Celebrating 40 years of Paris couture’s discreet radical.

By Olivier Saillard

Photographs by Maxime Imbert

Styling by Camille Bidault-Waddington

Celebrating 40 years of Paris couture’s discreet radical.

‘I cannot judge fashion, whether yesterday’s or today’s, based upon my taste…’ Adeline André doesn’t always finish her sentences and it is in the silence of those ellipses that you suspect she is making excuses for the arrogant fashion world. She has navigated it alone and one day it may understand that it has always been dominated, if not ruled by her.

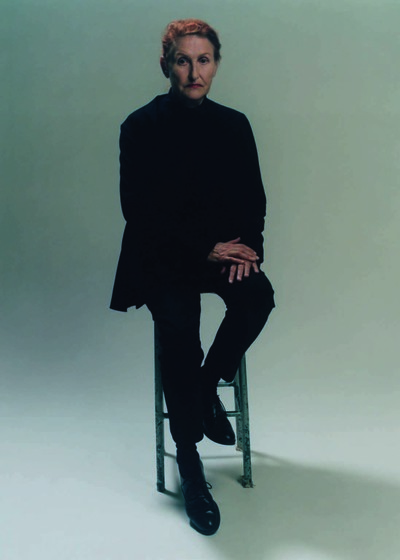

Sitting on a stool, her legs crossed, dressed in one of her celebrated ‘three-sleeve-hole’ blouses and a pair of plain white trousers, Adeline André welcomes visitors with movements of her head that feel like vanishing points and evasions. She has always been able to escape. The trajectory of her work has never been corrupted by any passing trend or the rise and fall of fashions. Since the 1980s, her gracious dresses, tailored in handkerchief chiffon and imbued with her carefully chosen colours, have stood apart from fashion’s overarching timeline. Both modern and classic – like all masterpieces – they owe their elegance to a Madeleine Vionnet-like refinement, but set themselves apart with a post-punk simplicity.

Her work is timeless and her own look is also from elsewhere: her round, Modigliani-like eyes, and her lab-assistant orange hair make her appear like a creation from the future. When she first arrived in Paris, Adeline worked nights in a convenience store and would devour science fiction. Her radical uniforms could still make her the heroine of those tales of other worlds. Back then, the young artists Pierre & Gilles turned to Adeline to handle the styling and clothes design that were key to them turning the Paris in-crowd into kitsch martyrs and saints. Alongside Maud Molyneux, the much-missed transgender journalist suffocated by salon couture, with Edwige Belmore, official queen of Parisian punks, and accompanying Elli and Jacno, musicians and creators of pop music à la française, Adeline André was one of those people who magazines at the time dubbed ‘modern young people’.

Was she ever really aware of that? Her choices seem to contradict both the eras she has crossed and other designers’ trajectories. Nothing seems to affect Adeline, a person for whom the terms artistic director or visionary simply do not fit. Adeline is an author, a fashion author, and her poems are her clothes.

‘What would be the point of me doing anything other than Adeline André?’ she asks, astonished, in front of another of these journalists who seem incapable of recognizing her true worth. Just as you would no more ask Sonia Delaunay to paint a different style to her own, it would be out of the question to corrupt the designer and push her to create anything other than Adeline André.

Olivier Saillard: Adeline, what was your family like growing up?

Adeline André: My father worked in finance; my mother was a voracious reader and extremely attached to our education. We used to pretend that our family was a sixteenth Scottish and a sixteenth Copt, but far from those foreign climes, we are actually genuine sedentary Parisians, attached to Chatou where I grew up and later the 11th and 17th arrondissements in Paris.

What did you study?

I lived in London for a while where I studied drawing, and then I began directly in the second year at the École de la Chambre Syndicale in Paris. We were taught prototype making and cutting techniques there. I also attended Salvador Dalí’s drawing classes. This was in the early 1970s. I remember going through the telephone directory to find the names of fashion designers who interested me and then calling them and setting up meetings. That was what happened with Dorothée Bis, which was run by Élie and Jacqueline Jacobson; they bought several designs from me back then.

What do you now see as your fundamental experience from that time?

Without any doubt it was the time I was lucky enough to spend with Marc Bohan, who was then at Christian Dior. I had contacted the head of personnel at the time and when I didn’t hear back, I rather brazenly decided to contact Marc Bohan directly. His secretary very kindly organized a meeting with him and when he looked through my designs, he pointed to a series of sketches of bags, jewellery and accessories. He liked them so much that he hired me for his studio. You have to remember that at the time, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, haute couture was absolutely not a sought-after discipline. It was seen as really old-fashioned; the young treated it with disdain. Marc Bohan himself used to say that haute couture was often more about performing orthopaedics: our main role was adapting the clothes to our clients’ bodies and shapes, which were completely different to the models’! Despite this faded image, that period was a genuine opportunity for me and real chance to learn about everything. We were only a few assistants – both men and women – locked in a studio shared by Marc Bohan and Philippe Guibourgé, his partner and collaborator. It was a veritable beehive. We were involved in every aspect of the house, from the design to the collections to all types of fittings. Serge Lutens would also regularly come around, accompanied by plenty of anecdotes, to test his make-up on models who wore white overalls; it was more beautiful than lacquer. I remember his good humour, which was such a central part of that essential period of apprenticeship.

When she first arrived in Paris in the early 1970s, Adeline André worked nights in a convenience store and would devour science fiction.

How long did you work with Marc Bohan at Dior?

Two years, during which time I was his assistant, notably for accessories. To structure and rationalize all his ideas for clothing, I reworked all the designs for the collections in a unique fashion that he absolutely loved: I took the sketches that we used as a collection plan, and which were later hung on a board, and I redrew each piece using a ruler. Marc absolutely adored that extreme geometric approach. I also spent half my time working on the lines run by Philippe Guibourgé, including Miss Dior.

When did you take the decision to create your own collections?

After working with Dior I joined style agency Promostyl where I put together trend books for manufacturers. I was also briefly Jean-Charles de Castelbajac’s right-hand and worked with him on those remarkable clothes he made using repurposed floorcloths and crêpe bandages. In 1978, I met István Dohar, my partner for life, who was originally from Hungary and had studied art in Switzerland. He pushed me to create my own collections and always to be demanding and a perfectionist when making the clothes. In 1981, we met a financier, Nicolas Puech, who supported the collections for nearly two years. Having decided not to carry on with our young company, the collaboration stopped and I’ve continued with István ever since.

How have your creations always stood out from the zeitgeist?

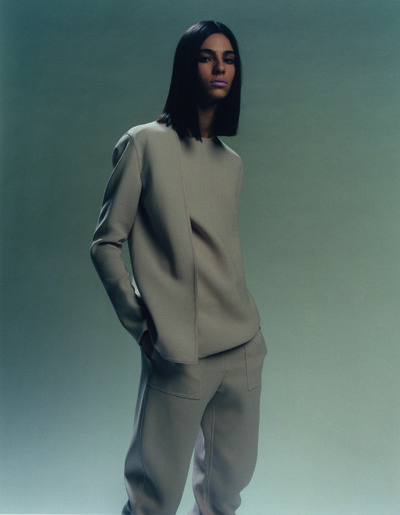

My first collection, Autumn/Winter 1981, was shown at the ready-to-wear salon. It was made up of pieces with three armholes, for men and women, in completely traditional fabrics, like sheets, flannel, tartans, Harris tweed, and camel hair. The collection received a great deal of press and lots of copies popped up afterwards. In the 1980s, padding and shoulder pads were everywhere, and they ended up looking like caricatures. Stretch fabrics were also beginning to invade. I wanted to oppose all that by paring back the clothing as much as possible. I took out linings and canvas interfacing, so all that was left was the ‘skin’ of the clothing in which a body could move around unhindered. Then, thinking about starched haute-couture clothing that looked like support cages made me want to shake out all artifice from clothing and keep only the essential. So in 1983, I naturally turned towards silk crêpe and silk satin, which at the time were totally old-fashioned and so regarded with a certain disdain. Cut on the bias, those clothes pushed me towards a certain simplicity; they were almost like draping. I’ve always continuously stressed cut and movement, and paid particular attention to details. In 1985, I made sweaters and outfits with rolled necks and hems, which were made to measure and ordered by more than a hundred people, notably Bettina, the famous model, who was a loyal customer from the beginning.

Your clothes might have sensible cuts, but the colour palette is explosively unique and contributes to the feeling of poetic calm in your collections. How does colour fit into your wider design world?

I have always wanted my clothes to breathe between the body of the wearer and the fabric. Prints and decoration can only weigh down that concept; only colour can make clothing that already feels light even more ethereal. Right from the beginning, many of my designs had no buttons, zips or straps, and they contained no synthetic materials. That made them precursors of the recycling movement: there’s no structure to be removed if the fabric is recycled. It remains true to its origins. Colours are the only possible observation. I invent them and I reuse them. At the École de la Chambre Syndicale, I put together a class about colour and I created a range of original colours for a Japanese fabric manufacturer. The past three decades have been totally directed towards techniques of looseness in clothing and the rise of sportswear does nothing to go against that trend. In that context, colours become a priority. It’s such a joy to seek the ascending and descending nuances of each one. Rarity comes not from an isolated colour, but from the environment in which it is set.

‘I’ve always wanted my clothes to breathe between the body of the wearer and the fabric. Prints and decoration only weigh down that concept.’

You’ve invented unprecedented clothes, like the ‘three-sleeve-hole’ jacket or the ‘free-leg’ dress. What role does the body play in your work?

Freeing up the body and allowing movement are both a major part of my work. You can wear the three- or four-sleeve-hole jacket with total freedom; it has no fastenings. Other pieces are about being wearable without ever constraining the body. Our skin itself is a source of inspiration to me. After one entirely white collection that concentrated on lightness, I created a ‘teenage acne’ dress with crêpe buttons, as well as a dress made up of seven layers of skin-like organza. The fabric of a dress is like the continuation of the skin – or a desirable version of it.

Your clothes seem to nurture a feeling of intimacy that feels non-negotiable and would be impossible for other fashion designers. You’ve designed a number of ballet costumes, notably for Trisha Brown, and in both your fashion and dance work, your design never breaks with this need for intimacy. Is that an ambition of your work?

If I had to give you a definition of haute couture today, I would talk about intimacy. Luxury doesn’t exist in things that are shared by everyone. Intimacy is the only real made-to-measure that exists; everything else is just ordinary. My shows favour spaces of closeness and a silent dialogue between those who are watching and those who are presenting their clothes. Models aren’t necessarily part of the shows; instead, each event is a space in which women of all ages and types can meet, just like in real life. A show is not about theatre; it deals with questions of women, of the self. That’s also true on stage for a ballet. My clothes are envelopes to accompany each person on her journey towards the self.

Epilogue

As I leave, Adeline André makes a sign at me from the bay window of her studio – a handkerchief waved on a balcony and the 21st century evaporates from view. After my visit to Passage Dantzig and its complex of artists’ studios from another time, I am reminded of why, since the beginning of my career, I have always thought of couturiers and designers as being as powerful and as ambitious as poets. Never mind the means, Adeline André will remain a figure in the history of fashion. Her fashion is literature. As I leave her in this humble setting of infinite prestige, it seems to me that sometimes it is others who make mistakes.