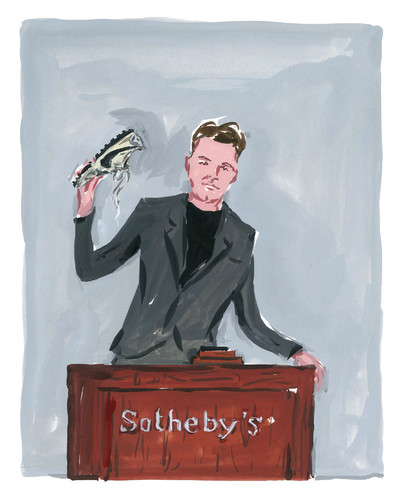

Why today’s sneakerheads shop at Sotheby’s.

By Noah Wunsch

Illustration by Jean-Philippe Delhomme

Why today’s sneakerheads shop at Sotheby’s.

My first online-only auction in my new role running global e-commerce for Sotheby’s was a single lot made up of every model of Supreme skateboard deck ever manufactured. The sale was to happen during our January 2019 Americana Week, during which decorative arts, manuscripts and memorabilia are sold in several auctions, and are top of our clients’ minds. There, on the seventh floor of our New York City headquarters, surrounded by letters from Alexander Hamilton and George Washington, were 248 skateboards featurng artwork by Jeff Koons, George Condo, Richard Prince, and many other blue-chip artists whose works have sold for millions in Sotheby’s contemporary-art auctions. The night before the auction’s close, however, we had received exactly zero bids on a sale that felt ‘sink or swim’ for me. I stayed afloat: the bids came in during the last five minutes of the auction’s close, as beads of sweat ran down my forehead. New category collectors are digitally native, and recognize the value in waiting for that countdown clock to turn red. In the end, the boards sold for $800,000 – to a 17-year-old in Vancouver.

It’s a fascinating time in the art and luxury market. Traditional luxury brands have recognized the value in production transparency: providing customers with a specific number of produced pieces (known as an “edition run”) drives interest. It’s similar to prints in the art world: a David Hockney print from an edition run of 50 is likely to be more valuable than one from an edition run of 250 (I say “likely” because there are various heuristics that go into pricing works, but scarcity is certainly important). Similarly, a Louis Vuitton skateboard, manufactured by Supreme in 2000, is more valuable than other boards in the collection, because the production run was pulled after Louis Vuitton sent Supreme a cease-and-desist letter for the unauthorized use of its logo.

Even before the success of the Supreme sale, I had wanted to do a sneaker auction. The category’s growth over the past decade has been astronomical. It’s an industry worth over $60 billion, and has created a secondary market worth anything from $300 million to $1 billion. Similar to categories like art, jewellery, watches, and others offered in Sotheby’s auctions, there are clear criteria that serious sneaker collectors use to decide value. Are the shoes in pristine shape or game worn? Who designed them? Are they from a specific production run? Are they associated with a historic moment? The list goes on, as does the process for authentication (which includes stitching, colourway, and even smell). Sneakers are universal – nearly everyone has a pair – and just like the art you hang on your walls, the shoes you put on your feet convey a message.

To build our sneaker auction, Sotheby’s found an amazing partner in Stadium Goods, the premier sneaker and streetwear marketplace, which helped put together our Ultimate Sneaker Collection. It comprised 100 of the rarest sneakers, including the 1972 Nike Moon Shoes, created by Bill Bowerman, co-founder of Nike and Oregon State’s famed track coach, of which only about a dozen pairs were made. To the best of our knowledge, the pair offered in the Ultimate Sneaker Collection was the only unworn pair in existence. Think about that – billions, likely trillions, of shoes have been produced over the last six or seven decades, yet one of the original prototypes, which would set off a new sphere of design, fashion, and sport, has been left unworn for 47 years.

The pair had a low estimate of $110,000 and a high estimate of $170,000. Was I surprised that they sold? No. Was I surprised that they ended up breaking the record for most expensive pair of sneakers ever sold at auction, going for $437,500? Honestly, a little. But the significance of that pair as a cultural totem is real.

People speculated that we would see a similar result to the Supreme sale – surely only young people would be interested in the category. So did a 17-year-old in Vancouver buy them? Was the collector a hypebeast? In the end, one buyer purchased the entire collection: Miles Nadal, a middle-aged businessman and rare car collector, who saw a similar beauty in the production design of the sneakers.

Luxury collectibles are new market categories, just as stamps, coins and watches once were. Their utilitarian nature drives scarcity, which increases interest and value. It’s not the last time the record will be broken, and it definitely won’t be the last sneaker auction at Sotheby’s.