Young Turks is the record label that could teach luxury fashion groups a thing or two.

Young Turks is the record label that could teach luxury fashion groups a thing or two.

Young Turks, the term used to describe an insurgent group seeking radical change, is also the name of one of pop’s most forward-thinking record labels. Launched in London in 2006, it was founded on the idea that the healthiest trajectory for a musician sits outside the standard (and, depending who you ask, stifling) model of studio, album, promo, tour, repeat. The label or collective – whatever you want to call it – is the brainchild of Caius Pawson, the publicity-shy impresario whose unique take on music management has fostered the careers of cult music artists including The xx, FKA twigs, Sampha and Kamasi Washington.

In 2019, music has never been more visual; fashion has never been more experiential. So, for a forensic look at the state of relations between fashion and music now, Pawson and his Young Turks seemed an ideal place to start. He’s spent years encouraging his eclectic roster of artists to flex their muscles across the fields of film, art, fashion, design, choreography, and curation; although he’s keen to add that the odd album or EP is nice, too. Think of the label as a pioneering (and infinitely nimbler) music-world counterpart to fashion’s luxury conglomerates, where a variety of points of view under the same umbrella allows for a very special kind of cross-pollination.

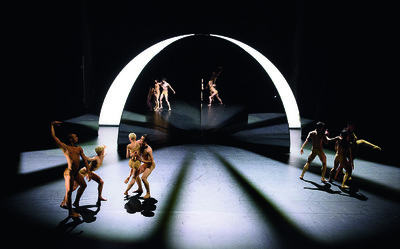

In the following pages, Caius Pawson shares with System the history of Young Turks, before unveiling The xx’s latest ‘extra-curricular’ project: a 10-year anniversary merch collection, designed in collaboration with Raf Simons; presented for these pages by Simons’ own long-time image-making allies Willy Vanderperre and Olivier Rizzo; and the subject of a think-piece by legendary art director Peter Saville entitled ‘What is merch?’ Followed by a three-way conversation between electronic music artist Koreless, L-E-V choreographer Sharon Eyal, and Young Turks’ in-house curator (yes, they have a curator on the payroll) Claude Adjil, exploring the strange and beautiful alchemy of cross-cultural collaboration, captured in a portfolio by Harley Weir. For those in fashion just waking up to the groundbreaking possibilities of kicking down the doors between disciplines, Young Turks is proof that it’s no mere trend – it’s the indisputable future.

Rana Toofanian

Caius Pawson at Young Turks’ East London headquarters.

Portrait by Chris Rhodes.

‘I am interested in what people in fashion

can teach musicians and vice versa.

That’s more exciting to me than just an

artist wearing a designer’s clothes.’

A conversation with Caius Pawson

by Jorinde Croese

Let’s talk a bit about your backstory. What do your parents do?

Caius Pawson: My mum works with visual artists, and my father is an architect. I grew up around a lot of that, but not involved in it. I didn’t take to design, architecture or visual arts particularly fluently. The first thing that really struck me was music, and then I made my own way into that, but that wasn’t until later. When I look back on it, I realize how much my parents’ approach to what they do influenced my approach to what I do.

What was their approach?

My mother is very detail-oriented. She’s obsessed with artists and protecting their integrity, as well as that of the work. Especially the context in which the art is received by the audience – from the placing of the work, and how the artist was being shown, either curatorially or where an art piece was, what it was next to and what the larger context was. The artist was always number one to her. She had a healthy disregard for the mechanisms of the industry around it. She was always pointing out the chasm between what the industry was trying to do and what was the artist’s core thing. She was always very intent on ensuring that the artist’s working practice was focused on making the best work and not just having to churn stuff out to feed endless art fairs. At the same time when the work was shown, it was shown with integrity. She was also my father’s first client three times over. So his aesthetic grew with hers. She was very influential on that. She has always lived in his works as long as I have been alive, so I grew up in and around that work, and seeing how they both reacted to it. And then, you know, my dad is someone who will endlessly move one object around the table until the light hits it in the right way, and he will take 3,000 photos of the corner of a room or an edge or the way something touches. His obsession is the detail of his work; my mum’s is other people’s work being protected.

He was the artist and your mother…

He would never call himself an artist, but yes, exactly. She had a huge respect for the artists and I think I learned my respect for artists from her. I never really met the artists, though. My childhood was a childhood; I wasn’t learning from artists. I was learning from my dad, but he wasn’t pushing anything on me. I wasn’t going to see Mies van der Rohe houses or Le Corbusier buildings; I was swimming and playing football. I went to a lot of classical concerts with my mother because my uncle was artistic director of the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, and my mother had developed a real interest in classical music. I saw and heard a lot of that when I was younger, but it was rarely pushed on me. I think what they were doing was something quite radical, and to do something radical you have to break from tradition. So then, this idea that you push tradition onto your son just wasn’t there. What happened for me was that I first heard pieces of music that changed me physiologically, where I could feel a chemical shift in me when I heard that music, like it triggered something hormonal. Before I did my first ecstasy and felt that serotonin rush, I heard bits of music as a pre-teen that did that to me. That probably happened five or six times when I heard a piece of music and walls broke down. I went to a school where a lot of your time was free time. I investigated making music, but it never came naturally to me. It took me 10 years to learn the guitar, and I still couldn’t really play it. I remember the first time I met a serious musician at school, a guy called John Jackson, he would play and my spine would light up, neurons firing right up and down it. That was when I probably first thought I needed to be around artists. I started to organize concerts at school; there was a concert called JFP, which stood for Jazz, Folk and Poetry, but we changed it to Junk, Funk and Punk, and that allowed me to become a concert promoter. As soon as I left school, I started putting on parties, threw raves, club nights, gigs; it was like a natural continuation. There I discovered the wonders of nightlife. There were the huge highs of having hot shows that sold out, and making loads of money when you’re an 18-year-old. It was very easy to have an idea, an ambition, and then manifest it in a one-month period. But then when it went wrong you lost all your money and it was a complete social humiliation on a scale I have never known since. Your idea either rides or dies. I loved the immediacy of the events, though, and the fact it brought all these people to me: artists, managers, labels, people on the scene. People just interested in culture and you were the epicentre of it for one night. Then once it was over, they were gone and you’d have no connections again. Then there was all that came with it: the gangs that own nightclubs, the dodgy council people we had to pay off, money getting stolen. We were doing club nights and raves and then the high of the club nights wore off. Clubs got a bit safe and I very much missed the free rave era. This was about 2005 by that point. We did a rave in an old Transport for London office block, and by this point we were using Myspace, sending out bulletins and telling people to come. But the police were trolling Myspace, so that was a really dim promotion. We weren’t even really booking acts; great DJs were just rocking up wanting to play. We put on four floors of raves, one big bar, three rave rooms. We brought the sound system in the night before and we slept in the venue. It was grim. And then the next day the rave started, by 11pm it was rammed, and by midnight the riot police arrived. We had ice being delivered, but the police shut the road, so the ice was just being dumped by the side of the road. Kids were chucking ice at the police, people were peeing off the building onto the police. I thought my life was over, but that was when I met Richard Russell who owned XL, because he had come to DJ. He said to me: ‘You should come and do this at my record label.’ So I went to work for XL, which is a sort of classic independent record label that he founded in 1989. It was the epicentre of the rave and hardcore scene and went on to sign acts like SL2 and the Prodigy that topped the charts. And then XL had two or three major rebirths moving from a rave label to the best of each really incredible dance music scene to garage, and now it is an artist’s-artist label with the likes of Radiohead and White Stripes, Dizzee Rascal and MIA, hundreds of acts. It was always about finding an artist who was ready to have something unique amplified. Artists who were completely themselves and didn’t fit into any mould or genre, or maybe came from a scene but were genuinely themselves. Then XL helped amplify them in the most realistic way possible. It was a really beautiful place to go because it was all about backing the artists and their vision. When the industry tried to mess with that or tried to put limits on it, XL would back the artist. The Prodigy never did any TV, and at the time if you were an act of the Prodigy’s size you had to do TV. XL was very good at having faith in the artist and so they got to work with all these incredible artists who all had their own unique identity. I had grown up loving labels like Motown and Warp where it was a very distinct sound in a very distinct time and place, and the way it was presented was beautiful. Record labels led by visionaries, and formed in their vision. XL wasn’t that, but it was a place that understood artists and it was all about their vision. I went into XL as a promoter, so it went from being about picking the acts and picking my vision and having this relationship for one night, to suddenly being an A&R, which is when you find the acts. That’s not about your vision, and it’s not for one night – it’s for 10 years.

Was that a natural transition for you?

I found it very difficult. You’re not aware that you need to make these changes until you make them. It was all about my ego and my vision. If it worked or didn’t work was all based on the quality of my idea, my work, and some circumstantial things. But when you work with an artist, you have to surrender quite a lot, because you are there to find someone you believe in and help them to get to the point where they can manifest their vision. You can help create an environment around them that gives them the best opportunity to do that, but you can’t do it for them. It was no longer my ego that was going to make it work. In fact, my ego became a massive impediment because you have to listen and I wasn’t very good at listening. I made some horrific mistakes and had some huge fallings out with artists early on as I was learning what I had to do to actually help them. The beauty of what we do, working with artists, is that not only is every artist different, but every stage of their career is different, and the people who are listening to the records also change.

When you started to run the record label, how many of the acts did you find yourself?

I don’t think I signed anyone. I can tell you who showed me each act. Artists do the work in developing themselves; they are not consciously sitting there doing it, but it happens naturally because they are compelled to make the work for one reason or another. And they get to a certain point of capability where lots of people at once will come across them, if they have put themselves out there enough. It’s like when an idea is thought and exists in a communal space, in the same way you might come across five people who make a scientific discovery at the same time. I don’t really believe in discovering artists, artists do a certain amount of work that churns up into the atmosphere and they’re going to be noticed. It’s not the unearthing of a rare commodity; it’s a ‘do you connect with them?’ But I’m not really interested in the work the artist has done – it’s more about the future. And that has come from observing the decisions they make, observing their process and talking to them, being curious and finding out from what position they make their decisions. Is it a unified artistic thing? Is it all flowing from the same source? Or is it a bit more scattered and not really pulled together?

When you started Young Turks, did you need reference points in terms of mentors or a specific direction?

It was too intuitive. I started the record label and it was really badly run for the first couple of years. There was no rhyme or reason, no direction; I was just signing things without any clue. XL had these classic record sleeves that all the vinyl went in, so it was unified. Warp had this perfectly curated sound, and at the time, there were also Hyperdub and Kode9. I was in awe because every bit was artistically done, and it all tied together. Every label I loved would be like that, from the classic American hip-hop and old soul labels through to the European and British dance labels. Even how Decca or EMI did their classical stuff. I was in awe of that vision and foresight. I just started it too early ever to have had that much forethought; I was too young with no experience. I learned from the things around me and from Richard Russell and Mark Mills who ran Beggars Group, and Ben Beardsworth who ran XL. The way they found the right artist and then protected that artist’s vision, so the artist could manifest their vision; that’s been my biggest influence.

Young Turks has that unified vision now.

One hundred percent. It is very different to XL, though, because it came in this period where the artists were doing a lot of self-development. If you wanted to start a band, you had to learn your

instruments, you had to find other people who wanted to be in a band, and had to agree on a shared vision, then rehearse and find some gigs, then find some studio time, record onto tape, record onto DAT, put it onto vinyl and get it into a store, or do enough gigs so that an A&R would see you and get you a record label. Then the record label would help you record an album, take you to radio, take you to press – and you would find your audience. And all those steps allowed for a really thorough development. Those artists had to make millions of artistic decisions to even get there. Every one of those decisions was like a deepening of their craft and was making them more profoundly interesting. Then the Internet and software turned up and you could just do a track overnight, put it online and reach an audience, and that whole development process dropped away. I learned the XL way, but I could never compete with them because they just did it better than me. I had to find acts that weren’t ready for XL and develop them, give them the tools to develop themselves. And that is now the vision of Young Turks: helping artists find their own vision. It’s the artist’s own journey and we provide support along that journey.

What do you think made those other labels so successful?

If Def Jam had existed in Lebanon in 1972, it wouldn’t have been the world’s first proper hip-hop record label. It was so reliant on the moment, the time and the people around them. I couldn’t have

started a rave label that was culturally significant in 2006 because it happened in a different era. Environments and cultural ecosystems clear the way for artists to blossom, so it is no coincidence that post-punk, hip-hop, disco and some bits of house music came out from a 20-block radius in New York in the late 1970s and 1980s. There was something going on in the way that society was structured and all the different cultural institutions that allowed for this explosion of creativity. You either happened to be there and capture it, or you were intelligent enough to spot it and go towards it. All the things that have linked these great record labels – and I imagine art galleries and editors of magazines – is that they had the luck to be around a place that was completely vibrant with brilliant people and they had the ingenuity to spot it. Beyond that, they were better than anyone else because they had a vision of what they wanted. And they went against the tide that was pushing them. This record label wouldn’t exist if we didn’t live in London; it would be different, because we are reacting to our place. Now on the flip side of that, all of those record labels made the place that they were in better. They made it more likely that an artist would appear from that place. Warp collected the best of the electronic scene helped inspire the next generation of electronic musicians, and Motown captured a moment in Detroit, while also putting Detroit on the map and helping the next generation of Detroit musicians come to the fore. I like that conversation between being there to capture something, but also doing something so special that you push the culture forward. That is what they did and the thing that links those people and labels is that they were all visionaries, and they could speak to artists and they were all willing to help make the artists’ work as good as possible.

Did you decide to go for a more spacious method because of your experience of working with XL?

The truth is that on my first day at XL, Richard pulled me into the office and said, ‘Alright now you’re in A&R, who do you want to sign?’ I had a friend called Kid Harpoon, and he was one of the best songwriters in London at the time. He was phenomenal live, charismatic beyond belief, and had wonderful guitar-playing and singing skills. I could have gone to his shows for years on end; it was really powerful. We took the train up to Manchester that week and saw him play, and I offered him a

deal. Before I got a job in A&R, I would speak to Kid Harpoon on the phone a lot, and I remember pacing very intently up and down the street where my dad lives, saying to him: ‘If I ever get into A&R, we’re going to go out and record just the rawest live show, the rawest representation of who you are. You’ve got it down – it’s perfect. Then we are going to tour that album and build your foundation and then we’re going to take the next step.’ And he was like, ‘Great, I’m onboard.’ But then, as soon as I had the record label and the resources, I completely lost it. And I got every producer ever to come in and was like, ‘We’ll make three albums.’ Two were terrible, one was OK, but it was nowhere near his potential. I was young. I didn’t keep things simple; I didn’t trust my instincts. We just spent all this money on stuff that wasn’t highlighting what was brilliant about him. Stephen Street, who produced the Smiths records, agreed to do the Kid Harpoon album. It was sounding awful, and I sat him down and said: ‘How come the Smiths records sound so good and mine sound so dreadful?’ Which was probably actually massively insensitive of me. But he said, ‘Look, I didn’t make those records; the Smiths made them. I just captured them. As a producer, I’m only as good as the act I’m recording.’ When Kid Harpoon and I parted ways, he handled it really well. He was probably in his mid to late 20s, and by the end of it I was probably in my early 20s. It was tough, but then he went off to become one of the world’s best songwriters. He had it, but I wasn’t tuned into what it was about him that was special. You can’t make things good with money and the decisions I was making were never going to be the right ones. It has to be the artist making their decisions, with you maybe bringing some good options for them to choose from, questioning their decisions or helping to reinforce their decision-making. It was very emotionally painful for everyone because it didn’t work out with Kid Harpoon. I spent a lot of the label’s money; it felt like a huge failure on my part, and I had an emotional collapse. The next band I met was The xx and I was like, ‘I am not going to rush this, no pressure on this doing well. I’m going to do this the opposite way; they can decide everything and I will just protect what they want to do. I won’t rush them. Instead of making an album, I’ll pay for their rehearsal space for two years and they can just figure it out and do it by just being.’ Everything was a reaction to how I had done it wrong previously. With The xx, we just found each other at the right time. No one was interested in signing them and I wasn’t interested in pushing an album. We took it slowly, being real, playing gigs, listening to music, experimenting with stuff. Then eventually Jamie [from The xx] suggested that he produce the record and we did a very small deal to make sure it was financially without pressure, no one was hyped for them. Everything was the opposite, that was like ground zero and about understanding how to move forward. That was when I realized that this was how I wanted to run a record label.

It is hard to take that step back, because the world moves so fast. How do you know when to slow down?

I am so unbelievably privileged in the grander sense that I was born in a city like London, and in a smaller sense that I had parents who understood the value of working with artists. Not to mention in the more pertinent and precise sense that I was losing these guys loads of money and they stuck with me, no one ever rushed me or demanded that I make a big return on my investment. Everything just evolved the way it could. You just had to do a good job along the way. At any other company I would have been sacked; with any other mentor I wouldn’t have learned those lessons and I would have been hurried into making more mistakes. I am eternally thankful for that. We have gone on to work with lots of other artists over the past 10 years. We’re coming up to 10 years with Koreless and he is just about to release his debut album and it was well worth the wait. He has done beautiful artistic things in the meantime. If he wasn’t such a radiant joy to be with, we probably wouldn’t have carried on, but the space that I have allows us to give space to the artists. Sampha took seven years before the album. The xx was two and a half.

What do you do in the meantime?

You try to etch out a faint outline of what they want to create, and if they are not ready to do that right now, you try to find the pathways that allow them to develop the skills to do it. Sampha wrote

and produced for a lot of people, and in doing this he learned from them about how to be an artist. It allowed him to fill his time with productive things that kept him patient, and as a human being he

became ready to express what he wanted to express. It gave him an audience and it allowed his audience to be patient with him and it made him financially secure. So that is a very clear pathway.

Sampha always wanted to be very true to his personal experience and his personal experience was very painful, so he didn’t feel ready as a human being to make his artistic statement. The xx just didn’t play instruments; they hadn’t had a chance to rehearse. For them, it was more about the live experience and sending them on tour. Learning how to sing, learning how to perform, which still took them many years to master. Each artist is very different. FKA Twigs was very good at the visuals early on, very good at all the things that went around it, and in that period she learned to produce and to engineer; she mastered several different types of dance; she spent many years as a singer in a jazz bar. She developed all the technical things she needed as an artist, while waiting for the centre of gravity of her taste, and her ability to express unique things and intertwine the different influences in her life in such a unique way.

And you bring in ideas such as, ‘Why don’t you collaborate with Grace Wales Bonner, so that brings something to your world…’

Exactly, you tune into what you think they already want to do, and then you can suggest particular things. What tends to happen is that they will be talking about life, you engage them on a subject, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, my friend is making a film at the moment and I loved it, I would love to do the music for that.’ So you say, ‘Why not do it then?’ You help empower decisions and things they want of which they don’t think they’re capable. That’s when the best stuff happens. Just putting them in a world that will inspire them, making sure they are an active part of an artistic community, so they create the connections from which they can collaborate and express themselves. We put Grace Wales Bonner and Sampha together because I was lucky enough to meet Grace years ago, and we had lived together. Grace could help Sampha with visuals and Sampha could help Grace with realizing what she wanted to do with sound. The real beauty in that is bringing the two minds together and all the incidental things that they created. Romy from The xx went to Saint Martins to do a foundation course, for example, and a lot of those people ended up working with her along the way. We met just as she was leaving school and then she went to Saint Martins. Often the community the artist needs is right in front of them and it is just about empowering them to go for it, and then helping to nurture that community so they all succeed. That is the ideal. Some artists don’t have that, so we have to suggest one, but it has always been for an artist to back themselves. I’m not here to work with an act just to make their next record better; I am here to work with acts for their entire careers. I don’t want one-hit wonders or a flash in the pan. I want the acts to last, and for them to do that, they have to develop themselves. And collaboration is one thing, but you still need to drive it home. The idea is one thing but the execution is completely another. Someone had the idea to get Jamie xx to remix Gil-Scott Heron’s album. That’s a good idea, but Jamie then had to go and make the great album.

What are the important factors for an artist’s longevity?

You have to create a life and an environment around yourself that allows you to be the truest version of yourself – and the artists, whatever they do, who I have found doing their best work completely follow their bliss, from who they have lunch with to where they go on holiday to how their house looks, to the distribution model by which their work goes out. It is all dictated by them following what they enjoy, who they are, and what they love. When they get distracted by industry pressures or money, that is when they start second guessing themselves. To do that, though, you have to create an environment that allows them to make those decisions. If you are surrounded by people who are forcing you to make commercial decisions 24/7, you will make commercial work. If you are doing things on a personal level for any reason other than the thing that you are trying to create and the joy it brings, you will probably lose sight of what’s important quite quickly. And that often means having complete control. Not being a control freak, though, because they tend to want control of things that don’t matter. But if you can have sovereignty over the things that are important, then you can start to make a series of really good decisions, and make work that you want and that will allow you to stay in tune with yourself. That is what I would say, and now a part of that is creating the financial freedom to do that, which comes from two things: making enough money and not needing that money. Some of them get distracted, but then we all get distracted; it’s a natural thing to do. Only the very best can stay focused on what it is they want, even if it is unpalatable to other people.

You spoke about the growth of your artists, but what about you? Do you have a vision in mind for yourself?

That’s a very interesting question. [Long pause.] I want to get this right. The key thing I want to be able to do is to keep adapting. If I were an artist, I suppose my dream state would be always to be able to make work, to continue to create work. And if you’re able to continue that, then you’re getting it right. I would like to be able to continue to work on an artist’s behalf, and with the world changing as rapidly as it does, that requires a lot of growth. So I want to be better at understanding what our artists need as they change. And I want to improve how we help our artists to communicate with the world. More than ever, you need to be creating things that are ancillary to the work itself, to create a world in which the work is presented. I want to be able to make films, publish books, and put together different types of performance from music to dance, to help our artists communicate what they want to communicate. I am in the business of working with people who write the future. I do wonder if we’re not heading more into a freeform state, into a moment of cultural improvisation, as opposed to grand schemes. Where artists who can just live in and respond to the moment will be able to communicate their thoughts much more successfully than those with grander visions who slowly think about what they want to do. Even if my gut feeling is that both have existed, and both will continue to exist. The more people doing things spontaneously, the more important it will feel when someone gets together with a well-thought-out, slowly created masterpiece.

What are your thoughts on how the music industry itself is changing?

One thing I’m excited about is that domestic and local music is on the rise worldwide. People are listening more to music that people around them are making. That’s an exciting celebration of local cultures, and although some things will become homogenized and sound similar, how things are made and the detail behind them speak very locally. Even in London, a lot of the most exciting music that’s coming out emerges from extremely local scenes speaking to themselves. Take something like drill. The language is very closed in on itself; it’s almost like a code and what they’re talking about is very micro happenings within their world. I think a lot of people, myself included, thought the Internet was going to completely globalize everything. Now you know that they’re using beats that were made in Chicago that they’ve taken and made their own, but it’s completely different to what’s happening in other parts of the world with hip-hop culture. Yes, the Internet has connected us all, and at first it might have destroyed the boundaries between genres, but now I think we have a chance for culture to become a little more local again.

We haven’t talked about fashion yet.

Fashion… When we look for pathways for an artist’s development, they need to be able to bring opportunities in which to experiment and to express themselves, but quite often there’s a limit to how much a musician can do with other musicians. Over the years we’ve realized that what we want to do is bring brilliant minds together to affect both in their separate disciplines. Sampha made the Process film with Kahlil Joseph. It is a beautiful film and Kahlil helped Sampha express something that he couldn’t express in the album. But beyond that, the two of them, how they observed each other’s work, and how they observed each other’s philosophy, massively helped them grow. So, you go to other brilliant people wherever you can find them and you learn from them. Fashion has always looked to music and vice versa. The story of popular music is tied up with social movements, and

social movements are defined by their fashions and their music. The two just live interlinked. You get someone like Raf Simons working with The xx and Raf is clearly a brilliant mind of his generation; there’s a very strong thread running through everything he does. You can learn from collaborating with him. As much as I am inspired by the way that fashion can pull from lots of different art forms, and how it is constantly recreating itself, I am more interested in the people in it, and what they can teach musicians and vice versa. What they get from that discussion is more exciting to me than just an artist wearing a designer’s clothes.

Fashion seems to have become a patron of the arts in the way that the Church was in medieval times, when it financed the greatest artists. Now it is fashion brands with the money and desire to work with and ‘own’ cultural leaders.

Much of what we feed the audience from an industry point of view is visual, and so much of that visual is fashion. Fashion brands have a hold. In a certain way, they are like the gatekeepers of – for want of a better word – ‘cool’. So when much of an artist’s output is visual and fashion brands have such a stranglehold over the visual, fashion has this huge sway over music. Yet the actual music being made is not really being exploited by the fashion industry. The fashion industry has always supported interesting people and musicians in an interesting way, from Marc Jacobs bringing Sonic Youth onto the runway through to Raf’s love of The xx through to Hedi Slimane’s love of music. Fashion can be a huge supporter of music, and it has often ringfenced people who it thinks have a strong visual identity, and in that way, it has been an incredible patron. Music is a beautifully democratic format: you make your money by the most amount of people paying the same amount of money for your thing. If you want a number-one hit, you need everybody, and everyone counts as one; unlike fashion, which is about building a myth and then selling it to a few rich people. In that sense, fashion’s ability to have a stranglehold over what music does through money is not a great force. But the way that fashion dictates, the way that musicians look and therefore present themselves and therefore think, is extremely powerful. And despite it being a couple of old French men owning most of this global fashion, there are thousands of artists referencing these brands as if they have just discovered them. It is not direct patronage, but more through its influence. Every single popular music artist who displays their image is doing a massive part of it through what they are wearing, and the more counterculture you go, the more connected to fashion it becomes. Every social movement that had a musical movement created fashion. They all feed into each other, the high and the low. In the same way that a young designer is ripped off by a bigger designer and a bigger designer is ripped off by a high-street chain, but then it comes back round, and that little designer was actually using a vintage piece from that chain – the whole thing is cyclical. The way music and fashion correspond is completely the same. Like how Odd Future came out with their unique mentality that rejected everything that had come before, while also respecting it all – and that was distilled in what they were wearing. Before kids understood the jazz that was behind Tyler’s music, they felt the punk through what he was wearing. Ultimately, fashion has had this huge knock-on effect on what kids are doing societally and musically – the two are so completely intertwined.