In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

In early April, we sent the following request to 17 leading art directors working in the fashion industry.

We’d love for you to conceptualize and deliver a fashion portfolio with your available means and from your current location. You would be entirely free to work with any partners, and to select any brand(s) you would like to feature in the portfolio. The exercise is one that innately addresses the current restrictions on collaborative work.

Just prior to sending out that message, we had asked ourselves a question that remains as bewildering today as it was when fashion’s capitals were first entering lockdown: in a world of Covid-19 restrictions, how can you create fashion imagery that often requires in-person collaboration, international travel, shipping clothes, and an often significant budget?

We decided to let the industry’s art directors work that question out for us. In doing so, commissioning a collective body of work that feels both adapted to this uniquely curious moment and which acts as a mirror to its creators. Each of the portfolios presented over the following pages reveals the personality, idiosyncrasies, background, working processes, address book, and creative impulses of the participating art director(s).

‘So much of a project’s success is

about the conversations you have

with the people involved.’

A conversation with

Veronica Ditting, 14 May 2020.

Thomas: Thank you for all your hard work. Your portfolio is a wonderful addition. Would you like to talk me through it?

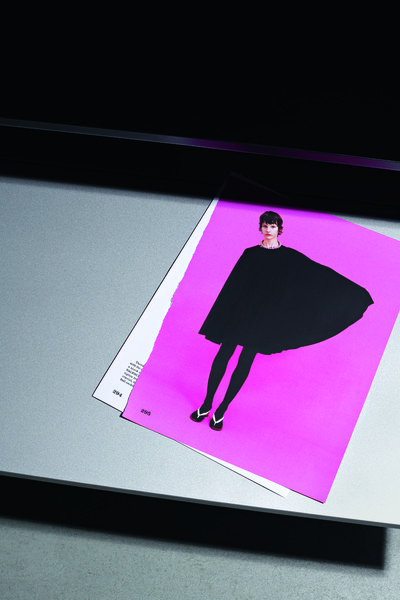

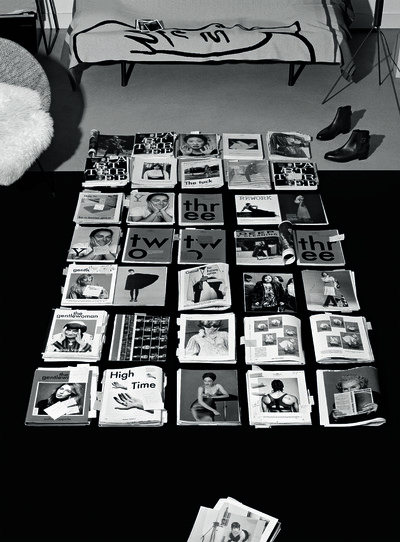

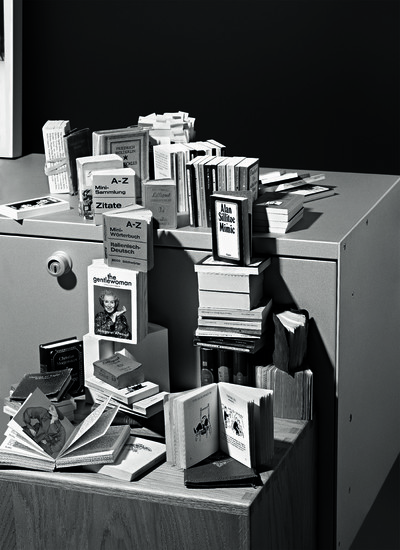

Veronica: When you got in touch, I thought, ‘How can I participate in a way that isn’t just pulling up archive work and putting it on the page?’ Funnily enough, before the lockdown hit, we were in the midst of a huge spring clean of the studio. It’s something I’d never gotten around to doing since we moved to this particular studio in the Barbican, because we’ve been incredibly busy and there is no time to stand still. For the portfolio, I thought it would be nice to give a little peek into my world and my approach, but rather than just showing work we’ve done, I wanted to make it like a diary-tool-book-portfolio. I thought I could try and shoot it myself, but wasn’t sure about my technical capabilities, so I called my neighbour and friend Matthieu Lavanchy. We really took our time to build it up. Some pieces are more straightforward, like maybe the Hermès beauty thing, and then some are a bit more mysterious, like the ring with a moon face. That’s something I purchased last year and the kind of object I really like. It was an opportunity to show how I work. Like, the tape is so simple, but image editing is such an important part of what I do, and we do endless amount of dummies, so it’s something I actually use all the time. I also wanted to do something with a bit of humour – and my slightly neurotic and specific office supply needs are always a bit of a running gag with my colleagues. It was a little bit of a humorous take on that, but also showing how I work and with which tools. Everything in the image is a personal belonging and from the office, and then, of course, Hermès was kind enough to send the lipsticks that Pierre Hardy designed.

Thomas: How do you cope with restrictions in your work? Do you find them useful or necessary in the creative process?

Veronica: If the restriction makes sense from the start and I understand the parameters, I actually quite like to work like that. Sometimes they can also guide you to a specific solution. If it’s a budget, time or technical restriction, you just have to do what you can with the parameters that you have. If they’re the result of someone’s personal tastes, though, then that I find a bit problematic. If it comes out of nowhere, and suddenly all these restrictions are lined up, then you’re like, ‘Where is the space within this for me?’ That can, of course, happen. If I understand where the restrictions are coming from, then they can be creatively positive, as well. A stupid example, maybe, but when I studied graphic design at Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, we only had an A3 black-and-white laser printer. That was our restriction in terms of making publications, but it guided you to find specific solutions.

Thomas: You also need to be able to have an honest and real conversation with the client…

Veronica: So much of a project’s success is about the conversations you have with the people involved. If you are all pulling in different directions or have a different work ethic, then it can become a damage-control project. That can happen! I’ve also had a lot of projects where it was a very direct conversation and really about building up a working relationship. When I commission photographers I’m ideally looking for a long-term working relationship with someone, and the same with clients or collaborators. I want to create something we can build on, rather than a one-off thing.

Thomas: What in your eyes is a good fashion picture? What do you for?

Veronica: It depends what it is for, fashion or portrait. In general, I am much more drawn towards fashion images that, even if it’s a professional model, almost feel like a portrait of a person.

Thomas: I agree with that. Fashion pictures should first and foremost be a great portrait, the rest is…

Veronica: …the ingredients and how they come together. I also like it when the fashion and the styling takes more of a solution-based approach. We approach certain stories in The Gentlewoman a little bit like that. We did a story, which we shot in Denmark with Julie Greve and our fashion editor Eliza Conlon, featuring street-cast women. It was all about outerwear and jeans and it was nice to have this moment in the magazine where you just make a suggestion about what you can do with what you already own. It was a little bit less product-driven, like a sort of creative lookbook.

‘In general, I am much more drawn towards fashion images that, even if it’s a professional model, almost feel like a portrait of a person.’

Thomas: The Gentlewoman does have this notion of the how-to guide, to which you have brought a new level of sophistication and irony. You have sort of revived the notion of what’s practical. When I was putting together the group of art directors for the project, I had a really hard time finding women. Why do you think that is?

Veronica: That’s a good question. There are some, but of course not as many as men. When I studied, there were so many women around, but they all sort of disappeared! It’s really sad, and I often get asked that when I teach: how come all the really talented women disappear? I am convinced it’s because the opportunities for female professionals are different from those for men, even if it’s hard to put my finger on exactly why. Maybe it also comes with the whole idea of a creative director being strong-willed and so on, and perhaps sometimes women are looking more for dialogue. Maybe that plays into it. But I also think very often women are simply not given the same opportunities, so they can’t grow into that position. But it’s a good question. I can hardly answer it. What do you think?

Thomas: I come from a different century! Back then, a creative director was supposed to have a lot of interaction with the actual printers, and that would be a very hardcore blue-collar environment… Perhaps that technical element made it something more associated with men, but that can no longer be the reason. Then, within a fashion magazine, the only male presence was probably the creative director. I remember working in fashion magazines back in the 1980s and 1990s and I was probably the only man on the floor, which is quite something. It is almost as if back then, just like with nurses, it was an essentially female endeavour, except for the creative director, who was a man.

Veronica: You know, the whole thing you were saying about the technical aspect of the job – I studied in Amsterdam and there are a lot of very established female graphic designers in Holland. Out of all of the countries I have lived in, it is the most fairly balanced between men and women, and it never seemed like a disadvantage to me. I know that the printers are probably scared now when they know I’m coming! I don’t think it is the technical aspect, though; I really think it’s that the path towards becoming an art director or creative director is not something straightforward. It’s not something that you can study for. That, for me, links up with this idea that a lot of female creative directors just don’t get the same opportunities as men. If you also go through the list of people on panels and at lectures and talks and so on, it is primarily men. It’s shocking to me that either the people who organize these things don’t know anyone or that they don’t do enough research beforehand. It’s something that some organizers don’t reflect upon enough and hopefully that is changing a bit more and people are a little more aware of it.

Thomas: One of our colleagues suggested that maybe being a creative director is a very geeky thing to be.

Veronica: Sure, but women are geeky! Women have become geeky. I mean, did any women that you asked say no to doing this?

Thomas: I asked Ronnie Cooke Newhouse, and she said yes, in principle, and in the end couldn’t fit it into her schedule. There’s another woman, Lolita Jacobs who is part of the couple called LJBTN, but that’s about it.

Veronica: That’s crazy.But for me, really, it is opportunity and visibility that are the problem.

Thomas: That might be so. Next question: what in your work is most intuitive and what part do you tend to overthink?

Veronica: That is a good question. You need a lot of intuition to be on set and working with someone, and you have to be able to let the photographer do the best he or she can do within his or her skill set. So a lot of what makes a good image is intuition. The same is true for who to ask to work on a project or for images. If you click with someone, that is all pretty much intuition. Still-lifes are less intuitive for me than a photo with a model or a sitter; I might have to think more about them. What part do I overthink? I definitely spend a lot of time, once it’s all done, in the image edit, seeing how it all connects up. I always do it, then look at it the next day, go through it again, check the sequence again. I keep reworking and reworking, if it is a publication. Graphic design I don’t overthink so much any more, because compared to creative direction, graphic design is so easy! I definitely take a lot of time to really mould everything into shape and place.

‘Opportunities for female art directors are different from those for men. I often get asked when I teach: how come all the talented women disappear?’

Thomas: Did you strive to be different from a young age?

Veronica: God, no. Not that I can think of, but as a small child, I definitely had an obsession with images, though I wasn’t aware of it. I was born in Argentina and my grandmother would always tell me many years later that whenever I went to visit her, the first thing she had to do was pull out a box of photographs. Even when I was two or three years old, I was obsessed with…

Thomas: …with editing family pictures!

Veronica: Apparently so! I had no idea what the profession of creative director was when I was younger or when I was a teenager, but I definitely had a huge interest in art and art history. I had an amazing teacher at high school and he really taught us how to look at things, how to interpret them, and how to fact-check things. Very German! But I never had it in mind that I had to be different. I don’t think that really crossed my mind. I definitely had an affinity for visuals from a young age, though.

Thomas: When did it become clearer that this is what you wanted to do?

Veronica: When I was about 16 or 17; that was when I had that amazing teacher, Herr Nohl. I wasn’t quite sure how the profession really worked, but started to think about whether it should be graphic design or something else. I actually started with industrial design, but to be honest, I hardly learned anything. I still regret doing it, even if it does sometimes come in handy, like when I design exhibitions. Then I switched to graphic design, and moved from Germany to Amsterdam to study at the Rietveld Academie. I had met someone who was studying there and everything that he told me about its approach sounded so much more intuitive. In Germany, graphic design was very much more service-orientated. A lot of people who graduated would do branding projects for imaginary clients, and I just thought, ‘I don’t know if I can do that.’ I guess I have a curious mind and I really longed for a dialogue with the people around me, and that wasn’t really facilitated in Germany. It is a very different mentality in Holland; it is much more creative and expressive.

Thomas: So, how did you get to fashion?

Veronica: I started working in fashion more when I started coming to London twice a year for the magazine production. Slowly but surely I had more clients here. If I had stayed in Amsterdam, then I definitely wouldn’t be doing the same jobs.

Thomas: Ideally, do you prefer your work to appeal to an in-the-know niche or a wider audience?

Veronica: There’s a balance, I guess. I mean, people who are not in the know might not be able to put into words why something does or doesn’t work, but they might be able to feel it. The magazine, especially, has a wide audience and its strength is that it is not just focused on the fashion industry; we get feedback from people from so many different backgrounds. The most important thing for me is that the magazine has a point of view, and an interest that will engage for a longer time. It’s a biannual; each issue needs to be able to be on newsstands for half a year. But it is a balance. I think sometimes brands are a bit, like, ‘Well, our clients won’t understand this’, but you have to take them on a journey; you need to be guiding them. It shouldn’t be something where you don’t understand what the picture is about any more, but also it shouldn’t be anything that doesn’t have fashion credibility. Ideally, you can have both audiences. The funny thing, though, is that because I do both creative direction and graphic design, I can have quite different peer groups. My peers from the fashion world don’t overlap with the design peers, and it’s funny, they’re very different groups. The geeky designers come from a different background!

Thomas: The 20th century at its best sometimes tried to create what in France in the 1960s was known as ‘beauty for all’, which is probably an old Bauhaus philosophy, too. Beauty using industrial means to target the entire population.

Veronica: I don’t know if you are pointing to this, but through social media and greater online connections, people tend to be pulled in a similar direction, aesthetically. I sometimes find that incredibly frustrating.

Thomas: Does that create a sort of international lukewarm taste?

Veronica: Exactly. There’s nothing wrong with it, no tension, no fashion credibility. It’s probably good taste, but it’s not personal and not expressive and not much more than superficially interesting.

Thomas: Another of our peers said that there was a time when you could create long-lasting fashion imagery; fashion images from other decades seemed to have a lasting quality. He was saying that perhaps today given the inflation of image production, images tend to disappear into thin air. I thought that that was both a beautiful and a disturbing idea.

‘Through social media and online connections, people tend to be pulled in a similar direction, aesthetically. I find that incredibly frustrating.’

Veronica: Totally true. Some photographers shoot so much that what they do is sometimes great and at other times a sort of whittled-down version. On the other hand, given that they do so many projects, people might not pick that out any more. We work much more digitally now than even five years ago, but I am always struck when I see something on Instagram by a photographer and I think, ‘Oh, that is interesting’, then I see it in print, and realize that actually it was made for Instagram, not for print. I wonder if the thought of it being in print makes you take a picture differently.

Thomas: It might also be that the quantity of images produced these days in a commercial fashion environment makes it very difficult to refine things. One can no longer afford the luxury of actually spending the time needed to put things together. In order to produce so much, you need to resort to prefabricated recipes.

Veronica: Absolutely. I mean, there are probably campaigns still on people’s mood boards that were made in the 1990s, and they had a week or even two to shoot them.

Thomas: We had a week to do about 10 images.

Veronica: Wow, I mean, I have never experienced that!

Thomas: The process was very extravagant. Then again I know photographers who are incredibly fast and yet very precise and specific, like Steven Meisel, who literally shoots in three minutes.

Veronica: Because he puts a lot of prep into it?

Thomas: When he arrives on set, everything is ready, and he gets it in very little time. I think he is probably interested in keeping some freshness in the process and not making it too tedious for the model. He is very interested in the relationship with the model.

Veronica: It’s true, you can kill a shoot before it actually happens. Managing to keep the energy on the shoot day, that is another instance of where that element of intuition comes in. Of course, our job is all about planning and thinking of all of the different scenarios and outcomes that could happen, and then showing people what the picture will hopefully be like. But sometimes you can also do that to such an extent that it leaves no room for the picture to have any energy, which is something I’m always looking for.

Thomas: Do you think that the near future will be more about escapism and fantasy or will you double down on realism and documenting the moment?

Veronica: At the start of all of this, I found it incredibly difficult to imagine what we would want to see come autumn, because of the mental state that I and everyone else was in. I would hope that it’s a sort of balance of the two. Reality is always very important to how I approach things, but then I do also appreciate things that are maybe a bit more, let’s call it, fantasy. It is so hard to say what even is to come. In the end, people are going to have to stick with their strengths, continue on that path, then adapt to the new situation – and hopefully do it with thought.