Ibrahim Kamara uses the language of fashion to challenge every kind of stereotype.

By Rana Toofanian

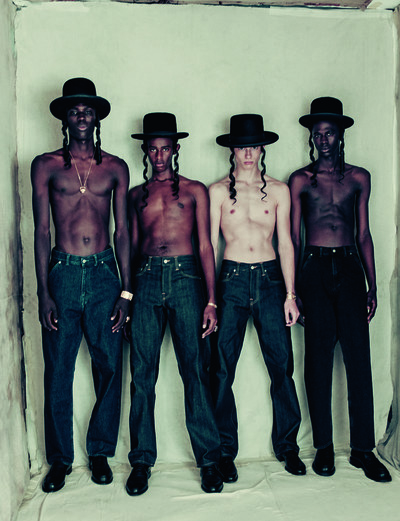

Photographs by Paolo Roversi

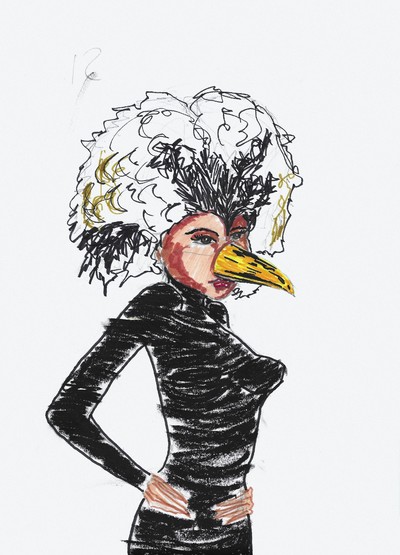

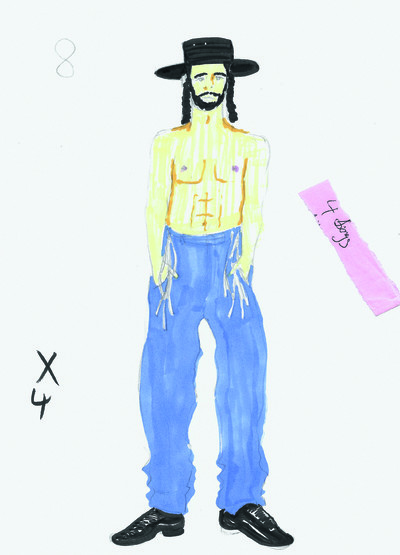

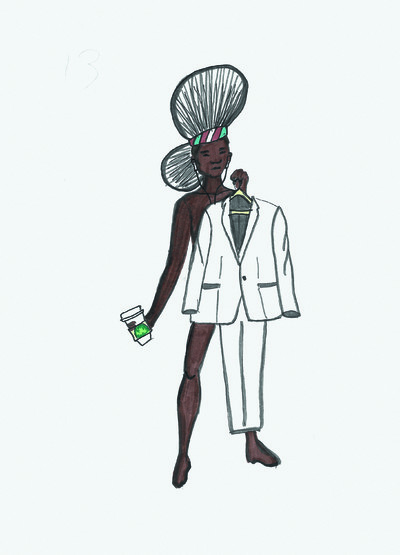

Styling and illustrations by Ibrahim Kamara

Ibrahim Kamara uses the language of fashion to challenge every kind of stereotype.

‘In my world, there are no total looks,’ says Ibrahim Kamara of his unconventional approach to styling. After all, you’re just as likely to find a hat handmade in his bedroom as the statement piece in a fashion image, as you are anything with a designer label. In a remarkably short space of time – he only graduated in 2016 – the 29-year-old, Sierra Leone-born, London-raised visionary has fashioned a space all of his own: one where the policing of masculinity, the rich cultural variety of the African diaspora, and the erotic collide with fierce power.

A born storyteller, Kamara grew up without access to TV or the Internet; the catalyst, perhaps, for the folkloric, fantastical world-building that has now become his signature. Working as an assistant to legendary stylists Barry Kamen and Judy Blame while studying fashion communications and promotion at Central Saint Martins, Kamara has reconfigured the eclectic, knockabout spirit of the celebrated 1980s Buffalo movement for the present day, using its DIY approach to carve a thrillingly new – and implicitly political – take on the relationship between fashion and identity. A regular contributor to British Vogue, Vogue Italia and M, le magazine du Monde, in July, Kamara was appointed senior fashion editor at large at i-D, the magazine where his heroes also learned their trade.

Slipping in and out of his alter egos with chameleonic ease – from the ‘sensitive thug’ character he adopted in his early days to his latest double, Sinegal – Kamara uses the language of fashion to challenge stereotypes of all sorts, but most importantly to create a brave new world where his sensuality, and sexuality, can roam free. Or, in his own words: ‘I think reality is what we make of it,’ he says. ‘I live in my own little world, 24 hours of the day, and I love that world.’

Rana Toofanian: You were born in Sierra Leone and came to the UK by way of the Gambia aged 16. Tell me about your upbringing.

Ibrahim Kamara: I had a very happy upbringing. Back in Sierra Leone, we were living in nature; our home was next to the sea. We were a very big family. I grew up with my step-grandmother and my aunties and uncles. My mum had already left for England in 1994 with my younger sister. We didn’t have a TV, so as children we just played outside and in the streets until 11 or 12 at night. The Gambia had the same energy. We didn’t have access to many things, so we would use our imaginations to create characters and run around the little town. I loved my childhood in Africa – some of my best memories are from growing up there.

It must have been difficult to leave that all behind.

The transition was very hard. All of a sudden, at the age of 16, I had to leave all my friends and move to England. My mother had already been in London for 15 years, and in all that time apart, I hadn’t seen her. The school system here was completely different. I was thrown straight into a college with these really intense kids who were smoking and cursing and talking back to the teachers. It was all very weird. I was very lonely at that time, and I watched a lot of MTV, which really improved my knowledge of pop culture. I hadn’t grow up with the Internet or TV, so I hadn’t been exposed to all that. I had actually lived day to day until then, just talking with my siblings and family.

Do you think that limited access nurtured your imagination and creativity?

Absolutely. When you put kids in a room and they don’t have access to TV or the Internet, they are forced to use their imagination. My friends and I would make up all these little games and characters, and our uncles and aunts would tell us stories. I don’t think I have ever grown out of that mindset. I still see the world as a child and I think that really helps. I have to achieve a vision by any means. If something is not available, then I have to make it. A child would think like that.

What were your earliest interactions with fashion?

Even though my father is the imam of a mosque, I grew up Christian because my mother was Christian. I remember at the age of six or seven, going to have our church clothes made. The tailor

would ask us what we wanted to wear and we chose our own fabrics. It was very personal, but I didn’t look at it as fashion. Growing up in the 1990s, my aunties were influenced by Jamaican and Afro American culture. I would see how they were dressed when they went clubbing, and I wanted to grow up so badly to look and be like them. I was only six years old at that time, but I thought they had incredible style; I still do. They didn’t have fashion, but they had style.

‘Back in Sierra Leone, I didn’t grow up with TV or the Internet. I actually lived day to day, just talking with my siblings and family.’

You began studying medicine before dropping out to attend Central Saint Martins…

I was three years into my studies, and I don’t remember exactly what happened, but I just lost interest. I made a deal with my mother to take a year out to find myself. I came across Live, which was a youth magazine run out of Brixton. One day I stumbled onto a set where an editor was styling an old man, and I just thought what she was doing was cool. After my year was up, I had to break it to my mum that I wasn’t going to go back to studying medicine. That was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done – confessing to an African woman that I was not going to become a doctor. She was heartbroken. She had all these dreams of what her son should be, her ideas of what success should look like, and I said no to all of that. That is how I fell into the world of fashion. I didn’t know anything back then, but I was intrigued and had an intuition that it was something I wanted to explore.

How was your experience at Central Saint Martins?

It was life-changing. Before I got into Central Saint Martins, I went back to college and did a two-year degree in art and design at Westminster Kingsway. At CSM, I realized that I loathed everything I had been doing before; it wasn’t cool anymore, and now I just wanted to be cool. No one there wanted to work for the big magazines. They all rejected that kind of establishment. They were rebels. I was still living at home with my African mother, who noticed all of these changes in me. I used to look like every other kid on the block, in tracksuits and jeans. Then, all of a sudden, I was wearing tights and boots and had my ears pierced. I started going clubbing, too. I wanted to look like the people there, the kids in my class, my peers; I wanted to wear lingerie and a bomber jacket to school because that’s what everyone else was doing. I would hide my clothes in my bag when I left home, change and run to the bus. It was all a rush. The only world that mattered to me was Saint Martins. You change every year you are there, and by the time you are in your fourth year, you are transformed. It wasn’t just what I wore or the things I looked at either. My take on religion also completely changed. I used to go to church every Sunday and then I became an atheist. I looked at the world differently, in a more loving way. I became more confident in my sexuality; I had gay and trans friends. There was no judgement anymore. I am so comfortable in my own skin due to my experiences there. I went in there thinking I had this very specific idea of what I wanted to be and came out realizing that I can be whoever I want.

You assisted Barry Kamen while you were there and you’ve previously described him as having been a mentor. How did that relationship inform your approach to fashion and styling?

I came across Barry’s work with Neneh Cherry, and remember thinking, ‘If I were to be a stylist, that’s how I would style.’ This was during my time at Saint Martins when we were all really fucked up in the head and wanted to tear things apart. It wasn’t even about being cool anymore, it was all about being new. I e-mailed him my work and he responded explaining that he wasn’t styling much any more, but thought I was exciting and loved my stuff. The following week, we had a coffee at his office. We didn’t talk about fashion at all; we talked about everything else on the planet, except for fashion. We connected about politics and culture. For me, he was always ahead of his time, in the way he thought and the way he styled. The story he wanted to tell was always bigger and more important than the clothes or the collections. Barry always really encouraged me to do my own thing. He created an environment where there was no right or wrong to my thinking, where everything was accepted. His studio was always open to me and I had access to all his stuff. Barry became more like a father figure to me. We were always talking, laughing and coming up with the craziest ideas, like two little boys. We were both so excited by each other. When he passed away, I was really hurt. I lost my best friend and my mentor at the same time. After that, I didn’t know who else to work for aside from Judy [Blame], because Judy made stuff.

‘I used to look like every other kid, in a tracksuit and jeans. Then, once I got to Saint Martins, I was wearing tights and boots and had my ears pierced.’

Barry was the poster boy for the Buffalo scene. The eclectic references, multicultural representation and transgressive masculinity of your work evoke a similar spirit. How did Buffalo shape your own creative outlook?

When Barry gave me the Buffalo book, I started looking at Ray Petri’s work and attempting to study it. But I don’t think you can learn Buffalo. You can only experience the spirit of it, and that is what Barry instilled in me. To me, Buffalo means having a hunger and thirst for culture, to be fearless, to go to the end of the world to create new narratives. That is what Barry always pushed me to do. Buffalo is very stylish, but there’s a lot of thinking behind it, like putting Pakistani boys in suits with English flags wrapped around their waists. That is quite brave, that is saying something that goes beyond styling.

It’s cultural provocation, but in the most tasteful way.

In 2016, you and photographer Jamie Morgan collaborated on an editorial for Dazed titled ‘The Other Paris, Rue de Regard’, an ode to Barry, who had passed away a year earlier. In it, young Franco-African men you had street-cast from gay clubs, subways and strip clubs near Château Rouge were

captured in a poignant but liberating fusion of fake luxury goods, sportswear, bridal gowns and heels. One of the story’s most striking images pictures a seemingly pregnant young man wearing jeans and a headwrap. Tell me about the concept behind the shoot and why it felt like a fitting tribute…

It was my first editorial for Dazed. After Barry passed away, I was at a very traumatic point in my life. Those were some of the ideas I wanted to explore that I had discussed with him and that we would laugh about. He thought I was so brave to be talking about pregnant black boys. It was funny to him. The African community in France experiences so much discrimination. They are not as visible or as integrated as we are in the UK. London is such a multicultural city, but when I am in Paris, it is so divided. I wanted to highlight the beauty of these everyday people, of African immigrants, and what they bring to Paris. It would have been easier for us to photograph a pregnant girl, but for me, that isn’t exciting. A boy in jeans is so relatable, and by the time you turn him pregnant and put him in a headwrap, you are saying a lot. He is born as part of a generation of young, black African men in France experiencing the struggles of discrimination. It hurts my feelings because some of these people have degrees; they are doctors back home. They come to the West in the hope of a better life, but instead they are shut out. We also photographed a boy in a wedding dress. For me, that is punk. An African man taking a walk in Paris in a wedding dress, irrespective of all the things he has to face, that is as punk as it gets. It’s a total fuck you. There were all of these subtle political messages and ideas in the photographs – enough to make people aware but not scare them away, so that they could still come to their own conclusions of what the images were trying to say.

When that story was published you said you hoped that it would change something. Do you think that fashion imagery has the power to affect real change?

It goes back to my past, to growing up in Sierra Leone. It was very political. Being at home, listening to the news, hearing all these very intellectual, politically driven conversations about the world. It was constant news, and the news was where I also consumed pictures and advertising. I am mostly drawn to things that have a narrative. When I create pictures, I develop written narratives and backgrounds for all the characters and think about what each character is saying in a frame. I genuinely hope that my photos spark something in people’s hearts, that they are not just a thing you flick past and put

away. I hope that people want to stop and analyse them, that it inspires young kids and older people alike to seek out my references or to try to understand and relate to my work.

Africa is obviously an important theme and source of inspiration. In what ways do you feel your past is represented in the work you produce and ideas you cultivate?

I see the world through my past experiences and how I can project them into a new space. My youth in Sierra Leone is always my first point of reference. There was something exciting about growing up in Africa. There were no fashion magazines telling you what to wear. You just make it up as you go along, which I think is so stylish. The most stylish people live in parts of the world where there is no one telling them what is hot or trendy. Sierra Leone is a colourful place – the woods, the beach, the way people carry things on their head, product placements in an African market – the way they know nothing about how the modern world thinks of marketing, but they can sell you anything. All those elements are reflected in my work and are things I review when I’m writing a story or sketching ideas. When I go back to Africa, I see kids there now who have access to the Internet taking inspiration from China and Europe, and combining it with what they already know. There are new subcultures coming out of it: new ways to dress, new music, new pictures. I find all this newness so exciting.

‘A boy in jeans in Paris is so relatable, but by the time you turn him pregnant and put him in a headwrap, you are saying a lot.’

You frequently use the word ‘new’. Why do you think you are so drawn to novelty?

I am compelled by progress in culture, especially when people take ordinary, everyday items and turn them into something new. Because I am from that part of the world, I can relate to people striving to create something that is new or hasn’t been seen before, especially because the Western world has long been what is considered cool, edgy and new in fine art, music, and fashion. In Lagos, the kids who are skateboarding don’t skate the way they do in America. It is punk; it is fresh and new. They take elements of what they see of skate culture and absorb it into their own culture to create something different. That is what I strive for with every story I do. I want to bring new things into the world. I am always summoning new ideas; I will wake up in the morning and start the day by writing. I am the worst person to watch a movie with because I screenshot every scene. Each one is an idea and for me, it’s about how I mash them up with my own experiences. I never want my last story to reflect my new one; there might be elements but they must be developed. I reference the past but without holding on to it.

How do these stories materialize from conception to creation?

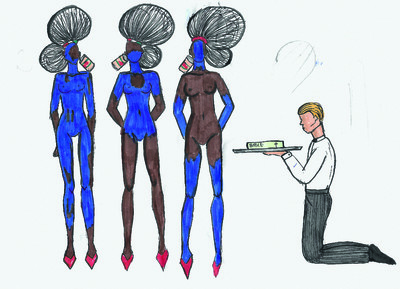

First of all, there is a lot of writing involved. I watch movies and I write about the characters, but I don’t see the styling in my head at all. Then I decide what I’m trying to convey, which allows me to see if I need to build stuff. In that case, me and my team – Sasha and Joseph, and my friend [designer] Gareth Wrighton on certain projects – all experiment together and then sketch everything in-house to see if it all looks right. After that we look at colours and then I start looking at the collections to see if they align with what I want to say. Fittings are usually over the course of two days and we match the clothes with what was sketched on paper. I like to know exactly what I’m going to do on set, so if we change something it won’t be too drastic. Barry used to do all the fittings on me, so if we were going to do 20 styles, he would style everything on me. He had immaculate attention to detail, so I try to take that with me.

You mentioned movies. Do you have a favourite?

I think my favourite is August: Osage County with Meryl Streep, which is about a woman with cancer and the way in which her family has to come together and take care of her. It is about human forgiveness and love. I definitely need to do an editorial on that. Another highlight would be Cloud Atlas, which is so full of meaning, and Apocalypto, which has some really great costumes.

Someone once described your work as future-leaning and utopian, while also paying homage to stylists of the past. Is this a fair and accurate observation?

It pays homage to the spirit of some of the people before me who I think are incredible and who all brought something new into culture – Barry Kamen, Ray Petri, Judy Blame, Panos Yiapanis. I love the American Vogues of the 1960s and 1970s, that era when things were so imaginative, where they travelled and told stories so the viewer could really dream. That is how I want my work to be. I want it to be like an advertisement. The reason brands pay for ads and placements is for people to look at them. If they don’t stop to look at them, then they have failed their purpose. I want you to flick through a magazine and look twice at something I’ve created, and try to analyse what I am saying.

To me, that is what advertising is supposed to do. Even if you don’t want to buy the dress, it stays as a memory deep inside your brain.

Panos once talked about his feelings of frustration as a stylist in relation to the ownership of images. He said that it was always about either the designer or the photographer, and that as a stylist he often felt like he was floating some- where in between, as a ‘perennial gypsy’. Do you ever feel like that?

I have recently because I really invest a lot of my heart and soul into every story that I make. I don’t think that it is fair that a photographer is the only one who owns the picture. I think that is so outdated. I am not just a stylist. I use my imagination. I build characters. I research as much as the photographer does. It takes time to put things together. Before we shoot, we do many fittings, many ideas are explored and trialled. I think very carefully about how it is going to look on camera before we shoot. Usually, I have invested my own money into it and actually made the costumes. To go through all that hard work, and then have someone else make an executive decision to turn a colour photograph into a black-and-white one just because they love the aesthetic, is very disheartening to me. It kills the culture of the image, the character is dead, and it is no longer what it was supposed to

be. A photo is not made by one person. There are some mornings when I wake and think, ‘I am going to take the photos myself because I am really fed up.’ I think that might drive me to want to direct films eventually. I write a lot, I have written two things I want to direct, so I think I will do that, and maybe that is where my characters will fully come to light.

‘Buffalo was stylish, but there’s a lot of thinking behind it, like putting Pakistani boys in suits with English flags wrapped around their waists.’

There is a growing trend for designers to enforce strict terms on how their looks are shown in editorials, like insisting that full runway looks are not mixed with pieces from other designers. How do you feel about that?

It is a shame that we are heading down a path where everything has to look the same. Imposing another stylist’s vision on me is really problematic, especially with editorials. In my world, there are

no full looks. I create my characters. I get where the brands are coming from and that they want to maintain their identity, but the people who consume the brands don’t want the full look. You are telling the ordinary person how to dress and that is not how humans think; they take things and put them together. It’s unfair that this is now so strictly imposed on stylists, especially my generation of stylists who are now breaking through. It will kill creativity. Isn’t it more exciting to see the clothes that you have designed in another totally different way? If there is no self-expression, it becomes advertising. It is no longer styling.

Has your method of dissecting, distorting and recontextualizing ideas for editorial narratives ever been a hindrance or restricted with whom you’ve been able to collaborate?

I am sure there are people who don’t want to work with me because of my process. When I request things, they sometimes ask, ‘Is this going to be shot in full? Who is going to wear it?’ Such questions are irrelevant to me and the way I see the world. The person I am going to put in that dress has a richer history than the dress itself. Take the dress away and they remain the person they have always been. I don’t think I will ever do a photo with a full look. In my mind, that would be copying another stylist’s work and that would go against everything I stand for and believe in.

One reason we’re sitting here today is 2026, a captivating collaborative project you produced with South African photographer Kristin-Lee Moolman while you were still a student at Central Saint Martins. The images in that series present a utopian vision of African men in a future time and place where race and gender don’t have the same meaning as they do now. I’ve read that you first connected with Moolman through Instagram, and only met her in person once you’d flown to Johannesburg for the story. How did you work together to achieve your vision?

Before Barry passed away, I talked to him about wanting to travel. He encouraged me to go and said there was nothing more freeing than being in another land creating, unaffected by what is going on at home. That was what 2026 was really about. I bought my ticket using my student loan, got on a plane and went. I had wanted to work with Kristin because I loved the way that she photographs the new African experience. I chose Johannesburg because I felt that it was the most progressive African city at the time. I knew it was going to be way more impactful to photograph those ideas on the streets of Africa, a place the world thinks of as dangerous, than in a studio in London. Even though I had done a lot of research, the end result was surprising. Kristin and I immersed ourselves in the project for a month. We rarely had access to the Internet and I hardly spoke to my friends back home. Having no outside influences meant we could push our ideas further. I was clubbing in Johannesburg. The youth there were so radical, the artists and musicians were breaking away from tradition to do their own thing. It was like London, but new. It was the perfect environment for experimenting with ideas. All the boys and girls we photographed as part of the project were incredible people who I felt had a different mindset; they had abandoned their parents’ way of looking at the world. They could really connect with the work and stories we were trying to tell. That is why it felt so personal in the end.

‘We sketch everything in-house. After that we look at colours and then I start looking at the collections to see if they align with what I want to say.’

Who were the people in the photographs and how did you find them?

Some were Kristin’s friends, some we met in the clubs and on the street. We put every photograph we made on a wall, and within two weeks it was full of pictures. When we found someone, we would bring them into the room to show them and explain, ‘This is the world we are building’, and 99% of the time they would say, ‘I want to be part of that world.’ We were cutting and making pieces, diving into dumpsters, sometimes we would pack stuff in the car and just get people off the street and style them there. It was a very experimental process. For the first time, I saw more of myself in the work I was doing. In a way, 2026 was really my coming-out story because those were the boys I wanted to look like in my head, but I was never brave enough. I was never bold enough to stand on the street wearing one shoe and different socks and a skirt and headpiece and an earring with no fucks to give. I really found myself on that trip and I came out to my family afterwards. I could not have done that

without 2026.

I’d like to discuss Soft Criminal, the second show you worked on with Kristin, which was your first large-scale exhibition. Was that project an extension of 2026 or a separate entity?

Soft Criminal was born out of 2026. After the initial idea came to me, I asked Gareth Wrighton to join me and Kristin in creating the story. I’m not a trained designer and I knew that if ever I was going to make clothing then I would need Gareth’s eye. We chose a name early on, I pitched ‘soft criminal’ and it just stuck. Then we created a family of people – from kings to the queen and the agents – who were fighting for power to reflect what is going on in the world right now.

What does it mean to be a soft criminal?

During my second year at Central Saint Martins, I started to realize that I am an individual, even though I am a black man and the world might see me as a hardcore person. I have feelings; I am just as soft and vulnerable as any other man. I wanted to reflect that in my work, so I set up a Tumblr called Sensitive Thug. Soft criminals and sensitive thugs are people who are very hardcore – killing each other while fighting for power – but once you put your fears and insecurities about them aside, you may also start to glimpse their tenderness and humanity.

The subversion of stereotypes – specifically those related to masculinity and sexuality – have become recurring themes in your work. Why?

For a long time, I didn’t know much about sexuality. In Africa, two men could hold hands and it was not because they were gay; they were just friends or family. Masculinity is so overemphasized in Western politics and entertainment. I wanted to change the way kids, my friends, and the people who look like me are seen. As black men, we are just as vulnerable as everybody. We all have emotions. We are not all as strong as you think we are. I wanted to highlight those individual identities of blackness and of my upbringing. Humans have a way of prejudging what a person’s experiences are without getting to know the person. I am fascinated with how to fuck that up a bit.

Do you think that creating an idea through a fantasy can alter a person’s perspective of that idea in the real world?

It can soften their perspective. It might never happen in the real world, but seeing it visualized in a photo has the potential to spark change. Imagine a muscular African man holding a briefcase and

going to work in a wedding dress. Whatever you take from this image, it indicates that the person behind the dress is vulnerable and brave and that they have the strength to stand out.

Do you use fantasy as a way of vocalising what you perceive in reality?

Absolutely, my work takes things that are relatable in reality and exaggerates them through fantasy. Also, I feel fulfilled when living in a fantasy – it is more fun than my own reality.

The ‘new Africa’ movement is often associated with your work. What does that phrase mean to you?

It denotes young people of African heritage who haven’t conformed to the stereotypical roles like they are supposed to. They are chaotic, but in the most tasteful and beautiful way. They are really pushing new ideas, the ones our mothers will be petrified of for decades. These kids are not studying to be scientists, doctors, or lawyers. They are going broke for new Africa, disappointing their parents in the most beautiful way. This movement is happening all over the continent and also among Africans in the Western world right now. That rawness and rebellion, that’s what I think new Africa is.

‘Consumers don’t buy full looks. Brands are telling ordinary people how to dress, but that isn’t how humans think; they put different things together.’

The images in 2026 became part of a group show called Utopian Voices, Here & Now. Its curator, Shonagh Marshall, said that it was the ‘perfect example of using clothing to consider how it can construct identity’. Is it possible to use fashion in that way?

Absolutely – in fashion, art and music. For now, fashion is the part I have access to in order to tell my stories. At this stage in my life, I’m still figuring out what I want to say. I’m pushing myself to think more deeply and eventually I think I will find other mediums with which to tell the same narratives, probably more evolved, with more of a broken heart, and with more love and growth. I’m just so excited to explore those new forms.

Describe your own personal aesthetic and how it is affected by your work…

I find it very hard to dress myself, as usually when I put things together I am not happy. I have a basic uniform. My work is better when it’s enhanced on other people. My work reflects my alter ego Sinegal. I think that is the person who is more aligned with what I do. Personally, I am more reserved. I try to keep my ideas for my work.

Sinegal was recently filmed and photographed for Vogue Italia. Who is he?

I am a Gemini and I have always felt that there are two sides to who I am. I’m trying to figure out exactly who Sinegal is, but I experiment my most daring ideas with him. Having an alter ego allows me to go to extremes but somehow still keep myself apart.

In regards to your work, what motivates you right now on a broader level?

Pushing myself to create new narratives and ideas makes me so excited. As does the thought of creating something that has never been done before. All of the people I surround myself with are really ambitious and creative and that motivates me to continue. I get energy from them and they get energy from me – it is collective motivation.

Is there a fashion designer who you particularly admire?

Margiela every season. I am obsessed with John Galliano and everything he does at Margiela because I think that making something so conceptual become commercial is like winning. When you can make the ordinary person want to wear the craziest cut to the office – that is genius. I look forward to seeing the show every season.

You are the newly appointed senior fashion editor at large for i-D. What does this mean to you personally?

i-D is so connected to youth culture. As long as I feel young, I can project culture to the masses through i-D – that was one of the reasons why I agreed to take the job. My goal for now is to travel

the world and tell stories.