In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘Our background is definitely not in

fashion; we’re from a more art-based

and critical-culture background.’

A conversation with Oliver Knight

and Rory McGrath of OK-RM,

5 May 2020.

Thomas Lenthal: Could you walk me through your portfolio?

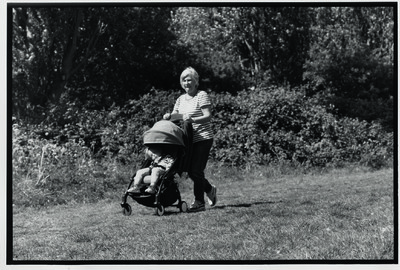

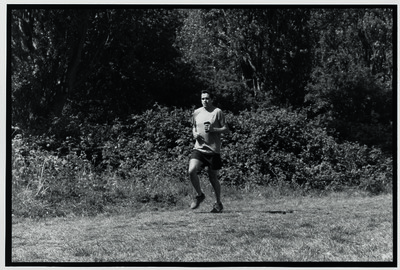

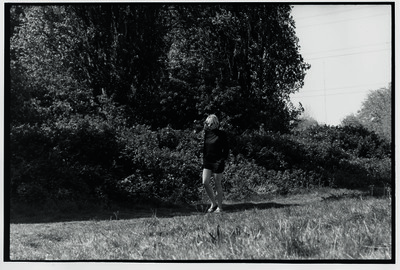

Rory McGrath: We haven’t really explained it to anybody, so this should be interesting! Obviously we’re in a complicated time, and one of the things that intrigued us about your invitation was that you were interested in our reaction to that. When we work with fashion, we really think about storytelling and articulating the philosophies and the ideas that are emerging around whatever we are working with. In this case, it was all about the current situation; it’s all about the ideas and reflections that are emerging around us. On one hand they’re very local, so it’s very much about what we see in our own little communities. But we’re also obviously in touch with friends from all over the world, and we’re sharing big ideas. Big reflections. There’s this kind of beautiful tension between this very local, very small world and big-world thinking and reflections. So that’s what it’s about. It’s about Esther Theaker, a photographer we often work with and who is based here in London, five minutes away. We work with her on our projects for ALYX, as well as on our self-initiated and personal projects, too. We are friends and we work together effortlessly. She has a really beautiful honesty in her photography; she is really against anything contrived. It’s not point-and-shoot, because she really takes a long time to observe situations, often quite peacefully, finding moments in everyday situations. That’s what this is about: it’s her in Hackney Marshes, which is a park here. We felt that the park was very important, because that’s what everybody has been doing, rediscovering the nature around us. And London is full of it. This area, Hackney Marshes, is like being in the middle of nowhere. People are there exercising or walking with friends. We were up there just before the shoot took place, and it’s so beautiful. Now, for the first time in a long time, strangers are acknowledging each other up there. In places like London, there’s often a tension with that.

Oliver Knight: One of the things that we’re interested in was about how it’s such a personal time. How people are getting really down to basics, doing really normal things. Everything feels more private; even if you’re in public, there’s a privacy to it. That contrasted with the subtitle, which started off with us taking extracts from the news. Things that we read that we really enjoyed. James Taylor-Foster then wrote and added to it.

Rory: James is a curator in Stockholm, and we are working together on a few projects at the moment, all around empathy. James is really good at being a companion and spotting moods, like the moods that surround us. We talked a lot about empathy with our collaboration. So this is a text that also deals with that. It deals with the sense of how do you propose empathy? How do you create a sense of empathy?

Oliver: With how it relates to fashion. We essentially see fashion as a vehicle or a platform for communicating ideas, but this is a key moment for communicating something that’s more related to life than it is directly to fashion. It is an opportunity to talk about ideas.

Rory: And we were really excited by the context that System has; it’s so powerful. So placing a work like this inside System is really exciting for sure.

Thomas: Is the film-still aesthetic something you’ve explored before? It does resemble a number of film stills collected together, which creates a strange narrative. It’s really compelling and interesting. It even reminded me, perhaps because I’m not English, of Blow-Up to a certain extent. Your portfolio felt very English and still fashion-related. I think I’m over-reading it, but it just felt related to something from the 1960s.

Oliver: We work as art directors and graphic designers, and we work on bigger branding projects for fashion brands. We work in many contexts. It’s not something we have a huge background in. Our background is definitely not in fashion; we come from a more art-based background and critical culture. That gives us a slightly different perspective to maybe a few other creative directors who you have in the issue.

Rory: We’re interested in constructing narratives in all forms and all approaches. We love when narratives are taken out of context or are placed in other contexts. A film still with subtitles is such an amazing vernacular because you really appreciate the image of that moment in a film. It feels like a discovery: you discover the relationship between this subtitle and the image. It’s beautiful because it wasn’t designed – it just happened. That’s something that we really love. If you Google Godard or nouvelle vague, you find so many beautiful stills, and often they’ve been put into a sequence.

‘John Baldessari is the master of the word and the image, and how the relationship between the two can create a powerful message.’

Thomas: Chris Marker’s La Jetée comes to mind, obviously. Another question: do you find restriction interesting or even necessary for you when it comes to creative work?

Rory: We love it. Without constraints there is no game. We’re very interested in the constraints that exist, but also the constraints that exist within our conceptual methodology.

Thomas: How do you build self-imposed constraints?

Rory: In many ways, you develop them. We work a lot through metaphors and we like to think of what we are making as a kind of performance. We’ll develop a situation we have in mind, which has constraints within it. It’s like a stage in a theatre, which obviously has many constraints; it’s very much about that defined space. We work a lot with the imaginary in that way; we develop metaphors that have constraints. We also are really interested in the way in which predefined systems are set up. In fashion there are many. The industry has all these systems, like lookbooks or campaigns; it’s full of them. If you can start to, in a sense, dance with these restrictions, and find ways to weave projects into those situations, then you can on one hand meet the requirements, while actually doing something different.

Thomas: Nietzsche said that liberty is like dancing in chains, which I think is a splendid image.

Oliver: That’s a nice quote.

Rory: I’m going write that down!

Thomas: [Laughs] I think it’s a beautiful quote. I haven’t thought about it in a while, but it came to me listening to you. What in your eyes constitutes a good fashion image or even more widely, a good image?

Oliver: One thing we certainly try to avoid is simply adding a layer of decoration to something. The work shouldn’t be decorative; it should add an essential quality, and a meaningful purpose. If the image comes from an idea, then I think it has a chance of being a great image.

Rory: There’s also a heavy aspect of rationality in making images, too. The fact is that many things make an interesting image, but ultimately, I find the idea is an interesting way to define it. An interesting image can’t feel as though it’s been too hard to create; it has to feel of that moment. It has to be uncontrived.

Thomas: It needs to look graceful.

Rory: Yes, it’s graceful: it just happened; it was that moment. We work conceptually to create space in which we can create improvised situations. We don’t like to be on a fashion shoot where we’ve had to be very specific about the particular shot that we’re trying to get in advance. That feels contrived to us. We want to see what happens in that moment.

Thomas: Do you have a lot of commercial clients willing to embark on that ‘adventure’ with you? It must entail them being ready to embrace things as they happen, rather than anticipating exactly what will be produced?

Rory: We do, but I don’t know if that’s because we’ve always had that kind of willing client or whether we managed to find a way to get them to agree to that. Matthew Williams [of ALYX] is a fantastic collaborator; we work together a lot, and we’ve made a lot of fashion imagery together. He just totally trusts us at this point, because we spend a lot of time on the presentation of the overall concept of ALYX. It means that by the time we get to a shoot, we all know.

Thomas: So you work with words, not with images, when you’re explaining to your client what it is you’re looking for?

Oliver: I know other art-direction studios really seek out the perfect image reference, but we don’t do that. We try to articulate an idea, and so of course, bring in image and textual references. We write a lot to communicate ideas.

Rory: Unless the concept is, of course, to recreate an image, which can be a concept, too. A literal concept.

Thomas: Was there a defining image or reference that you look back on as having being instrumental in projecting you toward a career in art direction and creative direction?

Oliver: John Baldessari is not from a fashion background, but he is like the master of the word and the image, and how the relationship between the two can create a very powerful message. He is a major influence for me; it’s amazing conceptually, and there’s also a healthy dose of humour.

‘An interesting image can’t feel as though it’s been too hard to create; it has to feel of that moment. It has to be uncontrived to be successful.’

Rory: We discovered conceptual art when we started to collaborate at art school 20 years ago. Joseph Kosuth was key with his ideas that semantics and semiotics describe and construct objects, like the definition of a chair, the image of a chair. It’s very much part of our practice, conceptual art, conceptual thought. We really are in that lineage. We naturally think that way.

Oliver: If you look at an artist like Sol LeWitt, for example, he actually never made the work himself. He would plan it and then he would create the instruction to make it, which meant that whoever was taking it on could deliver it. In some ways it’s a little bit like brief making, and as art directors, we spend a lot of time making briefs, so that the people we collaborate with have a structure to their work.

Rory: We also spend a lot of time designing methodologies. Branding doesn’t actually exist; it’s really just someone saying to you: ‘Can you give me proof that we will be working together in a consistent manner?’ That doesn’t even need to come through form, though. It’s really about designing a conceptual system and designing a methodology.

Oliver: We are always creating an image to go somewhere. Whether a publication or a book, and we also have an imprint. So we’re always thinking about how what we produce is going to end up. When working on an image for a brand, for example, we’re thinking, where is that image going? Is it an editorial? A book? A campaign?

Rory: That’s something that we design. With ALYX, for example, we created a series of books called Preparation, one of them is a chapter in a season, and the activity that happens in and around the collaboration. It’s something we publish that brings a cultural context, and it’s made for less than the lookbook that used to be produced. It has nothing to do with looks, rather it’s part of the space we designed for how the brand communicates and works.

Thomas: What part of what you do is purely non-verbal intuition and what part is conceptualized?

Rory: We basically have intuitive starting points to everything. Then we try to find reason based on that intuition, and that reason helps us to work with others, too. Because you can’t just cruise up to Jonathan Anderson and say, ‘Hey Jonathan, what we’re working on now, we just felt like it and it felt good!’ You have to bring reason to your intuition. That’s how creativity works, isn’t it? If you think about being a theatre director, you might have a feeling about a performance you want to create, but you need to give instruction to your actors, you need to think about the lights. You need to articulate your vision.

Thomas: That makes sense. In general, are you aiming at a niche audience of insiders or do you prefer appealing to a wider audience?

Rory: We are not frightened by large audiences or global anything – but we are frightened by bureaucracy. We have to find our way in, in the right way. We only really work with the owners of things. So if Giorgio Armani called us and said, ‘I want to work with you’, then great. But it has to be the owner.

Thomas: Which person in the fashion industry do you most admire and why?

Rory: There are all the classics and I’m sure that’s what everyone says. I mean within the fashion industry I really respect Miuccia Prada, and Rei Kawakubo is great. They are not always about fashion, fashion, fashion, but more about fashion as a platform for expressing ideas. They both did that so successfully and also without losing integrity. They have a kind of myth.

Oliver: There’s Yohji Yamamoto, as well. What I like about his work is that he’s not doing whatever the market wants; he has a vision. He’s essentially playing with the same idea, the same silhouettes, the same materials, the same colour palette. He’s just evolving beautiful expressions of an idea over a very long career.

Thomas: Speaking with you, I get the feeling that fashion culture is not something that is necessarily a huge and constant presence in your minds. It feels like there’s a drawer with fashion and sometimes you look into it because it might be handy or useful, but it’s not like you’re engulfed in it at all. Am I wrong?

Oliver: Fashion is an amazing platform; it has a huge visibility. So, while we’re not embedded in fashion culture, we really appreciate the opportunity that it provides us.

Thomas: As things gradually return to some level of normality, will your impulse be to explore notions of fantasy and escapism or will you be more inclined to double down on realism and documenting the moment?

‘You can’t cruise up to Jonathan Anderson and say, ‘Hey, what we’re working on now, we just felt like it!’ You have to bring reason to your intuition.’

Rory: Realism! I mean you can tell by the piece we made for you. There’s an element of realism that, of course, doesn’t turn its back on what imagination and fantasy can do to realism.

Oliver: We’re interested in confronting it rather than escaping from it.

Thomas: Are you itching to get back to the pre-Covid-19 processes?

Rory: There are going to be some terrible constraints, financially especially. Which will be tedious and a shame. Negotiation is not the best part of any project, so we hope that doesn’t become a major issue. I don’t think it will go back to how it was, though. Before it happened, we were really in the flow of the fashion calendar for a while – going to the shows, going to fittings, you know – and it got a bit boring. Everyone we are speaking to – all our clients and collaborators – is sort of admitting that. It’s very unlikely that we will just go back to that. There will be the opportunity to rethink. For example, we will have to see if the things we’re currently making still work. We are making JW Anderson’s show, which will now have to be handled in a completely different way.

Thomas: I suppose you can’t tell me about it right now.

Oliver: We know where it’s going but we’re not allowed to tell you!

Rory: It’s a real opportunity, because in the end there’s not a lot for a creative director or an art director to do for the fashion show anyway.

Thomas: You could do the decor, you could do the set, which I think is desperately missing from fashion shows.

Rory: I agree.

Thomas: Creative directors should be a lot more involved in that part of the industry. Seeing the filmed versions of these huge, massively expensive shows is dispiriting; they’re so empty. Artistic directors should start making these films now.

Rory: Definitely. That’s an exciting aspect for sure. At the last ALYX show, we actually developed a really unusual project, which, now I think about it, wouldn’t have happened if there hadn’t been a show. We developed a new hair and make-up mirror with [hair stylist] Gary Gill, Alexander Sherborne, who’s an industrial designer, and Matthew. That was really satisfying, then we did a shoot using the mirror after the show with all the models when they came and sat down; it’s going to be published in Another Man. What we’ve begun to realize is that there were different ways to feed off the show moment. The book we did, Preparation, is also a result of that. Behind-the-scenes photography since Juergen [Teller] and Helmut Lang and that whole moment has always been an inverted kind of thing. For the shows, it would be great to get into the concentric circles that exist around the presentation. Both on a level of what you were saying and how we mediate it, as well

as everything else that happens. The potential is considerable.