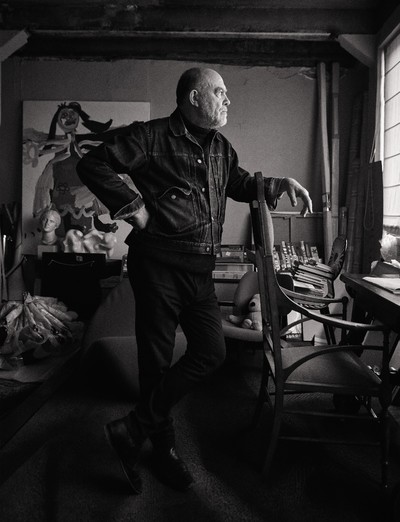

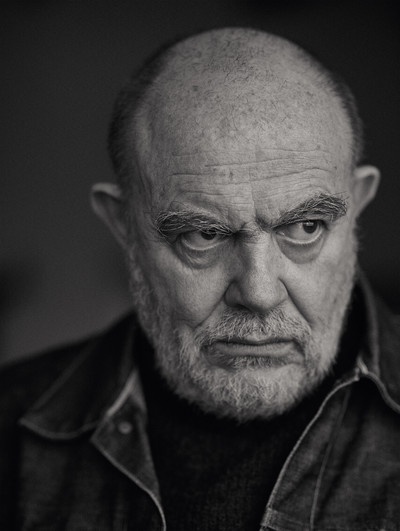

Christian Lacroix’s designs looked like the fashion you would imagine if you had only ever imagined it.

By Tim Blanks

Portraits by Dominique Issermann

Christian Lacroix’s designs looked like the fashion you would imagine if you had only ever imagined it.

Genius is no guarantee in fashion. You can change the world, but that world eventually, inevitably demands payback. The fashion industry is, after all, a commercial enterprise. So while Christian Lacroix helped define the 1990s, fashion’s golden decade, his business never turned a profit. It’s a demoralising thought that the inspirational ebullience of his work should now be so overshadowed by financial failure. Perhaps it’s simply too soon for posterity to give him his due, to gild him with the reputation his genius demands – but it’s not too soon for me. I was a country boy, and season after season, Lacroix’s shows were my hot-pink-drenched passport to a higher plane. The gourmet spread he laid on backstage was only the start. Lift-off took place with the visual and aural froth of the set and the soundtrack. Then we soared into the stratosphere on clouds of colour, wings of sumptuous fabric, flying carpets of rococo pattern. Christian Lacroix’s designs looked like the fashion you would imagine if you had only ever imagined it. Pure fantasy. And then he’d bring everything back to earth with libertine severity, a jolt of tailored black, a hint of inquisition. He teased. He’d be all tweedy, Ralph Lauren-y backstage, and you wondered where the fantasia came from. I had some idea, but then I spent several hours talking with Lacroix at the Hotel Amour in Montmartre earlier this year and realized that, even after all this time, I’d actually had none.

The Arlesian childhood

Christian Lacroix: As a child, I was a bit fragile and very often ill, and I was always fascinated by the past. I can remember when I realized what the passing of time meant: one day I was at my grandmother’s and she bought me a Mickey Mouse magazine from the newsagent next door. I was in love with Mickey. My dream every morning when I woke up was to see if Mickey was in my bed. I wanted him to be alive; I loved him so much. I imagined Mickey and I attending a film opening

and there were real people mixed with the cartoons. I was excited by seeing the date on the cover of that magazine – 1947, five years before I was born. I understood then that life, the world and Mickey had all existed before me, and in that moment, the past became my thing. I learned that early in the antique world of my grandparents’ house. It had a real attic, with clothes and books. I found bound volumes from the Second Empire, fashion books from 1860, a century earlier. The same year, I saw the trailer of Visconti’s The Leopard at the cinema and it had the same sort of clothes as I’d seen in the books. I thought the past was so amazing, but there weren’t many books on the actual history of fashion. For Christmas one year, I asked for a Swedish book about the history of fashion and then, in the 1960s, the curator of the Musée Carnavalet did a big book, and I spent all my pocket money buying it.

I was always boring my grandparents. Tell me about the family; tell me about the war; tell me when you lost your mansions. On my father’s side, they imported farm equipment. They were quite nouveau riche, but they were elegant; they had taste. They lived in the mountains in the south, in the Cévennes. It was a wonderful house. When it was snowing, they had to leave with the children at five in the morning to get to school for eight. My great-aunt Madeleine was the first to go south to Arles. She was the only one who got her baccalauréat. She was brilliant and wonderful, and my first muse. I could cry when I speak of her. During the war, she was in the Resistance. They had all these Jewish workers with fake names in their factory, and she was arrested by the Gestapo. But it was made up of young guys from Arles and she recognized them. She walked up to one guy – 17 or 18, in a big coat, who had a gun pointing at her – and slapped him in the face, saying, ‘Does your mother know you’re here?’ I never heard this story from Madeleine, only from the family. I know that she also helped a doctor and a very famous surgeon escape from the Germans in Arles by dressing them as women in her clothes. But she would never tell me anything herself. She would just laugh when I asked. Until she died, I was in love with her. She was so elegant, always dressed in Maggy Rouff, an old French couture name, with patent leather high heels, even at the end. Every morning and every night, I have a little tear for her. One of my biggest regrets is I could never tell her I was gay. I introduced all my gay friends and she accepted them because they were my friends, but she would have been different if she had known I was, too. But from the skies, she agrees.

I know that Madeleine had some kind of connection with the people at the Élysées Palace. Her sister, my grandmother, was invited to the Élysées Palace ball during the Universal Exhibition of 1937 in Paris. She actually appeared on television during the Exhibition and she remembered the makeup and how hot it was. She was very coquettish. This was my father’s side of the family. They were opposed to him marrying my mother; they had prepared a bourgeois marriage with a doctor’s daughter. When the Germans invaded Arles, they took over the girls’ school, so my father and mother ended up in the same class. She always said she hated him, because he was too elegant for wartime. She called him Rita, because he was a redhead like Rita Hayworth.

My mother’s family had arrived in Arles in the 17th century. They were originally lacemakers. My mother’s father worked on the railway and he was a total dandy. He had no money, but he wanted all his clothes lined with green silk and his bike painted gold. I don’t know why. I think my first guy attraction was to him. Even in his 60s, he had beautiful muscles. And he was very tough. When I was a child, he would take me into the gypsy area of Arles and tell the kids to beat me up. He wanted me to resist, to make me tough.

‘My mother said she hated my father, because he was too elegant for wartime. She called him Rita, because he was a redhead like Rita Hayworth.’

He didn’t take you to brothels to educate you, did he?

No, not me, but he was visiting them a lot himself; he had a lot of mistresses. Both of my grandfathers were unfaithful to their wives and had mistresses. When my father’s mother died, my grandfather married his mistress who was far older, with too much lipstick and blonde hair. Quite vulgar.

Your father’s aunt Madeleine was involved with the Resistance, but what did your mother’s family do during the war?

My mother’s father was in charge of the trains, and he didn’t do any Resistance work. He never collaborated, though. He was an opera lover, and he was fascinated by the singing of the German

women soldiers. He would follow them and sing with them. He was crazy. Arles was very badly bombed during the war because it was a very important railway junction, but he was too proud to go to the shelter during the bombing. He’d go and hide where the sewer entered the Rhône river and watch the spectacle. The fish were dying because of the bombs and at the end of the alert, he’d collect all the fish. One day when he got home, everything had been destroyed, but he’d organised a dinner for 12 people, so he told my grandmother to make a fire with the furniture so he could cook the fish and still have his dinner party.

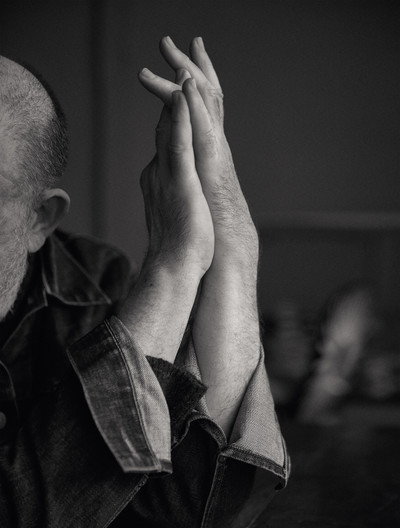

My grandfather was wonderful. He had his beloved bird, a little bird with red and yellow feathers, and it would go down through his shirt and come out through his fly. And every two weeks, he would go to the attic and create a performance out of the news. He would mix terrible things with happy things, making it funny, like a one-man show or stand-up comedy. And he would do this just for my parents and me. My mother was an only child, my father was an only child, and, at the time, I was an only child. He would do this one Sunday, and then the next Sunday, I would imitate him for my father’s side of the family, acting, singing. I was only six or seven, but it was a big influence on me. It showed me that life is interesting when it is like theatre, and fashion is interesting when it was like theatre, but with a populaire side, too. Anything bigger than life. Perhaps I was afraid of reality, and doing anything over the top struck me as a way of protecting myself from it. I think my grandfather was doing the same, laughing with catastrophe. In the end, he went mad because he drank too much. I remember my mother and I taking him to the doctors and he said he’d gone crazy because his mistress – who was a hatmaker – had left him. He was diagnosed with délire de la persecution, and committed to a beautiful 18th-century clinic near Avignon. It was still furnished with 19th-century wallpaper, everything was like a townhouse, and every week, he sent me postcards, photographs of the furniture, and would ask me to please sketch them for the next week. My grandfather loved my

way of sketching – he understood. At the end, he was in the hospital in Arles, in the very room where Van Gogh was kept. I visited him every day because I was the only one in the family he would recognize. He was 77, but he still had those beautiful muscles, and he would smile every morning when I came to shave him. At the end, he was leading my hands. He had wonderful, thick-veined hands, with a ring that a Serbian officer had given him in the First World War. It was always very difficult to leave him. I was 18 then.

The arrival in Paris

It had been my life’s dream to come to Paris since the beginning of the 1960s. I used to tell my parents: I can’t do anything without being in Paris. I was 19 when I arrived in October 1973. But I was so disappointed living here – the smell, the people, everything. The only thing I loved was the sky, because we don’t have the same sky in the south, or the same sunrise or sunset. I went home for the weekend, and when I came back to Paris, I was crying under the shower. If I hadn’t met Françoise [Rosenthiel], I think I would have run away.

It was a Sunday. I called a boyfriend of mine and I told him I was so sad, could I come round for a cup of tea? He had a wonderful studio on the Rue d’Assas, very elegant, in the sixth arrondissement. After 10 minutes, this girl arrived with a great shirt and ethnic skirt, her mother’s old fur coat from the 1930s, white stockings, and navy and black platform shoes from Durer, a very famous shoemaker at the time. And she had a Vidal Sassoon haircut. She’d go to London to have her hair done. She was ‘wow!’, with this smoky voice. I fell in love at once.

The Parisian life

At the time, Lacroix was working on a dissertation on dress in 18th-century French painting at the Sorbonne, and had enrolled in a programme in museum studies at the École du Louvre, one of France’s most prestigious universities for art history and archaeology. He waited until 1989 to marry Françoise. ‘When I signed with Arnault, I had to travel a lot,’ he recalls, ‘and if something happened when I was flying, I had to protect her.’

You came to Paris to be a fashion curator. What made you want that?

The past. Living in Arles was like living in a museum – the past was so much more important than the future. I only became really aware of the future in the year 2000. Before that, I was only interested in the past; I was afraid of the present and didn’t care about the future. My work was always speaking about museums, never inventing new things. It was just the matter of remaking the old. I was inspired by something Goethe said about how the future is the past revisited from the present, that we can’t build the future without stopping by the past. That was my motto. At the time, there was no museum of fashion: the Galliera was closed; the Musée de la Mode didn’t exist yet. So I was preparing to become a fashion curator without a fashion museum. I was in love with the Victoria & Albert Museum in London; my dream was to be at the V&A.

So what were you going to do with this qualification?

I was just trying to please my parents, to have a little bit of money, to be in Paris – and it was exciting. I had the most exciting teacher at the Sorbonne. Monsieur Thuillier was a specialist in Poussin and Caravaggio, and the courses were like, ‘Wow!’ At the École du Louvre, we had all the Louvre curators as teachers. I could have been a student forever; I loved listening to brilliant and bright people. Subconsciously, I knew I would never be a curator, but I trusted my tutors. I didn’t know what my future would be, but I thought maybe as a fashion illustrator, not as a designer. When I arrived at the Sorbonne, I told Monsieur Thuillier that I wanted to do something about how fashion was always inspired by the past, how there was nothing new: Charles Worth inspired by the 17th and 18th centuries; Paul Poiret looking back at the First Empire; Elsa Schiaparelli inspired by Napoleon III; Dior inspired by the turn of the century; and Saint Laurent inspired by the 1940s. I had seen this as a process that took about 30 years, but my professor looked at me like he didn’t really understand. He said, ‘I would much prefer you to do something about the colour in Italian paintings of the 17th century.’ Poor me. I didn’t do it; that’s why I’m not a curator.

‘I had girlfriends and boyfriends at the same time, but I never separated them. I always told girls I was with a guy and I’d say to boys I was with a girl.’

So how did you make the jump to actually making clothes? Did Françoise help you?

I was more and more bored by my studies. I was studying at the Louvre and the Sorbonne because I was supposed to do this competition that museums in France do every year to find new curators. I did it, but I didn’t win. I was upset because I was used to being first. If ever I were second at school, my parents would punish me. It was easy in Arles, but not in Paris! So I took it as a sign. Then a friend of Françoise’s saw my sketches and she said, ‘You’re complaining that your history of art courses are boring? Are you crazy? You’re made for fashion!’ She sent me to Marie Rucki at Studio Berçot. Forty years ago, she was the queen. She looked at my things and said, ‘You’re too old for my school, but I’ll put you in touch with designers. I’ll write some letters for you to Marc Bohan, Angelo Tarlazzi, Pierre Bergé, Karl Lagerfeld.’ At the time, it was so easy, you could just call Karl’s secretary, and she would say, ‘Sure, how about next week?’ And Karl would spend the afternoon with you if he liked your book. I wasn’t thinking about fashion, though; I was thinking about costume design. Françoise and I were buying vintage things from flea markets or fabric offcuts from Vionnet and Schiaparelli at this wonderful boutique on Rue du Bac. I wanted to do something in movies, with my knowledge of all the period costume. Karl was very helpful because he felt that I was much more a costume maker than fashion designer. He sent me a lot of letters over the following weeks, recommending me to people in the theatre. But it didn’t work. Then Françoise’s friend, the one who sent me to Berçot to begin with, told us about Jean-Jacques Picart, a friend of hers who was starting out in PR and was in charge of Mugler and Montana. So Françoise met with him and went to work with him. She was responsible for Guy Paulin and Popy Moreni.

The first job I had when I joined Jean-Jacques’s office in 1978 was to organize Helmut Lang’s first show, in Vienna. I was in charge of getting the models, all the top girls of the time. The only one who didn’t make it was Mounia, who missed the flight, at six in the morning. The show was at the Palais Trautson and it was very Mugler-inspired, with skirts opening with zips, a fan of colourful fabric. Helmut Lang and I fell in love a little bit. We were close for years because we were living on Rue

des Beaux Arts and he was at the Hôtel des Beaux Arts. We had the most spirited Christmas relationship – he gave me the most amazing things for Christmas, very simple but remarkable.

That was just when Picart had agreed to become a consultant for Hermès. Jean-Louis Dumas had taken over and he wanted to change everything. He hired Madame de Vésian, a very tough aristocratic lady from outside the house, and she needed an assistant. Jean-Jacques told Françoise and me that there were two positions, one with him in PR and the other with Madame de Vésian. Françoise said, ‘I’d much prefer to work with Guy Paulin, and you’d prefer to work with girls.’ And that is how I started as a designer, in 1979. I learned everything about designing a collection from Madame de Vésian.

In January 1980, Lacroix left Hermès and began designing accessories for Guy Paulin. When Paulin took over from Gianni Versace at Byblos, Lacroix became responsible for accessories in both collections.

I spent two years with Guy. Jean-Jacques Picart was also a consultant for Jun Ashida, the Japanese couturier who designed for the Empress. He needed some advice, so I was also doing capsule collections for him. I had such beautiful materials to work with. That was the first time I did my own outfits. Then, on a flight back from Tokyo, Monsieur Picart told me the house of Jean Patou was looking for a designer and, because of my success at Hermès, he was going to show them my book. I was the youngest, the least known and therefore the cheapest, so they asked to see me at Patou. It was over anyway with Guy Paulin because he was having problems with the Girombelli family at Byblos. I had all the accessories I’d done for Guy, I added some pieces from Ashida, and some looks from a year of freelancing in Italy, so I had things to show. Jean-Jacques had launched Inès de la Fressange during a Cacharel show, and we’d become friends, so she agreed to model my looks for the Patou family. Just Jean-Jacques and her alone; I didn’t attend. Then they asked to meet with me, and I was hired in January 1982.

‘The first job I had when I joined Jean-Jacques Picart’s PR office in 1978 was to organize Helmut Lang’s first show, at the Palais Trautson in Vienna.’

The Jean Patou years

It was like a movie. There were rumours that Roy Gonzales, the former designer, had tried to kill himself in the studio in November or December. When I arrived at Patou, I discovered a photograph of a young Karl Lagerfeld with a model. He had been at Patou from 1957 to 1964, and there is a famous picture of him sitting at a table in a high chair with a model looking at an engraving on the wall. I had the same table, the same chair, the same engraving as Karl Lagerfeld. Jean Patou had died in 1936, but his office had never been changed, not even the carpet. I loved that. The studio was in a wonderful 18th-century building in the Rue Saint-Florentin. Have you ever seen the French movie from the 1940s called Falbalas? It’s a favourite of Jean Paul Gaultier’s and mine. It takes place during the couture shows, and we knew that atmosphere. Jean Paul worked at Patou as well, as an assistant to Angelo Tarlazzi.

My first show at Patou was a drama. I had no sense of a budget and I thought I would love to have an atmosphere – Morocco, the 18th century, blah blah blah. I showed a group of each, and then a little bit of everything at the end. The following day, Le Quotidien de Paris, which was a well-read paper at the time, said the collection looked like it was done by the coursier, the delivery guy. For the second collection, I decided to be choosier. I used just two colours, red and black. The morning after that show, Le Quotidien was raving. From that day, the Patou family was very supportive. The third collection for Spring/Summer 1983 was all naive hand-painting, with big hats. It was the first time I dared to be me. The Patou family pushed me out onto the runway; I was crying, holding flowers.

I wasn’t there to express my own ideas; I was there to express Patou. I loved that – it was like doing a movie. I was still in my theatre thing; I was not a fashion designer. It was like Cecil Beaton doing the costumes for that musical about Chanel with Katherine Hepburn. Doing fashion, but for a movie. You had Montana and Mugler doing ready-to-wear at the time, with the inspiration coming from Hollywood. I thought we gave it more meaning doing it in couture, because all this movie stuff was much more couture than ready-to-wear. But a lot of people stopped talking to Jean-Jacques – they didn’t know who I was – because he was working at Patou. They felt he was a traitor, that he had been supporting the new créateurs like Montana and Mugler, so what was he doing with this dying old lady of haute couture?

For each collection, we made a videotape for customers, with a little bit of production. At the beginning of the tape for my third season is Inès arriving for the show. Her grandmother, now very old but very elegant, had been the wife of a famous minister before the war. And on the tape, Inès is showing her grandmother a picture of herself in a look from Karl’s very first couture collection for Chanel. It was a nice moment. Karl understood that couture was something that could belong to the future.

For each collection, I defined a connection between Monsieur Patou and me. A famous French caricaturist from the 1920s called Sem drew a cartoon of Patou at a bullfight in Biarritz, and this spoke to me. This was kind of an homage to my father, doing something about bullfighting. People felt that subconsciously it was my roots. At the time, the models were so crazy. I gave Anna Bayle a tape of Carmen Jones to show her what a bullfight looked like, and she showed up at fittings with Betty Lago, the brunette from Brazil. I had so many sketches I was mixing together – the dresses were different at the front than the back. Anna understood this perfectly, because she was going out first. Hebe Dorsey from the Herald Tribune and John Fairchild from Women’s Wear Daily came and raved.

‘My first Patou show was a drama. The next day, Le Quotidien de Paris said the collection looked like it was done by the coursier, the delivery guy.’

That was later. Who supported you from the start?

Suzy Menkes was aware from the beginning, and I loved Carrie Donovan from the New York Times. She came one day, I didn’t know who she was. She asked what my favourite piece was; it was very

baroque, with Lesage embroidery on the front. Ahn Duong was our house model at the time and they took a picture of her on the balcony wearing it. It took five minutes. Then they left and I forgot about it. I don’t know how many weeks later, it showed up as a double page in the Times magazine. When the Patou family went to New York to launch a new perfume, Carrie invited us to lunch at the New York Times’ dining room. The family was so boring, and before dessert arrived, she said, ‘I’m sorry, I’m in a hurry, I have to take Christian.’ We left and spent the afternoon with Donna Karan, who was very welcoming. I adored what she was doing.

So this was all before the pouf skirt sensation?

No, the very first pouf skirt was in the very first Patou collection in 1981. Before I was hired by Patou, I was in a hotel room waiting for Françoise and working on a collage. There were some fashion engravings from the late 19th century in Figaro magazine and I cut the dresses short and added my favourite black-stockinged legs. And then, because I was hired at the very last minute by Patou, I had to use everything I had, including that collage. So my first mini-skirt was inspired by that. It was like a bee, black and yellow stripes, very short.

But nobody said anything about a new silhouette?

Nobody saw it. And I didn’t do any in the second collection.

I remember there was always the controversy about the pouf skirt and Vivienne Westwood and her mini-crini.

They’re arriving at the same time, yes. I became aware of that later. But it’s like, ‘Who invented photography, the English guy or the French guy?’ I think each generation has the same universe, just in different countries.

Were you friends with Vivienne?

Of course! It’s been a long time since we’ve seen each other, but in 1991, John Fairchild asked me to choose one designer from Italy, one designer from Great Britain, and one from the States for a fashion summit in Japan. So I chose Franco Moschino, Isaac Mizrahi and Vivienne, and we spent weeks in Japan. It was a wonderful time, very warm, very supportive. Each night, one of us would organize a party for the others.

I’m trying to pin down which collection it was when the pouf exploded.

We had one very successful collection, with a dress on Anh Duong. She wore a Chinese hat. 1985? 1986? It was on the cover of W, the issue that celebrated the Statue of Liberty’s anniversary. This is when Hebe Dorsey fell in love with the house. She was very ill with cancer, but she did a lot to introduce me to the States.

When I was starting to be bored at Patou, and a friend set up a lunch at Caviar Kaspia with Colombe Nicholas, Dior’s chairwoman in New York, and she said, ‘Why not meet Bernard Arnault, the young guy who just bought Dior?’ So she set up a lunch with Monsieur Arnault in December 1986 at Le Bristol. I was absorbed in my dislike for the Patou collection I was trying to finish, and he was going skiing with his children, and finally he said, ‘I have to go, what would you like?’ And I said, ‘A couture house with ready-to-wear, jeans, perfume and accessories. I don’t care if my name’s on it, but I want something that goes from very deluxe to very affordable.’ And he said, ‘OK.’

At the time, I was still working with Ashida in Tokyo, so I went to Japan just before the January collections, and Hebe called me to say, ‘I think Mr Arnault is very much thinking about your meeting and if I have any advice, it is to get a very good lawyer. I know one, he’s Johnny Halliday and Catherine Deneuve’s lawyer.’ So I met with this guy and we signed an agreement and the day before the Patou collection, I met with Mr Arnault, who said, ‘We sign next week.’ It was still Financière Agache, it wasn’t yet LVMH. But he had Dior and I think he wanted to prove that he was able to launch a new couture house. It was a challenge.

So the day before the show, I was under the table calling Hebe and John Fairchild. I knew I’d be leaving the day of the show. I was even thinking of taking my suitcases and walking off the end of catwalk with them. I was so excited! When Monsieur Arnault was sure, I called Patou’s chairman Monsieur de Moüy in Corsica and told him I had something to say, but not on the phone. We had breakfast the next morning, a Saturday, in Paris and I told him all about Monsieur Arnault and he said that was wonderful, and he hoped I’d do my fragrance with him. But when I arrived at Patou on Monday, he was very upset. And my last vision of the house was São Schlumberger, a huge client who bought half the collection. They delivered what she bought, but stopped everything else, including the amazing ad campaign that Sarah Moon had done. And then there was a very large lawsuit, which they won. The fine was 10 million French francs. I didn’t know I was so special, but they said they launched me, made me famous.

‘Bernard Arnault asked, “What would you like?”And I said, “A couture house with ready-to-wear, jeans, perfume and accessories.” And he said, OK.’

La maison Christian Lacroix

In April 1987, the house of Christian Lacroix opened at 73 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris’s eighth arrondissement.

Dawn Mello at Bergdorf Goodman did an enormous job, because she brought Lacroix to New York. And Blaine Trump. I love her, I still see her. We go to the same hotel in Barcelona. I remember my first meeting with all those beautiful, bored young women, the Ladies Who Lunch; I asked to go to the loo and I went down a corridor lined with Matisse paintings. It was unbelievable! We showed downtown, under the World Trade Center. They bought palm trees from Santa Fe for the Winter Garden; it was crushed in 9/11.

That first show was the event Julie Baumgold wrote about in New York magazine, a week after the financial crash in October 1987. It had the subtitle, ‘Lacroix’s Crash Chic’, and the title on the cover was ‘Dancing on the Lip of the Volcano’ – which is one of my favourites ever. Have you read that story recently? It’s as if someone wrote a story about Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution.

I wasn’t conscious of it being like that. Well, sometimes, not every day. But Julie was good, she told everything just the way it was, not to be mean. I was dancing on the volcano. I remember that night with girls and guys telling me, ‘You’re going to be a star’; while at the same time, others were saying, ‘My husband’s associate jumped out his window last week.’ Being part of a very large New York event, it was something. On my table was Hebe, and Bianca Jagger wearing black gloves, and Blaine and Robert Trump, and Donald and Ivana, because she was a very faithful customer starting at Patou. Donald said, Congratulations, it’s a big hit! Blah blah blah.

That New York cover showed you with Marie Seznec as your bride at the end of the show. She was such a big part of your story. When did you meet her?

I met Marie through Françoise and Éric Bergère, who was interning with Françoise at Hermès. We shared a flat with him, and he later took over from me at Ashida. She was a student at Berçot and she had had some pictures in Elle because she had white hair – which was very rare at the time – and the most beautiful husband ever. He was in charge of menswear for Mugler during Thierry’s time. Marie was starting to do a few fittings for Éric and Françoise at Hermès, but she was looking for some more work, so I hired her as an intern model at Patou in 1984, 1985. She was very helpful for the white-haired customers. In those days, we had to have a show twice a week in the salon. It was a Chambre Syndicale law that doesn’t exist anymore. Six models, every week, for the six months of each season. By the end, it was only old ladies who were attending.

I thought it was audacious of you to make Marie the face of Patou, and, later, Lacroix. It was daring to have a woman who was so different to everyone else in fashion.

Everything different is the way to move forward. We are not here to give people what they already like, but what they don’t know they like yet. Whoever said that, it’s one of my mottos. I worked outside fashion; I never felt that I worked inside the fashion world. When it was the time of the top models in the 1990s, I didn’t do any of that. I worked only once with Linda Evangelista; she was too impressive, too monumental. Carla Bruni, yes, Naomi Campbell, yes, even though she was so difficult to work with. But I was in love with Christy Turlington, and Yasmeen Ghauri, though she smelled of garlic – we both smelled of garlic.

‘We had to have a show twice a week in the salon. It was an old Chambre Syndicale law: six models, every week, for the six months of each season.’

Indulge me while I steal a leaf from Julie Baumgold’s article: ‘the clothes are shocking. They are violations. They break every mother’s Rule of Good Taste: Don’t let your slip stick out, don’t wear orange and purple, don’t wear pink and red, don’t mix plaids and stripes or checks and stripes, don’t be too fancy, don’t overdo. They are just the way every six-year-old girl wants to dress before her mother gets hold of her with the Rules of Good Taste. His colors burst out. They are perverse. They are revolutionary and funny. Straw flowers. A dress that is all slip, mini-poufs, huge panniers, bows and black lace hanging all over, clothes standing out from the body, heart-shaped bustiers thick with flowers and beads, fuchsia shoes, and orange ruched crinolines. On the head, straw platters, straw cache-chignons, straw thimbles with a rose sticking out the top; green satin bags with branch handles.’ That show was the beginning of Lacroix’s eight-year relationship, one that was eccentric, wondrous but ultimately testing. From Arnault’s perspective, it was his opportunity to prove that he could defy tradition and create an haute-couture house from scratch. You could almost imagine him as a Medici-like patron, except for one problem – the Lacroix business became a money pit.

The Arnault experience

Are you still in touch with Monsieur Arnault?

A French journalist interviewed me and later interviewed him, and she asked, ‘Would you like to have lunch with Christian?’ and he said, ‘Of course, with pleasure.’ Monsieur Arnault was very supportive at the beginning. I like him, I love him.

I have vivid memories of how unhappy you were sometimes, though. You complained how the Arnaults would go to Ozwald Boateng’s men’s collections for Givenchy, but they would never come to yours. What was the problem?

I think Monsieur Arnault was very disappointed with the unsuccessful sales of C’est la Vie, my perfume – he wanted a return on his investment in the couture house. Because my fragrance was

made and sold by Dior Perfumes, everyone who sold those perfumes ordered a big amount. The fragrance itself was really wonderful. I wanted Garouste and Bonetti, who made the furniture for my shop, to do the packaging, but it was too expensive, so they were fired. What LVMH did was not so bad: the shape of the bottle was inspired by a stone from the plain around Arles. Mythology says Hercules put the stones there. I collect them. The cap was coral, which was my lucky charm. Someone said it looked like a heart with arteries sticking out the top, and in France, they wrote how disgusting that was. It was hard to get people to buy it, especially because I wasn’t so well-known. In LA, New York, Milan, yes, but in Scandinavia, no. I was just famous in fashion.

Lacroix’s last couture collection for his house at LVMH was Spring 2005. ‘If life in fashion were fair, Christian Lacroix would be awarded a grace under pressure medal for turning out his extraordinary spring haute couture collection,’ Sarah Mower wrote for Style.com. His name was acquired from LVMH by Leon, Jerome and Simon Falic, Florida-based brothers who made their money in duty-free retail.

At the very beginning, they provided me with money, with people. I didn’t have a real financial chairman; they hired a girl from Chanel.

You had been losing money, and you were tired of losing money. You have no bad feelings against Arnault? It was just what happened.

In some ways, it was my fault; I was in a bad position at a bad moment. I was not able to be my own promoter, as an American designer does, like when Donna [Karan] came with her own suitcase and showed her things. I was never able to do this. If I am forced I can do it very well, but it was not in my nature when it was needed. I much prefer to be with my friends than promoting the label. Peter Lindbergh was in love, almost crazy about one of my friends. He lived in Arles; he brought all the top models to Arles in the 1990s, but he never photographed for me! I much preferred having Peter as a friend, to be drinking with him and not using his relationship with Linda [Evangelista] for doing whatever. I was too shy or… I don’t know what. But I didn’t understand that at the time, so it is my fault!

In 2008, Lacroix was guest artistic director of the Rencontres d’Arles, the renowned photography festival, and curated a large-scale exhibition in the city’s Musée Réattu.

I was in charge of so many photography exhibitions and I also did a show at the Musée Réattu, one of the museums from my childhood. I had Old Masters and 18th-century paintings meeting the contemporary art of my friends. The exhibition was extended until the end of the year and people were still queuing during the holidays. I loved doing it, the carte blanche, the total freedom. This was in 2008. I was busy, I wasn’t really conscious that the end of Lacroix was coming. We closed in July 2009. I was sad for all the workers, but it was really a relief.

‘Arnault was very disappointed with the unsuccessful sales of my perfume C’est la Vie – he wanted a return on his investment in the couture house.’

Would you describe yourself as fragile?

Yes, I think so. I survived; I’m a Taurus. I face big things, but I’m destroyed by little things. I didn’t understand the fashion world. The It bag? This was not talking to me. Fashion is something helping you in life, something for your self-expression, to make you feel secure. I stopped being interested when it became these big groups. Now there is nothing in fashion weeks. It is all about advertising and nobody can write anything sincere, or it’s between the lines. I loved Karl as a human being, he was such a brain, but some of his collections for Chanel were… well, nobody wore that, because they couldn’t! The gap gets wider and wider each season between the runway and real life, even in the upper levels of society. Now everyone is so aware of the scrutiny; they can’t take any risks any more. For me, the question is: is fashion a way to be like your neighbour or is it a way of being yourself, different from your neighbour? Nothing is ugly nowadays. If you look at everyone’s Instagram accounts, there is beautiful food, beautiful flowers, beautiful muscles… everything is too beautiful. Bring back ugliness! Baudelaire said there is no beauty without something bizarre.

The (un)holy extravagance of Lacroix’s collections demands sympathetic institutions for its preservation. That wildly successful exhibition he curated at the Musée Réattu the year before his company closed, with its Old Masters and contemporary art, was a lesson in the power of the archive. Lacroix calls himself a hoarder, but unfortunately he never kept much of his own work. He has passed his favourite pieces on to the V&A, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and the Kyoto Costume Institute.

I was not so conscious, except for a couple of outfits. Like the wedding dress made from the red bullfighter’s cape [haute couture, Autumn/Winter 2002]. Madonna wore it, but that’s not why it’s my favourite. That was a hard season; we had no money; we couldn’t afford expensive models. A friend gifted me this cape. I redyed it, Lesage embroidered it. My other favourite was another wedding dress, the very last number of the very last show [haute couture, Autumn/Winter 2009]. Again, we had no money. The Falics didn’t want me to show, so they gave me not a euro. I fought to have this collection, and I succeeded in doing it with old materials and everyone’s friendship. All the agencies were so kind; they knew it was the last show, so we had all the most famous girls for free. The seamstresses, the shoemakers, the jewellers worked for nothing. We had the decor for free. But that dress isn’t my favourite because it’s the last. I loved it because it looked like an icon – I was inspired by Anna Karenina, and Vlada, one of the young Russian girls, wore it. I felt very guilty about not crying at the last collection, not to be part of the sorrow. Everyone else – the models, my friends – was crying. But for me, it was the beginning of a new life.

I’d been discussing my archives with the Falics, but then everything stopped, and now I don’t know where the archives are. They escaped. They were in the suburbs, but we discovered recently they had been moved somewhere. But we don’t know where. It’s very tricky. They agreed when the Met asked for the last bride and the top with the Lesage-embroidered cross from Anna Wintour’s first Vogue cover [for 2018’s Heavenly Bodies exhibition], but if anybody asks for some pieces and they think I am behind it, they refuse. We’re still in a lawsuit; it’s been very expensive for me, but I want to win. I would like to have my name back – and my collections.

Lacroix needs some lace for his new theatrical endeavour, designing the costumes for director Michel Fau’s production at the Opéra Comique of Adolphe Adam’s 1836 operetta, Le Postillon de Lonjumeau. The Algerian man who used to provide him with beautiful lace from China has closed down so after he’s seen me into my car at the Hotel Amour, he’s going to hunt for a new source in Montmartre. He’ll soon begin work on Brecht’s Galileo at the Comédie-Française for Éric Ruf and, in November, an audacious production of The Marriage of Figaro for US movie director James Gray at the Los Angeles Opera. He’s busy.

He also tells me that he feels most comfortable now in Barcelona, where the queer scene reminds him of the polymorphous Aquarian ideal of his teenage years in the late 1960s. ‘If I met up on a street corner with the child I was,’ Lacroix says, ‘I could say, “I did it!” My only comfort is to think that what I was dreaming of as a child is now happening. I am lucky I get to work with the Comédie-Française and Opéra Garnier, and people are asking for period costumes. The white T-shirt and

black suit is not me. Go to Zara. But I would like to go forward.’

‘I felt very guilty about not crying at the last show. Everyone else – the models, my friends – was in tears. But for me, it was the beginning of a new life.’

Will you ever come back to fashion?

Sometimes I dream of being back in fashion, but not with my name. But no, no more fashion. I am very happy. Last autumn, I did a book with Gallimard, illustrating Madame de La Fayette’s La Princesse de Clèves, which is the first real French novel, from the 16th century. I wanted it to be a turning point because I wanted to experiment with new mediums. I did ceramics, old paintings, lithographs. This is a question I had as a child. Am I painter or not? I don’t think so. But my guts, my enthusiasm, is doing paintings today. Creating something. Escaping from anything.

I had a lover at the beginning of the 1970s, a wonderful guy, Michel, who died from AIDS. The last time I saw him was at the perfume launch for C’est la Vie in the 1990s. It was just the two of us at six in the morning, at the party. We had not been lovers for ages, but still we were very close. I introduced all my lovers from before to Françoise and thank God we all became friends. Michel was the same colour as the marble of the walls. And I said, ‘You must do some tests’, but he didn’t want to. He didn’t want to know. And then one month later he died. Later, his family and I chose to do a documentary about him. They had the idea of putting some paintings in this documentary. They asked me to sketch on the wall of his house, which was about to be sold. And after they said that, I was drawing in a different way. I felt like my pen was connected by a ribbon to him. I sketched like I never did before, so different, so inspired, so strong. It was coming from elsewhere. I discovered myself as a painter that very day. Then later I did some big canvases and I was trying to capture his body. He was there.

How long ago was that?

Four months ago. I feel painting is perhaps something I have to do. But I must say that the theatre part of my life is most important to me, because of my grandfather. I said it before: I am afraid of life.

Real life?

Real life, I think so. Two weeks ago, I had a dream I was in a New York hotel and Blaine Trump was there, showing me some golden patchworks she wanted me to make into a special outfit. And I was

supposed to have a photo taken wearing a bullfighter’s cape with her! This is the first year I’ve had dreams about my old job. It was a relief when it ended though. The world had changed so much.