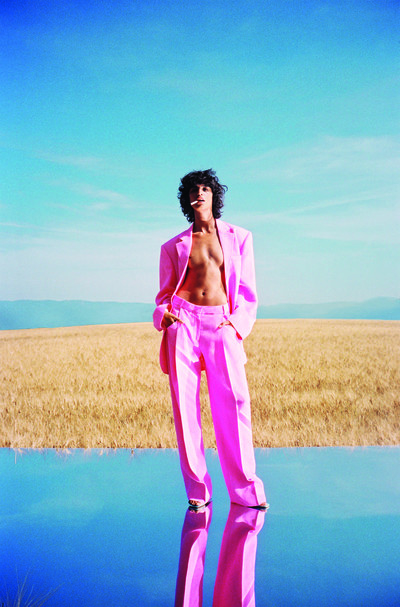

After 10 years in business, and still under 30 years of age, Simon Porte Jacquemus takes a moment to reflect on family, fortune, and the future.

By Loïc Prigent

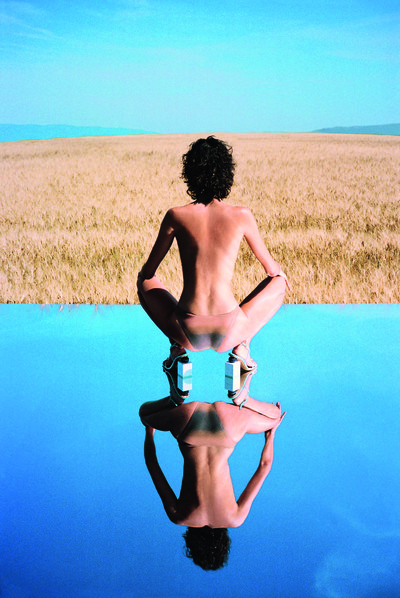

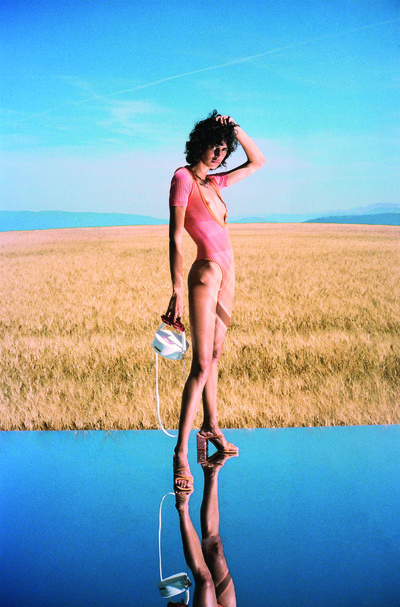

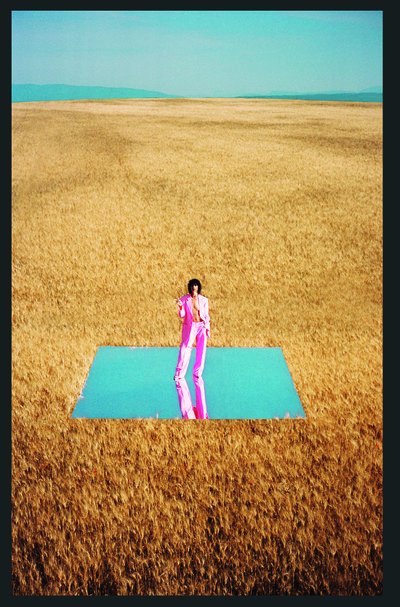

Photographs by Pierre-Ange Carlotti

After 10 years in business, and still under 30 years of age, Simon Porte Jacquemus takes a moment to reflect on family, fortune, and the future.

Back in June, Simon Porte Jacquemus appeared in a lavender field in Provence to take the applause after his 10th-anniversary show, his biggest yet. It marked the end of a decade in which this self-taught designer has built his start-up brand, Jacquemus – the maiden name of this late mother – into a €40-million-a-year business. From the beginning – when instead of fashion school he began his label while working as a sales assistant at Comme des Garçons – to today as a high-growth fashion business with precisely zero bricks-and-mortar stores, Jacquemus has continually followed his instincts. With best-selling, Internet-breaking hats and bags seen on the biggest stars, and easy-to-wear, yet skilfully constructed clothing, the brand has become a unique part of the fashion landscape. Yet after the acclaim for the beauty of that Provençal show – all pink carpet, bright clothes and purple lavender – the designer began to question himself about where he was headed. As his brand turns 10, Jacquemus the designer is approaching 30, and increasingly wondering about the role of fashion today. ‘How,’ he finds himself asking, ‘can we do things better?’

Loïc Prigent: Let’s start with Jacquemus, the brand, and the company. You’re still independent?

Simon Porte Jacquemus: Yes, 100%, by choice. At the beginning I might have needed help – I was 20 and I didn’t know exactly what was going to happen – but my dream was never to be bought out. It was exciting to think that someone might want to buy the company, but I never wanted it to actually happen.

Wouldn’t it have simplified things to have more financial backing?

I don’t think so. I think if it’s happening this way, then it’s happening in an organic way. Of course, it helps having more money, but what you often see is that it slows down creativity. I’m well aware that there are brands with millions of euros in the bank, but they don’t manage to sell their clothes or make a real impression on their clients. It’s not a magic spell. It’s really good that all that could have happened hasn’t happened! It could have finished in a situation where I no longer understood what I was doing and ended up completely disconnected, just doing my clothes on an extraordinary salary. No, I think it’s good that I’m still grounded in reality. Even though extraordinary things are happening, I’m still grounded.

You’ve always been connected with the business side?

Of course! I have advisors who I often see and they have helped me, but that’s only once a month. Everything has happened, in terms of the figures, really organically. I work on instinct and it’s always led me. My strategic and financial advisor always says, ‘Simon, you’re the only person who guesses the figures, the exact figures!’ I always know exactly how much we are going to turn over the next season, and I never get it wrong. I always say what it’s going to be and he’s always surprised when I’m right. I can feel it when things are right. I’m the one who is the most exposed to everyone, and I can just feel it, I don’t know how.

An internal business barometer?

I don’t know. That sounds a bit weird.

If you guess right every time, that’s really crazy.

But the situation has been pretty crazy! From the financial point of view, it’s quite exceptional, the bankers have always said to me, ‘Wow, there have been almost zero loans.’ To get where I am in such a Zen manner, is pretty rare. We’ve gone from €10 million to €20-something million, from €20-something million to €40-something million.

Do these figures give you vertigo? When you get to €40 million?

They’re just figures; they don’t really mean anything to me now. My work is not about the number of zeroes in figures. I don’t give a shit. I’m going to be 30 soon and I’ve been asking myself lots of questions about life, about lots of things. It’s true, it’s beautiful that Jacquemus works; it’s beautiful that we have a clientele; it’s lovely selling more clothes – but we and I can do better than that. That’s more my philosophy now: I want to grow without putting on weight! I said that quite recently and that’s really what I feel. When you start out, you’re in the race and you’re thirsty. I was young, I wanted bigger shows, and so on, but now I’m asking myself other questions and in fact, it’s healthy that I’m asking them.

‘I arrived at Comme des Garçons at 22, wearing a kilt, and with long Kurt Cobain hair. They all said to themselves, ‘What on earth does this one want?’’

What do you mean, ‘I can do better than that’?

All the processes from A to Z, I’d like them to be done better. If we could be more committed on a human level, have a certain philosophy in my business. I’m reading Let My People Go Surfing, the book by Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia, who really created something special, and his point of view is really interesting. I’m trying to think out of the box. I don’t want to be competitive any more; it’s strange. To be perfectly honest, I said to myself recently: ‘It’s been 10 years, the last show was magnificent, our office building is magnificent, your mother would be very proud of you, bravo, the job’s done.’ I called my grandmother, I said, ‘Are you happy? Have I made you happy?’ And she said, ‘Yes, we’re so proud.’ And I said, ‘OK, then it’s time to move to the next step. I want to be the man who does something good and more than that.’ Even if I’m a good boss, I think, I want to do things that make more sense to life today and in the world in which we live. I got back from holidays, and it was pretty instinctive, I said to everyone, ‘What shall we do? Are we really going to do fashion in the world as it is?’ I’m really asking myself big, fundamental questions about why we’re doing this and who it’s for, and how. I’ve changed everything in just a few months. I’ve got a real battle raging in my company, ranging from small things right up to the big ones. And it’s not just a question of ecology – even though ecology is a big part of the changes we’re making – it’s about good practices and a different philosophy, organizing our time better. Everything that fashion doesn’t really let us do. I was happy not to be part of fashion week this season; I’ve really been asking myself lots of questions.

It’s interesting you are asking who you are doing this for. I get the impression that you have always been aware of that.

When I said that, it was really in terms of re-evaluating the idea of overproduction, and creating new trends each season. It’s much deeper, yes. We have a philosophy and something to say, but beyond that, what are we doing that’s good for this world? It’s quite philosophical. I said to myself, ‘OK, let’s take 25 to 50% less fabric this season and see if that forces me to focus on projects that make sense.’ For example, let’s recycle fabrics, send them to Lesage to make new fabrics, work with an atelier in Paris that helps people who are struggling. I don’t know, have projects that make more sense and have real human values. That is more my ambition for the next 10 years. It’s more about that. I don’t care about any dreams of grandeur or bigger runway shows any more. I’ve done my biggest show and it feels fake to be part of this endless race; the idea of ‘more, more, more’ actually disgusts me now.

Disgusts you?

Yes, it’s not healthy.

Did you ever do this for the money?

No. Today I could make more money, but that’s the exact opposite of what I’m doing. I’m not sure that that’s what would make me happy, so I’m asking myself questions. I feel so free today that whatever I decide to do now, I really have to continue feeling absolutely free, otherwise I won’t do it. I’ve always said I’d prefer to shut up shop than give Jacquemus to someone else. That’s not the meaning behind what I do.

Because you did it for your mother?

Yes, I did it for her. It carries my mother’s name, so it’s worth more than the 10 years of work, more than you can imagine. It’s certainly not a question of money. In fact, that’s what is hard when I find myself with the big finance people, it’s hard because we’re not talking the same language.

When you won the LVMH Special Prize in 2015, thanks in part to Karl Lagerfeld and Bernard Arnault, did they give you a mentorship?

Yes, for a year.

And how was that, did you learn anything?

It made me grow up and it really was a help. There weren’t many areas where I needed help because my management and communications were already good, and I knew I had to sell one collection to pay for the next. There were certain things that I struggled with, though, and it really helped me to become an adult and to look at things from all sides, particularly sales and the legal aspects. That prize really helped give me a healthy foundation. Though I feel like it was 30 years ago when I talk about it. It is very odd for me. The last two or three years have been so intense that when I think about the past, it feels so different.

‘I don’t care about any dreams of grandeur. It feels fake to be part of this endless race; the idea of ‘more, more, more’ actually disgusts me now.’

Have there been people you admire in fashion from a business point of view?

Of course, I admire Rei Kawakubo for her business, which is quite particular, for her boutiques and the way she sees things. Her idea that anybody can buy something when they go into a Kawakubo boutique is quite amazing, from Converse sneakers to a couture dress or a suit for a man to wear to the bank. It think it’s a genius brand, as a business, as a way of being different; it fascinates me.

You saw Rei Kawakubo’s business up close?

Yes, and it reassured me about being radical and thinking that it could work if I wanted to do things differently, that it could be more understood in a way.

What did you do for her?

I was a sales assistant in Paris, and I helped do the window displays. I also did an installation in the showroom because I had an eye, but it wasn’t a new position; I was still a sales assistant.

How old were you when you were working for her?

From 22 to 24, I think.

In parallel to Jacquemus then?

Yes, I would design and the day after I would be back selling at the boutique. It was a nightmare, horrible, really hard, but then it taught me to be simple in a way. In the evening, you open fashion week and you get the impression of being the eighth wonder of the world, and then the next day, you go back to work, to serving people, which I loved doing, by the way. I love selling; it’s a passion of mine. I would have nightmares before arriving at the boutique. Then after I had left Comme des Garçons, I continued having nightmares where I’d see Adrian calling me, saying, ‘Simon, you have to come and help me quick, I’m in the shop and there are so many people.’

[President of Comme des Garçons] Adrian Joffe?

Yes, we saw each other often; we would talk about everything. We were close, but less so recently. Perhaps I’ve needed him less in a way. It’s been natural; it’s not a problem. I know I can count on him if I need him; he’s always there to listen to me. I think he understood the brand wasn’t a joke. Being close to him, he would test me to see if I was committed to my label. Quite often he’d say to me, ‘You’d give all this up if a big house came calling…’ And I’d say, ‘That would be dreadful – not at all!’ And he would be like, ‘Good!’ He wanted to see who I was, because I was young. Just imagine, I arrived at Comme des Garçons at 22, wearing a kilt, with long hair like Kurt Cobain and they said to themselves, ‘What does this one want?’

How did you get that job?

By forcing my way in. I needed a job and was contacting all the design studios, but I didn’t have a degree or anything, so no one ever answered. But they did get back to me and I met Adrian Joffe, and it went well, but he said I was too much of an artist and he couldn’t see me working in a boutique. I called him back and said, ‘I don’t agree with your answer. Please give me the job. I’m going to get up early every morning to do my collection and I’ll be the most motivated of your salespeople.’ I was crazy; I did things wholeheartedly.

What exactly do you mean when you say you love selling?

It’s exciting. I’ve always liked the commercial vibe at the market with my grandparents on a Saturday or during the summer holidays, selling things. At Comme des Garçons, it is a particular clientele and it was always challenging to sell. I loved making them think that they didn’t want to buy anything, because that was when they bought stuff. With certain actresses, they’d be like, ‘Oh, I don’t know, Simon’, and I would say, ‘No, don’t buy it, if you’re not sure; you do really have to want it because it’s such a beautiful piece’, and they’d say, ‘Stop! But it’ll be sold’, and I’d say, ‘Yes, for sure.’ ‘OK then, I’ll take it!’ It was like play-acting.

And still today, you’re pretty good at selling? With your social media, everything is very direct, you just put the clothes against a white backdrop. Without…

…any chichi, yes. People like to see the product and I think it works really well when we just put the product like that. I have a clientele that really follows me for my products, I’m not going to deny that, so when I put the products up, it works.

One of the brand’s real strengths is its accessories. Did you anticipate becoming a brand known for this? It wasn’t immediate. The Chiquito bag took quite a while to appear…

Yes, that’s true; it was La Bomba collection [in September 2017].

‘I’m well aware that there are brands with millions of euros in the bank, but they don’t make a real impression on their clients. It’s not a magic spell.’

There weren’t any bags before that?

No, there were a few, but they were less visible. There was a red ball bag in a net, like a basketball, another one that was bean shaped. There were the shoes with a circle and square, which we still sell.

Those were your first hit accessories?

Yes. Selling bags doesn’t strike me as that crazy, though.

It feels like it was a catalyst. When people could see the accessories everywhere, then they realized that the brand was real.

Yes, that and the hats. They were the biggest phenomenon, and got us on the covers of all the Vogues and so on, after the Santons de Provence collection – they were a real phenomenon. My summer collections always drive success. Winter we almost stagnate, but summer we double.

The 10th-anniversary show in Valensole was a summer show, too. How do you explain that? Is it geographic?

It’s another difference, from what I hear. Most other designers are much more at ease with winter. It’s easier, it’s more covered, so the pieces can be more complicated. There’s less skin. But I think what people like about me is a certain sensuality. That is what triggered it. When the Jacquemus woman really became a woman and sensual, it ticked a few boxes in fashion that were missing. Something light, something sensual, without being vulgar.

It was like you just relaxed with that change. Because the earlier shows had had more deconstructive effects; they’d been more cerebral and felt almost Comme des Garçons-esque.

Of course, you can really see the influence of Comme des Garçons in my work. Comme des Garçons was like my school; I’ve always said it. I learned so much, not only the philosophy, but also the garments. I spent my days trying on clothes and looking at where the sleeve came out of the back, where the stitches were. It really was my school; I make no bones about that – there was a very real

influence from Comme des Garçons on my work. In the shirts, in the way I cut clothes, you can see also some Margiela in that sort of conceptualism, but there is a lot of Comme.

The Santons de Provence collection [Spring/Summer 2017] was simpler. Is that because you didn’t have time to finish it as you wanted?

No, no. There was a collection just before that called La Reconstruction that I don’t really remember. It was like bits of clothing; I think I wasn’t sure who I wanted to be at that moment. It was like there was a bomb in a bin full of clothes and that was what came out; everything was broken up and all weird.

Did you want to annoy the people who were there?

I don’t know what it was. There was just something happening in fashion then, and I wanted to do my own bit of chaos. It was maybe a bit dangerous, but I had so much fun.

But you alienated people with that show. That was a risk.

I didn’t get that impression; it was what it was. Then the following summer I really wanted to go back to who I was, what I liked; I wanted to do something that was 100% me, very pure. So I said to myself, I’m going to make santon toy figures like my grandmothers’, like the ones in nativity scenes from my childhood. The project was a bit odd, frankly. On the boards, it really didn’t look like much. You had all these santon figures from the nativity scene and they didn’t make you want them. It was a bet. Who’d have thought Rihanna and all the others would have worn those hats? We didn’t think about that at the time.

At first glance, it was a bad idea?

It was a typically French bad idea. I should have done something feminine and modern. It was pretty major at the beginning because I was completely single-minded about the Santons. I looked at the images yesterday of the first fittings and they were superb. It was weird, very dramatic. It’s still my favourite collection.

The Santons marked the end of the conceptual period?

Not an end, but the beginning of femininity. The beginning of something elegant, the collection that came after was quite dark, then came La Bomba, and yes, I think I was liberated then. I gave myself the chance to be the woman I have inside me, who is from the south, who can appear a bit ‘slutty’, not ‘slutty’, that’s not the word, but can seem a bit too sensual.

‘I have taken all Jacquemus deliveries in-house. Everything is sent from barns belonging to my grandparents and run by a large part of my family.’

That sensual woman was already there in the Parapluies de Marseille and La Piscine?

Yes, but it was the sensuality of a young woman who wears her father’s big T-shirts, very beautiful, but with something naive about her. She was really Éric Rohmer.

She’d French kiss, but not sleep with you.

Yes, that’s it, she was still 17.

But then with La Bomba, she’d definitely have sex.

Oh yes, she was on fire!

Did you have this very precise idea of constructing the brand in your mind, or was it through conversations with other people in your team?

I have tried to create quite strong images of Jacquemus from the beginning, with cars, furniture, and films. My inspirations for what I want to put out there in fashion have always been there, right from the beginning. In fact, there were aesthetic shocks, like Godard and the credits of Le Mépris, which really marked me and gave me the desire to create my own world. If you look at the foundations of what I love, everything is linked still today. It all makes sense because it’s always me who is deciding, 100%. It’s me who says I want pink carpet when everyone else is saying you shouldn’t put pink carpet in Valensole. It was me who found the field because I wanted it to be 360 degrees when people were seated. I am still 100% ‘there’, and when I say ‘there’, sometimes it’s too much. It’s my own obsession, and always has been. I deal with it just fine. That’s why when I see the really important editors in chief at my shows, everything is fluid because they know it’s me from A to Z, and I think that’s the strength of my projects.

I get the impression there have been moments when you’ve hesitated, like launching menswear. Even though now, the third collection, it’s clear where you’re going, to begin with, there was a hesitation.

It was very hard for me, because I was in a very comfortable place with the womenswear, and I wanted to listen to myself. I wanted to do the man I had in mind 100%. I didn’t take a designer from whatever studio to help me do the menswear; I really wanted to do menswear how I felt it. It’s true, it was hard for me at that point.

What blurred your vision? Was it other people’s reaction?

In the end, I think I was focused on certain reactions and other people put me off. In fact, it became the best-selling collection since the start of the Jacquemus story; 95% sell-through, which is very rare. It was a huge, huge success. It was simple, but it was what guys wanted. I had my universe and it’s still a journey. I’m learning all the time and I make mistakes. I said the day before the show, ‘This is my first collection, but there’ll be others.’

Can we talk a little about the online boutique? It’s run by you, your dad and your best friend?

Yes, that’s right. I have done something rare in the fashion world: I have taken deliveries in-house. Everything is sent from barns belonging to my grandparents and run by a large part of my family; there’s my aunt, my stepmother, my father, my stepsister, and my best friend who used to work on Jacquemus’ images but who moved down south to change her life. That’s changed lots of things, because we all know that deliveries are key to sales. It’s mathematical, if a shirt stays on the rail for six months, it won’t sell. That’s how it is. So, taking deliveries in-house has really helped us operationally. It’s very fluid. The online shop is a major part of Jacquemus, because it’s now the leading retailer of Jacquemus, so it’s really important.

Why no bricks-and-mortar shops? The brand is old enough now; younger brands already have lots of boutiques in lots of countries.

If they enjoy losing money, good luck to them. I prefer to make money rather than lose it. Boutiques are a major investment. When I see the turnovers of boutiques, it doesn’t set the pulse racing. Having a boutique for the sake of it, no way. I’d prefer to have projects that are released, that are new, and that say something new about our world. A boutique doesn’t appeal to me.

‘Our world’, do you mean the Jacquemus world?

Yes, but not just that. If it’s an experience you want to have, why go to a boutique? What more do you get in a boutique? If it’s just for buying, I don’t know, I’m just not up for it.

‘You open fashion week and get the impression of being the eighth wonder of the world. The following day, you go back to work, back to serving people.’

And the restaurants, the Oursin and the Café Citron in the new Galeries Lafayette Champs-Élysées, are they like Jacquemus boutiques?

Not really, it’s not 100% Jacquemus. I did the art direction of both spaces from A to Z and I had carte blanche, but it’s not totally Jacquemus; they are spaces that the Galeries Lafayette asked me to

think about within their stores. There were lots of constraints, too. They’re not my boutiques, even if they’re not far from a dream space for me. I’d love a living room like the one at Oursin!

How many people work in the Jacquemus office today and how big is it?

Seventy people in 1,600 square metres.

What’s your favourite room there?

The space where we all eat together.

I was there when you opened the space officially. Why do that in the atelier on a Monday morning?

It’s the space where the fashion happens. The atelier is always separate and I wanted to put the spotlight on it. I thought it was important to draw attention to the people who work there. As everyone is, but they really are.

Who’s in the atelier? How many people and what is their profile?

Maybe 10. It goes from a lady, who is maybe 60 years old, to a fashion student who is 20 years old. It’s very varied.

My perception of Jacquemus the business, is that everyone is younger than you. And lots of people have arrived through internships.

Yes, lots of people came with internships, but the average age has begun to change now. We’ve taken on people with more experience.

It’s changed over the last 12 months? It’s becoming more professional?

Exactly. It remains a friendly, family-orientated business, but we haven’t lost anything by gaining in efficiency and organization. I don’t feel like I’m in a new world because I have a bigger building. It hasn’t changed that much.

Where do you think this desire for fashion comes from? From your mother? Was she like that?

No, not really. I don’t think so. I don’t know. It’s a weird question for me.

When I saw you at the party after the show in Valensole, I was amazed to see quite how similar you are to your family, and I remember saying to myself, ‘Ah, he’s like that, because that’s what they’re like.’

I suppose I’m the same type of human as my family. That’s why there’s never been any shock with what I’ve done. Everything is always so fluid. When I tell my grandmother that I have doubts, she understands. When we organize parties in Valensole, it feels like I’m back at my grandparents’ as a child, in the barn when they invited all the neighbours over and my father would climb onto the table, dressed as a woman, and dance with me. It was friendly and easygoing and it would do you good. Yes, I feel like I’m like that too. I’ve always been passionate about recounting things, telling stories. I think that’s why I create fashion – and as long as I have stories to tell, I’ll carry on.

Model: Mica Argañaraz.

Hair stylist: Ramona Eschbach.

Make-up artist: Marieke Thibaut.

Producer: Elena Cavagnar