When Kim Jones asked painter Peter Doig to collaborate on this season’s Dior Men collection, the uncanny ties between the artist and Christian Dior himself slowly began to reveal themselves…

Interview by Jerry Stafford

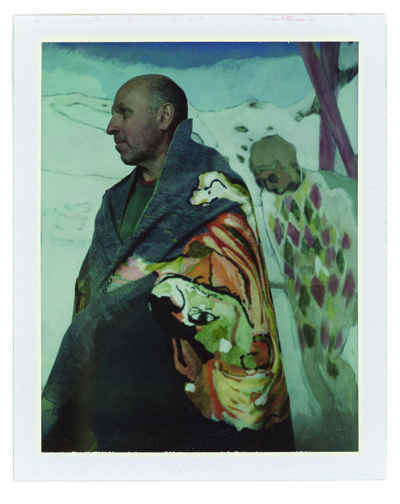

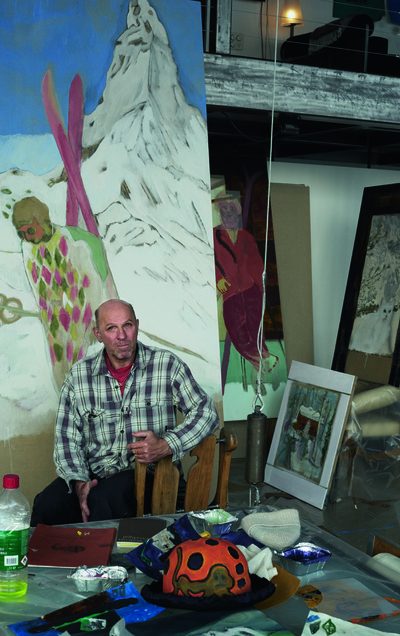

Photographs by Benoît Peverelli

When Kim Jones asked painter Peter Doig to collaborate on this season’s Dior Men collection, the uncanny ties between the artist and Christian Dior himself slowly began to reveal themselves…

British artist Peter Doig can spend up to three years completing a single canvas, without either personal or studio assistance, leading an almost hermetic existence in the tropical highlands of Trinidad, where he has lived and painted for many years. As creative director and designer for Dior Homme and Fendi, Kim Jones currently produces a dazzling display of eight commercial collections a year and works with an extensive design team that straddles Paris, London and Rome.

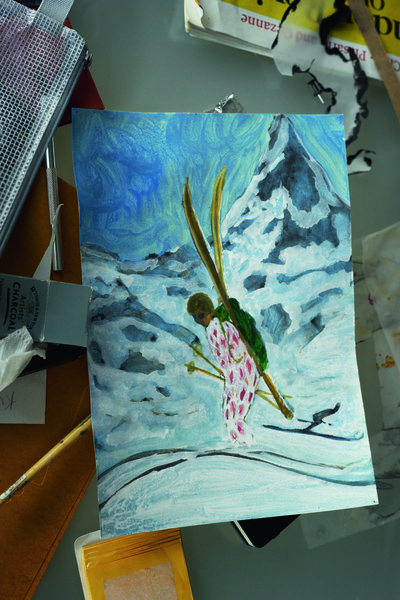

Doig is a resolutely private individual who habitually shuns the spotlight even though he is one of the most celebrated artists of his generation, while Jones’ meteoric rise to fashion notoriety has catapulted him to the centre of an international media circus. Doig, an avid skier and winter sportsman whose work has often been inspired by his passion, spends several months of the year in the tiny Swiss mountain resort of Zermatt, exploring its precipitous peaks and slopes. Jones, meanwhile, is more at home on the vast sun-baked plains of Africa.

Although their work and their worlds might not at first glance seem mutually compatible or coherent, Jones approached Doig over the summer of last year to collaborate on his Autumn/Winter 2021 Dior Men collection. The designer is the first to admit that, ‘everyone was a bit shocked when I said we were going to work with Peter. People knew and loved his work, but he is a bit of an enigma. I wanted to turn things up a bit, in a different way.’

After a tentative text correspondence, the two finally met at Doig’s home in London, where the walls are hung with work by painters for whom they discovered a mutual admiration. A creative and personal rapport was quickly established that revealed common ground in both their past and present lives. Both graduates of London’s Saint Martins – Doig in fine arts, Jones in fashion – they also share a love of the moment in the early 1980s when the school was the epicentre of a now legendary art, club and fashion scene filled with larger-than-life creative characters – among them Judy Blame, Boy George, Leigh Bowery and John Galliano – who spent their nights at underground clubs such as Blitz and Taboo. Doig experienced this highly influential world first-hand as a student, while Jones has been almost obsessively fascinated by it since the start of his career in the early 2000s. ‘It’s very rare when you meet people who have the specific references that Peter and I share,’ says Jones. ‘It just blew my mind, the music he was playing and the artists he was talking about, like the painter Trojan and the whole world of Leigh Bowery. They have all always fascinated me even though I didn’t see them myself.’

An unexpected and fascinating creative synergy emerged from these initial meetings, and Doig and Jones then spent time looking into Dior’s extensive archive, where uncanny correspondences between the artist and Christian Dior became apparent: a painting by French illustrator Christian Bérard once in Christian Dior’s own collection is now owned by Doig, and a photograph of Dior dressed in a lion costume, which Doig reinterpreted for the show’s invitation, reminded the painter of his own signature Lion of Judah motif. ‘I always look for things that bring us back to Dior as a French brand, and so to where there was a relationship between Dior and Peter’s work,’ says Jones. ‘So we looked at some of the ceremonial aspects of his work, which are also found in Le Douanier Rousseau, who we both love, and we then pulled it back to Paris.’

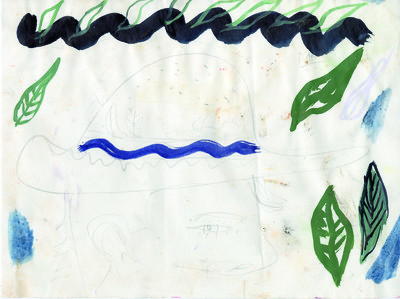

Together, Doig and Jones explored the rich visual lexicon of the artist’s body of work for inspiration – the hypnotic, often hallucinatory tropical and mountain dreamscapes, and elusive enigmatic figures – and Doig created new material specifically for the menswear collection, working closely with Jones and his design team on every aspect and detail. Milliner Stephen Jones, a close friend of both designer and artist, who has worked with Dior for over 20 years, even travelled to Venice, where Doig was in lockdown last Christmas, to collaborate on the exquisite hand-painted bowlers and berets that would feature in the presentation. The elements of Doig’s work selected for the collection were then gracefully and meticulously transferred from canvas to clothing thanks to Dior’s couture atelier, which skilfully translated the sensorial and layered nuance of his painting technique into embroideries, jacquards, knitwear and prints.

The result is arguably the most accomplished artistic collaboration of Kim Jones’ career at Dior and can be seen as a benchmark of how to approach and make a success of what may now be a fashion commonplace, but too often feels gratuitous and unfulfilling. ‘Peter works in a very solitary way, while we work as a team in a collaborative way,’ say Jones. ‘But I think he really enjoyed being part of our community, especially in light of the recent restrictions. The whole creative process was exciting. Everyone really respected him as an artist – and I made a great new friend.’

Jerry Stafford: The photographs that Benoît Peverelli shot with you around Zermatt for this feature are epic.

Peter Doig: You could tell he was genuinely blown away. He’s Swiss and he was shocked that he’d never been here before – it was the first time Benoît had seen the Matterhorn.

He couldn’t take his eyes off the mountains. He told me he saw more wonder in that one day than he’s seen in the previous three months.

It is the supermodel of peaks!

You got to the ice cave, too.

Benoît seemed to be pretty adventurous. Getting in there was OK – getting out was a bit trickier.

Let’s discuss your Dior Men collaboration with Kim Jones. How did it come about, and how did it evolve?

I didn’t know much about Kim’s work, other than that the Chapman brothers, Jake and Dinos, had worked with him. I started just talking to him and getting to know his interests. I was intrigued by the art that Kim has collected and is passionate about. It felt surprising, considering how his work is so associated with pop culture, people like Supreme. Then to find out that he was really into the Bloomsbury Group and how that was connected to where he comes from, I found that surprising. I liked that he really appreciated work that was to do with touch, and that he was passionate about painting.

So you met up in London?

Kim texted me a few times, but I first met him when you both came round to my place. You instigated those initial meetings and that was when I realized that there was a lot of common ground and shared interests. Kim seemed to be willing to allow the collaboration to be its own thing, rather than something prescribed. He didn’t just want four or five of my images to turn into something; he seemed to be intrigued by my interest in being more involved than that.

What were your initial feelings? Were you slightly distrustful of this kind of relationship? It’s become something of a trend in the fashion and art worlds.

I did look at the downside to begin with. Why commercialize the work to this extent? Is it necessary? No. So, why do it? What’s the point? But then I thought maybe that was an interesting thing. In some ways, it is not much different to working with a really great print studio when you make a limited edition; there is very much a craft element when you make the etching plate. You might create an edition of 30 or 200, but that is mass-producing your own work, whether you like it or not. I spoke at length with Stephen Jones and he talked about the Dior atelier and the couture aspect of the collection, which sounded really exciting. Even though some items would be mass-produced, there was an opportunity to engage the atelier and make garments that would utilize the level of skill and craftsmanship there, which is second to none. The idea of working with this old studio was exciting, one with this tradition going back to when Christian Dior himself was alive and working. Then, of course, remembering that Dior had also been an art dealer, before he was a fashion designer and had relationships with many artists was exciting. In fact, I own a painting by Christian Bérard that once belonged to Christian Dior. His work is very painterly, very expressive; it’s open.

How was that first meeting at your place in London? It’s a wonderful space hung with many paintings, some of your own but mostly other artists you admire…

There was some work there that Kim also collects, like Trojan, so there was that connection. That led him to talk a lot about the work of those designers from our generation, from the early 1980s, who he really respects and collects: Leigh Bowery, Rachel Auburn, Christopher Nemeth, Stephen Linard. He has his own archive and it was really interesting to see he had gone to such lengths to collect. It’s not just a piece here and there; it’s really obsessive.

Your work with Michael Clark also really excited him…

The Michael Clark exhibition was just about to open at the Barbican and he was lending a painting and other works. A painting I had made for one of Michael’s performances was also in the exhibition, so there was that connection as well. He was obviously also very interested in dance music, with quite a collection, including a lot of Larry Levan stuff. And I remember even at the first meeting in the house, he was already talking about potential music for the show; it was the whole package rather than just a few sketches here and there. That got me quite excited, because it felt like we were embarking on a stage production, something theatrical, an entire event rather than just a few sweaters.

‘I’m an artist who works on his own – I’ve never had an assistant – so to be invited to work with this group of people was something I really enjoyed.’

That club culture we personally experienced as friends, from the late 1970s to the late 1980s produced a lot of artists, some of them well known, like Cerith Wyn Evans or Isaac Julien, others less so. Both you and Kim have always been great champions of those lesser-known artists, like Trojan, Duggie Fields or Caroline Coon. What do you think was so special about that time?

Without getting too nostalgic, it was fascinating because we all seemed to have so much time on our hands! That was partly because there were very few career possibilities for most of us, so we used our time, and we had the gift of the dole and very cheap housing! This is all stuff that has been talked about so much, but it is really important. Itastounds me that an artist like Trojan, who died at the age of 22, was such an active person and produced so much work during his daylight hours, or his night-time hours. I don’t know how he did it. It just seems to keep on, things keep on appearing, and you think, how did this young person do this? But he wasn’t the only one. People found the time to do things. There were so fewer distractions; we didn’t have computers or phones. We just had this camaraderie and places where you met in the evenings or at night and then you had these vast days to just sort of fill. And I think a lot of people made great use of that.

What do you think Kim takes from that period?

All the stuff that he loves and that we all appreciate was made by hook or by crook, on a shoestring and yet, that itself is like the height of couture, the height of handmade craft and self-expression. All those things are very difficult to do when you work for a big fashion house.

One of your first shows was in Florence in the mid-1980s alongside Trojan, artist filmmaker John Maybury and photographer Holly Warburton. How did that show come about?

It was the first foreign show and came about via two people, Victoria Fernandez and Iain R. Webb. They had been asked to do some sort of fashion exchange with a shop in Florence called Luisa Via Roma, which had this art side, too. The shop was closed because it was August and totally empty, so they took the opportunity to turn it into a gallery. The interesting thing is that in those days, no galleries in London would take on the likes of those artists or give them a break. It was a strange

time because there was so much happening for designers and so much possibility and visibility through the press with new magazines, like i-D, The Face and Blitz, but for young artists, there was very little or no exposure. Back then, exposure meant seeing something in real life or pictured in the press. There was nothing in-between, unless someone sent you a photograph they had taken of the thing and sent it to you in the post. It was a very different time.

You and Kim both attended Saint Martins, but at different times. Were your experiences there similar in any way? Who were some of your contemporaries?

In my time, there was a huge amount of social crossover between the fashion department and the painting department. We socialized within the college because we had this great café run by Coffee Bar Dave where people would meet sporadically during the day. That would then spill over into the pubs and the clubs at night. John Galliano was a contemporary of mine and best friends with one of my best friends, the painter David Harrison. So John was often in the painting studios and

David’s space was always like a little social quarter. He would be working, painting and chatting with his gang sitting around and they would often feature in the paintings. It was quite something. I couldn’t work like that! It would be fair to say that he was a real mentor to John and to Isaac Julien. A little older than me, a year ahead were Fiona Dealey, Richard Ostell, Darla Jane Gilroy, and of course, Stephen Linard. Cerith Wyn Evans had been there the year before, as had Stephen Jones, but their presence was still very much felt. We would see them around. At the time, the scene around Saint Martins was vast. There would be people like

George O’Dowd coming to the college parties, which were very popular. There were the pubs we went to on Thursday and Friday nights, where students from other colleges would come and other interesting people, before we went to the clubs. Saint Martins was a kind of a hub.

‘Kim allowed the collaboration to be its own thing, rather than something prescribed. He didn’t just want five of my images to turn into a few sweaters.’

As you said earlier, Christian Dior himself had a long and important association with artists and early 20th-century figurative art. Did this influence how you and Kim approached your preparatory work?

We definitely discussed it and it was exhilarating to remember that Dior had owned this painting by Bérard, for example. I was reminded of it when I was in the archives in Paris, flicking through books and there was this picture we found of Dior in his study with the painting behind him – that sent a chill down my spine. I also looked into other artists who had worked with in or dipped their toe into fashion and there was Zika Ascher, who made textile prints in London with Henry Moore and also for Dior. There are unexpected people, too; look, for example, at the decorative work that Francis Bacon did before he became a painter. So I just

thought, if you are going to do it, do it on your own terms – and I think that is what we did. We worked in a way that was maybe unusual for Kim, but I think he and his design team enjoyed it.

During your visits to the Dior archive you discovered a photograph of Christian Dior dressed by Pierre Cardin in a lion costume. That must have been a bit of a eureka moment.

The archive is basically run by one woman, Soizic Pfaff, who has been working at Dior for decades and decades and knows the archive inside out. We could just ask her if she had anything on for example Dior and Bérard’s relationship, and she would bring out books, pictures and files. We also looked at a lot of shoes and clothes and hats. The hats were really impressive – they were so handmade and witty, and beautifully crafted. So, one day, she pulled out this photograph of Dior

wearing a lion costume, which as you say was designed by Pierre Cardin, who had made the costumes for Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast that Bérard had designed. I had already begun bringing some of my lion imagery and colours from those paintings into the collection, but I was a bit nervous because I think of the lion as being sacred in a way. The Lion of Judah is probably one of the most mass-produced of religious images after Christ, but I was still unsure about mass producing it, about whether it was the right thing to do. Seeing Dior in the lion costume at a ball in this really carnival-esque image made a really strong connection, because I’d made a painting of a carnival lion that we had decided to use in little bits of the collection. I ended up putting it on the invitation and on the ‘Leigh Bowery’ hat that you brought to Zermatt for the shoot.

How did you get so involved in the collection’s creative process when we were all pretty much locked down because of the pandemic?

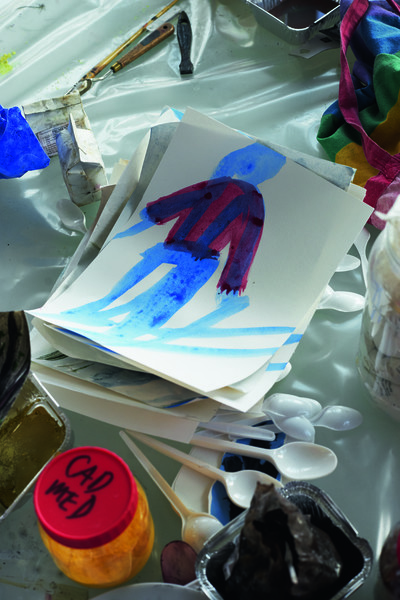

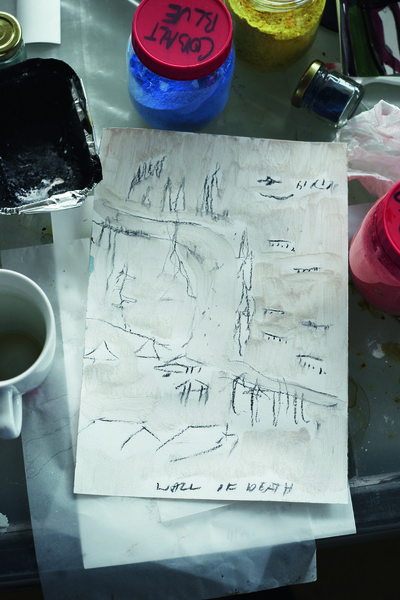

Like I said, I was very excited by the idea of working with the atelier. There is one in London and I naively thought that there would be people beavering away making things and I would be able to just pop in once in a while and see someone doing some embroidery. It didn’t quite work out like that, but I did go to all the design meetings. They reminded me of a tutorial: a group of people sit and look at the artists’ work and then make comments. It was fascinating. When we decided to go forward with the collaboration, I went through all my paintings and took details of all the clothes and costumes that I have painted over the years, the ones I thought were relevant and then I sent those to Kim en masse. I put them into different categories and then I went through paintings and chose things that I thought might make interesting patterns. There was a whole skiwear idea, so I went through the ski-related works. I probably overwhelmed him with imagery. I was astonished by the speed at which things happen in this fashion world; I was not prepared for that at all. At first, I primarily resorted to things that I had already made, but as the collection evolved, I made quite a lot of new work specifically for it.

Did you explore the work together with Kim and consciously choose to accompany those existing characters or motifs from the canvas to the clothes?

We went through a period of a good few months where I was constantly sending him images by text – probably bothering him immensely – and he would respond. If he didn’t, then I guessed he probably wasn’t interested, so I would send him something else and get a response, and there was this back and forth. He had already started looking at the silhouettes and the make up of my painting Gasthof zur Muldentalsperre in which there are these two figures, one wearing a Napoleonic soldier’s costume and the other a long smock coat like the coats worn by the Beaux-Arts students, the long bright-coloured ones with the gold trim on the inside. Kim had already started sending me mock-ups using old theatrical costumes, cut up, and the beginnings of ideas using existing clothes that they had found or just adapted. It was very much like going back to the early 1980s when people found things at Laurence Corner or theatrical shops and then adapted them. He had a starting point and then I was sort of adding to it, I guess. I was surprised at the first meeting how evolved it already was and how much had been done over the course of a couple of months, all that Alex Foxton, the head of tailoring, Edward Crutchley, director of fabrics and graphics, Janosch Mallwitz, the head of leatherware, Brian Moore, the knitwear developer, and footwear designer Thibault Denis had come up with in such a short time.

‘Christian Dior had also been an art dealer before he was a fashion designer. In fact, I own a painting by Christian Bérard that once belonged to Dior.’

How did you and the teams approach translating your canvases to the clothes? What was the process? You obviously really enjoyed it.

I did enjoy it and I also realized just how hit and miss it is. There were so many experiments and trials that we cast aside. You start to realize what works in certain mediums and what doesn’t. You can turn almost anything into some photographic reproduction technique, but we wanted to use traditional silk screening in some cases and jacquards in others, but I found that if you try to reproduce a painting in embroidery, it loses something. It’s not the painting and it’s not an embroidery; it’s somewhere in between the two. The lion blanket was the one we decided to go all out on and they did an amazing job with that, but there were other things

that ended up looking a bit like Grandma Moses’ version of my paintings, even though they already look a bit Grandma Moses sometimes!

Was there anything that you flatly refused to do?

Some of the translations of the work bled into the comical. You have to be quite strict with yourself and that’s why when we did use imagery, we tried to interpret the paintings in a subtle restrained way. For instance, for the print of Gasthof zur Muldentalsperre, it became pure silhouettes, like a smoky silhouette, a ghost image, instead of going into all the detail. The details were in the clothes themselves, as well as the buttons, the insignia, the passementerie. One of Kim’s first collections used that same military reference, so I think that was something in his past and mine, and that’s maybe one of the reasons he was excited by it.

Was it satisfying working with Stephen Jones, who you knew back in the 1980s at Saint Martins? How did you experience this renewed friendship?

Stephen was always there; he was at all these meetings. He has been around a while and his opinions are very much respected. He has great knowledge of the archives and the history of Dior, so he is an incredible resource. He is also a brave and inventive designer, almost a sculptor really, and always encouraging and open. If it hadn’t been for him I would have been very nervous about putting brush to felt, but he was so enthusiastic about the idea and it felt like the experiment that it was. One of the first things I did when he suggested making these hand-painted hats was to Google ‘hand-painted hats’ and the results are the most hideous things you have ever seen in your life! So it was a challenge, and then for someone to put it on their head… Then I started to get more in tune with the idea of the show being an event, a masquerade, and the hats became maybe more playful than some of the other stuff we did.

It’s interesting you use the term ‘masquerade’, because I know Stephen came to see you in Venice over Christmas. Is that where the idea evolved or had you spoken about it before hand?

Stephen had already given me strips of felt and rabbit fur, and I had started experimenting with colour on them, just doing dots of colour. I found that using good quality powder pigment bound with rabbit glue – which is actually made from the skin of a rabbit and was a pre-Renaissance binding mechanism painters used to bind the pigment and place it on the canvas or wood – worked really well on the felt, because it is basically coming from the same animal. Then I had to come up with images for the hats. I didn’t want them to be purely painterly, but certain things were interesting. Like the black was so black that for a lot of the hats, I left the

black as a kind of a void. Stephen sent me the ‘blanks’, which was this special bowler he had designed. It reminded me of those hats from the early 1980s, like

Buffalo, like the Witches collection by McLaren and Westwood; it certainly wasn’t like a businessman’s bowler. It had this very interesting rim that looked as though it had been bent or chewed. As I got into painting them, I felt more liberated, enough to paint the brim and to actually slap the paint on and allow it to be caught by the shape of the hat. Stephen was incredibly enthusiastic about it and he came to Venice to collect the hats, which was special because this was during lockdown and Venice was pretty much empty; it was just a special time. I’m an artist who always works on his own – I’ve never had an assistant or anyone else in my studio – so to be invited to work with this group of people during lockdown especially was somethingI really enjoyed. I haven’t found it easy to work during lockdown; I haven’t relished all this lockdown-ness. I probably haven’t been the most productive in my own work, so it felt like the right time to do something with someone else.

‘It was like going back to the early 1980s when people found things at Laurence Corner [army-surplus store] or theatrical shops and adapted them.’

Moving on to the initial ‘skiwear’ influence you wanted to bring to the collection and the relationship with the town of Zermatt in Switzerland. How did you initially propose working with the team on those elements in the collection?

I thought – naively, I guess – that winterwear could naturally incorporate skiwear and winter jackets like the puffer-type or ski jacket. So I got excited by that idea and made quite a lot of work especially for that part. Then when I went to the first design meeting it became clear to me that I had kind of veered off at a tangent! Then I found out about Dior’s ‘ski capsule’ collection, and Kim and the team asked whether they could use the ski ideas for that! It’s almost like a separate collection.

Are you particularly interested in the style associated with skiing and mountaineering? It’s often a theme in your work. I know that you’ve been particularly inspired by some of the archival films from the 1940s that Heinz Julen screens in his Zermatt restaurant. These clothes have a really strong style.

I’m really interested in the history of skiing and the development of equipment. I have a particular passion for skiwear from the 1970s, my teenage years. I understood that we couldn’t do something totally nostalgic, but there are definite references to particular brands and styles from that time in this capsule collection. I hope we are making a toque, a hat that was influenced by a climber’s hat worn by Heinz’s father, August, in one film.

Are you developing the new capsule collection from Zermatt, where you have also set up a painting studio and are preparing a show?

There are references to Zermatt in the paintings going into this collection. The Matterhorn does feature on a few of the garments and is something I am constantly thinking about. We’re almost there now; it’s being finalized. We’re pretty close; it’s not as big as the main collection. It’s a small, concise collection, but something I’m particularly interested in as I’m an avid skier. I had my own personal preferences in mind when considering what was being made, thinking about the technical aspects of the garments and their functionality.

Tell me a bit more about Zermatt. Why does it have a particular magic for you as a place for both skiing and as a place to work?

Meeting Heinz Julen was very important for me. He is very much a man of Zermatt; his family is one of the oldest families there, and they are deeply entrenched in the community. He is also a self-taught artist and architect working in this landscape; it was really inspiring to meet someone like him. My children have become good friends with many of his relations, so it made our time in Zermatt particularly special. It was always my fantasy to be able to work in the mountains and ski. Skiing has been one of my great passions since I was a child. If I hadn’t become an artist, I’d have wanted to become a ski bum. Then there’s the setting: the Matterhorn has this incredible presence, unlike any peak in the world. It’s just majestic. You never ever get tired of looking at it and it changes constantly. It’s so far beyond the cliché when you are in its presence.

Zermatt represents such a contrast from your life and work in Trinidad, with its music, carnival, people and poetry. Did you also want to explore that particular culture in this collection? I’m particularly thinking about that marriage between your work and the poetry of Derek Walcott, the St Lucian poet, with whom you collaborated on the book Morning, Paramin that featured Alpine and tropical landscapes.

Even though it is a winter collection, there are a good number of references to my work that are very much out of Trinidad. Derek liberated those thoughts for me because in that book he talked about Switzerland and he talked about this switch where he imagined parts of Trinidad in the snow and almost like a Swiss village. He had really experienced both worlds or many worlds. He was able to reflect on those thoughts and those notions even when he was back in what was his own world, the Caribbean; he could bring these layers of experience and imagery.

‘You can turn almost anything into a photographic reproduction technique, but we wanted to use traditional silk screening and jacquards.’

You’ve long been involved with the local community in Trinidad, particularly Port of Spain. You’ve mentioned the idea of setting up a bursary or artistic scholarship with some of the money from this collaboration with Kim.

I’m going to put all the money into it. I want to set up a foundation that will allow young Trinidadian artists and designers to go and study abroad as part of an exchange. This partly comes from my own experiences of the 13 years I spent teaching in Düsseldorf: there were three students from Trinidad, who had all found it difficult to find the means to get there. They managed to duck and dive to do it, but it was really tough for them. The concept of studying abroad for many kids is just not an option really, unless they get what is called an ‘island scholarship’ and they are generally not given to kids working in the arts. So my idea is to set up a foundation or a bursary fund for students looking to study fine arts, fashion, film abroad. Beyond that, I am just really interested in exchange; Chris Ofili, Lisa Brice and I all ended up in Trinidad on an exchange programme that sadly no longer exists. It was vital for us and many others.

Just swinging back, I wanted to talk about the show’s set design and your relationship to its conception and execution, as well as the fact that it wasn’t a live experience. We were talking before about the theatricality of the show and how that was very exciting for you, so how did you experience that transition from a live to a digital experience?

I got very excited at the idea of a ‘presentation’. Kim came to my house and he saw these old 1950s cinema speakers I have and said maybe we could use these on the stage for the show? So I started doing sketches and drawings incorporating the speakers, imagining them in a landscape. In Trinidad, it is not uncommon to see huge speakers set up in a field next to a bar, for instance. So I started making drawings or thinking about collages, of stacks of speakers in a landscape. We used Milky Way, a painting of mine that was referred to a lot in the collection, as a backdrop. Often you’ll see guys standing on speakers wearing certain clothes and striking a pose. So I had this idea that the catwalk could be on different levels; people could be standing on speakers; people could be walking in front of them, and it evolved from that. We started off with these two big European speakers in the centre as a sort of homage to music that we loved – we played Kraftwerk through them for the presentation.

And of course, these speakers were originally owned by Florian Schneider of Kraftwerk.

The original ones were, but for the stage show, we blew them up to more than twice their actual size. I gave the designers who produced the show, Villa Eugénie, images of speakers from my own paintings, so it became this amalgam of my real life and painted world. I was very nervous about seeing the stage set in real life because I had this horrible fear that it would be one of those Spinal Tap moments when you would go in and the scale would be completely wrong, but actually they got it absolutely right. It was better than what I had imagined; they did an extraordinary job. The only sad thing is there was no live audience, but with the ongoing pandemic, that couldn’t be avoided, alas.

What have you taken away from this experience and this collaboration? You talked about working with a close-knit team and also the fast pace of fashion and in particular collaborating with Kim and his team. Is this something that has made you approach your own work in a different way, or has it just been a wonderful parenthesis in that deep-time mode in which you work?

In the end, the way that I work, that is to make paintings, remains unchanged. It’s a slow and solitary process, but what I can say is that I got a lot out of this collaboration with Kim and his team at Dior. As an artist, if you work in another medium or context, if you do it right, it should feel that it’s somehow part of your body of work, not something that’s an aside. It should be something that you can feel proud of and stand behind and that’s how I feel when I reflect upon this collection.