In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘Success is when the brand you

work for is successful.’

A conversation with Fabien Baron,

7 May 2020.

Thomas: First of all, thank you for participating. I am really touched that you produced something so considered and beautiful. It feels very you and very intimate. I’m honoured you did it for us.

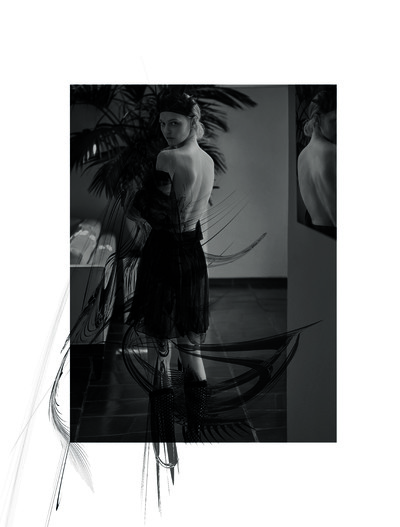

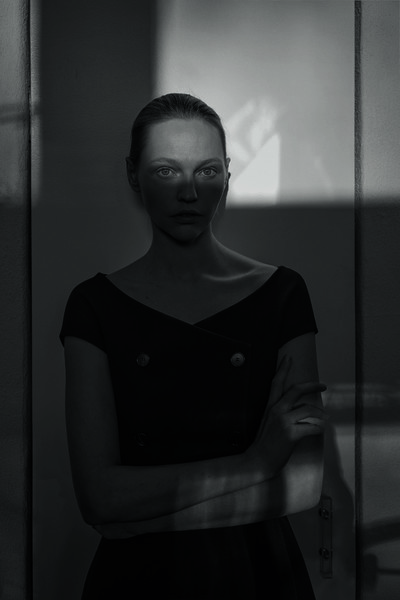

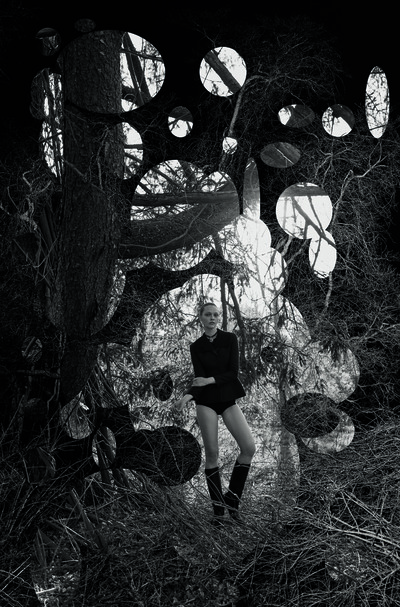

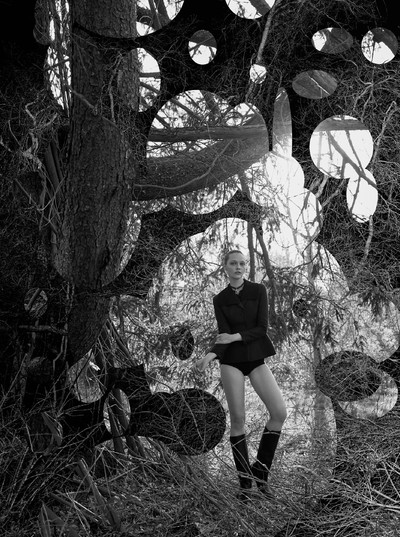

Fabien: You know, I am not primarily a fashion photographer. I love photography and I love art, and I do my own work, mostly landscapes and different things that people haven’t seen so much of. It was really nice to do a fashion story in a context where things have changed drastically, and where you don’t have the usual team available. It is really different to work under those conditions. It was both difficult, because you couldn’t rely on the same stylistic tricks, and amazing, because we had the freedom to do something really intimate and personal. Even though we kept distanced the whole time, you get really one-on-one with the person you are photographing. You don’t have a crowd around you, looking and judging and interfering in that intimacy. It felt really good, because it reminded me much more of the way I take pictures on my own, when I’m getting up at five in the morning to take pictures on the beach, or when I am in a landscape and I get into my own head space. It was a very similar feeling, and that’s maybe why those pictures are kind of intimate. That is why I combined them with landscapes, because I felt the connection between the two was very important. The model for the pictures, Sasha [Pivovarova], is a friend of mine – I’ve worked with her now for many years – so there is something knowing there. I know what she is about; I know her as a friend, and I wanted to express something that felt quite personal.

Thomas: Probably up until the mid-, maybe late-1970s, the crowd surrounding a photographer during a shoot was relatively small. If you think about the 1950s and 1960s, all those great pictures were taken in an intimate environment. Irving Penn, for example, probably didn’t have more than five people around him when he was taking his pictures. This project has a sense of nostalgia about the quality of a moment that can come through in the picture because of the less-contrived circumstances.

Fabien: It’s the way we are used to working today. In editorial commercial work, there are just huge expectations. People are used to working in a mood-board way, like, ‘We want to do this story, so we do a mood board and then copy the pictures.’ The teams are larger, and everyone’s got their own expectations and their own ideas about how things should look; there are all these preconceived ideas. The photographer then needs to be part of that group, otherwise the pictures they take won’t meet other people’s expectations. Just let the photographer take the shoot some place, give the work room to breathe, to get somewhere. That is the danger of how we have been working: you can precook the image before you’ve even made it. That said, working with an exceptional team can really take the work to the next level. With this portfolio, it was just me and Ludivine [Poiblanc, stylist and Baron’s wife] and Sasha and our kids. When you have to change the lenses yourself, everything is slower, a little bit amateurish, but the spontaneity becomes more apparent. That happened even in the way Sasha was modelling. She wasn’t doing it in front of a huge team, and that changes things. We were chatting, we talked about things, then we took a picture, she showed me something, then we stopped and had lunch, we spoke later in the afternoon and then took more pictures. Our houses are very close to one another, so we’d meet up again three or four hours later, when the light was much better. If we didn’t have enough we knew we could come back the next day, so it was very spontaneous and friendly and really open and easy. There is a beauty in that; a beauty in being able to work with total freedom, which is what it felt like.

Thomas: It certainly comes through. I want to come back to one of things you said initially, that you are not a fashion photographer. Do you say that because this is not your main source of income, or…?

Fabien: No, I say it because I don’t consider myself a fashion photographer. I have my advertising agency, I am a creative director and I develop concepts for brands. That is my main activity. Photography has been part of my life forever – since I was 16 or 17 – and I have grown into taking pictures on my own, on the side, as an artist. For me, photography is art – it’s not fashion – so that is what I am doing when I take pictures. It is my work and my art, and I do it very seriously. I have produced a tremendous amount of work over the years, though not much of that work has yet been published. There has been only one book [Liquid Light 1983-2003]. I haven’t done any shows or made any prints, but I have a huge archive of about 30 years of work. When you look at my work as a graphic designer you would think, ‘Oh, he has done so much’, but there’s just as much again in art photography. It’s a big pile and a strong body of work that remains unexplored because I’ve never put the time into doing it. It’s never felt the right moment to go and do that.

‘It’s all about if the client had fun and is happy with ‘the experience’. What about the result? You could have had the worst time: it’s the result that counts.’

Thomas: Maybe you’ll be confined for another couple of months, and you can start looking into your archives more seriously!

Fabien: I have been looking. I have an office in my building and I have started to look at the archive over the past year. When I was finishing the book [Fabien Baron: Works 1983-2019], I was looking at all the work and thinking it is time to print, to do a show, to do a different kind of book. Now this other part of myself needs to be known; this other side that is crucial to me. Maybe I need to show that to the world. I’ve kept it very much to myself, and I never wanted to show it to anyone. It was an internal search, and now that I feel comfortable, I want that work to be shown. Some of it is in this story: the treatment, the way these images are handled. I think it was important to steer this story this way, because I didn’t want it to automatically be a fashion story. I felt the moment was important, and with a person like Sasha, who is also an artist, I wanted to give a message that was more personal, more artistic and more intimate.

Thomas: Can fashion photography ever reach a level of artistry?

Fabien: Irving Penn, Avedon and Bourdin elevated fashion photography to the level of art, for sure, and many other photographers have done that, too. Anything can be art – but I can’t pretend as a fashion photographer that I have elevated the medium to that level.

Thomas: What in your eyes constitutes a good fashion image, and has this definition remained the same throughout your career?

Fabien: I look at two values: the style that I see in an image and the emotion I can feel in an image. Style is fashion, fashion is about style: you can’t have one without the other. An image needs to transmit style; that is so important and really not easy. Hair, make-up, styling, colours – there are so many variables to take into account. It’s just so complex and difficult to understand. Style needs be in tune with the time we are living in, with what is going on, and it is one component. The other component is emotion. On a personal level, I think that is so important. For me, these two things are what make a really good fashion photograph. There are other important elements, obviously, such as whether a picture is compositionally or technically correct, and what you do with the subjects in an image.

Thomas: Obviously, great models play an incredible part in the success of a great fashion picture; they bring so much to the table. When you talk about Sasha, I sense that she had a genuine understanding of the context and what she needed to do, and she gave that naturally because she is a smart supermodel.

Fabien: It is the same with Kate [Moss]. Certain models really know what they are doing. You are capturing a soul, a moment, and an emotion; that is important, if you don’t want the image to feel blank. There are emotions and feelings and thoughts beyond the eyes, and capturing those can change everything in a picture. That is the emotional side.

Thomas: Would you say that a great fashion picture is, above all, a great portrait? I’m thinking about great fashion photographers who are also great portrait photographers: Avedon and Penn, to name just two.

Fabien: Their work went so much further than fashion. Avedon, for example, did everything: he did fashion; he photographed America, like so many different types of people; he covered historical ground that other photographers never would. He was intrigued by things other than fashion. He was obsessed with Diane Arbus; you can tell he was in awe of her work when you see his.

Thomas: Do you find restriction useful or even necessary when it comes to creative work?

Fabien: It’s a good thing. When the landscape is vast and you can go anywhere you want, you can get a blank page feeling. When you are forced to shoot with restrictions – this is the light, this is the model, these are the clothes – you first scratch your head, then you find a solution. When you have the blank canvas you think it is going to come to you, but you have to go out and get it. You almost have to put up your own roadblocks, and that’s a difficult exercise. I do that with my personal work, when I have no one telling me what to do. I might take a series of extremely repetitive pictures and images just to understand what I am looking at and how I can create a true interpretation of that environment in a way that meets my own vision. As creative directors, we get restrictions in our work every day – and it’s no bad thing. You may not agree with those restrictions, and so you have to work around them most of the time, which means you become this amazing problem-solver. You develop an ability to work around things. It’s an exercise, like running, like doing a marathon every day. It’s not easy – not everyone can do it – but because you do it every day, you learn to problem-solve quickly. In the job we do, you need that type of mind.

‘I’m really attached to Dior, because my dad worked on the original logo and then I did, too. It is a cultural brand that makes people dream.’

Thomas: You need to be a problem-solver, and that is exactly what we were thinking for this issue. We had a huge problem and thought, ‘Who are the guys who can find solutions?’ And I was, like, ‘We should talk to creative directors!’

Fabien: It’s a great idea. I can’t wait to see what they have all done. To be honest, we had so many great ideas. Some would have been more fabulous, but would have required more time than the deadline permitted. Then I thought: I’m here in the Hamptons; I’m two houses away from my friend Sasha; I take pictures; I have relationships with certain clients, so that I can get clothes immediately. I felt it was the best solution; to make representations of the way I am living at the moment. It was a chance to present a certain intimacy, something personal. The portrait with things coming out of the head, almost like thoughts and dreams about nature, that felt like a pretty good reflection of how I felt. The Dior aspect was important, too. I’m really attached to the brand, because my dad worked on the original logo and then later on I did, too. It is a cultural brand that makes people dream.

Thomas: What is intuitive in your work and what do you tend to overthink?

Fabien: Every time I get into the studio I like things to find their own way, to an extent, so I tend to follow what I feel, although I may change something at the last minute. A lot of people work in a very precise way; they do a lot of preparation, come up with a specific idea, which they develop and then shoot in the studio. I tend towards a process where I get to the studio and I realize, like, this is a day for cooking, not theory. And the results are what count, so I am not afraid to throw out one part entirely if I see that it will make other parts work better. I am intuitive in that way; I let things happen. Clients, photographers, models: not everybody likes that; not everyone wants to work like that. There is this thing about ‘the experience’. For the past 10 years it has been all about ‘the experience’ on the shoot, and if the client is happy with ‘the experience’ and had fun. And I’m, like, what about the result? You could have had the worst time, but it’s the result that counts. The end result has always been my goal.

Thomas: I have tremendous respect for what you have done, because, in my eyes, one of your greatest successes has been to bring sophistication to a wider audience.

Fabien: It’s fantastic when you reach a lot of people, because you feel part of the world and affecting the wider culture, to some degree. All great artists affect the culture around them: Picasso, Warhol, Avedon. Also, of course, if your voice is heard by more people it has more impact, that goes without saying. Most artists, I would imagine, would like to be recognized by many, many people.

Thomas: Some of our peers say they are far more interested in the niche audience. They would rather have the conversation with the people who understand exactly what they are trying to say.

Fabien: That is lovely. That’s great, but is that because it’s really hard when you do something you think is amazing and then people don’t like it? There is an intimacy about that as well. To be honest, I’ve never thought about whether I was reaching out to a lot of people or just a few, or if I prefer a smaller or bigger crowd. If there is a problem in front of me, then my role is just to resolve it to the best of my ability. I am obviously interested in both audiences, because on the one hand there is the work I have done for Calvin Klein and on the Madonna Sex book, which reached millions of people, and then there is all of my own work, which I have showed to perhaps 10 people. I am intrigued by both sides; they are both valid. It depends on what you want to say. Some things are more anonymous. When you put the name Calvin Klein on my work, that is not my work, that is the work of Calvin Klein. I have been taking my own images for 40 years; there are series that I started shooting in the early 1980s, and I am still shooting the same image today, the same picture. I have never really done anything with those; it is work for an audience of one, or perhaps a few people, but it is highly personal. It is all about me, so it requires a different approach. For that, maybe I’d rather it be in a niche environment.

‘I always ask the client for the numbers: what are the sales? How did it do? Did it do well? I am always asking them: ‘Does it work?’’

Thomas: Of course. Which person within the fashion industry do you most admire and why?

Fabien: I admire designers, in many ways; I admire certain photographers. There are certain people that I feel very attached to on a creative level. I feel very close to Steven Meisel, and I am still extremely impressed by the way he works, his manner and the way he does things. David Sims, Mario Sorrenti and Craig McDean are photographers I worked with early on in their careers, and I have tremendous respect for them. There are so many people I respect, like Guido [Palau], because I think he is a creative director, more than a hairdresser. He has a tremendous understanding of style and what fashion should be. Someone like Pat McGrath, Karl Templer; I am usually very impressed by people who take their work and their craft to the nth degree, far and beyond other people’s stuff.

Thomas: What does success look like?

Fabien: Success is when the brand you work for is successful.

Thomas: Do you ask for the numbers?

Fabien: I always ask for the numbers: what are the sales? How did it do? Did it do well? I am always asking: ‘Does it work?’

Thomas: Describe a professional disappointment and what you learned from experience.

Fabien: There are a few jobs that you get involved in where you have your doubts about the relationship, but you start doing the work, and then it just falls apart and you end up not just stuck in the corner, but stuck in the basement. There is no light, nothing, and the solution doesn’t come. When that happens, you learn a lot, like how you need to tick a couple of boxes before saying yes to a job. I have learned to do that. I want the job and the work to be successful; I want it to be really successful and not fail. So I am going to make sure that I step into an environment where I am able to bring success. Each client is a case study: should you do it this way, is it good if we push them? There are all of these questions that need to be asked beforehand. I never just jump on a job. It all needs to be clear. The only job I said yes to on the spot was Franca Sozzani at Italian Vogue. We didn’t talk that much, I just said yes. I was very young, and I had turned down French Vogue an American Vogue and I was, like, ‘What kind of a moron turns down these magazines?’ Then Franca called! I knew what she was doing; I adored what she was doing. We worked with the same photographers and I admired her, so we barely said anything. She called me and said, ‘I’m looking for an art director.’ I said yes. I didn’t even think about how I would have to go to Italy, I just said yes. It was the right thing to do.

Thomas: As things gradually return to some level of normality, will your impulse be to explore notions of fantasy and escapism or to double down on realism and documenting the moment?

Fabien: As with everything, it will be a mix. I don’t like extreme ways of looking at things, because they rule out different perspectives. Both ideas are valid; it is what you do with them that will make a difference. People will want to dream, as they do in every bad historical moment. There’s always been room for dreamers. Hollywood during the war was full of that, making people laugh and giving them an escape. Comedy is a form of escapism; beauty is a form of escapism. Obviously, things have changed. Nostalgia for the way things were is going to play a huge part. Personally, I feel like going back to basics, as we all did around the world: waking up, cleaning, cooking. I think that will have a huge impact on what is happening next. And I am sure that, to some degree, fashion is going to have to go back to basics in terms of design.

Thomas: To being practical and well made, you mean?

Fabien: I don’t know exactly, but people are probably going to have to go back to their roots and consider why they are here, what made them who they are, and think about embracing their past. Returning to the simplicity of square one, and asking how best to move forward. It’s not a time for something frivolous – frivolous is not something I think would work right now.