How has master milliner Stephen Jones managed to work with so many different people over extended periods of time, quite often simultaneously?

By Tim Blanks

Photographs by Juergen Teller

How has master milliner Stephen Jones managed to work with so many different people over extended periods of time, quite often simultaneously?

Stephen Jones grew up by the seaside, near Liverpool in north-west England. His school sometimes had sandcastle-building competitions. He remembers one, when he was seven years old. He and his friend Mary had spent some time planning a winner, but then the kids next to them built the Taj Mahal out of sand, and decorated it with shells. Stephen and Mary’s effort looked unsurprisingly meagre by comparison. Quick thinking was called for. Young Master Jones whipped out his white cotton handkerchief, ripped it into four squares and draped it on his sandcastle. ‘It’s the Taj Mahal’s laundry,’ he proudly announced. They still didn’t win, but they got the laugh. And there you have an early lesson in putting something on top of something else to make it look better, more charming, more entertaining.

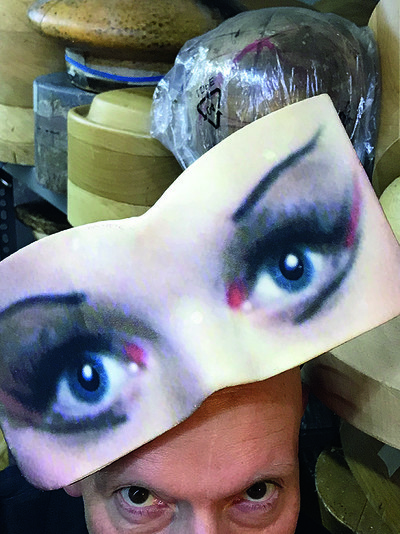

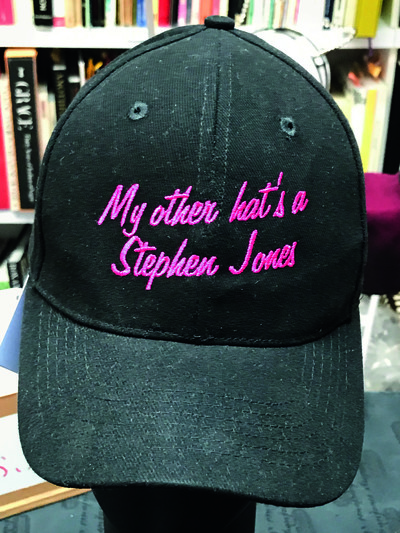

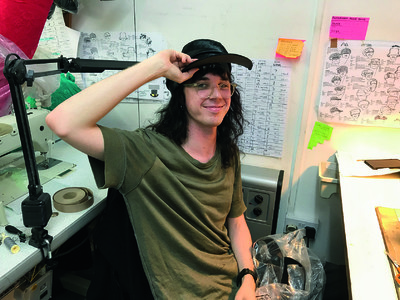

He’s still doing it nearly 60 years later. Is there anyone for whom Stephen Jones hasn’t made a hat? Is there any scene that he didn’t move through – Blitz to Buckingham Palace, Aspen to Ascot, Margate to Mars – Zelig-like, in his four-decade ascent to the pinnacle of his profession? I could talk to him for days and still feel I’ve barely scratched the surface. Not long after the conversation that follows, he was set to embark on a seven-day Atlantic crossing with his husband Craig West, New York to Southampton on the Queen Mary 2 for Cunard’s annual Transatlantic Fashion Week. In a nutshell: ‘100 hats, 19 models, 15 girls, 4 boys. They don’t change, but their hats do. And I’ll be talking.’

Maybe that’s what I really need. Cast away on an ocean with Jones talking and nothing else for me to do but listen. For now, I have to make do with one summery Saturday at his shop in Covent Garden.

Tim Blanks: Let’s go back. Where did everything start?

Stephen Jones: Everybody’s childhood is normal when they are growing up because that is all they know. However, having said that, I knew I was a bit different because I had three fingers missing on one hand. I absolutely never had a problem with it, but other people did. What they think is that my mother’s umbilical cord got wrapped around my upper arm – I have an odd line there – and so my fingers couldn’t develop. That is one theory. The other theory is that at the children’s hospital in Liverpool in late 1956, which was where my mother was going as an outpatient, they were doing various experiments with radon isotopes, which were supposed to ease the pain of childbirth. I just happened to read about this on the Internet, and I worked out that, yes, it was that hospital and yes, my mother did go there and it was exactly at that time. Funnily enough, all the hospital records have been lost from that period. I asked my mother about it, and she couldn’t talk about it, but I think for any parent from that generation who had a child who was a variation from the norm, they were brought up to think it was a problem to be concealed. Though they never ever showed that to me. I remember my mother saying, ‘You have a strange hand, but some people have strange brains and that is much more serious.’ However, I guess it did mark me out from other people.

And other kids can be brutal.

Well, it was never an issue for me. I went to a nursery school, which was a state school where my sisters had been, but I wasn’t doing well. I can’t remember if it was to do with my hand. But anyway,

when I was six or seven, I was sent to a private prep school in West Kirby, which my mother had attended. And that was great. I made friends there that I still have. We would talk about television, this whole window to another world, which was the most exciting thing in our lives. Though I loved music, too. Any music. Apparently when I was two or three years old, if my older sisters wanted me to be quiet, they would just put a record on and I would dance for hours. Literally hours. And they could get on with snogging their boyfriends behind the sofa or whatever they were doing. But at school, what we talked about was TV shows. It was all space exploration, and Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s puppet shows like Stingray and Thunderbirds. With my friend Larry, we used to imagine that we were the characters in those shows. And in a way, that was our reality much more than anything else, up until we were about nine: I was in a TV series and I was a puppet. Years later when I first met Jeremy Healy, his name for me – and many people’s name for me – was Lady Penelope, because they thought I was posh. Which I vaguely am, but not really.

Well, you do have incredible manners.

Which comes from being at prep school and boarding school. So that was me as a little boy. Not family, not sports. Living in TV as a science-fiction puppet.

‘Any post-war-generation parent who had a child who was a variation from the norm was brought up to think it was a problem to be concealed.’

I know you did Lady Penelope’s hat later on for the movie. That must have been a full circle-of-life moment. But were you interested in science at all?

I love science. In fact, when I went to boarding school, the master who had taught my father in 1938 was still teaching, and he taught me physics, which was one of my best subjects. My father was an engineer. The management of stress and strains was a very big part of what he did, as it is for me.

I’m obsessed with the idea of manifest destiny in people’s lives. The nature of so many of your hats is aerodynamic, and the idea that you might have a genetic predisposition to that…

True, I like my hats to be aerodynamic, and other people’s hats throughout history, in terms of solidity and weight and majesty, have each done different things. It is so funny that you touch on that because it is an idea that was quite strange for me when I first heard about it maybe 12 years ago. I remember people saying how Saint Laurent doing the blazer guided the way we look at fashion so completely that we can no longer see that how we view fashion is through the vision of Saint Laurent. It is funny how, being 62 years old, I am now experiencing the same thing. That the world of hats is seen – certainly on this side of the Atlantic – through Stephen Jones and what I have done. Valerie Steele told me this. There’s a school of Stephen Jones in London and a school of Lola in New York, because so many people have trained with her and with me. It’s sort of flattering, but it’s also unnerving, because it makes you want to get on to the next thing that is aerodynamic and light.

How many hats have you designed in your life?

Probably like a hundred thousand.

I remember once you mentioned you didn’t like the idea of being described as prolific.

Prolific is somehow the opposite to the idea of exclusive. If I’m prolific, it’s because I have to be, in a funny way. I have to do turnover and make payroll and run a business and so I have to produce a lot of things to make the whole thing work. But at the same time one of the big design things I have learned is do a lot and don’t over-analyse everylast thing because then you kill it. Actually, it is much better to move onto the next thing and put the previous experience into the next thing, so you can get on and do something fresh rather just reworking it and reworking it.

It’s an intriguing psychological twist that you’re so devoted to curating exhibitions dedicated to hats. Did you ever think about designing for posterity? How many of those hats ended up in a museum rather than on a head?

I have never ever designed stuff thinking, ‘Oh, that will be great in a museum.’

But now you know there is a world of hats ‘seen through the eyes of Stephen Jones’, does that bring in a self-consciousness that wasn’t there before? Now that you can see yourself through other people’s eyes.

It would be disingenuous to say I don’t. That is in the background, though, and when you are designing a new collection, you are doing new things that you hope are going to be worn by people. You are not designing for posterity. Completely aside, I had some fantastic news yesterday. My Winter 2018 collection was called Crowns and was based on African-Americans’ love and understanding of hats. At the time Pharrell was being called out for wearing a Native American headdress, I thought, ‘I understand why this is going on, but at the same time to my mind it is completely ridiculous.’ The reason you go to another culture for inspiration is because you like it and you respect it in the first place. If you didn’t you wouldn’t be using it, durrrrh! So, when I was planning this collection, I spent two days with the curators at the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington to really research it. You go into a room with these women and they’re all in their 50s and 60s and you wonder what journey they had to make to get to such positions of cultural and political power. I said to the director, ‘Wow, this is such a big building, the White House looks very small from here.’ And I mentioned that I didn’t think much of the present occupant. She said, ‘Mr Jones, that’s why the blinds are closed.’ I asked, ‘Why? So you can’t see out, or he can’t see in?’ She said, ‘Both. And it will stay that way for the next few years.’ And that broke the ice. So yesterday, I had a phone call from the senior curator there, and she said they would like to buy the Crowns collection from me in its entirety. I almost cried.

What did they know of you before?

They knew that I was a famous hatmaker working for Christian Dior and they were surprised from afar that I would show interest in them and their museum. I think they are all a little bit surprised to see how popular it is.

Do you think that whimsy can survive in a multicultural society when it is so intrinsically English?

I think whimsy can be from anywhere.

When you talk about it, you isolate it as something distinctively English in your work, as opposed to the work of Italians or the French.

Oh yes, absolutely. But that is its charm. Slightly failing. And not trying to be too polished.

And incredibly idiosyncratic. With your obsession with sci-fi puppets, at what point did design enter your consciousness? Because those shows were super-designed.

It was really just this fantasy about going off to a different place. It was a set; it wasn’t real life. I mean, my real life was a nice middle-class family and a nice house. I had a fantastic view from my bedroom window: a small road and then the sea. And on one side, on a dark day, you could see the flickering lights of Liverpool and on the other side, the Welsh mountains. So the one thing I did experience was this ever-changing beautiful landscape of nature, and this fantastic panorama. I could see the waves coming in like white horses, boats coming and going, a lighthouse, a lifeboat man, the whole thing of growing up by the sea until I went away to boarding school at 10 or 11.

Growing up by the sea does infuse you with a sense of possibility.

Yes, and combined with Stingray, it’s going to do things to a young guy! Even though I didn’t know what it was then. Probably a little gay boy, knowing he was a bit different. I don’t think sexuality is formed completely at that age, but I think there is a sense of a range of possibilities, which focus as you get older.

With all of that going on, you headed off to boarding school in 1968. How on earth was that?

Fairly draconian. It was very much an old-fashioned 1950s institution. I was considered a sissy in as much as I liked art, which at my school was enough. It was beyond the pale. I was at the same school my father had been to, and he had been captain of the rugby team in 1938 when he was in the upper fifth, let alone the lower sixth. So he was a legend, and if war hadn’t come, he might have played for England. He was a great sportsman. So, of course, they thought I was the great hope, but you learned how to do it. I played hooker on the team.

You weren’t bullied though?

I don’t know. Was I bullied? Not really, the bullies would probably pick on someone weaker. I found out how to live through it, and also I just sort of sidestepped the whole thing, because I would just say: ‘Well, I am going to do some art or music.’ There were other things going on which weren’t approved of, especially Roxy Music and David Bowie, as you can imagine. Everyone else was into Yes or Emerson, Lake & Palmer. But I made some very good friends there and we were very supportive of each other. My friends Richard and Andrew, I’m still friendly with now. There were three of us doing art together and we taught each other. Bizarrely enough, the head of rugby was also the art teacher.

What drew you to art?

I was always quite good at it. I didn’t really have to think about it. It just seemed to be genetic somehow. My father was an engineer and very good draughtsman as well, which I discovered years later. My mother had a real sense of eye and colour and proportion.

Did she make her own clothes?

No, no, no. She wouldn’t do anything like that. Or housework, even though it was quite a neat house. What she loved was gardening; she was a fantastic gardener. She would take me around gardens and art galleries in the north-west.

Do you remember your first trip to London?

I was with my father. I must have been six or seven. I don’t really remember much about the trip, but I remember we went to this café… it was called the Sands, and I think it was done in 1960s Persian. Like I Dream of Jeannie. It had a gold awning. For me, this was unbelievable. We went up to the first floor, and the steps had illuminated glass bricks set in concrete and they were illuminated from underneath, turquoise and emerald green and blue-ish colours. This was a real turning point in my life. I remember the waitress came over and asked what I would like and I said I would like a Coca-Cola and it came to me in a glass with cubes of ice and a stripy straw and a slice of lemon. I had never seen anything like it in my life! Then I realized the possibilities of life! Just that idea that you could take this very normal thing and make a fantasy out of it…

‘I walked into Saint Martin’s and on this side was a group of girls wearing beige. On the other side were five punks. So it was, ‘Do I turn left or right?’’

Was that your Rosebud moment, the Coca-Cola with the ice and lemon?

I don’t think there was one Rosebud moment. It was a series of things, because it has been a sort of slow build. It wasn’t like I ever came to a junction and asked myself, ‘Do I turn left or right?’ I started on a different road from the word go. I only realize that now. And what is that, determinism? Is it genes? Is it circumstance? I don’t know.

Could it be simple ambition?

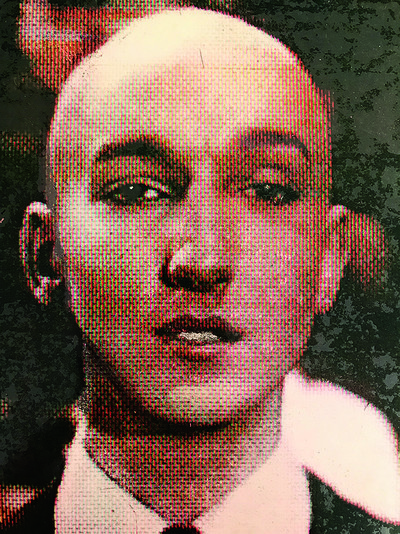

No, no. I’ve always said I was the least ambitious person that I knew. It is just a bloody hat – I don’t want to change the world with that hat. And I don’t believe that every woman should be walking down the street wearing a Stephen Jones hat. But dress designers have to have that ego, that clear self-belief which says, ‘I am right.’ And it is actually very, very funny and very interesting to see when people tell them that they are not right, or even call their judgement into question. They have to be that clear or they’d never be there in the first place. I was not ambitious; I was a late starter, and there was just a whole series of things. Actually, there was a very specific moment when I did come to a fork in the road. On my first day at Saint Martin’s in October 1976, I walked into a room and on this side was a group of girls all wearing beige – it might have been cashmere but, as far as I was concerned, it was tweed – and they were all from the south-east and a lot of them had done the foundation course at Saint Martin’s. Then on the other side, there were five punks. So it was, ‘Do I turn left or right?’ I turned towards the punks; I saw that was the future. I didn’t think those beige people knew anything about fashion anyway, or at least not the fashion that I was hoping for.

And who were you at that point? Were you raw clay waiting to be moulded or did you have an image?

I had an image. Like a Left Bank punk look. I was wearing a black turtleneck with black jeans and a black beret and chipped black nail varnish.

Did you have hair?

Yes, I think it was dyed blue-black, like Bryan Ferry.

Did heads turn when you walked in? Like, ‘Look at the new boy’?

They looked, then carried on talking. If my look was strong, it didn’t really fit in with either group. So I went over to the punks. One of them was a girl called Sían. Black denim jacket, white shirt with a black shoelace tie. Doc Martens, which I’d never seen before. She had a number-one buzzcut, which was completely shocking. Out of her top pocket was hanging a tampon on a string and she’d coloured the end with red magic marker. If anyone did that now, people would freak out in the street. Or at least men would. But it was just so funny. And there was another girl, Chrissie, who I’m still friends with. She was dressed like the Queen, in a big rose-print taffeta ballgown. I think she was wearing it over jeans. Sían asked me if I wanted to come for lunch with her and her boyfriend, so we went to this place called Soho Market, just off Charing Cross Road. And her boyfriend was Shane McGowan from The Pogues. I very occasionally see him now and we still remember each other after all these years. So there were Sían and Shane, and that was my first day at Saint Martin’s. There was another girl called Eve and she was going out with Adam Ant. Adam and Eve.

If this was October 1976, the Sex Pistols had already played their first gig at Saint Martin’s.

Yeah, and they had already played at High Wycombe when I was doing my foundation course there. While I was finishing boarding school in Liverpool, my parents moved to Marlow in Buckinghamshire, so I went to the local college in High Wycombe. And that’s where I saw the Sex Pistols.

I’ve always said I was the least ambitious person that I knew. It is just a bloody hat – I don’t want to change the world with that hat.’

And what happened?

It was a disaster. They came on late, they played two songs, their equipment stopped working. Everyone from the students’ union wanted their money back. It was a nightmare. Johnny Rotten had been on the front of the papers, so I knew that was brewing when I got to Saint Martin’s. With not much design tuition happening at college, that was what the focus was on. We actually formed a band, with Chrissie. There were six of us and we were called Pink Parts. My friend John was the lead singer and a completely electric performer, like a teen pop star. He had that absolute charisma. He went on to work with Spitting Image and made the puppet of the Queen. Martin was a fantastic musician. He went out with Ruthie, our bassist. He became an antique book-dealer. And Paul Ferguson went on to become the drummer in Killing Joke. And there were three backing singers. I was one of the singers.

Sounding like?

Sort of like the Supremes, because we were all singing in harmony. We definitely had a sound.

Did you have record company interest?

Yes, we did. We supported Wayne County quite a few times. We did the 100 Club; we played the Nag’s Head at High Wycombe, which was the biggest venue outside London for punk bands.

Do you have any tapes?

No, I don’t, but I know someone who does. We were recorded in the 100 Club.

How long did Pink Parts last?

About a year. At the end of my first year at Saint Martin’s, we had to decide whether we were going to carry on being singers. You know, trying to rehearse once or twice a week, writing songs; it was a commitment. We had about 10 songs of our own and we did covers of other people’s songs. I wonder though if we’d been better musicians and if we’d had more practice…

Maybe you’d never have made hats.

I would never have made hats. I was never sure if I was a punk trying to be a fashion student or a fashion student trying to be a punk. I think ultimately, I was a fashion student holidaying as a punk.

But wasn’t punk an art-student thing anyway?

No, I think punk was, at the very beginning, a mixture of different things. It was definitely club life, it was definitely gay, and it was a previous generation. I really do believe that people like Duggie Fields and Luciana Martinez, were sort of proto-punks. They were the people that we all looked to. And certainly Vivienne [Westwood] and Malcolm [McLaren] looked to them for inspiration. Vivienne wouldn’t particularly want to say that she was influenced by Luciana and Duggie, but they were into that really 1950s glam, which was such an essential part of early punk. I saw an article on them in my sister’s Honey magazine – I must have been in the lower sixth, at boarding school – and I thought when I grow up, I want to be like that. I really did. They were such extraordinary, fun, extravagant people. The funny thing is, I know that the story of the Blitz Kids is that we invented our media because the established media didn’t want us, so it was i-D, The Face and BLITZ, and all that, but it was under the umbrella of Luciana and Duggie, and Andrew Logan and the Alternative Miss World contest, and Zandra Rhodes, and Divine and John Waters, and they were London’s glitterati, and when they saw us, they took us along for the ride. They were probably 10 years older than us, but we got on with them because we looked fabulous. I mean, Luciana showed me how to get into a club and how to blag a drink. A very, very important guide to growing up.

I think the first time I ever saw Steve Strange was at the Embassy in 1978. He was with Zandra and she would always have this gang of incredible-looking people with her. He was dressed like a frontier scout in buckskin and fringed boots. And Jasper Conran must have been 17 or 18 and he was dressed in a sailor suit like Tadzio in Death in Venice, with a big pearl necklace on. I loved the Embassy, it was so much more fun than Studio 54.

You went on roller skates and wearing hot pants, I hope. When I was at college, the Embassy Club was always somewhere quite magical. Sure, we knew the Vortex24 and the 100 Club and the punk clubs, but in 1978, 1979, the Embassy Club was full-on glamour and it was always really difficult to get in. The door bitch didn’t want fashion students hanging around. Me and my friend Susy would basically solicit members at the door. And sometimes we did get in. Don’t forget the background of all this: the Winter of Discontent, all the strikes, huge mountains of rubbish in Leicester Square, rats everywhere. There was Peppermint Park as well, and Joe Allen’s. So there was all the Americana that was somehow coming in, and all that Miami pastel thing. We didn’t know it then, but it was really the beginnings of post-modernism. What we were up against was a great big eiderdown made out of brown tweed – and what we really wanted was Amanda Lear on the cover of For Your Pleasure. Last Friday I saw, for the first time, a film of my final fashion show at Saint Martin’s. Prince of Wales feathers made out of dead seagulls. The press wasn’t allowed into the Saint Martin’s shows in those days, so the show had been filmed. And I used the song on the flip side of Roxy Music’s ‘Ladytron’,

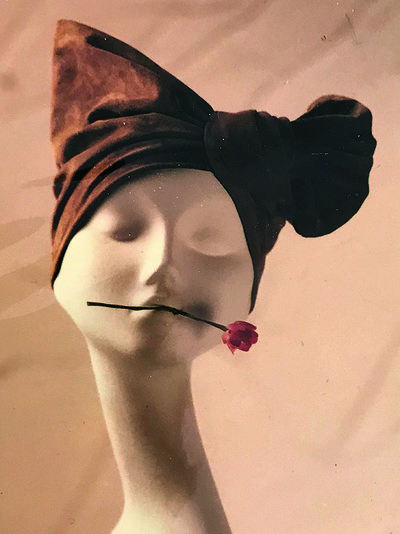

which was this weird dirge. I learned some things at college but I didn’t learn design at all. I still can’t draw a hat. You can’t really be taught design; you have an interest in it and you channel it. I learned mostly from the old issues of Vogue in the library. There was a huge box from the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, that no one was interested in. When we were told to go to the library to do research, most people thought that was an excuse to have a glass of wine. But I loved those old Vogues.

Was anyone doing hats at Saint Martin’s in those days?

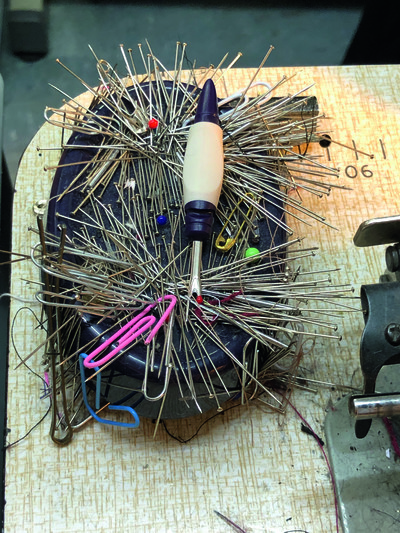

No, no one. David Shilling was the only milliner of note in London. I didn’t really have a clue what I was going to do. My tailoring tutor Peter Lewis-Crown said I had to get extra help, so he sent me to the fashion house Lachasse as a tailoring intern. Internships were called work placement in those days.

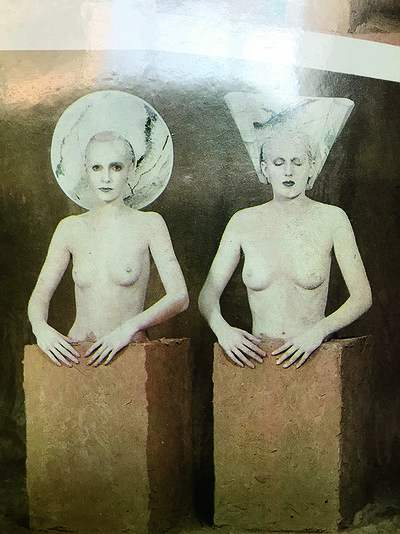

I couldn’t really sew, so I made coffee and picked up pins. Shirley Hex was the head of the millinery workroom. That was the eureka moment for my life in hats, because the hatmakers seemed to be having so much more fun than the dressmakers. The biggest change was the beginning of my third year in 1978, when this group of really interesting people came into the first year: Stephen Linard, Kim Bowen, Lee Sheldrick, Fiona Dealey, Sade Adu. They all had a really interesting point of view and they all looked amazing. Suddenly there was this whole new energy from people two years younger than me who were absolutely not punks. They were more connected to people like Duggie Fields. It was Dinny Hall and John Maybury and Cerith Wyn Evans. And I became friendly with them. I remember at a gig at the London College of Printing, I went up to Kim Bowen and said, ‘I like your earrings.’ That was my pick-up line! They were made by John Sellers who was a student at the Royal College of Art. He did all the invitations for Andrew Logan’s Alternative Miss World, and he went on to form textiles company Hodge Sellers. They became great unsung heroes who did the textiles and prints for Azzedine Alaïa, and worked extensively with Louis Vuitton and Chanel. Anyway, he made these black plastic earrings for Kim and they were sort of New Wave, and life was changing again, with the Next Big Thing coming along.

‘In my first shop, I was selling to everyone from the wife of the governor of the Bank of England to Lady This and Lady That to a Russian hooker.’

You must have been making hats by then?

Yes. But I wasn’t really wearing them. When I left college, I was still making women’s clothes, and hats were just an extra. I went to Paris, tried to get a job. I actually went for a job interview with Madame Grès, number 1, Place Vendôme. When I arrived, I told the secretary I had an appointment. She said, ‘I don’t think so.’ I insisted I’d confirmed it. She made a phone call, then said, ‘I’m sorry, you don’t have an appointment here.’ I realized that, because there were lots of mirrors in the showroom, Madame Grès could see from the far end of showroom. I guess she didn’t like the look of me, but I loved what she did at that time. Oddly enough, she was the aunt of Sybille de Saint Phalle, who became my first assistant, and went on to become John Galliano’s first assistant in 1984. I arrived back in London with no money. I had to give up my flat and went to work for my father driving a truck as a fruit delivery man. In the evening, I made hats for Kim Bowen. I came down to London one day, opened up the back of my car and said, ‘Kim, here are 15 hats for you.’ This was Spring 1980, a yea after leaving college. She wore them out and about, and Steve Strange saw them. He was working in P.X., which was just in the process of moving from James Street to Endell Street in Covent Garden, and he said they had a basement they weren’t using and asked if I’d like it. So, on October 1, 1980, I opened my own little shop. It went really well, selling to all sorts of different people, from the wife of the governor of the Bank of England to Lady This and Lady That to a Russian hooker. Then the financial arrangement with the shop changed and I went to work in Wardour Street. Boy George asked me to be in the video for ‘Do You Really Want to Hurt Me?’ I was wearing a fez and when Jean

Paul Gaultier saw the video, he asked me to model in his first men’s fashion show. But I fell off my brother-in-law’s motorbike and I couldn’t be in the show. When I visited Paris a few months later,

Jean Paul showed me a film of it and asked me if I wanted to do hats for his women’s collection. On that same trip, I went to visit Azzedine Alaïa in Rue de Bellechasse. Azzedine quite looked after me. I only found out many years later he’d had lunch with Joseph and told him he had to buy my hats for his shops around the world. That started my wholesale business, just as Bloomingdale’s was starting to buy them, too. Azzedine loved what I was doing but he wasn’t showing at that time. So he sent me to Thierry Mugler. I worked with him for a couple of years. We were really close; we’d hang out when he came to London. Claude Montana had been asking for a few seasons if I could make hats for him and I’d turned him down. Then he said he was going to do a men’s show and could I work on that? I tried to call Thierry to see what he thought and I didn’t hear so I sent him a letter by recorded delivery, still didn’t hear anything. When I was in Paris a month later, I went to Mugler. I knew everyone there. I waited a couple of hours, but Thierry wouldn’t see me. Eventually, I got a message that he would call the police unless I left. So I went to work with Claude. And I worked with him from 1986 onwards, for 15 years through the apex of his career, at Lanvin as well. It was extraordinary and wonderful to see the mastery of technique, the elegance of things he created, and I also saw how it all went wrong. He was drinking, going out too much. Béatrice Paul, who was his contact with the outside world, told him to calm it down. He didn’t like that, and she left. And then slowly the walls came crashing down. Fashion was changing and he didn’t change with it.

Where was John Galliano while all this was going on?

He was the class of 1984. He was quite a bit younger. Colin McDowell said he went to the Blitz, but I think he was a bit too young.

I could swear that I read you met John at the Blitz, he asked you to do hats for him and you said no.

I doubt it. I don’t really remember John asking me to make hats. The first person to make hats for him was Shirley Hex, the lady who taught me, and then Bouke de Vries made some hats for him. That was when I said no. And then Philip Treacy made hats for him one season. And then I introduced Steven Robinson to John. Shirley was teaching millinery at Epsom School of Art. She asked me to go down and judge a hat competition. There were all these crazy hats, but there was one tiny pink boater, so well-made and mannered there was something neurotic about it. I gave it first prize. I asked the winner – it was Steven Robinson – if there was anything else he wanted to do, and he said he wanted to work for John Galliano. So I asked John if Steven could intern for him, and within a week, he was John’s Svengali. And then, one day years later, I had a phone call from Steven. John was already an icon; he was the It person absolutely, and he was doing great fashion shows. My first with him was Princess Lucretia, in 1993. It was a totally different situation from Claude. Suddenly I could express my quirky Englishness in a way I never could do before. The real magic of John was that he had Steven and Bill Gaytten working with him. John would say the story is a Russian princess running from wolves; Steven would imagine fabulous accessories and work with Manolo [Blahnik] to make shoes; and Bill would work on the cuts to turn John’s inspirations into clothes. That was the magic about having the three of them together.

Was working with John your most productive partnership?

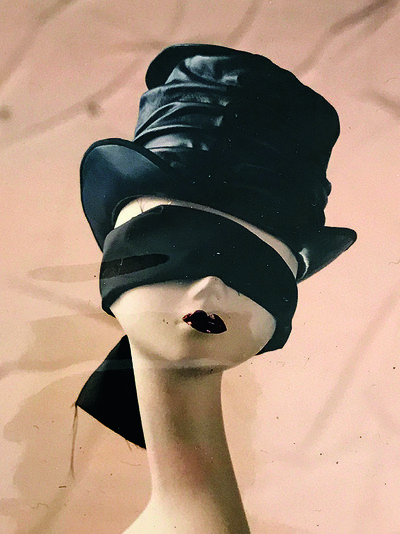

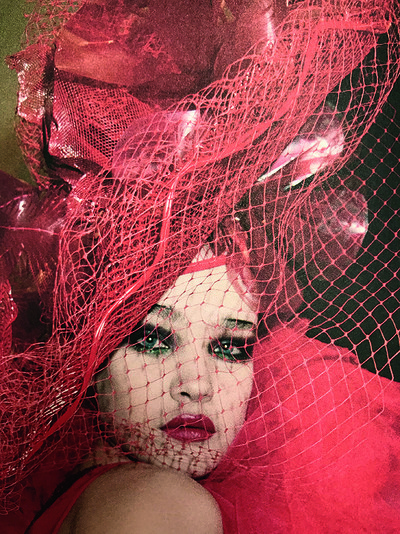

Yes, I think so. I always think the most productive partnership is the one I have now, but the hats that John and I made together were often extraordinary, and certainly have gone down in fashion history. I talk about the transformative thing that happens when real people wear real hats, but when I was making things for a Galliano fashion show, that was a different brief. It was not about selling or reality, it was just about the aesthetic and the beauty of the thing that we were trying to create. It would probably be transformative at the same time, but really, we were trying to make something fabulous.

Sometimes it seemed like beauty was secondary to impact. There was a sort of iconoclastic challenge in an idea like turning a hundred thousand popsicle sticks into a hat.

Yes, but the most important thing was that it was beautiful, not the fact it was made from a hundred thousand popsicle sticks. It had to be exquisitely proportioned, beautifully made. Once we made a little boater out of matches because I had loved the idea of sailors building Notre Dame out of matches. Everything had a story, and what was unusual about John wasn’t just that the things that we were doing had a grandeur and a seasonality, but always that they had some sort of charm to them, too, which was particularly British. A French person or an Italian person couldn’t have done that. That was what attracted me to working with John because I knew his clothes had that charming element to them. Yes, he could do all sorts of different things, but what brought his clothes together, especially at Dior, which was 14 years of so many different styles, was a charm, a humour, a lightness.

The ingenuity of it, there was almost a make-do-and-mend element to it. Let’s take everything that we have at our fingertips and turn it into something amazing. Even the ‘Matrix’ collection in 1999, those hats with the furs. I mean, have you ever seen anything like that in your life?

No, and you won’t ever see anything like that again. I knew when we were talking about hunting, they were going to go with hunting clothes. So, we said should we have different animals on the head, different furs. Even then, I said we should be respectful of the animals. In our minds, it was more respectful to show what the animal actually looked like. So, I went to the best taxidermist in France, on a farm about an hour and a half’s drive outside Paris. We talked about the different poses and really spent a lot of time. I went out there every day for about three weeks and they were great. We got flak in the UK, people yelling, ‘monster’. The thing is if you are a hat-maker you have to use animal products. In the 1980s, the law governing feathers came in and I have only been able to use what we term ‘barnyard fowl’, chickens, geese, ducks, pheasants.41 We can use ostriches as well, because they are farmed, even though they are not indigenous to the UK. We can’t use peacock feathers any more. And you can’t use bird of paradise, or anything like that.

Those incredible plumes you did would be impossible now. What were they?

It was peacock for Dior. Albino peacock. There aren’t many of those in the world! Also, the big feather headdresses I did for Marc [Jacobs] at Vuitton, they were peacock.

I imagine it makes your job more interesting that you now need to realize the most extreme fantasies in a more prosaic way.

It is always changing every season. We can get this, we can’t get that. This is outlawed, that is impossible. Also, at the same time, we couldn’t use furs. I had so many suppliers who existed in the late 1970s and had been around since the war; they all closed down. There were three major flower suppliers in Soho, when I was first starting, with rooms and rooms of fabric flowers. You want anemones? Yes, we have them in 25 colours. All those people have gone. They can all be made in the Far East for much cheaper. The centre of the hat business when I first started was Luton; there were 80 factories doing a huge turnover. Now there are about six or seven.

‘Jean Paul Gaultier asked me to model in his first men’s fashion show. But I fell off my brother-in-law’s motorbike and couldn’t make it.’

Does that mean that in 10 years there will be none?

No, this is the weird thing about the hat business. Hats used to be a department-store purchase. Harrods at one end of the scale, Dickins and Jones or Debenhams at the other, they would have a hat department. Most of those hats were made in the UK, some might have been imported from Italy. A lot of the straws were imported from China anyway and had been for hundreds of years. But when hat-wearing declined, at the same time there were a lot of casual hats coming in: bobble hats, beanies made in Korea or China. And then formal hats started to be made over there as well, because that’s where the materials were coming from in the first place so it was just much cheaper. So in 10 years’ time, I think that hats will still be made abroad and there will still be a few dealers here to work with them and you will be able to buy hats everywhere. Actually, today in every shop you go into, you can buy a hat. In every fashion shop, there’ll be one or two, a beanie or a simple straw hat. It might be more for window dressing than it is for actual dressing; though if you take the new Dior shop, which just opened on the Champs-Élysées, it sold 151 hats last Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

I hope you’re on a royalty. Good lord, you’ve been designing hats for Dior for almost 25 years. Could you even choose a favourite show? I thought the Dior couture show for Spring 1998 at the Opéra Garnier was stupendous.

It was amazing. But at the same time, trying to get all that stuff ready every season was a jump into the dark, into oblivion. ‘Am I going to be able to do it or not?’ It was terrifying. For the Opéra Garnier, it was gorgeous when you saw everything coming down, but I remember we did a green and white mask made of papier-mâché, which hadn’t dried yet. So it kept bending, and the whole thing was about to fall apart. And there was another girl in a huge boater, and I pinned the hat to her wig, but the wig wasn’t pinned to her head and when she turned round, her wig moved over her face and the hat fell off.

How many hats would you have made for something like that?

Now Maria Grazia might show 80 outfits, each with a headpiece, but in those days there was no way we could made more than 25 or 30 because each outfit was so complicated. I think in that show, almost every person had something on their head. Normally when we would be having a design meeting, it was always like, ‘What has she got on her head?’ The hat reinforced the story. If she was wearing a dress like that, why would not she want to wear something on her head? But maybe she’s actually ripped it off and then put it on the side of the stage.

And you’d still have to make it? The completeness of the vision, who was that?

That was all John. The one other person who has that kind of understanding and who takes it that far is Marc Jacobs. I remember the first season I worked on his own label and not on Vuitton, he said, ‘It’s two women walking down the street.’ I asked, ‘Where are they?’ He said, ‘Rome, they’re shopping, but they’re not sure where yet.’ I said, ‘I think they are probably going to buy gloves. Are they going to match their gloves to the outfits?’ And he said, ‘Don’t be silly, they’re just buying gloves.’

He had a whole movie playing in his head.

Yes. It was a movie that he knew, but somehow we were inventing a new movie together. And this is interesting. People so often have a story behind the collection, as an influence, but actually the

important story is the one you are creating. Even though I am someone who will research things to the nth degree, it is actually what you make of it that is the exciting part. It’s not where the collection’s come from, it’s where it’s going.

Do you want to talk about the end of the Galliano era?

People would say designers were overworked or whatever, but what they didn’t realize is that we were actually running two houses. We were doing all of Dior – four prêt-à-porters every year, two haute coutures and furs and this and that and the other, the publicity and fragrances and all of that – and Galliano, which was four women’s collections, two men’s and a licensed collection. The speed at which you had to work and make decisions was crazy. You didn’t agonize over the length of a beige skirt, you did it and got on with it because you had to. That, in a curious way, was why things looked fresh, because they weren’t overworked. But it was a crazy pace to maintain. And after Steven passed away, it became even more impossible, in the same way that it had killed Christian Dior himself after 10 years and Yves Saint Laurent had a nervous breakdown; John suffered a similar fate eventually. And of course Bill [Gaytten] was there and he was a fantastic number two and held it all together when everybody thought it was going to fall apart. But Monsieur Arnault wanted someone who had a strong and clear vision of the future. I knew Raf because I had worked with him at Jil Sander, and when he came to Dior I was the only person he knew in the building. But he did the very opposite of John and it was correct that he did, though he still used extraordinary techniques. Even though he had loved hats at his own label and at Jil Sander, obviously hats at Dior were more complicated because John had shown so many of them. So Raf did hats sometimes. I did a bow thing that went round the neck, it was like a collar that had been in the hair but it kept falling down in the fitting room so I suggested we tie it round the neck, and those were the first three looks for Raf’s first prêt-à-porter. Even though I make hats, I have worked on clothes, too. I worked on many clothes for John. I did all the armour when he did the show on armour, and I did the collar things for Claude Montana, and many, many years ago, I worked on the mini-crini with Vivienne Westwood. Sometimes I slip from the head to further down the body. I worked on constructed things like that with Raf. And then when Maria Grazia arrived, she wanted to try the hats on herself as well as a fit model. She was not so much of a hat wearer, but her daughter Rachele was, so she started to make hats and there was a season when she put all my sketches of the hats in the programme. That was the first time I’d actually had acknowledgement within Dior of what I was doing, after having been there for 19 years.

John had never thought to include you as one of the contributors?

No, Steven would never have allowed it. But Maria Grazia was very much into it. She told them, ‘You have to do little films of Stephen Jones and put them on social media and Instagram and so on.’ I have worked with so many different designers over the years and I have actually had contracts with only two brands: Dior and Marc Jacobs. All the others have been season by season.

How, in an industry which is notoriously ungenerous and short of memory, have you managed to work with so many different and difficult people over extended periods of time, quite often simultaneously?

Hats are a product of conversations, and you have different conversations with different characters; that is how you develop your relationship with them, and what pops out at the end of that relationship is a hat. And yes, you have to be a diplomat. Sometimes you have to trust them, even though you may not like, know or understand what they are doing. If you don’t like what they are doing, it is maybe because of your preconceived ideas of what is beautiful or ugly and maybe your ideas need to be shaken up a bit. I think that would be very unsettling to a lot of people, but I am quite grounded in the way that I can leave all of that behind, I can get on the Eurostar, come back to England and be myself. The fact that maybe I always feel like an outsider is actually a huge benefit, because I can be an insider and an outsider at the same time. That gives me the ability to step away from it. I don’t just work with one person. I know if I stop working at Marc’s, a week later I’ll have someone else. So, my happiness, my reward, my being is not coming from one single person. That is very, very important.

Do you think you thrive on being unsettled though?

Yeah, I quite like being unsettled. I like being surprised. I don’t want to feel the same way all the time. I want fashion to inspire me.

What difference has social media made for you?

A great difference, because for us it was always about whether you got a hat in Elle or not, and whether people were going to know from that what it was that we did here. And the magazine would sell a million copies or whatever, so it was great to spread the message in that way. But now we can reach so many people in another way. Before, the press was the judge and the jury, because hats were about image as much as the object itself. But the great thing now is that it’s just more direct. It’s the client who is judge and jury.

When you talk about burnout for designers like Galliano, McQueen or Montana, I think people would look at your workload – all your own collections, the ones you do for other people, the endless travel – and they might fear the same fate for you. What immunizes you to the pressures that seemed so destructive to them? You said, ‘It’s not about me, it’s them.’ But you’re still putting in the hours. How do you sustain that? Plus your relationship with Craig?

When I work with designers, I will see them suffering. However, my workload is much greater than theirs. They have no concept.

But presumably they are aware that you are also working for Rei Kawakubo or Walter Van Beirendonck or whoever at the same time.

I’m not sure that they are particularly aware, really, because their world is all about them.

And your faith in human nature is unshaken by your constant exposure to all this self-centeredness and rampant ego?

Don’t forget talent! The universe hates an imbalance, so the more extraordinary the talent, the more extreme its counterbalance. To experience one extreme, you have to unfortunately experience the other. That is the way the dice are set. No pearl without a piece of grit. And, as I said, it’s because I could walk away. I think it is because I am interested in them. You know it is quite fascinating to try and find out what makes Marc Jacobs or Rei Kawakubo tick. Because I am independent, I have always been fascinated by being part of something as well. You know, I’m apart but it is quite nice to dip in and be part of something.

You have talked about the enormous ego required to run a fashion house, but you still seem to be naturally collaborative. You also said you have no ambition. Would you say that if there is no ambition then there can be no ego?

I remember long ago, there had been some in-fighting in the Galliano studio and Steven Robinson gathered everyone around and said, ‘Look, behave yourselves, look at Stephen Jones. When he comes here, he works with us and has no ego, he has no point to prove.’ And I said, ‘I’m sorry, Steven, but you are wrong.’ He said, ‘Why? That is how you are.’ And I said, ‘I have an ego so big that I have to have my own company in London, so I can escape all this and be somewhere that I make the decisions.’

‘You can put on Kim Kardashian face-sculpting make-up for a transformative effect – or you could just put on a hat. It’s so quick and immediate.’

Still, in a collaborative environment, you are not the queen bee fighting for your place in the sun.

I am fascinated by what makes those people tick. I know what I like, but it is great to have that challenged in a different flavour.

In a way, it is almost like you are an actor then. You can do all of that because you become a different person.

Yes. It is all an act, because it is all a lie. Fashion is a fabulous lie.

And a hat is absolutely anything you put on your head. There is something so basic about that.

I shall never forget that was what drove Raf and me apart, because I was going to do the hats and I said, ‘Yes, I can do that,’ and he said, ‘But I don’t want it to be false,’ and I said, ‘But it’s fashion. All fashion is this fabulous lie, it’s about not telling the truth.’ And I lost him at that point.

Forever?

Yeah, I think so. RuPaul said we’re all born naked and the rest is drag. Though I think Quentin Crisp said that first.

Didn’t John Galliano also say that a hat is an alibi? I think that’s the best line.

A hat is an alibi. A hat really is magical and has more effect on the wearer than anything else you can possibly wear because it is so completely transformative. It is this wonderful costume we make up and put on. The reason it is so charming is that you can take it off and put it back on. And you can’t do that with clothing because it takes effort. There are sleeves. And it has to fit.

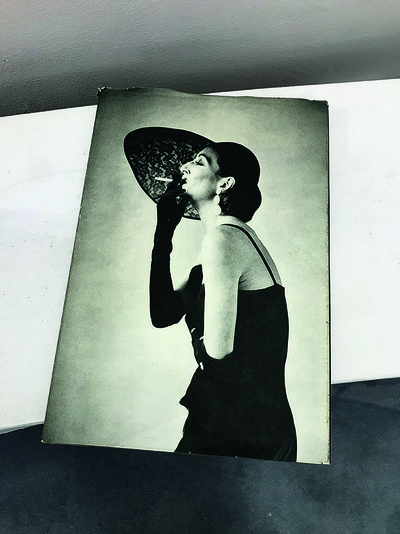

I read somewhere that the Queen’s clothing is almost like stripper’s clothing because it has to break away so she can get in and out of things really quickly. But I wanted to pitch another Stephen Jones quote at you. You said photography makes hats believable. That’s kind of an extension of the idea of designing hats for museum shows. More important than you designing the hat is someone taking a photo of someone wearing that hat.

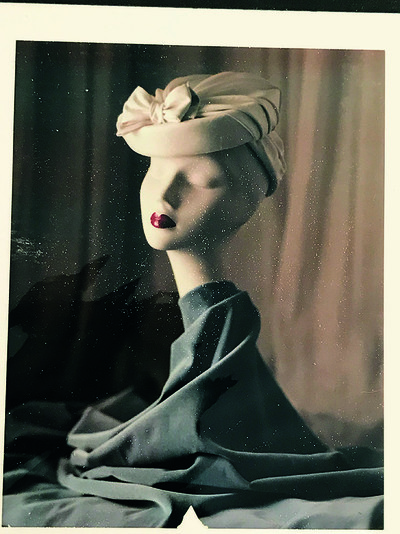

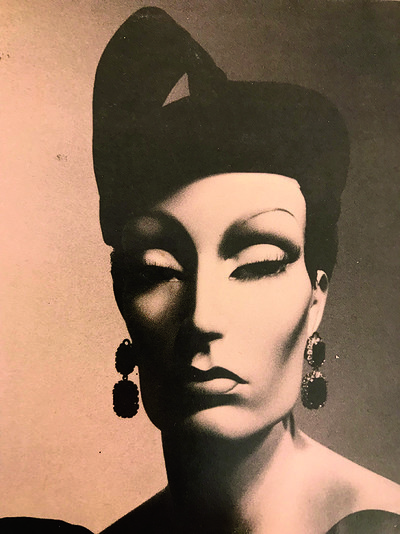

Next year I am curating an exhibition in Granville about Christian Dior hats, and what is so fascinating is seeing the passage of the hat from Monsieur Dior to Marc Bohan and beyond. In the time of Monsieur Dior, the hat was a continuation of the silhouette. It was just another item of clothing, like putting on a blouse to go with a skirt, or a belt to go with a coat. At the time of the New Look in 1947, Monsieur Dior knew he was making this pretty historic statement and the hat was part of a complete look, a part of reality. Saint Laurent, on the other hand, introduced hats as a fantasy, which is why he did masks and toques, and things that were fashionable in a particular moment. So it is interesting with Marc Bohan coming through in the 1960s because we had moved away from wearing hats by then, but the hat had become a great graphic tool, to add shadow on the face, for example. The hat functioned in an image just like when you go to a sideshow at a fair, you’re not going to get shoes to put on but there’s a hat which will make you look like a policeman or a nurse. The hat became an immediate and understandable costume, to anyone anywhere in the world.

Are you saying that the hat doesn’t exist as a reality? Surely, you’ve restored the realness.

That’s absolutely where my hats originally came from. They were made for people to look good in when they were out dancing in nightclubs. They weren’t about posing on a catwalk. Then I started doing hats for fashion shows and that was very different. But I think the wonderful thing about a hat is that it always makes a disassociation from reality – the reality of how we actually look. You could put Kim Kardashian face-sculpting make-up on for a transformative effect – or you could just put on a hat. It’s so quick and immediate and confrontational.

Do you think there is a new hat consciousness?

I think there is a hat consciousness which morphs all the time between countries, between the ages of people wearing them. I think people wear hats now because they perceive it to be a fashion item in the way that 15 years ago, they saw handbags as being the fashion items. Hats are an extension of that experience.

Do you know that for a fact, from your business?

I think certainly the big labels I work with, they know that. I think also with a hat there is an originality that handbags don’t have. An independence, an originality, and some fun. So hats are my alibi.

It suggests you are getting away with something.

Not being me, being that other person. I can be transformed by putting this thing on my head. And that is its magic.

I mentioned Rei Kawakubo and Walter Van Beirendonck. They work in such a different world from those other designers we’ve been talking about that it’s hard to imagine you’re dealing with the same situation.

I work with Rei in many ways, often not for runway shows. There’s fragrance, and Dover Street Market and different projects for the brand Comme des Garçons. Rei gives you carte blanche until she doesn’t like what you’ve done. So the thing you have to do is, don’t do something she is going to expect, don’t do the thing you think she is going to like, because automatically she will not like it. If I do work with her on a collection, what she wants is the salt in the sweet or the sweetness in the salt. She just wants the opposite, or the thing you didn’t dream of.

What always strikes me is the comparative restraint of the work you do with her. It’s a real embodiment of the concept behind your exhibition Stephen Jones & The Accent of Fashion.

I once asked Adrian [Joffe], ‘Why does she come to me to make hats?’ and he said, ‘Because she wanted an English gentleman to make some hats with her.’ Working with Walter is completely different. He wants you to follow his lead and is very unsettled if something different from what he expects is thrown into the pot. But that is what I do – I try and make him feel uncomfortable.

I think your hats for him are some of the greatest things you have ever made.

I love those hats, but it is somehow about the clash as well. Maybe that is also what it is about Rei. It is a different conversation with everybody.

So, you thrive on the compatibility and the conflict?

The conflict is the compatibility, and the compatibility is the conflict. And I sort of know where I stand because I am very much aware that I am part of them. But why do they want to be part of me? It is a very interesting cross-flow. They could get hats from anybody…

Someone – maybe it was you – once said that if every other country has a national dress that they trot out for special occasions, then England’s is the hat.

Totally. If people think of a British person, they probably think of the Queen. During the day, she is wearing a bright yellow or pink hat, and for ceremonial events, she is wearing a crown. The royal hat. The cartoon Englishman wears a bowler or a flat cap, or maybe a busby.

The hat is the national signifier.

Yes. But what is so wonderful now for me about hat-making has been having a huge diversity –modern word – because it is great to make a formal hat or a baseball cap, a hat for a tall person, a small person, a romantic person. It’s that difference which is interesting. If I said, ‘Oh yeah, all hats have to be this colour or this shape this season’, how dull is that? I am not on a mission to change the world. I don’t think I am even on a mission to find the right hat for the right person. It is just that by wearing a hat, people are going to have a good time. No greater purpose than that. And I think that goes for fashion as well.

So, by those tokens – diversity, transformation, pleasure – there is nothing more contemporary than a hat.

Yes, because a hat can be anything. I understand that within the fashion world, there is a past, present and future, though with the Internet and social media it’s all the same thing, a big quagmire, depending on how you perceive it. But the great thing about hats is that there is no past, present and future. They are timeless. I mean, if you want to wear a 1940s hat or a futuristic hat or a gladiator helmet: will people say you are old-fashioned because of that? Are they having a humour bypass, or what?

Do you think that is your legacy then? That the world sees hats through the eyes of Stephen Jones.

I don’t know. What is my legacy? He came, he saw, he made a hat.