From next big thing to real deal to the most criminally overlooked designer in British fashion history, Antony Price is the closest thing the industry has to an unsung hero.

By Alexander Fury

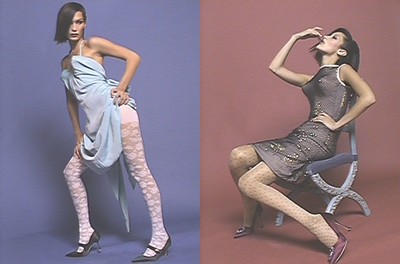

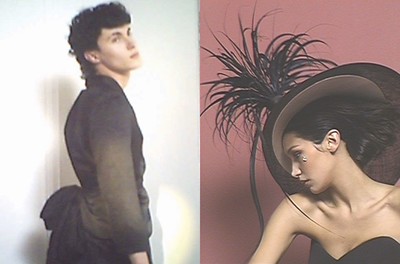

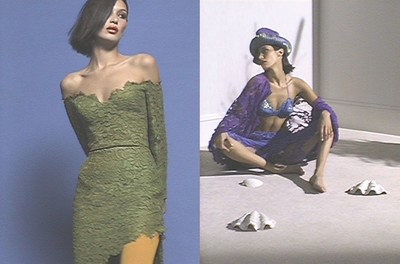

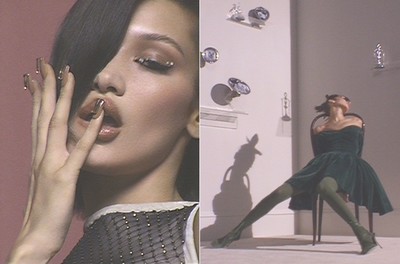

Photographs by Sharna Osborne

Styling by Vanessa Reid

From next big thing to real deal to the most criminally overlooked designer in British fashion history, Antony Price is the closest thing the industry has to an unsung hero.

Out in the English countryside – High Wycombe, to be exact – lives the greatest British fashion designer you’ve never heard of. Or maybe you have. To say you haven’t is to listen to naysayers, the most vocal of them being the designer himself, who asserts he is forgotten, overlooked, that he never really made it. If he’s being generous about himself, he may say he was ahead of his time. Which he was. Yet it is certainly undeniable that his is an obscure, insider name, a designer’s designer – particularly when compared to the starry trajectory of his achievements, the manner in which his work shifted popular culture and readdressed taste in the late 20th century, and how it still affects our eye today.

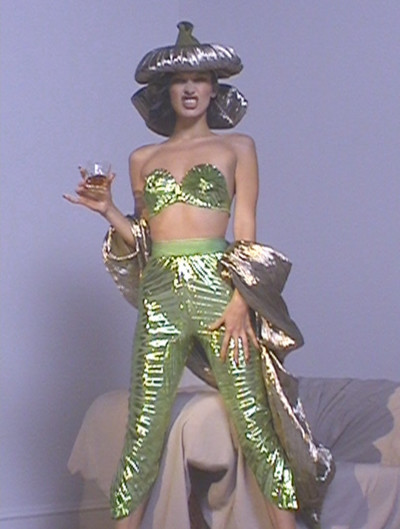

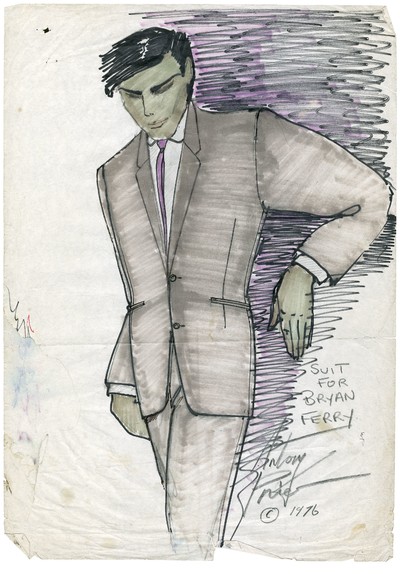

The designer is Antony Price, a name perhaps more familiar to music fanatics than fashion watchers. Antony Price has only staged six fashion shows in his 50-odd-year career, but his name appears on all eight albums by cult British rock band Roxy Music, an unprecedented credit back then. He fundamentally helped to craft the band’s image, so much so that he’s sometimes referred to as the band’s ‘silent member’. He also helped to craft a modern definition of glamour, a potent blending of past and future, male and female, reality and blatant artifice, the whole thing corseted, padded, buttressed and poured all over with molten polyester lamé. Price helped fashion – in all senses of the word – the 1970s glam rock movement in his outfits for Roxy Music and his styling of the Roxy Girls. He helped secure these avatars of a new, unearthly allure for the then-odd gig of sprawling on a white velvet sheet strewn with gold records while growling like a cross between Rita Hayworth and a baying tiger – what cultural commentator Michael Bracewell once described as a bravado reclamation of a Vegas showgirl look – or being trussed up in sex-shop shoes and shiny ciré satin, leashed to an imaginary panther (illustrated by Nigel Weymouth). Through those, and through the tailoring in which he suited up Roxy Music’s lead singer Bryan Ferry, Price predicted what the 1980s would become: wide-shouldered, slinkily hipped and expensively dressed. But in the hands of Antony Price, it was – and remains – so much more.

There’s something about the power of glamour that transcends the vagaries of time. That means that when you’re looking at an Antony Price dress, it could feasibly originate in 1979, 1999, or 2019. (Or, indeed, 1959 or 1939, with a different name on the label.) There is an immutability to its appeal. Men in slick suits and women in engineered evening gowns, executed in weird fabrics and strange hues – sickly chartreuse, petrol blue, tarnished gold – make a panorama of Price’s work, then or now, look like a corrupted frame of Technicolor film. The forms he painstakingly sculpts from cloth also survive, with an eternal appeal. Bryan Ferry dubs him one of the most remarkably gifted people he has ever met, and a ‘master craftsman’. He still has suits made by Price, as do the various members of Duran Duran, who Price dressed after Roxy disbanded in 1983. The spectres of Price’s clothes cast their long shadows across fashion every few years, when dresses become short and tight and structured, when suits become sharp. He returns when everyone thinks of glamour and is inevitably led back to those Roxy years, to Kari-Ann Muller as a Vargas pin-up made flesh baring her teeth on a pin-up gatefold of ruffled satin (she was paid the princely fee of £20 for becoming the ‘face’ of Roxy), or Jerry Hall painted blue and crawling across rocks near Holyhead (Price also made the dress for her almost-wedding to Mick Jagger in 1990). In short, when you think of glamour, you have to think of Bryan and Jerry and jacket revers and tight cocktail dresses suggestively slanting open at the crotch. You have to think of Antony Price.

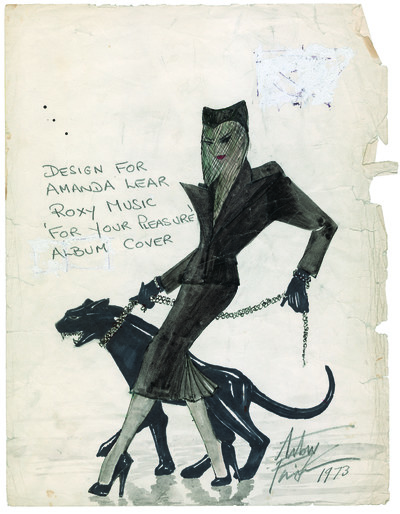

Alexander Fury: We have to talk about Amanda Lear. The ultimate Roxy Girl, maybe.

Antony Price: That panther! We actually went to the trouble of trying to get a leopard, a black panther, the nightmare of it. We would have had to have people with guns, and Amanda was going to freak out, but we couldn’t get it, so we decided to get Nigel to do an art drawing. That was the vague idea. That was 1973, right? For the second album, For Your Pleasure. It was shot by Karl Stoecker, and Bryan played the chauffeur, and we loved doing that outfit. Bryan had a huge sense of humour about that. He just loved dressing up in all these mad things. He was always going for that. Although quite straight in real life, he knew the art of putting on a show. When people have paid to see something, they need to see it.

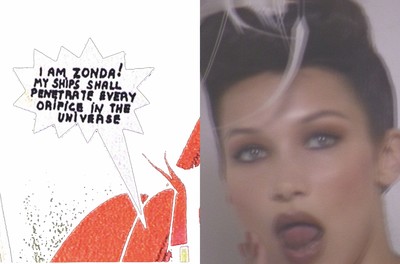

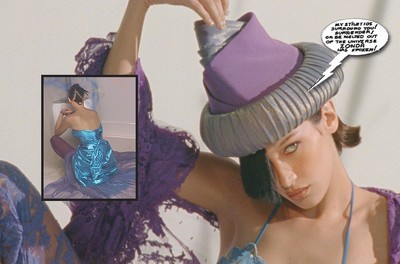

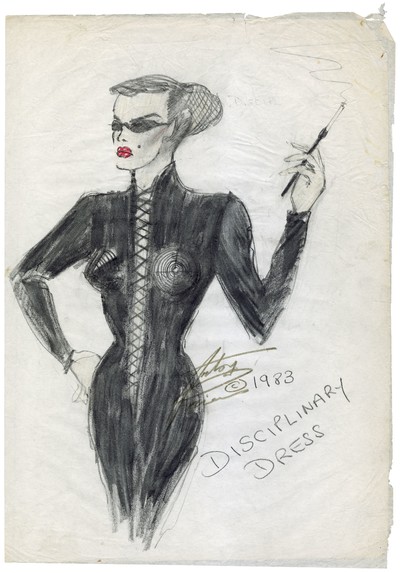

Today, of course, when everything is malleable, the physical manifestation of glamour is ever-shifting and fluctuating, but it retains certain foundations: a sense of occasion, of performance; dressed up rather than down; a feel of luxury; lustrous surfaces picking up the light; a lack of extraneous fuss and bother; streamlining. Glamour is also hard work; like its bedfellow camp, it is never natural and it is always absolutely intentional. It also rarely comes out during the day, which is why Antony Price’s clothes, painstakingly engineered masterpieces in taffeta or grosgrain, for him and for her, are primarily for the evening. Price himself, during his studies at the Royal College of Art in the late 1960s, would spend the whole day (read: afternoon) getting dressed and made-up, only to hide in the college at closing time, waiting for the caretakers to go home so he could work through the night. ‘I remember being in an article in the Evening Standard once and it was about “Them” – people from another world,’ Price recalls, laughing. ‘There was the “Them Peculiar” and the “Them Exquisite”. I had managed to take a silly picture of myself with a waist about two inches wide and shoulders that stretched off the picture, and it said “Them Exquisite”, and… who was “Them Peculiar”? I think it was Andrew Logan. It said what you had to own to be “Them Exquisite”. And every single thing that they said, I had – including a shop dummy. You had to have that. You had to have several pairs of very high-heeled shoes and various women’s shoes sitting around. I did!’ Price was a creature of the night – or maybe, the nightlife – and he staged those few legendary shows at night, too, sometimes in nightclubs. At his first ever show, for Autumn/Winter 1980, two models marched down the catwalk of the neoclassical Pillar Hall in Olympia in pneumatic biker dresses wearing crash helmets, which they tugged off to reveal… Jerry Hall! Marie Helvin! Price has something of the Ziegfeld to him. His shows were glorious, big-scale theatrical blow-outs – one necessitated the sale of a house to pull off – all notable and memorable and mind-blowing, recorded in grainy footage to be pored over with wonder. How did he do that? Did I really just see that? He dubbed them Fashion Extravaganzas and staged them for thousands of spectators who would watch multiple cinematic vignettes devoted to, say, women dressed as sea creatures or fashion versions of Apocalypse Now in a sketch called ‘’Nam’ for the show held at the Camden Palace, which opened with the music from The Omen. ‘There was another scene called ‘Marvel Kitsch’ – and it was really very kitsch,’ he says. ‘Everybody’s bits were stuck out in lumps, including the boy’s bits. Quite serious trouser shapes, all shining, waxy lipstick colours. They looked like comic-book heroes. That’s where the name came from. Each scene had a name and the theme and a piece of music.’

That Camden Palace show was like 12 shows in one!

That and the Hippodrome shows wiped us out financially. Every show we did would do that because there was never any help. It was just, ‘Oh fabulous! How wonderful.’ They would clap and drink the champagne and go home and we’d be left to pick up the bill as usual. No one would come forward to help, because it was too early. They always said that. I didn’t really understand how to do shows better until later, with my 1988 show. That was much more professional in the respect that I made four or five basic shapes and then started to put them all together in different fabrics. It’s called ‘a look’! Actually, in fact, it’s the same pattern. Before that, because I never had any trouble making patterns and I could just invent anything, I would just sit down and do far too many things. I could have spun it out much further, but I didn’t understand that. I had to do something different, instead of doing 20 versions of the same pattern, which would have underlined it better and given it more strength to sell it. But I was a showman. You see, I never had a problem telling what was good and what wasn’t, but what I didn’t understand is that other people do have a problem. I confused people. If you’re not actually into design to that extent, you can be overwhelmed by all the information out there. To be quite frank, I didn’t understand the clients at all until I started visiting them in their homes. I’ll tell you who does understand them: the women who buy the dresses for the shops; they know what’s going on in that wardrobe. But I have news for the lots of designers who I hope are reading this now: you don’t know what goes on inside women’s wardrobes until you get in there and have a look to see what else is hanging in there and what they’ve chosen. When I did that I began to realize just why people hadn’t bought such and such a dress – it was quite the revelation. I think I’m a much better designer for it. I’ve still got great ideas and I could go on spinning my own ideas forever now, but at the time, I just moved onto the next thing.

‘Everybody’s bits were stuck out in lumps, including the boy’s. Quite serious trouser shapes, all shining, waxy lipstick colours. Like comic-book heroes.’

‘Valentino used to direct clients to us,’ says Price. ‘He used to look in the shop window and say, “They’re really clever”.’ Price’s dresses were always clever. And alongside every outré Allen Jones-esque fantasy, there were sure-fire commercial hits, like curvy velvet dresses and taffeta cocktail looks cut with devastating sharpness, or indeed the eternally appealing, perpetually glamorous Roxy-type figures in poly-lamé, Price’s favourite fabric. ‘It takes the pleats and never tarnishes,’ Price tells me, emphatically, slamming a hand like a meaty gavel on the table in front of him. He does that a lot, punctuating every conversation with proclamations, in this case an ardent love of polyester. I have a gold lamé dress he made for Paula Yates in the early 1980s; he used the rest of the same bolt, dragged between multiple addresses as his career switched and shifted, to make a dress for Tilda Swinton in 2011. The fabric looks exactly the same. The most constant components of anything labelled Antony Price are a virtuoso technical prowess, a healthy disrespect for nature, and an urge to transform. Price’s clothes are cut to distort the body, chopping it up and rearranging its composite parts like a mad scientist, to create the perfect human being. He calls himself the frock surgeon and, for a price, Price can perform miracles through velvet and boning that many would assume possible only with the surgeon’s scalpel, remaking and remodelling the shape of wearers to meet their wildest dreams. The broadcaster Janet Street-Porter once famously called his clothes ‘result-wear’ – the result she meant was sex, but really the result of wearing Antony Price is whatever you want it to be. Your hips can be narrower, your shoulders wider, your waist waspier. He can rebuild you. His studio just outside London is littered with bodies, moulds of his clients’ torsos, male and female, recreated in chicken-wire and papier-mâché, pinpricked with thousands of perforations made when Price constructed new shapes on top of them. There’s something corporeal, terribly physical about what Price does. His fashion is truly ‘fashioned’ and his speech is not filled with the fluff of fashion: he talks about ‘nailing’ fabric; he tells me how he can make a drystone wall with his own hands. He’s described his dresses, with an uncharacteristic lack of deadpan self-deprecation, as ‘pure art, crafted around a 22-inch zip’. He’s absolutely correct.

As a purveyor of glamour, Antony Price is surpassed only – possibly – by Gilbert Adrian and Travis Banton, costume designers of the 1930s Hollywood studio system whose campy, exaggerated, play-it-to-the-cheap-seats style made celluloid goddesses of the women who wore them. That nostalgia for a bygone glamour was the motivation behind the visual iconography of Roxy Music – a name in itself that overtly references the branding of post-war picture houses – and of course, Price wasn’t just dressing the band members, but also the hangers-on, backing singers chosen for appearance over ability, and that seemingly endless roster of Roxy Girls. With the band, Price worked like a movie-studio costumier rather than a conventional fashion designer. Suddenly, sexuality was being used to sell music in the same way it had previously hawked everything from cigarettes to Cadillacs. Yet, although those Roxy Girls were undoubtedly sexualized, sexy, and sexed-up, their appeal was perhaps never actually the one they believed. As the silver screen had done for their parents and grandparents, the ambiguous and questioning morass of male and female teenagers for whom Roxy Music proved such a fantasy escape from humdrum suburbia were seduced not by the sex, but by the glamour.

Glamour has always had a magical power. Indeed, the word originally denoted a kind of sorcery or enchantment: ‘to cast the glamour over one’ as they put it back in the 18th century. By the 19th, it had become specifically associated with attraction, a kind of magical or fictitious beauty, an alluring charm. Ephemeral and fleeting, intransigent, difficult to pin down – essentially, a chimera. By the early 20th century, that found expression in Hollywood, through stars like Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford and Marlene Dietrich, whose respective ‘looks’ were mirages, carved from light and shadow, sculpted with padding and corsetry. In the 1970s, Antony Price performed the same trick. First for Roxy, then the world. ‘It was the leftovers of a 1970s obsession with old movie stars,’ recalls Price. ‘Thirties movies. Not 1920s, and not 1940s, but 1930s. And the main emblem of the 1930s was the star – metallic leather stars were on everything.’ As he talks, Price again strikes the table between us with his fist, giving gravitas to his words: ‘Star shoes!’ Bang! ‘Star boots!’ Bang! ‘Stars!’ Bang! ‘It was all about the picture of Mae West’s door with a star on it; I’m No Angel and She Done Him Wrong. It was ridiculous – extreme, but wonderful.’ Price smiles, his features softening somewhat with nostalgia, his voice lilting. He speaks in an accent that blurs the Yorkshire of his upbringing – born there in 1945, studies at Bradford College – with the West London of his coming-of-age. After graduating from the RCA in 1968 as that year’s star, he hung around Ladbroke Grove with a suitably starry, slightly older crowd that included David Hockney and Ossie Clark.

In person, Antony Price isn’t very glamorous. I hope he doesn’t mind me saying so. He speaks plainly, boldly, in fact resolutely unglamorously, though as a master of illusion, he can, of course, appear glamorous when dressed in his own tonic tailoring. Say a waist-cinched, jacket cut with a dandyish Napoleonic notch lapel, knotted cravat. A peacock who may have an avian version in tow. Price has spent many years breeding birds – peacocks, but also Yokohama cockerels, ornamental chickens whose trailing tail feathers can grow to several feet long. Feathers from Price’s birds were used by the milliner Philip Treacy, a friend who drafted Price in as a frequent collaborator in the 1990s to create cantilevered cocktail dresses to sit under his hats. Both men enjoy defying gravity.

The chickens are why, in person and off duty, Price is more likely to be dressed as a gentleman farmer, with tweedy flat cap and sensible footwear. He is fascinated by birds of all descriptions – ‘Ornithocheirus,’ says Price, pronouncing the name of a pterosaur genus. ‘That was my favourite thing in Walking with Dinosaurs when they did the thing about the fantastic aeroplane-sized ones’ – and his clothes often have an ornithological bent. Cocktail dresses smothered with cock feathers or scissored into plumes of silk, evening dresses named ‘Chicken’ or ‘Macaw’ or ‘Bird’s Wing’, the last engineered from a great span of taffeta buttoned to undulate across the wearer’s body. His passion also explains Price’s focus on heterosexual machismo and virility through seemingly counterintuitive extravagance. It is the peacock, after all, who is the flamboyant one; the plain pea-hen simply lets her mate flaunt it. Although Price’s women aren’t shrinking violets either. ‘Is it a good-looking man or is it a good-looking woman? That borderline of sexuality is what I’m interested in,’ says Price. ‘In the DJ Jeremy Healy’s fabulous words: “Barbie doll meets Action Man.” The ultimate extremes of male and female, both requiring padding and bulges. I don’t do stick figures.’ He’s put this more bluntly, less politically correctly: ‘Tranny-looking women who hang around with rock stars are the girls that I make my clothes for. Small arse, small waists, big tits. That’s a man’s silhouette.’

Full-strength Price – the man, or his work – is a million miles from politically correct. A war baby, his father was a Spitfire pilot who perhaps cemented the designer’s love of perfectly tailored military uniforms; his mother was, Price says, profoundly difficult, and she and his father separated when he was young. To say Price’s ideas of masculine and feminine are firmly rooted in that upbringing isn’t as cut and dried as it might first appear, as they are also coloured by Hollywood’s golden age – Dietrich in draggy white tie, Jean Harlow in bias-cut satin – images he glimpsed as a child and rediscovered in his teenage years in the early 1960s. Cinemas, after all, provided not only the name for Roxy Music, but also Price’s original shop, Plaza, on the King’s Road. It was immortalized in Roxy Music’s ‘Trash’, whose lyrics include the line, ‘Go to Plaza, where’s the trade?’ The cover of Manifesto, the album on which that song appears, is modelled on a shop window, framing a static party of Price-clad mannequins frozen in dance gyrations, like monuments to glamour in cheesecake-pastel taffetas.

Janet Street-Porter once called his clothes ‘result-wear’, the result she meant was sex, but the result of wearing Antony Price is whatever you want it to be.

Price’s career didn’t begin with Roxy Music. Mick Jagger bought Price’s clothes in 1969, wearing them for the Gimme Shelter tour the same year, when the designer was working – straight out of the RCA – for Stirling Cooper, a store established by two former cabbies, Ronnie Stirling and Jeff Cooper, in 1967. The entrance was a dragon’s mouth, the clothes were hung on pergolas. It was, it’s fair to say, extreme and absolutely of its time. And it was shortly after that Price met Ferry, along with the hairdresser Keith Wainwright of the salon Smile (who would later coif him) and the photographer Karl Stoecker – ‘My in-house photographer,’ Price says – who would shoot numerous Roxy covers. Price at that point was becoming well-known as the next big thing, following in the footsteps of Ossie Clark, who had graduated in 1965. ‘I was always three years behind Ossie,’ Price says. ‘I became his support act.’ He would stage shows that ran before Clark’s, to get the crowd revved up. ‘I was already famous or Bryan would never have touched me, because he’s a label queen,’ he says. Importantly for Ferry and his vision of Roxy was that through those fashion shows Price knew models. ‘He came up to me quite simply because I was a key to Kari-Ann,’ Price says. And to Amanda Lear, not yet Jerry Hall, but to Gala Mitchell, who Price dressed not for Roxy, but for the back cover of Lou Reed’s Transformer. The male model accompanying her on that cover wore another Price innovation, the cap-sleeve T-shirt. (Price didn’t just make evening wear; he rankles at that idea.) As with his dresses, the cut of the cap sleeve sliced the arm in the right spot, to make the bicep seem to bulge. ‘We sold millions,’ he recalls, proudly.

What Antony Price really likes is doing things; ideally, doing everything. With Roxy Music, he famously retooled the entire band, head to toe, for the shots that ended up on the inside of the debut album’s gatefold. Before he began, he says, laughing, ‘they looked like accountants, and they had divorcee hair. I had to do something with the hair.’ So to great resistance, Keith from Smile chopped it off, and Price dressed them up in outlandish Stirling Cooper samples he had in his office. For the cover, they dolled up Kari-Ann as Rita Hayworth (even if Price preferred Jayne Mansfield back then), and an image was born. ‘Really we were doing another shoot entirely, but we decided to try,’ says Price. ‘Bryan, being Libra, will have a go at everything, and when we saw the pictures at the end, we decided that we had to go with it. It’s mad and it’s fabulous. They were locked into it forever afterwards, but they enjoyed it. They wanted to do it.’

Price’s favourite enterprise undertaken with Bryan Ferry was a 1976 video for ‘Let’s Stick Together’, for which Price made everyone’s clothes – from Ferry’s white Casablanca-ish tuxedo to Jerry Hall’s tiger-striped evening gown, complete with built-in tail. Price also hairsprayed Hall’s wavy wall of frizzed curls, winged her green eyeshadow, and nailed up the curtains that backdrop the whole enterprise. ‘Cine-drape,’ he says, smiling, his voice rising an octave. Price’s often does that, when he’s recalling something from the past; it tends to be the camper excursions. ‘I did everything but film it,’ he says of the video. ‘Usually everyone makes me add a gallon of water to it, but that was full strength. And the result is one everyone remembers. I was given carte blanche for the whole design on that video. Before we decided on one idea, we had three or four different scenarios. One was a gypsy girl dancing near a fire whooping and whirling, but we decided we would go Tarzan-y and have a 1950s cinematic drape thing. There were those ruched curtains in cinemas, so we thought we’d have that. Movies, movies – of course! I remember climbing up to put them up, risking life and limb. It was quite high. The dress was a stretch thing. We painted all the stripes on it. You couldn’t get a tiger. Jerry had come over in 1975 to do the cover of the Siren LP. Bryan and I had seen her in Interview, actually, and we got her over to do Siren. We’d never met her before and she turned up for the shoot, which was… a nightmare, which Jerry has written about. Karl Stoecker had met Errol Flynn’s daughter and gone back to America with her. So we got a fabulous friend of mine, Graham Hughes, who had been working with Robert Palmer. I found the location on a geological programme I was watching one Saturday morning. We had to be out at sea, to shoot back in shore. I actually went down there – it was Holyhead. There’s a lighthouse there, too. The day I first went, it was massive green sea and enormous waves crashing against the rocks. But when we turned up two weeks later, with the costume ready-made, the whole thing had changed. It was like a mill pond, smooth, and turquoise. I had to change the colour of the costume and re-evaluate the whole thing. But it worked beautifully. We did use a slight blue gel, on the light, and we actually used car lights because it was direct sunlight above. Seals and canoeists in orange canoes kept popping up – the orange canoeists were right in the middle of the picture! We had it all, every problem. It was the hottest day of the year; it was about a hundred degrees. Jerry was melting. Everything was melting. The glue was coming apart on the gusset of the costume… It was in rubber, swimsuit rubber, but all painted with car spray.’

Price’s trousers were named Ziggurat by the designer, after supportive temple structures in ancient Mesopotamia, and ‘arse pants’ by the world.

It had been glued together?

Yes!

You resprayed it? Because the colour changed?

Yes, absolutely. We had to change completely. I had the spray cans with me and I did it through a piece of fabric with scales on it. Sapphire Mist, the paint was called. You can’t imagine how different the sea was when we got there to how I’d seen it two weeks before. Jerry was covered in body make-up, we had to get it off her in a bath. She was carried stark naked in towels onto the train at the end. The train was pulling out – the last bleeding train to London. It was hysterical, the shoot, fantastic. There were some wonderful pictures of Bryan holding an umbrella above his mermaid.

Price started as he meant to continue: he still has storyboards and sketches for the visuals for Roxy Music albums and videos, as well as for the photographs shot (sometimes by others, ideally by Price himself) for his advertising campaigns. At Plaza, the cinematically named shop on the King’s Road, Price did everything. He made dresses, sure, and suits that cost as much as a second-hand car. ‘They weren’t that expensive,’ he gripes, contrarily, even if his nickname on the 1980s London club circuit was ‘Fantasy Prices’. Yet he also did the shop-fit, designed the logo, drew the advertising (with the strapline: ‘Clothes for studs and starlets’). He even nailed garments to boards, as in a strange retail conceit, the clothes at Plaza were ordered through a hatch, dispatched by a square-jawed, devastatingly handsome henchman, who was Price’s equally intimidating counterpart to Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s Jordan, who was selling shredded mohairs and anarchy-emblazoned muslins at Seditionaries, just down the road.

Can we talk more about the shops? Because they really were a thing. It was Stirling Cooper first, right, then Che Guevara?

Stirling Cooper was my first shop design – and by design, I mean everything. I’m talking about what the clothes were hung on, the carpet, which was specially made, the lampshades. Everything was done specially and so I was a dab hand, and still am, at putting together quite serious architecture. I’ve never been asked to do it by anyone else; I’m never asked to do anything by anyone else. Surprisingly enough. I suppose I don’t push myself. The Stirling Cooper one was fantastic, it really was. A real feat. It was completely Japanese and all the clothes were on huge black pagodas. The hangers were brilliant. Everything about it was brilliant. The second shop was Che Guevara, this huge 1930s thing to rival Biba. It was a feast of deco, of black and green carpets in degraded stripes, with fountains and palms and god knows what else in it. Then I did the Plaza shop, with the blue Optrex window.

Was that yours? The first one you owned?

Yes, the first was Plaza. We took it over, Rick [Cunningham, Price’s long-time friend and former business partner] and I. That was in 1979. The window of Plaza was a cinema screen – it used to cause traffic jams because it faced north and the sun was behind it. It was very, very difficult in those days, the technology to do that; lighting a screen in daylight, which is now common place at the Olympic Games, say, was a nightmare then. Basically, it was a great shop in the wrong place because we didn’t have enough money to put it in the right place. We sold two suits a week, but when a shop took them up to the West End and sold eight in a week, we realized we were in the wrong place. There was nothing you could do about that.

I suppose it was more counterculture on the King’s Road, with Seditionaries, then World’s End.

No one was going to back it, though; it was too early for all that. London fashion hadn’t happened then, I was out on my own, too early. Again. We closed the shop in 1980. There was a show the same year that cost so much we had to jack the shop in, because it wasn’t making enough. We needed to move somewhere else and it took us some time to get it together to move to the one in South Molton Street, which happened in the mid-1980s. The Plaza clothes were quite brilliant, and the interior was something of a revolution as well. The inside of it… the clothes were nailed. I hated the look of clothes hanging on rails from the side. I thought it looked like a dreadful wardrobe, and I thought it should look like a museum. We had these boards and you turned them sideways and half a stuffed garment was on it, nailed up. Like one leg stuffed with a body inside it. They were all three-dimensional, which looked rather beautiful. Half a jacket with a tie and tits in it and everything. Also, they couldn’t be nicked. Then customers came in and ordered it through this hole. The assistant would then assess the size and then bring one up and you would then go into the mirrored changing room and try it on.

It sounds intimidating.

It wasn’t intimidating. We had great looking staff and the customers couldn’t wait to get in that mirror box with them, thank you very much! They used to come back with any excuse to get in there!

‘Jerry Hall was covered in body make-up, we had to get it off her in a bath. She was carried stark naked in towels after the shoot onto the train.’

Price’s shops were destinations – but it was the clothes that drew people there. In the early 1980s, when Michael Costiff complained to Westwood about trousers that would leave his arse hanging around his knees, she reportedly said, ‘Well, go to Antony Price then.’ Price howls with laughter when I tell him this. Apparently, he didn’t know. Price’s trousers, named Ziggurat by the designer, after supportive temple structures in ancient Mesopotamia, were dubbed ‘arse pants’ by the

world. They acted, Price himself says, like a ‘Wonderbra for the rear’, and were cut with the legs wide apart, as if straddling a horse. ‘They weren’t for skinnies,’ he says, ‘but people with powerful legs. I always liked that kind of figure.’ Many companies have copied the cut. In fact, everything’s been copied – get him on the subject of Thierry Mugler and his mouth twists slightly, though he admires the aesthetic, obviously. And, he allows, often ‘it’s not copying, it’s just simultaneous thinking’.

‘When Roxy were touring in 2001, I said to Bryan, “You’re lucky because you can remake all your old dresses in more expensive fabric, with a better machinist”.’ Price shrugs. ‘I’ve learned to hate my clothes. I’ve learned to hate them and be embarrassed.’ Since winding down his wholesale business in the 1990s, Price has created clothes to private order for a welter of wealthy clients, including, for over a decade, Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, about whom he is effusive. Another is

Kylie Minogue. Still more remain discreetly nameless, but demanding. ‘Nothing’s ever good enough anyway,’ Price says, recounting how one customer said nothing about the dress he’d made her, until everyone else had: ‘Five days afterwards, when she’d ticked off the number of people who had called to say how fabulous she looked, then suddenly, the dress is fabulous. Up until then, it is not fabulous. On the night she wears it, it’s not fabulous. People under stress want to take it out on

somebody. It’s stage fright, and who better to whip than the dressmaker?’ Price isn’t sad, he’s angry.

If you were to compare Antony Price to a single figure in the history of fashion, I’d be inclined to select Charles James. Mention it to Price and his eyebrows shoot skyward, and he shrugs, again. He’s uncharacteristically silent, albeit momentarily. That’s because Charles James is the real deal, as is Antony Price, and the latter knows the comparison rings true for both positive and negative reasons. Both are geniuses. Both have been feted and ignored in near-equal measure, their singular styles falling in and out of fashion; both created clothes for cadres of loyal clients, refining and perfecting the same methods they often invented. They were both enamoured with the potential of a marriage of mass production with creative ingenuity. Like Price’s design for a vinyl dress with zips that languidly span around the torso, one of his most complex design feats, immortalized in 1972 in British magazine Nova as part of a striptease by Amanda Lear, shot by Brian Duffy, titled, ‘How to undress in front of your husband’. Price and James also both have a propensity for attempting a specific, unconvincing illusion: creating dresses with structures trussed with layers of delicate, filmy fabric, a bit like camouflaging a tank with chiffon. As James draped the rigid carapace of his 1951 Swan ballgown with tulle, blurring the sharp lines of a structure that weighs 5.5 kilogrammes, so Price veiled British television presenter and journalist Paula Yates with a film of cappuccino-coloured lace, her figure beneath corseted to convex unreality for a 1994 Brit Award ceremony now remarkable for nothing bar his dress.

Theirs is also a shared obsession with abstracting natural forms into fabric, or with reinventing history; James frequently referenced fashion of the Victorian age; in 1988, Antony Price made a dress that resembled Scarlett O’Hara’s green velvet number, but cut it off mid-thigh. I would probably end with Price’s assertion that people will only properly remember him, and hurrah his talent, when he’s dead, which is exactly what happened with James and his big 2014 show at the Met, 36 years after this death. Maybe Price will get his show, one day, although there aren’t that many examples of his work around, in museums or otherwise. Price’s own archives fill a couple of rails and he does, remarkably, still have the pattern pieces for every single garment he has ever made. These crates of paper ghosts wait to be resurrected if Price is ever offered the kind of serious backing that has eluded him for decades. He also has total recall of virtually anything he’s made: talk to him about, say, a shot-blue taffeta men’s suit from 1982, and he’ll recall how it was shown at the Camden Palace show (and later, at Le Palace in Paris) for men and for women. It was made in a women’s couture fabric, and Price had to wash it, by hand, and scrape off the finish to allow him to manipulate the material the way he needed. Those tailored suits, incidentally, later became the uniform of Duran Duran, whose members wore Price in their ‘Rio’ video, and have ever since.

If you were to compare Antony Price to a single figure in the history of fashion, I’d be inclined to select Charles James. Both are geniuses.

Price’s work is a lie that tells the truth, to quote Jean Cocteau. It is absolutely, unapologetically artificial, yet, at the same time, it — and he — is absolutely real. That Cocteau-ism is often used as a descriptor for camp, and, rest assured, it is camp. No other word can describe Tilda Swinton dressed as a poly-lamé life-size recreation of the Spirit of Ecstasy with a two-foot pleated flange of gilt spanning each shoulder, a dress Price calls the ‘Rolls-Royce’. But as camp, Price’s work manages to be both knowing and innocent, thus doubly affective and satisfying. There isn’t an ounce of cynicism in what he does, and for all the coolness of the image he crafted around Roxy Music, there isn’t an ounce of coldness or snobbery. Witness that love of much-maligned synthetics, or Price’s adoration of decidedly dowdy Velcro as an idiosyncratically unglamorous fastening solution. ‘I was never truly fashion you see,’ Price says, meaning the elitism and hierarchy of

fashion, its exclusivity by exclusion. Price after all began his career in mass-manufacturing, and he loves the industrialization of couture, of his ideas (something which, as it happens, Charles James adored, too). He wants to dress the world. ‘I only judge things by what they look like. I don’t care who did them,’ he continues. ‘It doesn’t matter to me.’ Perhaps that helps when Price is so often lumped together with the music industry rather than the fashion world. ‘Roxy was a small

part of my career,’ he says. ‘But when I started, music people thought fashion was snobby and fashion thought music was dirty.’ The inextricable intertwining of the two is another legacy of Price, and it is his alone.

Mercurial, garrulous, somewhat ostracized by the fashion industry, but warmly embraced by friends and fans, Antony Price is the closest thing fashion has to an unsung hero in the age of digital over-exposure. From next big thing to real deal to the most criminally overlooked designer in British fashion history. As long as there are still record players, though, kids will discover his work, unfolding an album cover to see Kari-Ann or Amanda or Jerry panting and preening and camping it up, before wondering, like the audiences at Price’s early, all-too infrequent shows, ‘What the hell is this?’ Because those Roxy Music covers, regardless of their seismic influence, remain unequalled in the annals of music visuals, half-way between pop art and pop music. They – like those Mae West films, like Antony Price’s clothes – will endure, they will survive, because, to borrow Price’s words, they are ridiculous, extreme – and wonderful.

Director of photography: Gabi Norland.

Production: Ane Kruse.

Hair stylist: Cyndia Harvey.

Make-up artist: Nami Yoshida.

Manicurist: Sylvie Macmillan.

Set designer: Polly Philip.

Casting director: Anita Bitton.

Models: Bella Hadid at IMG, Tommy Blue at Anti-Agency, George Leo Manby.

Photography assistants: Jodie Herbage, Andy Moores, Sandra Seaton.

Loader: Saskia Dixie.

Styling assistants: James Chester, Eliza Murray.

Hair-styling assistants: Pål Berdahl, Jenna Shafer.

Make-up assistant: Yoko Minami.

Set-design assistants: Camilla Byles, Tom Schneider, Mila Sanghera.

Set builder: Paul Simpson.

Casting assistant: Finlay MacAulay.