There’s nothing nostalgic about fashion’s enduring love of vintage Stone Island.

By Angelo Flaccavento

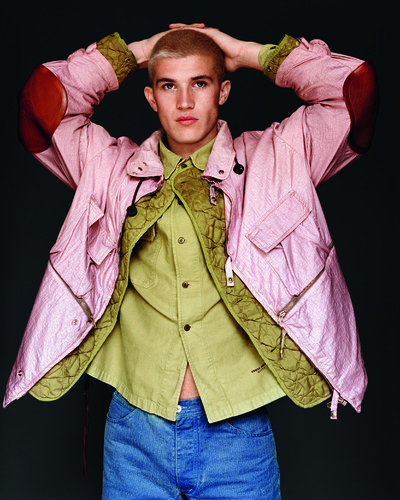

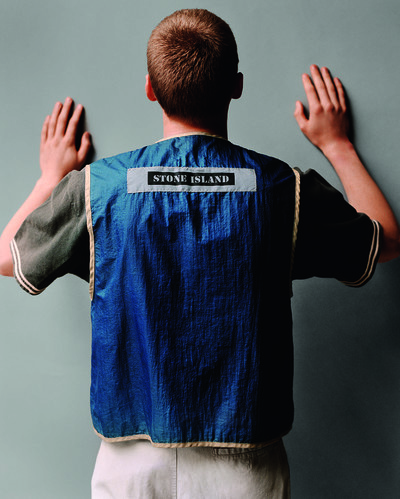

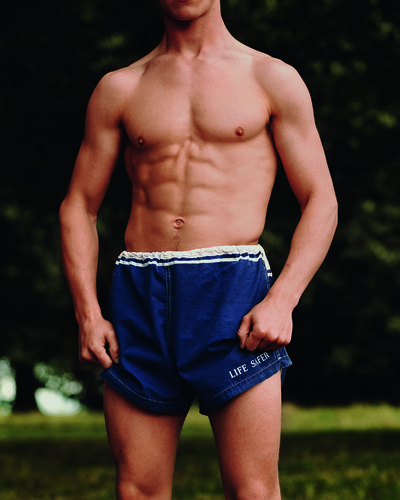

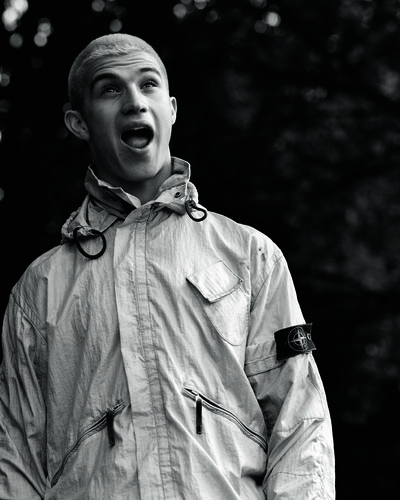

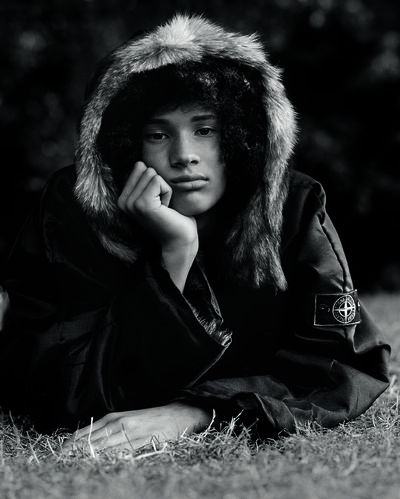

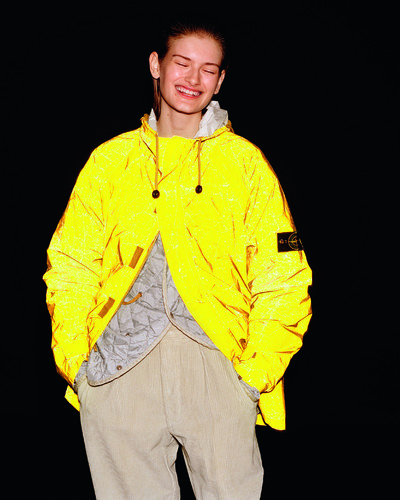

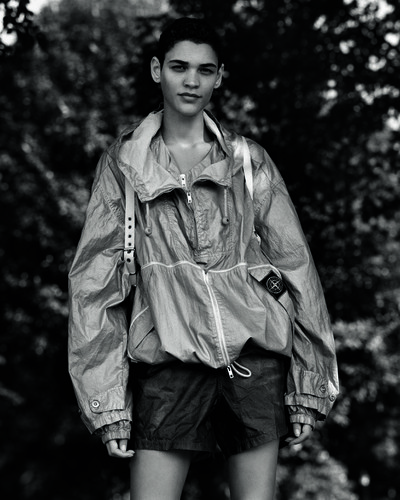

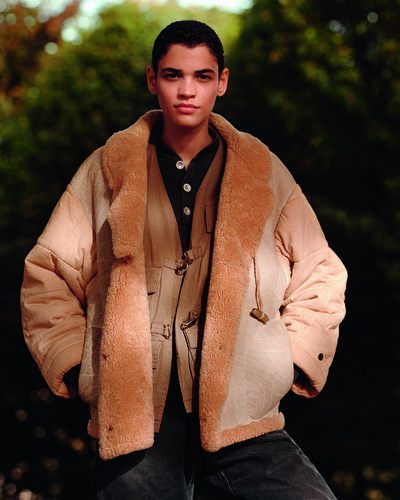

Photographs by Alasdair McLellan

Styling by Max Pearmain

There’s nothing nostalgic about fashion’s enduring love of vintage Stone Island.

Every original’s real achievement is timelessness. To survive the test of time and to earn the right to go beyond the minutiae of the here and now require focus, a radical belief in one’s own vision strong enough to resist passing trends and fads, and avoid selling out. Only history can tell what will survive, of course, and even history sometimes succumbs to the ephemeral, yet originals are both rare and easy to spot. Massimo Osti is one, a designer who earned his right to join the pantheon alongside Issey Miyake, Rei Kawakubo and Giorgio Armani. ‘Osti had an eclectic eye, finding inspiration in military uniforms, workwear and sportswear, all of which are staple design influences nowadays, but were far less so then,’ says veteran stylist Simon Foxton, who has been working with Stone Island for over a decade (but never with Osti himself). ‘His genius was then to take those ideas and remould them into something totally new and modern in look and feel. This was the DNA of the company he created and his legacy still holds true today.’

Massimo Osti devoted his entire output to men’s sportswear, and he courted neither the flashy and wealthy, nor the creative and crazy, but ordinary customers living in cities. ‘I think football fans and fanatics took up Stone Island so enthusiastically for a number of reasons,’ says Foxton. ‘It feels and looks expensive – which it is – so it is a status symbol, but not in a flashy here-today-gone-tomorrow way. It is more like a well-designed car or motorcycle. It assiduously avoids being seen as a “fashion” label.’ Osti did not even consider himself a fashion designer – and coming from a graphic design and communications background, he was not. He did not do high fashion but the clothing he invented at his labels Stone Island and CP Company – bold and futuristic at the former, soft and welcoming at the latter – have lost none of their power in the three or four decades since their launch. ‘I would definitely put him in the same league as Helmut Lang,’ says stylist Max Pearmain, who is a long-time fan of Osti’s work. ‘He was a game changer.’

Massimo Osti died, aged just 60, in 2005, a time when his star had probably begun to wane. Back in the early 1980s, with business booming, Osti had sold a majority stake in Stone Island and CP to Carlo Rivetti, the owner of Sportswear Company. By the mid-1990s, he was finding being both a designer and an entrepreneur gruelling, so he walked away from it all. He launched a number of ventures, some successful (Left Hand), some less so (Massimo Osti Production), but all short-lived and marked by his reuse of previously used shapes and fabrics. Throughout his professional life, despite introducing groundbreaking innovations in techniques such as garment dyeing or wool brushing, despite using daring heat-sensitive and highly reflective fabrics, despite turning the humble down jacket into a urban staple when most people were still only using it for skiing, and despite almost immediately gaining a cult following – even if the object of the cult was the product, not its designer – Massimo Osti was never considered as one of the Italian megastars, such as Valentino, Gianni Versace or Gianfranco Ferré. It was perhaps because he was always pigeonholed by the press. Osti did not really care, however; he liked playing his own game too much, took too much pleasure in skewering the auteur rhetoric that was integral to the meteoric rise of the ‘Made in Italy’ movement. He was always too busy working on some fabric treatment,

collaging bits and pieces into wholly new shapes, to really care about flaunting his own lifestyle for promotional reasons or pontificating about fashion with a capital F and hogging the limelight. His passions were adventurous and intensely physical. He loved sailing, for instance – it was not by chance that he chose a compass rose as the Stone Island logo – but his passions were also private. He wasn’t interested in creating status symbols that helped other people do the same. There was a distinctively Bolognese laissez-faire to such a benevolent disdain for the demands of fame. Particularly as it was the 1980s, when fame was a social must, and swimming against the current required nerves and guts.

Massimo Osti’s oeuvre remains so relevant today that it almost needs to be written about in the present tense to be properly dissected. (The images that accompany this story, styled by Pearmain and photographed by Alasdair McLellan, are proof of such unadulterated nowness.) His work intertwines inventively functional shapes, painterly colours, and engaging textures because Osti approached garment-making as a three-dimensional endeavour: it was about form not just image. Working intensively with fabric treatments like dyes and stonewashes, he mastered the art of giving clothes an intensely worn, but not destroyed patina. Even at their brightest, Stone Island or CP Company garments – outerwear, mostly – never looked brand new, stiff, glaring or garish; not even the reflective pieces came across as cold and industrial. Instead, they all proudly wore a touch of history on their surfaces, like they already had adventures to tell. This pre-life embedded in the fabric might partly explain their timelessness. Take the wonderful Tela Stella, a stonewashed canvas based upon truck tarpaulins and impregnated with resins and aged with enzyme washes, which was the material of choice for the first three Stone Island collections. Pearmain calls it ‘so raw and straightforward that it has an Arte Povera glow’; it proved so popular that supplies were actually rationed.

Massimo Osti devoted his entire output to men’s sportswear, courting neither the flashy and wealthy, nor the creative and crazy, but ordinary customers.

Timelessness is also a matter of shapes, and signature Massimo Osti garments do often look like rethought archetypes. He reinvented the once-codified iconography of parkas, field jackets, riding coats and blousons, which he constantly spliced, dissected, reassembled – but never distorted. As a result, an Osti design feels both familiar and alien in equal measure, with his clever use of copywriting adding the final coating of progressive pragmatism. (Both fabric and styles were given simple, but memorable Italian names that hinted at Osti’s background in communications.) While there was a free-wheeling inventiveness to his work, it never came at the detriment of function, which Massimo Osti considered essential; every little detail had a reason, from a dart placed mysteriously on an elbow or a ridiculous number of pockets. His garments, as a result, embodied a reassuring brand of straightforwardness – they felt like design objects, not silly fashion pieces.

Such originality was the result of Osti’s unique way of working. An avid collector of vintage militaria, he built an extensive archive that functioned as the primary source material for everything he did. When working on a piece, he rummaged throughout his archive, pillaging anything that took his fancy – a sleeve here, a pocket there – and collaged it back together into something new. He photocopied every detail of the originals, before stapling and gluing together a life-sized model that allowed him to keep everything under control.Fabric research was carried out in parallel, the Osti signature being an exacting seamless merging of shape and texture.

The results were always smashing. In 1983, a Zoltan cape-tent originally made for the German Army was reworked into Zeltbahn, a Stone Island gem, all askew buttoning and flowing volume, with bright Tela Stella adding a bold twist; in 1988, Japanese gas masks inspired the goggle lenses incorporated into the hood of the CP Company Millemiglia jacket, an immediate hit.

To show you how much Massimo Osti could strike a chord, let us return to 1980s Sicily. I was in high school when that Millemiglia jacket came out – and it was a sensation. The goggles on the hood felt almost like Blade Runner; it was all performance-art Mutoid Waste Company, yet the jacket’s tobacco-brown fabric’s lived-in patina made it look easy to wear. The only minus was the hefty price tag, of course. Indeed, the local boutique in my hometown of Ragusa carried just the one piece. Luckily, it was my size. I begged my mother to buy it for me. Knowing full well of my sudden about-turns with items of clothing, particularly those I most pestered her about, she told me to wait. Trying to act mature, I accepted. When I rushed back to the shop the following Saturday, though, I had a shock: the jacket had been sold. I was in pieces, and I felt even worse when, from the shop window, I saw the man who had bought it, a young architect, passing on the street. I was so disappointed that I refused to buy a Millemiglia the following season, when it became a carry-over item.

My love affair with Osti, however, goes far deeper than that single episode. I used to actively look for his designs and my memories are full both of pieces I did purchase – the field jackets, the incredibly supple garment-dyed shirts, and the ruby-red Shetland wool CP Company cardigan that I bought in 1992 as a freshman at university and still wear today – as well as pieces I never managed to get my hands on. Like the celebrated Stone Island Ice Jacket, which changed colour according to the wearer’s body temperature. A remarkable item, I wanted one so very badly, and in hindsight, I should have bought what became an instant collector’s item. Back in the day, though, the idea of a parka that would react to my body heat – changing colour with my emotional reactions – made me freak out. Reader, I did not buy it.

It is more like a well-designed car or motorcycle. Osti didn’t even consider himself a fashion designer. And coming from graphic design, he was not.

The images in this story, just like my vivid memories, are filled with Stone Island archive pieces that do not smell or spell past, but talk of the now. (Indeed, some are still being worn.) They demand no nostalgia from me – first and foremost because Massimo Osti hated that sentiment. Who could blame him? Nostalgia, if interpreted merely as regret for a better past, is a paralysing feeling: an invitation to linger and whisper, to look back in angst and despair, safe in the knowledge that today is worse than yesterday. Massimo Osti was having none of that; he was always looking ahead, taking the best from the past, but making it defiantly of the now. That very Italian way of looking forward not only feels urgent and useful today, but also like a way for fashion to escape the quicksand of dry, soulless marketing, the fundamental dishonesty of relentless product-making that is the devilish cover up for a widespread lack of ideas in this saddening historic moment.

Massimo Osti was a man of ideas, full of concepts that mattered, not layers of varnish over nothing – and he worked hard, if playfully, to make them happen. The tags on his items always stated it clearly: ‘Ideas from Massimo Osti.’ There’s a lesson there, in that enthusiasm for ideas. There’s an honesty, too, a value that should be never be taken for granted or underestimated. Massimo Osti was not a marketeer; he was a builder. His aim was not personal stardom or influence, but something as simple as making his clients’ lives easier. By working like an industrial designer and by putting the consumer first, Osti imbued his work with a truthfulness that today has been completely erased by the idea that astute storytelling can help selling nothingness as genius. This stress on the product came from his non-professional background. For writer Alberto Abruzzese, Osti was a ‘producer’ who followed each product from its design inception to production to the advertising campaigns, which often featured clothing industrially photographed as still lifes. Osti managed the balance of material and immaterial, of product-making and communication with acumen, smartness and a coherence that came from his Italian outlook.

In our ever-connected globalized world, national identities might appear irrelevant to fashion, but a local spirit is an essential ally in the war on the generic. To me, Massimo Osti is the quintessential Italian creative: one driven by a no-holds-barred hunger, a brutally pragmatic hands-on approach and a positive, nothing-is-impossible outlook on things. As an Italian, I see Osti’s take on creativity and entrepreneurship as fitting perfectly into the enthusiastically industrious Emilia region of central Italy, and in particular in the city of Bologna, where he was born and bred.

His studio was on the central Via Zanardi, the same street as the main faculties of the local university, whose history harks back to the Middle Ages. For non-Italians it can be hard to understand how Italian identity is a composite, excitedly fragmented affair, not monolithic. For centuries, after the fall of the Roman Empire, we have been a land of little commons and little feuds, and we have always nurtured our genius loci with immense pride, trying to be as different as possible from our neighbours just a few kilometres away. Massimo Osti was an original, but originality does not happen in a void; Bologna is integral to his story – it could have never happened in the same way anywhere else.

Bologna in the 1970s and early 1980s was a particular, anomalous, free creative zone: a place bursting with incendiary energy in every field, from music to theatre to art. Ideologically speaking, it was just as peculiar, sitting at the crossroad of leftist rebellion, irony, absurdism, and an unprecedented stress on the multidisciplinary. It comes as no surprise that the first academic ‘interfaculty’ dedicated to arts, music and performing arts – named DAMS and with Umberto Eco on the staff – opened in Bologna, attracting renegades from all over the country. It all coalesced in the Movement of 1977, a politically countercultural moment that was dreamily ironic rather than gritty, with great music, great writers and great fanzines. While not active role in the rebellion, Osti was part of the milieu, breathing in the atmosphere, and anonymously supporting Frigidaire, an incendiary publication that mixed comic strips, literature, art and porn in equal doses, and remains influential today. Osti was just as free in his professional approach and his openness. He started in fashion by bringing his graphic-design sensibility to a series of screen-printed T-shirts that were different from anything else at the time. That spark, that ability to talk to the public and create a reaction, stayed with him all along his career.

‘A cult inspires the notion that the thing you worship is singular,’ says the stylist Max Pearmain, ‘and to my eye Osti is one of a kind.’

Which brings us to the final and central topic: the cult. Massimo Osti let his work speak for itself, an approach that attracted followers immediately. For Stone Island, among the first were the Paninari, perhaps the only indigenous Italian subculture. Paninari had a wide demographic, going from the square to the quasi-edgy, and while the average Paninaro was happy with a Moncler puffer, the movement’s cognoscenti were quickly worshipping at the altar of the experimental, expensive and elusive Stone Island. (The more painterly CP Company and CP Collection became the uniforms of choice for the artistic and creative communities.) Stone Island evolved into an enduring cult, one still alive today in particular in Britain, thanks to its popularity with football fans. ‘The cult was definitely brought back to Britain by supporters who came in contact with the Paninari in Italy,’ says McLellan. ‘Owning and flaunting Stone Island made you royalty back in the day.’ New Stone Island continues to be produced and bought, but true obsessives collect vintage Osti designs, such as the items featured in this story.

Buying an Osti piece is probably a good investment. Stone Island has never been silly or predictably fashionable, and the boldness it oozes is palpable. That makes followers fervent and eager for more. On top of which, it is extremely functional. ‘A cult inspires the notion that the thing you worship is singular,’ says Max Pearmain, ‘and to my eye Osti is one of a kind.’ Such cultish Massimo Osti dedication somehow closes the circle in a proactive way. The enduring relevance of

this master of form and function lies in his unique ability to communicate, not through advertising or press releases, but rather through the clothes themselves. Straightforwardness equalled inventiveness for him. A purveyor of visionary pragmatism, Massimo Osti changed fashion at its core, forever. In fact, you might well be wearing something he invented a long time ago, even though he didn’t actually design it – and that is a genuine achievement.