could wear three T-shirts at once.’

Before we talk about the shows, tell me who your hero and heroine designers were.

Telfar: The designers who made me want to switch a tag? I would get a lot of Vivienne Westwood. I would go to the European women’s designers section at Century 21 and just look through literally everything. I would look at the seams, anything that looked cool, things I didn’t understand. I was able to get stuff for one night and then I’d return it the next day and get something else. I would get a lot of Comme des Garçons and at that time, Helmut Lang was… well, that was what you went to Century 21 for. There were things I wanted to make or that I aspired to make, and there were things that didn’t exist for me. I got to experience both through shopping.

The Vice Is Burning show was in 2004?

Telfar: It was a riff on the movie Paris Is Burning that Vice was doing. It wasn’t a solo show, but after that, I got different opportunities to do new things. The best thing that came out of it was that I developed a friendship with Willi Ninja, who at that time was running a modelling agency. He was just driving around in a minivan with all these models in the back; he was sweet and cool and liked my clothes. Then shortly after the show he died. That show was the beginning. After that I really got a lot of opportunities to show my work through the art world.

More and more architects and designers are finding a way in through the art world, because it is so open.

Telfar: It’s like a vector in other directions. People appreciated the stuff that I was doing. We had a good community of people who also had resources, and it was like: OK, this gallery should let you

show your video here and have a party. I was doing a lot of things in video form. Jaiko Suzuki would have this party,Tokyo Mon Amour, that everyone met everyone else at. She’s a musician and she would make all these Super 8 films of all the kids around at that time.

From the beginning it had a lot to do with collaboration, with lots of different people, including Ninja. How did he inspire you? What did you learn from him?

Telfar: He was a legend. He started a lot of things, but he was also chilled and well respected. He was never too cool to know certain people; he really knew everybody.

He and these kids were driving around in his van?

Telfar: Yeah, it was all these models and he was like: when you have a show, you should book her and her and her. He was always trying to put something on.

So House of Ninja was both a dance company and a model agency?

Telfar: I think he did a lot of different things! He was putting on and producing shows. I didn’t know he was unwell.

And who were your other fashion influences?

Telfar: Yohji Yamamoto. Jean Paul Gaultier is one of my favourite designers, but I also love International Male. I like everything, really. I have learned not to say I don’t like anything, because it all might come in useful for what I design, in my sort of repurposing.

You have an infinite curiosity?

Telfar: Yes, if it has a genre, I want to add my two cents to that genre and take it somewhere else. That is how I like clothes; there isn’t a colour or shoe I don’t like. I see things I don’t like as a challenge.

So there is this show with Vice, which is a beginning, and then in 2005, you start the label.

Telfar: Yes, that was when I began making things with my own fabrics. Basically, Vice ordered a bunch of T-shirts and I invested that money into making a new collection. People were not taking me seriously; I was going to shops – I was maybe 18 – and just showing them stuff. I was very tough. I’d say: ‘Look through these things, try them on.’ But they were all like: ‘You should really try and get on the seasonal calendar, and have a lookbook and a line sheet, instead of just walking in here with a pile of clothes.’ But that was how I started to work, making stuff, and that became a reason to do a show.

Tell us about your first solo show.

Telfar: It was in the same vein; I did three shows based on club nights. I used to hang out at South Park, a club in Brooklyn, so I did the show there, which was all lesbians and voguing. Everything was a twist on what you thought it was – like, you thought they were boys, but they were girls. After that, I used club nights and videos I was doing. That’s how I was presenting things.

‘I have learned not to say I don’t like anything, because it all might come in useful for what I design, in my sort of repurposing.’

Telfar’s slogan is: ‘It’s not for you – it’s for everyone.’ When and how did that come about?

Telfar: Around the Berlin Biennale.

Babak Radboy: It was before that, around Mainstream Fluid, which was our first collection that represented the brand as we wanted it to be.

Telfar: We were playing around with this idea of an underground brand being mainstream.

Babak: Our first slogan was ‘It’s Extremely Normal’; that was in 2013. We changed it because of normcore. Everyone was like, ‘Oh, that normcore brand’, and then we got closer to the essence of

what we were trying to say – a reaction against that type of hyper-marketed ‘identitarian’ clothing.

Against classification, in a way?

Telfar: In a way. That is the point of my brand in the first place. I wasn’t allowed to wear certain things that I now get a kick out of wearing – I don’t need anyone to tell me that that is fine. You choose for yourself.

Babak: That is why the brand has no gender. It doesn’t subscribe to any bourgeois categories of taste. We think of fashion as an applied art, such as painting, but its first purpose is to separate people between who owns the house and who paints the house.

Of course, the mainstream fashion industry didn’t get that to begin with. You were too modern for them. Do you think that it was a form of discrimination, in a way?

Telfar: It was menswear showing in women’s week and journalists were like, ‘No, my editor would never write about that’, and, ‘Oh my god, someone was wearing a backless shirt and everyone

was moving towards the most normal, disgusting clothes’. American fashion was turning into celebrity fashion and it was the beginning of the Us Weekly era:you needed Paris Hilton to wear it before anyone would write about it and consider it fashion. That is what it was like. Other guys were there, and they’d say, ‘That was the best thing I saw this week, but I can’t write about it’, or they would make references but without mentioning my name.

As well as the fact it is genderless, you also anticipated the now-common fluidity between art and fashion.

Telfar: That’s what made me think later on that the art world was the way out, to make money and be the designer I wanted to be. I quickly got out of that. It is thanks to Ryan Trecartin. We’ve worked on so much cool stuff together and we seamlessly connected.

When did you meet Ryan?

Telfar: In 2004, in New Orleans.

You know, Ryan is the reason I started social media.

Telfar: Really?

Five years ago, I was having breakfast at his house in LA with him and Kevin McGarry, and he just took my phone and downloaded Instagram. He had a lot of photos because he had got an early start on it, and then he told all his followers that I had joined Instagram.

Telfar: He actually introduced me to Instagram, too, because I was… I am still not on it, really.

I got quickly addicted.

Telfar: I look at it all the time, but I just don’t post anything. I don’t want anyone to know.

It is more than a collaboration with Ryan; it’s also a friendship.

Telfar: We’ve been having fun! When I met Ryan, I had always been doing what I was doing. He was in New Orleans, then Katrina happened and he moved to Philly and started working on his movies there. I can’t really tell you how Ryan’s process works. He would write things for days, and then you would be on set and the script would be out the window because something else would happen, like, ‘Drive this car into the stream!’

Babak: Telfar played different characters in all those films; it was really fun.

Did you do the clothes, too?

Telfar: No, I didn’t do any of the clothes. We would go to Kmart and Lizzie Fitch would style everything. Doing that actually inspired a lot of things, because we would get the most horrible

clothes from every walk of life and later I started to adapt them. We would dress up in cool things and tape stuff.

Babak: Then they did some installations with you.

Telfar: The first time I worked with Ryan, I went to LA and I wanted to do a show that was based on a surreal situation that would then be the lookbook. I’ve always wanted to work in a commercial way and make a beautiful art piece, and I wanted the show to be both a showroom and an art piece. That is how we started showing things. It would be an installation or a shop that Lizzie Fitch would construct or a video with Ryan. I started to create installations and that is how I started to work with

New Galerie. They began to produce new art pieces and then I did a video game with Ryan, too.

‘I cannot stand what people consider to be cool. I always want to go this way when everyone else is trying to go that way.’

Tell me about that.

Telfar: The video game was called TELFAR Style. It had a really cool early Internet look and it let you do the styling yourself. We made it with a Lizzie Fitch mannequin as the avatar and you could

style all the looks. Then we picked the winning looks, styled by people from all over the world, and those were the ones I showed on the runway. It was a two month process, at a time when my styling crew was not around, and I thought it would be really cool if it was styled using the computer. People could pick the colours of all the looks, and we dyed the clothes for the winning looks. Things started off all white at the gallery and you could pick the colour and the style. It was a really cool group of winners, and they got to see the runway show, which happened during a blizzard.

Babak: That was the show when I decided I wanted to work with Telfar. I have to say though that everything you just described was basically crowdsourcing before the word crowdsourcing existed.

It was ‘see now, buy now’, before that was a thing. These things were done for fun and with total impiety towards what separates fashion and commerce and art. That’s now become totally normalised for all the big brands.

Telfar: I’ve always wanted my stuff to be a complete contrast to whatever fashion people think is fashionable. I want to be as far away from that as possible. I cannot stand what people consider to be

cool. I want to go this way when everyone else is going that way

So, a certain contrariness?

Telfar: Yes, I love to be really confusing and converse to everyone else.

Confusing can be interesting. There is actually some literature about ‘simplexity’, which Wikipedia says is ‘an emerging theory that proposes a possible complementary relationship between complexity and simplicity’.

Babak: Isn’t that also a sexually transmitted disease? [Laughs] There were a lot of things about language in the collections too; we wanted it to be hybrid, to have secret meanings.

You anticipated this now-common idea of participation, like involving the customers in what you put in the stores. Can you tell me about that? Was that idea there from the beginning?

Telfar: We’ve been a different brand since the beginning. We are not going to sell things in the same way as other brands; we have different customers. We are selling things to people like me who don’t buy anything. We are trying to think how people actually think.

Babak: A lot of the people who love the brand do not follow fashion at all; they are art people. They don’t buy anything, not even this brand – which is really annoying! We are having to teach them how to shop…

Telfar: …for clothes that essentially don’t exist. Plus, for some pieces you cannot find anything else like them anywhere – not yet anyway – so people don’t even know how to put them on. That’s why a video or any kind of interaction with the clothes is so important. It’s just not enough to see them on a

hanger because you won’t know what they are. I want stuff to look really normal on a rack, but completely different on your body.

There have been other people who have been instrumental in your work. Kelela, for example.

Telfar: She is one of my best friends, one of last season’s musical collaborators, and a muse who I dress. Then there’s DIS Magazine, which since the beginning, has been the only platform that

would write anything about what I was doing. No one was covering it, so that was like the only way to see the stuff back then. Other people… well, there’s Babak, of course, and Avena Gallagher; she’s a stylist.

Babak: She’s my partner; she started before I did with Telfar.

What’s her role in the mix?

Telfar: She refines and understands my design situation; she knows what is not me, what would look better. She is the guiding voice who understands me because she has been there and seen what I’ve done before. She styled my first show, which was different variations of sweatsuits in different fabrics. I don’t think there were even any shoes. Avena understands what goes on in New York and what goes on in Europe, and what actually makes sense. We understand a lot of different things; literally, she is the tiebreaker between me and Babak.

And then what about Kelela?

Telfar: Kelela… I mean, she’s my boo. It is really hard to dress a celebrity or a performer, but she is the one person who makes sense. My clothes just look so good on her; her vibe is just so over the moon. Seeing her grow and become the pop star she has become has been really cool. When people see her they think about me, too.

Babak: The celebrity thing is tricky because for us. When something is original and doesn’t follow a trend, it becomes difficult for people to want it. They want, for the most part, something they have already seen. They want to be adjacent to someone fabulous and model themselves on that person.

Even celebrities want to be adjacent to another celebrity. And Kelela, from the beginning was just like, ‘No, I like that’. She absolutely chooses to wear it.

Telfar: I met her in 2012 or 2013 through all the music kids in LA; they were like, ‘There’s this girl from Maryland who you should really meet’. Going back, we actually knew the same people. My cousins grew up with her; she went to school with them and knows them well. There is a lot of crossover. We were just hanging out together over Thanksgiving and going back though our childhood and realized that we were right across the street but didn’t actually know each other.

‘A lot of the people who love Telfar don’t follow fashion at all. They don’t buy anything, not even this brand. We have to teach them how to shop…’

There are also other people of your own generation. People like Shayne Oliver whom I’ve also interviewed…

Telfar: Shayne is like my first boyfriend, best friend; he walked my first real show. He has always been around. The first time I learned about what an operations manager is and why you need these things to make a business work, it was with him. I always thought I was a one-man army, that I could do things from a basement, and that things would just work out. He showed me that you need to build a team. Shayne and Leilah Weinraub at Hood by Air built this infrastructure so that I wouldn’t make the same mistakes they made. I learned how things work and don’t work. They really just taught me a lot of how an untraditional business can work.

And Raul Lopez?

Telfar: I have known him for as long as Shayne, basically from hanging out on the street. He is always busy. He has his own line and he works for other people. I think he is going to be the next New York fashion business. He is the coolest and most established young designer coming up right now. There’s also Fatima Al Qadiri; she’s one of my big musical collaborators.

I did an interview with Fatima and her sister Monira…

Telfar: I just met them in Dubai.

They are so amazing together.

Telfar: They are like the same person, and you can see where it comes from when you meet their mom.

She is great.

Telfar: I was supposed to go to Kuwait because she wanted to do a painting of me. We had a really great time in Dubai.

What is the role of DJing in all this?

Telfar: It’s for the money!

When did you start?

Telfar: Probably in 2006.

Let’s talk about the DJing. Who were your heroes and how would you describe your style?

Telfar: I have been blessed by not having to do anything I don’t like doing. So even though I’ve said I don’t like to DJ now, that’s not 100% true; I do. It’s just I don’t like doing it on a weekly basis; I like to do it for fun. I used to have four club nights a week; that’s how I paid for the collection and could still go to school, as well as network and have meetings. I would meet people at two in the morning and then go home and do whatever I had to do. But I would go to school at six in the morning having DJed until four. And that was basically how things worked. I would DJ at the Cock, which was on Second Avenue. After a while I hated it, though. As much as I love the community, I don’t need to be out every night any more. I’m at a different point in my life now.

Let’s talk about the legendary runway shows. You work on them together, so I wanted to ask you both about your favourite shows.

Telfar: The show that Shayne was in with 2006 Gen Art was pretty cute. Afterwards, the installations and exhibitions with Ryan were good.

Any in particular?

Telfar: In 2011, we did something at White Box, a gallery on the Lower East Side. They made me sets and we had beds and these beaten-up mannequins from American Apparel, and that was how we displayed the clothes. Then there was the Shop Mobile in 2013, which Lizzie Fitch built, and that basically lasted for two seasons. I would make installations and put the new clothes in this shop that she built for me and which could travel all around. The video we made for Spring/Summer 2014 was the first thing Babak and I did together…

Babak: I love that TELFAR Style show when it was styled from the game. It was something about seeing that show and the fact that there were no press or buyers, just our friends. I loved the show,

but it also made me really mad and it made me want to work together. The idea of working together was like: ‘How do you take this thing that you are doing and turn it into a brand? And how do you make that brand as weird in its own way as the thing that you are doing?’

Telfar: We are done with a collection about three months before the show, and then we work on video and the assets that are going to sell it. It’s making sense of what the fuck we’ve made. We shoot a lookbook of the clothes, then we make a video of the clothes, and then we make a T-shirt of the stuff that goes into the runway collection.

Babak: It’s the exact opposite of normal fashion. We do the campaign before the show and then the show is the campaign for the collection. At Mainstream Fluidities, the Spring/Summer 2014 show, there was a 20-foot video screen that I had convinced someone in Texas to give me for free. You saw a model on the video screen wearing one look and then the real person came walking out from behind it, so there was kind of a time warp; 30 looks, 30 people, no changes.

Telfar: We had 30 other models coming out wearing T-shirts of the models who had just come out before them. It kind of went over people’s heads, but it was all based on this idea of fast merchandising. Where you could buy a T-shirt with a look printed on it because you loved it so much. Like, ‘I love look 22, so I’ll buy the T-shirt showing it and then I’m out of the door’. And we got our money and didn’t go broke after doing that show. That’s when we wanted to start having shows like we are having right now.

Babak: We also know that people aren’t always ready for these clothes, even if they like them. So they buy a picture of the clothes to show they like them without having to risk wearing them.

‘I used to DJ four club nights a week; that’s how I paid for the collection and could still go to school, as well as network and have meetings.’

A T-shirt in that sense is almost like a…

Babak: A lookbook.

So you started with T-shirts and then that never really went away.

Telfar: No, it never went away. I love a T-shirt, in all its different forms. It was also about using the most accessible piece. I mean, if you have two arms and a neck, then you can wear one.

It is democratic.

Telfar: Also, we were creating a part of the collection that we thought was going to make money. Because there was, and still is, a two-year period between when I design and make something, and when people desire and want it.

So, you are always too early?

Telfar: Two years too early, although maybe now we are like 18 months too early.

Babak: That was the other thing that convinced me I wanted to work with Telfar. I would do little things for him and he would pay me with clothes, and I would always find I was looking in the collections that were two years old and asking for that. He would say, ‘Why?’ and I was like, ‘Because you are so ahead!’

Music plays a big role in these shows, like in Spring/Summer 2014.

Babak: That was a music video.

Who made it?

Telfar: Future Brown, a group formed by Fatima Al Qadiri, J-Cush, Asma Maroof and Daniel Pineda. Their first video was our lookbook.

Telfar: They were debuting this brand new song. What was it called again?

Babak: ‘Marbles.’ The crazy thing about the video is that it was also the last year that Facebook was chronological, before the new algorithm came out, so we were able to get more views than a Gucci video; we got 200,000 views in a couple of days.

What was the next show after that?

Telfar: Our massive show at the New Museum; we treated it like an amusement park or a concert. We created a store inspired by Kmart, and then Kmart ended up working with us. It was the same season we introduced the Telfar bag, so we had this shop full of brand new bags, which you could buy right on the spot, and the runway show was upstairs. We actually shot the lookbook and made a video, like we’d done the time before, but we made these little 3D-printed action figures of all the looks. We thought people would come downstairs and buy the action figure of the look they wanted, but most people stole them. Even our friends stole them, and all the models stole their own!

Babak: It was like an expo. The idea at that point was to create this profusion of different representations – the little version, the T-shirt version. Instead of an underground feeling, we wanted it to be as mainstream as possible.

Telfar: Without losing money!

Babak: It became the way we made money. That’s why that show was so important – it created the new model of how we could exist.

‘The collection’s completed three months before the show. So we work on video assets that are going to sell it – making sense of what the fuck we’ve made.’

That was in New Museum and then…

Telfar: After that we were like, ‘We are never doing that scale of show again!’

What came after the museum?

Babak: It was the acoustic show, Spring/Summer 2015.

Telfar: Oh my god, yes! That was the season we didn’t know if we were going to be able to do a show up until the morning itself. I think that was my favourite.

Babak: It was beautiful.

Telfar: The rug had been just pulled out from under us and we just winged it, literally. All we had was a piano and chairs, not even lighting, and that was all we could afford. That was the most beautiful show ever.

Can you describe what happened? Who played the piano?

Telfar: Nathan Whipple, he is part of Hairbone; we’ve known him forever. I was inspired by Christmas at the mall, how they play Christmas music on a piano and I thought: ‘I want to hear everything disgusting that we’ve heard on Fire Island.’ We wanted to hear Taylor Swift, Maroon 5, Lana Del Rey, just the worst songs, but played by Nathan on a piano, which made them completely different. It was also about our understanding of what is gross, commercial, and our niche – how that is us actually and that’s what pop art is. That was the one collection in which we understood so many different things.

The shows vary widely, but there are certain leitmotifs in the clothes. One has been there from the beginning, from that first three-T-shirts-in-one: the work plays with deconstruction and reconstruction. In the past you’ve talked about taking a top and making it a sweatshirt, turning a dress into a T-shirt, leggings and so on. You seem to enjoy pulling things apart and then recombining them.

Telfar: I like to make something that is completely new, yet also sort of understandable. Like a tank top that is a tank top, but not doing the normal thing a tank top does. So it is deconstruction that adds functionality to something.

Babak: It is close to deconstruction and appropriation, but it is also not those things. The reason why is because the philosophy and subjective position of why it is being done – even if it’s the same action Margiela might have taken – is producing something different. Rather than fashion, it is producing a construction, something always at work. The process has more in common with Pierre Cardin and Rudi Gernreich, but using the same methodology of removing, repurposing and combining.

Telfar: And also just reshaping things. I see clothes when I’m biking around and I am flying by someone, and if I see someone wearing something weird, then that gives me an idea. Like when I made a shoe. I had seen every office lady in a ballet flat and I thought it would look good on me, so I made a shoe inspired by that style. I didn’t deconstruct it; I just repurposed it, so it became a man’s sneaker based on a ballet flat. It is a basic shoe that will never go out of style. That is how I think about stuff. My take on this shoe is that this was a woman’s style in the early 2000s, and now in the 20-teens, it’s become a men’s shoe to wear with skinny jeans.

There is an interesting paper called ‘Steps Toward the Writing of a “Compositionist Manifesto”’ by Bruno Latour. It seems quite you. [Reading from his phone] ‘In this paper, written in the outmoded style of a “manifesto”, an attempt is made to use the word “composition” as an alternative to critique and “compositionism” as an alternative to modernism. The idea is that once the two organizing principles of nature and society are gone, one of the remaining solutions is to “compose” the common world. Such a position allows an alternative view of the strange connection of modernity with the arrow of time…’

Babak: That is what we have been doing. For the past year or so, we’ve been partially moving away from a more nomadic and representational model towards something that was more about presence and making an alternative world. It’s not irony, it’s not critique, and it is not discourse or conversation. It’s just about beginning to build other avenues, and that is what our shows and the entire strategy of the company are about now.

‘We are both political refugees; we are both afraid of voting. We just are trying to live the way we want to live.’

But it is also political…

Telfar: It is political just because of the type of people we are. We just want to be free, it’s the fact that…

Babak: It’s the fact that it is fucking ridiculously hard and that it is not of our choosing.

Telfar: We just are trying to live the way we want to live. I try not to be political. I don’t want to be; I’m not really that person. I don’t say much about politics; I do what I need to do for me and my family. I don’t care.

Babak: We are both political refugees; we are both afraid of voting.

Telfar: My parents were like, ‘You mind your business and you do what you need for you, and that is all that matters’. I don’t have any attachment to having to participate in certain things.

For the first five years of your life, you lived in Liberia.

Telfar: I was born here in Queens, moved to Liberia, and then the war happened, and we moved back to Queens.

Which war was that?

Telfar: The Liberian civil war. I came back here when I was five, in 1991.

And you came here as a political refugee of…

Babak: The revolution in Iran, but in 1986. My father was the mayor of his town after the revolution, and he was a guerrilla for 15 years before the revolution. We left, not because we were with the shah; my father was part of the revolution. He was just a Marxist, not a violent actor.

It’s interesting that you are both political refugees.

Telfar: We are similar in lots of ways, when we see where we are in America now.

Babak: We have a different subjective position. There is a weird way in how we especially don’t fit into the art world, and its discourse.

Telfar: Or the fashion world either. We don’t particularly fit into a lot of places – and I’m not even really trying any more.

Babak: Neither of us functions by using taste to mediate our process. We are against taste.

But you never wrote a manifesto about that?

Telfar: No, because I don’t particularly want anyone to know; I am cool with it. At the same time, I am always going out the back door when it comes to good taste.

Back to the shows. Are there any others we should mention?

Telfar: Yes, our last show – I couldn’t believe it. The next day I was walking around and thinking: ‘Is this how celebrities feel?’ Because people were saying: ‘That was the best show, man!’ It was really cool to mix things up that much and really gross some of our friends out.

It was a concert?

Babak: Just a concert.

Who was playing?

Telfar: Kelela, Kelsey Lu…

Babak: We had an idea about how to create collective music. We knew we needed to work with musicians, and we had to leave the vector of fashion as a distribution point, and move to the vector of music as a distribution point. I actually got that idea from an Arthur Jafa quote, where he explained how he wants to make a black cinema that’s like black music, because black music makes money. Black music allows you to carry out your vision whereas cinema doesn’t, like fashion doesn’t. You need at least $2 million to even start a ready-to-wear company. You are faking it until you have that. So we wanted to work with musicians, but then make something completely synthetic that revealed a kind of music that sat outside the commodified form of music, in the same way that the clothes we are making are essentially about something collectively owned, which is style itself. So everybody solos and does background,and then the music you end up with is something that everyone does together in relationship to us – a sort of gospel song.

So there were no models?

Telfar: There were models, because Alton Mason is a model, but he can sing! We turned him into a singer. It was a new avenue for people.

‘You need at least $2 million to even think about starting a ready-to-wear company. You are faking it until you have that.’

Tell me about the models you do use.

Telfar: We aren’t trying for diversity. Not everyone needs to be in fashion.

Babak: This is an outside narrative that gets put on us, and we just use it where it is useful. When people call our show inclusive, I’m like: inclusive of what? We are brown, it is not inclusive! It is just people who we think look good. We’ve started using the word non-racial instead of inclusive or diverse. It is a non-racial, non-gendered show. We never heard any news about how racist the industry was, and now we just get a lot of news about how diverse it is. So, when was the change?

Telfar: I don’t remember the change and I don’t need that. I don’t need someone being like: ‘Oh, because you are black, I will buy that bag.’ Buy it because it is good! You are actually being more racist and retarded if you think like that. It’s cool if you buy it, but if you do it out of pity, pay more for it!

Babak: Before, no one would write about Telfar’s clothes, and now they write about him as the ‘black designer’. They write about his community and his this and his that. But the reality is that that ‘community’ thing is the way that black art always gets spoken about.

Telfar: It is also just so popular and PC to think like that. To think that it is helping the situation, and I am like, no, it’s not.

Babak: The reason we talk about money so much is because that is what’s helping. If there is no money, no transfer of funds and power and security, then I don’t care how many people appear

in your runway show. Who owns your company? We get annoyed when a big mainstream company does a non-gender fashion show with models of colour because we’re thinking, ‘Those are our

customers, why don’t you sell to your customers?’

Let’s talk about your partnership with White Castle. You’ve said that you grew up on White Castle, that it was the first restaurant you can remember when you came back from Liberia to the United States.

Telfar: The one I knew from growing up was on Queens Boulevard and 57th Avenue. My mom used to work in Queens Center Mall nearby, and we would go over to White Castle to get the small burgers on Saturdays. That was my first experience. It was literally the smallest burger you could get. Then later, coming back from the club, we’d go at 4am or 6am because it was the only place open. We were introduced to the guys at White Castle with the idea of sponsorship, and we threw a party with them.

Babak: A couple of days before the show they asked: ‘Do you want to do an after-party in our restaurant?’ And I replied: ‘Is that legal?’ And they said: ‘Yeah, sure, no problem.’ It’s not like any normal sponsorship relationship. The vice president of White Castle came to the show and the party, and he was this completely unexpected person. They are a family-owned company, and we feel like we have an uncle now.

Telfar: He was the one doing the lighting at the party!

Babak: He was turning the lighting on and off to create disco lighting!

Telfar: It was just an Internet sensation after we did that. People couldn’t believe we did it. Before it happened, people had been scared to come because they thought the police were going to come, but none of those things happened.

Babak: It was the best party ever.

Telfar: So many people were mad they didn’t come because they thought it was just another fashion week after-party.

Babak: Because they went to the Wolfgang Tillmans thing.

Telfar: [Laughs] Bad luck! We did it again the season after, and that was a mob scene, crazy.

Babak: It started the whole downmarket trend in fashion, like collaborating with Hooters, Porn Hub and Trojan condoms. But the reason we did it was because we couldn’t get fashion sponsors! No make-up or hair, nothing.

Telfar: Any sponsors were like: ‘OK, so you’re a doing a men’s show, and who is in that? Any celebrities?’ All the rules that we actually subscribe to as a brand just don’t go with fashion sponsorship.

Babak: And that is why we did Kmart.

Telfar: Things that other people wouldn’t touch, that fashion people wouldn’t touch.

Then it became a trend.

Babak: It was an idea about how we love lower-working-class brands. We love American Eagle…

Can you talk about the uniform you’ve designed for White Castle?

Telfar: During my entire education, I was running away from wearing a uniform. All my other brothers went to private school and I went to public school specifically to wear the clothes I wanted to wear. I think we first suggested making White Castle’s uniform for them.

Babak: The amazing thing about what happened is that it’s not just a sponsorship deal – we actually make the uniforms. So we are now delivering 50,000 units a year to White Castle.

‘When people call our show inclusive, I’m like: inclusive of what? We are brown, it is not inclusive! It is just people who we think look good.’

And do other people want to buy the uniform?

Telfar: Yes, but we are keeping it so that if you want one, you have to get a job at White Castle! Our friends have them. But we are also releasing some things that you can buy at the locations. We are making a Fall one for them at the moment; it’s a whole new income stream, designing uniforms.

And what about Rikers Island?

Telfar: Yes, that was the RFK bail fund that we partnered with to release the capsule collection. Babak found it.

So that was a social project?

Babak: We had this project with White Castle and then realized that we couldn’t have our friends sing at a launch show if a corporation was going to make money from it, so we decided that 100% of the proceeds would go to charity. But we didn’t know which one. A charity is what is going to fix things, but the bail fund was different…

Telfar: While we were trying to put out the work that we did, we began to see the importance of that charity. The idea was to have this party in LeFrak City, in the White Castle I had always gone to, and have these performers like Noreaga do something in the neighbourhood. But the idea got shut down – even though we did have permits.

Babak: The day after we sent out the invitations and announced that the money was going to help get minors out of Rikers Island, we heard that the police held an emergency meeting; the borough chief, the antiterrorism, anti-drug, the hip-hop units. Twenty people in this room and even though we had all our permits, they shut down the party. They said it was impossible to do that party at that location.

So it was a form of censorship?

Telfar: It was a lot of different things.

Babak: Imagine the time, the heart, the six months of development we lost. The sponsors pulled out and we lost money, and it became real. First of all, we chose the charity because we knew it was challenging. It wasn’t paying anyone’s salary; it was pure – just paying someone’s bail. And the bail fund doesn’t pretend it is solving any problems; it is just getting people out of jail. The fact that is it so limited makes it perfect to me. Then the press wouldn’t even write about it. We told them the police shut down our party and they were like, ‘Errr, OK’. But we found another location in 24 hours and moved the whole party there and 1,500 people showed up and the stuff sold out immediately.

Tell me about the Telfar World Tour, the exhibitions, and what they mean?

Babak: The World Tour idea is because we are doing a unisex line, which is totally unusual, so we thought we could do the men’s sales in Milan, a women’s show in New York, then back for women’s shows in London with one show. We are literally going around the world with one concept, like a musician does.

Telfar: We were thinking about the schedule and cool exhibitions that could make sense, and can explain the brand.

Babak: The concert tour for us is basically an escape route out of fashion. Because we can just create something with a musician on tour and sell it in different cities and not do these cycles.

Telfar: During the first show in Milan we introduced two looks from the collection that were worn by FAKA, two performers from South Africa. It was basically a performance, and we also released a new photo of me, it was the tallest – two stories tall! It was a chance for me to meet FAKA, because we were obsessed with them just from the Internet. They flew in for 12 hours, we met, they did that performance, and that was the debut of the first two looks we were doing for the show in September. And there was a book, too…

Our project at the Serpentine Gallery in London will be a performance.

Telfar: It’s a happening. It is not on the fashion cycle. It will have its own room to breathe and just be whatever it is. It can be perceived in any kind of way, not just as fashion. Plus, London is great.

Babak: If the show is good enough, there is no reason it can’t go to six cities. And those cities don’t have to have anything to do with the fashion world. We can do London, New York, Johannesburg, Chicago…

Always the same cast?

Telfar: It could be the same theme or model, or we could create a sound that could be built into anything. It could be a song that goes on for years and years and years. That’s what we’re going to

do: go exploring and see where it goes. But right now, we just want something cool and beautiful to happen at the Serpentine.

‘I don’t need someone being like: ‘Oh, because you are black, I will buy that bag.’ Buy it because it is good! If you do it out of pity, pay more for it!’

Are you excited?

Telfar: I’m excited, I haven’t been to London since 2012. London is a rough town, rougher than Brooklyn. People eat biscuits! There are paper towels! I am super excited to go there; the best and the biggest and most important things are in London. Every time it’s like that person just graduated from Central Saint Martins and it’s like: give him this job! People believe in stuff. Here you have to die before you get what you deserve. It seems as though people just understand stuff there – the importance of fashion and culture and how they go together. Here they are just like: which celebrity has it?

Babak: We showed the documentary in Milan about how the party was shut down by the police, and seeing it there made me realize – wait a minute, America is just retarded. It is so backward. Everything we were going through seemed so alien; it is just so much harder here. People pretend there is just one global discourse and we are all on the same page, but it’s like, no.

Telfar: Europe is definitely much more mature.

And do you have any unrealized projects and dreams?

Telfar: So many! I want to have a mobile shop that is not in one particular place, but in every place; it could be anywhere in the world. I have been working on the idea and there are just really cool places

where photographically, it would just be beautiful to have a store. I want to have non-traditional retail, you know. I feel like this is the first season I have made an entire vocabulary of products. But still it feels as though they don’t exist yet, so I have the job of making them exist. But first things first.

Babak: Everything is unrealized in that sense.

Telfar: When I was 17, I wanted to develop every different kind of clothing. There is still so much in the collections’ vocabulary that we haven’t quite got out there. This jacket is a classic, but we have to get to it before anyone else does.

What about the logo? Where and when did that come about?

Telfar: Liberian English is like broken English and old English, so I didn’t really speak English when I came here. I had to take this English class at my kindergarten and my teacher used to write each student’s initials like a monogram on the board. Mine was a ‘T’ inside a ‘C’ and I really liked it. I always used to sign my name like that, so basically, I’ve had the brand’s logo since I was like five.

Babak: It is just the best logo story.

Amazing. You started shopping with your mother, right?

Telfar: She would let me try things until my dad saw it! I would also make my own clothes, and she would let me wear them on a Friday, but only on a Friday. I would wear sweatpants, but under jeans that were completely ripped all the way up to the top. I would change three times a day at school. I would turn my jeans inside out because they just looked way better. I remember when I discovered Helmut Lang and I was like: ‘Oh my god, he has made the jeans that I have been doing myself. I think that was in 1997-1998. I didn’t have any access to fashion, so when I actually saw people doing the thing that I was already doing with Old Navy jeans, it would actually piss me off; I used to think they were my thing. That is where a lot of things came from – wanting to do something first.

‘Here’s

your

new body –

get in’

Telfar Spring/Summer 2019