In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

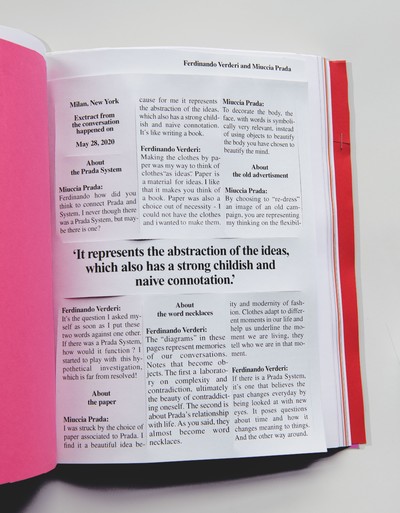

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘I don’t feel that I really have a style,

but I definitely have a process.’

A conversation with

Ferdinando Verderi, 22 May 2020.

Thomas Lenthal: First of all, thank you for having responded so positively to System’s proposal. You seem really enthusiastic about it.

Ferdinando Verderi: The reason I liked this invitation was, first of all, because after all the fashion weeks, I saw it as the opportunity to do something without a set goal, which felt refreshing. Soon after, my whole mindset completely shifted with Covid. That changed my whole perception of this project. All of a sudden, limitations began to appear. The biggest was self-isolation, which was putting me in an introspective, rather than enthusiastic mood. It felt like a chance to do something by myself. The second situation that arose was the impossibility of getting my hands on any clothes. As the constraints started to take shape in my mind, it started to feel like a project with a lot of internal traction. So I started to apply my typical process to it. First of all, I wanted to put Prada and System, these two entities, at play, and really get to the essence of things. Usually I work with a single entity in which I’m trying to find a certain tension. In this case, however, it was binary. That seemed like an opportunity to do something that could only be done in this situation. I narrowed it down to two words and I saw the chance to investigate a hypothetical ‘Prada system’: that was the conflict that I wanted to work with. It was my first idea and I stuck to it. Immediately, there was an obvious question at the heart of the project because there was a huge limitation forcing me to return to the essence of creativity: ‘What do I do when I can’t do what I’m supposed to do?’ I decided to make the clothes from paper, as it felt like the one medium I could play with to make clothes. I know you gave me all the freedom in the world, but I didn’t want to run away from what an editorial is usually about, which is the clothes. There was the physical challenge of trying to make these clothes. That obviously implied a naive and impulsive process that challenged me; there wasn’t really any science applied to any of this. I made the clothes from memory and that sense of naivety made sense in contrast to Prada’s intellectual processes. In this project, I wanted to create a juxtaposition between the complexity and abstraction of the brand and the primitiveness of how I brought it to life. Prada to me is both. The whole portfolio is like a canvas on which I am having a conversation with Mrs Prada. That was part of the plan from the beginning: I created these clothes and these diagrams as a starting point for a conversation.

Thomas: One thing that has always impressed me with Prada is the relationship between its size and the level of complexity and sophistication in everything it does, makes, imagines, and wants. It has an almost revolutionary attitude towards the contemporary world and the world of fashion: it’s a top-10 brand that operates almost with the ethos of a tiny brand. I find it very brave that it appears not to worry about being puzzling, while the contemporary commercial world gets less puzzling.

Ferdinando: The reason I relate to it and feel this chemical attraction is because Prada has led as a challenger brand; it has challenged the status quo and conventions of fashion. It has demonstrated that beauty is a philosophical concept, and that a brand can remain an independent thinker. It thinks against convention. What I try to bring out in my work for Prada is the independent voice of a challenger, one that defies scale and the idea of a single-minded definition of itself, one that embraces fragmentation and rejects the idea that things are finished, perfect and sealed. In a way, this editorial brings that to life too. It’s obviously not an advertisement; it comes from a different place. Things start for me with an intuition, which is obviously very immediate, then I reverse the process and articulate the thoughts that allow me to understand what the idea really means. After that I need to make sure that none of this comes across, so that when you see it you can still love it during the few seconds you’re exposed to it.

Thomas: That’s what I had in mind. There is a depth of meaning that is elaborate and complex, yet solid. And that gives birth to something that is incredibly direct, yet conceptually strong and has a measure of enduring humanity. It’s sentimental, yet deeply intellectual, which few people are able to bring together.

‘Fashion has this mundane quality of being something looked down upon, but it also has a visceral power that makes people love it. I love that contradiction.’

Ferdinando: This portfolio has become a quick example of how my process typically works. I’ve tried to understand what it means, but I don’t have an answer; it’s just an investigation. I don’t feel that I really have a style, but I definitely have a process. It’s ridiculous to say I’m an outsider, but I try to maintain an outsider’s perspective, one that tries to mess with things a little. I have a sense of depth and respect, but I always try to create a little trouble. I want to test the limits. That’s why I do it, to test the limits until they break, not aesthetically, just conceptually.

Thomas: I’m interested in the notion of constraint. I guess that you’re the one building the constraints. I don’t see you being subjected to a lot of constraints.

Ferdinando: Most people in our profession have a design background, they can do things themselves. I have zero technical skills. I have a very theoretical background. There’s nothing artistic in my studies at all. I studied economics. My high school was focused on philosophy, Latin and Greek. That stayed with me as a mental pattern, because obviously that’s where your way of thinking is formed. I studied economics at university, which was almost like a prank I played on myself. I did something I completely hated, I wanted to see how far I could push it, learning to like something. That went a bit far, but it left me knowing what I wanted to do, which was this, even if I had none of the supposed necessary skills. I had to create skills differently, and my thinking process is my skill. I became better at articulating my intuition and explaining it to others in a way that it becomes tangible even if it remains formless. Soon after, I started to work with people who could give shape to things. Before that, it had been hard for me to give form to something, so I forced myself to stay abstract with ideas. When I work, I don’t use images until very late in the process; I just use words. I do meetings with words, to explain where the idea comes from. I am interested in where the tension lies.

Thomas: You’re saying you’re very conceptual and not involved in material things, yet the notion of the handmade is extremely present in the graphic solutions you find.

Ferdinando: That’s because I had to accept that the only way to bring things to life directly was to use my hands. It was a limit I had to cope with. I had fun doing this editorial with my hands. Actually, I felt at home, because my whole perspective is formed by this limit.

Thomas: I can think of at least two of our esteemed colleagues who have absolutely no technological skills: Marc Ascoli and Peter Saville. Marc Ascoli only uses words, but in the way a poet would use words; he’s not conceptual in your sense. Meanwhile, Peter Saville has to rely on other graphic designers because he can’t use a computer either. It’s so interesting that three creative directors who I consider to be among the more interesting of our times happen to have limited digital design skills.

Ferdinando: My mistake, my perverse detour, is the reason why I can now express myself a certain way. I still cope with that paradox, but I don’t think it’s because of it, it’s regardless of it. I’m not giving all the credit to the limitations, but there is an argument for it.

Thomas: This notion of limitation is crucial and interesting, I was talking about constraints within the commercial world, the kind of constraints we quite often have to deal with, and wanting to better understand whether you saw constraints, like a brief, as interesting or a nuisance, something that needs to be questioned.

Ferdinando: I get so involved in the DNA of a client and try to visualize it so much that I almost come up with a brief myself, a parallel personal brief. It’s not that my clients don’t give me the brief, they do, but I have my own in mind as well. It starts from trying to break those limits or trying to bend them until they break. For me, a constraint is a necessity. When this editorial came, the constraint became obvious very quickly – there were no clothes – but I was going to look for something else to test, for sure.

Thomas: You said that this was what you always wanted to do. When did that become clear in your mind?

Ferdinando: I didn’t know what I wanted to do, but this felt inevitable. I have definitely always been attracted by fashion as a window into self-expression that would allow a fast-paced rhythm. I sometimes think I would have been an architect if I’d had more patience; I really love architecture, but fashion is a contradiction, and I love that. It has this mundane quality of being something looked down upon, but it also has this visceral power that makes everybody love it. I’ve also always been fascinated by the idea of an industry that has its own rules. Fashion images captured me very early in my life and there were a few that really struck me in my teens.

Thomas: Which photographers’ work struck you in that way?

‘It’s ridiculous to say I’m an outsider, but I do try to maintain an outsider’s perspective, one that tries to mess with things a little.’

Ferdinando: If I had to narrow it down to two in fashion, it would have to be Juergen Teller and David Sims, in different ways. They are two different individuals, but I felt that they both had something extremely subversive. I loved the fact that David Sims was basically creating independent images within the system and I loved that Juergen had a process that felt completely free and made the system need him. They embodied this contradiction that I thought was brilliant. There were also the photographs of Thomas Ruff or later Wolfgang Tillmans, which brought other things together: the idea of authenticity, objectivity and truth, the idea that an everyday image can be abstract and the fact that an image is an object. There were layers of complexity that suited my interest. I was living in a provincial town in Italy. I had never met a photographer; I was years away from meeting anyone in this world.

Thomas: Why don’t you take photographs yourself?

Ferdinando: Because I don’t feel the need for more photographs. I’m more interested in testing the limits of a form that an idea can take and in testing the limits of collaboration, than in doing things myself. It’s part of the whole game I play, seeing where things bend.

Thomas: But you’ve directed many of your own films.

Ferdinando: I don’t see myself as a director, nor my films as films. I just see these things as the expression of an idea. I started with the Versace, Versace, Versace film, which was the first directing I did. I had this idea that was very simple in my head, but had to be precise. So I had to do it myself. Then it became something that I was asked to do more and more. Every time the process is about being true to the idea.

Thomas: Another creative director was saying that the fashion world was actually parochial and conventional.

Ferdinando: It’s also a generational thing. My generation grew up in a world with these hugely prestigious giants who you couldn’t imagine challenging. Then all of a sudden, you have no choice but to challenge them.

Thomas: It’s interesting that in an industry that prides itself on being creative, the processes that have been in place for a while now are fairly stifling. So you can arrive with a measure of innocence that is a strength.

Ferdinando: I have to believe that or I’ll have to become an economics professor. In a way, I feel like you’re better off doing things that you don’t know a lot about. I mean, I have a deep fashion culture, but I didn’t have a very deep culture of the process of creative direction in fashion. When I was a teenager, I would read the credits in fashion magazines until the magazine fell apart, but I had no idea how someone would work to create it. I had no idea this profession existed until later. I never actually worked until I started working. I was in an academic environment. My head was completely somewhere else, until I started working on a project with two friends. We had this very experimental set-up and were trying to challenge the status quo of communications. For me, fashion was the target. I felt that what the world was going through needed to happen in fashion, too. I said, ‘I am a fashion person and I feel the need for change. I can’t be the only one who needs ideas to be multi-layered, for things to be challenging, for things to be wrong, in a way.’ So I just started there, after two months someone from a very major brand reached out. The were looking for new people with new ideas and I began in the middle of that world, at the very centre of it, behind the scenes. I created my own experience by working with the president of that company on ideas. Not on execution, just ideas and creative strategies.

Thomas: Let’s return to your portfolio. Can you talk me through it?

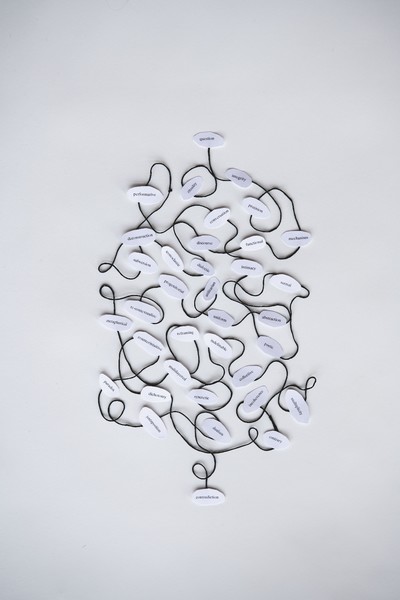

Ferdinando: One of the images is 20 years old from Prada with Angela Lindvall, to which we applied the new clothes. It’s a bit of a break in the narrative, because it’s important to show the relationship with the past. I feel like that image is a bit of a time warp because you instantly question the relevance of images and their timelessness. It’s an image that could feel new now because people are copying that style, but it also feels very dated because you’ve seen it before. The collection is new, so you wonder: was the new collection a reference to the old one? No, it wasn’t, but it absolutely looks like it could be. It creates a lot of questions that I think Prada is perfectly comfortable with and which I love. I wanted just to hint at one of the conversations; it’s like a deep dive into a different train of thought that I’m having. The other things are these mind-maps that are part of my larger discussion with Mrs Prada. One starts from this idea of contradiction; it just has everything in between. It definitely acknowledges the beauty of the Prada process’s complexity and its comfort with that complexity. Then there’s another image, which I find even more important. I wanted it to be simple and precise: it’s about the relationship between the idea of fantasy and reality, and the idea of clothes and tools. The idea is that clothes are tools for life and life is a place where your fantasies can be realized. Fantasies allow you to create new clothes in the case of

Mrs Prada or Fabio [Zambernardi], or dream about wearing new clothes in case of anyone else. In the context of this project, it’s important to remind ourselves of a sense of reality and how something so practical as clothes-as-tools and something so evanescent as the idea of fantasy can co-exist. Perfectly coexisting in the circle of life. For the rest of the images I just wanted to show the clothes.

‘This portfolio is like a canvas on which I’m having a conversation with Mrs Prada. I created clothes and diagrams as a starting point for a conversation.’

Thomas: You took the pictures?

Ferdinando: Yeah, I took the pictures at home.

Thomas: You say you have no skills, but you take pictures, you make films and you put type together. You have all the skills! What are you talking about?

Ferdinando: All these things are quite instinctive; they were led by necessity. The model, Sara Blomqvist, kindly took part. She’s part of the Prada community. The creative relationship we have is based on the Prada woman. She is in it as another element of the Prada system.

Thomas: And the colour red?

Ferdinando: That just happened. I had it at home. The most striking piece of this collection is pink. I loved the wrongness of pink and red. Nothing special about it, it just worked well in the first image. I started to feel that a palette was forming because one piece of clothing was pink, another that I wanted to shoot was brown, the printer object was brown, so I added pink and put red behind it. That’s all we needed. There’s another piece where the skirt was pink and it just became an exercise in reduction, even the palette. So I forced myself to use these three colours.

Thomas: A question that jumps to my mind at this point. You live in New York. How do all your concepts of complexity, multi-layered meanings, ambiguity, and poetry work in contemporary America? I’m not talking politics, but what is the commercial merit of this sort of attitude in contemporary America?

Ferdinando: New York is now very much part of my identity, 100%, even though the people I’m working with now are in Europe. New York has this dynamic that questions status, and is now fundamental to me. I could not do the same work if I were in Europe. Sometimes I think New York is my biggest love. I made some really hard choices for this city, but I do owe a lot to it. New York pushes things to their maximum level. I’m very comfortable with a place that is a lot of everything or very little of anything. For me, Europe just feels too familiar, because I was born there, not because of the way it is. New York continues to feel like something extreme, a place that loves extreme natures, emotion, energy, competition, rhythm, density, diversity, and a desire for social progress. It’s important for me to be in extreme places. If I wasn’t here, I’d probably be somewhere completely isolated.

Thomas: So you’re channelling New York energy into European brands without being American in the way you approach things. That’s what I find puzzling and unique in your position.

Ferdinando: My professional identity is really connected to New York. There are things that I developed here. Like this fascination for the paradox of something being extremely commercial and extremely independent or avant-garde. This is something I feel New York is made of, and which has made me who I am.