In early April, we sent the following request to a broad range of fashion designers.

Given the current situation, we would like System’s next issue to focus on long-form interviews led by designers – conversations recorded via video conferencing.

Now feels like a particularly relevant moment to focus on designers, as the industry looks to you to lead fashion towards the future, to capture the moment, and, perhaps above all, to enable us to dream.

What would you talk about? It’s not for us to dictate this, because we feel the project could have an inherent Warholian quality – anything that you say becomes valid when placed in the time-capsule context of this document of the moment.

Many wrote back, saying they’d like to use the opportunity to connect with a friend, a colleague, a confidant, a hero, or another designer.

We’re extremely grateful that they did. And the least we could do to return the gesture is give each their own System cover.

Photographs by Juergen Teller

Creative partner, Dovile Drizyte

In early April, we sent the following request to a broad range of fashion designers.

Given the current situation, we would like System’s next issue to focus on long-form interviews led by designers – conversations recorded via video conferencing.

Now feels like a particularly relevant moment to focus on designers, as the industry looks to you to lead fashion towards the future, to capture the moment, and, perhaps above all, to enable us to dream.

What would you talk about? It’s not for us to dictate this, because we feel the project could have an inherent Warholian quality – anything that you say becomes valid when placed in the time-capsule context of this document

of the moment.

Many wrote back, saying they’d like to use the opportunity to connect with a friend, a colleague, a confidant, a hero, or another designer.

We’re extremely grateful that they did. And the least we could do to return the gesture is give each their own System cover.

‘Life will be quieter for at least

a year and a half.’

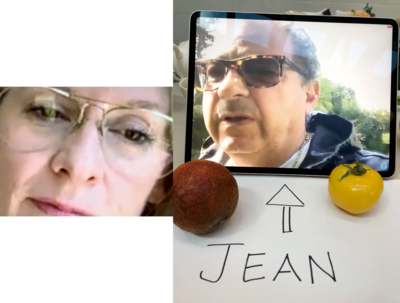

Jean Touitou and Suzanne Koller in

conversation, 16 April 2020.

Moderated by Thomas Lenthal.

Thomas Lenthal: I’d like to start with a very obvious observation: we belong to an industry in which everyone laments that they don’t have time to do what they want to do, yet now we find ourselves in a situation where we have time on our hands. What changes might this situation bring about in the way you think about the future?

Jean Touitou: You’re right; you often hear complaints in our milieu to the effect that we don’t have enough time to get everything done. There are structural reasons for this and I can tell you what they are straight away with the aid of a biblical reference: it’s all down to the merchants in the Temple. They are the commercial directors in the fashion houses who wait until the very last minute to issue their recommendations and guidelines, which then place design studios in dire straits. Without them, we would have enough time to work at a reasonable pace. On the other hand, those same commercial directors are the reason that all the fashion houses haven’t gone under right now. Actually, we don’t really have any spare time on our hands. On the contrary, the disruption caused by this pandemic has reduced our time. You have to imagine, Thomas, what it’s like for Judith [Touitou, artistic director of A.P.C.] to coordinate the pre-autumn 2021 collection away from her studio, away from the sources of her fabrics, away from everything. That forces you to be ultra-busy the whole day. In fact, once the phase of disbelief was over, we entered into a phase not unlike the Le Mans 24-hour race: a never-ending sprint to the finish line, just to survive. When everything grinds to a halt, when you are on a huge ship and there are holes everywhere, you don’t have the time to ask yourself, ‘Am I going to plug the holes with cork or with plastic?’ No one has time for anything at all. In a lot of companies, not just our own, so many people are burning out. I know that a lot of people managed to escape to the countryside, but you just have to imagine the hours that they are working, with video conferences until 8pm and kids and the need to put meals on the table. It’s not a relaxing time, at all. The situation has the effect of massively compressing time.

Suzanne Koller: It depends: if you are a freelancer, like me, you have a lot of free time. Even if everything has just ground to a halt…

Jean: You don’t have an infrastructure to uphold. It’s really the infrastructure that’s the issue.

Suzanne: Exactly. And to circle back to your question about time, I am not at all bored, and the extra time I have on my hands is actually opening up new avenues for me. I mean, I’m the kind of person who responds quite well to adversity – I’m a fighter, more or less – and this current situation gives me time to reflect, to talk with the magazines I work with, and really think about how we could do things differently. When I look around me, of course, I have man friends like Jean and Judith who are in the process of setting out contingency plan A, B, C or D, according to whether we will reopen in June, July, September, or indeed next year, and I have the impression that this juggling of scenarios is exhausting for all of them. At magazines, I think we’re reacting to the situation by thinking about how we can communicate differently. In my case – and this is something I don’t dare mention to those people who are burning out – this time has allowed me to observe and to devise new ideas. In any case, I really think that I was completely saturated before this began, and I’m sure I’m not the only one. That’s why I really do appreciate this period of standby for the time that it affords me to think about what comes next. It doesn’t panic me at all.

Thomas: This is the least reflective time of all, Jean,because you have a business to run.

Jean: Yes. I am in the process of writing an internal memo about how normal business might resume. Particularly the fact that we’ll be going on fewer business trips, so we will have a quieter life for at least a year and a half – the effects of what we’re experiencing are going to last that long. There will be fewer of us in meetings; there will be fewer photo shoots with 15 people. Generally speaking, we’ll all have to do everything in a kind of minimalist way, which will probably result in more time to spare.

Suzanne: We don’t really have a choice. We’re simply going to have to start out again slowly. The restart will have to be really gradual.

‘When you’re on a huge ship and there are holes everywhere, you don’t have time to ask yourself, ‘Am I going to plug the holes with cork or with plastic?’’

Jean: Not to labour the point, but this slow pace is itself going to require an incredible amount of energy. In any type of physical activity, if you do a movement properly and at the normal speed, and then try to repeat it slowly, it takes a ridiculous amount of concentration. It will take the same kind of effort to resume business slowly, what with the security conditions and everything else. I don’t believe for a second that this crisis will have the benefit of de-stressing the fashion industry, because so many people find themselves with such difficult issues on their hands. Ultimately, and this is, unfortunately, not very poetic, it all boils down to four letters in English: R.E.N.T. I say this because the union of landlords the world over may be informal, but it is terribly rigid, and this is very much the wall that towers over us. All the magazines in the world – Vogue, BoF – can wax lyrical about a better world in the future, with more time, better integration, more sustainability, and the like. We can say as many enlightened things as we like about how the future will look, and how we would like it to be. But at the end of the day, the central issue remains how to deal with all these landlords. It’s paradoxical: we have the luxury of talking about principles and sharing really intelligent ideas, but the stark reality of the matter is that the rent needs to be paid. In our case, we have 50 leases on our stores. How do businesses pay the rent to maintain their physical presence? Believe you me, that’s an unsolvable question.

Thomas: Everyone is uneasy and fright-ened, but if certain landlords do turn around and say, ‘Mr Touitou, it was nice knowing you’, it’s not like there’s anyone to take your place straight away.

Jean: That’s more easily said than done. When you are confronted with 50 legal departments from 50 landlords, you really have to be quite stoic. It takes a lot to say, ‘I’m not scared, bring it on.’ I am obsessed by an image of the 1929 crash. Thomas, as a very visual person, you must know all of the photos from that period of the people who were on the road, ordinary people who had lost their jobs and were on the road in search of work elsewhere. We can’t take it for granted that we’ll get anywhere with the big landlords because – and I’m sorry about this, but we do have to touch on economics – they are most often investment funds, and it’s those very same funds that, alongside insurers, lend money to states. They know perfectly well that governments at the moment are going to place themselves in risky situations, which doesn’t encourage them to relent and lower their guard at the other end of the spectrum. It’s really something that everyone in the fashion industry is facing right now, even the biggest brands. Some good news is that all of those people – buyers, journalists – who came to Paris six times a year, and went to London six times a year and Milan six times a year, will have had a break. They were all physically worn out; just a glance at them was enough to know that. No offence, but honestly, you only had to look at faces of the people in the front row. What I’m talking about is denial. Everyone in the front row at fashion shows looked like they were about to collapse. Everyone put their best foot forward with their clothes and hairstyle, but you still got the feeling that they were about to drop from exhaustion.

Suzanne: On that, we agree.

Jean: If it’s possible to talk about benefits in this initial phase of the crisis then most definitely it will be the fact that there will be less travel and, for the moment at least, no more fashion shows. It will take the whole thing down a notch. Unfortunately, the fundamentals of the luxury industry are that human beings need signs that distinguish them, status symbols, signs of wealth. It’s precisely these outward signs that they purchase from luxury brands. In principle, that’s just human nature, so it stands to reason that the luxury industry will restart, and that, unfortunately, sets the rhythm for the fashion industry. I’m not trying to be pessimistic, but I just don’t see how things will truly change, with this wonderful exception of less travel. I can’t imagine the large corporations saying to themselves, ‘Well, we were producing too many bags, so let’s start making clothes again, and, you know what, let’s make them reasonably priced.’ I just don’t see it happening.

Suzanne: No. In the meantime, perhaps we’ll at least see fewer fashion shows or fewer collections, because it’s my impression that we’d reached a veritable saturation point, both for consumers and for creatives, with the number of collections. If you worked with creatives, with the artistic directors of fashion houses, you realized that everyone was simply overloaded to the point of no longer knowing why or for whom they were designing. Was it for consumers or their own marketing directors?

‘We have 50 leases on our A.P.C. stores. How do businesses pay the rent to maintain their physical presence? Believe me, that’s an unsolvable question.’

Jean: I don’t think you can criticize all marketing directors as, again, it’s thanks to them that you no longer have to be haunted by the fear of poor sales figures. You no longer have to think, ‘Oh my God, if I mess up two seasons I’m over.’ We rely on the judgement of these individuals who tell you, ‘This is too creative’ or ‘You have to bring in some T-shirts with the logo because that’s what pays the rent.’ There are all sorts of absurd rules. Sweatshirts, for instance. We told Suzanne about this and she didn’t want to believe it, but the minute you place a little triangle here [pointing to his chest], your sales drop by 40%. It’s hard science and you shouldn’t mock it, as thanks to these MDs, you can no longer fail spectacularly. In a way, we manage things just like Madonna, who releases a hit every year thanks to marketing. There’s another image that I’m thinking about at the moment: it’s Odysseus with his ears stopped with wax to avoid being seduced by the sirens and so shipwrecked. At what point do we in the studios say, ‘OK, listen guys, you’re all geniuses, but if we keep listening to you, then we are going to jeopardize our future.’ So we plug our ears, we tie ourselves to the mast and we stop listening to the sirens. That’s the balance that we’re looking to strike between creativity and production. [Laughs]

Suzanne: My viewpoint comes more from the creative side, though I understand the commercial aspects of the business and the importance of factoriing them in. And what I find, Jean, to be something of a shame is that the commercial side now overrides everything else. We see a lot of fashion houses where the requirements from the marketing departments are very clear: the right skirt length, the use of certain colours, trousers, et cetera. You have to tick boxes, which doesn’t sit at all well with creatives. They try and their work ends up on the runway, but then you never see it in stores. I completely understand what you say about finding the balance, yet I still think that it’s a shame that anything that is a touch more imaginative falls by the wayside. Working on more fanciful designs would allow these creatives to build their talent and foster their creativity, but if we keep offering the same product every season because it was a bestseller from the previous season, we will kill that creative soul that you can still find at fashion shows, but only find in small quantities in stores, if at all. Gradually, the voice of reason from marketing departments has completely taken over the creative. Currently, many fashion houses are complaining that their garments aren’t selling anymore, and it’s because customers are bored stiff with what’s on offer. It’s no longer interesting. For the past three or four seasons, we have been seeing the same fashion shows on repeat at most of the fashion houses. I understand your point, and I agree with you, but a little more creativity wouldn’t hurt. What would be the harm in trying out a few eccentricities here and there? They could even make some sales, if only by accident.

Jean: [Laughing] You’re right, I know, I know. But…

Suzanne: Just imagine you have a fluorescent-pink item that turns out to be an unexpected hit in the shops and you tell yourself, ‘Damn, we didn’t stock enough of those. We’re out of luck because they’re selling like hot cakes.’

Jean: To illustrate Suzanne’s point, take the example of Bottega Veneta with their last season, six or eight months ago. They put bags on the market that didn’t tick any of the boxes prescribed by the marketing doctors. I mean, everything has a special name; it’s like in American psychiatry, they discover new symptoms all the time. There was the cross-shoulder thingy, a bag for the first date, a bag to pay the mistress in Hong Kong. You know, at Louis Vuitton, there was a format of bag for Hong Kong businessmen who have a mistress on the mainland.

Suzanne: Come on, really…?

Jean: Really! I’m not making this up. [Laughs] The bag that is expensive, but not as expensive as the bag you give your wife. To get back to the point, it just so happens that Bottega released these bags that didn’t tick any of the boxes and sold really well; so well that they sold out. So, it can happen, it really can happen, but those occasions are few and far between, unfortunately. I know it might not look like it, but it frustrates me just as much as anyone else. Sometimes I also dream up creative ideas and look at them through the commercial lens, and it’s not even the commercial department, it’s Judith herself who tells me, ‘Drop it, it will never work.’

Suzanne: Why though? Surely, you can treat yourself to one or two eccentricities a season? Or do you put on the marketing glasses straight away each time and just let it drop. I mean, you’re the boss after all.

‘Designers have been overloaded to the point of no longer knowing why or for whom they’re designing. For consumers or their own marketing directors?’

Jean: I let it drop, because I am cynical and I end up telling myself, ‘OK, she’s right, just drop it.’

Suzanne: Even for one or two eccentricities? I don’t know, I just think it could be worth…

Jean: The grip that marketing has on fashion houses is what’s making fashion boring. It’s almost like a drug. The CEOs of the large brands are like drug users, in a way. They have found a type of heroin with zero physical side effects. The only side effect is that they are less creative, and in order to settle their debt with the conscience of their creatives, they gift him or her a fashion show: ‘Here you go, my dear. Let loose! You can do as you please!’ They buy his or her conscience that way, so the designer isn’t too ashamed of themselves.

Suzanne: But don’t you think that at some point, something can become unhinged in the mind of an artistic director of a fashion house who realizes the disconnect in designing for no valid reason. The clothes don’t end up anywhere. The best form of recognition is when people want to wear your clothes.

Jean: And that’s precisely how their psychoanalysts make their fortune. The creatives just have to attend a few sessions: ‘What am I doing with my life? I have good ideas, I’m good at my job, but my skills aren’t used. I’m just part of the decoration…’

Suzanne: It’s like being the costume designer for a play that’s only performed once…

Jean: This type of idea would never go out on a mainstream platform. You could never speak your mind freely to the general public about the isolating loneliness of fashion designers when confronted with the mega-trusts for whom they work, because that very same mega-trust is fascinated by profit. It’s as if they get a rush after a sniff of heroin. The figures go from 300 million to 500 million. What a rush! And then they set their sights on the 1 billion mark and are elated because maybe they can reach 1 billion. Set against that backdrop, the creatives pale into insignificance.

Thomas: Jean, if I understand correctly, you’ve always sought to keep a sense of proportion in terms of your firm’s growth, always tried to keep it at a ‘humanly accessible’ scale, right? That’s very appealing as the antithesis of the prevailing ideology within the fashion world today, where everyone wants to reach the 10 billion mark. It’s the new Wild West. You’ve never indulged in that particular form of hubris, although you could have easily taken that path. I’m not doing a character analysis, but your case is fascinating as there aren’t many out there like you.

Jean: Restraint… But we have still amassed a certain size. When you’re faced with paying the leases for 84 stores and points of sale, you find yourself saying, ‘I’m not that small after all.’ We’re far from a billion, but that still leaves you quite a large ship to sail. I would never want to become too massive. I mean, it’s not something that would give me any particular satisfaction. You know, when I was young and revolutionary, I was very much influenced by a sentence from Lenin. It was in an article in Pravda in March 1923, before he pushed forward with his new economic policy, at a time when he realized that his dogmatic model wasn’t really working. The sentence refers to the development of the state apparatus, and it is about the only thing that I kept of Marxism in the end. In French, the sentence is: Mieux vaut moins, mais mieux. [Better fewer, but better.] I’ve always known that keeping the focus on the qualitative aspect would allow us to stay in the game. In fact, this crisis has left us on our knees, but due to our organization, we’ve not collapsed to the ground. A lot of people are completely floored; they’ve had the rug completely pulled from beneath them. In my case, we already have the prototypes for Spring/Summer 2021, which will be presented at the online fashion week in June, but I have counterparts who have not even produced their prototypes for summer 2021.

Thomas: And who will go under.

Jean: Yes. I’m pretty sure there are going to be lots of companies who do. It’s possible. Not the big corporations, but the small and medium-sized ones.

Thomas: I have a question for you, Suzanne, which relates to A.P.C., too, in terms of aesthetic philosophy. You often employ the terms, ‘the new normal’ and ‘the new simplicity’. But neither term corresponds to what you were saying earlier about why we don’t see unconventional, experimental, creative fashion. Is there a paradox there?

Suzanne: I don’t think so, because ‘the new normal’ can mean everything and anything; it’s just what’s become the new standard at the time. As for ‘the new simplicity’, it’s quite similar. What I meant before, when I was talking about creativity, doesn’t necessarily mean extravagance, which doesn’t really correspond to my tastes. My point about creativity was about not being stuck on repeat and, in relation to marketing, not always reproducing the item you made the previous season, just two centimetres longer and in a different colour. It’s true that I use ‘new simplicity’ often, but it’s a term I used a lot before the crisis because I had reached a kind of overload of too much of everything. In terms of fashion and fashion imagery, I wanted to move towards more simplicity, more minimalism and classicism. Everything seemed to have reached a point where people in fashion found everything distasteful, but just continued as usual as they didn’t know what other option they had. And there was this desire to move away from all of that and towards the more classical values of simplicity and normality, as they were the values that we were missing. I think that these months of quarantine have really given us an appreciation of the simple things that we should cherish. At least to begin with – and this echoes what Jean was saying before – we’re going to move towards safe bets. I’m not talking about the shows, because they have become 10-minute entertainment spectacles that don’t correspond to the notion of simplicity or normality because they no longer have any true meaning.

‘A.P.C. is far from a billion, but that still leaves you a big ship to sail. I’d never want to become too massive. It’s not something that would give me satisfaction.’

Jean: We have shared an analysis of that situation for some time now, but can we imagine an industry that would forego staging them? Do you sincerely believe that might change?

Suzanne: No, probably not. But they’ll probably have to suspend the usual routine for at least six months. There won’t be any shows in September, but perhaps this will bring about new ways of working. There will be a general need for everyone to devise new ways of presenting their garments.

Jean: Ultimately, the old ways will return one day. Someone’s bound to suggest staging a show on a cruise to Kyoto or something, and it will start again just as before. It’s like Doctor Strangelove…

Suzanne: But they won’t have any more money, will they? I mean, they won’t have a spare 10 million to ship everyone across the world to the location. Don’t you think? You need serious resources for that kind of exercise, and I just don’t know if they will still have that kind of money.

Jean: The large groups will still have the means to pull it off, that’s for sure.

Thomas: Take the infamous example, the one everyone was talking about, even on the evening news, when Hermès reopened its store in Guangzhou. The shop took €2.5 million in one day. People jumped at the chance to become consumers again. I personally didn’t think people would change their habits, and in that instance it was plain to see that they hadn’t. I doubt that the big corporations will question their methods for presenting and publicizing products once the wave has passed. I don’t see why things would change, despite the fact that we have all realized the absurdity of the status quo. It’s paradoxical: the shows are put on for an audience that isn’t the final consumer, so what is their point? The shows are actually pretty unimpressive once they’ve been photographed or filmed with an iPhone. Despite all the resources and staging that are pumped into them, they are only really impressive when you’re actually there.

Suzanne: Those live transmissions are so unimpressive; they’re done purely by default. They set up a live transmission for the sake of it, but no one has really taken the time to think it through properly. No one has actually sat down to imagine how it could be effective onscreen. In fact, if you were to stage a show – a fashion show or any kind of show – specifically to be filmed for social media, it would have to be conceived completely differently and then might not be as effective for the people actually there. In theory, I think there are two distinct ways of proceeding. It’s a subject still to be examined.

Jean: Now’s the time to come up with a superb idea for how to do it.

Suzanne: That’s not the only issue. The problem that I’ve noticed often, and which is a real blind spot, is acting. No one seems to give it any thought, but the models don’t know how to act. Thomas, I imagine you have found yourself in situations like this at times, where a photo shoot is followed by filmed footage. It’s not the models’ fault, but they don’t know how to act and they’re not directed properly. That’s why it ends up looking totally cheesy and the films we produce feel cheap. It’s true! You’re in stitches laughing, but no one knows how to direct them! The photographers don’t know how to direct the models; they know how to give them directions for a photo shoot, but not for action or movement. I often advise models to take acting lessons. It’s a skill that they’ll need. Everyone is taking photos, yet films get the most views on Instagram and social media, much more than photos.

‘The best-known models are almost like silent-era actresses. They manage to give off something surprising just by being themselves.’

Thomas: I’ve been saying it for a while and it’s curious that huge brands with their unlimited resources haven’t made forays into film. If you spend tens of millions on a show, you could make a really beautiful film for the same amount. It’s not rocket science. Remember when the big brands decided to get involved in architecture. They said to themselves, ‘Who are the big-name architects? We’ll give them a call and set things in motion.’ It was no more complicated than that. If you belong to a big house, there’s nothing preventing you from redirecting your budget towards films in order to present products.

Jean: What you describe is more or less possible with architecture, but literature, cinema, poetry – all the major artforms – require a kind of magic that money can’t buy.

Thomas: Surely, you could call up, for example, Lars von Trier and say, ‘Can you make a film for me?’

Jean: Yes, but he’s going to be prejudiced against you. Not you, personally, but you know what I mean. He could easily decide, ‘I’m not going to prostitute myself. I’m going to take the money and run.’ The problem is also that they would never give the director carte blanche. The problem is that at some point in the filming, someone is going to insist, ‘The bag has to be in the shot.’

Suzanne: But that’s exactly what already happens with product placement in films. Take James Bond, for instance; it’s a massive exercise in advertising.

Jean: James Bond is different; James Bond is God.

Suzanne: Sure, but the films contain loads of product placement! And it’s more than noticeable. He’s God, so perhaps the product placement isn’t such a big deal. Saying, ‘The bag needs to be in the shot’, is not that different.

Jean: OK, so perhaps we can make a little film where we tell Jean-Luc Godard, ‘The bag has to be in the shot.’ We’ll see.

Suzanne: Excellent! I’ve just had a great idea, Jean, for a film with a bag. I’ll tell you about it later, but it’s a great idea!

Thomas: It’s actually really refreshing that out of nowhere, in response to a question, we can imagine solutions that could make our way of working much more interesting. I find that really intellectually stimulating.

Suzanne: Yes, when we have time to actually think about it properly. I pity all those people who are overwhelmed with Zoom calls, WhatsApp messages, constant meetings. It’s got to be tough. I find that difficult situations, with limitations and little money, are often when we are most creative. In any case, when we have too many resources at our disposal, too much freedom and free rein, I’m not sure that as creatives, we’re on our best form.

Jean: It’s true. To give you an example from our brand. I consider that the future should actually be a mixture of incredible high tech, with all the impressive features available in virtual format, and the 19th century. So for the virtual fashion week in June, we’re going to cut the fabrics used in the collection into small swatches to emulate the swatch boards used in 19th-century mail-order fashion catalogues. These swatch boards will be sent to each of our 350 wholesale clients and I’ll include a handwritten note in an envelope with a personalized wax seal.

Thomas: You know they also used to send dolls. You could to do that, too.

Jean: Ah yes, the dolls to display the different looks.

Suzanne: No – really?

Thomas: Yes, in the 19th century, representatives of the large couturiers would travel to the European courts with suitcases filled with little dolls.

Suzanne: Barbie dolls?

Thomas: Any kind of doll. Given the time available, perhaps they would be Barbie dolls, but it’s up to you.

Jean: A Wes Anderson animated film, for example.

Suzanne: Yeah, with Barbie dolls.

Brilliant. Dressed in A.P.C. Can you imagine?

Jean: A.P.C. and Barbies: that’s quite a marriage!

Suzanne: Jean is noting it down.

Jean: I was just tidying my papers!

Suzanne: I have a question for you both. You’ve already partly answered it, but do you really think that everyone will want to jump back on to the consumerist bandwagon at the end of lockdown? Do you want to become a consumer again?

Jean: Personally, I want to become a consumer of what I left in my wardrobe in Paris and haven’t been able to wear. I don’t have a never-ending stock of clothes with me here in the countryside. I’m even in the process of cutting up garments to make some shorts. I might even make some djellabas in wool canvas as evening wear. In my case, Suzanne, I don’t think I’m a good example; I’m not a big consumer.

‘Instead of runway shows, in the 19th century, reps of the big couturiers would travel to the European courts with suitcases filled with little dolls.’

Thomas: I’m not at all a consumer of fashion; I’m a consumer of clothes, of course, but that’s different. And you, Suzanne?

Suzanne: No, not really. It scares me, in fact. At the moment, I get my kicks by just going to the pharmacy and buying toothpaste and deodorant. As the days and weeks have gone by, I have the impression that there are certain things that no longer have the same importance. It’s a weird feeling. It’s the sensation that something has deflated; fallen flat, in fact. That being said, I don’t think my consumption was exactly opulent, either.

Jean: Let’s be honest, Suzanne, and it’s not a criticism, but you are an excellent consumer. You embody the fashion industry’s saving grace. I say that with no irony whatsoever. When I see you sauntering towards me with a new bag, I know instinctively that you have spotted the right bag to have at that point in time.

Suzanne: That’s part and parcel of my work. Jean, perhaps you’re misreading me a bit. I have to have the right bag because my job is precisely to give you the impression that, ‘Suzanne’s got the right bag; she has good taste and she’s someone that I need to work with.’ My clothes are my window display.

Jean: Absolutely. When I see Judith arriving with more packages, I don’t say anything, but she can tell by my demeanour that I am surprised, and then she tells me calmly, ‘Jean, this is my job, and if I lose interest in clothes, it wouldn’t make sense anymore…’

Thomas: So, Suzanne, are you saying that you’ve lost interest in that at the moment? As it’s linked to your profession, which is somewhat on hold, you no longer need it as much as before?

Suzanne: Perhaps, yes. But another question I’ve been thinking about is what are we going to want to show the world in our fashion shoots after this? What kind of images are people going to want to look at?

Jean: It’s a valid question. For example, at the moment, I have an e-mail account called ‘press’ where I receive all my publications, and I really can’t bring myself to open it. It’s as if that belongs to the world before. That was before and what’s going to be the new representation of fashion now? For me, it’s a blank page.

Thomas: Which circles back to what we were saying earlier, do you actually believe that there will be a before and an after?

Suzanne: I think we’re already in the after, Thomas. The situation won’t be as it was before – we’re already in the after without fully realizing or comprehending it yet. The after is the here and now. Not the lockdown itself, but all the rest: protecting yourself; the fear of catching the virus; the fear that you might contaminate someone close to you; the wearing of masks; physical distancing. We’re already living in the after.

Jean: Perhaps the solution is to work with actors, even for photo shoots, not even for films, as they will convey an idea or a sensation in the photo. Perhaps that’s what was missing: an emotion that wasn’t being acted out with all of these exquisite photos with exquisite models in exquisite hotels. In the end, you sometimes still had the impression that the model was a call girl who didn’t know what the hell she was doing there. Perhaps it’s time we rethink and reimagine a format where the emotion is palpable on the model’s face and facial expression.

Suzanne: I agree with you. Once again, it’s a question that was needling me before all of this, but what does fashion photography mean today? In the sense that, in the past, fashion photography consisted of catalogue images so that women could keep abreast of what was going to be in fashion. It was all about catalogues, in fact. Nowadays I don’t know a single woman who leafs through photo shoots for the same reason. No one looks at photo shoots to choose the fashion they’ll buy; it just doesn’t happen that way. I’m sabotaging my own job, but it’s time we reinvented it because it no longer makes sense. The women I know all follow Instagram influencers and who is wearing what and what they want to buy. That’s what they’re looking at. So for those fashion photos in hotel rooms and such like, I’m not at all sure that the woman of today desires that dream, or wants to project herself into that type of image. The images we were producing before were already part of the past, yet we were still caught in it. Didn’t you have that impression?

‘In my view, fashion has become much more of a B2B network, to use the popular term; a profession that today involves tens of thousands of people.’

Thomas: I had the impression that we were relishing irony, which is always a guilty pleasure but a pleasure all the same. In my view, we’ve become much more of a B2B network, to use the popular term; a profession that today involves tens of thousands of people.

Suzanne: Well said.

Thomas: The profession, the fashion industry, has now grown to be who-knows-how-many hundreds of thousands of people, and within this mix, they have all become ‘little experts’ about one another. It’s almost like film lovers or something, where everyone is a know-it-all. We now have all these really young people who are ‘specialists’ of a fashion culture that starts roughly in the mid-1990s, and from then on, they know it all. They understand and are genuinely interested in all the meta-discourses about fashion. They keep up with the fashion community – the new model here, the new fad there – and the entire who’s who of fashion in a photo shoot: ‘Oh yes, she’s still a big make-up artist; he’s still the hairdresser of such and such; she is on the cover of this and that.’ All these preoccupations that 20 years ago were limited to the profession have mutated into a more general culture that has been widely ‘democratized’.

Jean: Yes, we’ve all become pandemic specialists.

Thomas: We’re all fashionologists!

Jean: It has indeed become a globalized conversation with 200,000 to 300,000 participants, some of whom have begun to utter a lot of platitudes. We can imagine that about a third of these individuals will lose their jobs. Take, for instance, the whole fashion community in New York, with all those totally useless fashion shows: all those brands from the kids of such and such family who went to Saint Martins and then organized a fashion show in New York that daddy wrote all the cheques for. All those utterly useless brands and the parasitic audience that goes with them will come to an end. Yet we don’t know in which direction we’re moving; we don’t know what fashion imagery will look like, except that we’ll have to have something much more substantial to convey with our images, and that’s why I agree so much with the concept of using actors.

Thomas: You’re both a little harsh with the profession. After all, you both contribute to varying degrees to adventures in fashion photography that are by no means crap. Suzanne, it’s not as if you only have brain-dead-looking models in your shoots… I find you both quite harsh because when fashion photography is amazing – which an infinitesimal fraction of it is – it is no less moving than other art forms. I don’t think that fashion photography, when it’s well done, is doing that badly.

Suzanne: The intention wasn’t to be harsh for the sake of it. I like to question myself and my work; I think it makes me progress. What I wanted to express was the sensation of overload that I experienced before the pandemic, and how I’ve questioned myself about how to take my work to a different place and a different level. In the end, the pandemic has provided me and others with the opportunity to rethink how we work, how to inspire emotion through a photograph made with the aid of a computer or to direct a model or an actor. These are the aspects of the situation that I find most fascinating and challenging. I didn’t want to be negative, in any case.

Thomas: I find your self-questioning extremely inspiring. I love being negative, by the way, but it seems to me that the best-known models, those who manage to stay in the game for a long time, are almost like silent-era actresses. They manage to give off something surprising just by being themselves. It’s like a strange skill they have. The big-name models quite often know how to act well. The problem today is that we’re talking about 16-year-old girls…

Suzanne: Exactly. It’s not their fault. They’re not even around for five years and have no time to grow at all. Thomas: It’s not a question of skills; it’s simply a question of maturity, which makes the whole issue extremely delicate. Anyway, this has been really interesting.

Thomas: Discussing all these subjects is really inspiring.

Jean: So, Thomas, what are you making for lunch?