In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘It’s not super hard to make “pretty”,

it’s super hard to subvert and trans-

port it to a different kind of place.’

A conversation with Patrick Li,

21 May 2020.

Thomas Lenthal: Could you talk me through the portfolio?

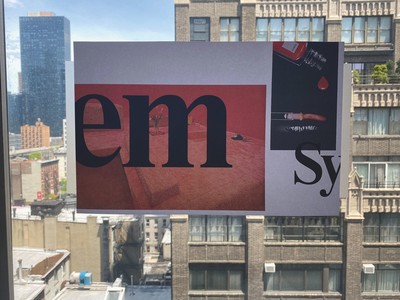

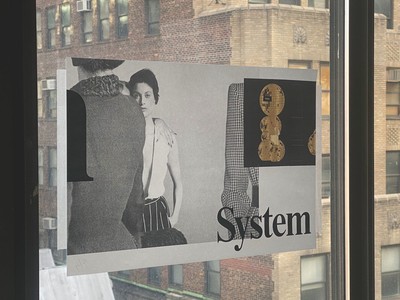

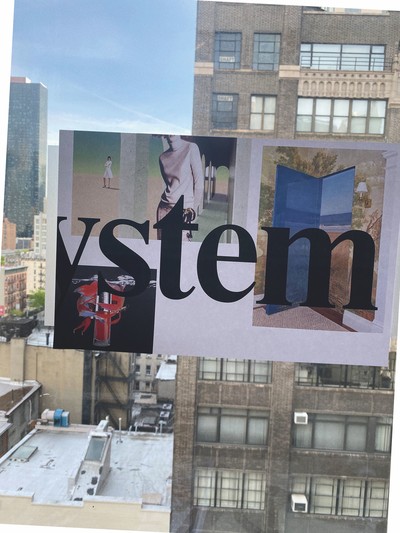

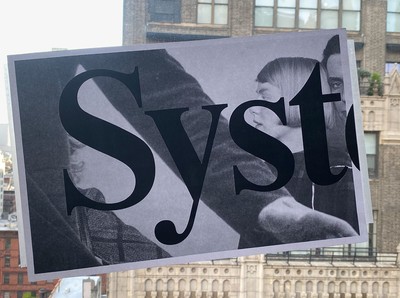

Patrick Li: I took a step back and thought about what it means to work during this time, and how lucky we are that we can do this despite the chaos. I thought maybe it was a good time to be more revelatory or transparent with the process. We spend so much time making things that never see the light of day, so one idea was to reuse these layouts that we had made over the past 15 to 20 years. They support projects that never really surfaced, so I wanted to bring those to the forefront.

Thomas: What are they exactly, like presentation material?

Patrick: I was thinking about images that I could work with. Instead of having a photographer supply images, I wanted to turn the tables and have a photographer rework material that originated elsewhere. The references in what I submitted are very common, but they are chopped up and reassembled, and that in itself was kind of fun. The twist here was to have a photographer re-photograph them. This era of working with reference visuals is simultaneously constrictive and liberating. It’s absurd how specific a lot of them have to be now; you have to show the client exactly what you are going to do. There’s no more creating on set. I find that a little disturbing, but it is also partvof the reality, so in the studio we make a point of exploration and fun.

Thomas: On certain accounts, do you tend to deal almost exclusively with middle management?

Patrick: It’s the chain of command, totally. There is a culture of fear. With more and more corporate clients it is definitely like that: the marketing person does not want to get in trouble. That is the reality of the structure today. It doesn’t allow for pure expression unless you have a direct link to a designer, and that is rarer today. You no longer really work for someone. I think that this limitation has deterred a lot of possibilities. And it’s not about the size of the business, it’s really about the layers of supposed decision-makers. When you were talking about the middle men, it’s those different layers that can be the block.

Thomas: It has made the playground smaller and smaller.

Patrick: Not just the playground, but the structures: this is all you have, you have to work with this. A lot of it is second guessing, too, like, ‘Oh I think this will work.’ That may be a natural part of a creative process, it should be done more instinctively, and sadly, it’s not. But I do feel there is a possibility to be more genuine or more real now. This era expects that.

Thomas: What do you find intuitive and what do you overthink in your work?

Patrick: There are different approaches to that. Either I consider myself as a service provider – which I think is a different approach to many colleagues or other people who I respect – and you want to help direct the conversation. That is my intuitive approach to solving a problem. There is always an issue that needs to be resolved and in that case I really like working on strategy rather than pure artistic expression. Instinct is my normal go-to. That means considering what the task at hand is, and how best respond to it, or how I can express myself totally. I’m not going to send a sketch and say this is the answer. I know that many people do, and they are solutions, just not the ones that come to me.

Thomas: To find relevant solutions, you need to be able to have a conversation with whoever you’re working with?

Patrick: Yeah, I mean, you hope you can. It is so rare.

Thomas: Do you find restriction a useful or necessary thing when it comes to creative work?

Patrick: Boundaries help to define what the challenge is. I find reacting to boundaries one of the most enjoyable activities somehow, trying both to comply and to skirt around what the boundaries are and why they exist. Often they are completely arbitrary, and I enjoy getting into that moment of dialogue with whoever is doing the commission: why is that what you need? Obviously when it is for a fashion brand there are the image-building and pragmatic issues, like creating desire and sales. In general, boundaries for me are not really restrictive; they liberate me and they are an enjoyable part of the process.

Thomas: Since Covid-19, a couple of hundred thousand people in the industry are all experiencing a new reality. Do you think they’re enjoying this change of pace or are they traumatised?

‘Many fashion images are too ahead of their time and have too much going on in them. But some mediate that balance perfectly and become forever images.’

Patrick: Obviously, context is so critical. You are used to one thing and then you are completely disarmed the next day. Isolation feels like a more emotional time than before. So I think New Yorkers must be reacting in a very specific way. In the city, you’re around millions of people all the time, but that in itself became such a huge liability. It’s been such a radical upheaval of our existence; things have completely changed now. Exchange is in the very nature of collaboration, but the foundation of that exchange is now completely different, having gone from in-person to digital exchanges. We are all talking through texts and FaceTime and Zoom and while you are obviously missing the humanity, the exchange is still there.

Thomas: I imagine the differences must be even more striking in New York.

Patrick: I am on the tip of Long Island and there is nobody. I have friends still in their apartment in the city and they still need to go to Whole Foods and wait in line, six feet away from someone else. It’s not really like that where I am. This experience is so personal and about where you find yourself. When it comes to work, it was fascinating to see how we found resolve in how we approach it. At the magazine at the New York Times, we are still having regular meetings, and we have the support of a very smart, large organization with the structure to send you a computer if you need it. It’s remarkable.

Thomas: I was speaking to other American art directors and they were saying they were just getting used to the basic and essential stuff. Also after two months, you really get into that completely different zone and for some people it is highly enjoyable. Do you miss the before?

Patrick: There are certainly aspects I miss, but it depends on what you find meaningful personally. Part of the reward of work for me has always been to be with a bunch of people and create, but since lockdown, I’ve been finding it really, really gratifying to have a work meeting and then go outside and plant some plants. I have never done that before and it’s awesome. I’m really surprised. I’m like, ‘OK, I’m going to go outside and pull weeds for half an hour before my next meeting.’ It’s a weird reset like nothing I’ve ever experienced before. It doesn’t seem real, yet I know it is, and I am having a hard time resolving that because who knows how long this will be? It’s pretty enjoyable right now though.

Thomas: What constitutes a good image in your eyes?

Patrick: I think the enduring image for me is the most successful: one that triggers a reaction that goes beyond the standard emotional response. It is an image that respects a certain moment of creation somehow, but also propels things forward. There are a lot of images, in fashion specifically, that are too ahead of their time and have too much going on in them. But there are some that just mediate that balance perfectly and become forever images.

Thomas: What you’re looking for is timelessness?

Patrick: It’s not necessarily timeless in that sense, but it is enduring. There is a difference in the lifespan of an image. Some are more immediate, but that is not to say that they are less important than an image that has a longer life span. How you define a lasting image, and how you make one, are two different things. The frequency of how often you see a certain image is one of the key factors. I’m talking about the duration of how long it is allowed to exist or be at the forefront. The time to make an image is of course completely different now. We don’t have time to craft. While it’s hard to know if an image will become enduring, you can see a magic through the lens of the photographers you work with. There will often be a ‘this is it’ moment, a spark that can help create a more enduring image, separate from the marketing brief. Often, though, things are just not given the chance to survive out there in the world, but that’s a whole other question!

Thomas: It’s interesting because we work in an industry where seduction is everything. Fashion photography has to be immediately attractive, but then also endure?

Patrick: Yes, but I don’t know if it isn’t more attractive or provocative, like you want to seduce but also create a repulse-and-attract dynamic. I always talk about things having a sort of vibration between good and bad taste. There are moments when we’ll work on something and be like, ‘That is too pretty.’ That is what I call the tyranny of good taste. Once it happens, it’s like the end of the game. You’ve got to subvert it somehow, that’s the exciting moment for me. It’s not super hard to make “pretty”, it’s super hard to subvert and transport it to a different kind of place. There are different factors that can provide that subversion. There are a lot of different ways of arriving at that place. Sometimes it’s staying up all night, like, the deadline is tomorrow and now I have to finish this. That happens to me a lot. Like, I’m so tired, just do it! That obviously changes as one gets older, but I have always worked that way.

‘You want to seduce but also create a repulse-and-attract dynamic. I always talk about things having a sort of vibration between good and bad taste.’

Thomas: With hindsight, was there ever an image, reference, person or moment from your teenage years that was key to you having a career in fashion art direction?

Patrick: It was really through music, where you would get these moments when design, photography, language, word choice, all united perfectly. I didn’t really know whose role it was to help those things come together. Because it’s not just solely a graphic-design challenge. It is about aligning all these different energies that could be at odds with each other but somehow come together in that moment; and that’s just really cool. For me, that was [record label] 4AD, where it was like, ‘This music is so insane, and this album packaging and the titles and the meaning is mind-blowing.’ It was just a very specific aesthetic position that felt passionate; someone had a point of view and really went for it. I would say the same thing about other kinds of aesthetic positions that were at odds with what I felt my values or identities were. Like Led Zeppelin, for example, I love some of those album covers. There were also punk or protest graphics, which were so unapologetic about all those positions and which I really admired. After a while things can sort of bleed together and lose their potency, but I really love those genesis moments, when things really came together. They provided some structure for me to aspire to.

Thomas: How old were you when you were enthralled by those Led Zeppelin covers?

Patrick: I was maybe late to the game, but at the end of high school, early college. I’ve told this story before, but when I was in college working at this magazine store, I realized that, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s a Vogue in Italy, did you know that? How cool is that!’ Maybe Fabien [Baron] was there at that point. I also discovered this magazine called Emigre, which is a graphic-design magazine; it was so amazing. They said their next issue was going to be a special 4AD issue, and I was like, ‘What? How is that possible?’ I wrote them a letter on a photocopied Comme des Garçons postcard saying, ‘I love your magazine, can I come work for you? Do you need anything? You know, I am a big 4AD fan.’ Nothing, no response and the magazine came out and I was like: fuckers. But then I got a call the next day and they said, ‘We were busy with this issue, but now we do actually need some help. Can you come and help us shift these magazines?’ So that was my first real job where I was exposed to a world of graphic design I had no idea existed. I got to New York after that, and there was a 4AD Emigre poster up at the Interview art department when I started working there, which was really weird. So it’s a very linear path.

Thomas: Do you prefer working for a niche demographic or a larger audience?

Patrick: There are always discussions about whether you should reflect an audience or do you lead an audience. Other magazines out there reflect, but that is not what Hanya [Yanagihara, editor in chief of T] wants to do with T. She really wants to provoke and lead, and is leading through diversity and a lot of gender fluidity. That is really a large part of what the magazine aims to do.

Thomas: Which person working in the fashion industry do you most admire, and why?

Patrick: It would be a cross between Margiela and Rei Kawakubo, for being able to do what they do and making it successful.

Thomas: And being so elusive.

Patrick: And being elusive. That adds to a certain kind of mythology, but it is more that you judge the person by their work, and you can always tell who created it and what it is. You might not understand it, but I think that can be even better somehow. They have made huge businesses out of these things that are so specific. That is remarkable.

Thomas: Can you describe a professional disappointment?

Patrick: It would start with a lack of humanity in the fashion world. We all know it’s a competitive industry for brands and for everybody, and I’m sure that even at a dentists’ convention there’s a lot of competitiveness, but sometimes it can feel like there are a lot of crazy people who do things in fashion that they wouldn’t be allowed to do anywhere else. It is an industry that really celebrates and even mythologizes bad behaviour and cruelty.

‘How long have we known each other and never really had a chance to talk like this before? This Covid situation has enabled some rewarding things.’

Thomas: It feels to me like this whole ethos of cruelty is slowly dissipating.

Patrick: For sure. Fashion at its highest level takes its cues from contemporary art, for example. Most of the contemporary artists who are relevant and the most meaningful today work their asses off. They have an instinct to create, but the way they make their business or practice, they’re not like: ‘Look how easy this is.’ The most successful designers today are the ones who work incredibly hard.

Thomas: To finish our conversation, what will you take away from this moment and is there something that will continue to resonate when things start to subside? Are you itching to get back to the pre-Covid system?

Patrick: I can’t imagine going back to pre-Covid. I think this is a radical shift in what’s happening with our culture right now; it’s not like an isolated thing. I mean 9/11 was huge for us and did impact the rest of the world, but what is happening now with the pandemic is truly a global incident, which feels really transformative. It would be naive to think we can just go back to a time before this happened. I do feel like there has been a greater awareness of, I don’t know, the human connection. It’s weird because with all the digital stuff that was happening pre-pandemic, everyone wanted to be engaged experientially, but that is obviously a very different conversation today. Suddenly the digital can spark a very emotional response, much more so than normal. There are things you see where you are like, ‘Wow, that is really beautiful and touching or really fucked up and very disturbing.’ But it has been so much more emotional than before. I think that that awareness is going to endure.

Thomas: This change of pace feels a little more human somehow, so we might have trouble readapting to that culture of everything being hectic and hysterical somehow.

Patrick: The circular repetitive act of working pre-Covid – getting to work every morning, having lunch, going home – I think is gone. It’s a different kind of pattern now and we need to adjust to it. Now I can take a break and go pull weeds, which I really enjoy! I find myself being more productive in a certain way, but other people are more frantic. Did I e-mail in time? Like, you’re at home, you should be working, what else are you supposed to be doing anyway? We are all trying to establish what our routines are, which is a very human response. You need that structure or you don’t – it depends on your personality or psyche – but I do think the process has completely changed. You can take more time to have more meaningful conversations. Now there is actually time, you’re not snatching a few minutes between meetings. Like this – this is so rewarding, how long have we known each other and never talked like this before? This situation has enabled your issue to happen and that’s a whole thing. Actually, that is why I have been working with Richard Burbridge to do this portfolio. I had always been a fan of his work even before he moved to New York. I remember at Self Service, I wanted him to do a still life and he said, ‘This is the lighting and the retouching’, and I was like,

‘Dude, we can’t afford any of that, so let’s just try with the flashlight and see what happens.’ And it was such a great story; it is still a nice reference. It really did become a part of his language, and it came out of a spontaneous discussion. He didn’t know I was doing this project with you, but I said it would be a nice way to complete the circle, to come back to this idea of what a fluid collaboration can be. He didn’t use a fancy camera; he wasn’t in his studio; he didn’t have a team of assistants – it was just him taping stuff to the window. It was so cool for that to come around, and it’s all thanks to you.