17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘I’m already onto the next thing

before I’ve finished what

I’m doing right now.’

A conversation with

Lee Swillingham, 6 May 2020.

Thomas Lenthal: The portfolio is immensely good fun, and I should thank Sølve [Sundsbø] for participating. He’s really a whizz. Can you give me a bit of background on how you put it together?

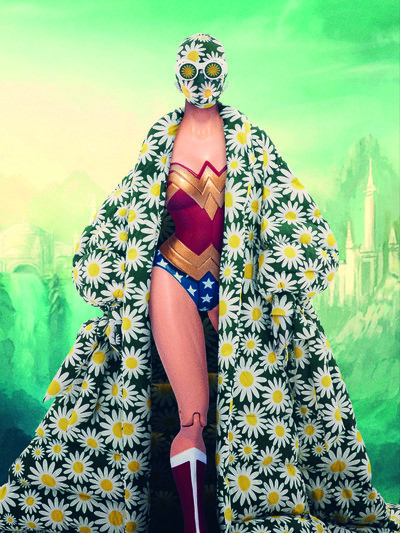

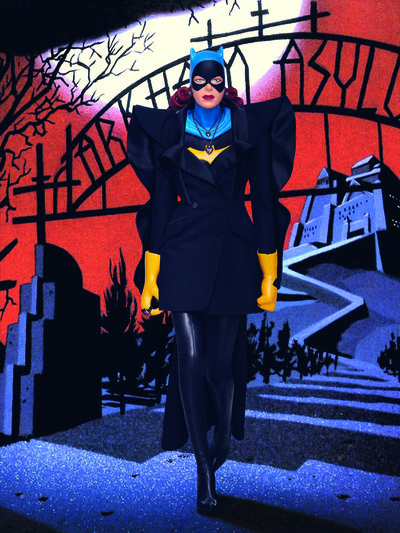

Lee: I’ve been stuck in my little office at home, which is where I am now, since just before the British lockdown started, a good seven weeks ago. So when you came to me with this project, it seemed like a good challenge. I always enjoy coming up with amusing solu-tions, probably because I’ve been doing this for a while, like you, and there isn’t always much opportunity for humour in what we do. Although, in recent years, I guess it’s become more typical for there to be some humour in fashion, which is one of the more interesting innovations. When you look at what Demna [Gvasalia] does, for example, there’s always some kind of humour there. Anyway, I’ve been collecting American comic books since I was about 12, and I really love French comic books, so I just had this idea: what if I use these guys as the models? I thought that was funny, and I called Sølve straight away and he thought it was a great idea. Then we got to work in this entirely legal lockdown way, where no one came near anyone else. I left all the action figures in a box at the end of my street – a very chic box, actually – and Sølve picked it up and we went about doing the shoot. It actually took quite a long time. This is the first time I’ve worked in such a long-distance kind of way, even if Sølve is only a mile or so away. It was a very interesting process and procedure, even just from a purely organizational perspective. The figures include one really tiny old Star Wars action figure; the detail that Sølve got out of that little face is incredible. And that’s Cyclops from the X-Men. Gro [Curtis] picked out the fashion and did a great job finding good clothes for Darth Vader to wear, and I love Rick Owens on Batman. He looks pretty good. It was just a really fun job. I mean, what was interesting was watching Sølve and the retouching, how they really adapted the clothes from the press photography and managed to change the shape to fit the bodies of the characters. Batman is a very bulky guy, so they changed the Rick Owens silhouette and put it on his body so it looks a lot more muscular than it would on the catwalk. Everyone really got into it. It’s fair to say that people have a lot more time on their hands at the moment; photographers certainly do because there are no shoots. I’m guessing that your project has probably kept a lot of people busy, which is good; they’re probably quite grateful.

Thomas: People jumped on the opportunity!

Lee: It was fun. It took quite a long time, probably longer than I thought it would, but that’s because Sølve wanted to do a really amazing job retouching and finalizing the images. And, as I said, some of these figures were tiny, like Chewbacca. Some of them were really big, like the really beautiful Batman that I bought in New York 10 years ago. The way they shot it was fantastic, and I’m really pleased that it’s really fun.

Thomas: It looks good. What about the backgrounds? Did you take care of that yourself? Or was that Sølve?

Lee: The backgrounds were basically sourced online and only slightly manipulated and changed. With the Madman character, the guy wearing the white suit, I actually know the creator, so he drew that background and sent it to me. That’s a slightly less-known character, but still a really great American comic book character.

Thomas: Your portfolio is very you. It reminds me of the approach, attitude and take on the industry that The Face had back when you art directed it. I wasn’t aware of it, but a whole generation of younger English art directors reference The Face as some kind of teenage epiphany, something that drew them into this profession. I wasn’t expecting that. It was a major influence on a whole generation of British art directors, specifically that notion of giving fashion a narrative. That’s not something we necessarily do on the continent.

Lee: You just made me think of something that hadn’t occurred to me before. You were doing magazines around the same time that I was doing The Face, and if you remember, back then you weren’t given an infinite amount of pages for things you were working on. A story would be 6, 8, 12 pages if you were lucky, 14 hardly ever. Since then, I’ve worked on projects where the number of pages for a story seems to be infinite, to the point that it’s really not an edited story, but instead a portfolio of what happened to be shot that day. I think that’s a very different mindset. Clearly, the restriction of having a certain number of pages focuses not only the stylist and photographer and the people on the magazine, but everyone trying to tell that message, whatever it is.

‘I’d struggle to find much of interest in fashion images that were just simple studio shoots recording a look. I almost couldn’t see the point of them.’

Thomas: It’s true that page inflation within portfolios has become mind-boggling. Some are 100 pages long! That’s a fairly recent development. I wonder whether it’s not a way for some photographers to stake out their territory?

Lee: There’s a lot going on and that could be part of it. Also, since digital became the default way that people make their work, you can produce more content. That applies to everything, not just fashion photography. We both worked with [Jean-Baptiste] Mondino, didn’t we? He’s incredible, and if you think about the amount of thought and effort and energy that went into everything he did. That was 6 or 8 pages; that was not 32 pages, 40 pages, you know?

Thomas: It’s as if paper is trying to mimic the digital world. We’ve been slowly driven into this inflation, and like greedy children, we went for it. I remember a great photographer who said back in the 1990s: ‘Photographers should probably only take about five pictures a year.’ And now he’s producing, like, 1,500. Is restriction itself useful to creative work?

Lee: I thought about that very point when I was working on this. I think it is, absolutely: it confines a creative space, and it gives parameters. Don’t you?

Thomas: Absolutely. I couldn’t even imagine where to start if I didn’t have some kind of ironclad context. That’s immensely helpful, because you’re essentially trying to find a solution, but you’re still trying to infuse some kind of grace into the whole thing. Next question: what do you think constitutes a good fashion image? Has this definition changed during your career? I realize that that’s a huge question!

Lee: I always like fashion images that encapsulate something more than just being a record of the clothes. In the early days of my career, I always struggled to find much of interest in fashion images that were just simple studio shoots celebrating or recording a particular look. I almost couldn’t see the point of them. Obviously, you learn more about the industry and realize why they are always needed to some extent. But I think good fashion photography reflects the culture of the times, the zeitgeist, the politics.

Thomas: It’s funny, because certain creative directors are like, ‘a great fashion image is timeless’, which strikes me as a strange proposition.

Lee: I would completely disagree with that. For me, they’re like a strand of pop culture, and I think good pop culture has a disposable aspect to it. I don’t think we should be trying to create something that focuses on whether it is going to be in a museum in 30 years. I don’t see how you can do that and make an interesting and relevant image. I’ve never been that interested in the idea of fashion photography in a reverent museum space. I love art, and I love art photography, but I see them as slightly separate things. There have been amazing retrospectives of various fashion photographers, and I’m not saying they don’t belong in a museum space; I’m just speaking about my personal interest.

Thomas: You’re more interested in the vernacular for fashion photography?

Lee: I think so. Thinking about The Face, which I haven’t for a while, it wasn’t technically meant to be a fashion magazine. It was a culture magazine that had fashion imagery in it. I just saw fashion as one of the strands of pop culture, along with the music, the art and other culture elements. That’s probably why you see a link between what I’ve done in this portfolio and what I did back then; I think that’s completely legitimate. When Lara Croft and Tomb Raider was a big cultural thing in the 1990s, we did the same thing; we took Lara and got the gaming company to dress her. You know, it’s funny: looking back at some of those labels: it was Helmut Lang, which doesn’t really exist anymore; Jean Colonna, which I think is gone; McQueen was in there and did a great thing.

Thomas: Were you at The Face when Stéphane Sednaoui’s fashion superheroes series came out?

Lee: No, but I’ve stolen the title. That was before my time. I was in high school when it came out and it blew my mind when I saw it at the newsagents. I thought it was the most incredible thing ever. It made me want to go and live in Paris. The fashion innovators in Paris in the 1980s, especially Jean Paul Gaultier, took fashion and slammed it into pop culture. It just blew my mind.

‘Good fashion photography is like a strand of pop culture, and I think all good pop culture has a disposable aspect to it.’

Thomas: You mentioned Jean-Baptiste and I mentioned Stéphane. They are two image-makers who were heavily involved in music, which gave them an interesting bridge into a career in the UK, and at The Face. The most interesting work came out in British magazines.

Lee: The most fun I had at The Face was Mondino calling me out of the blue with some crazy idea. I mean, he did that gangster fashion shoot in LA in the super high-key colour, with young people on cars brandishing chrome weapons, wearing Hawaiian shirts. Baz Luhrmann and his wife told me to my face that the whole art direction for Romeo+Juliet came directly from that shoot.

Thomas: Was there a defining image, reference, person, moment from your teenage years that was instrumental in you moving towards a career in fashion or in a particular creative direction? Two other British creative directors told me it was The Face. Not to say that it was The Face for you…

Lee: It was The Face, when Neville Brody was art director, and there were those incredible covers, like the cover that was just yellow, with the big, bold word ‘ELECTRO’ on it. Sure, it was The Face. I probably wasn’t so much aware of the photographers, but I was probably aware of the styling, what Ray Petri was doing, and the graphics. Apart from that, I was looking at old Nova magazines that my mum had, because she was a graphic designer. Nova was designed by David Hillman, who was a great editorial designer. That magazine looked incredible. Helmut Newton shot for Nova, so I became aware of his images very early on. I loved his early work because I loved movies, and he would shoot stories, like this amazing James Bond-style shoot with a cool guy in a suit and a girl by the door. It was before his famous style developed, I guess.

Thomas: There was a big trend for that in fashion magazines. Even in French Vogue you’d have funny stories. Even Guy Bourdin would do some of those, and they would ask Helmut for stories. Oddly enough, I have issues of French Vogue from the mid-1960s and you find Superman in there. The vernacular was very important to creative directors back then.

Lee: I discovered French Vogue when I was at Saint Martins in the late 1980s, early 1990s, and that blew my mind. When you discover those things.

Thomas: From the 1970s? You’re talking about the Guy Bourdin stuff?

Lee: All that stuff. Guy Bourdin, all that amazing stuff. And it was just on another level, really. Just incredible, incredible stuff. Also, I loved Chris von Wangenheim for the slightly more Studio 54 vibe; his pictures were incredible. It was funny discovering that stuff in England in the late 1980s, because there was quite a strong politically correct movement among young people. I would buy these second-hand Helmut Newton books from the early 1980s and have them in my desk at Saint Martins and I’d get remarks like, ‘Why have you got this disgusting pornography?’ So then I just kept them at home, because I was embarrassed. Obviously, that whole aesthetic then went on to be one of the biggest influences on the whole fashion industry for the next 20 years.

Thomas: Thanks to Tom Ford.

Lee: Yes, exactly.

Thomas: Can you give me an example of what is most intuitive in your work and what you tend to overthink?

Lee: The answer is one and the same. I have always enjoyed doing the layout of a fashion story from early on in my career, because you’re creating narrative, contrast and juxtaposition. I think art directors are much better at doing this stuff than photographers.

Thomas: There are some photographers who aren’t that bad at it, but you’re right.

Lee: On the whole, a good layout is invariably probably done by an art director. I do those quite quickly and intuitively, and I enjoy doing them, and I’m quite pleased with the results. But in this digital age, when things sit in the ether, on the server, and other people on the magazine see them, and people start doing the credits, it goes round this process and it lives for too long, and then you see it again and you’re, like, ‘Should I make a change?’ Or someone else suggests a change, or you’ll try a different version. You can end up with so many different ones, and you always go back to the original. It’s a bit like things never seeming to end nowadays. They get tweaked and adjusted to the very last moment, and if it’s a digital project, then even when they get uploaded, they get tweaked again. Kanye West released an album a couple of years ago, the album got put on Spotify and iTunes, and then a week later, he changed it and put up a new version. That’s what life is now.

‘I would have old Helmut Newton books in my desk at Saint Martins and I’d get remarks like, ‘Why have you got all this disgusting pornography?’’

Thomas: That makes sense: the liquid creative object. Did you always strive to be different and individual from a young age? Was that a preoccupation of yours?

Lee: When I was young, yes. I grew up in Manchester and being interested in music and clubs and fashion. There’s a lot of individual expression in that. I went to a boy’s school where you had to wear a uniform and a tie, so when you went out, you wanted to express yourself and feel different. I always wanted to be involved in graphic design and magazines or film and music. Today, in the work I do with Stuart [Spalding] at Suburbia, we like things to change all the time. We like new stuff and we don’t really look back. We’re always trying to make something look different. We like pop culture; we like music; we like pop art; comic books are a big influence. One of the best inventions for me is Spotify; it’s unbelievable, because I love music and I love the recommendations. I’ve discovered so much amazing stuff based on what the algorithm tells me. And most of my friends and people I know go back to their comfort records and music when they’re listening. They’re listening to The Verve or something from when they were a kid in the 1980s, or Fleetwood Mac or Tears for Fears, while I’m listening to the new Weeknd album. I love new music; I love grime. That’s why I think The Face was the perfect magazine for me. I mean, I’m already onto the next thing before I’ve finished what I’m doing right now. That’s just the way my mind works.

Thomas: Do you prefer your work to appeal to a more niche and in-the-know demographic, or a wider audience?

Lee: When I was doing The Face, some issues, the publisher would come in and announce to everyone, ‘Amazing news, guys! Last issue we sold 250,000 copies, globally!’ And everyone would be really happy. But nowadays on Instagram, people have half a million, a million, 2 million. I mean, the whole audience thing has changed so much that I don’t even know how to answer that question. When we were working on Love with Katie [Grand], we knew that a cross-section of people who looked at that magazine were fashion students, fashion industry people, and public consumers specialized in their interests. So we were geared towards them, but there’s also a pleasure and enjoyment in taking to a more mass market some of your expertise, your influences and the things you enjoy in your more niche work. I feel a real sense of achievement when I get something over the line, as they say, and manage to do something that looks more interesting than what a client normally does. One thing I learned, way after I left The Face, was the need to try to understand what would be a good result for the client, rather than trying to talk them into something that might not even be right for them, just because you and the photographer have decided it would be a cool thing to do. I probably used to do that, but now I find it really interesting on a traditional advertising level: what’s good for the client, what can give them a good result, and if you can use some of your expertise and experience to achieve that result, then I think that’s really satisfying. In all of the bigger brand stuff I’ve worked on, in the grand scheme of things, did anyone realize or notice it?

Thomas: That’s more interesting than essentially talking to your peers?

Lee: It satisfies different parts of the brain. Maybe there’s more of a conversation when you’re talking to your peers, more of a creative exchange going on. It’s definitely different parts of my brain, and it’s definitely satisfying different aspects. I’m truly enjoying myself when I talk about these old magazine projects, and now we’re working on British Vogue, it’s about how we can bring some of our look and feel from our other magazine projects to Vogue. It will be interesting if you ask me this question in six months or a year because that is the brief: to change the way it looks and bring some of that look and feel, but completely mindful of the fact that British Vogue is a very successful Vogue magazine within the marketplace.

Thomas: Which person working within the fashion industry do you most admire and why?

Lee: Perhaps it’s not a very original answer for an art director, but I love Alexey Brodovitch.

Thomas: So far, you’re the first to say Brodovitch.

Lee: No way! When I discovered his work, I was, like, ‘Oh yeah, well, this guy’s got it. He’s figured it all out. He’s got all the answers. I don’t need to look any further.’ The answers are just there. It’s incredible, really. All my influences are art directors: like Henry Wolf, the other American art director. I love all those old Esquire and Vogue and Bazaar. I loved magazines when I was growing up. I was super passionate about them.

‘I’ve learned to understand what would be good for the client, rather than doing something the photographer and I think would be cool.’

Thomas: Words and images together.

Lee: Exactly.

Thomas: What does success look like for you?

Lee: Just being creatively satisfied is a massive part of that. It’s nice to connect and communicate with people. Working on The Face, you definitely felt you were having a conversation with the readers, and that was before you could literally speak to them. I mean, now you can really speak to people. But we felt that back then. There’s still nothing more exciting than to have an idea and work with a team of people to make it come to life. I feel that with this portfolio I’ve just done with Sølve. I could see the thing in my head and was wondering, ‘Could we make that happen? Could that come to life?’ And then I second-guessed myself the next day: ‘No, that’s stupid and crazy.’ And then I came back to it a few hours later: ‘No, it’s great, let’s do it!’ I like that process. It’s also nice when clients are happy with the work you’ve done for them – I should say that as well!

Thomas: Describe a professional disappointment and what it taught you.

Lee: I suppose early on in my career when I was doing The Face – I keep talking about The Face, which isn’t something I intended to do – I started getting work on advertising projects. I didn’t really care that about it, because I was just enjoying doing The Face and this was just extra money. There were a few shoots in Paris or Milan when me and the photographer thought we were doing a great job, but the client complained or really didn’t like the picture. I later realized what we were doing: we were still trying to make images for The Face, rather than trying to create pictures for the client. At the time, I didn’t give a shit. I was young and arrogant, and I didn’t care that they were upset. Looking back, I had to go through that, but I wasn’t doing such a great job!

Thomas: You disappointed your client, but you didn’t…

Lee: What was disappointing to me? I can’t think of anything! My memory is so fragmented. There’s sure to be something we tried to do that fell apart. Obviously, I’ve forgotten about it.

Thomas: As things gradually return to some level of normality, will your impulse be to explore notions of fantasy and escapism or will you be more inclined to double down on realism and documenting the moment?

Lee: That’s a really good question. What’s interesting about working on a magazine that has a regular schedule, like Vogue, is that we’re having to think about that almost every day, because at least two issues are going to be published during the lockdown. I guess the question is: will the pandemic cause some kind of cultural shift? It’s got to, right? It’s just got to. I think it will affect everything. Do you think the shows are going to survive?

Thomas: Whether the shows survive or not, the biggest issue is not, in my opinion, how they look, it’s how you transcribe them. There’s a complete lack of talent in reformatting the thing and making it a cinematic experience.

Lee: Do you still go to them?

Thomas: Sometimes, and they can be quite exciting if you don’t go all the time. You know as well as I do that there’s a nicheness and such a weird atmosphere. It’s so tense, so bizarre, so odd; it’s like nothing else in the world, really. Do you go?

Lee: I went to a few in Paris last season just for Vogue. I didn’t mind dipping in and out; I couldn’t do the whole week. Nothing really changes. I still had some cheeky older lady or someone from some obscure fashion magazine trying to steal my seat. So, nothing really changes, but I was there as an observer. I was just quite interested to see that the dynamic hasn’t really changed that much. A good fashion show is like being at a good rock show or something.

Thomas: I’m not debating the merits of the spectacle when you’re at the show, I’m just wondering why no one thought it might be a good idea to make it exciting to watch if you’re not there.

Lee: With the way the world has been accelerated through the pandemic, and everyone is doing video conferences like we are now, it just seems that all these big communal events are really going to have to justify themselves. People are always going to go watch a football match, but I wonder if the logistics of doing fashion shows are going to keep making sense.

‘I guess the question is: will the pandemic cause some kind of cultural shift? It’s got to, right? It’s just got to. I think it will affect everything.’

Thomas: Honestly, I’m not quite sure what purpose they still serve.

Lee: When you see the stills or the films, it often just looks like ever-younger models looking quite bored. You just don’t get any feeling at all.

Thomas: Like they’ve completely lost interest. There’s an interesting commercial space for creative directors to figure out a way to literally put that together, to work on how to make a film out of it. Are you itching to get back to pre-Covid-19 processes? The ability to say, ‘OK, I’ll go to New York and shoot with Steven Meisel and Pat McGrath.’

Lee: The travel thing is going to be messed up for so long. I don’t personally miss travelling a lot, but I’m sure I will in a few months, because it just keeps things interesting.

Thomas: And lastly: do you think it’s possible to be truly unique today, and does that even matter?

Lee: Yes and yes: it’s possible to be unique and it does matter. There are still people making original music, films, photographs, graphics, magazines. When something good and new comes along, you look at it and go, ‘Oh, that’s really obvious, why did no one do it before?’ Your magazine was a new thing that didn’t exist, but it now feels very much part of the furniture, right? You did it. You came up with something new, and it’s important.