How some of the industry got into the industry.

How some of the industry got into the industry.

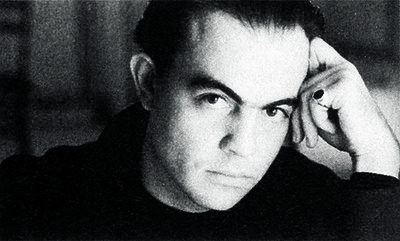

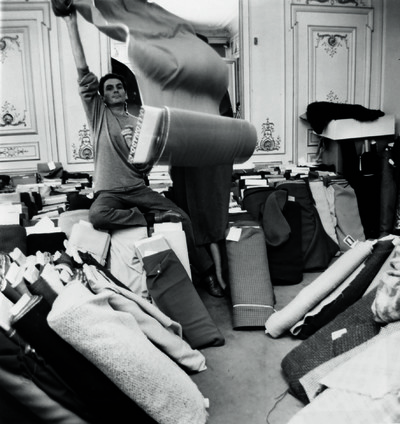

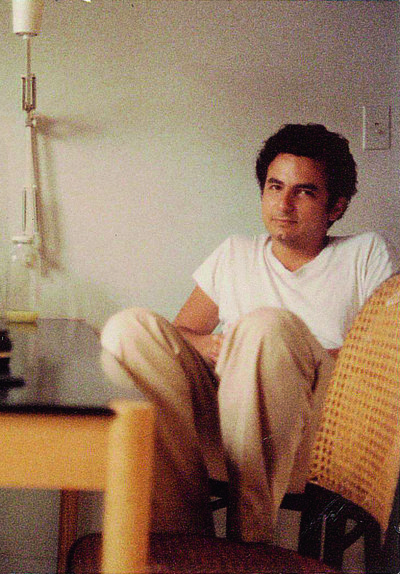

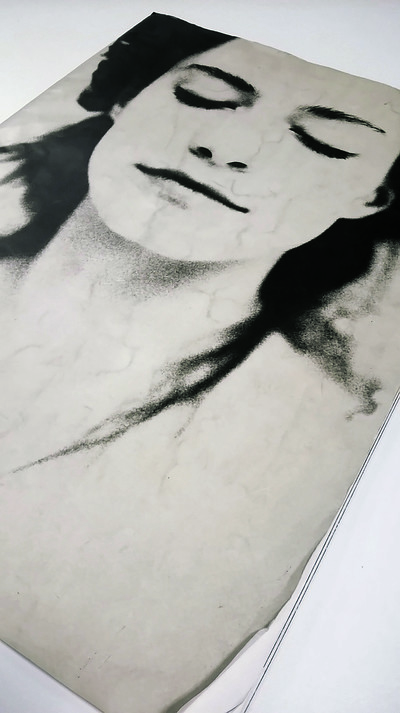

Amber Valletta aged 18, after her hair had been cut short by Yannick D’Is. Photo: James Breese.

Amber Valletta, model and actress

I wasn’t particularly into fashion growing up; I didn’t really know anything about it. I didn’t look at fashion magazines, and neither did my mom, but she enrolled me in a modelling school when I was 15 – one where you had to pay to take classes – because I wanted to act. After a couple of months, a scout came through and asked me if I would go to Europe for the summer. Of course I wanted to go: it was a big adventure! I did two weeks of test shots, and then I got my first job for Vogue Italia. I had no idea what I was supposed to be doing. I just knew how to goof around in front of a camera. I didn’t know then that I could make a professional career out of it. I was 15 years old, coming from Oklahoma. I was so green.

My big break came when I was 18 and I cut my hair short. I didn’t ask anyone around me; it was an instinctive thing. I went to the hairdresser Yannick D’Is, and he was, like, ‘You should do it.’ We didn’t do it right away, but when I bumped into him later at a fitting for Claude Montana, he said, ‘Now’s the time; let’s go do it!’ That moment was everything: they could finally see me as the girl I really was. I started being booked for shows: every magazine, every cover. And I met Kate Moss, when she’d just started modelling, and I met Shalom, too. Everybody joined the scene at the same time: it was a whole new era for fashion. All of these young people started to arrive: David Sims, Mario Sorrenti. A whole new generation of people: designers, stylists, photographers. Of course, there are other moments that stand out, like working with Steven Meisel, which I’m sure shifted my career in the beginning, or working with Peter Lindbergh or Craig McDean. Looking back on those moments, I think they added to the weight of my career, making it last for 30 years rather than two.

Christian Lacroix in 1986. Photo: Jean François Gaté.

Christian Lacroix, designer

After graduating from Montpellier University in 1973, I did a course in art history. My teachers advised me to join the École du Louvre in Paris and the Sorbonne, but the only possible path following that was to become a museum curator. In Paris, costume museums didn’t yet exist, and museums in general were classic, if not dusty. I felt trapped in a dead-end. As soon as I arrived in Paris, though, I met my wife Françoise, who encouraged me to showcase my sketches and have the courage to take my own path. I had it in mind to become a stage designer or even a fashion designer, since I was sketching opera productions and clothes that Françoise and I wanted to wear, but could never find in shops. A friend of ours, Nicole Bernardo, worked in fashion and introduced me to Marie Rucki, the head of Studio Berçot. I was too old to enrol – I was 25 – and her school was too expensive, so she kindly wrote letters to designers including Marc Bohan, then at Dior, Angelo Tarlazzi, and Karl Lagerfeld. As I already possessed a sense of fashion and colour, she also introduced me to Pierre Bergé, who owned Théâtre de l’Athénée. They all encouraged me. It might be impossible for young designers today to believe, but back then, it was easy to meet Karl Lagerfeld, who once spent an entire afternoon giving me advice. There were jobs everywhere, too: the stressful problem was which to choose. Jean-Jacques Picart offered my wife and I two positions: an internship at Hermés, which involved doing PR with him, and a design studio position with Nicole de Vesian, then in charge of styling with Catherine de Károlyi. Françoise chose to do PR with Mr Picart, and I chose the studio position, where I learned things I had never understood, such as how to build a collection.

Then, I received a phone call; a voice I didn’t recognize asking me to work with him, using tu and not vous. I didn’t dare ask his name, but nevertheless said, ‘Yes, of course.’ When I hung up, I didn’t know who had given me a job. But when I got home later that day, my wife said it was Guy Paulin, and I had agreed to join him as an assistant in charge of accessories in Italy. There I learned a lot about fashion and colours, before leaving for Japan, where I worked with Jun Ashida, advising his company on how to incorporate a ‘Parisian’ touch.

Step by step, from 1978 to 1980, I became a freelance designer, all while designing cheap shoes in Italy. Then, in 1981, the designer in charge of couture at Patou, where Karl Lagerfeld, Marc Bohan and Jean Paul Gaultier had started, became ill. The family and board asked Mr Picart for some names, and among a list of famous figures of the period, Mr Picart included mine. To showcase my work, Inès de la Fressange agreed to go into the couture house one morning with a little suitcase containing some Ashida numbers, Italian shoes, and jewels and accessories I had done for Guy Paulin. She staged a mini fashion show on her own, with the charm we all know, and I got an interview. I was unknown and inexpensive, and I got the job just two months before the January couture show.

In a hurry, I improvised a mess: a mix of 18th-century, Morocco, Cinderella, Death in Venice, Arles, and Toulouse-Lautrec. The most influential reviewer of the time wrote that the collection appeared to have been made by the courier and the telephone girl. The following season, I chose one line – black-and-red only – and we got our first good review. By the third collection, the applause at the end of the show was so great that the Patou family and chairman pushed me onto the runway in tears, carrying flowers. That led me to my first Golden Thimble in 1986 and, in 1987, my CFDA award for international designer of the year, just before I met Mr Arnault and built the House of Lacroix.

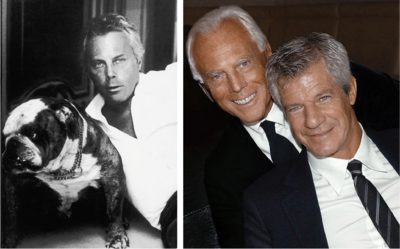

Giorgio Armani with his dog Gigi in 1979 (left) and with Leo Dell’Orco in 2000 (right).

Courtesy of Giorgio Armani.

Giorgio Armani, designer, chief executive and chairman, Giorgio Armani

I consider Leo Dell’Orco to be my right-hand man. I met him 45 years ago while strolling around Milan with my dog Gigi, who ran up to him wagging his tail, as though he knew him. That’s how he came into my life – so unexpectedly – and he has been by my side ever since. He is the person to whom I have entrusted my most private thoughts, and he keeps them to himself, always with great discretion. He has always been close to me, first during my business partner Sergio Galeotti’s illness and then over the years, working alongside me in formulating the stylistic direction of the men’s lines. What I appreciate most about his personality is his wonderful quality of being able to smile when you first meet him in the morning. And then his tenacity and enthusiasm, and, above all, his great heart of gold. I believe that his presence, sometimes discreet and sometimes lively, has helped to bring me out of my timid and reserved character.

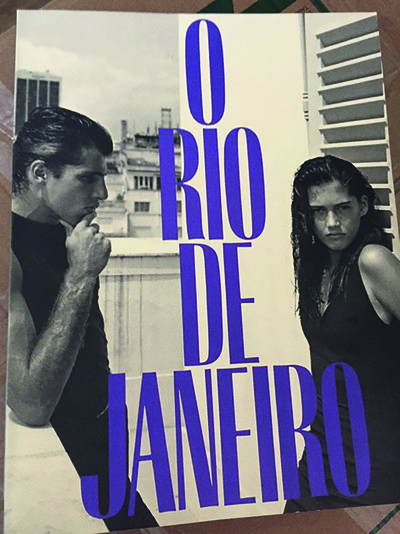

Bruce Weber, O Rio De Janeiro (1986).

Joe McKenna, stylist

I started out in 1985. I had never assisted. There were only a few stylists working then, and it was impossible to get a foot in the door at Vogue or Bazaar. I didn’t know how a fashion shoot worked; I could only imagine it. I did some tests, and I was lucky they ran in The Face and Tatler, but it was difficult to get work. There wasn’t the volume of work that there is today. One evening in November that year, my phone rang. The voice on the other end said: ‘Oh hi, is that Joe? This is Bruce Weber.’ I had never met Bruce or spoken to him, but I was a huge fan of his work. I had only ever dreamed of working with him. I actually thought it was a friend playing a prank. ‘Would you like to come to Rio and work on some pictures? Just bring a few swimsuits,’ he said. I was thrilled. Those pictures became the book O Rio de Janeiro, published in 1986. I owe my break to Bruce Weber.

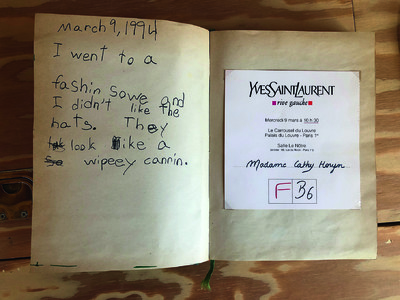

Pages from Cathy Horyn’s son’s scrapbook when he accompanied his mother to the Autumn/Winter 1994 show season in Paris.

Cathy Horyn, writer

I didn’t grow up with fashion, and I didn’t hanker to be a fashion journalist, but one day, when I was working at The Virginian Pilot newspaper, I was very pregnant and was sitting at the desk of the night-rewrite guy. He had a copy of Editor and Publisher magazine, which had all the job offers in it. There was an ad for The Detroit News for a fashion writer: no fashion experience necessary; must be a good writer. I answered the ad and they brought me in for an interview with a woman named Susan Wyland. She asked me to do a try-out: I basically had to conjure up two story ideas that were vaguely in the news, but showed my interpretation of fashion. They got published and that was the start of it.

Sure, there were days when I was out of my depth, when things weren’t going my way and I felt like I was in high school again. I mean, in the first year, I went to Milan and stayed in a hotel that was near the airport. I just didn’t know, and clearly the travel agent didn’t know either. I had to take a taxi and the bus in! But once I got over that first year of making dumb mistakes, the beat got more interesting and there were more layers to it, more to do. By the time I got to the Washington Post in 1990, I’d spent four years in Detroit. I felt that I had a voice, that I knew the kinds of stories I wanted to write, and that I knew how to be a critic.

I felt that way well into my time at the New York Times; I thought I knew a lot when I got there, but eventually realized I didn’t. At the Times, I spent more time going to couture, which I didn’t do when I was at the Washington Post. Understanding how the clothes are made, who the clients are, how that part of the business operates: it was a whole other world.

In terms of the people I’ve met along the way, I used to love chatting to the girls at the shows: I would sit and watch and be fascinated by them. I eventually came to know Marina Schiano, who just died. Candy Pratts Price, Phyllis Posnick: I learned a lot from them. They saw clothes in a way I didn’t.

If I had to single out one person, though, I’d have to say Bill Blass. We connected when I was in Detroit. He’d come up for the auto show as part of his relationship with Ford; it was strictly a branding thing. Later, when I got to Washington, I used to go to the 550 Building when I was in New York and stop on Bill’s floor, where he’d fill me in on everything. He made me feel like I was an insider, like I had graduated to another level of the business.

Chérie Moda, September 1971 issue.

Carla Sozzani, founder, 10 Corso Como

I was always wildly into fashion. When I was 16, I would buy Pucci like crazy, and my father would get very upset. At the same time, I remember him taking me to Paris in about 1966. We went to the Courrèges shop, and he bought me this incredible, bright-yellow vinyl tunic with matching pants. It remains an extremely vivid memory.

I always loved magazines, too. I was addicted to Alexey Brodovitch’s work at Bazaar, obsessed with the graphics and the photography, and the way the models moved. I was always cutting the pages out, reassembling them, wanting to make magazines myself, wanting to be part of that world.

By 1967, I was at university and living in London a lot of the time. I actually had my university card taken away from me because I was wearing a suit. They said a woman could not attend university wearing trousers, which was ironic, because ultimately what that time in London taught me was freedom. Everything had been so strict, and, in a matter of months, we went from absolute conservatism to total freedom: to dream, to think, to dress the way you wanted. That had a profound effect on me.

In 1968, there was the political revolution in Italy and it was impossible to study unless you were politically active, which I was not. I remember being on holiday with a friend in Sardinia in 1968, when my father sent me a telegram, saying, ‘You’re behaving like a spoiled child! Come back and study or go to work!’ So I came home and started work for a friend of my mother, who had a chain of specialist magazines: children, knitwear, haute couture, cuisine, brides, clothing patterns. My first job was at Chérie Moda magazine: a half day here and there, then full-time. And I started to go to Florence, to see collections at Palazzo Strozzi and Palazzo Pitti.

Then I would go to Rome for the haute couture. I met everyone from Valentino to Sorelle Fontana. And then ready-to-wear in Milan. Working at these magazines gave me a wide vision; beyond fashion, to culture, food, art, design, lifestyle. I met Anna Piaggi through her husband, the photographer Alfa Castaldi, and she introduced me to people like Manolo Blahnik and Walter Albini. I was still only 20, so Anna and Alfa were kind of my mentors.

All of the skills I was learning were part of one single thing: the editorial experience. I learned how to edit, so when I opened my gallery in 1989, and then 10 Corso Como in 1991, I was approaching them with an editorial eye. For me, it has always been about editing: editing photography, editing exhibitions, editing fashion, accessories, design. This is what I love and enjoy, and always will.

Pierre Cardin in his Paris atelier, 1960. Photo: Pierre Cardin Archives.

Pierre Cardin, designer and entrepreneur

I always wanted to be a couturier. In 1936, aged 14, I began my apprenticeship with a tailor in Vichy. After the war, I began working for Paquin in 1945, then for Schiaparelli, but it was meeting Jean Cocteau that allowed me to live my dream and begin working at Dior. As first tailor at the house, I was part of the success of the Bar suit, which defined the New Look. That gave me the desire and strength to strike out by myself and set up my own house.

I was ambitious; I had ideas; I wanted to succeed. I immediately put all of my ferocious energy into raising awareness of my name. From the beginning, I wanted to develop my designs and make them accessible to as many people as possible. That drove me to create a formal licensing system and to design ready-to-wear. My inexhaustible energy, my independence, and the facility with which I drew and designed also helped. My style, my appetite for experimentation, for inventive forms and new technologies, my unusual geometric shapes: all were immediately popular. I think my strength also came from my character.

The political and economic context of the time was undeniably simpler than it is now. What I accomplished then would simply no longer be possible today. Times have obviously changed, even if the globalized movement of goods and trade has been simplified. Bureaucratic difficulties and slowness remain a brake on more entrepreneurial spirits, though, which I am sorry about. I took revenge on life, and with the end of the war, the wind of freedom that blew across Paris gave me the wings to succeed.

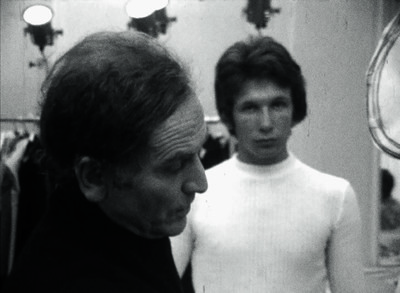

Jean Paul Gaultier at the time he was assisting Pierre Cardin, as seen in the documentary Personnage: l’empire Cardin by Adrian Maben (1970).

Collection Variances/INA.

Jean Paul Gaultier, designer

I got my big break with Pierre Cardin on the day of my 18th birthday. I had decided that I wanted to be a couturier after seeing Jacques Becker’s film Falbalas, about a tragic love affair in a Paris couture house in the 1940s. I was 11 or 12, and I started reading fashion magazines and drawing my own collections. I would see that a couturier had presented 300 outfits and I would draw 320 to outdo him. I would even write my own reviews. By the time I was 17 I had sent my sketches to every couture house in Paris. On my 18th birthday I came home from school and my mother told me that Monsieur Cardin had called, and that I should go to meet him that same afternoon. I was so scared, I asked her to go with me. I got the job, but as I was still at school I could only work a few days a week. When the couture show finished and the school holidays started, I went on holiday without asking for permission. I got a good scolding when I came back. Monsieur Cardin taught me that freedom is the most important thing. Freedom to live your life as you want and to create as you feel, regardless of conventions. I owe him everything.

Ed Filipowski with his then KCD boss Kezia Keeble in the offices of Keeble Cavaco & Duka Public Relations, New York City, 1988. Photo: Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images.

Ed Filipowski, co-chairman, KCD

I was not born into fashion; I aspired to fashion from a small town in Pittsburgh. I came to New York and I couldn’t quite find my way into the right doors, so I first worked at an ad agency and a non-fashion PR firm.

I got my first job by reading. I read about the hot advertising and PR firm Keeble Cavaco and Duka (KCD) and its president Kezia Keeble, who had come from Vogue. I read that Keeble was a super stylist who worked with Steven Meisel, Bruce Weber, and Richard Avedon. I read how she was one of the most beautiful women around, so striking in her Chanel suits, and how she was working with John Duka on the New York Times as well as Paul Cavaco, who was working with Bruce Weber. I also read that they landed the Charivari account, which was the hot store on 57th Street where I would go on my lunchbreak to spend money I didn’t have on Gaultier leather biker jackets to wear clubbing.

As a creative kid, I had the idea to send Kezia flowers in a Charivari bag. I went to Zezé, still one of New York’s top florists, bought some flowers I couldn’t afford, and sent them to Kezia with a note saying congratulations on landing Charivari, and if you are looking for somebody to work for you, I would love to talk to you. A day later, I got a phone call. This voice said: ‘I’m Kezia Keeble. I don’t know who you are, but you happen to have sent me my favourite flowers – freesias – and, I don’t know, but I just feel that I need to talk to you.’

She brought me in for an interview the next evening and I sat by her desk, scared witless. We talked for three hours. I remember that she caught on halfway through that I knew nothing about fashion, because at one point she looked at me and said, who is Polly Mellen? She was one of the top stylists at Vogue at that time, and I honestly didn’t know, so I said so. There was a dead silence for maybe about three minutes. She offered me a job that night, but later on she laughingly told me that she almost didn’t, because I didn’t know who Polly Mellen was. Miss Mellen always enjoyed that story later on. Kezia became my mentor, and I haven’t left KCD since.

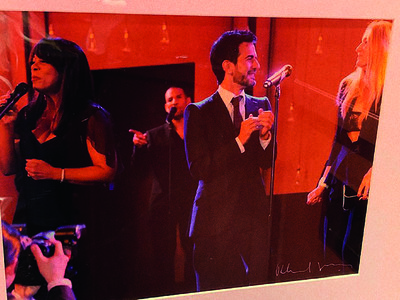

Julie de Libran (right) on stage with Marc Jacobs and Donna Summer, at the launch of the Louis Vuitton Bond Street maison store, 2010. Photo: Richard Young.

Julie de Libran, founder and creative director, Dress by Julie de Libran

It’s a hard one, as all of the experiences I’ve had working alongside different designers have contributed to how I create today. My first job was in the Milan studio of Gianfranco Ferré, where I observed every step of creating a collection. We had these closets filled with shapes of clothes: ‘volumes’, I guess you could say. I would drape and pin them on a fitting model in the atelier, and he would sketch from that. At Gianni Versace, I was lucky to be close to the ateliers, which were in the same building. I would spend hours on end there, developing my understanding of the construction of the clothes: pattern-making, draping, even assembling chainmail dresses with pliers.

And then the 10 and a half years – I insist on those last six months – I spent at Prada, from 1998. It felt very ‘fashion’, very contemporary. I learned so much about the business by working close to Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli, while being pushed to creative extremes in order to fulfil Miuccia’s vision. But it was during my time at Louis Vuitton, working with Marc Jacobs from 2008, when I really felt I was given my big break. Marc was so extremely generous, and really let me work in the first person. If I had to single out a particular moment, it would have to be in 2010 when the Louis Vuitton maison reopened on Bond Street in London. I was pulled on stage with Marc, alongside Donna Summer, who was wearing one of my dresses. I have no idea how it happened, but there I was, singing ‘On the Radio’ to a crowd that included Catherine Deneuve! I’m usually extremely shy, but after that, I knew that I’d come out of my shell. Singing on stage helped me realize that I can do things on my own – it prepared me to take centre stage in my career.

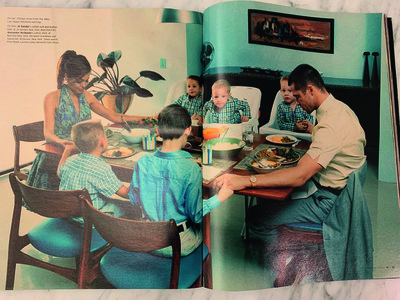

‘Domestic Bliss’, featuring Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, photographed by Steven Klein; W magazine, July 2005 issue.

Dennis Freedman, creative director

At W magazine, where I was creative director, our July issue was generally the only one in the year when we’d feature a guy on the cover, and for 2005, Brad Pitt was supposed to be that guy. He was arguably the world’s biggest male movie star, and, given the intense media speculation at the time surrounding his relationship with Angelina Jolie – despite still being married to Jennifer Aniston – he was magazine gold dust.

With this on my mind, I phoned Brad’s publicist, essentially to confirm what we already knew – that there’d be absolutely no way he’d agree to the cover request – so we could just move on. She graciously said that she’d talk to him anyway, and then called me back to say, ‘Dennis, I just spoke to Brad and he wants to do the cover. But on one condition: that it’s a photo essay in which he and Angelina Jolie play a married couple with five children.’ Having already worked with Brad in past, we had established not just a level of trust, but a level of confidence. He knew that if we were going to do this, it was going to be a major collaboration. On Brad’s suggestion, the shoot would be set in 1963, the era of the Kennedy assassination.

We had exactly one week to make it happen. I knew I wanted to work with Steven Klein, and that we’d be shooting in a house in Palm Springs. Steven and I created a precise storyboard, something we rarely ever do. It was fascinating to see just how invested Brad was in the imagery and the storyline: he was very serious about that moment in American history; in one of the images, they are watching coverage of the assassination on a vintage television.

America in the 1960s was a time when everything was changing. This was 1963, which was not far from the 1950s, and a simpler time for America, until the assassination happened. If you look at the pictures, they really address that shift towards violence: in one image, they’re the perfect family, saying grace at the dinner table; turn the page and there’s the picture of Brad holding a gun and then another with him grabbing Angelina by the throat. This was domestic violence in a 60-page portfolio entitled ‘Domestic Bliss’; it was a mirror held up to America. With its meaning further heightened by the rumours about Jennifer Aniston and Brad. None of which, of course, was discussed. To be frank, it is still unclear to me what Brad’s motivations were at the time.

Fortunately, at W, we’d established the credibility at that point to pull off something like this shoot. For me, it became a transformative moment, one that could only happen if you set the precedent, if the soil is fertile. Reflecting on those pictures today, the story certainly wasn’t my initial ‘big break’ into the industry; it wasn’t the moment we hit our stride at the magazine, either – we had already done that – but it was the kind of moment that becomes an extraordinary cultural signifier, one that goes right to the heart of society, beyond anyone’s expectations.

Gaia Repossi, creative director, Repossi

A vivid, lucid memory. My first big break. 2010. The Berbère Collection. A sudden reaction to an efficient design. Timeless. Correct. Charged with an ancestral language. It spoke. Simple design loud enough to scream. Every finger, every hand like a flowing river of gold. Energy unleashed. I was freed. The engine ready to start. The visuals of the campaign narrated a strong, almost albino creature staring from above. Nothing to prove. No more false messages. Just the first syllables of a new statement: Repossi born again.

‘An image that accompanied my exhibition at the Pineal Eye in London, when I graduated in 2001.’

Kim Jones, artistic director, Dior Men

I was very fortunate at the beginning of my career. I was working at Gimme Five in London and had already met several influential people, when I did an installation with my graduate collection at the Pineal Eye in Soho. Then I went to Japan for the first time, and when I arrived back, I found that John Galliano had purchased a part of my collection, which I guess was a big compliment. Shortly after that, Keith Warren, the head of Louis Vuitton menswear asked me to do some prints for a collection, and shortly after that I met Lee McQueen, who became a friend.

Karl Lagerfeld illustration, 1992.

Michel Gaubert, DJ and producer

September 1989: The scene is Champs Disques, a really good record store for which I was the buyer. Karl Lagerfeld was coming to visit almost every day to get his supply of new sounds. One afternoon his studio came over and told me, ‘Karl would like you to create the music for his upcoming show.’ The inspiration they gave me was the album Waltz Darling by Malcolm McLaren. I liked it. It somehow fitted the idea I had of Karl Lagerfeld’s musical mind. An hour later, I said yes. And then I wondered why I said yes. I started to doubt that I could do it. I knew I had the power to do it, but I did not have the technical knowledge to make it happen the way I wanted. Insecurity got the better of me. I doubted my capacity to be up to the expectations of someone like Karl Lagerfeld, and I did not want to disappoint the audience attending the show. I did so much research: of operas, operettas, waltzes. I was determined to find the right ingredients. Then I called Dimitri from Paris – who I had also met at Champs Disques – to help me match them onto Frankie Knuckles, De La Soul, and Soul II Soul. He jumped on board right away. The soundtrack turned out great and was quite impressive at the time. It was the beginning of a 30-year relationship with Karl, and we teamed up with Dimitri from Paris for a few years after that.

Insecurity is your worst enemy. Determination and will are key, and if you believe you can do it, you will make it happen. There’s no need to be afraid – just trust your instincts.

‘She was helping carrying the shoes too.’

Fabrizio Viti, shoe style director, Louis Vuitton

My career started last century, and I can think of a number of fundamental moments:

-

My encounter with a photocopier in my very first job as a studio-assistant-slash-housekeeper. I discovered that anything powered by elettricità is not for me.

-

My first day in a shoe factory in the middle of nowhere, as the assistant to Patrick Cox. I felt that it would be not the last time.

-

The last Louis Vuitton Cruise show in New York. It’s all worth it when you are part of something like that.

-

The first time I presented my own brand of shoes to the world, there was a strike in Paris and we had to carry boxes and boxes of shoes by hand in the rain. My advice is to stay grounded.

Jean Touitou, New York City, early 1980s.

Jean Touitou, founder, A.P.C.

I never thought about fashion to begin with; it wasn’t a goal. Fashion wasn’t even attractive to me – a beautiful silhouette was. Also, I wanted to be around hard-working and fun creative individuals. While I wasn’t really watching ‘fashion’, I could see that some designers had a vision, and I could figure out that some would endure and that some would be forgotten. I was more interested in factories, retailers, printers, fabric and yarn suppliers, and tanneries, than in the people in the fashion spotlight. So I took a job at Kenzo as a warehouse worker. I used to wash classic English men’s suiting cloth in my bathtub, so that it would lose its corporate spirit, and presented collections in my apartment. After some years, I made collections that finally got some attention, but what I wanted to do wasn’t commercial enough for me to rely on. As a ghost designer and producer, brands from the fashion industry financed me, so that I could do what I wanted. I would make money designing and producing ‘sexy’ stuff for other brands, so that I could finance my unsexy looks – which were the sexiest to me.

An image from the series entitled Ceremony, 2006.

Alasdair McLellan, photographer

My first big break was in 2002 when Julie Brown from MAP Agency took an interest in my work and asked if she could represent me. Obviously, I said yes. Julie’s got an amazing eye, and she was very warm, so I was very attracted to working with her. She then introduced me to Joe McKenna, with whom I worked on a shoot in my hometown, Doncaster. He’s a stylist who everyone adores and respects, so working with him meant a lot – people take notice of who he’s working with. It was awhile before Julie took me on fully because she felt that I wasn’t quite ready. I’d go in to see her, go off to do more work, then go back to see her again. It’s true that you continue to get big breaks as you go on, like the Miu Miu campaign and Michael and Mathias from M/M Paris doing the art direction of all my books. I never assisted anyone, so it took me a bit longer to crack the industry. You do see other people who are assisting get breaks, because they are getting to meet magazine editors, hair and make-up people, and a lot of other creative people on set. Within my first week of moving to London, I also met editor and journalist Jo-Ann Furniss, and we’ve been good friends ever since. I was taking my folio around various magazines and she happened to see my work when she was interning. She said how much she liked it, and we just got on. We have a similar point of view on things, and while our meeting might not be considered a ‘big break’, meeting her meant a lot; we formed a special relationship and have since gone on to do really amazing and big projects together. People can often be very critical of fashion photography, but what I have always liked about fashion is how you can really create any world you wish from scratch, and you get a platform, like a magazine, to put it in. I like the fact that you can almost do anything you want to as long as you’ve got clothing in the picture. It has a point to it, but you also have complete freedom.

Alexa Chung on the set of Popworld, 2006.

Alexa Chung, model and designer

When I was 22, I was made co-host of a television show on Channel 4 in the UK called Popworld. It was irreverent, anarchic and fun. We interviewed musicians from around the world with the kind of sardonic disdain that only a very young, inexperienced Brit could muster. This was 2007, so the bands coming through were Red Hot Chili Peppers, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Gwen Stefani and her Harajuku girls, or Beth Ditto and the Gossip. Once Popworld aired, people became increasingly interested in what I was wearing each week, which was usually a mixture of vintage, Topshop and Balenciaga jeans, and eventually that eclipsed what I was saying.

I miss that TV show, it was a riot.

Sasha P for i-D, 2006, photographed by Daniel Jackson.

Alastair McKimm, editor in chief, i-D

A lot led up to this moment, but the series I styled for i-D in 2006 with photographer Daniel Jackson felt like a real turning point. I had styled a few small pieces, pages and spreads before, but this was my first main fashion story for the magazine. It was long before I had edit approval or even saw any kind of layout, so I only saw the story when it was on a newsstand in Carnaby Street in early September. For the first time, I felt I might have a future in this.

The Missoni family on the runway post-show, 1990. Photo: Michael Heeg.

Margherita Missoni, creative director, M Missoni

My first break into fashion must have been when I was five or six years old. My grandparents would still go out on to the catwalk at the end of a show, and my cousins, my siblings and I would be sitting on the floor of the front row among the crowd. That year, as soon as they walked out, one of us started running and went up on to the catwalk, so we all followed and we walked the whole catwalk with the models. We did that for the following few years.

The first YOOX landing page, 2000.

Federico Marchetti, chairman and CEO, YOOX Net-a-Porter Group

I came up with the idea for YOOX in late 1999, quit my job and quickly built a business plan. It was a race against time, though nobody knew then just how true that was. Back then, venture capital was non-existent in Italy. I cold-called one of Milan’s few tech investors and made my pitch. He liked it immediately and invested €1.5 million up front, promising another €6 million if we had the website up and running in three months. We worked around the clock to get YOOX off the ground. And we stayed focused even as the dotcom bubble crashed down around us and Europe began to adjust to a new single currency. I’ll never forget the moment the homepage went live. We did a countdown and ended up having to repeat the last minute: ‘5, 4, 3, 2, 1… 59, 58…’ But then we were live. We made our first sale in the first second, to a woman in the Netherlands who bought a Versace dress for 88,000 Italian lira. That was our big break. One hundred more purchases followed in the first few days. An entrepreneur never really knows how good an idea is until customers buy into it.

Michael Kors, as photographed for his debut Vogue feature, 1981.

Courtesy of Michael Kors; photo: Christophe von Hohenberg.

Michael Kors, founder and creative director, Michael Kors

While I was studying at FIT, I needed a job and I knew I wanted to work in retail. One day, I went into Lothar’s, a boutique on 57th Street across the street from Bergdorf Goodman that specialized in French sportswear and sold the most expensive tie-dye jeans you could buy. I’m in there mooning over all the clothes and someone says to me, ‘You know, we’re hiring people to work in the store part-time.’ I took the job, of course, and it was the most amazing learning experience because I got to see how people shopped. People would come in and buy the same pair of jeans in 10 colours. I sold jeans to Jackie Kennedy, to Goldie Hawn, to Rudolf Nureyev. It was at Lothar’s that I realized that people who can have anything want it all. They want to be glamorous but feel comfortable at the same time. Even the most indulgent person can be practical. A few months later, they asked me what I thought was missing in the store, and before I knew it, I was designing a soup-to-nuts collection. I was given carte-blanche at 19 years old. I designed based on my mood and the customers: one week it was a trench coat, the next it was an evening gown, and the week after that it was a T-shirt and bathing suit. It was my entrée into thinking about a wardrobe.

One day, Dawn Mello goes walking by while I’m dressing the windows. She comes inside and says, ‘Excuse me, these are not the same clothes that Lothar’s has always carried. Do you know anything about the clothes?’ She thought I was just the display guy. I said, ‘Well, I designed them.’ And she said, ‘Well, if you ever decide to go into business on your own, give me a call.’ I went home that night and started sketching my first collection.

I set up a meeting with Dawn and the people at Bergdorf’s and very quickly whipped together a collection. We made the samples with rented sewing machines in my apartment on 23rd Street. Everything came in two sizes: P or S. I went back to Bergdorf’s and said, ‘I want to do a trunk show.’ I wasn’t even entirely sure what a trunk show was, but I knew that Bill Blass and Oscar de la Renta did them. Bergdorf’s agreed, and I called all the women I knew from Lothar’s. They came and I sold most of what we had there that day. I’ve been in Bergdorf’s ever since.

‘I had just moved back to New York City with the Financial Times, in 2008, after 12 years in London. I left a non-fashion person, and came back a fashion person, and this picture sort of represents that to me.’

Vanessa Friedman, fashion director and chief fashion critic, New York Times

‘Break’ is a funny word for me to think about, because I would never have considered the fulcrum on which my career turned, or the door I walked through to be a break at the time. It was kind of an accident, a happenstance. If we’re talking about what one would think of as a classic break, I would say it was when I became fashion editor at the Financial Times. It was the first time I had ever done an all-fashion job. That was in 2003, but in 1997 or 1998, not long after I arrived in the UK as a freelancer, I sent a cold pitch to Lucia van der Post, who was an editor at the FT. I don’t even remember the story I was pitching; it was probably culture-related because that’s largely what I was writing about at the time. She looked at my resumé, assumed that I was a fashion writer because I had worked at Vogue in the US, and assigned me a story on boots. At that point, if someone had assigned me a story on tyre treads, I would have done it if they had paid me. I became her freelance fashion contributor, and at one point I had a contract to write about fashion for the FT for about a year. Later, after leaving the FT, joining InStyle as features editor, and having two children, I ended up back at the FT as its fashion editor. At the time, I was pretty sure that I had entered the world of fashion. But I found becoming a full-time fashion person to be a complicated mental evolution. I had grown up in a world where fashion was not considered a particularly serious subject, or something that serious people would study or do. I once told a banker at Rothschild’s that I was fashion editor at the FT, and he laughed so hard I thought he was going to have a heart attack, like, ‘They have a fashion editor!’ It’s not a reaction guaranteed to fill you with joy. They had actually only just created the role, so when I decided to go back and apply for the job, it just seemed like a really interesting challenge: trying to understand what fashion means in a place that is not a fashion-focused outlet, that was for a cultured, well-travelled, educated readership that thought about lots of other things and had to get dressed. I felt that that reflected my own relationship to fashion, to the role it played in my own life. It made me realize that fashion is an incredibly important and rich subject that everyone in the world thinks about whether they want to admit it or not: everyone gets dressed and makes choices about what to put on their body. It is a huge part of human communication. All the things I was interested in – identity politics, sociology, philosophy – are contained in fashion. It is a fantastic subject, but those starting out should learn about everything else before they learn about fashion, because it is all part of the same thing. All of these subjects are connected.

Ivan Bart, president, IMG Models

I thought I was going to have a career in healthcare. I majored in psychology, but took time off after college to travel to Europe. I was a kid from Brooklyn and hadn’t really travelled; visiting other countries, cultures and languages, I realized what had been missing in my life. I grew my hair very long, and there I was, travelling around Europe, digging my long hair, talking to some women in Greece, and they asked me what I would do when I returned to America. My answer: I just want to travel around the world and have long hair. After I got back to New York, I decided to get my masters in psychology. I began work for a therapist, but because this therapist was sort of famous, I basically worked in a PR capacity, booking them to speak at engagements. That led to my first PR gig at Grosik and Partners, which had a modelling agency attached to it.

I’m a night owl, so I was up late when I saw a commercial for the Ritz Thrift Shop, a vintage clothing store on 57th Street in Manhattan. This was 1986, and the commercial was probably filmed in 1968, yet they were still running it: a woman getting out of a cab. I called up the shop and said, ‘Listen, my firm could really help you.’ I must have been about 21. He was really offended and hung up the phone, but I kept calling until finally I got a meeting. He came to the agency. I was so junior, I didn’t even think I would be invited into the meeting, and I was sitting at my desk when I got a tap on the shoulder and heard: ‘The gentleman will not have this meeting without you.’ I walked in, and he said, ‘I’m here because Ivan called me, and told me you guys can help, so explain to me how that is going to happen.’ I did most of the talking, explaining why I thought their commercial wasn’t reflective of the modern woman and the guy hired us. My boss was so impressed, he said: ‘I want to give you a raise and a promotion. What do you want to do?’ And, pointing towards the modelling agency, I said, ‘I want to work there.’

So, I did. My career gradually built as I changed firms, and about three or four years later, on the plane journey home from Milan, I suddenly realized that I had accomplished exactly what I had set out to do: to have long hair and travel the world! And that inspired me to cut my hair off.

Studying psychology was totally applicable to managing talent, because a talent manager manages people. Good people skills are one thing, but reading Carl Jung and Freud helps with understanding human behaviour and people’s motivations. When I’m talking with a talent, I am also coaching them on how people might react to things, what they need to communicate, and what they can expect, be it from a photography shoot or just a meeting. I have met some fantastic mentors and people along the way whom I have always acknowledged: Mark Grosik, Eileen Ford, Mark McCormack from IMG, Ted Forstmann, Mark Shapiro, Ari Emanuel, and Patrick Whitesell. Through my career, I have become more educated in the business of fashion, design, designers, editors, and everything else that goes into the business I love.

I think you just have to have an intention, like having long hair and wanting to travel around the world. You don’t have to know what you want to do, you just have to have an intention.

Victoire de Castellane in the Chanel offices, Paris, 1987.

Victoire de Castellane, creative director, Dior Joaillerie

I always really enjoyed fashion, and loved creating looks for myself, but I was never really looking to work in the industry. At the time, fashion in my mind was a free environment populated by people who took themselves very seriously, some of whom were incredibly talented. I ended up working in fashion totally by coincidence.

My professional life has been interspersed with important encounters, but the one that led me into fashion came at Chanel, when I went there to lend a friend of mine a hand with sending invitations for a couture show. Karl knew me through my uncle Gilles Dufour, who was his assistant at the time, and suggested that I stay. Back then, the success of a house came from its creative freedom, and the sentiment invested in the work. Everything was there for the making. Everything was

possible.

Flyer for IDEA Books’ first pop-up store, 2009.

David Owen, co-founder, IDEA Books

In 2009, I was making a comedy series in London for American cable television. I won’t even say what the series was called: it’s not famous, or known, or even any good. My partner, Angela, walked past the St Martins Lane Hotel and saw its shop space, which had originally been designed by Philippe Starck but was being used as a room to store luggage. She asked if she could have it as a pop-up shop. At that point we sold some vintage books through Dover Street Market under the name of Angela Hill. The hotel said yes and gave Angela the space for three months: the whole summer! So we went for it. I quit the TV company and called Vitsoe about shelves. They installed a complete shop fit in a day. We needed a name and came up with IDEA Books (now IDEA: the initials of Angela, me and our two daughters). We opened until midnight, seven days a week. Angela and I took it in turns to work in the store and look after the children. We also took it in turns to completely change the music playing inside and the display in the store window. We each followed our personal taste, though generally speaking we liked the same thing. In our opinion, it was world class from the minute we opened. The first person through the door was Dickon Bowden from DSM. He must have loved it, too, as he offered us a permanent space there. The rest is history. Or Instagram. But that’s another story.

E-mail sent to Christopher Simmonds by Floriane de Saint Pierre’s office, 2014.

Christopher Simmonds, art director

Many times throughout my career I’ve been blessed with good luck. In 2000, I was a first-year student at Central Saint Martins, and the summer break was fast approaching. I was desperate to do some work experience after an uneventful first year. There was a notice on the pin board at the college looking for a fashion assistant at Arena magazine. I was obsessed with Arena Homme + and The Face and thought that the magic of those publications might rub off by being in the same building. I was oblivious to the heritage of Arena, but I learned so much. Helping the fashion director Allan Kennedy and the fashion editor Georgina Hodson, I experienced shoots by David Bailey, Jonathan de Villiers, and Albert Watson. I learned the culture of being on set and what a photoshoot entailed. I was a terrible fashion assistant, but it reaffirmed my desire to become an art director, which was the whole reason I came to London in the first place.

In 2004, my final project on the fashion promotion BA at Central Saint Martins was to produce a magazine. My idea was to do a men’s magazine called He-Man. I produced 2,000 copies – double the print-run for my current publication Print – and enlisted friends to create content. I went around London giving them to newsagents and magazine stalls and fashion outlets. Crazily, they all sold out! One copy ended up in the hands of Joanna Gunn who worked at Lane Crawford. She called me up out of the blue, asking if I wanted to work on a new campaign with the immortal phrase: ‘We have a budget, but we can’t afford Meisel.’ I was fresh out of college and working in a small design studio called Martin Jacobs, so I contacted my more worldly friend Greg Stogdon. From that call, the company Partner + Partner was born. We grew over the years until Greg left for the bright lights of Burberry.

In 2014, with impending fatherhood on the horizon and my time split between freelance projects and being the creative director of Dazed, I was pretty busy. But over the Easter holiday, I was doing a spot of cleaning at home and I fired up an old laptop. It had an e-mail address that I didn’t use anymore, but out of curiosity I had a peek at the inbox. Hidden among the junk was an e-mail from Floriane de Saint Pierre, a prestigious French headhunting agency, asking what I was up to. The email was a few months old, but I e-mailed them back nonetheless. So began my journey towards working with Gucci. I often wonder what might have happened had I not seen that e-mail.

Floriane’s mother, Claude de Saint Pierre, 88, in her vintage Balenciaga egg-shape coat. In Belgrade, July 2019, at the Presidential Palace, on the occasion of President Macron’s visit to Serbia.

Floriane de Saint Pierre, founder, Floriane de Saint-Pierre et Associés

All the credit goes to my mother. She is very intellectual, passionate about contemporary art, and beautiful in a very natural manner: Saint Laurent peasant dresses, striped knitwear with khaki trousers and espadrilles, or a Balenciaga bright yellow egg-shape coat were, thanks to her, my early exposure to fashion. That exposure to beautiful design was combined with the fact that there was nothing frivolous about how she, hence I, viewed fashion. She brought up three children in a completely gender-equal manner. I attended a boy’s school, the Lycée Janson de Sailly, the first year it was open to girls. When I was a teenager, she gave me the best advice a mother can give: choose as a job the thing you like best, or that you feel good at, and which makes you financially independent. And in order to do that, it will be easier if you graduate from a top school or university. I graduated at 20 from ESSEC, the leading business school, and started to work right away. I wanted to work in fashion, but having no idea how a fashion house was organized, I decided to focus my studies on finance. Always useful, isn’t it? And I started sending my resumés for internships. Dior had just been acquired by Mr Arnault, and the newly appointed CFO, Alain Ducray, was looking for interns. I had an interview: it was my chance; I was in. He was amazing; I learned so much with him. I decided on my first day at Dior that I would not leave. I was offered the opportunity to join right after I graduated. All my friends were going on vacation or on round-the-world trips. I so much wanted to work in fashion and I was so happy at Dior, while keeping in mind the wonderful advice of my mother to always be financially independent, so that nothing could distract me. There were several significant people in my entry into fashion: Béatrice Bongibault, then the CEO of Christian Dior, who encouraged me to do executive searches and gave me my very first; my husband, who supported the idea of my launching company when I was 26; Calvin Klein, who picked up the phone himself to give me my first searches in the US, back in the 1990s. And all the wonderful owners and CEOs for whom we have built short- and long-term value, and who have helped us become what we are today. I feel fortunate. I feel that I have worked incredibly hard, and that I still do today. I feel proud of being a female entrepreneur; there are so few of us. I feel proud of having built an amazing team! And I have learned to trust and empower young people, the way my mother and key industry players did so with me, and to admire entrepreneurs in creative industries and family-owned businesses. Today, 70% of the most successful fashion and luxury listed groups are family-controlled. I admire them. They are thinking about the long-term.

Vulcanian + Wizard = A Crazy Good Time. Photo: Galadriel.

Humberto Leon and Carol Lim, founders and creative directors, Opening Ceremony

Humberto: I had a job at Gap corporate when they were opening up Old Navy, and I worked there from store one to store 400. It was a big, pinnacle experience for me because I got to see how a brand was built and grew. I ended up being recruited as a visual director in 2000, and moved to New York to work for Rose Marie Bravo, where I saw the rebirth of Burberry from the ground up, which was super exciting. They went from a nobody to a somebody. That is where everything began.

Carol: I studied economics and international development, did consulting and investment banking and found myself moving to New York in 2000 mainly because I thought one should live in New York. Coming from California, I wanted to try my hand in fashion. But back in 2000, the industry was rooted around prior experience. I was offered a lot of internships, but after working for four or five years I was like, ‘I can’t stay in internships any more.’ I got hired at Bally Switzerland

because it had been bought by a private-equity firm. It understood my background, and was like, ‘This is about thinking about strategy.’ That was my foray into fashion. Humberto and I had met back in Berkeley and kept in touch. In New York, we had a daily lunch meet-up, because I was just a block away from him. We once went on vacation together in Hong Kong, which was one of the pivotal moments. We met a bunch of like-minded people out there who were designing clothes and selling them, or founding magazines, or being amazing musicians. The cultural landscape there sparked the idea of ‘Hey, can we do this?’

Humberto: Back home we working major corporate jobs. We were in a good place, but we weren’t doing anything that was out of the box. We thought that we could contribute something bigger to ourselves and to young designers in New York. There wasn’t a place that housed these interesting conversations, and that opened the door for us to start Opening Ceremony. We wanted a cultural clubhouse where people could present ideas, and it didn’t have to be formalized. The corporate was about building perfect working and we wanted the opposite: something that felt more free-flowing, that would welcome ideas. We came back from our trip and were ready to start something new. We met weekly to look at places and make plans. We were excited: we were both in our twenties, going in and meeting landlords and saying, ‘Hey, can we rent a place? We are going to open a store that is going to bring countries together.’ After seeing the initial reaction from landlords we realized we that we needed to have a business plan. One day I was watching TV and this commercial came up offering help for small businesses. We called them, and they were concentrating on businesses directly affected by 9/11, but they told us about another programme to help us build a business plan. We went there and met this guy called Greg. We told him our ideas for a store featuring all these countries, like in the Olympics, and he just thought we were insane. His advice was to scale it back a bit, and we put together our first business proposal. It still included a lot of wild ideas, but it was definitely more manageable. We went to a bank asking for a $100,000 loan to rent a store. They told us that Carol’s credit was amazing and that mine was basically horrendous, so we needed to figure out a different way to do it. We decided to put up $10,000 each, and the bank gave us a loan for another $10,000 each, and so we started the company with $40,000. We went back to the space we wanted to rent but we were told that it was already rented. Luckily for us, the owners of the linen store next door needed to get out of their lease, so we went there and they gladly accepted our request to lease the space. That started Opening Ceremony. I think it was a certain naivete that gave us the confidence. And because Carol and I knew we could always go back to a corporate job, we didn’t feel like we had anything to lose.

Erdem Moralıoglu, designer, Erdem

From a very young age, I always thought that I would go it alone. In the third year of my BA, while on exchange from Ryerson in Toronto at the University of Central England, I did a work placement at Vivienne Westwood. I spent months there going through the archive, looking at those incredible corsets by Mr Pearl, as well as the shoes and the extraordinary tailoring of iconic collections, like Storm in a Teacup. Working there blew my mind. Maybe it was the idea of ‘Westwood’, of a singular vision that cemented my desire to do my own thing.

It’s hard to isolate a particular moment as my ‘big break’. There are times that felt particularly important, like having my first private clients or seeing my work in the window of Barneys on Madison Avenue in 2006. That was extraordinary; I was working out of a 200-square-foot studio on Mare Street at the time. My first Vogue cover is another one. So is working with Dover Street Market, and my first window at colette, and being included in the Met exhibition Notes on Camp. And dressing Madonna! I grew up on Blonde Ambition, so the opportunity to dress her was incredible. I had to keep pinching myself in the fitting. It came about through Ibrahim Kamara, who had recently dressed her for a music video. He was in touch with her stylist, and we worked together on a dress for the 2019 Billboard Awards.

But the most thrilling thing has to be walking down the street and seeing someone wearing my work. I might see them wearing a top or a dress that I recognize from Spring/Summer 2011, and realize that it’s something someone’s worn for the past eight years. In the end, maybe it’s less about feeling like you’ve had a big break, more about feeling that what you do has really been absorbed into people’s lives and wardrobes. That they’ve had memories in that dress and will pass it on.

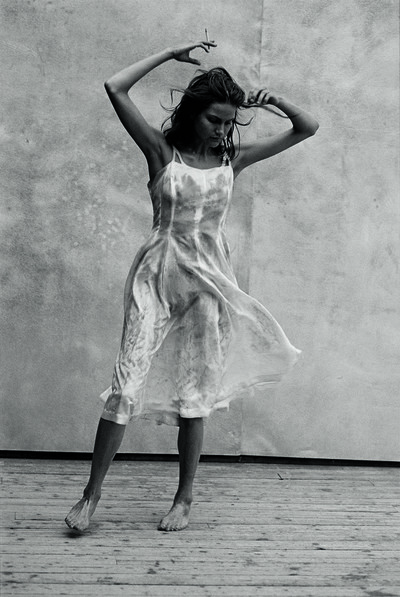

Aleksandra Woroniecka’s first shoot with Peter Lindbergh, Vogue Italia, August 1997.

Photo: Peter Lindbergh.

Aleksandra Woroniecka, fashion director, Vogue Paris

I was 21 when I met Peter Lindbergh through my ex-boyfriend. I was a stylist assistant at the time and had just finished my studies in psychology and linguistics. We got along well and started spending quite a lot of time together. I was very impressed by this charismatic character. A year or two passed, and I started doing little things on my own as a stylist. One day, Peter told me that he really liked the work of Pina Bausch, and he would like to do a test with me inspired by her choreography. A test with Peter Lindbergh? It sounded crazy! Peter Lindbergh doesn’t do tests, but he does make top models… I went to a thrift shop and got two white slip dresses. We shot two models in those dresses soon after, and the pictures were beautiful. Franca Sozzani saw them and decided to publish the whole story in Vogue Italia. It was incredible to be included in such an adventure: two of the most talented and iconic people in the fashion industry trusting me more than I trusted myself. That was just the beginning of the adventures. I thank Peter forever for trusting me and for seeing something in me that I couldn’t see myself. He kept believing in me and pushing my boundaries throughout my career.

Alexandre de Betak in his twenties.

Alexandre de Betak, founder, Bureau Betak

Many years ago, I met a young Spanish designer named Sybilla Sorondo. The job I’m doing now didn’t exist yet, art direction was usually done by the designer. When I started at Sybilla, I kind of invented this job for myself. I had studied in Paris and opened my first office very early on. It went really well, but the economic situation in Paris at the beginning of the 1990s wasn’t the best. Also, my job didn’t really exist in Paris at that time. I felt like people wouldn’t understand my ideas for events, shows and designs. They would usually suggest that I do PR, too, because back then PR organized fashion shows. I wasn’t interested in PR, though: I wanted to do the creation of the show and the production. So, when I was 20, I left Paris for New York. When I got there, I just told people ‘this is what I do’, and even though it is still a big cliché today, that classic idea of the American dream does exist regarding your life or your career. I arrived in New York and said, ‘I do the concept of the design and the production of the fashion shows.’ The companies there said, ‘let’s try it,’ as opposed to, ‘no, you can’t do it like that, we need to give you something else to do,’ which is a very French thing. Ironically, my first client wasn’t American; it was Prada. I did Prada, Miu Miu, and then Donna Karan, who gave me complete freedom to reinvent her ways of showing. All of this happened at a time when New York Fashion Week had just started. With the ambition

of a very young European boy, I guess I just said, ‘I’ll show you how I think you should do this show.’

Lucien Pagès with Sarah Andelman. Photo: Saskia Lawaks.

Lucien Pagès, founder, Lucien Pagès

Growing up in a village in the south of France, I think my lack of access to the fashion world fuelled my desire to be part of it. I decided that studying fashion would give me the greatest chance of gaining that access. I read an article about the best schools and the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture was right at the top. People told me it was a super chic, super snobbish school and that I’d never get in, so I knew I had to go there!

I interned at Dior with Gianfranco Ferré, and with Yves Saint Laurent himself in his studio, but I very quickly realized that design wasn’t my skill. I’m lucky that happened early on. I came to assist Marc Ascoli by accident. I met him and we hit it off. Marc was married to Martine Sitbon, the designer, and their offices were in the same building. I helped her with her shows, and started to develop relationships with the press and celebrity stylists. It came very naturally to me. My first big break came through Adam Kimmel, my first real client. He really cemented my being a PR. And, of course, Vincent Barré, the furniture designer. He was actually the first one to tell me that I should be doing PR at all. But the most significant break of my career came when Sarah Andelman from colette asked me to invite the brands I was working with to do a takeover of the store. She texted me right after Fashion Week – I was totally exhausted – saying that she had a crazy proposal. I went to see her, and she told me she wanted to bring all of my clients to the store; even the ones that weren’t selling! I was a bit scared, as I’m usually behind the scenes, but I realized that the industry was undergoing drastic change, and this was something that had never been done before. At that moment, it was what people wanted. It was very emotional, as it was something really tangible for me, for once. There was such a sense of goodwill about the whole experience. It was a project among friends. Sarah was a friend of mine from before, and I brought M/M on board for the visuals, and Michel Gaubert for the music. It was a good thing we did it when we did: ‘Les Vacances de Lucien’ was announced on Monday, and on Wednesday, Sarah announced that colette was going to close!

Mark and Bibi Borthwick, Paris, 1995.

Mark Borthwick, photographer

My life’s big break came with the virtues of my daughter Bibi’s birth –

Embedded within the sincerity of trying to find a sense of meaning to life. These were the days of true unfounded joy…

creating an awareness that the costume of one’s soul’s true heart creates from all source an origin

Whilst nurturing image’s that lay at heart of one’s life story –

Thus within the realms of becoming a photographer

Systematically upon the virtues of never having a big break –

I would joyfully exclaim…

That I was anti that – especially drawing attention to… primarily aware that it was the cracks in the streets – and the

marks left from a bed sheet’s replace. That left me wandering upon shores wasted alarming voices. Calling aware’ing to

listen – For it was that – That was ordained ordinary that conferred to Mark my way –

Whilst encouraging an emptiness that space liberates

between the weight of a magazine’s pages.

Reflecting now – I was fortunate… for most brands would not

come near me… was it that I was creating portraits that question – perhaps…

Without the pursuit of an answer – Answer being the currency that provides images that corresponded to consummate

their consumerist voice –

That was initially pointless since they already existed –

whilst… Advertising became the answer…

No different from today’s narcissistic realism… and the voices

of social media commentary of the self’s tireless examination

– exclamation. That’s profoundly a commentary’s purpose to

fully demand an advertisement of the self –

It’s with discernment – that I was blessed to free its effigy of all

confine’s – hence at the time without a sense of known

One enables an image to exist upon its own volition – hence

by coincidence you make it your own… over time.

Recognition always made me feel awkward – whilst perhaps

I was just awkward to begin with … let’s face it the system’s

full of limitations.

One’s seduced to participate hence create a picture that’s

stuck within the confines of its lost identity… as a kid I was

aware one has to create.

Their own rules so to diminish all sense of control over the

image… Imperative to say did I think I was any good at it –

defiantly not… For it was – is – the vulnerabilities that I was

consumed by… and the act to never know nor administer a

sense of command.

Did I know what I was doing?… certainly not – for that was

where the joy lay among the virtues of its surprisal – its loss

of authority…

Nurturing its essential territory… of the unknown –

It’s crucial to say that I learned to be myself by going directly

to the source… liberating the picture perfect from the confines of its own synthesis.

Of other voices implementing their egos upon it… Meaning I

understood so clearly that to desire an image that questioned

within the realm’s. Of what constitutes as a fashion photo

graph… one had to take away what exists to curiously imple

ment another choice. Hence in most cases no hair nor make

up – in full appreciation of the beauty that one holds from

within – that was my initial begin –

Love of the untouchable… No models if possible – nor faces

known aware they belonged to the face of the industry and

were already marked by an amalgamation of photographers’

identities… hence not my territory – and most importantly

no styling – For I became aware that the core of my heartfelt

interest working within in the margins of fashion –

Was the craftsmanship behind the story revealed within the

clothing… unravelling…

History and the origin of cloth itself… Hence by taking away

what’s known…

The image is free to grant its own consummate voice.

So… Yes eye’m anti the system – for it fails as it dictates –

hence loses its identity through its domination –

Through its lack its relative relation to banish its formidable

voice that’s the origin of creation…

For the heart of a creative soul is to create from a place that’s

one’s own…

By example, today the fashion industry is tirelessly repetitive.

Its loss of identity feeds the margins of its own mediocracy –

Its commerce over curiosity – its known acknowledged

knowledge invested over innocence – And yet… eye see… as

I feel… talents spawning from branches yawning their intimate-animate stimulations awakening one… to leave what’s

left behind…

For it’s time – to look forward to the new and not replicate the

old for the sake of its nostalgic obviousness. It’s time to liberate the portrait itself – its transient likeness its amorphous

mirrors conception – perception’s tireless masks impression

only amplifies transition’s transporting deriving…

Through the transparency of one’s question – one sees

through without knowledge known – therefore reacclimating what’s known.

Lovemark’s x

Summer 2019. Photo: RIstudioberlin.

Stefano Pilati, founder and COO, Random Identities

When I swam in Giorgio Armani’s pool. Or when I finally managed not to be criticized for the cappuccinos I made for Miuccia Prada. Or my first kiss from Kate Moss. Or rehab in 1988.

Thom Browne and Harry Connick Jr. attending the CFDA Fashion Awards at the New York Public Library, June 5, 2006.

Photo: Billy Farrell/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images.

Thom Browne, founder and chief creative officer, Thom Browne

In 2006, after years of most people not really understanding my approach to fashion, and my collection being considered somewhat out of touch, I was recognized by the CFDA and nominated for the menswear award, up against the legend of American men’s fashion, Ralph Lauren. It was surreal, as I had grown up wearing Ralph and thought of him as an icon. Ultimately, winning the award that night was something that changed my perception of how people thought about my work. The whole experience was career-changing. I suddenly felt that what I was doing meant I was included in the group of people at the CFDA Awards that night.

Etienne Russo (right) with Dries van Noten (second from left) in Florence, for the Dries van Noten Spring/Summer 1996 menswear show, June 1995.

Dries van Noten Archives.

Étienne Russo, founder, villa eugénie

It all started very organically. In the mid-1980s, there was a strong creative movement in Belgian fashion at the time, and I became part of it, first as a model, then by meeting the fashion cognoscenti in the club scene. I was creative director of a Brussels nightclub equivalent to Le Palace in Paris and I took care of the parties. It quickly turned into my laboratory. I would organize fashion shows and young designer contests at the club while working closely with Walter Van Beirendonck and Dries Van Noten. I collaborated with Dries as his model and followed him around Europe, doing showrooms. At dinner, we would dream about what we could do for his shows. My ‘big break’ happened one day in 1990, when Dries said: ‘Étienne, I’m about to do my first show in Paris. Do you want to do it?’ Of course I said yes,

not knowing exactly what I was agreeing to and where it would lead me; but one thing was clear: I definitely wanted to be part of this fantastic, creative Belgian movement. Today, villa eugénie has offices in Paris, Brussels and New York, and operates beyond the fashion world to create and produce events for luxury industries and large-scale private celebrations. We are constantly expanding to new areas of expertise, much to my great delight!

Colin McDowell, fashion writer

A life based on a mistake is not necessarily a doomed one. In my last year of school I wanted to go to art school, but was persuaded to go to university instead. I loved it but my heart was still in art; I did nothing about it for far too long. After leaving university, I went into the army and when I came out I taught, I acted and started down the long road to debauchery that finally led me to Rome in the 1970s. Paradise. I became a teacher – who doesn’t when they arrive without a word of the local language – but a friend, who had noticed I was always drawing when I wasn’t working or staying up half the night behaving badly, gave me a copy of a glossy fashion magazine called Linea Italiana. That was that – I was in the rag trade.

I designed fabrics, edited and drew for a trade magazine for Japan, but then came the big break: I was interviewed by a couturier called Pino Lancetti, from whom I would learn the magic of couture. I then moved to work with Laura Biagotti, the ‘Queen of Cashmere’, and learned the ways of a successful commercial designer.

I was in Rome for 10 marvellous years tasting its unique, joyous lifestyle of sun, food, wine and sex, all of which in those days were the best in Europe. I used to stay up until dawn, chasing the will-o’-the-wisp of bodily joys! Then it was time to return to reality.

Back in London, broke, I was lucky enough to be asked to write a piece for the Observer about Italian fashion. In the immortal phase of Diana Vreeland, who I knew well, the Italians were just beginning to prance, opening shops in New York and London so I was asked to write more for other newspapers. Another door had opened. Then Saint Martin’s asked me to give some lectures about Italian fashion; that led to a series of lessons about the history of fashion, which is when I first encountered John Galliano and Hamish Bowles.

Then a real job: a stint as the fashion writer for Country Life. I loved it, although I always felt my readers were only really interested in wellies, tweeds as heavy as wood and the-bigger-the-better Barbours! I ignored that, did the shows in Paris, Milan and Europe and actually had two fashion covers, unheard of in a publication that was renowned for featuring dogs, grand houses and ‘debbie’ girls in pearls. I found it fascinating, but a new editor came along and it was hate at first sight, so I was on my bike before I got my marching orders.

Shortly after that Jeremy Langmead, editor of the Sunday Times’ style section asked me to write for him, which I did for at least a dozen years with various editors, until I gave up a few years ago.

I have had a marvellous life – and I am still enjoying it even if I’m no longer at the coal face. Today, I’m writing a new book for my publisher, Phaidon, which should be out at the end of next year and planning a final book, a ‘warts and all’ biography – if I don’t die before then.

Julien Dossena (centre) sat next to Marie-Amelie Sauvé (facing camera, pointing).

Courtesy of Julien Dossena.

Julien Dossena, creative director, Paco Rabanne

My first big break in fashion was when Marie-Amélie Sauvé called me to help her at Paco Rabanne. She put her trust in my work and together we set up the best team: Ashley Brokaw, Pat McGrath, Paul Hanlon, Morgane Denis, Surkin. It’s still such a pleasure to work with them. We’ve done 13 shows now, and when I think back to our first rehearsal, at a time when nobody expected anything from the brand, I feel really touched by the commitment and faith we all had. I am so proud that they were prepared to go down this route with me, and I will always be grateful for their brilliant work and talent.

Photo: Daniel Beres.

Alessandro Sartori, artistic director, Ermenegildo Zegna

I was 15 when I made my first suit. I did it by myself. It took four months and it was not very nice, but I did it. From that day on, I understood that dressing people is the way I could best express myself, and I decided to devote my life to designing clothes. That first vision of my future was my defining moment.

An early Craig Green look, 2012.

Photo: Craig Green.

Craig Green, designer

In 2012, I had just completed my MA at Central Saint Martins. Louise Wilson introduced me to Lulu Kennedy and Charlie Porter at the CSM graduate exhibition, and they invited me to join the MAN initiative at Fashion East. I was in the process of setting up my own label, and their support and encouragement at that early stage enabled me to start my brand and be where I am today.

Renzo Rosso (standing, raising his arms).

Courtesy of Renzo Rosso.

Renzo Rosso, President, OTB

I entered the fashion world by pure chance. My parents wanted me to study, but I wasn’t really interested, so I researched what was supposed to be the easiest school to attend. I heard about this fashion manufacturing course; I enrolled and I quite enjoyed it. While I was waiting to do my military service (it was still compulsory in Italy in those days), I took a temporary job as production manager of a small unit producing trousers for Genius Group, a company run by Adriano Goldschmied. I was young, I wanted to enjoy life and I was not much of a hard worker, so after a while I got fired. That was the moment my true motivation kicked in.

I wanted to prove them wrong. I asked for a second chance and agreed to base my salary on piecework. The first month, I multiplied my original salary by 10. I did that for several months in a row, and then, a bit more confident, I resigned. Adriano asked me to stay on and become a partner, which I did. Together, we created many brands, one of which was Diesel, of which I took full control a few years later. This picture is of those times: a bunch of crazy, fun, visionary young people, obsessed with denim and casualwear, who contributed to changing fashion culture.

Photo: Julian Hargreaves.

Gabriele Moratti, creative director, Redemption

I’ve never paid much attention to fashion in my personal life; my second skin is a pair of jeans and the first T-shirt off the pile. My initial interest in fashion came through photography. I fell in love with the medium when I was around 9 or 10 years old and at my grandparents’ house for Christmas dinner. My grandfather received a beautiful book as a gift: a retrospective of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s work. Instead of going to play with my cousins and siblings, I was glued to that book. I can vividly remember being transported into new worlds. And, of course, growing up in Milan in the 1990s, I was surrounded by billboards with images by Peter Lindbergh, Richard Avedon, and Helmut Newton.

I didn’t consider fashion as a potential career path until much later, when we founded Redemption. It was a completely different company at first: we made motorcycles. Looking at case histories of motorcycle companies, I realized that most of their revenue came from the merchandise rather than the motorcycles themselves. And then I had an epiphany while watching The Pink Panther. Seeing Claudia Cardinale lying in front of a fireplace in this beautiful hotel in Cortina d’Ampezzo, I realized that if there was something I wanted to do for the rest of my life, it would be to try to dress her.

The company was founded with the idea of giving 50% of our profits to charity, and we knew we wanted to make an impact. A disruptive business has to be in the right place to be effective, and fashion is ideal for a couple of reasons: it’s the second-largest employer in the world, so if you want to create impact by example, that’s where you do it; and it’s the second-largest polluter in the world, so if you want to minimize the human impact on the environment, it’s a good place to do that, too!

My parents gave me an appreciation of the value of philanthropy and culture. I guess you could say that was my big break. Aside from them, there are no specific people or events that I can mark out. The barriers to entry in the fashion world are pretty high, and we fought hard for what we now have. That’s normal in life: you have to work hard if you want something. There’s no substitute, unless you’re a creative genius. I’m far from being that, so my ethos has always been to work twice as hard as everybody else.

Skeleton dress from Iris van Herpen’s ‘Capriole’ collection, Autumn/Winter 2011.

Photo: Bart Oomes.

Iris van Herpen, founder and creative director, Iris van Herpen

My big moment came in 2011 when I was invited to do shows in Paris by the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode. My audience and clientele became global, and it became possible to dedicate myself to what I love most: the art of fashion.