In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘I like an image with few elements

and little artifice.’

A conversation with Franck Durand,

10 May 2020.

Thomas Lenthal: Thanks for your portfolio. It’s been such an exciting exercise as we’ve realized just how personal each creative director’s response is. Could you walk me through yours?

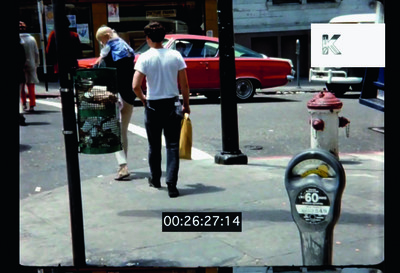

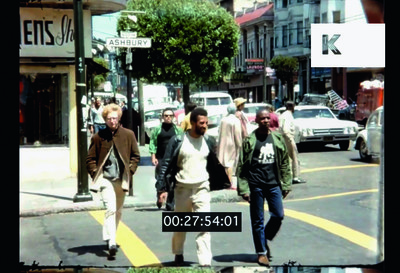

Franck Durand: Basically, these are the kind of videos I love and collect. I didn’t actually know the videos that are in the portfolio beforehand; Gauthier [Borsarello, designer and stylist] had posted them not so long ago. They show San Francisco in the 1960s in what was, in terms of style, the hippie neighbourhood.

Thomas: Are the videos drawn from silent vintage Super 8 footage? And are they part of a larger body of work?

Franck: Exactly, an image bank collected the videos, but it doesn’t record where each is from or who made it; they’re all “home” videos.

Thomas: Have you been watching this type of video for a while?

Franck: Yes, I find home videos are intrinsically very touching; they capture a moment in time, which is always quite fascinating.

Thomas: Walk me through the process for the portfolio. It looks like you created screenshots onto which you inserted credits mentioning different brands?

Franck: Not exactly, which is precisely the most interesting aspect. I asked Marc Beaugé to add what are almost like credits to the image by trying to be a little more narrative, as if we were telling a short story. I thought it was interesting to stick closely to what you can see on the image. We placed credits like Clarks and Levi’s, which are potentially genuine, on the images. The clothes haven’t necessarily changed. We even added possibly vintage or personal clothes into the archive images. And Marc wrote a great text. This is exactly the type of thing that I enjoy doing. My personal tastes are undoubtedly part of what I sent back to you.

Thomas: That’s exactly what I find so entertaining about the whole exercise: everyone we asked came up with a unique visual response that also – consciously or unconsciously – reveals their personal view of fashion. Are restrictions useful or even a necessary part of the creative process?

Franck: I think so. I was a little freaked out when the System proposal came through, and it seemed to be a free-for-all. Personally, I prefer having to deal with restrictions, particularly in stylistic exercises. It’s actually part of what I like about what I do: having to create something with what I have. It’s essential to me.

Thomas: What makes a good fashion photograph or a good photograph, more generally? Have your ideas about that changed over time?

Franck: A good photograph is one that best suits the requirements of a particular client. A photograph that client X finds beautiful could be a disaster for client Y. It all depends, but essentially, I am fond of an extremely pared down and minimalistic aesthetic. I like an image with few elements and little artifice.

Thomas: It’s amusing because three quarters of the British creative directors are obsessed with the narrative dimension of their images. I’ve always had the impression that that’s really not a French thing; that in the French way of thinking, the narrative aspect of photographic images is sometimes incidental, of secondary importance in any case.

Franck: Yes, what distinguishes French creative directors is that, even if they can be inspired by stuff from the UK or elsewhere, they will always strip back and simplify.

Thomas: You’re referring to the notion of the essential, that idea of basic outline to reach another level or to capture something else?

Franck: A sort of sincerity, of genuine contact with something palpable. A moment in which interaction is possible. We’re removing the barrier or the distance between how we imagine fashion and reality.

Thomas: In that sense, there’s a direct relationship with the character you’re shooting?

Franck: Yes, we’re trying to capture their sensitivity and emotions, to ‘feel’ them, in a way. The concept of fashion photographs can involve a kind of artifice that creates a certain distance. I rarely go in that direction.

Thomas: Do you remember a particular moment, image, reference or person from when you were growing up that set you on the road to a career in fashion?

Franck: Yes, it was all a mix of contradictory elements. The key moment was when I was 14 or 15 at a boarding school in Loches in the Touraine region. It was completely in the middle of nowhere. A friend of mine had family in London and he came back from a trip there with i-D and The Face, which I obviously didn’t know about. I was kind of shocked to discover that such crazy things were happening in the world.

‘What distinguishes French art directors is that, even if they can be inspired by stuff from the UK or elsewhere, they will always strip back and simplify.’

Thomas: So that was The Face during Neville Brody’s reign?

Franck: It must have been during his time.

Thomas: Do you remember a cover?

Franck: Yes, there was one – perhaps not that particular one – that showed a very cute blonde model called Mizzi, dressed in Vivienne Westwood, sporting a crown. It was during that era, in any case. Later on in my journey, it was Marc Ascoli and Nick Knight’s work for Yohji [Yamamoto] that completely turned my world upside down. They aroused emotions that I’d never felt for something like that before. For someone who’d never seen images of fashion like that, it was a completely new world.

Thomas: Has your way of working, your approach, changed since you started out?

Franck: It’s changed over time because back then I thought that beauty was essentially found in what could be tied to photography and fashion. I believed that fashion and images could bring beauty to our lives; then that changed. My approach is no longer centred exclusively around that particular aspect and, with hindsight, I’ve also become critical of our profession to a certain extent. I also think that between my high-school years and today, the world has changed considerably and so has our profession. It was much more like a craft.

Thomas: It’s interesting that you mention the idea of craft, as many of us in the profession used to discuss how we needed time to work properly, similar to craft artisans. It’s true that until, let’s say, 15 years ago, there was a sense that you could take the time you needed to do things properly. And then little by little, the pressure of new media brought about an acceleration in production, which in turn compressed time in a strange way and into which people settled more or less comfortably. There are those who haven’t adjusted and others who accept it as an unavoidable commercial imperative. The fact remains that we’re somewhat nostalgic about the idea of having enough time.

Franck: Yes, it’s something we all reflect on. There was a period when you could take your time and if the client wasn’t satisfied with an image, then you simply had to continue working to find the right one. Nowadays, clients pressure you to keep moving on to the next idea in order to have as many images as possible. That’s the stark reality for all of us. It’s become a matter of quantity, rather than quality.

Thomas: Which is the least intuitive aspect of your work and which flows much more easily?

Franck: I have the impression that if I don’t have a clear idea beforehand of what I am going to do and what I can bring to the table, then I simply don’t go there. I need to be able to imagine the work in its totality before I can start.

Thomas: You mean that if you don’t have an initial flash of inspiration, then there’s no point?

Franck: If I don’t find an overriding theme, then no. If I find one, then I have the ability to create a wide range of possibilities that will be in tune with my work and who I am. There are many incredible brands that I totally respect, but for whom I simply couldn’t envisage working because I wouldn’t bring anything to the table.

Thomas: Why do you think that is? To give you some context, many of our fellow creative directors have said that they won’t take a job unless they are able to be in direct contact with the decision-maker, in this case the fashion designer. But no one so far has said that there are brands they respect, but with which they wouldn’t know where to begin.

Franck: I enjoy being able to develop something; it’s satisfying being able to bring something to the table. There has to be positive evolution in what I can contribute. I’m not going to name names, but if a brand has too many guidelines, then what I actually enjoy doing just won’t be satisfying. Ultimately, that would result in my contribution being diluted and bowdlerized.

Thomas: You wouldn’t be able to provide the full service?

Franck: I really respect the notion of work and of work well done. There are many things that I really like and that I respect because they are well done. I like it when I can contribute something.

Thomas: Put simply, you prefer an ailing patient to a healthy one?

Franck: That’s more or less how I position my practice and what I like to do. For example, I can’t see any interest in working for Prada, because it’s great as it is. Certain of my clients were potentially sick, but not all of them, even if some of them had certain weaknesses.

‘There was a period when you could take your time. If the client wasn’t satisfied with an image, then you simply continued working to find the right one.’

Thomas: In an ideal world, do you prefer your work to appeal to a more niche and in-the-know demographic, or are you aiming to appeal to a wider audience?

Franck: As I don’t really know either, I do as I see fit; I don’t do it for one side or the other.

Thomas: But do the accolades of the niche interest you more than recognition from the general public?

Franck: What is important and interesting is having the feeling that you’ll be able to do something, then doing it, and finally receiving positive feedback. That’s also where you can find satisfaction. I’m not asking myself if I will appeal to one or the other; what interests me is that my contribution works. Creating great work that doesn’t reach anyone and that doesn’t keep the economic engine turning is pointless. It’s not in my nature to think, ‘Never mind, let’s do it anyway, even if only four people will appreciate it.’ What’s interesting is when a doctor restores the patient to good health.

Thomas: Which figure in fashion history do you most admire and why?

Franck: The person who immediately springs to mind is Irving Penn, for a particular reason. At the beginning of his career in the 1940s, he already had a specific photographic style that he was able to reproduce until the end of his life. His work had a common unifying thread: there were never any low points; he remained constant, without betraying himself. He may have changed models and stylists over time, but his work remained constant and relevant. The same can be said of other photographers, some of whom only shot one great photograph in their whole lives, but Irving Penn is the one who springs to mind.

Thomas: Can you describe a professional disappointment? For example, other creative directors told me about their disappointment of only realizing they were losing a client when they saw something on social media…

Franck: A very long time ago, I found out about something like that during a lunch; everyone knew – except me.

Thomas: What did you learn from that experience?

Franck: It’s always disappointing on a human level above all. You can’t compartmentalize work, people and life; it’s an organic whole. You have to be able to take a step back; they are life experiences rather than professional ones. You have to face disappointments and frustrations every day and learn how to live with them and put them in perspective. Being bitter about things would be the worst outcome.

Thomas: When pseudo-normality returns, do you think that you’ll want to produce images that are dream-like or escapist, or will you lean more towards a documentary and realist style?

Franck: It wasn’t planned, but my subjects for this season are all linked to a form of hyperrealism. They express my desire to employ the least artifice possible. So that’s a mood that suits me for what may be coming. I don’t know if it’s due to a general groundswell or not, but we all know that in fashion photography, we do tend to go suddenly in the opposite direction of what we’ve liked for a while. Perhaps we’ll see an exaggerated trend in completely the opposite direction, maybe not immediately, but in the months to come.

Thomas: Do you think that your penchant for a more minimalistic style will connect with something people might have discovered during the lockdown?

Franck: Possibly, but I don’t think there will be a single direction. On an individual level, you don’t have one single desire, you can have three or four, which are sometimes contradictory. Consequently, things are going to be mixed up in ways I can’t really predict. No one single image will come out after lockdown, and everyone will have their own personal interpretation. Perhaps even large-scale oppositions will be at play. I do, however, feel that ostentation will take a hit.

Thomas: It’s not unreasonable to think that people will keep a lower profile during an economic crisis.

Franck: It might have the reverse effect; perhaps people will also want to leave the doldrums and we can use images to make them all dream. It all depends on what constitutes a dream and we don’t all agree on that! We won’t see one type of reaction, but there will be a genuine response to what has, despite everything, been a shared, global shock.

‘Creating great work that doesn’t reach anyone and that doesn’t keep the economic engine turning is, in my opinion, pointless.’

Thomas: Do you miss our professional context? You know, travelling to a location to shoot photos, getting models in, meeting up with teams all over the world. All that intense movement. Do you want to return to that life or have you enjoyed life without it?

Franck: I used to be intensely scared of flying and was never that happy to travel. Then I managed to overcome my anxiety and began to enjoy flying, even though it’s somewhat controversial to say that nowadays. I was really happy to beat my fear and go all over the place, putting together teams that met up on location. But limitations suit me really well, too: I like the idea of being able to work effectively with what’s readily available. It’s going to be really interesting.

Thomas: My last question is somewhat melancholic. Do you think that it’s still possible to be unique nowadays and is that even valued today? Having a personality and a stance not necessarily in sync with the contemporary world, having different points of view – does that still have value today?

Franck: Yesterday or the day before I came across a text by Socrates in which he was complaining that the kids had no respect for anything and that the world was a much worse place; a very banal thought in the end. Even if we have the impression that everything changes, the underlying subject actually remains the same. Being unique in one way or another, the circumstances are different to 50 years ago, but nothing ever changes really. You have to keep a certain distance from shared taste – that’s what is important.