When photographer Mark Lebon transformed a garage in 1980s London into a creative playground called Crunch, he became the catalyst for a sprawling countercultural scene that continues to influence fashion today.

By Jerry Stafford and Carmen Hall

Photographs by Mark Lebon

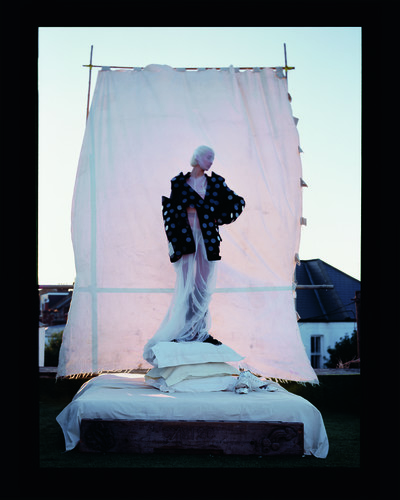

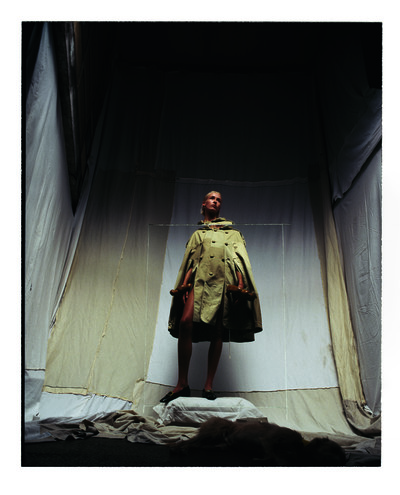

Styling by Amanda Harlech

When photographer Mark Lebon transformed a garage in 1980s London into a creative playground called Crunch, he became the catalyst for a sprawling countercultural scene that continues to influence fashion today.

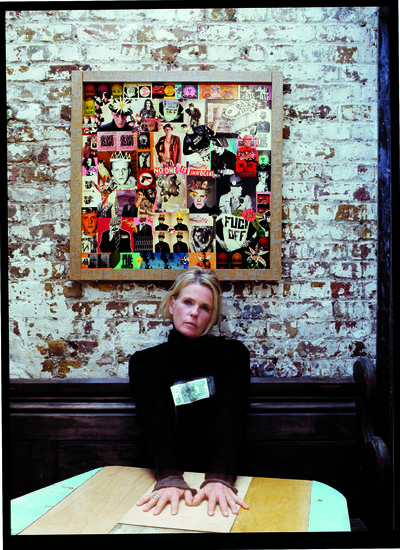

Stepping into Mark Lebon’s Crunch Studio on Wakeman Road in London is like entering a parallel universe. Chaotic, contradictory and sensorial, the precarious two-storey building is as much a sensibility as a space, the former-garage-cum-creative-playground a physical manifestation of its creator’s labyrinthine mind. Ringmaster, visual documenter, self-saboteur, contrarian and visionary guru: Mark Lebon has been a countercultural fashion iconoclast for four decades. His generosity, inclusivity and booming baritone have been legendary since his first images for i-D and The Face appeared in the early 1980s, while his enduring influence on both peers and protégés bears witness to an uncompromising creative approach whose core values of integrity and irreverence have remained constant.

Mark’s cross-generational group of collaborators and co-conspirators reads like a who’s who of London’s fashion and pop (sub)culture: Judy Blame, Christopher Nemeth, John Galliano, Edward Enninful, Jeny Howorth, Ray Petri, Simon Foxton, Neneh Cherry, Kim Jones, and Juergen Teller, among many others, as well as his sons, image-makers Tyrone and Frank. Kate Moss remembers hanging out at Crunch while still in school, and later living with Lebon and photographers Mario Sorrenti and Glen Luchford. ‘Somehow I already knew about Crunch,’ she recalls. ‘I was really attracted to that whole scene.’

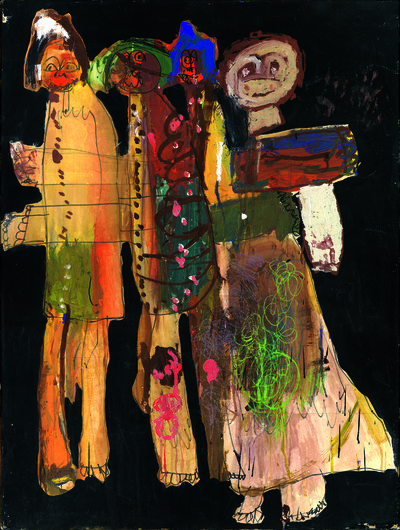

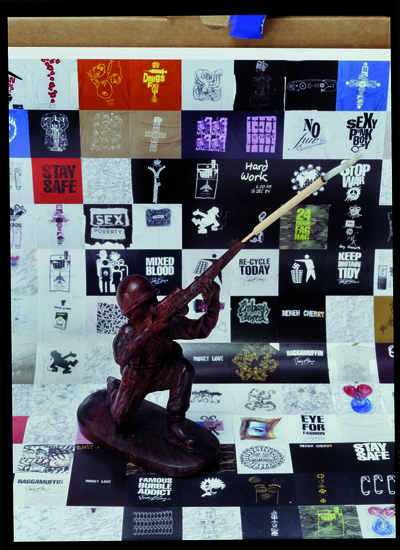

Within this collective space, Lebon has honed his craft through decades of industry feast and famine. Demonstrating an almost obsessive relationship to his signature visual tropes – cutting up and re-stitching negatives, double exposures, rephotographing prints, splicing and scratching Super 8 film – he has refined an aesthetic of deconstruction and reconstruction that he refers to as ‘the mash up’. It’s a technique and spirit that echoes the work of his closest collaborators, the late Nemeth and Blame, and laid a foundation for the likes of Martin Margiela.

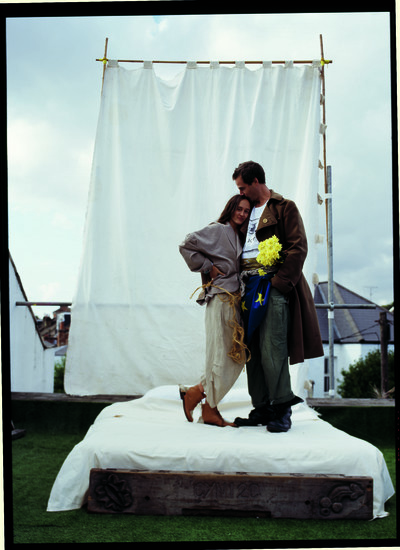

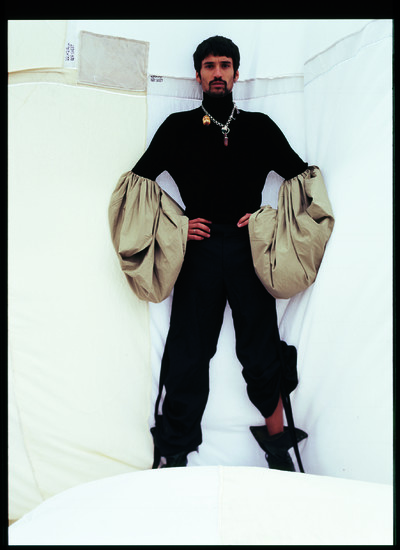

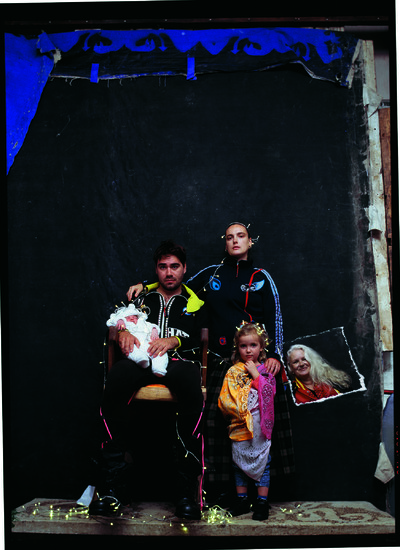

Mark recently approached System with the idea of creating a ‘final chapter’ for his ongoing archival project: a sprawling portfolio of new imagery, constructed around a recent collaboration with stylist Amanda Harlech. Shot at Crunch, those images are accompanied over the following pages by layers of photographic, artistic, written and archive fashion contributions by the extended Crunch family: from John Galliano’s 1984 graduation collection, Les Incroyables, to Judy Blame’s penny brooches, to Kim Jones’ latest Dior Men pieces. The result is a visual equivalent of Mark’s occasional dictum: ‘Small world, massive universe, infinite detail.’

‘I needed to deconstruct and

reconstruct my pictures for them

to be of any interest to me.’

Mark Lebon in conversation with

Jerry Stafford, 21 October 2020.

Jerry Stafford: Let’s go back in time. Where were you brought up?

Mark Lebon: West and Central London, and a little bit North. As an adolescent, I did quite a lot of East, and as a mature student, which I consider myself to be now, I’ve been taken South by my boys, because that’s… cool.

[Laughs] It is cool! What about your first visual memories ?

My first visual memory is looking over the cot at my younger brother on the Edgware Road in what I believe was a block of flats called Park West. I could only have been about two years old!

When did you first start getting interested in image, storytelling and music? For example, what was the first record you bought?

One record that springs to mind is ‘Leggo Skanga’. When I was 13, I started using a yoyo. It was one of the only toys that I ever got any good at. I was going to boarding school around Victoria Station and these West Indian kids were admiring my skills and they started shouting what sounded like, ‘Scanner! Scanner! Scanner!’ Then I heard the record ‘Leggo Skanga’ and I got into reggae.

Were you more into reggae and soul music as a kid?

Well, my mother used to play a very eclectic mix of music to me as I went to bed, but the first records I owned were Paul McCartney’s first album and Let It Bleed by the Rolling Stones. I didn’t actually buy those; I think they were probably bought for me. I was definitely Beatles rather than Rolling Stones. That’s cool or uncool, depending on what you think. I had breakfast with the Beatles when I was seven years old because my mother’s best friend was one of their secretaries. I remember being so embarrassed that I just sat on the stairs and I gave away all the autographs I got just to make friends at school. So, yes, I was sort of in the middle of it right from a young age!

When did you first decide that you wanted to work in the creative arts or photography? Did you go to college or art school?

I left boarding school because of a family breakdown situation and then I landed up living in my dad’s house. I ended up not taking my A-levels and taking loads of drugs instead. My style guru at the time was Toby Andersen, whose parents owned the Lacquer Chest, a very cool antiques shop in Kensington Church Street that I’ve been told influenced the Conrans and Habitat in the early 1960s. I was at art college in Worthing, a town where old people go to die. So there was a huge amount of second-hand clothes and we bought a lot of 1930s big, double-breasted suits. I did two years in Worthing. I repeated the foundation course as I couldn’t make up my mind on what I wanted to do. I then got invited to do a BA course in communications design that I wasn’t actually qualified for in the East End of London, which I rather liked; I did two years of that three-year course. At that time I was friends with Ray Petri whose degree of involvement in fashion back then was ironing his boyfriend’s clothes. Then he started dealing in antiques and became the agent of photographer Roger Charity. Through Ray doing that, I got connected into the fashion scene.

That was when you first decided to take pictures yourself?

I was quite socially engaged and politicized at the time, but was actually really disillusioned with the possibilities of social change. Windscale [nuclear power station] had opened and nuclear power had already become part of our national grid. I thought, ‘Fuck it, this ain’t going to work, I’m just going to enjoy myself.’ The idea of getting paid loads of money to take pictures of women was quite an appealing option. So I went for it. Ray and I ended up taking pictures of beautiful boys instead.

Can you remember your first job as an editorial or even a commercial photographer?

My first girlfriend Daisy was one of the first people I shot. Carlo Manzi did the styling; we shot her as a jazz musician in a men’s suit.

Was it for an editorial?

No, just as a test. My first editorials were for Girl About Town, an uncool free magazine; Miss London was the cool one. I always used to work for the uncool magazines. The Face was cool, i-D was uncool, so I worked for i-D. My first advertising job was for Laura Ashley [both laugh]. That’s when Camilla [Lowther] first started being an agent and I was on her first roster along with Perry Ogden.

You’ve spoken already about Ray Petri, but who were your initial collaborators in the fashion world?

Yvonne Gold, who was a great make-up artist at the time, was very important and ready to support me. There was also Carlo. We used to hang out at Bow Street. I was fortunate that Cameron [McVey] worked in a studio where there were about 15 different working photographers. So after having worked for him, I freelanced and worked for lots of different photographers. Then Ray slowly started to become a stylist and big news.

How did your relationship with Ray and the Buffalo family evolve? Did it happen organically?

No, it did not happen organically: I was coerced into Buffalo. It was quite a few years after I’d started, four or five years maybe, and I’d already had my son Tyrone, which was an odd thing to do at the age of 25, and it was all kicking off for me. I had started my own production company and I was two years down the line probably with Camila Lowther as my agent. I’d probably just met Chris [Nemeth] and Judy [Blame]. It was kicking off in a serious way for me with far too much going on. I got to take a picture for The Face; it was just one page of menswear: [model] Simon de Montford, with a torn-out picture on his chest. The credit for it ran: ‘Photo: Buffalo, Mark Lebon and Ray Petri.’ I was like, ‘What the fuck’s Buffalo?!’ This is my first credit with The Face and suddenly I haven’t got a fucking credit. I was really pissed off. Anyway, I was told that Buffalo was owned by Cameron [McVey], Jamie [Morgan] and Ray and it was an agency and there I was, part of this fucking agency without even being asked and that really pissed me off. Then Arena started and I got to shoot the first big stories for the first and second issues. All was forgiven, well, eventually forgiven, gradually forgiven.

What was your motivation in creating a space such as Crunch? When and how did you find its present home and create this sort of multidisciplinary collective workshop and playground?

I found this place about 10 years after having started Crunch. We had lots of different premises all over London before then. Basically, I think it was just my codependent sickness and deep shame about being upper middle-class and having stuff. So I wanted to help other people and that sort of went back into childhood trauma. I just escaped myself through supporting others, so it was really a sickness that drove me to try to support and help other people. Quite often I lose myself in helping other people rather than taking responsibility. Drugs weren’t enough! I needed to have a sickness with people to really knock any possible feelings on the head.

When I walk into the Crunch space now and see the Fric and Frack furniture and lights and Judy’s jewellery and collages and Dave Baby’s wood-and-stone-carved sculptural pieces, I remember how it was such a creative cultural hub…

I feel it’s all a bit of a myth – and that the myth became a reality. It was a bit of a myth because I never employed anyone; it was all sort of untrained people who came along, so it was never going to become manageable or a financial success. It was kind of a strange, weirdo, schooling thing that people got involved with. The first sense of it was at the New Cavendish Street flat where I was living after my mother died, when I met Judy and the Buffalo thing kicked off. That’s when I bought my first painting from John Maybury even though I actually went to college with John and knew him from that time.

He told me that he swapped a painting with you for a Christopher Nemeth jacket, which he still owns by the way.

Well, I’ve got very little of the painting left…

He told me it fell apart, but the jacket hasn’t!

I paid 200 hundred quid for that painting I’ll have you know! I’ve got it on the record. John’s jacket had one of Chris’s paintings constructed into the back.

Yes, it’s a beautiful jacket. How important has your relationship to fashion and designers been in your work and which ones have been the most inspirational in the London, Paris, Tokyo triangulation?

Obviously, Chris and Judy. I actually became their agent. Judy did his first styling with me. He just did accessories before then. So they were definitely a major part of it and were the biggest influence. Before them there was Ray and Toby Andersen, who I went to Worthing with, who was a very big influence as well. His band were called Funkapolitan and were into Antony Price. Antony’s was a silhouette that I really loved. I mean, he was the only one of that sort of big 1980s thing that I actually related to.

Who were the other designers that you then started exploring?

John came at sort of the same time as Chris and Judy.

John Galliano?

Yes. And then in Japan, it was a chap called Takeo Kikuchi. When he was working at his brand Men’s Bigi, he was the first person to take street-cast English fashion to Japan. Then that took off in Japan and all of the gang were around.

What about Martin Margiela? He was obviously someone you admired.

Margiela was sort of a little bit further down the line. We always felt that he had been influenced by Judy, and I had heard a rumour that when he saw the stories we were shooting in i-D, it encouraged him to leave Gaultier where he was working at the time to go and do his own thing. I’ve tried to get that story verified for this project, but still haven’t managed to do so!

That deconstruct-reconstruct ethos has always underpinned your own aesthetic, so Martin Margiela, John Galliano and the Japanese new wave designers like Rei Kawakubo were naturally close to your own process. Is this modus operandi something that you think has developed consciously or subconsciously in your work over the years?

Very, very consciously. Basically, I fucked up and I continue to fuck up with my photography. So I needed to deconstruct and reconstruct my pictures for them to be of any interest to me; not all of them but most of them need to be fucked about a bit for me to accept them. Because I couldn’t get it right the first time, being explicit about the process became my signature style. When you’re showing the process of something, you’re deconstructing it.

So it’s born out of your strong belief in and your adherence to an idea of risk and accident and making mistakes?

Yes, just incompetence probably as well! [Both laugh] Also, still having to come up with something that works, but not getting it right the first time. It was born through necessity, and then was further developed very consciously.

Why do you think your process is underscored by this self-destructive urge, this obsessive compulsion towards something that is unfinished or broken?

I think it might be because I have a certain degree of attention-deficit disorder; fear narrows my vision and I can’t see the bigger picture. I’ll fix it later, fuck it, just

move on, I’ll sort it out afterwards. Initially, we called the technique ‘mashing’.

I think that your whole process is just a reflection of life! I mean we do not live in a perfect world, particularly at the moment in the business of image-making. In fashion, there is an absolute and imperative need to take risks and to learn from our mistakes.

I suppose I’ve been very blessed in as far as I was given a lot of love as a child so maybe that’s given me the confidence to keep going in spite of shit happening.

I have learned to embrace the fact that I actually could work and I am lucky that I’ve had the confidence to keep going. Only a person who was given a lot of self-confidence can get away with that kind of behaviour. Having said that, I did have to take vast amounts of drugs.

You’ve got many admirers, whether photographers like Glen Luchford, Mario Sorrenti, David Sims, Juergen Teller, Cindy Palmano, or a whole generation of unique creative talent like Simon Foxton, Edward Enninful, Michael Kopelman, Stephanie Nash, Jeny Howorth. They all acknowledge the nurturing and attention you showed them at the start of their careers and afterwards. You’re definitely seen as a mentor or a father figure. How do you see yourself in that role?

It was obviously something I was up to because I actually had children of my own at quite a young age. As I said, it sort of came through an unhealthy need to escape myself, but I’ve done enough therapy to be aware of that and make my life manageable. I’m quite concerned that my sons haven’t learned from my mistakes because they have landed up getting involved with lots and lots of people and it can be very time consuming. It was an escape for me, but in the last 20 years or so, I’ve taken a slightly alternative route and stepped down from that. Then I ended up teaching and it made my role official. It gave me a break because I could make my sickness official. It became unmanageable however, because I didn’t teach in a way that the institution could handle.

Where did you teach?

At the London College of Fashion. I had 12 glorious years there and I was blessed to come into contact with a lot of great talent through my teaching – some really amazing photographers.

You’ve been talking about your relationship with your sons, Tyrone and Frank. How did you nurture their own creative dreams and aspirations?

I didn’t particularly; they were just in this environment that was all embracing. You know, it’s interesting that you draw parallels between my personal life and the sort of creative deconstruction and reconstruction because they are mirror images of each other. I never had any clear boundaries about what was work and what was play.It all became a bit mixed up, but when I started teaching, it gave me a discipline that made my life manageable. By the time I was in my late 30s, it was complete and utter chaos. I had to change things and I discovered that any amount of discipline was going to give me more freedom than not having any discipline at all. I used to think it was the opposite, but having boundaries gives one a sense of security and freedom – and that’s what teaching and being a single parent gave me.

This System project we’ve been working on for the past few months will ultimately become the final chapter of the first volume of your archive catalogue. Why the decision to make your work available to a wider public?

A lot of the work – at least half of it – happened in complete and utter chaos. About 20 years ago, my life started to become less chaotic and I began thinking that I needed to get my archive organized. I didn’t want to leave a mess for my boys. When I started teaching, they offered me money to process my archive because they wanted to pitch it to the Arts Council and the first strand that I showed was The Penny and the Postsack.

Can you explain what that is?

Judy’s the penny and Chris is the postsack, and the work I did with them remains the biggest part of my archive and a significant part of my creative career. Judy Blame is the penny because it was an old English penny that he made into a brooch and sold for a pound. I just thought, ‘Yeah! He’s selling pennies for a pound by putting a pin on the back! A 100% profit, I like it!’ Also, just the aesthetic: cheap, easy, quick. As for Chris Nemeth: he didn’t know how to make pockets and cuffs, so he’d just find old jackets and then mix them with his paintings and post sacks he found on the streets. I only recently discovered that the penny and the post sack were my own aesthetic, too: cheap, easy and quick!

‘We both had a vision,

albeit a solipsistic one.’

Mark Lebon and Amanda Harlech

in conversation, 26 October 2020.

Moderated by Carmen Hall.

It was a Monday morning when Amanda Harlech, Mark Lebon and I got on a Zoom call. Things began in a rather dull and predictably post-weekend mood. Mark had a backache; Amanda had a terrible toothache. She was in the countryside where her horse had lost a shoe and the farrier had arrived just moments before. Furthermore, delivery of the pictures Mark and Amanda had worked on together the previous month was two weeks behind schedule.

Having shot an entire roll of one of the looks – extravagant for Mark – only to find not a single photograph had both the model’s feet and face in focus, Mark had been distraught for days. But on the morning of this interview, Mark and Amanda came to realize that the shoot had come full circle.

Mark finally decided to run two separate pictures of the same Maison Margiela Artisanal look – designed by John Galliano – one with the model’s face in focus; the other with her feet in focus. Though repeating an outfit is something neither Amanda nor Mark like to do, they decided that in this instance it made perfect sense. Mark often listens to a recorded mantra from a body-awareness retreat. The recording repeats, ‘from the tip of your toes…’ which Mark placed on the photo featuring the feet in focus … and ‘to the top of your head’, which he added on to the one of her head in focus. It became an embodiment of Mark and Amanda’s spiritual approach to life: a perceived error turned into a key feature. A representation of the shoot’s celebratory approach to family, ‘realness’, and the passing of time, its exploratory deconstruction of fashion also happened in real life when a family dog idly peed on a piece of couture.

Carmen Hall: How did this shoot come about?

Mark Lebon: I bumped into Jerry [Stafford] in January and he asked me what I was up to. I’d spent a year working on making my Penny and the Postsack archives into a catalogue and I was interested in the last chapter being an exhibition and a magazine editorial. I was inspired by what Juergen [Teller] was up to; you know, he was the first of my contemporaries who worked in fashion photography and fine-art photography. Using fashion editorial to promote his art exhibitions. I wanted to do something like that, publish a book, create an art exhibit and use a fashion magazine to promote them. Jerry suggested working with System on the editorial part and asked me who I’d like to style it. Because I was interested in John Galliano being at Margiela, and because it has also been on my dream list to work with Amanda, I mentioned her. Jerry fixed us all up.

Amanda, when you were fixed up with Mark, what was your impression?

Amanda Harlech: Mark sent me a message describing this cycle of the past, the present and the future, and the last chapter of his book being like the ‘present future’. Resonances of Judy [Blame], Chris [Nemeth] and Mark’s engagement and their work – a deconstruction then a reconstruction – became the genesis for the shoot. There were a lot of conversations when I didn’t understand what I could bring. Initially, I thought I would be styling with John [Galliano], but because of Covid that just wasn’t going to happen. I was really interested in the idea, having not worked with John since 1997, but then it became about working with my daughter Tallulah, which was again exciting because she has a really fresh point of view. A light thrown on top of something that seems to be part of my very being, really.

Mark: One of my dreams in this project was to get together with John and make that link, and we have tentatively done that, because he was a huge part of your

family…

Amanda: He was really instrumental in this shoot, because he made sure I got what I wanted from the Maison Margiela Artisanal show, which is intrinsic to this whole legacy of Chris and Judy and Mark, because it was there tangibly in 2020/21. He was like, ‘Yay this is happening!’ And for me that was fantastic.

Mark: I am not someone to repeat outfits in fashion shoots, but we’ve got two fabulous pictures of that look, which in the end is all I really wanted from this, one or two pictures that sort of said it all, and they do.

Mark and Amanda, have you encountered one another regularly throughout the years?

Amanda: There were decades when we didn’t, but I do remember in the 1980s talking to Mark on a street corner and being mesmerised by what he was wearing.

Do you remember what he had on?

Amanda: Christopher Nemeth’s post sack jacket and trousers. That’s what I remember at least. At the same point I was working with John on Fallen Angels and there was just this, like a visual connection to that. We were all going in that direction. You can’t explain why, but it just seems like family, just to bring it back through the family tree to that.

Mark: The amazing thing is with something like Chris’s clothes, if you are into fashion, or John’s clothes, when you see them for the first time you feel so connected at such a deep level. This is someone that you relate to; it is visceral, right there on the surface, and such a profound statement.

Amanda: It’s like recognition and an embrace, it really is like that; it’s like coming home.

Mark: Whenever we did meet, there must have been that thing where on one hand it was incredibly superficial, but on the other hand, the superficial is deeply important as well. A strange duality.

What has the presence of family meant for you in this shoot, Mark?

Mark: Family has always been a priority for me because coming from what people regard as a dysfunctional family, it has always been part of my healing process to deconstruct that, and reconstruct a family. So with my kids it was, you know, I sort of deconstructed and reconstructed my childhood through being part of theirs. I deconstructed and reconstructed my growing-up process with them, too. It was lovely having our kids around on the shoot, too; there is that sense of family, a sensibility and just joy at having them around us. Amanda and I share that.

How does putting a fashion shoot together compare to constructing a family? In a way you’re building a support network and together you make it work.

Mark: Very much. My main partner in crime has been my stylist. I have been out of the ‘fashion family’ business as both my provocateurs, Chris and Judy, have not been part of my life for a while, so this one was about trying to sort out a new family. I think Amanda has been in a different family, too; her fashion family was Karl and other major characters. I had been a bit out of the loop in the old sense, in terms of a close relationship between a stylist and a photographer. I’d been bringing up Frank, teaching, and working on behind-the-scenes movies.

Amanda: We had to jump on this in two weeks! There is something quite innocent about it. And that could be a good thing.

Mark: A really odd selection of people ended up being in this cast, all collaborating. There were some extremely obscure connections and some people who are simply neighbours on my street, due to the current state of affairs, the circumstances that we found ourselves in. The whole appreciation of working with family has been stretched to its outer limits in this story. For me, Amanda has been the first spark of the dream family, because I would have always loved to work with Amanda and to create a sort of fashion-work situation. So that was the spark and as luck would have it, we have managed to hang out a bit together, too. It encouraged me to follow other really, really obscure avenues that I have wanted to resolve, a broader-based family and influences, and stuff like that.

Amanda, how has this project been for you, working with a new fashion family?

Amanda: The idea of family is really important. I wished I could have known everybody we were photographing a bit before actually dressing them, but then maybe not knowing them is a good thing, too. I had to sort of work out the connections between people and also, you know, the idea of who wears what was a spontaneous thing. Everybody was all together dressing themselves, which I think was right. So my experience of the family was intense! There was a process whereby the family was definitely a reconstructed family, a created family.

That sense of openness to improvisation feels related to one of the shoot’s central themes: ‘understanding the problems and living in the solutions.’

Amanda: You have to. If the clothes don’t fit then you have to make do! You can’t be controlling about the spinach, you see. That is where we started.

Mark: Maybe we should tell that story. In my first conversation with Amanda, I was telling her about how I had put my back out putting coffee grounds on some spinach, trying to stop the slugs from eating the spinach. Then we went rambling on into all kinds of discussion over the next half an hour and Amanda brought the conversation back to that central point – that trying to control the slugs was going to give me a really bad back in the end! That is what we have done with the story: we have let the slugs in and they have done a very fine edit for us. Working with someone on a level where they can interpret and understand your actual being, that is what happened with Judy and Chris and has just by some miracle happened again with Amanda. Letting mistakes in and celebrating what they have to offer, really.

Has ‘letting the slugs in’ been something you have practiced throughout your career, Amanda?

Amanda: I totally don’t like finished polished things; I don’t know why. I suppose that is like nature. Nothing is polished to a brilliance; there’s always one leaf that’s dying or one petal that’s changing colour, shrivelling. I don’t mean to be negative; I find a beauty in all of that. For me, it has always been about deconstructing things because that releases the spirit of the thing! If it is just an imposed perfection, somehow the heart of the matter escapes me. So, that is just me – an unfinished state!

If you let certain elements of a project take their course, how do you keep it feeling yours?

Amanda: It’s not about just sitting back and letting it happen. You have to allow space for change and change for the good. You can’t just lock it down. I remember the set broke in the wind and well, I actually didn’t mind because it made a really interesting shape. I remember saying, ‘You don’t actually always know what it is going to be, so when something happens you can roll with it.’ I can’t understand how to accept something as it is without deconstructing it and reconstructing it to make it mine.

So is ‘living in the solutions’ about letting go of control?

Mark: There’s this picture of my assistant holding his head in his hands in despair after we had spent two hours trying to mount the camera at a low angle on the floor. It was a moment that quite often happens to me when I am in a really important shoot that means a lot to me, when I just can’t control what is happening. So the lens that I had on the camera just wasn’t right and if I got too low it gave the wrong perspective. It was really getting painful and we had spent an hour and a half on it. Like, this is too painful, it can’t be right. So we lifted the camera and changed the angle to something I hadn’t wanted at all and consequently quite a lot of the shots didn’t turn out how I wanted. So in post-production I had to at least try and fix the pictures so they did some of the things I wanted them to do. It’s that thing of letting go of the control and of what you want, then actually just taking deep breaths and having faith that it will turn out all right.

Amanda: I mean, we both had a vision, albeit solipsistic ones, like, what Mark saw in his head and what I saw in my head. We were both working towards that because I believe that we are both acutely visionary people in that sense… without bigging ourselves up. So when you are working towards something, you know where you are going, which makes the voyage thrilling because you don’t always know what route you are going to take.

Mark: To me, there was a lot of pain involved in actually having to let go of a lot of the pictures that we did downstairs here, where I wasn’t getting what I wanted. I just had to let go and I had to think, it’s not the end of the world, I will sort something out, I need to embrace some of the mistakes. When I first looked at that shoot, I was deeply disappointed with my performance, particularly in the studio. But my boys said, ‘Hey Dad, this whole story is about understanding the problem and living with the solution. Get with the solution, Dad, that is what you are good at.’ And that put a smile on my face. I approached the pictures that I had a problem with, with a different mindset and as I said the spiritual element looked after us and the really key pictures look absolutely stunning. You know, it’s just having that faith to persist and to make the most of every moment that you have got. Not to wallow in the problem, but instead look for the solution. I think the story does now have that sense to it.

What was it like establishing a shared vision as collaborators, especially with a newly formed working relationship? How did you establish the themes of deconstruction, reconstruction, understanding the problems, living in the solution, joy, staying real and living in the dream and time?

Mark: Can I start off by saying that the themes of joy and time were Amanda’s contributions.

Amanda: To help me visualize how I could evoke a shoot for Mark to shoot, I brought in the poem ‘Burnt Norton’, from [T.S. Eliot’s] Four Quartets. Initially I just had to find a way in, and that was my way of doing it. We both said we didn’t want it to be a fashion shoot per se, that it was very much about the sense of wearing and that joy of the transformative dream. Which I think you can really see in some pictures, particularly in Dave Baby’s.

Why was now the right time for you both to do this? In a way, I guess it wasn’t.

Amanda: It is never the right time, but it is time. It is never the time to die, or to be born necessarily, so it is about embracing that and embracing the moment.

Speaking more to the future, how do you hope the subjects and the clothes featured in this story will make someone react? What do you hope the reader will think about?

Amanda: Take heart, dress, and investigate what you have already. Deconstruct and reconstruct it for you in this moment and it will always go on, you are not destroying something, it will live on. I really want people to be… inspired has too many capital letters about it, but it would be great if you could open it and look at these images and go, yeah, actually, I’ve got an old jacket I can turn inside out and wear in a different way. And in the process of doing that, it is a discovery about yourself.

And it is better for the earth!

Amanda: And that!

Mark: I would like people to react, again probably too many capital letters and exclamation marks, but… I’d like the first reaction to be, ‘what the fuck?’ But for them also to be stimulated and interested enough to find out ‘what the fuck’. You want to startle, but you also want people to have enough of a sense of identification that they want to investigate more, and feel it. To beboth shocked and surprised enough to want to investigate further means you actually become part of the process. My understanding of our art is that it is embodied in the object itself, the viewer, and the creator. There are the pictures, there’s Amanda and me and the rest of the team that has done the creating. Then there is actually your engagement with what is going on! And if you manage to spark those elements, that is what good artistry is about.