For Francesco Risso, Marni is a platform to explore the outer limits of consciousness.

By Tim Blanks

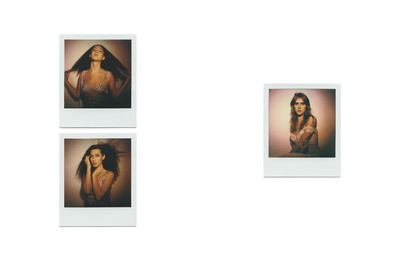

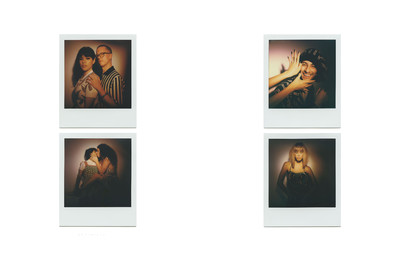

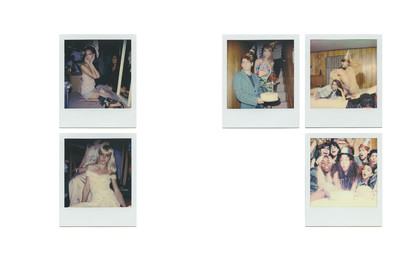

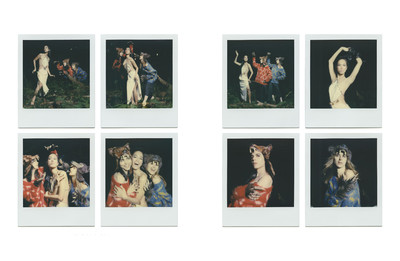

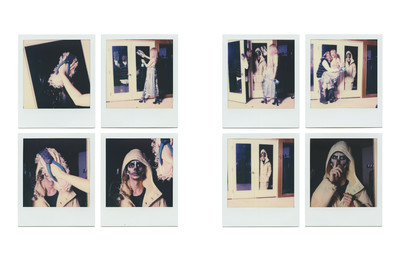

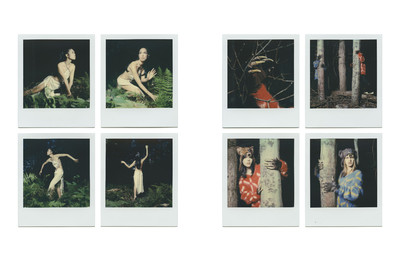

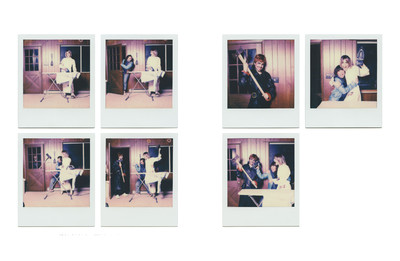

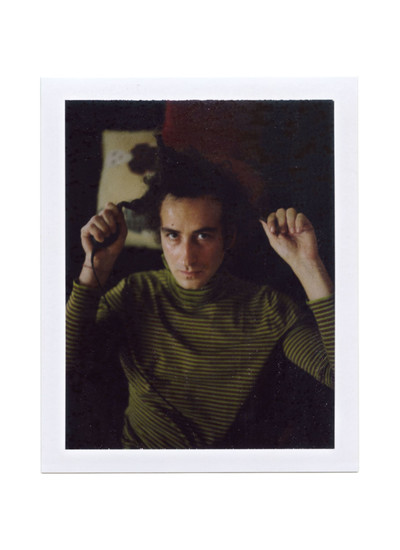

Photographs by Ethan James Green

Styling by Tom Guinness

For Francesco Risso, Marni is a platform to explore the outer limits of consciousness.

Francesco Risso was born on the deck of a boat during a winter storm at sea, and raised in the bosom of an extended, eccentric family of tailors and aesthetes in Genoa. He was not destined for ordinariness, and his stewardship of the Italian label Marni, itself a repository of the unpredictable and the arcane in its 25-year existence, has provided Risso with a platform to explore the outer limits of his consciousness and his creativity. It made perfect sense that I found him in the middle of the Balinese jungle, where he was on a silent qigong retreat for two weeks. I hated to break the silence with a phone call, but System’s needs must. He reassured me: ‘I am out of my silence – I’m ready to talk.’

Tim Blanks: Is qigong a particularly esoteric discipline?

Francesco Risso: It comes from Chinese medicine and was born out of Taoism and the moment when people were actually trying to go a bit against the government, years and years ago, and then it became a sort of practice. I just discovered that it is used a lot as therapies in the hospitals in China. It’s very much about how the body and mind are related, and it is quite amazing. I have been here for 12 days in the jungle and I haven’t seen anything of Bali at all. I am just surrounded by nature and it is really beautiful.

That’s a curious coincidence. That is really where the last collection was: an interplay between flesh and spirit in the jungle.

You know that between the men’s collection in June and the women’s collection, I started to work with the Miao community in southern China? I kind of had this lateral experience with them and it was very, very illuminating. Somehow, it made me wonder a lot about time, and taking more of it. You know when designers used to go on long holidays and come back radiant and inspired? Through that experience with the Miao, I started asking myself all these questions and that is why I am here.

This sounds like a personal quest.

Actually, it is more about finding other ways to gather inspiration. I have always been quite obsessive about my fashion and literature and movies, almost as if I’ve been driving the collections through my familiarity with certain literary phenomena , while also building up the stories and personalities through that process. I never believed I could stop thinking like, I don’t know, Saint Laurent going to Marrakech for a month and then coming back with this amazing collection. But the Miao project was like experiencing and learning other types of processes and coming up with something else.

It’s easy to see this as a search for enlightenment. You’ve never used fashion terminology to talk about your work. You seem as interested in expanding your mind as you are in expanding your métier – and you push the limits of your métier by pushing the limits of your mind. Like when you talked about psychedelissima at the last show. I think you are touching on something unusual in fashion because with psychedelissima, you can have a very good trip but, obviously, you can also have a very bad one.

Absolutely.

Same thing with the notion of child’s play in your work. Children are innocent, but they can also be cruel. There’s always that dichotomy in what you do.

There are a lot of truths in children, in how they relate to the world. It is quite spontaneous. I guess I am quite into spontaneity of thought.

Do you have to work at that or does it just come naturally?

It’s more like a process of evolution. One idea gathers the other and so on, inspiration after inspiration. There is a path between the ideas. But many times, it comes from other people. The last collection, the Psychedelissima collection, came from the people that I met in Brazil, and my interaction with them. Usually I dive a lot into books or movies, but movies are becoming a bit exclusive. It’s almost like you think of people watching a movie at home rather than sharing an experience. So, lately I have been diving more into music. Particularly, the Tropicália movement in Brazil, a mix of artists who were passionate and full of so much love and creativity, as well as so motivated by politics.

‘When I was young, I was obsessed by horror movies and really dark shit. I was fascinated by extreme romanticism that can somehow turn into tragedy.’

You could see the people you spent time with in Brazil have been struggling for years against regimes that represent the death of nature, creativity and the imagination. I think it was Lawrence [Steele, Risso’s partner in life and at Marni] who brought up the idea of ‘beauty as protest’ after your show. That idea kind of worked its way through the whole season. But obviously you need some force behind it.

There are many versions of beauty. I see beauty when I see somebody turn their head in a particular way; that is my personal interpretation of beauty. It is very subjective. But there is also absolute beauty in nature and beauty in the body — that is undeniable. So it’s about playing between the two: the personal and the undeniable. I love that.

You had a past connection with Alexander McQueen and the dichotomy that fuelled him was beauty and horror; yours is innocence and corruption. In your last show notes, you mentioned ‘the fine line between beautiful vertigo and what the fuck is happening’.

It’s not even something that you can define so much, but a few days ago, I was thinking that I like to destroy things and to rip them apart. That made me dig deep, and I thought, ‘What is this? Am I a destructive person?’ So when I dig into it, there is something about detaching from the things you are creating, detaching from the creative act itself, where you are not just this thing you have learned, you can go beyond it to find the pure essence of it. It’s almost like you play with those beauty references, but then you have to destroy them so you can see the essence better. It is a part of my daily processes, a bit like a mantra. Even when I wake up and I have to put on some clothes, I never like the way they are and sometimes I rip them off. It’s not just taking away, it’s detaching. Am I explaining it well?

You are. You get the violence. For me what you do is like Dada much of the time. The only way you get people to look at things differently is by destroying the things they are looking at. How important is the dark side to you?

It’s as important as the light side, I guess. There’s a lot of romanticism in the dark side. When I was young, I was obsessed by horror movies and really dark shit; people were a bit concerned. But actually, I was very fascinated by the extreme romanticism, that extreme love and beauty that somehow turns into a tragedy. I was not into torture porn or anything like that – I was passionate about Nosferatu, Dracula, the Gothicism behind those dark stories.

You call yourself @asliceofbambi on Instagram. Bambi is a horror movie for little kids.

Oh, totally. But such a beauty as well.

Yes, it’s like whenever human beings try to work nature out, they always get drawn into its rawness. That is what I feel in your work, in the Matisse jungle of the last collection and the one that came after you saw the Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud paintings in the All Too Human exhibition at the Tate in London. The way you used colour in that collection, putting it on by hand so that the paint was almost like flesh, that was so incredibly primal.

That was a beautiful process for that collection, and I really treasured those moments, working with the team and everyone in the studio. At a certain point we all sat down and said, ‘We have to make this with our hands.’ All those gestures of pulling up the fabric and moulding it onto the body and also making it quite spontaneous and not too finished. It was underlining the process of the studio and exalting each hand somehow.

That’s very against the whole mechanical aspect of fashion. We have entered an era where fashion is like a machine, but there is a spirit of defiance in what you do, even in the way you talk about your collections, very deliberately in quite abstract or surreal terms. Are you deliberately defiant of the orthodox way of doing things?

There is something interesting in diving into processes that can possibly lead how you make things, as well as resonate in the pieces that you find in stores. For instance, there was nothing haute couture in that collection. It was more about how to drape with your hands to make these pleats and how to stitch them quickly and how to exalt that gesture. Everything was coded, so that it could be shown in that way, but also go into the shops and not just be like falling-apart pieces of clothing. I’m fascinated by exploring the mechanical and unmechanical processes of what we do. It is something that I found so interesting with the Miao people, because it is totally against the core of fast fashion and the speed of our world. It is really like diving into I-don’t-know-how-many-year ago and I find it a fascinating challenge to somehow preserve those values rather than speed. I am a son of speed, but it’s so beautiful to find a different reality to preserve as well.

‘When I wake up and have to put clothes on, I never like the way they are and sometimes I rip them off. It’s not just taking away, it’s detaching.’

Do you think it is possible?

Totally, absolutely. I mean with the trends and the power and money that goes around in fashion nowadays, why not? It would be crazy if we weren’t aware of those things. I mean, are we just becoming monsters digesting everything like obsessed vacuum cleaners? I don’t think so. Most people I know understand time and speed, but also appreciate the value of things and the objects they can treasure in their wardrobes. It’s all possible in that sense.

Instead of ‘why?’, you ask ‘why not?’ — and to me that is the critical question in fashion. Rei Kawakubo asks it a lot. It’s interesting because the sense of human possibility is becoming more and more acute as the sense of automated possibilities gets stronger with AI and so on. It’s all a bit scary, but I believe there is a renewed, positive emphasis on what humans are capable of.

Look at these young children marching on the streets; it gives me goosebumps. My God, it is so inspiring. Maybe we’re on the edge of extinction, but on the other hand, there is this incredible force of young people. It’s probably never happened before that we know. And now we have these incredible minds out on the street doing incredible things. They care about the environment, they are really pushing. And this is the ‘why not?’ There is the testimony of something happening out there that is the opposite of just straight consumption.

How do you make your world relevant to them?

I’m not sure. Maybe it’s not. I want to reach them; I don’t pretend they want to reach me. I’m so fucking curious. If you are outside looking in, they are so inspiring. You look at the young people in the streets protesting and they are so cool, so individual, so beautiful.

What is so powerful is the sense that they have nothing to lose because they have everything to lose. You say that maybe what you do can’t be relevant to them, but what you do, more than most people in the industry, is work to create something communal, something handmade. Everything about that last show, from the clothes and the set to the models with the mud in their hair, felt like a ritual, a pagan celebration.

It is funny because the beautiful side of that ritual is that it was multiple hands merging in one process, in that show, in those clothes. It was all the people that I work with, a dance of multiple hands circulating around one idea.

We were talking about beauty and horror, but that is the world we live in: the hand creates and the hand destroys. It becomes this perfect metaphor for humanity. There is a huge amount of philosophy in what you do. Do you believe in destiny?

I do. There is destiny and synchronizing, I guess. Thank God I don’t remember being born on a boat on a cold day in December. I do remember moments afterwards with my dad and adventurous times when I was surrounded by characters. I think that experience sets a certain DNA that synchronizes with the other experiences in my life.

Being born on a boat during a storm, in air and water, made you some kind of fabulous fairy child. Did you feel special or different when you were young?

No. I grew up in a family with many brothers and sisters and, like any family I know, my siblings were good at making me feel not special. I was the last one, so they were like, ‘Oh, he is the luckiest.’ I grew up with this judgemental vibe and was silent until I was 16 when I was like, ‘Bye, I’m off to have my own experience!’ Maybe that is where being born on a boat came back to me, because I was able to leave. But no, I don’t relate my childhood to feeling special.

How could your quest to find the relevance in irrelevance apply to fashion?

It’s a really interesting question. I had a look around fashion this season and more than ever it felt like everything was the opposite of everything else. What is relevant? What is irrelevant? Do you know?

Relevance to me has everything to do with engagement, urgency, accountability, compassion.

For me, it’s connections. When everything in the world seems designed to divide us, anything that brings us back together is powerful. This is what Greta Thunberg and these young kids are doing now.

Looking at all that is going on in your work makes me wonder if fashion is enough for you to communicate everything you have inside you…

Maybe not. But really, is fashion enough for anybody at the moment?

Models: Dara Allen, Marcus Cuffie, Cruz Valdez, Fernando Cerezo, Stevie Triano, Peter Goldberg, Marcs Goldberg, Devan Diaz, Miles Raymer, Iris Diane Palma, Nico Negron, Martine Gutierrez

Special thanks for Francesco Risso’s self-portrait: Andy Massaccesi