Fraser Cooke on the rise of the ‘x factor’.

By William Alderwick

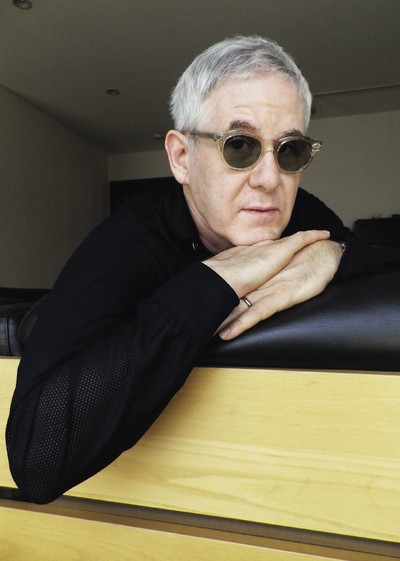

Portrait by Fumiko Imano

Fraser Cooke on the rise of the ‘x factor’.

Collaboration is a driving force in fashion and culture today. The headlines

telling us two brands are coming together, each multiplied by the other

to drop limited edition product, are now a regular fashion fixture. At their

best, these cross-pollinating creative encounters bring new techniques,

visions and design languages to a familiar product. The most iconic define

a moment and open up new possibilities both aesthetically and culturally.

Over the past 15 years, as collaborations between artists and designers

and larger brands have moved from the edges of the fashion world

to become one of its defining dynamics, Fraser Cooke has overseen Nike’s

groundbreaking – and commercially successful – partnerships with

designers including Virgil Abloh, Riccardo Tisci, Jun Takahashi,

Rei Kawakubo, and Chitose Abe of Sacai.

To better understand the dynamics of collaboration, System caught up

with Cooke – or to give him his full title, Nike’s Global Senior Director

of Influencer Marketing and Collaborations – in Paris, where he was to

launch the brand’s Women’s World Cup Collection, the kits to be worn

by 14 countries at this summer’s event being held in France. He discussed

the defining encounters that have shaped his own career, one that parallels

streetwear’s rise to fashion royalty, and curated a portfolio of the most

culturally influential collaborations of the past 25 years.

‘Sneakers had become a more immediately

visible way of differentiating yourself.’

A conversation with Fraser Cooke

Paris, February 28, 2019

‘Collaboration is another way of looking. It can allow you to look at the familiar with a slight twist or create something completely new that would not otherwise have been possible. It’s like music: certain collaborations just really capture a moment in time.

I grew up in East London. I first rode on a skateboard in 1977 during a street party for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. Somebody had a really shitty one with roller-skate wheels, but it really captured my imagination. I was at an age where I was starting to open up and that was the kick-off point for me. Back then in the UK, fashion was very tribal. You had to have a certain pair of loafers or a certain type of Dr. Martens, a certain kind of Levi’s, Ben Sherman and Fred Perry shirts. It was about brands as signifiers, but it hadn’t got to the point where you needed to layer something else on top. I remember first getting into the MA-1 jacket, in a sort of skinhead style, then the Mod thing.

In the 1980s, you had style magazines like The Face and i-D, with people like Simon Foxton and Ray Petri, and Buffalo, pulling together certain looks. They were the original stylists. But what we now call streetwear didn’t yet have a brand specifically catering to it. That absolutely started with Shawn Stussy and his Stüssy brand. Before him, there was skate- and surfwear, there was high fashion, there was workwear, and a few people mixing it up. But he was the only person who pulled together everything that was happening at that time. I first saw Stüssy in Thrasher magazine and I saw all these different elements – hip hop, surfing, skating – all pulled together by this one brand with its graffiti tag-style signature logo.

I left school young at 16 and got a job in the Stock Exchange. I really didn’t like it from day one; I was only there because I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I used to spend my time down at WHSmiths in Liverpool Street Station looking at magazines like NME, The Face and i-D, and Record Mirror looking at the DJ charts. I was really into music by then, buying 12-inches. Then I met a friend who worked in a Vidal Sassoon hair salon on South Molton Street, and I felt like hairdressers and shop assistants were somehow operating in this creative zone. The first Comme des Garçons store was over the road from the salon and Yohji Yamamoto was there, too. I saw this creative world – and I wanted to be a part of it.

That was why I started cutting hair – it got me closer to what was happening in London. I started going to places like the Wag Club and warehouse parties, the nightlife side of things, and eventually began DJing on the side. After a while I realized that hairdressing wasn’t what I really loved and was hired by Shawn Turpin who had a store called Passenger and wanted to buy American sportswear. So we started going out to the US on buying trips, mostly to New York, which was very inspiring in the late 1980s. My mate Karl Templer was doing the hype section of The Face magazine, laying out new cool stuff. I gave him the T-shirts I sourced from an American brand called Pervert and he put them in the magazine with my phone number alongside. Before I knew it, people were calling to stock them and I became a de facto distributor of American T-shirts. It was really a very fun means to an end because it meant I had to go to the US, where all the stuff that inspired me was coming from, like skate, hip-hop and the cross pollination with post-punk.

A few years later I met Michael Kopelman who had started [clothing importer and distributor] Gimme 5 and had been working at Black Market Records. He knew my flatmate James Lavelle who had just started his record label Mo’Wax. I knew Michael was affiliated with the International Stüssy Tribe and was close to some of the interesting people on the scene like James Lebon and a whole West London creative fashion crew who were a few years older than me. We really came together when his previous partner left Gimme 5, and we ended up doing a bit of travelling together, going over to Los Angeles and San Diego to these trade shows that were primarily for surf and skate, and were really a breeding ground for the beginning of streetwear. We decided to do something more solid together after finding a common affinity. That ended up being the Hideout, our store that was initially named Hit and Run. Michael ran Gimme 5, which was representing Stüssy and breaking Japanese brands like Hysteric Glamour, Bathing Ape and Goodenough, while I was managing and buying alongside him, out front in the store. The Gimme 5 experience was really formative for me – the company pulled together the Stüssy thing, and the best of the UK, Japan and the US, which is where all this started.

Once we’d been doing that for a few years we opened the sneaker store Foot Patrol. It was the beginning of the movement of sneaker stores at the time, of which we were one. There were also Alife Rivington Club in New York; Undefeated, which had just opened in LA; and Atmos and other places in Japan. Sneakers were becoming a more immediately visible way of differentiating yourself and the industry had started doing special colours and editions. Adidas had ventured into the beginnings of ‘official’ collaboration with Run DMC in 1986, which was very early on. Nike was collaborating in a different way at that time. It had always worked with athletes from its inception, but it wasn’t yet doing it in an overtly commercial sense. In the late 1990s, it did do some early collaborations with Junya Watanabe, but they were in really small quantities that would go in the Comme store.

‘In the 1980s, what we now call streetwear didn’t yet have a brand specifically catering to it. That absolutely started with Shawn Stussy.’

Retail is a real labour of love – you’ve got to really be into it to do it well for any length of time. That’s why it’s normal that a place like Colette, for example, wouldn’t last forever. A store is a moment in time, and that’s how we saw The Hideout, a gathering spot for a scene, for a group of like-minded people in London. For me, Nike was the next step.

The good thing about Nike is that it’s a brand people have an emotional connection to. It goes beyond being a sports company despite the fact that that has been its sole focus and roots from the beginning. Many of the products have taken on a real cultural currency that transcends their original intent. At that time, a few people there – [CEO] Mark Parker, [special projects director] Sandy Bodecker, John Jay at Wieden+Kennedy as creative director, Trevor Edwards, who left Nike last year, to whom I’d been introduced by my good friend Giorgio de Mitri of Sartoria and Stash – began exploring broader experiential avenues. They knew there was a subculture embracing and adopting elements of Nike in unique and diverse ways that went beyond the pure intent of the brand, and they wanted to try and harness and build on that creative energy.

It was natural for Nike to want somebody who was already part of that sub-culture to work on the project. They needed a person who could naturally navigate the scene on their behalf, and I guess that’s how I fitted in. Initially, I worked with interesting retailers running small boutiques, people who were all friends. It was only a couple of thousand pairs of shoes here and there, sometimes hundreds or even 50 pairs of Hyper Strikes, but they were highly sought after, and generated a lot of energy and excitement at a very small scale. What’s changed over time is the number, depth, breadth and the richness of projects that are out there. Product has become the focus, and for some brands the other stuff – like the reason to exist or the storytelling – isn’t always as prominent. But when these elements are considered, you can start bringing people into a bigger idea, an elevated experience of the brand – that’s the goal. Because consumers expect a lot from collaborations now. We’ve trained people culturally to value them and it’s become the norm. What hasn’t become the norm is bringing a thoughtful depth to the way they’re presented. When we did the Ten project with Virgil Abloh, we wanted it to be about more than just lining up outside a store. So we invited customers to come and listen to Peter Saville or Nick Knight or Michèle Lamy, so they walked away with more than just a product. The whole package created a valuable memory.

Sometimes it’s about getting people to look at a story that they wouldn’t otherwise look at.

Nike doesn’t need to collaborate by just slapping somebody’s name on a sneaker. That’s not enough. We need to do stuff that truly has synergy, something that tells a richer story. The brand needs to be learning and vice versa; it’s an exchange. It is interesting when you can pull the partner into your space, while they pull you into theirs. That’s how you end up with something completely new. When you’re with somebody who has a distinct personality and ideas about what they do, how do you find the right place where you’re both comfortable? How do you find a new language? The best people really push you to do stuff that’s creative. And they get to express themselves once they embrace that.

Michael Kopelman used to say if my nose itches, I scratch it, I don’t ask why it’s itching. That makes sense to me. I do analyse a lot, but a lot of it is gut feeling and what feels right at the time. It’s instinct driven.’

‘When Nike did the Ten project with Virgil Abloh, we wanted it to be about more than just hundreds of people lining up outside a store.’

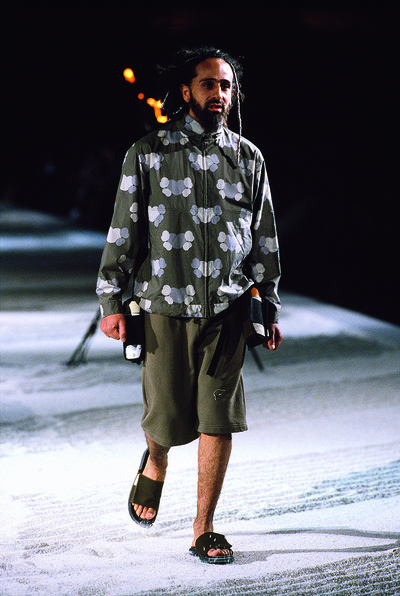

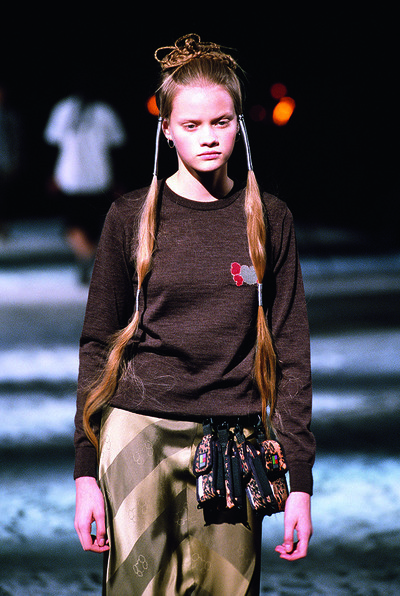

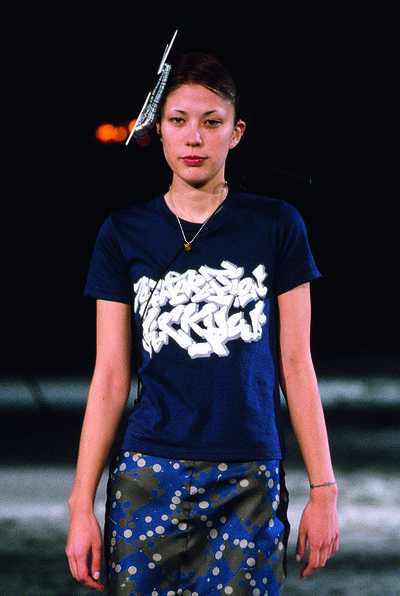

Undercover ‘Generation Fuck You’ × Kaws, Futura, Stash and WTAPS at Toho Studios, Tokyo;

‘Teaser’ Spring/Summer 2000 collection and show (1999)

This was just so far ahead of its time. It’s normal now to have high fashion mixed with street, but back then it wasn’t at all, apart from a few people like this out in Japan. Futura, Stash, and Tet from WTAPS worked on it with Jun Takahashi. At that time all those guys – Jun, WTAPS, Neighborhood, Hiroshi Fujiwara and Nigo – were part of one extended interwoven family. It was that Harajuku scene, so it wasn’t strange for them to work with each other at the time. It was a collaborative effort. It certainly captured the mixture of the scene that was going on in London, New York and Tokyo. I went to the show. It was before I moved to Japan, but I was already buying for the Hideout and we were already affiliated to Undercover. I already knew Kaws and Futura through Stash. We were all in Tokyo at that time, an international group of friends. Jun staged the show, which was overtly street, at Toho Studios. That was where Kurasawa shot a lot of his films and part of the inspiration behind the show was Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai and his other classic films. Jun was cutting and pasting together all these different elements. He brought it all together in a new and fresh way and elevated it through his great design enhanced by his art direction. I first met him in Harajuku, on my first trip to Japan in 1997. I went there to help Hitomi, who works with Gimme 5, escort models to an Undercover show. We flew over 10 or 12 models from London to Tokyo to walk in the show. It was nuts. I met Jun outside a bar called Hide and Seek in Harajuku; we had a chat and I immediately thought, ‘What a nice guy.’ He just seemed cool. I was dealing with Nigo and the A Bathing Ape people, but of course Jun used to work with Nigo as well. They had a store together before, so it was all within that same circle. Within a year I was going back and crashing at his house on my buying trips to Japan. ‘Generation Fuck You’ was very memorable and if you did the whole thing again and made a Generation Fuck You 2.0, it would still be relevant and modern, even with the same people. Futura painted the new Supreme store this season. Kaws just had one of his paintings sell for over $14 million in an auction of Nigo’s collection. It’s funny how people roll in and out of being in vogue. It just feels right again now.

Nike HTM woven sneakers (2002)

HTM is an experimental design group made up of Hiroshi Fujiwara, Nike shoe designer Tinker Hatfield, and Nike CEO Mark Parker. This shoe is from 2002 and I picked it because it’s a kind of shoe that didn’t exist before: it’s not for any particular sport, but it’s taking elements from sport. It’s more to do with construction. At the time, Tinker and his team were working with traditional techniques of how to make something comfortable that moved well with the foot; Hiroshi provided the aesthetic finish. It was when we began to be more thoughtful about footwear collaborations, not just giving people what they already had. It’s not taking an Air Jordan and colouring it up; it’s about presenting something new to the world, working both with people who are key at Nike, like Tinker and Mark, and somebody who was at the height of his street cred and has a sharp eye, like Hiroshi. The combination of these three people on this product was exciting for people who are into sneakers. HTM was an accelerator, because it started to pull disparate elements together into a more cohesive whole in a more visible way. At the time, streetwear companies were starting to pop up and people in Japan were beginning to know about the scene. Then suddenly, you get Nike, this giant, and Hiroshi, the person who pioneered the scene, coming together for a product; it supercharged the interest that was already building. It was a moment of momentum towards where we are today. It was also disruptive, because it’s a shoe that not everyone could love straightaway.

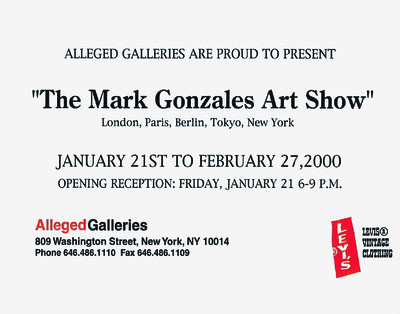

Mark Gonzales x Levi’s (1998)

So many people were into Mark Gonzales as a character. He’s such a seminal guy, one of a few who really invented modern-day street skating. He’s also an artist and this collaboration was a way of supporting his art and doing something creatively progressive together. The brand was launching Levi’s Vintage in the UK and the first project I did with them, which didn’t result in any product, was a big art show at the Tramshed in Old Street with Futura, Stash and Lee Quinones. It was a big group show where we built a complete one-on-one scale New York subway car. The back half was flat, the other half we got made by set builders who work on movies and then we displayed all their artwork. Levi’s sponsored that and wanted to do something else, so we got Mark Gonzales to paint jackets and jeans, and the brand supported a tour. It was Mark’s art applied to jackets. He hand-painted them and they were part of an exhibition. Then Levi’s reproduced the hand-painted jackets to sell and support some art shows that he did. That was a good project and the jackets looked cool.

Rei Kawakubo × Louis Vuitton (2014)

This was part of a wider collaboration with Marc Newson, Karl Lagerfeld, Cindy Sherman, Frank Gehry and Christian Louboutin. What Rei did was really interesting: take a bag and cut holes in it, so there’s almost a face, two eyes and a mouth. It’s not really fully functional as a bag any more – and I think that’s great. It’s still Louis Vuitton, but also speaks to the Comme des Garçons spirit – and that’s a true collaborative balance. This one is irreverent whereas the collaborations we’ve done with Rei needed to be more functional. They still have to perform to a standard. She’s always been more respectful of the basic form of the shoe, although there have been a few wild ones. She’s amazing to work with. Looking at this bag reminded me of a 1996 Helmut Lang and Vuitton collaboration where he created a DJ record box. They advertised it with a shot of Grandmaster Flash standing on the top. That was a sought-after item. Virgil did his take on the DJ box in his first season at Louis Vuitton menswear in another interesting way.

Nike × Tom Sachs NikeCraft Mars Yard 1 (2012)

Tom Sachs did a show about a fictitious mission to Mars at the Park Avenue Armory in New York, and that’s where we launched the collaboration. Tom didn’t want people to just line up and buy the stuff we made for it. He wanted to make them do something physically and mentally demanding, a test of dexterity and endurance. He’s actually quite into keeping fit, so he made this assault course that you had to finish in order to buy the shoes. So we did an event with people literally climbing up a rope and ringing a bell, and we had this remote control helicopter that you had to fly and pick stuff up with. Tom got drill sergeants ordering people to go back and repeat the tasks properly. You became part of a living art installation, but at the end you earned the right to have the shoes.

He really forced us at Nike to mass produce a product while trying to make it look handmade. All while his art was doing the opposite with deliberately non-polished cheap-looking, but very intricate objects like a papier-mâché moon-landing vehicle. It was a fantastic example of collaboration. We would never have come up with this thing on our own. We continue to work with Tom and he continues to try and drive us crazy with his approach, but we always end up with really, really interesting results. This is collaboration on quite a deep level for everyone, including our customers. It’s not just ‘rush here today and get this shoe and put it on eBay’; no, you’ve got to really experience something together to even get the shoe. It’s collaboration as a journey.

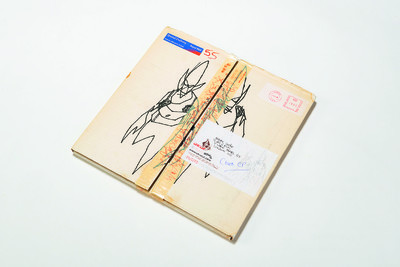

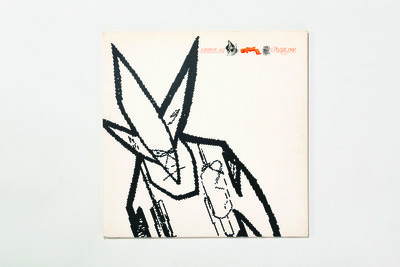

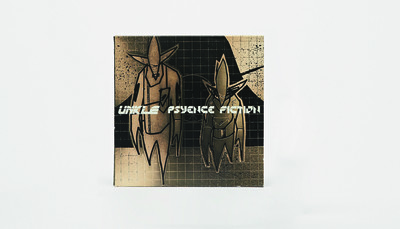

Futura × Mo’Wax × UNKLE (1998-)

James Lavelle and I are long-time friends. I used to be his flatmate and work at Mo’Wax, his label, for a while. When he wanted to do some merchandise like print T-shirts and record bags, I ended up doing them for him. He’s such a good creative director and orchestrator; he just pulls together different elements so well. James was a big fan of Futura’s work and started commissioning him to do paintings for the Mo’Wax label and his own band UNKLE. His Pointman character that he’d been doing for a long time became the band’s symbol. At the time, Futura, who had come out of the original graffiti-based birth of the hip-hop movement, was always super ahead in terms of his art, like an abstract painter really; he was doing stuff with James Nigo and A Bathing Ape. The Beastie Boys were in there, too. This is such a good example of the scene around the Hideout. All these things represent a moment in time. I can’t think of many other music projects that went so far in incorporating everything together. James took it to an almost twisted level; there was art and design and films and physical toys and of course, the records. He was trying to create a complete universe around the band.

Undercover × Levi’s Leather Type I (2017)

The Levi’s Type I is just so iconic; it’s been referenced a million times, because these basic menswear staples always work well. What Jun Takahashi did with it is so interesting – a simple, but just beautiful version made out of really soft lambskin leather, with no graphics, but with a slightly off-centre zip. He also did versions of the Type II and a Type III, and a Type I with lyrics from the German band Can printed on it. The Type II was extended at the bottom to make it into a chore jacket, which was an interesting way to play with shape. It’s very clear what the base of it is, but he morphed it into something else without taking it too far. Sacai also worked with Levi’s jackets, but they took it much further, by deconstructing and messing around with them, as did Junya Watanabe. But I still always like the jacket as it is, the original.

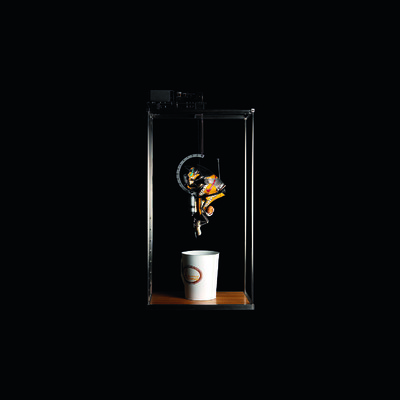

White Dunk × 25 Japanese artists (2003)

Back in 2003, we did this touring exhibition, White Dunk, that began at the Palais de Tokyo here in Paris, and then moved to Tokyo where we housed it in a building constructed to look like a giant shoebox, next to the Prada building. Mark Parker and a Japanese Portland-based retailer and art collector selected 25 Japanese artists, from manga artists to sculptors, and invited them to use the Dunk as a canvas for all this art. We created a lot of content for this, video and books, and we did shoes for each city: Tokyo was a white canvas Dunk, almost like Carhartt canvas but white; Paris was art on a shoe; and though we didn’t do White Dunk in London, we did have a London Dunk, which was grey, because it’s grey there, and had the Thames on it. The shoe was just a starting point. Some of the people really abstracted it to the point where you can’t even tell what it is any more. Some of them really took a direct reference from a basketball shoe. There’s one where the whole thing is a contraption where it literally dunks a doughnut into a coffee cup; it actually worked! White Dunk was about supporting artists and allowing people to have more free expression. It was an amazing, interesting, immersive experience, and a way of bringing a lot of people into the conversation.

Frank Ocean × Tom Sachs, Endless LP launch with Apple Music (2016)

I wanted to also look at collaboration in other ways, beyond just footwear or product. In 2016, Frank Ocean, who’s a really uncompromising artist, released two new albums. One of them, Endless, came with this 45-minute video in which he’s building a ladder to nowhere in the artist Tom Sachs’ New York studio. You watch this thing happening in the film as you listen to the album, which is amazing. I think he’s really the artist of his generation. The collaboration was interesting because Frank and Tom genuinely know and like each other, and it was just such a disruptive and different way to release a record. You could only get it at that time, and the visuals were weird, quite boring in some ways and hard to watch. It forced you to be a little bit uncomfortable, which is what good things tend to do.

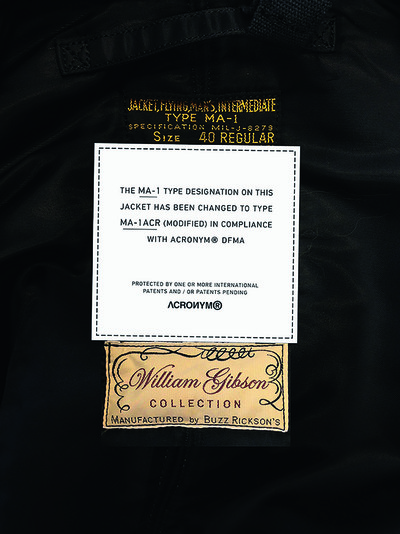

ACRONYM × Buzz Rickson’s MA-1ACR (MODIFIED) jacket (unreleased prototype)

This is a nerdy one. Buzz Rickson’s is a Japanese company that does amazing reproductions. Whoever runs it has a crazy archive of vintage Japanese and American World War II and beyond military stuff, and they’re reproducing it down to the zips and exact thread counts. Errolson Hugh of ACRONYM, who I’ve been working with for years, became involved with Buzz Rickson’s because he’s friends with the writer William Gibson and in Gibson’s book Pattern Recognition, the main character, Cayce, has a fictional black Buzz Rickson’s MA-1 jacket. The company decided to make it because Gibson wrote about it – it became a reality afterwards. Errolson was excited about doing this jacket because he’s done various takes on MA-1s, just like every street-level men’s designer, but he always felt that he could improve upon it. His design process is to start from scratch and build a pattern around the objective. Form follows function, literally. But this thing already existed so he was wondering, ‘How can I take something but improve it?’ I’ve never seen this jacket in person because there are only two samples in existence. He has the one that’s in the above photo (that’s Errolson in his Berlin studio photographing Hiroshi Fujiwara wearing it) and Buzz Rickson’s has the other. It was never made commercially; Errolson doesn’t know why. Maybe if we show it now, we can make it happen, just like the Gibson version. We can perhaps will it into life!

Sacai x Nike LDV Waffle (2019)

There’s been a tremendous response to these shoes already. It’s classic Sacai, which is about clashing two things together, so sometimes the front is different to the back. When we sat down, Sacai said to our design team, ‘We just want to take two shoes and clash them together.’ Somebody said, ‘OK, you mean something like this?’ And took two pictures of vintage shoes, folded the pages and laid them next to each other. And that’s where it started from. We just worked from there. It’s the LDV Waffle, really old running Nike shoes with a colour palette drawing on that heritage as well. The other shoe in that collection is the Blazer and Dunk mixed, so two basketball shoes smashed together. That absolutely speaks to Nike, but it absolutely speaks to Sacai, and it seems like this is going to be one of the most popular shoes of the year. The LDV Waffle has a double tongue, double logo and double sole. The design team at Nike had fun doing this; it’s a different way of engineering for us. This is the second time we’ve worked on footwear with Sacai, and the results show we’re in sync.

Supreme x Louis Vuitton (2017)

This was the moment when the balance tipped and street and fashion came of age. Nothing validated it more than this collaboration. Kim Jones absolutely comes from a street background, and as creative director of menswear at Louis Vuitton, he always paid homage to things he respected. And Supreme, if you go back, had done a fake LV-esque take on a skateboard; I think they’d had a cease and desist from LV back then. But then they finally did this thing together. It talked to the whole Dapper Dan, New York, fake Gucci, LV uptown style, that whole clash, but now recognized as legitimate. It was the coming-out parade for everything we’d been involved in. It was a long time coming and this was the moment. The current generation of designers has grown up with street, so I think that it feels quite natural for them. People like Riccardo Tisci have brought a street element into high-fashion houses. Without Kim being at Vuitton first, and this collaboration, I don’t think it would make as much sense for someone like Virgil to take over at the helm at Vuitton.

Hermès × Leica M7 (2009)

A collaboration that shows a really good way of adding a layer of premium to an already premium brand. Both brands – one French, one German – are about precision and craftsmanship in their respective field, and together they made a beautiful, timeless, high-end product. They’re both quite restrained. Hermès isn’t wild; it’s not pop in the way that Vuitton can be. It’s about craftsmanship. Leica is all about precision and detail. People don’t realise how much goes into these collaborations. They’re simple to look at, but it’s complex to arrive at this level of functionality. This particular model is the film version – it’s not digital – so it can’t date. They’re bloody expensive to begin with, but this thing’s crazy expensive.

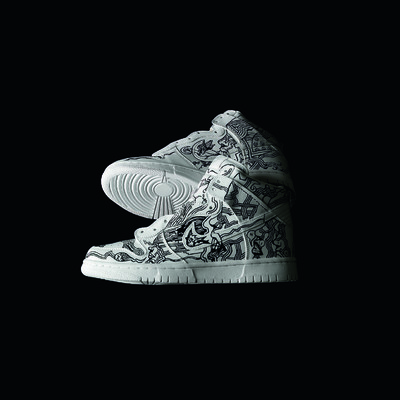

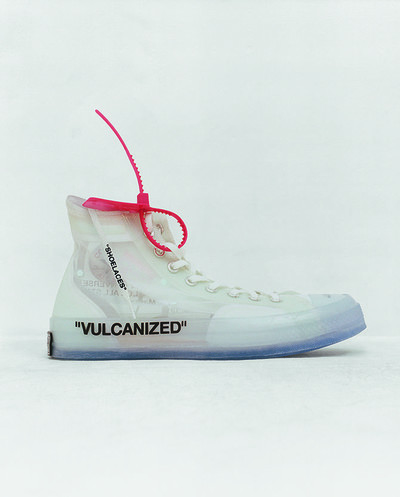

Off-White × Nike (2017-2018)

There’s never been such an industry-changing footwear collaboration as the Ten. It is just so rich with all those classics, shoes that people really love, and some newer silhouettes in the mix. The way that Virgil worked with our team was not to deviate too much from the shoes’ intrinsic design, while at the same time making them distinct. It’s not just the colour or material; there are pattern changes, material changes. The scale and impact of this is similar to Supreme × Vuitton, but different in that it was so much more than just the shoes. It was also special curated talks: Gilles Peterson talking about music and pirate radio with Virgil in London; Spike Lee in New York on a panel talking about Nike and advertising and film; and Virgil talking to Kim Jones at the Barbican, a newer designer talking to a more established designer. It was Virgil giving kids the cheat codes to understand what took him years to figure out. He wants to throw out all this information hopefully to inspire them to be the next generation of really creative kids. For us and Virgil, it was like, here are the products that you all love, but let’s explore and have fun with all this other cultural stuff that led me, Virgil Abloh, to want to be in a position working with Nike on shoes. It was a really rich, virtuous circle.

Shawn Stussy × Carhartt × Tommy Boy staff jacket (1992)

Carhartt and Stüssy released a jacket for Dover Street Market in January this year, which is based on this one from over 25 years ago. Not the same colour, but the same shape, a staff jacket. Shawn Stussy’s not involved with Stüssy anymore, but back then he was putting together the original International Stüssy Tribe, a group of DJs and people involved in sub-cultures like skate. It was a loose collective across New York, London and Tokyo. The story goes that one of the original Tribe members Albee Ragusa worked at Tommy Boy records and asked Shawn if he could do a special jacket for them. I have one; it’s really faded now, almost white, because all the brown has washed out of it. Back then, it was an early example of friends collaborating on something. Today, it’s a genuine streetwear artefact.

Bearbrick World Wide Tour (2007)

This is a good one because such an incredible list of artists took part using this basic thing. Bearbricks aren’t that unexpected or surprising these days, but there was a moment when they were highly sought after, and really symbolized the time. They became this completely mad canvas to paint on for so many different people. An amazing list of names produced so much and made so many variations. Nike supported the Bearbrick World Wide Tour and toured it a little bit. The show touched a lot of people. Bearbricks were often quite cheap initially, but some of them are now worth a lot of money. It was a fun, creative exercise that rolled along because different artists were added as it went. If Warhol were around he’d totally get this sort of thing: it’s a useless object; it does nothing for you; you don’t need it; you can’t wear it; it’s just decoration. This was collaboration for the sake of collaboration, which in itself is interesting as an idea. That company has had tremendous success with this one cute bear character that continues to take on so many different appearances.

Electric Cottage × Vestax, mixer (1997)

Before Fragment, Hiroshi Fujiwara used to have a brand and design project called Electric Cottage, and he would DJ really well. This object is still culturally relevant to streetwear people. The Vestax collaboration was around the same time as the Motorola StarTAC phone [launched in 1996]. It was this little flip phone, really small, but it was a cool one to have because it had a distinct design. At the time, there was this whole transparent skeleton vibe. There were transparent pagers and transparent Palm Pilot devices. I remember Hiroshi managed to get a transparent third-party case for his Star-TAC. Virgil, too, has recently collaborated on mixers and CDJs, with Pioneer, born out of a similar thought process. He wasn’t even aware of Hiroshi’s one; I showed it to him and he was like, ‘No way!’ These things aren’t copied; people can arrive at the same thing by chance. And, you know, Virgil has always DJ-ed: there’s that great photo of him as a 17-year-old in his bedroom DJ-ing. He did a party in Paris the other night and was the first one there, he couldn’t wait to get on the decks!