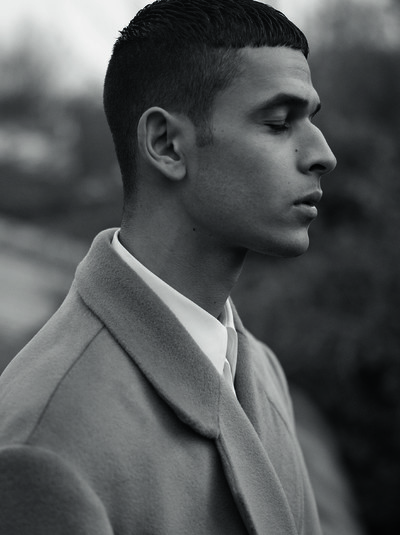

The story – and back story – of an encounter between tailored clothing, long-lost elegance, and young French men of North African descent.

Photographs by Karim Sadli

Styling by Joe McKenna

Text by Farid Chenoune

The story – and back story – of an encounter between tailored clothing, long-lost elegance, and young French men of North African descent.

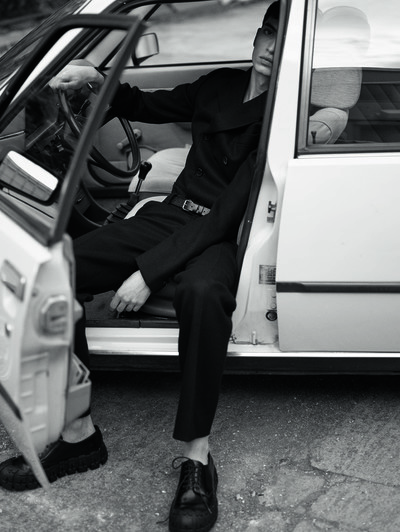

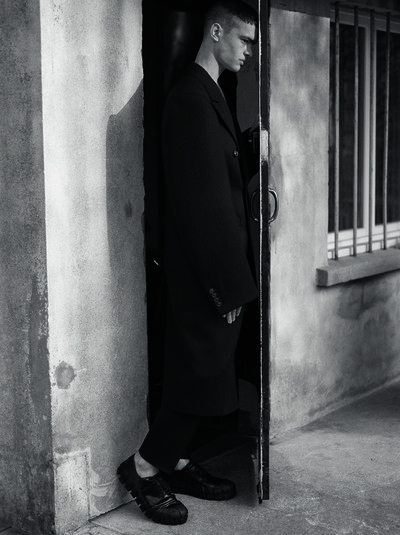

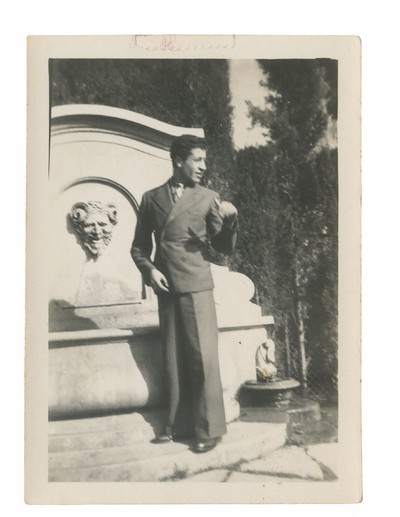

Certain fashion shoots come loaded with an unexpected and sometimes clandestine back story, a sort of prehistory. Karim Sadli’s photographs, presented over the preceding pages, for example, discreetly tell the story of an encounter, between intricately tailored clothing and young French men of North African descent from the Parisian region. Crudely put, teenagers brought up on streetwear. But that back story itself is based upon another story, one that came to Sadli when he watched a documentary about the demonstration of around 30,000 Algerians in central Paris in 1961. It took place at the height of the anti-colonial war in their homeland and by the time the march was over, somewhere between 30 and 100 Algerians – to this day no one knows exactly how many – had been killed by the French authorities, and many of their bodies dumped into the Seine. ‘My grandfather was there,’ says Sadli. In photographs of the events, many of those Algerians, who often lived in shanty towns just outside Paris, are seen dressed up in their Sunday best, however worn and tattered it might have been. These smart clothes and suits become visual markers of a dignity that they had always been denied by the French state. ‘I found their story so touching,’ says Sadli. ‘That’s where the idea for the shoot came from.’

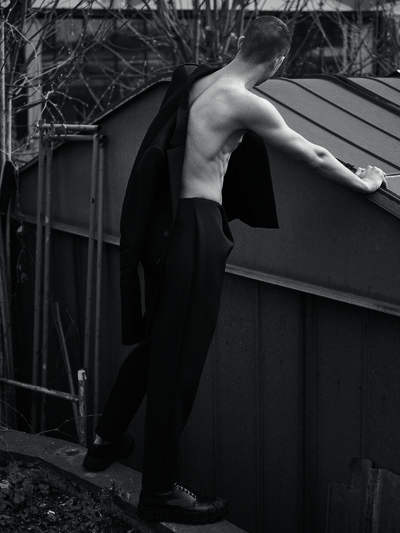

Sadli sees his project as almost utopian, a ‘fantasy’. The teenagers of 2019 he cast considered it outlandish. The Algerian War? Barely heard of it. Suits, jackets, neatly pressed trousers, and tailored coats? From another world, light years from their hoodies. Nevertheless, the process became a revelation and, to put it grandly, a moment of historical transmission and initiation. For transmission, these young French men ‘from an immigrant background’, as the French expression ‘issus de l’immigration’ describes them, took the past they knew little about extremely seriously. ‘They were amazed to discover that French colonialization in Algeria lasted 130 years,’ says Sadli. ‘I don’t know if they took this story to heart, but sharing it with them helped them make sense of what I was asking – to be photographed in a suit – something that had initially appeared completely incomprehensible to them.’ The initiation took place through wearing the clothes.

Alongside Sadli, the other guide was Joe McKenna, the series’ stylist. The clothes he’d selected were structured, and cut in dense, mainly rigid fabrics. ‘Everything is highly restrained,’ says Sadli. ‘Joe is extremely meticulous in his way of putting the clothing in place, in arranging a pleat. Nothing is left to chance.’ The shoot was perhaps the first time that the young men, more accustomed to the loose nonchalance of sweatshirts and sweatpants, have felt so ‘relied upon’ by their clothes, which, in this instance, required them to move, to hold themselves, and to stand in entirely new ways. ‘Some arrived for the shoot literally trembling with nerves,’ says Sadli. ‘But as things progressed, I saw them transformed and really getting into it, as if they were gradually understanding what Joe and I were looking for. I felt it all clicked into place when they started gently teasing one another, cracking each other up: “Ouais! La classe!” By the end, they’d completely made the clothes their own, and clearly enjoyed the experience.’

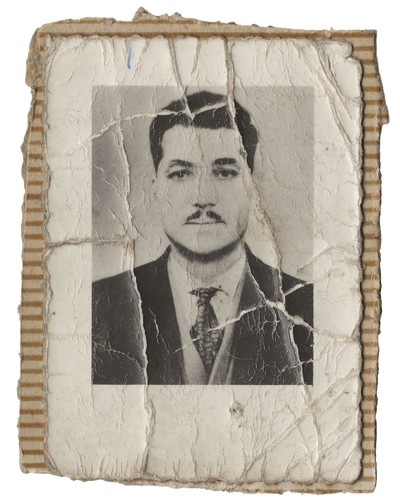

As I listened to Karim Sadli, and looked at his photographs, and then wrote this short text, I thought about my father, Algerian, like Karim’s grandfather. He too was looking for dignity and respect, and throughout his life he expressed that desire through sartorial elegance. He was proud of it and, without really understanding it at the time, I was proud of his pride. He had four or five complets, as suits were referred to in French back then, and they were his working capital. He would renew them at his tailor, Jacques Deligny at 38 Rue du Mont-Thabor in Paris, whenever he could afford to. I have kept some of his complets from the 1960s and 1970s, including one that is cut straight and has a single button. A spring suit, in light pigeon grey, shiny and slightly electric, it continues to emit the same lustre, the same aura it did when my father wore it. I remember the care he took getting dressed each morning, carefully constructing an appearance to show the world. The ceremony would culminate in the final adjustments, when he would check that everything was in place. The shape of the shoulders and the position of the shirt and jacket collars were particularly decisive. So when Karim described Joe McKenna’s gestures to me, I saw my father: meticulous, as precise as an acupuncturist. Whether the young models themselves felt the shadow of this long-lost elegance pass over them will probably never be known, but ultimately, it’s these unspoken layers of back story that make the series all the more intriguing.

Models: Khalil, Mehdi, Alexandre J., Keenan, Malek, and Ali.

Hair: Damien Boissinot @ Art + Commerce.

Make-up artist: Christelle Cocquet @ Calliste Agency.

Manicure: Julie Villanovas @ Artlist. Tailor: Sebastian Pleus @ Atelier On Set.

Set designer: Alexander Bock @ Streeters.

Photography assistants: Antoni Ciufo, Thomas Vincent, Chiara Vittorini.

Digital operator: Édouard Malfettes @ Imag’in.

Styling assistants: Gerry O’Kane, Ricky van Gils, Edward Bowleg.

Hair assistant: Kyoko Kishita.

Casting director: Martin Franck.

Production: Brachfeld Paris.