Pierre Hardy on 20 years of fashioning footwear.

By Éric Troncy

Photographs by Erwan Frotin

Styling by Azza Yousif

Pierre Hardy on 20 years of fashioning footwear.

A dancer and costume designer for the Matt Mattox company, Pierre Hardy hadn’t really planned on becoming the Pierre Hardy who created his own shoe label 20 years ago. It was there that he designed the now celebrated talon lame or blade heel, an essential shoe whose aesthetic statement still feeds into his work today, and which he has rereleased for his 20th ‘anniversary’ (a word that makes him imperceptibly grimace). Less moved by the past than the future, the thing he finds worth celebrating is when the contemporary world means fantasy, freedom, creativity and invention.

He often talks about working ‘on the margins’, by which he means the margins of his chosen discipline’s mainstream, but it strikes me that he uses this word to evoke other edges, the liminal spaces occupied by aesthetics and behaviour, which shelter those who reinvent the world or at least do all they can to avoid its routines.

Pierre Hardy was appointed women’s shoe designer at Dior ‘by complete chance’ without ever having really designed shoes; he stayed from 1988 to 1992. Then, in the early 2000s, he created a revolution in the world of luxury shoes with his ‘sneakers not made for running’, the start of a movement whose effects are still being felt today.

A few years ago, he and I met at his former offices in the 10th arrondissement, near the Canal Saint-Martin in northern Paris, with a view to publish ing a catalogue of his work. This time around, in early October this year, we sat and talked in entirely different surroundings, his new offices on the more classically chic Left Bank, behind Place Saint-Sulpice. A change of neighbourhood that feels not without a certain significance. “Marion found it!”, he says in his defence, laughing loudly, referring to Marion Daumas-Duport who oversees Pierre Hardy’s communications and has worked alongside him for as long as I can remember. The garden at the back of his new office looks like a rural schoolyard from another century. Planted with big trees, with a bench and a birdbox, it has a sort of divine tranquillity that contrasts with the bustling city outside. It’s an unexpected decor, because the move to these comfortable, bourgeois surroundings feels somehow in visceral opposition to Pierre’s own nature. Behind the designer Pierre Hardy, the impeccable businessman deeply connected to contemporary reality, lies the other Pierre Hardy: a man who loves his freedom and is proud to reject convention.

Éric Troncy: Pierre, the last time I came to your offices to talk to you, we were doing a catalogue of your work, and you were in offices near the Canal Saint-Martin. And here you are on the Left Bank!

Pierre Hardy: [Laughs] It’s pure chance, like so many things in life. It was never planned like that. We wanted to get closer to the centre – without really knowing which centre – and then we found this place. I’m not really very Left Bank, but to be honest, it doesn’t really change much on a daily basis. Not that we function in a vacuum, but there’s a laboratory aspect here, on a low-level scale. In the same way, I’m not sure that the 10th arrondissement influenced us that much. The offices were quite unusual, not really typical of that arrondissement; it was like a cross between the Palais Garnier and Italy. But I don’t really believe in that permeability – the place I work in has little impact on what I do. I’m far more aware of the bigger picture: Paris as a whole. It embodies a certain taste, proportions, a certain light, in short, all the postcard views we know, whether we’re for or against them. I wouldn’t do the same thing in New York or Los Angeles, obviously.

You live mainly in Paris, right?

Yes, I was born here and grew up here. Now I live here, and I never go away for the weekend. That said, I would like to live in Los Angeles. Most of my New Yorker friends have moved there now. It seems less preformatted. And I think it’s amusing that you get offered a spliff instead of a coffee when you do business meetings there. New York became a model, and then its own copy.

Isn’t Paris a bit like that too?

Sure, but in Paris there’s a greater depth of field, historically and culturally, and that nourishes the city from the inside. To me, New York seems more 2D. But Paris, like other cities, has really changed! London was interesting, but not any more, New York was interesting, but not any more. There’s no longer any fashion in New York. There are markets, businesses, but there’s practically no more creativity. The city itself is much less creative. Everything’s been pruned; it’s too clean, safe, rich. In the art world, the biggest galleries are there, but it’s a metropolis that functions like a monopoly. There are three huge galleries that crush all the others. For fashion, it’s similar in Paris, three or four big groups control everything horizontally and vertically, while the rest are just trying to get by.

‘I didn’t know anyone who made shoes. Then in 1988, someone asked me, ‘Do you want to come and do shoes at Dior?’ And I said, ‘OK, why not?’’

Aren’t you partners with Hermès?

Yes, after working together for a long time, Hermès became a minority shareholder in my business. We’ve known each other for 30 years; it’s a family, and that changes everything. They have real savoir-faire, they’re not industrialists or investors. They’re people who know how to make a product, and how to sell it, they are very pragmatic.

Doesn’t the idea of ‘savoir-faire’ define you pretty well?

Do you think? And yet I don’t know how to do much, and definitely not a shoe. I know how it’s done, but I don’t know how to do it. But it’s like success or love, it’s other people who can have an outside opinion, but on the inside, you’re never sure of anything.

You don’t know how to make shoes; is that why you carry on doing it?

Probably. Doing something we know how to do is often about doing it the same way. I have an infinite respect for artisans, and the more they do one thing, the more they know how to do it in a masterful way, but I think that expertise is also a prison. And I have a problem when it comes to comparing art with applied arts. I don’t think they’re really the same thing.

What you’re saying makes me think of a German painter, Charline von Heyl, whose work I really admire. She tries to never do the same thing twice, whether it’s a style or a technique. There are

no two paintings alike, or which use the same savoir-faire. It’s a pretty demanding approach to take in an era when ‘the market’ requires every artist to have their own identifiable style. But at the same time, the history of 20th-century art is all about the emancipation of conventional savoir-faire – that said, though, if you’re a good potter, you can still be shown in a big contemporary art museum! Savoir-faire is back.

I think Jeff Koons’ bouquet of tulips, which has just been installed in Paris near the Grand Palais, is a good example. It’s been perfectly made, there’s no doubt that he works with the very best artisans, but the sculpture is pretty ugly. Mainly because the hand is so badly designed; its gesture is clumsy. Yet I’m the first to say he is a contemporary genius! I remember the first time I ever saw his work, it was at the same time as Haim Steinbach – same thing, impeccable production, high-end artisans – at the Pompidou Centre in the late 1980s…

You saw that exhibition? I remember it perfectly, too. It was called Les Courtiers du désir and it was a group show dedicated to young American artists; it was 1987. In retrospect, the Pompidou Centre was really at the cutting edge – is it still? – because Jeff Koons’ now-famous Rabbit was in that show,

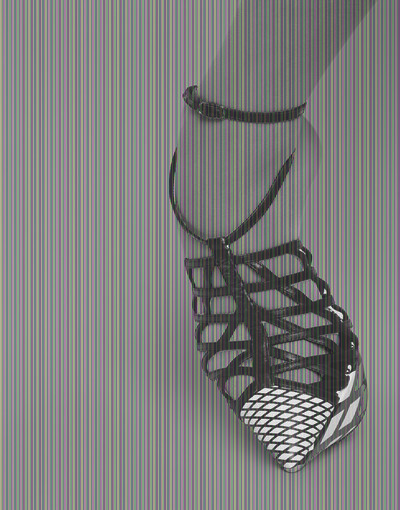

and it had just been made and shown for the first time a few months before at Sonnabend in New York. I’ve got a funny story to tell you about it: one of those Rabbit sculptures recently sold at Christie’s for $91 million. At the time of the exhibition, the acquisition committee at the Pompidou Centre was offered one for 80,000 francs, which is about €15,000, and the ‘experts’ on that commission deemed it of no interest! So, here we are in your office and on your desk is a shoe with this heel… I get the feeling that in your designs it’s all about the heel . You’re rereleasing the blade heel from your first collection, which was 1999/2000.

I haven’t found anything better since then; nothing is more radical, simple or efficient. The heel is crucial — that’s what it’s all about because there isn’t much room for play elsewhere. Of course, there is everything that goes on above, but the creative space is very minimal. The heel is an empty space that can be filled with a ball, a cup, a Camembert, a roll of sticky tape – anything can be a heel! It’s the only little space that is really free, within the rules of load-bearing points. It’s the only virgin space where you can invent things and at the same time, it’s very, very constrained.

This re-edition of the blade coincides with an anniversary: 20 years of the house of Pierre Hardy.

I’m not a huge fan of anniversaries, and this doesn’t really strike me as one in the sense that it isn’t the 20th time I’ve done the same thing. What I’m doing today is nothing like what I was doing 20 years ago. I was very naive! Today I can’t imagine how I was able to put 15 things on a bench and say, ‘Come on and see, they’re amazing!’

‘I have infinite respect for artisans. The more they do one thing, the more they know how to master it, but I think that expertise can also be a prison.’

For someone opening a gallery 20 years ago, the promise was also very different from the reality of being a gallerist today. The very idea of almost daily long-haul journeys would have seemed utterly far-fetched: Monday in Hong Kong, Tuesday in New York, Wednesday in London and Thursday at another fair somewhere in the world, without counting the private views of artists the gallery represents and where the gallery has to be represented. The people who 20 years ago chose this job or this sort of relationship with artworks have had to adapt or disappear.

Are you thinking about the galleries, like Air de Paris, that were all located together in the 13th arrondissement?

Air de Paris is a bit different because it’s succeeded in keeping its integrity in regards to the initial commitments. Sure, it’s a gallery that does all the necessary work today, the incessant representation, but it hasn’t multiplied the number of artists it represents by 12, which is what most of its foreign counterparts did to satisfy the different markets. It doesn’t have 10 artists for the Asian or Gulf market; it hasn’t opened two, three or four branches on several continents. Others took a different gamble, Almine Rech, for example, who was also in the 13th arrondissement now has galleries in Paris, Shanghai, London, New York, and Brussels. They’re two different conceptions of

this profession, and whichever one you chose, you have to do it thoroughly! Fashion has changed too, hasn’t it?

Fashion is an industry with suppliers, producers, factories, sales spaces, means of communication, with groups that master everything, from the herds of cows to the tanneries to the sales outlets in cities all over the world that reproduce the same layout and, incidentally, have a dramatic impact on property prices. For groups that are worth $5 or $10 billion, a boutique costing $5 or $10 million means nothing, but for independent brands, it’s become impossible. There’s an exclusion based on a financial power that didn’t exist before.

How did you start making shoes?

By complete accident, and it would be fair to say, ‘step by step’. I was a student at the Beaux-Arts, working towards becoming a teacher with a degree in fine art. Fashion for me was a distraction, but I think when you embark on a certain path, then it becomes interesting.

Did you know people who were already making shoes, and say to yourself, I’d like to do that?Generally, that’s how the vocations of an artists are born, we want ‘do that’, or belong to that club.

My friend [artist] Bertrand Lavier likes to say that you don’t become a painter because you saw a lovely sunset, but because you saw a lovely sunset painted by Turner…

I didn’t know anyone who made shoes! And then someone said, ‘Do you want to come and do shoes at Dior?’ And I said, ‘OK, why not?’ It was the end of Marc Bohan, when Gianfranco Ferré arrived; I think it was 1987.

You knew Marc Bohan?

I met him once. He talked to me while touching his hair and looking in the mirror behind me. It was horrible.

You weren’t impressed by him then or the others afterwards at Dior?

You know what, I didn’t take it that seriously. It’s hard to explain today, but I really enjoyed it. I worked with a gang of friends, my friend was in charge of the studio, and at no moment did I say to myself that I was going to design the biggest collection of shoes for the biggest and best-known brand in the world. Because that’s what Dior was at that time!

Those were good times, weren’t they?

Tell me about it! I never once saw anyone from the HR department. And the weight of decision-making wasn’t at all the same. Today we’re in a market, and each collection is marketed, locked down, calibrated; it wasn’t like that before.

That happened to a lot of disciplines. It happened to music, movies, too, fashion obviously, and more recently with the visual arts, but now it’s over: it’s an industry with its marketing rules and big groups dominating the market. That said, it’s just another framework to work in…

Exactly. You just have to say that you work ‘in the margins’; there isn’t really an avant-garde anymore. Cinema used to be a discipline with a real avant-garde, but that’s become marginal, too.

‘People mourn Yves Saint Laurent, but I remember his Picasso and Van Gogh collections – horrible, sequinned reproductions on suits with old-lady cuts.’

In all disciplines, when newcomers ape the idea of avant-garde within a context that’s become an industry, it’s all a bit pathetic. Rei Kawakubo can continue to do it because she always has, but maybe that doesn’t apply to someone like Iris van Herpen. I remember an interview with Kawakubo where she said very clearly that art didn’t inspire her at all and had nothing to do with her activities. What I find amusing today is how all the fashion designers claim to be so inspired by contemporary art, and in fashion magazines there’s more to read about art than about fashion… Are you inspired by art?

Definitely, but not in a literal way. Apart from a few specific cases of direct citations, say Lichtenstein or Sol Lewitt, it’s a complex alchemy, a bit of what I see, a bit of what I retain. They’re more like filters. I don’t have archives and I don’t do mood boards. If I do them, it tends to be afterwards, to explain where something has come from. It’s never the inspiration, and never as a literal translation. Today, people mourn Monsieur Saint Laurent, but I remember those Braque, Picasso and Van Gogh collections, and they were horrible, sequinned reproductions on suits with old-lady cuts.

Is Pierre Hardy a big house now?

No, it’s a small house, there’s only about 25 of us; it really is a ‘marginal’ discipline. Even Manolo Blahnik, who is much better known than me and has been around for much longer, is marginal. But that’s the paradox of fashion: you have to be both marginal and like everyone else.

Is there more freedom in the creation of shoes than the creation of clothes?

No. If you visit a department store in New York or Paris, the brands are doing roughly the same thing. It’s quite similar to the 1950s when there were essentially only court shoes. Now there are biker boots, court shoes, hiking boots, sneakers, ballet flats, loafers, but all the brands look alike.

Ah yes, sneakers. Let’s talk about them, because it’s all partly your fault, isn’t it? What made you think about making a sneaker that wasn’t for running, at a time when no one else was doing it?

Firstly, because sneakers represent eternal youth! That was probably the initial motivation. I remember when we used to fix wheels to them to make roller skates… It’s a whole dynamic unto itself. A person wearing black Oxfords instantly feels 10 years older. That goes for the body – because you don’t walk the same way when you’re wearing sneakers – as well as the imagination. Like hyaluronic acid or Botox, it’s just an illusion, but a very good one. And there’s more possibility for expression, especially with men’s shoes, where the choice can be quite narrow. Sneakers meant men were allowed to wear other colours than black and brown. It offered men easy access to fantasy. And

it also led me to discover another skill, because designing sneakers is nothing like designing a leather shoe. It’s a different timescale, different materials, you have to do 3D drawings and 3D printed mock-ups to check all the volumes, choose the plastics to inject; it’s like a piece of furniture! It’s got nothing in common with the shoemaking profession. It’s really fun, as well as being very restrictive: the technical specifications sheet for a sneaker is 25 lines long. This part is in such and such a material, this part in something else, and then this bit in something else again. The game lies in the combinations, in the accumulation. A sneaker is a construction. I get the feeling we’re going back to simpler things, more minimal, more monochrome, less voluminous, but the one-upmanship has gone a very long way, especially in terms of ugliness! Ultimately a sneaker is about restraints and the aesthetics often result from those restraints, from a technology or a lack of technology. There are lots of things whose form derives from the very materiality, which creates a certain shape and this shape then becomes an aesthetic. The eye adapts and ends up finding it beautiful, or at least we believe it to be beautiful. The best comment I ever heard after a show was Catherine Deneuve when a journalist asked her what she thought of the collection. ‘We’ll get used to it,’ she said! That’s a crazy intelligence.

To come back to this anniversary…

The good thing about it is that it forces you to look at the past, which I’ve now done and I’m ashamed of nothing! Will the blueprint we’re using at the moment also allow me to do things that I’ll be proud of in 10 years’ time? I hope so. I also like being able to tell myself that I could stop everything right now, in one fell swoop, with a splendid gesture, but that would be really stupid!

‘The best comment I heard after a show was when a journalist asked Catherine Deneuve what she thought of the collection. ‘We’ll get used to it,’ she said!’

Like colette?

Pierre doesn’t realize I’m talking about the Parisian store, not the celebrated French writer, and recites a quote by her, printed on a business card on his desk: ‘Il faut avec les mots de tout le monde écrire comme personne’ – ‘One must write like nobody else using everybody’s words’ – before realizing the mix-up and continuing.

Ah! I don’t know what Sarah [Andelman]’s motivations were, but when you know that the boutique across the road has sold for €5 million and it was 40 square metres, while hers was nearly 300 metres, you might think twice about continuing to sell fashion. We’re at the heart of the question: will the looming logic, the logic of this world in which fashion now exists, allow things to happen or will everything be broken and reconstructed?

I have to tell you about a conversation I had recently with Christian Boltanski, who said that in his opinion in 50 years’ time, if there are still museums, there will be a room with two or three works from today without their creators’ names and instead just a sign saying, ‘contemporary art’. And it’s possible that he’s right, again. The history of art, which has been the backbone of this discipline – currently known as ‘contemporary art’ – has been reduced to the level of a mood board, but it could get even worse, and history might be rewritten. It probably will be. My friend, Philip Van den Bossche, curator at the Mu.ZEE in Ostend, posted a picture on Facebook of Brancusi’s Endless Column, and wrote, ‘The most important sculptor of the 20th century’. Someone responded writing: ‘Brancusi was not the most important sculptor of the 20th century. When people come across these offensive

racist idiocies, they have a responsibility not to reproduce and further perpetuate them.’ In other words, considering Brancusi as the greatest sculptor of the 20th century is racist because he is white. Today, as Bret Easton Ellis masterfully proved in White, ideology has replaced aesthetics, and we’re not immune to a total rewriting of history. When they discover that the wood used for Rothko’s paintings has contributed to deforestation, will he be taken down in museums? And aren’t the lead paintings of Keifer a terrible health risk?

Between leather and polymers, that’s one of the major issues today. People are eating less meat, so there are fewer herds, and with intensive rearing, the herds are malnourished, so the skins are of bad quality, and the animals are badly treated, so the skins have scars. Leather is less acceptable, and the tannery industry is extremely polluting and requires huge amounts of water. Even if better processes are being put in place, it takes time. Luxury brands are criticized, but they’re actually the ones really thinking about things in a constructive way. I’m making things on the margin. One group might make

3 million pairs of one model a year; I only make 3,000. I make to order; I never throw anything out; I have no stock; nothing goes unsold – there’s very little waste. That’s not an excuse, but I’m doing my best. There’s no alternative to leather that’s just as comfortable. Current research into producing synthetic leather by cloning synthetic cells isn’t yet developed enough: it takes a year still to make 10 centimetres of material that’s horribly expensive, ugly and unworkable. The sneaker is an answer in some ways, because there’s no problem of arching and shaping, the upper can be produced in a clean way from synthetic materials, and it’s adapted to all genders and all climates.

You mention genders, if the vegan consciousness is a characteristic of the era, so is gender fluidity. The idea that being born a boy or a girl is no longer something you take for granted is new. How do you deal with that in a world of ‘men’s’ or ‘women’s’ shoes?

In one way, it’s very simple because girls have always worn boys’ shoes. In another, it’s more complicated, but there are collections for ‘men who think they’re men’ and others for those who feel a bit less alpha. These aren’t men who are going to wear women’s shoes, even if women’s sizes are getting bigger; today we go up to a 42. The idea of being born a boy or a girl and not taking it for granted isn’t really that new, it’s just that before you had to shut your mouth and act ‘as if’ you were one or the other! They hid, they made do, and sometimes they committed suicide. With gender fluidity, it’s the fluidity that is so interesting, not whether boys are wearing girls’ shoes, and it doesn’t escape market forces: as long as it only represents 5% of the global market – if indeed it does – there will only be 5% of collections that address this population. In fact, to be honest, I don’t really address

anyone in particular. And anyway, the standardized world has exploded!