In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘I love democracy – but I miss quality.’

A conversation with

Giovanni Bianco, 8 May 2020.

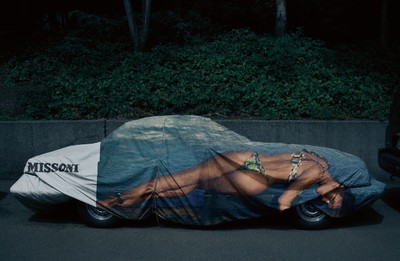

Thomas Lenthal: Tell me about your portfolio. I was really impressed with the production value of it; I have no idea how you pulled that off. Who took the pictures at night, and where are they?

Giovanni Bianco: When you asked me to do something, I didn’t know what I was going to do. I’m not a photographer; I hate taking photos. If you saw my pictures in my iPhone, you’d cry. But I’m a very good research guy. So I took the easy option! I made all the image references about parking; I’m fascinated by parking. When I was young, my dad sold fruit, and I worked with him for 14 years, selling fruit in the street while going to school. We lived in this beautiful, but modest house in Santa Teresa, a neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro, and we had a parking space, which my dad rented from other people in the area. He had this little space for parking his car. All my life, I’ve been fascinated by parking. I’m not crazy about cars; I don’t drive anymore. Cars are not my passion, but I really love parking. I worked with Steven Klein for many years and he loved parking, too. I thought: everything that is happening in my life right now is parked: my work is parked; my life is parked. Everything is parked. So I thought I would select some jobs and clients that I really like and park them with me. When I started as an art director, I was in packaging design, and I loved the idea of packaging. Before the idea of packaging the cars, I had the idea of creating a supermarket. I thought, ‘I’ll buy supermarket packaging and I’ll put on labels with my clients.’ That was too complicated, so I thought instead about parking cars, and when my guys did the first image in Photoshop, I loved it. I hope you like it, because it’s a weird idea.

Thomas: Yes, but I love the notion of you dressing the cars, because those big pieces of cloth are like dresses.

Giovanni: Yes, it’s a dress. Because when you don’t use the car, you protect it.

Thomas: Here’s the first question: do you think restriction is useful or necessary when it comes to creative work?

Giovanni: All my life, my whole career, I’ve worked with restriction – it’s a good challenge. The photographer I’ve collaborated with most is Steven Klein. He is the most challenging man in the world. He’s very hard. He’s an intense guy; he challenges you all the time. When I started to collaborate with him, he pushed me to do different types of research. It was always painful, never easy. I started out with the idea that everything that is complicated is good; you need hard work, and I believe in hard work. I work with a lot of passion, and it’s a challenge all the time, so I think restriction is normal. I’ve worked with Madonna for 16 years, and she’s the most demanding woman in the world. She’ll look at what you’ve done and say, ‘Do you like that?’ And you’ll say, I like it, of course, and she’ll say, ‘Make it better.’ That’s normal for me. Sometimes, if a client loves the work from the beginning, it makes me doubt what I’ve done. I think, ‘Oh, that’s too easy.’

Thomas: You talk about the hardship of doing things. That’s interesting, because none of the other art directors addressed the issue of it sometimes being painful.

Giovanni: For me, it being painful is part of the process. It makes you grow. I am learning something all the time. Of course, it’s better, it’s nicer if you’re doing something easier. But I like the idea of working hard and challenging yourself: I want it to make it better. That’s been the same all my life. Nothing in my life has been easy: I don’t come from a rich family; I have a million problems; I have dyslexia; I come from another country. It’s different for me. My career is not easy.

Thomas: It’s fighting, fighting.

Giovanni: I have to fight for everything. I’m not part of the mafia. I’m on the outside. I’m not part of any gang. It’s a unique way of working. All my career I’ve had to fight for everything. It’s normal for me.

Thomas: That’s super interesting. Looking back, was there a defining image, reference, person or moment from your teenage years that made you want to be in fashion, be a creative director?

Giovanni: That is so funny, because when I arrived in Milan I hated fashion. In Brazil, I had studied engineering at university and thought that would be my life. But I loved painting. At the beginning of my career, I started doing graphic design for galleries, for furniture designs, for logos, for packaging; fashion was something I was completely uninterested in. When I was 21, I didn’t know the difference between Armani and Versace. For me, it was all the same. It’s so weird, I never once thought about working in fashion, even for a day. I really wanted to work in the arts; I’m a frustrated painter. I love furniture design. I love working with type, logos, packaging. I thought, ‘What’s fashion? It’s just clothes.’ One day, when I was in Milan, I met Domenico and Stefano, and they invited me to work for Dolce & Gabbana. That was my first job in fashion. When I discovered this world, I thought it was amazing. I loved the photos; I loved the research. And then I discovered Fabien Baron: he is my hero. I started working with him, and I discovered Italian Vogue, and I was fascinated. Over one or two years, I looked at all the fashion magazines, designers and all fashion photographers. I was fascinated because it was so new for me. I started to look at CD covers, too, at advertising for Calvin Klein, and I thought, ‘Wow, this is my business.’ That was my beginning.

‘When I was 21, fashion was something I was completely uninterested in. I didn’t know the difference between Armani and Versace.’

Thomas: How old were you when the Dolce Gabbana thing happened?

Giovanni: I was 27. It was late. I met Stefano and Domenico in Milan, at a party. We started talking, they asked me what I was doing, I said I was a graphic designer and they said they needed someone for D&G, the second line. They asked if I was interested. I said yes, but I’d never worked in fashion, and they said, ‘You’re the perfect guy. We want someone who doesn’t work in fashion for this job.’ I did the first catalogue for D&G, the first advertising.

Thomas: Who was the photographer?

Giovanni: Paolo Leone. He’s a friend of Domenico’s, a Sicilian guy. I remember he did the first advertising with Stella Tennant. That was my beginning. All my references are Fabien: I looked at him, and thought, ‘I want to be him.’

Thomas: Was Fabien the person you most admired in the fashion industry?

Giovanni: Yes, but I didn’t know any others! Afterwards, I discovered Marc Ascoli and many others.

Thomas: What about today? Who is your hero in the fashion industry?

Giovanni: I still think Fabien is one of the best. I think the digital world has changed a lot, but I think our generation is still doing the most classic and beautiful work: you, Marc Ascoli, David James. We have so many good people in this business. But Fabien Baron is still doing classic, elegant work, and good ideas come from the classic. The digital world has changed things a lot. There are young guys doing such nice work, but I can’t think of one idea that stands out.

Thomas: What’s most intuitive in your work and what is stuff that you tend to overthink?

Giovanni: My best skill is research. I have 9,000 books; I collect books. I have an incredible collection of images. If you talk with the photographers that I work with – Inez [van Lamsweerde], Steven, Marcus [Piggott] – they’ll tell you the same: my most powerful thing is research. I’m very good at it. I think my weakness and where I could do better is typography. I care so much about ideas and concepts. Sometimes when I’m doing typography I feel that I’m old-fashioned.

Thomas: What makes a good fashion image?

Giovanni: When you have a good team, good clothes, good hair, good makeup, a good environment, a good idea, a good model, and quality. What’s happening today with images: it’s fresh, it’s nice, but I miss the quality. It’s so fast today; everyone can do everything on their fucking mobile, everybody’s a photographer. It’s amazing – I love democracy – but I miss quality. I miss looking at a picture and thinking, ‘Look at that light! Look at the quality of the light, the make-up, the clothes.’ With Joe McKenna, you see the quality of the clothes; you don’t need to Photoshop the clothes. I’m so happy that I started out 30 years ago and worked with people who have a real eye for quality. When they do photos, you don’t need to use Photoshop to repair anything. Today, you get so lazy because you know you can do it in Photoshop. When you work with a good team, everything is amazing.

Thomas: So the quality of the ingredients is what makes a great fashion image.

Giovanni: Yes: quality people and a quality idea. You need an idea. One of the reasons I lost interest in doing magazines is because every month you needed to do three or four editorials, and it’s impossible; after three years, it’s impossible to have a good idea every month. You need 3 million years every week, because the next week you’re doing another magazine. That’s hard for me. I’m old-school. I don’t believe young photographers develop their own language in a year. Some people started yesterday, and now they are a big star; I don’t believe it. For you to have direction in your trade you need to take at least 10 years, to develop your own language.

‘Who cares about realism? Our job is to make dreams, fantasy. That’s why I love to work with Steven Klein; he’s a master of fantasy.’

Thomas: Tell me – as you’re talking about stuff that’s difficult – have you had a fashion disappointment and what did you learn from it?

Giovanni: It’s the deadlines. Today, everything is for tomorrow, and you don’t have time. It’s sad. Most of the time the clients want quantity, not quality. They don’t care about quality ideas. The most important thing you are doing is delivering. It’s a supermarket. This is a disappointment. I still believe in quality and the idea and that one good image is more important than 20 stupid images.

Thomas: So you’re disappointed with the current state of the industry?

Giovanni: Yes. When I look at advertising or editorial, I don’t know what brand they are for any more. Sometimes, I put my hand over the logo and I can’t tell which brand I’m looking at. For me, there is no longer any distinction between them, between what is luxury, what is not. I don’t know any more. I think brands have lost their DNA. Everything is so fast: there’s so much quantity, there are pre-collections, fall, winter, summer. So many.

Thomas: Do you think that the sheer amount has created confusion and is reducing quality?

Giovanni: No one can have that many good ideas. It’s ridiculous. I remember doing six images for one advert, and now you need to do 30 in one day. How can you create good images when you have to do 30? It’s a catalogue.

Thomas: We were lucky to work back in the late 20th century, when we had a lot of time to create.

Giovanni: Today, when I work, I respect the time frame, I respect the budget, and I will adapt for the client. No problem. But if you ask me what I believe, that’s something else. I believe in quality, but I need to work, so I adapt. If the client wants 30 images in one day, I do 30 images in one day. But it’s so hard to have quality like that. It’s impossible.

Thomas: It’s very difficult. If you’re doing 30 images a day for advertising, you don’t have time to…

Giovanni: Reflect! And now you need to do picture and video together. How can you do that? You do it, but you can forget about quality. But I need to work, and I respect my clients and they don’t have much budget, so they need that. If you don’t do it, some young people will do 30 images and a video in a day for $5,000. And people will say, ‘Bye-bye, old man.’

Thomas: Do you prefer to work for a very niche audience, or to appeal to a wider audience?

Giovanni: A wider one, of course. If I have to work for 10 people, I’ll work for 10 people, and the work will be more personal. What gives me the most pleasure, though, is working for a brand. I love a challenge, and a big brand is a great challenge. You need to talk to everybody, not just the elite. A small audience is easier; the challenge for me is talking to different people, different countries. You need to sell to every different kind of mind; it’s amazing. Your challenge is to make something universal.

Thomas: And when you have to please someone like Steven Klein, it’s as difficult as pleasing 10 million people sometimes, isn’t it?

Giovanni: I love working with Steven Klein, because he is a genius, one of the greatest photographers in the world. I love working with geniuses; I don’t care if it’s harder, because a good job is hard. If you work with a genius you know you’re going to produce something good. I look back at the work I did with Steven, and I still think it is some of the best I’ve done. That, for me, is a pleasure. Steven is a genius. Same with Steven Meisel. Some photographers you work with, you never forget the the resulting image, because of the quality. It doesn’t matter that it was harder. For me, it’s a pleasure.

Thomas: Tell me something about what is happening right now. When all this goes back to normality, do you think you will be more interested in fantasy or realism?

Giovanni: I really don’t care about realism any more; I hope it will be fantasy. People need to dream. I want to dream. Realism is a nightmare: oh my God, it’s so boring. Who cares about realism? Our job is to make dreams, fantasy. That’s why I love to work with Steven Klein; he’s a master of fantasy. You create history; you challenge yourself. It’s not something you’re going to forget the next day. Every day I talk with him; I miss working with him.

Thomas: Tell me about him, because you seem enthralled by him. What do you appreciate? The narrative?

Giovanni: The narrative, but also that he drives you crazy. He makes you challenge yourself more and more and more. He loves fantasy. I like that. I love working with Mert and Marcus, with Inez and Vinoodh; I like working with different photographers in different ways. But Steven challenged me so much, that’s what I appreciate with him. Every time I work with him, I grow. I’m so tired afterwards, but I’m so happy when I see the result and I know it’s good.

‘I remember doing six images for one advert, and now you need to do 30 in a day. How can you create good images like this? It’s a catalogue.’

Thomas: When this whole episode of confinement is over, is there something that will change in your way of looking and doing things?

Giovanni: Things are going to change a lot, because we need to change our way of communicating. The approach that we have with clients, with the audience, is going to be completely different. In Brazil at the moment, if you talk to people about sales, or the brand, people are in shock, because there are more urgent things to talk about, like food, people dying. People need to communicate more about human beings, saving lives, social things like that. Of course, every culture is different, and with each client it’s going to be different. I hope that this generic thing is going to end. I must say that I’ve been really disappointed with brands in our business over the past few years. This break could offer everyone an opportunity to have more personality and quality at each brand, to create more of an identity again. Everything has become more generic.

Thomas: Do you think that’s because everything became so huge? What happened?

Giovanni: Everything got so big. It’s all the same. I really don’t know, but my feeling is that when you look at something now it’s really hard to understand which photographer shot the advertising, which one shot this editorial? Everything is too similar. Sometimes old photographers try to be young, and they’re doing some trendy image and it’s so confusing. We really need more personality. I remember when you would look at Yamamoto and know it was Yamamoto; when you’d see Comme des Garçons and know it was Comme des Garçons; see Prada and know it was Prada. Today, you just don’t know – everything is too similar.

Thomas: You think the solution is to go back to being unique?

Giovanni: I think so. People need to create stronger identities, more personality and not be super generic. I hope so, or I’m going to do another job! I hope I can have clients who are interested in doing something interesting. It’s going to be a good lesson for people, that they need to think a lot about responsibility, about what they’re doing. We’re not going back to the same thing. We have learned a lot. We have more respect; we have more social responsibility. I hope we come back as better human beings.

Thomas: How does that fit in with your idea that essentially we’re in the business of making frivolity for people? That we want to make people escape and dream. Yet you are saying we need to be more socially aware, and so on. Aren’t these two things…

Giovanni: It’s different. In editorial life, I think we need more escape, more dreaming, more ideas. While each brand needs to respect its core identity. If you’re not a dreamy brand, of course you shouldn’t do that with your advertising. I hope that people respect their DNA more, their identity. Every brand has become more generic; people are afraid because they don’t have good sales, so people are doing safer images. I feel that at all the brands, all the marketing is using the same formula. That’s tired. I miss good ideas and good advertising, but I also believe in communicating with responsibility, because the world is going to change. But how can you know?

Thomas: Everyone has a different take. Everyone is projecting their own positivity or negativity.

Giovanni: I’m super positive that we’re going back better. I’m Brazilian, and I have this idea that life can always get better. I believe in music and sound and colour. I believe that we have the opportunity to change and do better. That’s why I believe in fantasy, because people need something more.