In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘In order for our system to function,

we have to plunge completely into the

mind of the person sitting opposite us.’

A conversation with

Mathias Augustyniak and

Michael Amzalag of M/M (Paris),

22 May 2020.

Thomas Lenthal: Thank you for the portfolio. I’m very proud to have you in the next System. Could you talk us through the project?

Mathias Augustyniak: Thomas, this feels like a session with a psychoanalyst. In fact, you do kind of resemble a shrink.

Thomas: [Laughs] Let’s start the session then.

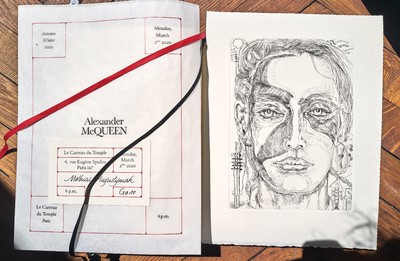

Mathias: It all started very simply when I saw the Alexander McQueen catwalk show we’d worked on. Michael couldn’t attend…

Michael Amzalag: Because I had non-diagnosed pneumonia!

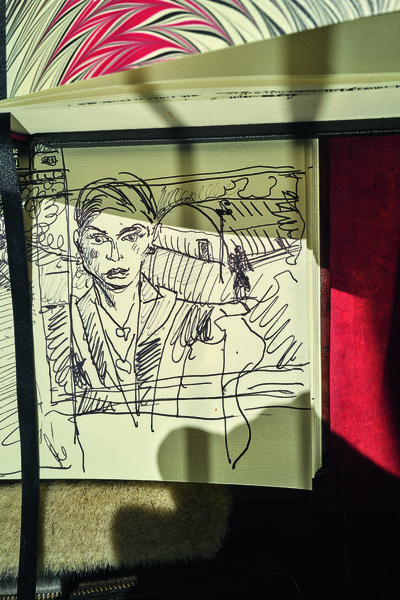

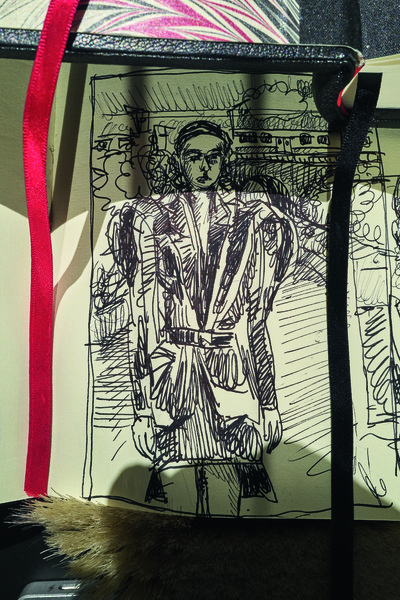

Mathias: The show was one of the last runway shows of the season. You could feel the tension rising, people weren’t that receptive to the show; they were thinking more about the rise of the pandemic. Italy had already been hit or was in the process of closing. The people came to the show, but it felt like they were more worried about getting contaminated than anything else. Two weeks later, we went into lockdown. Generally, at this period of the year, there are the shows and then the major advertising campaigns that illustrate those shows. So this time around, we thought, ‘Seeing as we’re all going to be stuck at home, we need to find another solution to understand what’s been happening.’ For us, the principle behind an advertising campaign is about both selling the products and visually understanding the designer’s work: it has to format what happens during a show. In that sense, a fashion show is not a performance, but rather a space where information is presented. Before anything else, a show is where fashion people come to understand the objects that are presented to them, which they then transcribe in words if they’re journalists or through images if they’re artistic directors. The portfolio we put together is a visual essay, made with limited means, because we couldn’t travel, that illustrates the most recent Alexander McQueen collection. We were lucky for this project because when we work with Alexander McQueen, we get to take part in the research trips that [the house’s designer] Sarah Burton takes every season before beginning to work on a collection, during

which she dives into a different part of the UK. For the last season we visited Wales. These trips aren’t about her trying to be ‘local’; she’s not looking to do an interpretation of anything regional she sees. Rather it becomes the starting point for her inspiration and from which she then extracts specific references. So, we took the images from that research trip – views of Wales – and mixed them up with illustrations of the clothes. It’s not necessary to say exactly where things happen; it’s an allegory that allowed us to create visual and emotional density. There are some images that explain where things are happening: so it’s in Paris, which is why there’s a work table; it happens in front of a window, because we were in lockdown for two months. And there are two views of an empty Paris because I thought it was interesting to put Sarah Burton’s work into perspective, with the idea of her being inspired by Wales, working in London, and then the clothes going off all around the world. That’s how it happened. An interesting point is the first image we see in this visual essay. It’s an illustration, an engraving from a limited series, that shows an image from the previous campaign; it invites us into the new campaign. On the left-hand page, there’s a layout that shows all the typography and graphic work that has been brought into the brand, including a reworking of the logo, to signify the fact that it’s now Sarah Burton operating within this brand called Alexander McQueen, the name of someone who died. That was the starting point. Also contained within that idea is the start of a discussion about what constitutes an advertising campaign. What is a fashion image? What is the work of an artistic director?

Thomas: One of the things that characterizes your career is your ability to weave long-term relationships with your clients. It’s like a really long conversation, one that’s very articulated, complex and deep. It’s very sophisticated and unusual in the history of fashion advertising.

Mathias: That’s a way of summarizing what we do or at least the way we approach a project. To that I would add that we also really like having several long-term relationships at once. They all happen at the same time, but we put a lot of effort and deep-dive work into each one. They all exist alongside each other without contradicting or cannibalizing each other, without repeating each other or themselves. But in order for our system to function, we really have to plunge completely into thmind of the person sitting opposite us; we have to do a full survey. Sometimes to understand a story, it takes time, we have to go deep so we can resurface with what we need. That’s how we work with our clients, whether it’s Balenciaga, Calvin Klein, Jil Sander, or a theatre in Brittany.

‘It takes a lot of work and a lot of time for an idea to ‘ripen’. Every existing philosophy is nourished by other philosophies, all digging for the same thing.’

Michael: Repetition shouldn’t be criticized, though; we have the right to repeat ourselves! As long as there’s nothing formulaic about it. Undoubtedly certain solutions occur that we feel we’re allowed to use again.

Thomas: Do you have an example?

Michael: The drawn image in the portfolio was and is inspired by the previous season’s campaign. That’s a mechanism we already used at Balenciaga: a drawing from the past can become an image for the future. For Givenchy menswear, too, and for the Loewe relaunch, when we worked with pre-existing Steven Meisel images that had been published in Italian Vogue; that famous story inspired by Alex Katz, which was itself already an interpretation. We have this idea of having an interpretation of an interpretation of an interpretation, which becomes the starting point, the mood board. Here, instead of trying to reproduce the interpretation of the interpretation, we decided we’d prefer to show the source, deliberately.

Mathias: It also had an economy of means. Considering the context, the fact we re-purposed and reused was almost an ecology of images and signs. It takes a lot of work and a lot of time for an idea to ‘ripen’. Every existing philosophy is nourished by other philosophies, all digging for the same thing. It was about continuing something that existed before, but that can be reapplied, almost like deciphering another present.

Michael: We can create small and experimental solutions and then use them on a more industrial scale. Another example would be the alphabet, which we used and later reincarnated for a Calvin Klein campaign and later requoted in a more obvious way when we worked with Madonna on American Life.

Mathias: It’s like a tool that works, that’s why it’s important to us, it can always be used for something else. Like a grammar. One of the visual essay’s images has an iPhone showing a live Instagram stream of an interview with Jean-Luc Godard next to an image based on a Polaroid from a previous campaign, a lighting test… All these images are associated, it’s like a sentence.

Thomas: I get the impression that you build restrictions into your work. When you’re commissioned by a client, you talk to them and then you yourselves construct the boundaries within which you then work.

Mathias: When someone asks a question, either it makes sense and we can answer it straight away or, if we think the question is badly formulated, the first stage is to reformulate the question in collaboration with the person. Not ignoring what they want but attempting to see it from the outside.

Michael: It’s first and foremost about defining the context in which the signs we will make will appear and knowing how they will circulate. We use intuition and analysis of the context to see which platforms or channels we can use to tell the story.

Mathias: There is a period of listening and research, almost like at the psychoanalysts. You have to listen to the client and hear what they have to say. The hardest thing when we work for a big company is not being able to identify the person who is speaking to us and who we’re speaking to. People often ask why we don’t do things for the big groups and it’s often simply that we like to be able to talk directly to the person we would work with. When we worked with the Galeries Lafayette Champs-Élysées, for example, it worked well because we were talking to the person who was investing in that project – he was taking as much risk as we were creatively. One of the first times we experienced a genuine and direct relationship when working with a big multinational house and brand, was with Calvin Klein. Mr Calvin Klein himself called us up – not a head of a department, not a chief officer of something or other – to express something strong about his brand at that moment. We told him spontaneously what we thought was missing from his brand, and that is why what we did worked. He had understood that his brand’s message wasn’t working, and the work we did gave new strength to his business because it embodied his voice at that moment. Like, ‘I am Calvin Klein and I am still the master of this business – whether you like it or not.’

‘People often ask why we don’t do things for the big groups and it’s often simply that we like to be able to talk directly to the person we would work with.’

Thomas: Going back to fashion photography, what makes an image successful?

Mathias: A fashion image is in no way scientific, but at the same time it is very constructed and grammatical. We begin by saying that the person who is photographed and wears the clothes has to be credible as a character. It’s a portrait, whether the person is real or imaginary. A fashion photograph is the synthesis of several people’s visions. It’s like the eyes of a fly: 10 pairs of eyes making one image.

Michael: It’s the crystallization of a collective desire in a single place.

Thomas: That’s a really lovely way of putting it.

Mathias: There are lots of fashion photographers, but only a few who can co-pilot a very complex machine. Being able to achieve that level of crystallization is something you can’t invent.

Thomas: Photographers have very different ways of reaching that. Steven Meisel, for example, works incredibly quickly.

Mathias: We’ve worked a lot with Steven, particularly with the project for Loewe, and yes, he works very quickly, like a virtuoso, but he also takes a lot of time to imagine and really invest in each image. He is a brilliant man who always needs to be challenged, and things need to be prepared in advance, so he can perform his solo well. When he arrives, he just pulls everyone along with him. We did studio work with him and we had a seaside set. He arrived, put on some music, got the wind machine going and even sprayed some water, and, for those five minutes, you really believed that you were by the sea with this model. When you talk before the shoot, he’ll say, I can give you this and this, because he has a register of all the images he’s taken in his mind – and he knows how to create a new image in the space between two old images. That’s how we’ve experienced working with Steven. He understands that the interest of a fashion photo is to make the viewer travel, take the person looking at the image on a journey. David Sims’ photos for Helmut Lang did that, too. He photographed his friend and didn’t show the clothes – but the image took us on a journey.

Thomas: Do you have any memories of fashion photography from your childhood or adolescence?

Michael: I remember attending a Jean-Paul Goude event at the Fnac Forum [a store in central Paris] where you got a free Citroën poster signed by Grace Jones who was pictured coming out of a mountain. That was 1986, so I was 18. At the time, though, I’m not sure I identified it as a fashion image. It just crystallized something I couldn’t name.

Mathias: I discovered fashion images later, when I got to Paris. One of the first things for me was the images that Peter Saville, Marc Ascoli and Nick Knight did for Yohji Yamamoto.

Michael: The Yohji-Marc-Peter triangle made things very clear in my mind.

Mathias: We then talked to Peter and told him that he opened the way for us. And it’s why we insisted on meeting Marc, and when he saw our work, he fell for it straight away. Fashion imagery was an entry point; we identified this space as a place to make images.

Thomas: Before that, fashion images hadn’t really registered?

Michael: It was later that we understood it. It was when we worked with Marc that we understood fashion through fashion imagery. Before that it had been about images more generally.

Thomas: Like what?

Michael: Mathias and I were spoon-fed artistic experimentation by our parents. I remember going to see Le Golem by Niki de Saint Phalle in Jerusalem; that was certainly a visual experience.

Thomas: Mathias, wasn’t your father an art teacher?

Mathias: Yes, both my parents were. At my house we always had Charlie Mensuel and graphic-design magazines. There wasn’t Pif Gadget, because they weren’t communists. There were photo-reportage magazines, because they developed their own photos.

Michael: We had a dark room in the house, too. It was the era when everyone had an enlarger at home.

Mathias: When we went to Italy, for example, I would have to visit the entire Uffizi if I wanted to get an ice cream. We’d go to Dijon not to buy ginger bread, but to visit the art museum; we’d go to Beaune not to buy wine, but to see The Last Judgement.

Michael: Then the Pompidou Centre opened and became the place to go as a teenager. We all had the number of the call box under the escalators there and we’d call each other on it.

Mathias: Our visual resources were more art based. At the Pompidou, I remember seeing Cy Twombly [in 1988], Ed Ruscha [in 1989], and the exhibition Les Immatériaux [in 1985]…

‘A fashion photograph is the synthesis of several people’s visions. It’s rather like the eyes of a fly: 10 pairs of eyes making one single image.’

Michael: I must have seen Les Immatériaux about 100 times.

Mathias: We arrived in the fashion world through all these other things; we were cultivated but not that cultivated. Then by going into the fashion world, with Marc and Peter, we realized it takes time to fully understand these people who are walking encyclopedias. People are very quick to judge the fashion world when they don’t know it.

Thomas: Another artistic director was saying there is never enough time to really go deep, but I don’t get the impression that’s the case with you.

Michael: No, because in theory, our methodology doesn’t adhere to the dictatorship of the to-do list or box ticking.

Mathias: It’s true that we live in the time of the to-do list. Before you even start a project, you sometimes need to say, ‘Maybe we don’t need to do too much, maybe one image would be just as efficient.’ But there’s a sort of one-upmanship, so people think, ‘If I put it everywhere, I’ll be seen.’ But we all know that isn’t true. A brand can exist without having put any ads on TV or can exist having only ever done ads on TV; a brand can exist with just one store in Brooklyn. You can exist; the problem is the fear of not existing, this terrible fear of not being seen. So even before knowing what really needs to be done, you can end up with this huge, terrifying to-do list. It’s like someone gives you a list when you turn 18 with everything you have to do before you die on it. What we try to do instead is find the focal point so we can first work out where we’re going.

Thomas: Do you think that this moment, this sort of suspension, will impact the future?

Michael: Once we manage to address the panic in which everyone is drowning right now, at some point we have to redefine how we move forward.

Mathias: It’s ultra-important that we can talk among ourselves in a nice way; that’s going to be vital. We need to talk to each other, to forget all the legalities and just talk properly, fashion-industry people to fashion-industry people, so we can bring back this desire to the largest number of people.

Thomas: We had reached a point of hysteria before Covid-19…

Michael: I don’t want to talk in those terms, because it’s easy to say it was too much, and forget that the system in which we work and function has produced things of value. That said, we do need to address how we represent desire when this is over.

Thomas: So it’s like a year zero?

Michael: No, because nothing has disappeared; everything is still here.

Mathias: The danger lies in saying that before we were the bad guys and then we’ve gone through purgatory. There shouldn’t be an overly Christian discourse about all this, like before we were sinners. The problems remain unresolved, but we shouldn’t deprive ourselves of extravagance. Sometimes things are more pragmatic, others they are more extravagant, both need to co-exist. That will be complicated in my opinion. Of course, we can do things in a restrained fashion, but certain things need more breadth and sweep.

Thomas: We shouldn’t lose our faculty to be whimsical and idiosyncratic.

Mathias: Exactly. Because that is what, to return to the fashion world, fashion is good at. We do totally random things and those really random things release human emotions.

Thomas: You said a runway show isn’t a ‘show’, but I feel like it is…

Mathias: Our fantasy runway show isn’t a big ‘show’. I’m not saying they aren’t, just that to us they’re not like ‘shows’ or stage plays, they’re events unique to the fashion world that allow people to share information and learn.

Michael: They’re like fashion brands publishing an annual report every six months.

Mathias: The problem with more and more fashion shows is that there are too many spectators. Recently it has been so much about the spectacle, the ‘show’, which leaves me cold. It was like being really bored at the theatre and you keep falling asleep. None of it made sense anymore. Certain shows we saw before lockdown had good ideas, but you didn’t know where you were anymore. Think back to Alexander McQueen’s shows and they were spectacular, but they weren’t simply showy spectacles. Yes, they used allegorical fantasy, but they were never Harry Potter on Broadway. They had great eloquence, they had a message – and they exuded a sense of fashion.

Thomas: That’s a good place to end. Thanks so much to both of you.

Mathias: You’re welcome. Same time next week for the next shrink session.