In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘The fashion itself needs to have

certain qualities that can inspire

the image-makers, the stylists,

the photographers.’

A conversation with David James,

8 May 2020.

Thomas Lenthal: Thank you so much for producing something that feels so personal and intimate. I was very touched, and I found it captivating.

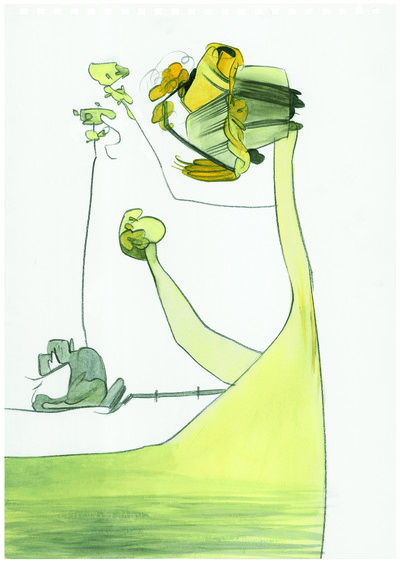

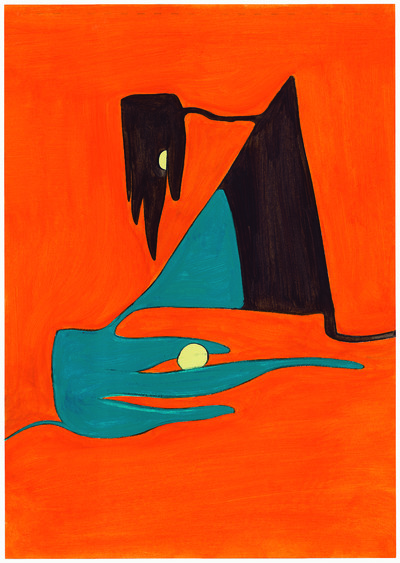

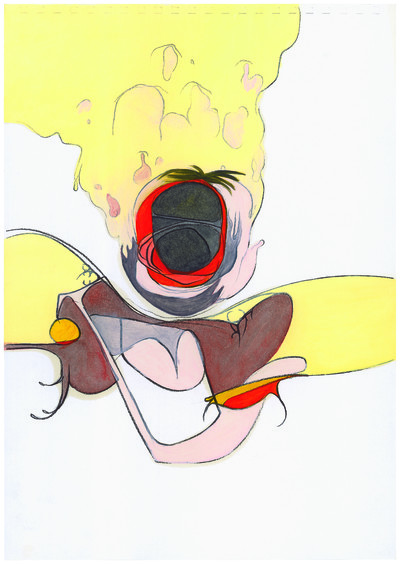

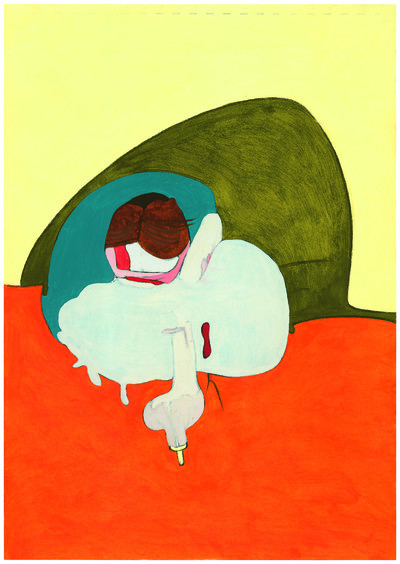

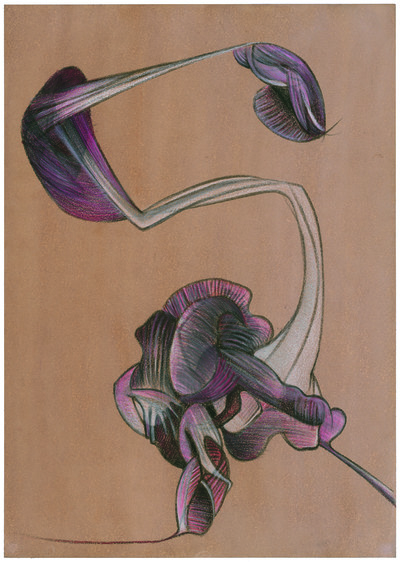

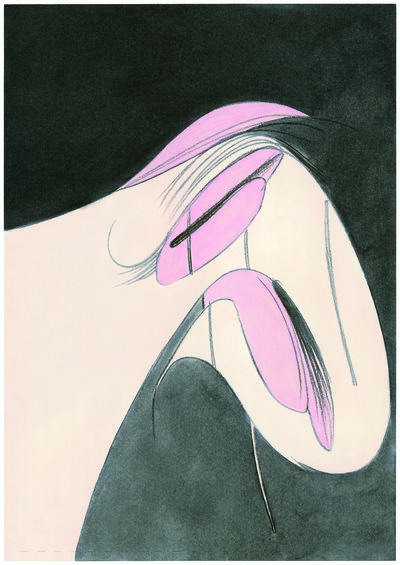

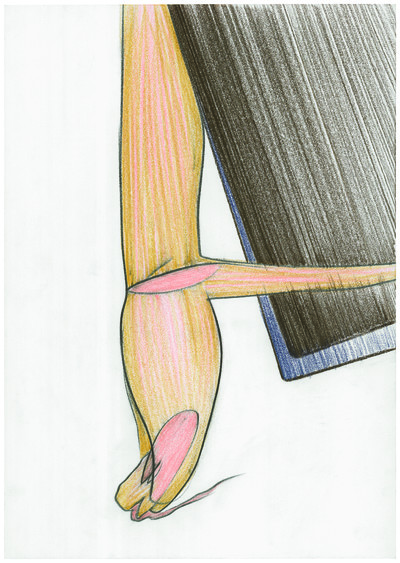

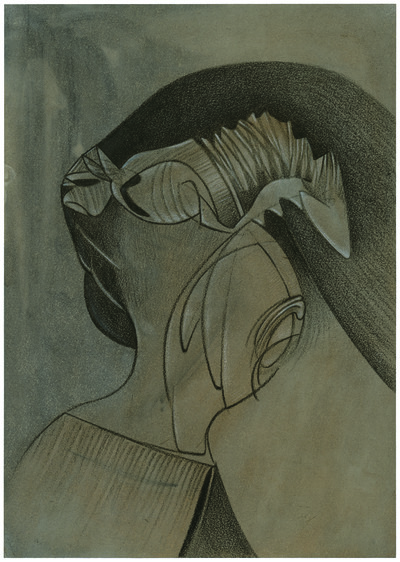

David James: It’s an interesting one. I’ve been busy with my art practice for the last 10 or 12 years, but I only started showing the work in the past three. The drawing practice is quite developed now, and I’m working on a series of paintings. I do automatic drawings all the time; I never really have any references. This was kind of interesting because I didn’t really deviate too much, other than doing my homework, doing some research, looking at all the shows, seeing what caught my attention. And what did was the full Saint Martins show. It was very accomplished, and I thought it was the right moment to focus on a new generation of designers. Somehow everything I saw in that show – all the colours, the forms, the shapes, the ideas, the casting – it all just fitted for me. This moment in time felt like a good moment to champion the up-and-coming generation. They seemed to be very tuned in to what’s going on in the wider world. I always work off intuition and instinct – that’s all we really have – and it’s the same with my drawing practice; it’s purely intuitive. There is no thinking going on; it’s an act. I just create drawings. I don’t know what I’m doing when I do them. They can be very abstract or very figurative. I took it all in and then made the drawings. I made a note of the colour palette, all the forms, general impressions, and then put it to one side and started making the drawings. I went back to it to look at the colour, and then I just got on with it. That’s how they came out. They’re sort of semi-figurative, kind of abstract. That was my intention; I didn’t want to do anything literal. I could have done, because I do paint and draw figuratively, but I felt that might stray into illustration – literal fashion illustration – which wasn’t my intention. It was more about creating a mood or a feeling connected to everything I absorbed when looking at the work of the students.

Thomas: They really felt like totems; you know, strange monsters somehow. This notion of combining this way of looking with fashion feels not just novel, but unheard of.

David: It’s interesting you say they’re totemic, because I do a lot of abstract drawings that to me are all three-dimensional. It’s like drawing sculptures. Quite a bit of my work actually looks like that, so there are different elements of my art practice in this: fabricating, painting, drawing and, indeed, sculpting elements. In fact, one of the projects is to make some of my other work into three-dimensional objects.

Thomas: They seem to be begging for that. And it was also, to me, really English. It reminded me of Henry Moore and Francis Bacon, obviously.

David: I’m a huge fan of Bacon and I admire Henry Moore a lot; that’s not too much of a surprise. I don’t really think about those artists, though. When I’m doing these automatic drawings, that doesn’t come up. These drawings are done incredibly quickly; I really do them without thinking. They don’t all work, so for every one drawing, I might do seven or eight. In that sense, it’s all very spontaneous, very impulsive. I start with the drawings, all done first with pencil, and then some of them are painted with oil paints, and some are drawn with coloured pencils, crayons. I work with all media: acrylic, oil pastels, chalks, oils. In some of my work, I use a lot of resin and hair.

Thomas: Is restriction itself a useful or necessary thing when it comes to creative work?

David: For my art practice, there can’t be any restrictions. But as a creative director, restrictions are fine, as long as they are not stifling creatively; they should be parameters. In the editorial or design realm, that’s actually quite important, because we’re usually working with a client’s vision, and they can be really good. Restrictions can be stifling when you’re not asked to be creative, or when your creativity is taken away. As you will know very well, you can find yourself in a situation where there is an incredible brief, and as you go through the process, the creative execution gets whittled down until it becomes a hollow shell. That’s really depressing. I’ve been fortunate in that I’ve been able to work with lots of really inspiring people and clients. It’s not been without its difficulties, but I find it very rewarding when there is an impetus to create great work, and a momentum behind that, a belief.

‘The rebelliousness and energy of punk were really appealing to me as a 14-year-old. And I think that has always kind of stayed with me.’

Thomas: I always think about it as an honest conversation with whoever you’re dealing. Things turn sour when the conversation becomes dishonest, on both sides, when no one is interested in saying anything meaningful.

David: I have a bit of a sixth sense for that, and I tend to back off and not get involved if it’s like that. I’ve never really enjoyed doing things for the money, and have rarely done so. I think that’s typical of our generation. When we started out, it was very much about the creative work: what you could do, how you could express yourself. It was never about the money. There was always a passion about what you could do creatively. Maybe that’s different today. Back then, of course – and I’m going back to the late-1980s, early-1990s – the fashion industry was a small place for creative work. I started out doing record sleeves and that kind of evolved into doing fashion projects. It gathered momentum in the 1990s, but of course even back then there wasn’t this complexity of media to work with; there were just a couple of basic things. It’s become a very different industry. I’ve seen a lot of people along the way who were just in it for the lifestyle, not for the work. It seems like a fun or glamorous thing to do, but I’ve been around a minute, so I can usually sense when somebody is not serious about the work. You can tell. Sometimes you get a brief and you look at the brand and you say, ‘Well, that’s never going to happen.’ I’ve seen that even more in recent years: middle management trying to impress decision-makers internally, trying to make themselves look good, and just not really understanding the brand they work for.

Thomas: For sure. I sympathize with that. What to you is a good fashion image, and has this remained the same throughout your career?

David: That’s a good question; a tricky one, isn’t it? For me, I want to feel like I’m seeing something fresh and new, like I am seeing something for the first time. Fundamentally, that’s what I always want to see. I want to have an initial reaction or response to it. Now, that could be really good or really bad, because sometimes, certainly, I’ve been very challenged by images that have really made me think, ‘Why am I reacting so negatively against that? It must be because it’s doing and saying something new. It’s hitting me and affecting my nervous system in some way.’ Sometimes it takes a while to make that decision: is this something or is it just really bad? It’s the same with art.

Thomas: It seems to me that the ‘shock of the new’ used to happen more often with the clothes themselves, somehow. The translation into fashion photography came about – I don’t know why – in a way that felt a little smoother and a little more seductive. I can’t think of any fashion imagery to which my first feeling was: ‘This is repulsive, but I should look into it a bit more.’ I don’t know if I’ve ever been startled or puzzled by fashion imagery, to be perfectly honest. But I’d be interested to understand better what experience you are referring to.

David: When I first saw Wolfgang Tillmans’ work in i-D, that really threw me.

Thomas: But he’s not a fashion photographer. He can act in the fashion context, but he’s obviously got a different agenda.

David: I know, but back then I didn’t really know that, and he was working for various publications. His work really hit me and really shocked me: like, that doesn’t look like a fashion image I’m used to seeing, that’s pressing some buttons. It challenged my notions of the fashion image, and I realized that that was kind of a great thing. It’s true that that was at the very beginning of his career and he then went on to work exclusively as an artist and rightly so, because his vision was personal and outside of any design or commercial considerations. When I want to see something new and fresh, it’s not always to be shocked, necessarily, but just to feel like I’m seeing an evolution within the industry, of imagery or a new sensibility or feeling. Of course, those have come about over time with certain photographers or image-makers, but what you were saying before is true: there first needs to be a kind of spark or inspiration that comes from the fashion itself. It needs to have certain qualities that can inspire the image-makers, the stylists, the photographers and designers. Sometimes those sorts of things are outside of fashion, aren’t they? I’m just thinking back to the grunge period, for example. We keep talking about things back in the 1990s…

Thomas: Back then, one of the factors that could sometimes be aesthetically unsettling was the choice of models. The 1990s was such an interesting time, when Steven Meisel would decide that a girl was worthy of being on the cover of Italian Vogue, and you’d think, ‘What?’ That was aesthetically challenging, yet when I think about fashion photography, I feel that it always has an element of immediate seduction to it. What could be unsettling is the styling, the model, the hair, the make-up, but the image itself, somehow, always remains in a very conventional frame.

‘I’m challenged by images that make me think, ‘Why am I reacting so negatively against that?’ It must be because it’s saying something new.’

David: I feel you’re right. The fact is, the 1990s were an incredibly productive, highly creative time. There were so many different voices, so many photographers, stylists, people doing very individual, very interesting things. There was an explosion of talent and ideas and it was a very fertile and rich period. It doesn’t seem to have been so since. That might just be my perception, because I’m looking back in a nostalgic way. Of course, when you’re in it, it’s often quite hard to see the bigger picture, but when I look back I realize that it really was an incredible moment for fashion and fashion photography and image-making. Now there are just hundreds of magazines, thousands of image-makers, so much stuff, even more now with digital media. It’s frankly very, very repetitive and a lot of it washes over me. I often get asked for advice by photographers who are starting out, and I say, ‘Save up, take a year out, find out who you are and what you want to say, and don’t start taking fashion pictures until you are clear about that. Otherwise, you’ll just become a jobbing photographer with no point of view.’ That’s what I see a lot of: imagery with no aesthetic or fashion point of view.

Thomas: Tell me then, what is a good fashion photograph?

David: In principle, it should always be an expression of fashion: the casting, the type of picture, and saying something new about fashion from a cultural point of view. What makes it really interesting right now? Maybe we’ve just reached saturation point. The industry has been speaking about this a lot, about the volume of shows, the volume of products, the volume of everything. It creates an incredible amount of anxiety, and it doesn’t seem to be a great environment for creating the kinds of things we feel we are missing. It’s overwhelming for everybody.

Thomas: I was speaking to another English creative director and he pointed out that in the 1990s a fashion story could be 8, 12, 14 pages; a 16-page fashion story was absolutely humongous. Now, in magazines – and I plead guilty – you have fashion stories that could go on for 60, 70, 100 pages, almost mirroring the inflation of contemporary fashion.

David: With those stories, you could make an edit and narrow it down to a handful of images. Sometimes, I look through magazines and I think, are they just filling up space? I see a magazine that’s 10 centimetres thick, and I think, what’s going on here? I can’t even get through them. We were talking about a time when editorially there actually weren’t so many credits to tick off. That has played a huge part in the commercial reality of magazines; advertisers have become very demanding about the credit list they expect. You end up with telephone-book-style magazines, because of those obligations. That doesn’t make for a great issue, sometimes, because you end up with 30 pages of uninteresting credits.

Thomas: Or maybe the format itself has become slightly absurd. A magazine is not supposed to be 600 pages long. Was there a defining image, reference, person or moment from your teenage years that you now look back on as instrumental in moving you towards a career in fashion, and art direction in particular?

David: I think it started through music when I was about eight years old. I believe it was a Led Zeppelin record that caught my attention. I became aware of the way people were dressing, and the suedeheads and skinheads. I remember asking my sister if there were any pop bands that dressed like those people. At that time, there was a band in England called Slade who did look like that, until they became super glam rock. So that was my first connection between music and fashion. The most striking example for me was when punk happened. I was 14 or 15, and it was an incredible moment to witness and experience. The rule books were ripped up. There was this idea that you could do anything yourself; you didn’t need to be practised or skilful, you just needed to get on with it and do it. The rebelliousness and energy were really appealing to me at that age. I think that has kind of stayed with me. I was very fortunate to inherit a technical artistic ability: I can draw, I can paint. My parents saw that in me very early, and encouraged me. I kind of knew by the age of 10 or 11 that I was going to have a career in art in some way. When I was 15 or 16, I was living in Manchester and very interested in the music culture of the time: Joy Division, for example. When I looked at the work that Peter Saville was doing, at those record sleeves, I thought it was incredible that a record sleeve could look like that – and that this could be a medium I could work in. So that’s exactly what I went on to do. When I started working for myself, I began doing record sleeves, and my interest in fashion came through music. It always did. The late 1970s was an incredible time to be interested in music because everything was completely turned upside down and changed, with punk, and then new wave. The look that Joy Division had was kind of incredible.

‘Sometimes you get a brief and then you look at the brand and you say to yourself, ‘Well, that’s just never going to happen.’’

Thomas: Can you give an example of what’s most intuitive for you in your work and what you tend to overthink?

David: What do I tend to overthink? Everything! This is a really interesting question, because in my art practice I do exactly the opposite. I really set out not to think; it’s about doing. That has always been a goal of mine, not to overthink things. That’s quite challenging. When you are given a brief for something you have to do a lot of thinking, you have to do a lot of homework, a lot of research. That’s where the overthinking can come in, because you can get a bit too overanalytical. Sometimes it’s necessary, but it really depends. In the end, really, I’ve always been good with my intuition.

Thomas: You circle back to your initial idea.

David: That circle used to be really big, but over time, you gain confidence in your intuition and your instinct and it becomes very small. Nine times out of 10, my decision-making is ultimately just based on my intuition. It has to be, even if I’ll still do a lot of preparatory research. I like first to understand the brand, the designer or the culture in some way, so I can get the measure of a project. Then I can make a more informed intuitive decision. Within my art practice, my studio is literally a laboratory. I just do experiments and the work will take me somewhere. Your subconscious is always going to tell you, intuitively and instinctively, that this is right and this is wrong; that it does or doesn’t accord with how you feel about what you’re trying to do. Sometimes I don’t even have an idea about what I’m trying to do, and it’s better that I don’t. It’s better to have an inspiration, a spark, and to see where it goes.

Thomas: In your commercial work, do you want to appeal to niche in-the-know audiences, or a wider demographic?

David: I’m easy either way, because there’s a creative challenge either way. It’s about how exciting the intention is from the client or brand. For me, it’s always really exciting when there is an idea to try and do something, even if it’s very commercial. Like I said earlier, sometimes you just know with a certain brief or brand that that’s never going to be possible. And in that case, don’t do it.

Thomas: What does success look like for you?

David: Success has always been to feel that something has really hit the mark creatively. That doesn’t always happen, but that’s always the intention. In the end, I want to get it right for the client, but I want to get it right for me, because if I’m getting it right for me, then I’m getting it right for the client.

Thomas: Excellent answer. Describe a professional disappointment and what you learned from it.

David: There haven’t been too many that I didn’t see coming and couldn’t plan for. It boils down to the human, a clash of personalities and an inability to understand one another. The worst is when people are operating through fear; then it’s impossible to do things. It has become more typical in recent years that decision-making is based on a fear of not pleasing somebody higher up or a fear of failing. It’s not done in the spirit of confidence, and that’s a big problem. When you look at the great things that are happening, they’re done in the spirit of great confidence and vision. You can sense it. It has an energy; it has an aura, just like people do.

Thomas: As things hopefully return to some level of normality, will your impulse be to explore notions of fantasy and escazpism or will you be more inclined to double-down on realism?

David: It’s all fantasy, in the end. There is always a need for fantasy. I like both polarities. It’s really about what feels right in the moment. What I care about is whether people want to say or do something creatively. Whichever direction that goes in, whether it goes into fantasy or into realism, that’s fine. But how are we going to push it? How are we going to make that relevant to now? What are we excited about here? What do we hope to achieve with this, and why? I always like the questioning, but I like the answer to be something inspiring, something new, something exciting – something incredibly creative.