In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘The important thing is to make work

that is complex and layered.’

A conversation with

Dennis Freedman, 14 May 2020.

Thomas Lenthal: You’re not keen to explain your portfolio, which I think is interesting. You seem to be one of the few creative directors who prefers to keep things a little mysterious.

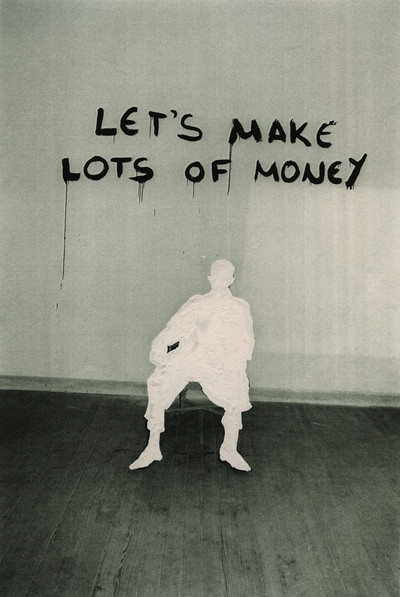

Dennis Freedman: Yes, but it goes much deeper. It’s pretty fundamental that any creative endeavour, whether it’s a piece of music, a sculpture, a painting, a book, needs to have a life of its own. The best work is open to infinite interpretations. I think anything that is too literal and one-dimensional is not all that interesting.

Thomas: The work you created here certainly possesses the quality of being open to multiple interpretations.

Dennis: The important thing is to make work that is complex and layered. That has always been my goal throughout my career. I’m pretty much a classicist; if I go back, even to W magazine, there’s always a classical foundation. When we published photographs, the goal was always that they should be accessible so that my mother, say, would get something out of the photograph, but in a completely different way to someone from the fashion world, who might bring other allusions and references to it. My mother might miss some of those specific references and appreciate it purely visually. A work has many dimensions, so it’s important to allow for that. Whether it’s a book, a movie or a dance, the best always require repeated viewings. One of my favourite works of art is Balanchine’s Serenade, which is set to Tchaikovsky and something you want to see over and over again, because every time you do, it is always a new experience. Of course, it reflects your own life, and as you age it reveals more; that’s what you aspire to.

Thomas: Well put. That’s a brave position and a rare way of approaching what we do professionally.

Dennis: I was just thinking of a good example of this. One of the things I got most excited about, which kind of explains what I believe is important, had to do with music. I love classical music, and, for me, listening to Wagner can be an overwhelming experience. I remember thinking when I was at W that the most difficult, clichéd photographs are of people singing; it doesn’t matter whether it’s the Rolling Stones or Callas, they just tend to be these stock images. I was thinking that I would love to be able to hear Wagner in a photograph, to hear the music, not just see a person singing. At that time at W – and this was the beauty of working there – we were able to experiment, so I called David Sims, as I thought he would be the person who might really relate to this. I said, ‘Dave, I want to do these photographs, but I want to hear the music, and that’s not going to be easy.’ So we auditioned three sopranos from the Met. Each one of them came to see us, and they each sang, and we chose the one soprano who we felt was the most expressive. For two days she sang Wagner with an accompanist, and Dave photographed her. For two days! And I remember thinking about the unforgettable portrait that Avedon did of Marian Anderson in 1955. That was the one of the few pictures that I

remember being completely entranced by, in which I did hear the music. Actually, I heard more than the music; I saw a human being who had struggled with adversity. So with David, we did 18 pages of these extraordinary photographs! These really were, for me, one of the things that I felt most proud of. I was very aware that this was not necessarily going to be all that easy to understand, but I really believe that there have to be readers of W who walked away from that maybe thinking a little like I did when I saw that Avedon photograph of Marian Anderson.

Thomas: Who maybe heard the music.

Dennis: If they did, that would be kind of sublime. Unfortunately, so much of that is no longer considered important for many reasons, which I think is a huge loss. Anyway, I’m very excited to see this particular project in its entirety because I assume everyone was limited in their resources. I think that limitation is so important for a creative person. When something goes really wrong, that’s always the time when you are most likely to make some sort of breakthrough. It forces you to take a different path, one that you’re not necessarily comfortable with, one that, for a variety of reasons, you would not have considered. That is such an important lesson for everyone. Certainly it gave me a chance to really challenge myself. Especially because of the psychological and emotional state that we’re all in.

‘When I was really young, I would take scissors and do lots of cut-outs, making scenes out of pictures, collages; I’d create my own magical world.’

Thomas: It always struck me, and a lot of other people this side of the Atlantic, that what you were doing at W was incredibly brave. In the sense that you were being ambitious for your readers in a mainstream fashion magazine.

Dennis: Yes, very much mainstream.

Thomas: It was incredibly bold to present a lot of portfolios that you did over the years. What I find interesting is that we’re talking about a magazine based in America mostly for an American audience, at a time when it seemed like the thing to do was to simplify everything. It was the 1990s; everything seemed somehow dumbed down. This was not the most welcoming environment for complexity, yet that was always something you were looking for.

Dennis: There’s this extraordinary misconception, one that’s convenient for our industry, both editors and brands, to think that the public is not ready. What I think is that the editors aren’t ready, some of the brands aren’t ready; some of them can’t think outside their own narrow box. I genuinely believe that it’s much more to do with their lack of vision, lack of curiosity. A lot of times the fashion world is an incredibly parochial world. With W, we travelled a lot. I really felt that was important, because it was part of what we were giving to our readers; not literally – we weren’t doing travel pictures – but we were responding to different places in the world. I remember we shot for three days in Rome. There must have been a crew of 20 people, and we were staying in this hotel: photographers, assistants, hair, make-up. Creative people, you would think, curious people. Every day we had to walk past the Pantheon. When we were leaving, I remember asking, ‘What did you think when you walked into the Pantheon?’ I don’t think it was of interest to them. Not one person had bothered to go inside – not one. I think it’s important to realize that we are the ones, in most cases, who can be limited and parochial. We assume that we have to hit people over the heads with the most simplistic material. I think that does a disservice to everyone. I was incredibly lucky because I worked at W for 15 years or more; I worked with [editorial director] Patrick McCarthy, and he trusted me. Of course, if we weren’t successful, he would have fired me, but I was lucky because I was never afraid. I always said to photographers, ‘Listen, the reason we’re working together is because I believe in you and your work and what you have to say, so don’t worry if this whole shoot fails. There’s always another chance with the next issue.’ And I think one of the most important things I did was to take away any sense of fear. This really is fundamental. It’s something we really have to think about now.

Thomas: What triggered your interest in fashion as a child or a teenager? How did you get interested in it?

Dennis: I came to my job in a very circuitous way. I was an art major and I did studio work, but I knew I was a better editor than I was an artist. I was better at asking the questions than having the answers. I ended up, miraculously, at Fairchild Publications, which was headed by John Fairchild, an unpredictable and complicated man. He took an interest in me because he realized that I loved music, opera, theatre, dance. Somehow, we started talking – we only ever talked about things outside of fashion – and one day he asked me what I was doing for lunch. I don’t even know if I had a job at that point; I may have been a freelancer in the art department. I was doing Xeroxing, I think. He said, ‘Let’s go to lunch.’ So we ended up at his table at the Four Seasons or La Grenouille. We would go to lunch a lot, and never once did we talk about fashion. One day, he said, ‘Dennis I want you to be the features editor of W.’ I just said, ‘Mr. Fairchild, I’m not a writer, I’m not an editor.’ He said, ‘No, no, I want you to be the features editor of W because you know a good story when you see it.’ He knew that I was curious. So that was it. I had a telephone and a desk, and I think I sat 10 feet apart from him. We all sat in the open space. I just sat there for a month and thought, ‘What am I going to do?’ No one asked me what I was going to do. We didn’t have any meetings. I just sat there for a long time. Then I thought, I am going to start to work with our staff photographers. I didn’t think of myself as having the title creative director, but I knew that my abilities lay there. And one day Mr. Fairchild walked in and said, ‘We’re going to become a consumer magazine.’ Because we couldn’t survive in a newspaper format. It was just at the time [1992] that Fabien [Baron] and Liz Tilberis were coming to Harper’s Bazaar and they were going to launch their first issue. No one cared that W was also going to publish a magazine. I had no help. It was me and a telephone for almost the first year. I had to do the bookings. I didn’t even know what my budget was. There actually wasn’t one: either we were going to go out of business or we would get ads to pay for what I would do. What came with that was the opportunity to take the kind of photographs that I valued. That never changed.

‘Limitation is so important for a creative person. When something goes really wrong, that’s the time when you’re most likely to make a breakthrough.’

Thomas: Which person working within the fashion industry do you most admire?

Dennis: I couldn’t pick one person. However, what I will say is that I have been so lucky to work with some of the most extraordinarily brilliant talent. I genuinely mean it, whether it’s a makeup artist, a photographer, a designer. On all levels: not just the talent, but the astonishing hard work, the unbelievable dedication and passion; it’s extraordinary. That whole ecosystem of photographers, models, hair, make-up, stylists, designers and clothes: it’s an incredible team. I don’t think the general public realizes that it takes all of that to make it work. There have been many moments where I’m sitting there watching these people creating something that is, in some sense – and I don’t mean this in a silly way – enduring. There’s one moment I’ll never forget. I was doing a shoot in Mississippi with Bruce Weber, the first time I’d ever worked with him. The entire story evolved from a conversation he and I had had about Eudora Welty, who was one of the great American writers. She lived in Mississippi her whole life. Bruce and I discovered that we were both huge admirers of her work, so we basically said, ‘OK, there’s where we’ll go. We’ll go to Jackson, Mississippi, we’ll take Eudora’s portrait, and then explore that part of the South.’ It was Martin Luther King Day, and Bruce had read in the local newspaper that one of the grammar schools was having a presentation in the school auditorium about King. He asked the producer to call the school and ‘ask if we can come take some pictures’. We meant nothing to them; this was an elementary school in Mississippi. They said, yes, sure. We all just left what we were doing and ran over to this school. They were all preparing for the programme. They were probably 4 years old up to 15. When the performance started, I was in the back of the auditorium. I’ll never forget this girl – she was about 14 – who comes out by herself and starts to sing this beautiful song a cappella. It was just her in the light. Then, in the shadows, I could see Bruce on his hands and knees on the steps to the stage with all six of his assistants. He was photographing this beautiful girl singing in a spotlight in a school auditorium. I was sitting in the back thinking, ‘Oh my God, this is possible and it’s also possible while working for a so-called fashion magazine.’ That moment was repeated in different ways throughout those years. I genuinely believe that those were the moments that made W a success. It came from an interest in people, in places, in culture, in society; that’s how that started. That’s how so much of what we did started. There’s a huge lesson to learn, especially now, when we really do have to re-evaluate the world we’re living in and what, in the end, is meaningful. I think and hope that this particular issue of your magazine will be an important one. These incredibly talented people are going to be forced to work with limited resources – I don’t mean money – in terms of materials and what they have to work with. In my case, where I have been living, everything was closed; I only had what was on my bookshelves and, thank God, there was a Staples open. If it weren’t for Staples, there would be no portfolio, and thank God they still make Wite-Out. It was incredible to me how much I learned with this whole project. First of all: why is there still Wite-Out? The texture, the tactile aspect of it, and the name itself: ‘Wite-Out correction fluid’. I discovered this archaic tool, which really fascinated me; I had to get to the heart of it. The art movement that most influenced me was Arte Povera. For example, the artist Mario Merz used stones, twigs, soil, rocks, and that was enough: ‘poor art’, common materials. The power and the emotion and the expressiveness of what he created, I find hard to match. It’s such a lesson for our world where technology and digital pyrotechnics have erased the human touch. I’m not saying technology is not important – it’s vital, I’m the first one to embrace anything that comes along – but what happens is that everybody gets seduced by the technology, so it leads the way. When Silicon Valley exploded, I was, like, ‘Jesus Christ, it’s all in their hands. We’re just holding on and letting it take us wherever it goes.’ A lot of that was our fault. You’ve always got to think, ‘How can I use it to do what I have to do?’ In so many ways, we have completely lost our way. We’ve lost the human touch. We’ve created this incredibly false, perfected world that isn’t interesting.

‘There’s this extraordinary misconception – one that’s convenient for our industry, both editors and brands – that says the public is not ready.’

Thomas: I was always in awe of the studio era in Hollywood, where they ha enormous constraints and were talking to a huge audience, yet they were able to sneak in so many incredibly complex, sophisticated, twisted, sick, funny things within a package that seemed incredibly easy to access…

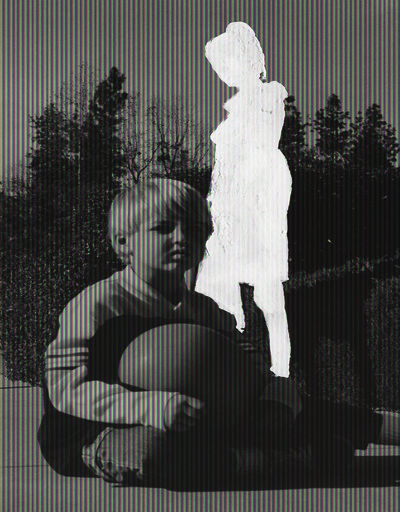

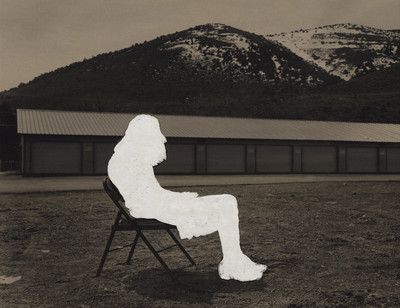

Dennis: What made that so extraordinary was that the majority of people who created that idealized world were poor immigrants who escaped Europe, arrived in Hollywood and created imagined worlds. What they made was a kind of comment on glamour, on a world that they could never have experienced. When I was really young, I would take scissors and do lots of cut-outs, making scenes out of pictures, collages; I’d create these worlds out of magazine photographs. It was my world, one I was creating in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in a middle-class Jewish family in the suburbs. And it was magical, in the way that came from my own personal vision. When I decided that maybe I would become an art director, one of the first people I met was Ruth Ansel. I was a student and I went to see Charlie Churchward at House & Garden and Ruth was there. I’ll never forget it. I walked into the room and I knew who she was. They were putting a cover together, and she turned to me and said, ‘What do you think?’ I have no idea what I said, but I remember that she asked my opinion and listened. That one thing gave me the false hope that I could actually be a creative director. Long story short, we met again later on in my career, after W had launched, and she told me this story. It’s a well-known story, but I don’t know how many people knew about it. In 1965, she was working with Dick Avedon at Harper’s Bazaar and they did a cover shoot with Jean Shrimpton. They were on deadline and it was, like, two in the morning, and they had to have the cover done to be shipped that night. Dick hated the hat Jean was wearing – they all hated it – so Ruth got out a pair of scissors and a sheet of hot pink paper, cut out a hole in the centre and put it over Jean’s face. It became, and still is, one of the iconic cover images. It was made with a pair of scissors and a sheet of hot pink paper: that was it. Dick Avedon, Ruth Ansel and Bea Feitler, and Jean Shrimpton. Think about that, and now think of everything that goes into a picture of a handbag, and you think, Jesus Christ, what have we done? Where have we gone? How can we have gotten so far and lost so much? To tie it back to where I started on this project, it really was a question of: what resources do I have? After you called me, I was like, ‘Are you crazy?’ You were talking about fashion brands and portfolios, and I’m thinking, ‘Oh my God.’ I’ve been in Long Island for eight weeks, and I only have what’s here. It turned out that I have a fair amount of past work here: issues of W that go back to 1998 and work that I did at Barneys in 2010. So I sat down, and within half an hour I imagined a photograph from my archive with one of the figures removed. It was my reaction to feeling a sense of loss and loneliness. And then I thought, ‘There used to be something called Wite-Out!’ I assumed it no longer existed, but then I called Staples. For $4.79…

Thomas: …you can make art!

Dennis: I learned so much as I was doing it. I worked on many images: some resonated when I blotted out the figure, some didn’t. Each one worked in a different way. Or, at least, each one said something different to me. It was an extremely powerful and emotional exercise.