Grace Wales Bonner is tailoring the future of fashion from her own personal heritage.

By Hans Ulrich Obrist

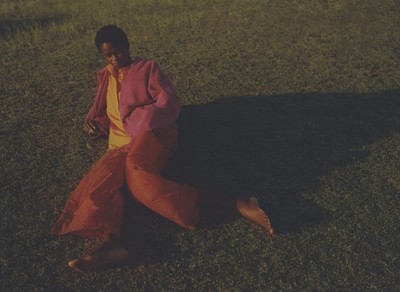

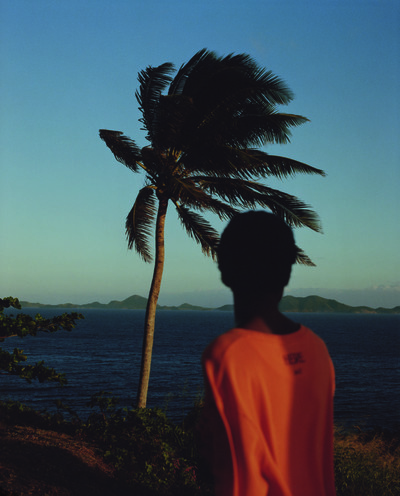

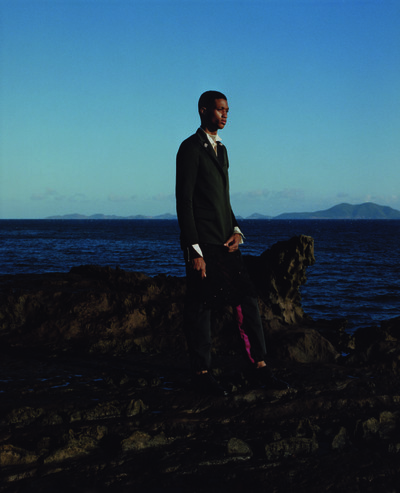

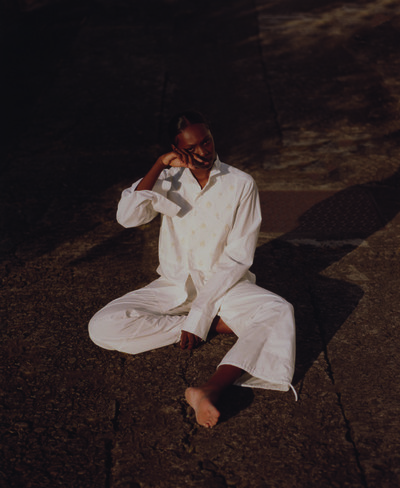

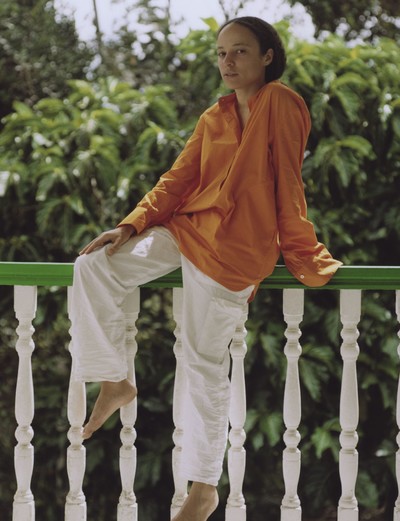

Photographs by Durimel

Grace Wales Bonner is tailoring the future of fashion from her own personal heritage.

Grace Wales Bonner is steadily earning a place in contemporary fashion design’s canon – and the reason is simple: she designs extremely wearable clothes, to which she adds a rich creative exploration of her own Caribbean and British identity, spanning age, gender and ethnicity. The natural convergence of these aspects creates a dynamic that has made her work feel so relevant to today. Since founding her label Wales Bonner in 2014, initially to produce only menswear, she has consistently expressed her personal vision of black male identity, history and culture through an academic, sensitive and poetic lens. And while her rise on the global fashion scene has been rapid – she graduated from Central Saint Martins in 2014, won ‘Emerging Menswear Designer’ at the British Fashion Awards in 2015, and received the LVMH Young Designer Prize in 2016 – she has never allowed that to compromise the technical quality of her precise tailoring.

Wales Bonner is now entering a more considered, nuanced and confident phase of her career, her language now naturally moving beyond the conventional fashion settings of a collection, a show or a campaign. This began with a showcase at the V&A in 2015; her participation in the Transformation Marathon at the Serpentine Galleries the same year; the creation of zines; a creative residency in a remote village in Senegal; collaborations with artists including Sampha, Ishmael Reed, Ben Okri and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye; and a solo exhibition at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery earlier this year. For System, she set out on another visual exploration and collaboration: with twin brothers and photographers Jalan and Jibril Durimel, she travelled to Guadeloupe, shooting a story that represents an emblematic expression of her continuous questioning of identity, place, history, ethnicity and magic. A few weeks before the journey, the Serpentine Galleries’ artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist sat down with Grace Wales Bonner to unravel the roots of her process, her brand’s already rich history, and to take a look into its future.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: How did fashion and art come to you, or how did you come to fashion and art?

Grace Wales Bonner: It was quite a gradual process. I have always been interested in history, identity and representation, which comes a lot through literature and photography, as well as working with archival material. I’ve always been looking to recognize a lineage within images. At school and then at Central Saint Martins, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be an artist or a designer. At Saint Martins, taking the fashion pathway puts you on the spot; if you want to do fashion, you kind of get funnelled immediately into a specific way of working. The pace of it was interesting to me, so I went with that

option. While I have worked with fashion, I have also been nurturing myself with representation and literature. I have found a way to balance those two points of reference and integrate them into my work. Fashion feels like a way I can explore deeper ideas about identity, ancestors, lineage, and connect to different temporalities. I came to realize through studying that by creating imagery and collections, I can communicate in a really immediate way.

What about influences? Who inspires you in fashion?

Coco Chanel. I’m interested in heritage, tradition, and tailoring, and there are a lot of core codes within Chanel that I see as representing the height of French craftsmanship; she has always been an inspiration. Miuccia Prada, also. Just the way she reflects contemporary society like a mirror. She is always responding to the times we live in, in a very deep, soulful, and philosophical way. I think she continues to create really strong collections.

Who else?

In menswear, Raf Simons. His work has been groundbreaking and such an important reference for where fashion is today.

What makes him groundbreaking for you?

The intimacy and the way he engages and grapples with very specific subcultures and can communicate it all in an immediate way. He seems very uncompromising and it is a really beautiful thing to see in this era.

Anyone else?

Craig Green. We crossed over at Saint Martins; his work is incredible. The special thing about London is that people from different generations in the fashion world are very supportive of each other. Kiko Kostadinov’s work is amazing, too; he was in my class at Saint Martins. It is just really exciting to see this kind of energy.

‘My first collection was about finding a group of inspiring men who I felt represented an image of black masculinity that was more familiar to me.’

Samuel Ross?

It’s so impressive how he has navigated the system and just accelerated with such strong convictions. It’s exciting. I think there’s a lot of potential at this time.

And what is it about London with its teachers and mentors? Do you think it is still about the spirit of Saint Martins and Louise Wilson?

I think so, in the sense that the work of the people I just mentioned is very much a product of that education system. It’s what I’m excited about in menswear: there are already established structures in place, so to go into that world and create something new is almost unexpected.

You didn’t study with Louise Wilson like Craig Green, but did you have any mentors?

I had encounters with Louise Wilson at Saint Martins; they were interesting and shaped how I thought about things. But in terms of fashion I don’t know if I have had mentors. I’ve always gravitated towards people from other fields who can inform the way I work; I like to hear from an outside perspective. It’s often a writer or an artist or a musician.

Who were your main inspirations outside the fashion world?

Writers often become the starting point of many things for me, the work of Ben Okri, Kei Miller, Ishmael Reed, Essex Hemphill, and Fred Moten. Or Thelonious Monk, who I think about in the way he deconstructs forms, intonation and scale. I’m often drawn to people who can elegantly disrupt systems, like Ishmael Reed, Ben Okri and Monk, and bring a new sense of rhythm to creation. I think there’s some synchronicity among all these things.

Can we talk about the next beginning, when you left Saint Martins and designed your first collection?

My graduate collection was called Afrique. It explored Blaxploitation and the turning point of black expression in the 1970s, especially in terms of photography and film-making. Ebonics was the first collection after I graduated and was connected to a broader spectrum of representation. I was looking for sensual and beautiful representations of black masculinity across different time frames. I was thinking about the Harlem Renaissance, and the idea of black genius. I was attempting to connect to a deep and rich world, one that linked to many different histories and times. I started working with cowrie shells in the embroideries, so it was also thinking about different ideas of cultural currency and how you integrate these different signifying elements. That collection was starting to explore an idea of hybridity and the meeting point between certain couture and craft techniques.

Can you talk a bit about your early collaborations?

With the first collection, it was about finding boys who were part of my community who could be models. About finding a group of inspiring men who I felt represented the image of black masculinity that was more familiar to me, and which I didn’t feel was being represented in fashion.

So casting was very important?

Totally, and it was very close to the development process. Wilson Oryema, who must have been 17 then, was in the studio the whole time trying things on and telling us how he felt. The way things developed was very organic and conversational. The idea of how I cast was established with that collection really.

That leads us to the second collection in which these collaborations became more marked.

It was called Malik and in it I was exploring the life of Malik Ambar, an Ethiopian slave who moved to India in the 16th century. That was Spring/Summer 2016. That was very much about cross-pollination of worlds, and my reflections on the narrative connections between Africa and India. I was making connections between Nollywood and Bollywood and trying to find links over different times between these places. In that show, which was presented at the ICA in London, I worked with M.J. Harper, a close friend who used to dance with the Alvin Ailey company, and has worked with Wayne McGregor. The first few collections were very much about sampling and referencing different histories, through collage and different literary sources I’d collected for the publications I was working on. This approach was also explored through sound. James William Blades worked on the soundscape interweaving field recordings from my time in Senegal and India along with other historical and found sources. The idea of collaboration became central to how I developed collections. In 2015, I spent a month in a small, remote village in northern Senegal just working on collage. At the end of that, I realized that to create I need to work with other people. Being in isolation doesn’t work for me; that’s not how things happen for me. I was much more proactive after that, reaching out to people I admired and just starting a dialogue.

‘I’m drawn to people like Ishmael Reed, Ben Okri and Thelonious Monk who elegantly disrupt systems and bring a new rhythm to creation.’

So, you had an epiphany in Senegal: you needed to work more with people, in dialogue, as an exchange. Then you came back and created a collection.

That was Spirituals II for Autumn/Winter 2017. Thanks to your introduction, I got in touch with Lynette Yiadom-Boakye who I commissioned to write a text.

You were thinking about the street at the time. I brought you and Lynette together because I felt it was urgent. She is an outstanding artist, but what is much less known is her literature; she is also an amazing short-story writer. She started to write for you about the idea of the street preachers, right?

One of the points to mention is Invisible Man. There’s a moment in the novel when one of the characters is in the street and interacts with people who are gathering – and through his actions he changes the way everyone else interacts. I was thinking about the street and sound in the street, and how that informs the way that people behave, about spaces like Notting Hill Carnival and how sounds in public spaces have transformed communities. I had this body of visual research about street characters over time. It was a broad gathering of people from different eras, from a Renaissance friar to Senegalese street style, but there was a collective style. I showed Lynnette my research and she responded to it, understood what I was talking about, and wrote this incredible text. That was also when I also worked with Elysia Crampton, who created an amazing sound piece which, again, was very much about sampling and referencing different histories. That was a point when I was starting to connect with artists; I was expanding and opening up to the potential of what my work could be. Sampha also contributed to that soundtrack. I was seeing research as a tool to communicate with other artists and to create a broader picture. That has been a tool I’ve continued to use – always having a body of research that I can send to people.

With the next collection, Blue Duets for Spring/Summer 2018, there was an intensity in the relationships between the people in it. Can you talk about M.J. Harper’s choreography of that show?

It’s really interesting working with M.J. because he works out how to express physically the ideas I’m exploring, and he can do very subtle things to express something very important. There is a real tenderness between the characters, and I’m always interested in this softness, sensuality and this gentle way of engaging and being. After that show I spent some time with Sampha in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

That journey to Freetown was important to you.

I went the day after my show, together with Jalan and Jibril Durimel. I often commission other people to create work in relation to my work, but it is also interesting when I have to respond to another artist’s work. In that case, I was responding to Process, Sampha’s incredible album, which won the Mercury Prize. I was thinking about how to visually respond to that album, and so I had this idea of making a publication with the Durimels. I also worked on some collages for Sampha, which used a lot of his found archival imagery from his family. Having access to that and going to where his family is from was a very intimate, close-up process. It was a very important trip for us all. Kahlil Joseph was working on a film for Process as well, so it was a really great time, a meeting point for some really important artists. Seeing Kahlil’s working process was really inspiring, too. Film has always been a part of what I do and how I present collections, but to see it on that scale was really interesting.

‘I have always thought a lot about soulful dressing or emotional dressing, thinking about a real intimacy and closeness to the body.’

There was a moment when some fashion designers started to replace fashion shows with films. But the way you use them is different. How do you connect to films?

I see them as an extension of the research process, one that informs later work and collections. One of the first films I did was with Harley Weir, after the Ebonics collection. We spent some time in Dakar doing a documentary about Senegalese wrestling and spent time with this community of wrestlers. What they do is very physical, and we were trying to represent a tenderness between these men and how certain elements of feminine expression were integrated into how they behaved or even what they wore. I was noticing a lot of men wearing sarongs or women’s swimming costumes, but they didn’t have the same gender stereotypes. They were more like found items appropriated for a different use. I have always been interested in seeing ideas that in my mind are very romanticized and then coming back and filming them in a real place. Then I can see what comes out of that and how it can be developed further. For the Malik collection, we went to Udaipur, Delhi and Gujarat to meet a group of Siddi, an African-Indian community. The whole process is about coming back to a place and examining an idea through a different space. In 2017, I went to Johannesburg and Cape Town with Harley and we worked on a film with a young ballet dancer called Leroy Mokgatle. It was a film about exploring dance in South Africa. Film has been a really important part of my work. It complements the collections, but it is also a really active research process.

The research also gets compressed and summarized in your zines. One of the more recent was with Sampha in Sierra Leone. Tell me about these zines’ role and how you make them.

I see the whole zine as a collage and a way of referencing different voices, history and literature. It’s about collecting all these different narratives together to create this unique world, bringing disparate things together in a dialogue.

You have been inspired by Caribbean modernism and thinking about how that transcribes to an aesthetic end, and that’s become part of your research.

I am very considerate of each place, but I also have a network of people around the world with whom I am in a dialogue. So it is about being responsive and intuitive to your environment and also being

engaged in a wider conversation. I enjoy sincerity and intimacy, and closeness to the process of making. I have always thought a lot about soulful dressing or emotional dressing, thinking about a real closeness to the body, and I think that doing things on my scale, I have a lot more control over that.

About how it is produced? Being a designer with her own successful brand is obviously about creating important and memorable work, but it’s also about maintaining an economy that supports a team structure. Do you see a successful business as about creating a global whole rather than an expression of homogenized globalisation?

I do think it is definitely vital to balance important creative expression with commercial considerations. There is a good support network in London that helps designers develop, but it is still something that I continue to work around and explore.

What would you do if you were to get a phone call from a label offering a great opportunity? Would you ever sell your label or do you want to stay autonomous? Do you want Grace Wales Bonner shops?

I am definitely interested in having my own space and my own store; that is an ambition of mine. I am interested in the idea of an institution and fashion having parameters. A house with heritage is interesting to me, because I am interested in a framework and then disrupting elements of classicism within that. A dream of mine would be to work with a tailoring brand, as that is at the core of what I am doing.

What is your favourite, if you could choose one?

Maybe a brand like Hermès or even a Savile Row tailoring house.

We didn’t talk about the essential collaboration with Dev Hynes.

Dev was involved in Practice, the film that I did in Johannesburg with Harley and Leroy Mokgatle; he composed the soundtrack. He was interested in South African house music, so he was also responding to that. We meet every six months or so, whenever I am in New York or he is in London. But we often cross over in terms of research and ideas and also this idea of gentle masculinity; he really does embody that and I know that collaboration for him is such an ingrained part of his practice. He is so responsive and equipped to collaborate with other people. That is why it is such a pleasure to work with him; it is such a part of what he does every day.

‘A dream of mine would be to work with a brand like Hermès or even a Savile Row tailoring house, as that is at the core of what I am doing.’

Sometimes you also collaborate with the dead, like you did with Gary Fisher, who was a reference for your Spring/Summer 2018 collection. You used his notebooks, which were published in 1994 after his death from AIDS. You said it was the idea of leading a double life like a spy that interested you, the idea that you have to be an infiltrator.

For that, I was talking to Fred Moten, who was at school with Gary Fisher. Fred told me that when the notebooks were revealed it was such a shock because Gary had been such a quiet guy at university. But he had this very complex inner life, which is very interesting. For that collection, Blue Duets, I was thinking about homoerotic literature, but also about a character with a utilitarian job, but who also has a social life. It connects to Looking for Langston and the Harlem Renaissance. He has a wardrobe for the day and then a nighttime wardrobe, which is a lot more sensual. It was about these restrictions in tailoring based around something very minimal and utilitarian, but which was also able to communicate a sort of softness. That was also the collection where I integrated some imagery from Carl Van Vechten’s series of homoerotic photography, as well as an image from Chris Ofili’s Blue Riders. It was about exploiting the idea of a blue mood through art and literature, and it became a meeting point of these different things. For the Autumn/Winter 2018 collection, Des Hommes et des Dieux, I also worked with archival materials, that time with Jacob Lawrence’s imagery in clothing. I’m interested in how you can integrate images into clothing and talk about histories.

Before we talk about the Serpentine show and the latest collection, which go together, could you maybe tell us about your first Serpentine collaboration? We met in 2015.

I remember having a meeting in this office and I brought you the zine Everythings [sic] for Real.

And then we invited you to take part in the 2015 Transformation Marathon. That led to something that wasn’t fashion or exhibition, but performances you also called Everythings for Real. For that you collaborated with the extraordinary Moussa Dembele and Moussa Dembele, who are like twins but aren’t really, from Burkina Faso. Can you tell us a bit about this first event at the Serpentine?

I was interested in the Transformation Marathon and I remember meeting Moussa in London. He was a street performer and seeing him made me think about transformation and how we could present that in another space. So we got talking and I was interested in him performing and then I also asked him if he knew other people. Online I had found another balafon player and Moussa said that he knew him. So we managed to get him here as well. I created costumes for that performance and I instructed them how to play. I don’t come from a musical background, but I was thinking about another way of performing. That performance was very intimate.

Is this Serpentine show, A Time for New Dreams, the first time that you have actually curated an exhibition?

Yes, this is new for me. Lots of strands have been part of my artistic practice for a long time – the research, the histories and bringing together collaborators in dialogue – so there is continuity, but I’ve never had the opportunity to be in a space for a longer period of time. To be able to present something over the course of months as opposed to one day is really interesting, being able to stretch time and yet be present in a space for a period.

Tell me a little about the show’s title, which is taken from Ben Okri. How did you come to the title and the idea of the altar, the ritual, the procession?

It all comes from research. One of my starting points was Robert Farris Thompson’s book Face of the Gods, which explores altars and connects rites and forms of spirituality, and how that is manifested across the black Atlantic. I was looking at the strength of that, and how African-American artists interpret ideas of spirituality and magic. It connects through a wider lineage of aesthetic practices, so it is about tracing those threads. From that very specific research point, it expanded, opening up dialogues with other artists who consider how we reflect on where we are and what came before.

‘Even though it seems like a difficult moment, it is a time to really connect, to talk to a community. It is time to embrace and encourage each other.’

Besides Ben Okri, another inspiration was Ishmael Reed, a great writer. You named your Autumn/Winter 2019 collection, which will be presented in the exhibition, after Mumbo Jumbo, his

1972 experimental novel about race in the United States. It is set in 1920s New York, and encompasses voodoo, jazz music, and white supremacy, while politically subverting these artefacts

with magical realism. What was Reed’s influence on the show and how will the exhibition lead into your new show?

I am really interested in the way his writing has a magic-realist potential; it is complicated, layered and evolving. That kind of shuffling and ‘rhythmizing’, I also see in my roots in terms of rhythmizing textiles. Ishmael’s own wardrobe and the clothes worn by black intellectuals come into my collection, and I think the space creates an environment in which characters that I have imagined live. It connects to traditions of storytelling, oracles and oral cultures and passing on through generations. Writers like Ben Okri have really important roles to play in connecting people with this rich history, magical history, and I think that in the time we are living in, it is important to acknowledge these guides.

The Mumbo Jumbo collection brings together many of your research threads that are also part of the exhibition. How do these characters fit in and create the world of your collection, this polyphony?

There are two sets of characters, one is the black genius who is underrepresented, and the other is neo-hoo-doo idea of the artist as shaman.

There is also the idea of how you use fashion as a medium to tell stories. You invent these characters, like a play. How does this storytelling relate to performance?

We often talk about the subtlety of gesture, very simple things that one can do to disrupt a flow of what is expected. When I think about characters, it is about them owning their space and the world they inhabit, and for them not to be conscious of an audience.

All your collections address black masculinity, and using your research, you draw upon certain histories or narratives. Tell us a little bit more about this big theme and how your research into it

has evolved and where it is going next.

At the core of everything I do is research – that is the core of my collections, and fashion is one outlet through which I explore those ideas. Black masculinity is a subject I have continued to study. It is not a fleeting interest; it is something integrated into my work. I am starting to think more about the Caribbean, a place where I need to spend more time, and with this collection, I have also been researching more about Haitian voodoo practices. I’m excited about going to Guadeloupe with the Durimel brothers to shoot the pictures that will accompany this interview. I feel an urgency to be in that space and at the same time I want to spend some time in Trinidad as well. It seems like I am being gravitationally pulled to Caribbean islands, so that is exciting for the next step.

What are you looking to do in Guadeloupe?

The shoot will be very much a reaction to the island. I am grateful that the twins partly grew up there and have so many memories of Guadeloupe. They have told me so much about it. I think it is going to be about memory and places on the island and communicating connections with the water and spirituality in that space. They talked to me about the different traditions, the ceremonies, processions and masquerades that are very specific to Guadeloupe, which I am really interested in researching more.

How do you feel about the future? Are you optimistic?

A special energy came with me into the new year, and among my peers as well; I saw there was this optimism. The environment around us is very harsh, but I think that there is space for hope in this

time, and I think that the younger generation really needs to be part of maintaining that and connecting people. I think it is really important to be rooted in this time and to acknowledge what has come before, but also what is happening in this moment. Even though it seems a difficult moment, it is a time to really connect, to talk to a community. It is time to embrace and encourage each other.

Production: CLM US and Francis McKenzie.

Casting: Sydney Bowen.

Models: Romaine Dixon and Christine Willis @ Saint Models, Dhayjanire Louisanneau.

Special thanks to Rana Toofanian.