In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘We can hardly criticize image over-

consumption when we work for a

weekly magazine that produces 50

times the content of a biannual.’

A conversation with Lolita Jacobs

and Jean-Baptiste Talbourdet-

Napoleone (LJBTN),

13 May 2020.

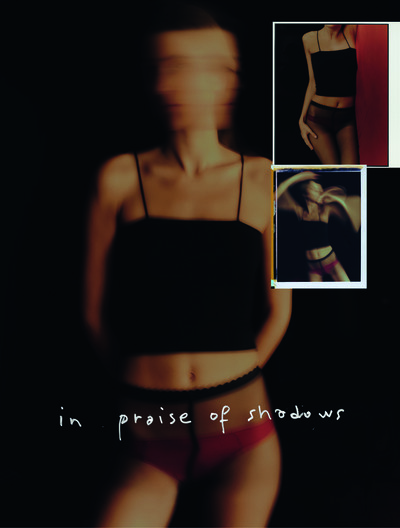

Thomas Lenthal: Let’s start by discussing your portfolio. You’re among the rare contributors to have exploited the notion of intimacy in the simplest and most direct sense of the word. If I understand correctly, these are your own clothes, and you’ve concentrated on exploring what can be intimate, familiar, and even domestic. It’s very nice work: simple and direct.

Lolita Jacobs: We tried to do what we could with what we had!

Jean-Baptiste Talbourdet-Napoleone: We asked ourselves a series of questions. Were we working just as ‘artistic directors’? Because if so, should we commission a photographer, and so on? Was it in the end completely our project or were we just graphic designers? Should we do it ourselves, as we like doing, using several of the strings to our design bow, from photography to fashion design, and even take it further, with Lolita as the model? Could we develop an ecosystem that could produce the whole series? The brief was ‘fashion portfolio’, so we wondered whether we wanted to do one in a ‘pure fashion’ version, without being too literal. We like fashion, but we also like to step away from it. We were trying to do something more artistic, with a focus on clothes. But which clothes? That’s when we embarked on the idea of intimacy, which includes us, too, as we’re intimately together, as well as being confined together; we quickly realized we had to do it ourselves, play the game. All this questioning was pretty interesting.

Thomas: I’ve asked everyone this question, and everyone has answered yes, while understanding the question differently: do you think restriction is a useful or even necessary thing when it comes to creative work?

Jean-Baptiste: If we had no restrictions, we’d be artists, not artistic directors, and I mean artists in the noblest sense of the term. Restriction is necessary, sometimes, because you need a framework and a brief. But it can be complicated to negotiate, too, because sometimes you just want to blow up the framework.

Lolita: Restriction is interesting, because if we didn’t have parameters, we wouldn’t have a space in which to play, test, push, have fun. At the same time, it’s exciting to be able to escape those parameters a little.

Thomas: I’d like to come back to this notion of the artist. Over the past century, artists have been people who impose their own restrictions. Even if that is just the medium that they choose to work in. I’m interested in the notion of external restriction. I don’t know about you, but I’ve never received a brief that holds water in my life.

Jean-Baptiste: In that situation, the restriction is the client. But ‘restriction’ doesn’t necessarily mean something pejorative. With every client, the first thing we do is try to ask them the right question. Clients will tell us lots of stuff, and it’s important to absorb all that and then to go back and ask the question: ‘I think this is what you want, is this right?’ That’s the first thing. In reality, the restriction is going to come from the client’s understanding, from whether they are open enough to go where we would like to take them, from whether they trust us or limit us. Perhaps they want something and it’s clear that there is no chance of taking them in another direction. In general, I’d say that the restriction is usually the client.

Thomas: Which brings us to the subject of how you talk to clients. Some interviewees have said that if they can’t communicate clearly with the client, they can’t do the work.

Lolita: That’s also something that comes with experience and depends on how much stature you have.

Jean-Baptiste: Some younger people work like that, too. There are people who work in absolutes and ideals – and I really admire that. That’s not how we do things; we’re more inclined to keep trying to work it out to the very end.

Lolita: Sometimes, we have to force ourselves a little! But it’s cushioned as we’re two: If one of us feels less comfortable than the other, then we can have a back-and-forth that can be useful.

Jean-Baptiste: Sometimes we can start with a really ambitious concept and the work is about peeling back the layers, even if you almost never get to the essence of the idea.

Lolita: You’re exaggerating! It does happen sometimes.

‘It’s cushioned as we’re two: if one of us feels less comfortable than the other, then we can have a back-and-forth that can be useful.’

Jean-Baptiste: Rarely! These days it’s only magazines that offer that kind of total creative freedom.

Thomas: What, for you, is a good fashion image?

Jean-Baptiste: I often hear photographers describing themselves as fashion photographers. I really don’t like that, because to me you’re either a photographer or you’re not. If you’re a good photographer, you can shoot anything: food, landscape, reportage, fashion. A fashion image is interesting precisely because fashion has constraints. It is only good if the team and limitations work together: the model, the styling, the hair, the make-up, the ideas, the photographer, the lighting. It’s a group effort. Not that you necessarily need all those elements to produce a good image. On a shoot, the two crucial roles are model and photographer. In the 1990s, you had Kate Moss shot by Corinne Day on a white background, no lighting, no styling, just Kate Moss in her pants on a white backdrop – and it became an iconic fashion image. The necessary elements are the model and the magic of the photographer. It’s also about the fact that it takes place at a particular moment in time, because a fashion image is totally connected to its society or era. Whenever I think of a period in history, I think of its clothes and cars. When I think of the 1960s, I picture the clothes people were wearing and the cars they were driving. A fashion image is of its time and its social context.

Thomas: The notion of a document of a specific moment is a funny one because it sets aside ideas of nostalgia. There’s a whole part of Meisel’s work, for example, that is about a moment, but is also about escapism and dreams. It seems to me that this escapism is one of the schools of fashion photography, but it’s condemned by serious people who can’t stand frivolity.

Jean-Baptiste: I know this is very reductive, but I’ve always thought that there are two categories of photographer: the Steven Meisels and the Juergen Tellers. The Meisels are going to be sublime; they have a particular magnifying touch and they know how to do everything: black-and-white, colour, daylight, flash, studio. Then there are the Tellers who are not at all about magnifying reality, but who rather shoot, like Andreas Gursky, almost brutally, to produce a raw reality. I always wonder which way to go with a project: should we magnify or portray reality?

Thomas: As a result of what we’re living through, which side are you going to want to explore afterwards?

Lolita: If you look at the work we did for the portfolio, we’re not at all about reflecting reality, we are focused on something much more aesthetic. We’re not always like that, but I do think that the aesthetic aspect drives our work more than straight-up reality.

Jean-Baptiste: I’d like to see our work in the studio and for the magazine in the Steven Meisel category in terms of artistic direction. I oscillate between styles and I like to mix things up; I don’t want to always do the same thing. This was an aesthetically driven project, and as soon as we’d sent it, I thought we should have done something rawer, trashier, in the kitchen with the baby, more reportage style. But if we’d done that, I’d have wanted to do something else.

Lolita: We just gravitated to what felt natural in the moment.

Jean-Baptiste: It’s true that we do definitely tend to gravitate towards the aesthetic impulse. I wonder, for an artistic director, if it’s legible to have several styles or if it’s more interesting to have a single style for 30 years, as some art directors do. It’s great to never tire of something like that, to bang your nails into the same hole with the same hammer, again and again. And there are others who are guided by the era. I like to live in my era, to talk to people of my era, to live in and deal with the present. That’s something that’s been rattling around in my brain. I’ve been trying to figure out whether it’s better to stay on one trajectory or whether you can afford to deviate, knowing that you’re still heading in the right direction.

Thomas: Was there a moment or image that inspired you to choose this particular line of work?

Lolita: Jean-Baptiste and I got here by different routes. I studied art in Britain and that education system is very different: it’s much freer and self-taught. You’re left the freedom to think and reveal your ideas. After I’d finished that, I really wanted to go into fashion, either design or styling, so I did as many internships as I could, working in magazines, with stylists. Because of that, and because of who I met, I developed an artistic trajectory. I met Franck Durand, who became my mentor. I started working in his atelier and discovered this career that I had been working towards for years without having a name for it.

‘As soon as we’d sent you our portfolio, I felt we should have done something rawer, trashier, in the kitchen with our baby, more reportage style.’

Jean-Baptiste: It was a bit like that for me, but very different from the point of view of education. Even if Lolita says she had a free learning experience at Saint Martins, it was still academic, in the sense that it was four years of study and Saint Martins is considered the best school for fashion and design. So, even if you are free, there are professors to push you.

Lolita: But it was really an art-school education; you were supposed to become an artist at the end; you had to figure it out yourself. The name Saint Martins is impressive, but the reality is that we were left to our own devices.

Jean-Baptiste: Yes, but you had teachers, you had the time to explore, to experiment, you had materials at your disposal. I did a year at Ateliers de Sèvres, then a year of graphic design school, but I left at 19 because the school wasn’t for me. I had to learn on the job, and I didn’t really discover graphic design until I ended up in an advertising agency doing layouts. What I really wanted to do, though, was animation at Pixar or Disney, when I discovered while working that drawing was my absolute passion. Then I met Antoine Jean and Éric Pillault of Éditions Jalou and Jalouse, and that’s how I became familiar with the idea of the magazine as an object and with typography, which I’d found totally tedious at school. I discovered fashion much later, when I was 19 or 20; it hit me, and I was hooked. I discovered a world I knew nothing about. I had to learn everything myself; I bought magazines. I had no teachers to guide me, no peers to discuss things with. Antoine pushed me to buy magazines and to pay attention to who the photographers were, who the stylists were. He pushed me to buy photography books, to drown myself in imagery. So Lolita and I had different trajectories, but for both of us, the self-taught aspect was important and still is. The portfolio reflects that, too. My father, who was in the military, always told me that you have to set an example. I apply that to my work; if I want to talk to a photographer or stylist or illustrator, I have to understand what they do so I can talk to them properly. As artistic directors, having that kind of knowledge helps us communicate better with the people we work with. If you ask a photographer to do something and he or she says, ‘that’s nonsense’, then you have to know what you’re talking about or you’ll get nowhere. If I can tell the photographer to stand in a certain place, to use a particular lighting, to use one aperture rather than another, or a particular lens, the photo will be closer to what I had in mind. Of course, there are ways of asking, but being able to do that diplomatically means I can get the result I want, at least on commercial jobs. With magazines, it’s much freer and more about curation than artistic direction. It’s about selecting the right team, putting people together, letting them get on with it, and not intervening. I can always readjust if what is emerging isn’t in the creative spirit of the magazine, but the principal idea is not to be too present.

Thomas: Ideally, do you prefer to work for a niche audience who you respect or for the general public?

Jean-Baptiste: These days, the spectrum is so wide, we couldn’t say that we’re working for a niche audience.

Lolita: I prefer a wider audience, even if it’s interesting to address our peers.

Jean-Baptiste: The idea of a wider audience is interesting. With M le magazine, we’re talking to everyone from my grandmother in deepest Périgord to our peers in the sixth arrondissement of Paris. It’s about being able to talk to the widest number of people, but educating them, too, in a sense, in what we love, our tastes, graphic design, and photography. When we do a photographic portrait of a politician, we’re not going to do it how [weekly news magazine] Le Point or [daily newspaper] Le Parisien would do it, using a cheap digital news image and no retouching. We want to speak to the widest audience without compromising on quality. In our studio work, we don’t tend to limit ourselves to a particular type of client. We prefer to be open-minded and to work with all sorts of brands, with their different goals. That way we can really have fun and not get stuck doing the same thing. It’s interesting to have a wider perspective, even if there are niche jobs that interest us, too.

Lolita: I agree, but whether it’s niche or a wider audience, you still have to deal with people who speak the same language. Even if the views are different, they should have the energy and the desire to create.

‘People think artistic directors direct teams, which means being strong, and they don’t think women can do that type of role – which is completely wrong.’

Thomas: It’s stunning when commercial work also has complexity and poetry. I always think of Hollywood studio cinema from the 1930s to the 1950s. The restrictions were appalling, but it produced films for a huge audience and managed to create some of the greatest moments of poetry of the 20th century. There are artistic directors who manage to achieve that too, but it’s rare.

Jean-Baptiste: It’s rare to have those two things together and to make a success of both. Today, we have somewhat lost the concept of beauty, which is of course subjective. Standardization has taken over France, in street furniture, cars, clothes. You go outside into the street and everything is hideous. Really! I don’t want to seem backwards-looking, because what we find beautiful today from 40 years ago may have seemed ugly at the time. And maybe in 40 years people will think cars and bus shelters from 2020 are fabulous.

Thomas: Who in this industry do you admire the most and why?

Lolita: We really respect Peter Saville. For his work, but also for his character; the way he talks about himself with such nonchalance.

Jean-Baptiste: In the fashion industry, I really rate Hedi Slimane. I think he is an artistic director in the full sense of the term. It’s such a clichéd term these days – everyone’s an artistic director – but he created his own world. That might seem like a totalitarian way of doing things, but I really respect him. To be a designer who changed the fashion codes of his time, which he did in the 2000s – that’s huge. He marked his era. As for artistic directors, there are loads, from Alexey Brodovitch to George Lois at Esquire, who is a yardstick for me, Paul Strand…

Thomas: Have you had any professional disappointments and what did you learn from them?

Lolita: You can’t always get it right. There are things we love and things we love less. We get over it; we don’t have that type of ego. The disappointments are of the human kind, because we work in a milieu that can be quite hard, and you have to fight. Sometimes that fighting isn’t pretty. It can make people bitter, even though, at the end of the day, we’re not saving lives. We’re so lucky to do this job; we have to keep our feet on the ground and remember that. It’s quite dangerous to take things badly and too much to heart.

Thomas: Lolita, why do you think there appear to be fewer women in this line of work?

Lolita: People think an artistic director has to direct a team, which means being strong and having a strong personality, and they don’t think a woman can do that type of role – which is completely wrong.

Jean-Baptiste: I can’t explain why there aren’t more women, except that many artistic directors have been around a long time and when they started out women were less common in the industry. But that’s changing and that’s good, particularly in photography. For ages there were only men and now there are lots of female photographers.

Thomas: Do you want to go back to working in the way that we were before confinement?

Jean-Baptiste: I have no particular desire to return to the frenzy when everything starts up again. Bad habits will get the upper hand again, and everyone will start racing towards who knows what.

Lolita: The general madness had been bothering us for a while.

Jean-Baptiste: We’ve chosen to be slaves to it and once things are back to normal, we’ll fall back in like everyone else, knowing that we don’t want it but unable to see another way to work.

Thomas: Lots of people are concerned about the density of production required now, and that there is hardly any time to create anything profound because the number of images required stifles real creation. It’s all about producing, producing, producing.

Jean-Baptiste: Images are something we consume on our mobiles, now. One image crowds out another, and everyone just flips through them. I can hardly criticize that system when I work for a weekly and produce 50 times the content of a biannual magazine. I can’t say that we should produce less, because then I’d have to close the magazine. But what are we creating? Why are we creating it? What are we trying to say? What do we want to show? Digital communication has brought an explosion of deliverables, when 20 years ago we’d produce five images and a film for a campaign. But we’re dependent on brands, and we can’t reverse that. We could be the Che Guevaras of artistic direction and insist that we’re not going to do it, but then someone else would do it instead. That’s a pessimistic vision, perhaps, but it’s realistic: a pessimistic realism.