In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘It’s like being a conductor

who controls the orchestra with

skill and subtlety.’

A conversation with Marc Ascoli,

30 April 2020.

Marc Ascoli: I’m in Paris and it’s not been unpleasant, until today. What drives you a bit mad is how the symptoms keep evolving, so I’ve decided not to take everything I hear too seriously. If it weren’t for all the news on TV, this could be like a holiday.

Thomas Lenthal: Yes, an unexpected holiday. If your life is comfortable, it’s almost nice, but if your life is difficult then it’s 10 times worse. This ‘reset’ is not going to be good for small designers with more complex ideas, for example. There is going to be a brutal cleansing of the market, of brands. Lots of labels are going to disappear.

Marc: Like those small businesses that had problems getting established?

Thomas: Yes, but even medium-sized businesses. And it disturbs me, because we’ll probably end up with a much poorer landscape. So many brands have emerged in the past 10 years or so – just look at all the online shops – maybe the whole ecosystem has become too disparate. You go on to some of these websites and see 500, 600 brands. That’s insane. I think there will be a reset, but this isn’t my area of expertise; maybe I’m wrong.

Marc: Perhaps it’s a good thing. Things will be opened up, tidied up.

Thomas: I don’t know. I don’t think I have any profound insights into the situation. Let’s talk about your portfolio, because you made it spontaneously and naturally.

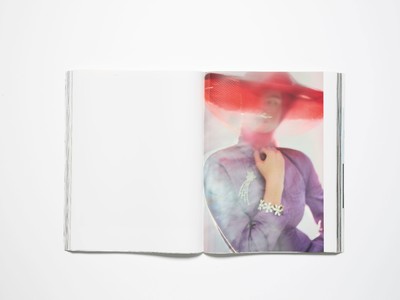

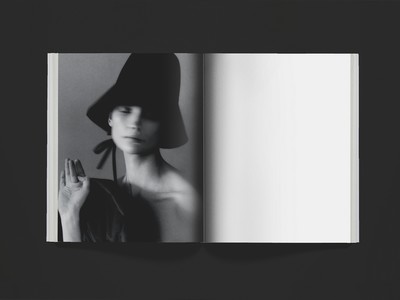

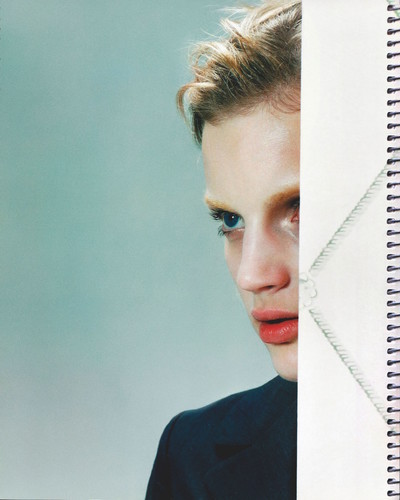

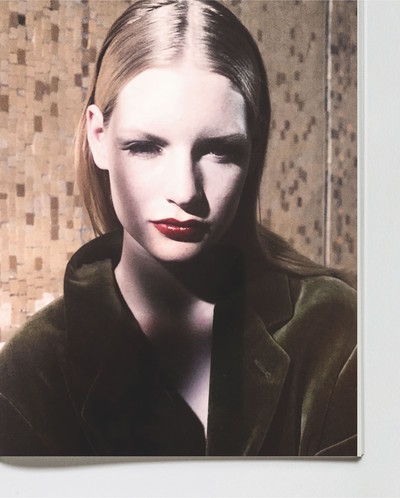

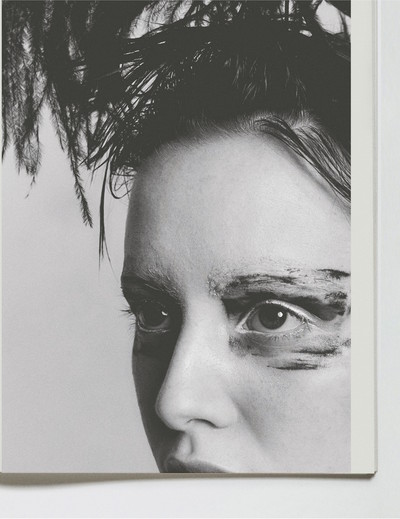

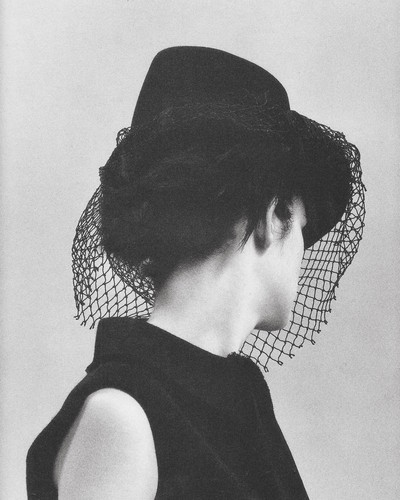

Marc: To be honest, I didn’t spend a lot of time considering it. I didn’t go round and round in my head wondering how I would do it. I thought it about it in a personal and a practical way, sensitively and emotionally. It contains elements that convey what I want to feel today – not yesterday or tomorrow – when I look at a portfolio of images. I also wanted to put my past work up against my current work, because I’ve got a lot of ongoing image projects. I wanted to find a balance between the two. It all happened quite naturally. I got the idea when I was talking to you, even if it wasn’t 100% formed. I wanted to say something very natural and delicate. When we finished the pages that you offered us – I say ‘we’, because I was working with a studio – we wanted to make a ‘total impression’; you turn the page, turn the page, and… toc! So I took care making this selection. At first we put 1990 David [Sims] next to David from today, but then I found that really pretentious. So I threw things up in the air a bit and played around, totally spontaneously, mixing an image from Jean-François Lepage with a black-and-white image by Max Vadukul, and I realized that was pretty strong, and then it all began to flow. What’s the ‘connection’ between the images? It’s in what I’ve just said and the fact that I directed it. No, not directed; I provoked it. I got things going. I say ‘I’, but these were images produced after discussions with Paolo Roversi or Sam Rock. I talked to Johnny Dufort, who did such a strong look with the make-up, and today’s superstar, Lotta Volkova, our friend, who is really extremely talented, and who you work with a lot. She spent some time here, and I only made one image of her work. So these were the things that were blended together, in a way; it was curious, a synergy.

Thomas: When I saw your portfolio, I thought it was fantastic; a collection of portraits when you could have chosen to do only looks, or looks and portraits. Something I think you have contributed to the history of our profession is how you take these models who are photographed and made-up in a certain way, with their hair done a certain way, so that the fashion has to be encapsulated in a face. I like that, because there is nothing more captivating than a face; for me, it’s the most dazzling spectacle. I have always found it such a beautiful and touching approach: crystallizing fashion around the face, the head. One of the things I really love about your work, is that it feels like a dreamy, fantastical portrait gallery. Always clearly of a person, always someone sublime. So it’s interesting that you didn’t mention portraits when you talked about your portfolio.

Marc: I see them more as moments. No, you’re right, they are also portraits. I’m looking at them now. I hadn’t thought about that! You can’t see the fashion.

Thomas: That’s what’s superb, that they don’t show the fashion. I remember an art director at Dutch who put fashion credits on pictures of nudes, and that worked really well.

Marc: Matthias Vriens.

Thomas: Do you remember that naked issue of Dutch [in 1998]? Eighty-five pages, black-and-white, of nudes by Mikael Jansson. Maybe there was colour, too; it doesn’t matter. Each image was credited to a brand, and it worked incredibly well. You just had the name of the brand; not a scrap of clothing in sight.

‘I’d go out in the 1970s and see Grace Jones and Jerry Hall dancing in clubs. These women had long, beautiful legs, and everything smelled of patchouli.’

Marc: I was also thinking about how to regenerate these images. They first existed in a certain context, and when you take them out of that environment – a magazine, a catalogue – and use them in another, then you reorganize, reinvigorate and regenerate them. That opens them up to other ways of expressing the emotion you are trying convey.

Thomas: Another thing that strikes me is that if you look at your portfolio, unless you’re a great connoisseur of models, it’s impossible to put a date to some of the images, even though some of them are 30 years old, some are 10 years old, some are six months old. That’s how you see an artist: nothing is passé or old-fashioned; nothing is kitsch. You don’t find them only ironically interesting. They have the freshness of a good work of art.

Marc: That’s a lovely compliment, and you’re asking a very precise question. It’s not like I produced it just like that; the process was harder than that. I definitely didn’t want to do retro or nostalgia. There were images that I made for the first issue I did at AnOther. They featured these fabulous, extraordinary and beautiful feathers. But they immediately made it look passé. They looked like that image that we all love of Marlene Dietrich. In this context, the old film thing didn’t work. There’sthat really strong make-up look by Thomas de Kluyver; he just went for it and destroyed the prevailing aesthetic of older make-up artists with an extraordinary freedom, an energy. He has an extremely modern touch, an amazing energy.

Thomas: Do you think restriction is useful or even necessary when it comes to creative work?

Marc: I find it helpful when people explain what they need extremely clearly to me.

Thomas: [Laughs] Have you ever met a client who could do that?

Marc: You know, part of my work is to know how to talk to people. Sometimes I need to put someone at their ease, over several meetings. There are clients who want old and young at the same time, cool, but not too cool, chic, but not too chic. I just finished a project with a client I nearly killed halfway through, and I’m almost glad that there’s the lockdown so I don’t have to carry on. There are always people who are in roles they shouldn’t be in, and who have responsibilities that are beyond them. Let the people who know what they’re doing do what they do. You shouldn’t have a CEO giving directions, just because they have an armada of marketing behind them. But I like restrictions because I regard them as a light that I can follow, and I always start in darkness. How many images do you see every day? How many elegant, chic, modern profiles? I’ve been doing this for a long time, and I’ve worked on the topic several times, though this is the first time I’ve done it in a magazine [AnOther], and with an English staff.

Thomas: From what you’ve told me, your English has been sketchy for a long time, which is astonishing considering most of your career has involved working with English speakers. It’s interesting to think about verbal communication rendered a little awkward by an imperfect ability in English. In New York in the 1980s, there were so many French people in our industry who managed to have great careers with 50 words of vocabulary. I’ve known people who have made a fortune in business with an elementary-school level of English.

Marc: It’s a strange experience, but I love it. In the 1980s, in the beginning, I would explain what I liked; I used to get all the books out, look up all the references, look at the photography. But now, and I think this is why you like my portfolio, I’m more interested in creating an emotion, like you all did on the cover with Yohji [for the last issue of System]. What’s really important with a cover or a feature is that you should feel an emotion being expressed that draws you into the idea of buying the magazine.

Thomas: That’s interesting. Of course, there are other constraints that can be severe and are nothing to do with the difficulty of a client. You can be restricted by time or by money. Now, for example, we can’t travel, we can’t have more than three people in one room.

Marc: It definitely fuels the imagination. And it also triggers another creative engine: anxiety. When you’re anxious and nervous, you can find certain value in that negativity and pessimism to wind yourself up, to decide to do something new. Maybe you can’t afford to do it one way, so why not do it another? When I started out as an art director, I had huge restrictions. I always wanted to show that you didn’t have to do the same thing for everyone. I didn’t want to do what Peter Lindbergh had done at Comme des Garçons, just to give you one example. His catalogues were amazing and extremely successful. They were astonishing: the casting, the styling, the clothes; everything was impeccable. Show those catalogues to anyone today, to designers you know, and they’re all, like, ‘I want to dress like that now.’ Azzedine was really influenced by them. Martine [Sitbon] was influenced, too. Even Jonathan Anderson. I saw his last show for Loewe and there was lots of Comme in there, lots of Japanese. But Lindbergh presented it perfectly. And Arthur Elgort; he did some beautiful images. Then I arrived with a new team of photographers, and my restriction was to break out by doing something new. Those restrictions – to be new, more experimental, bolder – really put me in it. As for the restrictions you gave me, I had to think about what I would like people to say when they encounter a small portfolio like this, and how it would change when it was surrounded in the magazine by other artistic directors’ different views and voices.

‘Yohji is such an intellectual; he thought it was odd that I could be so passionate about fashion photography, about something he thought was futile.’

Thomas: You’ve already answered this to some extent, but for you, what makes a good fashion photograph, and has that changed over the course of your career?

Marc: A beautiful fashion photograph should seduce; it’s always about seduction. That’s why we do it: to express a certain form of seduction, to draw people in, to look, to be fascinated. It should be something that we think we know but don’t; that we’ve perhaps seen before in a different context, but when we see it in fashion, it seems true. It should remind the viewer of something in the collective memory. You look and you think, ‘I’ve seen that before’, and then realize that you haven’t. Some people are very talented at fashion photography, and some people ruin it; some ennoble it, some torment it, some are really classical. But I like all of it, I don’t prefer Juergen [Teller] over Nick [Knight]. Did I have that idea when I started out? No, it grew as I went along. I learned everything on the job. I’ve always worked for myself; I was never someone’s assistant. This is a profession you get better and better at doing, because it’s a career involving direction. It’s like being a conductor who comes to control the orchestra with more and more skill and subtlety. Of course, you can always encounter idiots who want to say the opposite of you, and that’s annoying: graphic designers, photographers, models. That’s why you need subtlety to get through all of the obstacles. You learn to accept them more easily than you might have done a few years earlier. Before, I could be absolutely horrified by certain attitudes, but now I can see that it’s part of their creative

practice. I have become more understanding. I don’t say, ‘I’m never going to work with you again’ if I encounter an idiot. I’m more patient, now.

Thomas: Was there a defining image, reference, person or moment from your teenage years that looking back proved instrumental in projecting you towards

a career in fashion and art direction?

Marc: A detonator? That’s difficult. I’d go back to the 1970s. I used to go out and see models dancing in nightclubs with the VIPs. They were all brilliant and charming; these women had long, beautiful legs: Grace Jones and Jerry Hall; and everything smelled of patchouli. Karl [Lagerfeld] would be in a corner, Kenzo would turn up with his polka-dot bow tie.

Thomas: Did you go to Le Sept?

Marc: Le Sept, Le Palace, but mostly to Le Sept because I was so young. It really left its mark on me. I was disgusted, at times, too, because there were dark

things going on; it was weird. There was a lot of sexuality in that period – it was pre-AIDS – and some of it was quite violent. I remember it well – it’s really vivid – and I remember the aesthetically striking images, like Antonio Lopez’s, for example. If I see them today, I’m immediately transported back to that time. It really made an impact on me: the luxury; the way they moved; the ‘proudness’, even arrogance. But it was also very open; not regimented and managed like parties today. It was much less ‘business’.

Thomas: There was a fraction of the money around then compared to today!

Marc: It was more accessible. It was a demonstration of how to be bohemian, chic and flamboyant; I can still see the satin, the dots, the sequins. And it made an impact on me, in that I thought it would be amazing to be part of that world. When I did the Chloé book a few years ago, I threw myself into the archives and found myself back in that period. It was so extraordinary: the energy, the models, the photographers. It was such a memorable time, and then it changed for me, because I started working with the Japanese. That was the total opposite in terms of fashion. Yohji is an intellectual…

‘A beautiful fashion photograph should always seduce. That’s why we do it: to express seduction, to draw people in, to look, to be fascinated.’

Thomas: It was interesting how the pair of you combined two worlds that, on paper, appeared to be polar opposites.

Marc: What I brought to Yohji were energy and ‘fashion’. My tastes are, if I’m being honest, light-hearted and fun, sort of deep with a form of lightness. He liked that a lot; he enjoyed the story I was telling, that joyful vision. His fashion was serious, magnificent and ostentatious, and I think he liked the idea of putting it on girls who were kind of cool. He gave me free rein with the make-up, hair and photographer. It was necessarily glam, but it had a certain energy.

Thomas: With Yohji, I remember there was the cigarette and the woman on the leather sofas.

Marc: Yes, and Yohji both liked it and didn’t like it. He wasn’t, ‘wow’; he had to be pushed a bit. You’ve interviewed him, you know what he likes; he loves black and white, for example. At the same time, he let me work. He liked that I was enthusiastic. He loved that I was all, like, ‘Wow, look how beautiful she is! Look at this!’ He was such an intellectual; he thought it was so odd that someone would be so passionate about fashion photographs, about something he thought was kind of futile and beneath him. But then again, it worked; he found it entertaining and it gave him a lot of energy for his work.

Thomas: Can you give an example of what you find most intuitive in your work and what you tend to overthink? I was struck by how you said that you didn’t think too deeply about your portfolio, but when it was done you realized it had a depth that you hadn’t necessarily planned.

Marc: It’s all about awareness and confidence. For me, things function because I make sure to communicate directly with the person I’m working with. I communicated with Yohji, with Jil [Sander], and now I’m doing the same with Julien Dossena [at Paco Rabanne]. Of course, when you start out, you’re anxious, not least because there’s a lot of money involved. Everyone knows what it’s like to be asked to do something and you don’t know whether you can deliver. And I have a long career, a weight of experience, high standards. So when someone hires me, behind me there are all the images I’ve done, the people I’ve discovered. People might expect something specific, but you can’t produce exactly what you produced years ago, the way they want it. The situation is completely different. It’s always helpful to remember that each time is a new, amazing chance to produce beautiful images. That is the stimulus. Thomas, when you look at the Dior campaign you did with Nick Knight, you must feel such pleasure.

Thomas: Yes, that was an absolutely sensational time. It was fabulous. It was an extraordinary collaboration with Nick. Before we began, I took Nick some drawings by Antonio – it was the two girls on the motorbike – and we shot Gisele and Rhea, one behind the other, in the sky. It was pretty amazing. And we had a week to do the images.

Marc: And John [Galliano] was so excited and happy with it.

Thomas: He trusted us; he was happy. He would come and go. He could see that it was working brilliantly. It was exciting. Another question: do you prefer your work to appeal to a niche, specialist demographic or do you prefer a broader audience?

Marc: Both require the same level of work and commitment. To do something really cool for a magazine, I have to find new talent or set things up or find something that’s ‘elevated’. The English are always saying that word and I love it; it’s so chic. Then when I did the Armani beauty campaign [in 2018], it was for a

billion people. When you start on something as important as that, you have to get over some of your own issues. It really made me stronger, because I was convinced I couldn’t do it. To be honest, I prefer working with people who understand it all. With a connoisseur, I can play with subtleties. I can make a tiny adjustment, and for them it’s something completely new. But really, it’s always about the individuals, the people you’re working with. When you talked about the commercial and financial crisis that is going to hit us, I immediately thought, ‘We need good quality people now.’

Thomas: You’ve said that when you worked for Yohji, you talked to him as if in an imaginary conversation. It’s awful working for people you have no desire

to have a conversation with.

Marc: But do you manage it?

Thomas: Sometimes I find myself in work situations where conversation seems impossible, because there is such a gulf between you and the other person. It’s not necessarily a cultural difference, but when there is insincerity in the relationship. That’s awful.

‘When you’re anxious and nervous, you can find certain value in that negativity and pessimism to wind yourself up, to decide to do something new.’

Marc: When I see certain ad campaigns, they have a coldness about them, something mechanical.

Thomas: It feels like they’ve just gone through the motions. It’s completely meaningless.

Marc: We have to get out of this mechanical vision of the subject. It feels like we are drowning in so many products with only a narrow creative idea behind them. These designers are all on a conveyor belt, because they’re dealing with people behind the scenes who don’t communicate. They don’t discuss anything with the designer. If stopping for two months restarts the conversation…

Thomas: Describe a professional disappointment and what you learned from it.

Marc: I’ve been working for a long time, so there have been a few. And there have been as many delightful times as there have been disappointing ones. Disappointment always arrives when you are least expecting it, and you never expect it to happen to you! Of course, there’s the cliché that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, and it’s true. I’ve had times when life has punched me in the face, or no one has been willing to help me out. Remember when you did that article about me? I really appreciated that, because at that time…

Thomas: Let’s just say that you didn’t have a private jet to lend me! [Laughs]

Marc: Everything that has happened has taught me not to have delusions about things, to take a step back, to be less fiery. Coming from Tunisia, I’m quite dramatic, quite southern, but life has calmed me down.

Thomas: Which person working within the fashion industry do you most admire, and why?

Marc: In the fashion world? I don’t have a single icon; I’ve got a few in my pantheon: Avedon, for total classicism. When I see certain images he did, I’m still impressed. That series of little adverts he did in Japan in the 1970s, you can see them on YouTube. I could have worked with him, but never mind. I’ve always liked Steven Meisel. I was clearing up earlier and I saw the 2012 Prada campaign he did, which was extraordinary. There was nothing mechanical about that; you really got a sense of the Italian woman. It’s hard, because you meet people in your everyday life who charm you, but in general, it’s people who you admire from afar who inspire you. I don’t really know Steven very well, even if I worked with him at W with Edward Enninful. What he delivered was great; Edward was really into it. There are other photographers I admire, but I won’t mention them all. Irving Penn, for example. What I don’t like is when people reveal everything about themselves. When I’m a real fan of someone and admire them, I’d rather not know everything about them. I need to preserve some glamour and mystique.

Thomas: You have to maintain a certain eroticism, some mystery. If you know too much, the seduction wears off. Another question: what do you know now about the fashion industry that you didn’t when you were entering the industry? It’s changed so much…

Marc: True, but I’m not pessimistic. This industry is made up of people who respect each other. I mean, look at how you have invited everyone for this issue, you didn’t have to do that.

Thomas: I’m giving exposure to competitors!

Marc: But you’ve done that a few times, haven’t you?

Thomas: Yes, it doesn’t bother me. I’m a good comrade! As things hopefully return to some level of normality, will your impulse be to explore notions of fantasy and escapism, or will you be more inclined to double-down on realism, documenting the moment? Your world is very dream-like and lyrical, in a subtle and elegant way.

Marc: Definitely less fashion. By that I mean fashion in the sense of ‘high fashion’. Fashion in the sense of Grand Hotel. It will be more considered, more sensitive. Not just documenting people who are only obsessed with one thing. People who also read, maybe, or who are concerned about the planet; people who are interested in more than shopping or choosing their next lipstick. I definitely want to document something more meaningful; something that opens us up. I think that is the first essential thing.

Thomas: No more frivolity.

Marc: No, no, it would be awful if there were no frivolity!

Thomas: Of course, frivolity is part of civilization.

‘When I did the Armani beauty campaign, it was for a billion people. When you do something as big as that, you have to get over some of your own issues.’

Marc: And it plays a huge part in the ingredients of our subject. It’s strange, I’ve done AnOther for two years now – four issues – and some things are already old-fashioned. You can’t keep telling the same stories, or telling stories in the same way. This crash, in these two months, is incredible. It’s a real rupture. I don’t know how people are going to put on fashion shows. I don’t think there’ll be many, in any case. They won’t be able to afford to put them on or they won’t have the clothes.

Thomas: Or the distancing issues will prevent them from happening, maybe. Perhaps they will be banned.

Marc: If we were to carry on in the way we were before, it would be a bit indecent.

Thomas: With the big shows, I think that if you’re not there in-person and you only see them on TV, they have absolutely no value as a spectacle. The way they are filmed is very…

Marc: Cheap. You remember the show we both saw at Chanel with those huge chandeliers? It was so real, but when I saw the photos it looked totally bourgeois. The lightness of it all was gone.

Thomas: People will have to find a way to make them interesting even if you are watching them in your own home. It’s a question I ask people, because I see them spending ridiculous amounts of money on a show that lasts 15 minutes, put on for people who are barely interested. The public version should do justice to the money spent. It’s a real question: how do we represent things now?

Marc: It’s important. It’s what I’ve been discussing with Jefferson [Hack] and Susannah [Frankel at AnOther]: how to produce images, how to do photography.

Thomas: You’re not a monthly, you’re a bi-annual. Can you imagine what it must be like at a monthly? You have no staff; you have nothing. Your means of production are on standby; you can’t send out your teams; you have to do everything at a distance. It’s bizarre.

Marc: And you can’t show what you used to show in the same way. You just can’t. It won’t work in the same way. Everyone will have to ask themselves the same question, and I don’t know the answer. I want to reveal something different, but I’m also here to make people dream. That’s my job. If you want to talk about ‘magic’, then that is my magic.

Thomas: There’s a very nice term in English that doesn’t really exist in French: escapism.

Marc: It’s great. That is my job: escapism.